'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label mob. Show all posts

Showing posts with label mob. Show all posts

Monday, 6 December 2021

Saturday, 30 January 2021

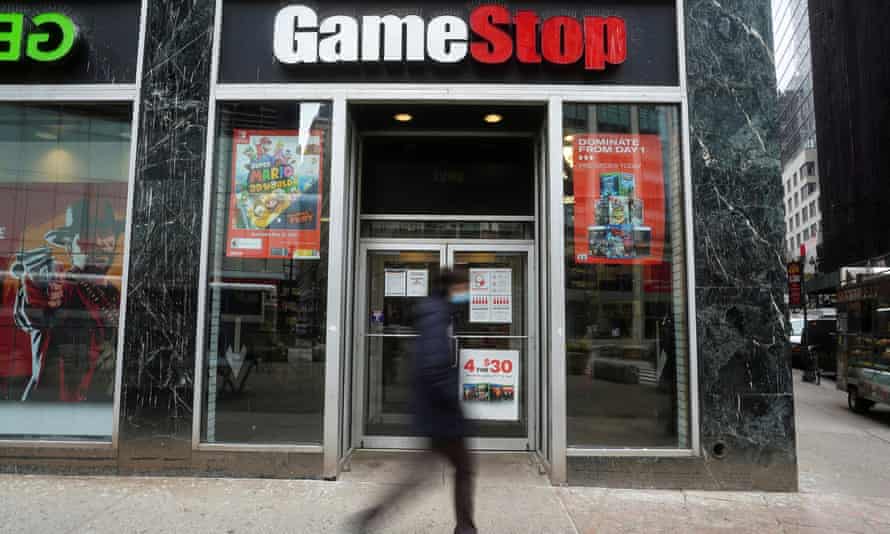

The GameStop affair is like tulip mania on steroids

It’s eerily similar to the 17th-century Dutch bubble, but with the self-organising potential of the internet added to the mix writes Dan Davies in The Guardian

Towards the end of 1636, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in the Netherlands. The concept of a lockdown was not really established at the time, but merchant trade slowed to a trickle. Idle young men in the town of Haarlem gathered in taverns, and looked for amusement in one of the few commodities still trading – contracts for the delivery of flower bulbs the following spring. What ensued is often regarded as the first financial bubble in recorded history – the “tulip mania”.

Nearly 400 years later, something similar has happened in the US stock market. This week, the share price of a company called GameStop – an unexceptional retailer that appears to have been surprised and confused by the whole episode – became the battleground between some of the biggest names in finance and a few hundred bored (mostly) bros exchanging messages on the WallStreetBets forum, part of the sprawling discussion site Reddit.

The rubble is still bouncing in this particular episode, but the broad shape of what’s happened is not unfamiliar. Reasoning that a business model based on selling video game DVDs through shopping malls might not have very bright prospects, several of New York’s finest hedge funds bet against GameStop’s share price. The Reddit crowd appears to have decided that this was unfair and that they should fight back on behalf of gamers. They took the opposite side of the trade and pushed the price up, using derivatives and brokerage credit in surprisingly sophisticated ways to maximise their firepower.

To everyone’s surprise, the crowd won; the hedge funds’ risk management processes kicked in, and they were forced to buy back their negative positions, pushing the price even higher. But the stock exchanges have always frowned on this sort of concerted action, and on the use of leverage to manipulate the market. The sheer volume of orders had also grown well beyond the capacity of the small, fee-free brokerages favoured by the WallStreetBets crowd. Credit lines were pulled, accounts were frozen and the retail crowd were forced to sell; yesterday the price gave back a large proportion of its gains.

To people who know a lot about stock exchange regulation and securities settlement, this outcome was quite inevitable – it’s part of the reason why things like this don’t happen every day. To a lot of American Redditors, though, it was a surprising introduction to the complexity of financial markets, taking place in circumstances almost perfectly designed to convince them that the system is rigged for the benefit of big money.

Corners, bear raids and squeezes, in the industry jargon, have been around for as long as stock markets – in fact, as British hedge fund legend Paul Marshall points out in his book Ten and a Half Lessons From Experience something very similar happened last year at the start of the coronavirus lockdown, centred on a suddenly unemployed sports bookmaker called Dave Portnoy. But the GameStop affair exhibits some surprising new features.

Most importantly, it was a largely self-organising phenomenon. For most of stock market history, orchestrating a pool of people to manipulate markets has been something only the most skilful could achieve. Some of the finest buildings in New York were erected on the proceeds of this rare talent, before it was made illegal. The idea that such a pool could coalesce so quickly and without any obvious sign of a single controlling mind is brand new and ought to worry us a bit.

And although some of the claims made by contributors to WallStreetBets that they represent the masses aren’t very convincing – although small by hedge fund standards, many of them appear to have five-figure sums to invest – it’s unfamiliar to say the least to see a pool motivated by rage or other emotions as opposed to the straightforward desire to make money. Just as air traffic regulation is based on the assumption that the planes are trying not to crash into one another, financial regulation is based on the assumption that people are trying to make money for themselves, not to destroy it for other people.

When I think about market regulation, I’m always reminded of a saying of Édouard Herriot, the former mayor of Lyon. He said that local government was like an andouillette sausage; it had to stink a little bit of shit, but not too much. Financial markets aren’t video games, they aren’t democratic and small investors aren’t the backbone of capitalism. They’re nasty places with extremely complicated rules, which only work to the extent that the people involved in them trust one another. Speculation is genuinely necessary on a stock market – without it, you could be waiting days for someone to take up your offer when you wanted to buy or sell shares. But it’s a necessary evil, and it needs to be limited. It’s a shame that the Redditors found this out the hard way.

Towards the end of 1636, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in the Netherlands. The concept of a lockdown was not really established at the time, but merchant trade slowed to a trickle. Idle young men in the town of Haarlem gathered in taverns, and looked for amusement in one of the few commodities still trading – contracts for the delivery of flower bulbs the following spring. What ensued is often regarded as the first financial bubble in recorded history – the “tulip mania”.

Nearly 400 years later, something similar has happened in the US stock market. This week, the share price of a company called GameStop – an unexceptional retailer that appears to have been surprised and confused by the whole episode – became the battleground between some of the biggest names in finance and a few hundred bored (mostly) bros exchanging messages on the WallStreetBets forum, part of the sprawling discussion site Reddit.

The rubble is still bouncing in this particular episode, but the broad shape of what’s happened is not unfamiliar. Reasoning that a business model based on selling video game DVDs through shopping malls might not have very bright prospects, several of New York’s finest hedge funds bet against GameStop’s share price. The Reddit crowd appears to have decided that this was unfair and that they should fight back on behalf of gamers. They took the opposite side of the trade and pushed the price up, using derivatives and brokerage credit in surprisingly sophisticated ways to maximise their firepower.

To everyone’s surprise, the crowd won; the hedge funds’ risk management processes kicked in, and they were forced to buy back their negative positions, pushing the price even higher. But the stock exchanges have always frowned on this sort of concerted action, and on the use of leverage to manipulate the market. The sheer volume of orders had also grown well beyond the capacity of the small, fee-free brokerages favoured by the WallStreetBets crowd. Credit lines were pulled, accounts were frozen and the retail crowd were forced to sell; yesterday the price gave back a large proportion of its gains.

To people who know a lot about stock exchange regulation and securities settlement, this outcome was quite inevitable – it’s part of the reason why things like this don’t happen every day. To a lot of American Redditors, though, it was a surprising introduction to the complexity of financial markets, taking place in circumstances almost perfectly designed to convince them that the system is rigged for the benefit of big money.

Corners, bear raids and squeezes, in the industry jargon, have been around for as long as stock markets – in fact, as British hedge fund legend Paul Marshall points out in his book Ten and a Half Lessons From Experience something very similar happened last year at the start of the coronavirus lockdown, centred on a suddenly unemployed sports bookmaker called Dave Portnoy. But the GameStop affair exhibits some surprising new features.

Most importantly, it was a largely self-organising phenomenon. For most of stock market history, orchestrating a pool of people to manipulate markets has been something only the most skilful could achieve. Some of the finest buildings in New York were erected on the proceeds of this rare talent, before it was made illegal. The idea that such a pool could coalesce so quickly and without any obvious sign of a single controlling mind is brand new and ought to worry us a bit.

And although some of the claims made by contributors to WallStreetBets that they represent the masses aren’t very convincing – although small by hedge fund standards, many of them appear to have five-figure sums to invest – it’s unfamiliar to say the least to see a pool motivated by rage or other emotions as opposed to the straightforward desire to make money. Just as air traffic regulation is based on the assumption that the planes are trying not to crash into one another, financial regulation is based on the assumption that people are trying to make money for themselves, not to destroy it for other people.

When I think about market regulation, I’m always reminded of a saying of Édouard Herriot, the former mayor of Lyon. He said that local government was like an andouillette sausage; it had to stink a little bit of shit, but not too much. Financial markets aren’t video games, they aren’t democratic and small investors aren’t the backbone of capitalism. They’re nasty places with extremely complicated rules, which only work to the extent that the people involved in them trust one another. Speculation is genuinely necessary on a stock market – without it, you could be waiting days for someone to take up your offer when you wanted to buy or sell shares. But it’s a necessary evil, and it needs to be limited. It’s a shame that the Redditors found this out the hard way.

Tuesday, 2 June 2020

The Power of Crowds

Even before the pandemic, mass gatherings were under threat from draconian laws and corporate seizure of public space. Yet history shows that the crowd always finds a way to return. By Dan Hancox in The Guardian

As lockdown loomed in March, I became obsessed with a football anthem for a team 400 miles away. I had read a news story about Edinburgh residents singing a Proclaimers song called Sunshine on Leith from their balconies. I didn’t know the song, and when I looked it up, I found a glorious video of 26,000 Hibernian fans singing it in a sun-drenched Hampden Park, after a long-hoped-for Scottish Cup win in 2016. Both teams had left the pitch, and the Rangers’ half of the stadium was empty. It looked like a concert in which the fans were simultaneously the performer and the audience.

I was entranced. I watched it again, and again. The sight and sound of this collective joy was transcendent: tens of thousands of green-and-white scarves held aloft, everyone belting out the song at the tops of their lungs. When the crowd hits the chorus, the volume levels on the shaky smartphone video blow their limit, exploding into a delirious roar of noise. I thought of something that one of the leaders of the nationwide “Tuneless Choirs” – specifically for people who can’t sing – once said: “If you get enough people singing together, with enough volume, it always sounds good.” Our individual failings are submerged; we become greater than the sum of our meagre parts. Anthems sung alone sound thin and absurd – think of the spectacle of a pop star bellowing the Star-Spangled Banner at the Super Bowl. Anthems need the warmth of harmony, or even the chafing of dissonance. They need the full sound of bodies brushing up against each other in pride, joy or righteousness.

Sunshine on Leith is ostensibly a love song, but in this instance, it wasn’t being sung to a lover, or to the victorious Hibs players, or to the football club, or to Leith – the 26,000 singers seemed to be addressing each other. In their many and varied voices, they had transformed it into a love song to the crowd: “While I’m worth my room on this Earth, I will be with you / While the chief puts sunshine on Leith, I’ll thank him for his work, and your birth and my birth.” In the YouTube comments, fans of other clubs, from Millwall to Lyon – and even Hibs’ arch-rivals Hearts – congratulate the Hibbies; not on the cup victory, not on the performance of the team, but that of the crowd. “Even the riot police horses shedding tears there,” observes one.

As the lockdown commenced, I found myself cueing up other songs that reminded me of crowds. In the way a single snatch of melody can instantly remind you of an ex, or an old friend, I wanted songs that reminded me of what it’s like to be with thousands of strangers. I listened to Drake’s Nice for What and Koffee’s Toast, which took me back to swaying tipsily in the crush of Notting Hill carnival, of being giddily overwhelmed, as the juddering sub-bass moved in waves through a million ribcages.

Perhaps this is too pessimistic. The 21st-century domestication of the crowd does not in itself snuff out its power. The experience of being part of a crowd can still change us in all manner of unexpected ways. If one thing should be retained from academics’ debunking of the myth of the crowd as a single beast with one brain and a thousand limbs, it is precisely that the diversity of the individuals within the crowd is what makes it so vital.

Far from behaving as one, everyone has different cooperation thresholds for participation, and there are some who by their nature will always be the first in the pool. For better or worse, crowds empower more shy or conservative people to do what they might not have done otherwise: to pronounce their political beliefs or proclaim their sexual orientation in public, to sing about their heartfelt feelings for Sergio Agüero, to occupy a bank, to throw a brick, to fight with strangers, to dance to Abba in the concourse of a major intercity railway station.

Being a crowd member is not a muscle that will atrophy through lack of use – our knack for it, and need for it, has a much longer history than the months we will be required to keep our physical distance. The desire to be part of the crowd is a part of who we are, and it will not be dispersed so easily.

As lockdown loomed in March, I became obsessed with a football anthem for a team 400 miles away. I had read a news story about Edinburgh residents singing a Proclaimers song called Sunshine on Leith from their balconies. I didn’t know the song, and when I looked it up, I found a glorious video of 26,000 Hibernian fans singing it in a sun-drenched Hampden Park, after a long-hoped-for Scottish Cup win in 2016. Both teams had left the pitch, and the Rangers’ half of the stadium was empty. It looked like a concert in which the fans were simultaneously the performer and the audience.

I was entranced. I watched it again, and again. The sight and sound of this collective joy was transcendent: tens of thousands of green-and-white scarves held aloft, everyone belting out the song at the tops of their lungs. When the crowd hits the chorus, the volume levels on the shaky smartphone video blow their limit, exploding into a delirious roar of noise. I thought of something that one of the leaders of the nationwide “Tuneless Choirs” – specifically for people who can’t sing – once said: “If you get enough people singing together, with enough volume, it always sounds good.” Our individual failings are submerged; we become greater than the sum of our meagre parts. Anthems sung alone sound thin and absurd – think of the spectacle of a pop star bellowing the Star-Spangled Banner at the Super Bowl. Anthems need the warmth of harmony, or even the chafing of dissonance. They need the full sound of bodies brushing up against each other in pride, joy or righteousness.

Sunshine on Leith is ostensibly a love song, but in this instance, it wasn’t being sung to a lover, or to the victorious Hibs players, or to the football club, or to Leith – the 26,000 singers seemed to be addressing each other. In their many and varied voices, they had transformed it into a love song to the crowd: “While I’m worth my room on this Earth, I will be with you / While the chief puts sunshine on Leith, I’ll thank him for his work, and your birth and my birth.” In the YouTube comments, fans of other clubs, from Millwall to Lyon – and even Hibs’ arch-rivals Hearts – congratulate the Hibbies; not on the cup victory, not on the performance of the team, but that of the crowd. “Even the riot police horses shedding tears there,” observes one.

As the lockdown commenced, I found myself cueing up other songs that reminded me of crowds. In the way a single snatch of melody can instantly remind you of an ex, or an old friend, I wanted songs that reminded me of what it’s like to be with thousands of strangers. I listened to Drake’s Nice for What and Koffee’s Toast, which took me back to swaying tipsily in the crush of Notting Hill carnival, of being giddily overwhelmed, as the juddering sub-bass moved in waves through a million ribcages.

Notting Hill carnival in 2012. Photograph: Miles Davies/Alamy Stock Photo

I missed the disinhibition of dancing in a dark, low-ceilinged club. I missed screaming into the cold winter air of the AFC Wimbledon terraces about an outrageous refereeing decision. I missed the joy of chanting and feeling my own thin voice being made whole by others joining it in unison. I missed the tingling mixture of anxiety and vertigo of the moment you first step out into a festival or football or carnival or protest crowd, a feeling of over-stimulation, the ripples of noise and colour jostling for your attention, the anticipation of being subsumed in the crowd and yet powered up by it – of losing a part of yourself, and your independence, and being glad to. I missed the strange alchemy of congregation, when your brain pulses with the validation of being with so many people who have chosen the same path. How could I be wrong? Look, all these people are here, too.

While many of us were missing crowds, the realities of Covid-19 meant they had taken on a completely new meaning. Gathering with others was suddenly, paradoxically antisocial: it suggested you were careless about viral transmission of a deadly disease, more interested in your own short-term social needs than the lives of strangers. The very sight of a crowd suddenly seemed alarming. We shook our heads at rumours of parties, and shared pictures of Cheltenham festival or the Stereophonics’ Cardiff gigs as if they were clips from horror films. Festivals, congregations, assemblies, raves, processions, choirs, rallies, demonstrations, audiences in stadiums, halls, clubs, theatres and cinemas – gatherings of any kind became fatal. As lockdown begins to ease, people are again gathering to socialise in parks and on beaches, and to rail against injustice in Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion protests, but crowds as we used to know them won’t be coming back for many months to come.

While the pandemic has made exceptional demands of us, even before the Covid-19 lockdown, crowds have been under threat. We were becoming ever more atomised, and pushed further into our homes, and crowds were becoming more domesticated, enclosed, surveilled and expensive to be a part of. Our opportunities to gather freely, in both senses of the word, have greatly diminished since the 90s. And yet, throughout human history, there has always been something pleasingly resilient about the crowd: however many new ways are found to disperse it, it will always find a way to reconvene.

Crowds have always had a bad rap: there is no gentle mob, no friendly pack. The same disinhibition that allows for moments of great joy can also enable grotesque crimes. The people who gathered to watch lynchings in the US, or recent attacks on Muslims by groups of Hindu nationalists in India, were not just bystanders but participants. Their presence and acquiescence helped make the violence possible. And just as the people at the back of the crowd empower those at the front, the reverse can be true. The hooligan firm leader who throws the first cafe chair across a moonlit plaza on a balmy European away day makes it easier for more timid members of the crowd to cross their own “cooperation threshold” and join in.

Even celebratory or worshipful crowds can go wrong, and when they do, they generate an unmatched horror. Few things strike fear like the the idea of mass panic, few words as chilling as “caught up in a stampede” or “trampled to death”. The horror of the 96 dead at Hillsborough in 1989, or the 21 suffocated at the 2010 Berlin Love Parade, or the 2,400 killed in a crowd collapse at the 2015 Hajj, gnaws at something deep in our psyches. For some people, even a peaceful and orderly crowd can be scary, triggering intense anxiety or PTSD.

Informed by tragedies, uprisings and protests alike, for a long time crowds were seen as inherently dangerous and lobotomising. But during the past couple of decades, thanks to work by social psychologists, behavioural scientists and anthropologists, a new understanding of the complexity of crowd behaviour has become increasingly influential.

I missed the disinhibition of dancing in a dark, low-ceilinged club. I missed screaming into the cold winter air of the AFC Wimbledon terraces about an outrageous refereeing decision. I missed the joy of chanting and feeling my own thin voice being made whole by others joining it in unison. I missed the tingling mixture of anxiety and vertigo of the moment you first step out into a festival or football or carnival or protest crowd, a feeling of over-stimulation, the ripples of noise and colour jostling for your attention, the anticipation of being subsumed in the crowd and yet powered up by it – of losing a part of yourself, and your independence, and being glad to. I missed the strange alchemy of congregation, when your brain pulses with the validation of being with so many people who have chosen the same path. How could I be wrong? Look, all these people are here, too.

While many of us were missing crowds, the realities of Covid-19 meant they had taken on a completely new meaning. Gathering with others was suddenly, paradoxically antisocial: it suggested you were careless about viral transmission of a deadly disease, more interested in your own short-term social needs than the lives of strangers. The very sight of a crowd suddenly seemed alarming. We shook our heads at rumours of parties, and shared pictures of Cheltenham festival or the Stereophonics’ Cardiff gigs as if they were clips from horror films. Festivals, congregations, assemblies, raves, processions, choirs, rallies, demonstrations, audiences in stadiums, halls, clubs, theatres and cinemas – gatherings of any kind became fatal. As lockdown begins to ease, people are again gathering to socialise in parks and on beaches, and to rail against injustice in Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion protests, but crowds as we used to know them won’t be coming back for many months to come.

While the pandemic has made exceptional demands of us, even before the Covid-19 lockdown, crowds have been under threat. We were becoming ever more atomised, and pushed further into our homes, and crowds were becoming more domesticated, enclosed, surveilled and expensive to be a part of. Our opportunities to gather freely, in both senses of the word, have greatly diminished since the 90s. And yet, throughout human history, there has always been something pleasingly resilient about the crowd: however many new ways are found to disperse it, it will always find a way to reconvene.

Crowds have always had a bad rap: there is no gentle mob, no friendly pack. The same disinhibition that allows for moments of great joy can also enable grotesque crimes. The people who gathered to watch lynchings in the US, or recent attacks on Muslims by groups of Hindu nationalists in India, were not just bystanders but participants. Their presence and acquiescence helped make the violence possible. And just as the people at the back of the crowd empower those at the front, the reverse can be true. The hooligan firm leader who throws the first cafe chair across a moonlit plaza on a balmy European away day makes it easier for more timid members of the crowd to cross their own “cooperation threshold” and join in.

Even celebratory or worshipful crowds can go wrong, and when they do, they generate an unmatched horror. Few things strike fear like the the idea of mass panic, few words as chilling as “caught up in a stampede” or “trampled to death”. The horror of the 96 dead at Hillsborough in 1989, or the 21 suffocated at the 2010 Berlin Love Parade, or the 2,400 killed in a crowd collapse at the 2015 Hajj, gnaws at something deep in our psyches. For some people, even a peaceful and orderly crowd can be scary, triggering intense anxiety or PTSD.

Informed by tragedies, uprisings and protests alike, for a long time crowds were seen as inherently dangerous and lobotomising. But during the past couple of decades, thanks to work by social psychologists, behavioural scientists and anthropologists, a new understanding of the complexity of crowd behaviour has become increasingly influential.

A depiction of the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester in 1819, when cavalry charged on a crowd at a political rally. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

For most of us, a crowd can be an alluring thing, because the desire to be among the throng seems to be innate. Gathering together for ritualistic celebrations – dancing, chanting, festivalling, costuming, singing, marching – goes back almost as far as we have any record of human behaviour. In 2003, 13,000-year-old cave paintings were discovered in Nottinghamshire that seemed to show “conga lines” of dancing women. According to the archeologist Paul Pettitt, the paintings matched others across Europe, indicating that they were part of a continent-wide Paleolithic culture of collective singing and dancing.

In Barbara Ehrenreich’s 2007 book Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, she draws on the work of anthropologists including Robin Dunbar to argue that dancing and music-making was a social glue that helped stone-age families join together in groups larger than the family unit, to hunt and protect themselves from predators. For Ehrenreich, rituals of collective joy are as intrinsic to human development as speech. More recent experiments by Dunbar and his colleagues have suggested that the capacity of singing together to bond groups of strangers shows it “may have played a role in the evolutionary success of modern humans over their early relatives”.

The power of crowds has long fixated religious and secular leaders alike, who have sought to harness communal energy for their own glorification, or to tame mass gatherings when they start to take on a momentum of their own. Ehrenreich records the medieval Christian church’s long battle to eradicate unruly, ecstatic or immoderate dancing from the congregation. In later centuries, as the reformation and industrial revolution proceeded, festivals, feast days, sports, revels and ecstatic rituals of countless kinds were outlawed for their tendency to result in drunken, pagan or otherwise ungodly behaviour. Between the 17th and 20th centuries, there were “literally thousands of acts of legislation introduced which attempted to outlaw carnival and popular festivity from European life,” wrote Peter Stallybrass and Allon White in The Politics and Poetics of Transgression.

It wasn’t until the 19th century, as industrialising cities exploded in size, that the formal study of crowd psychology and herd behaviour emerged. Reflecting on the French Revolution a century earlier, thinkers such as Gustave Le Bon helped promote the idea that a crowd is always on the verge of becoming a mob. Stirred up by agitators, crowds could quickly turn to violence, sweeping up even good, upstanding citizens in their collective madness. “By the mere fact that he forms part of an organised crowd,” Le Bon wrote, “a man descends several rungs in the ladder of civilisation.”

While the discipline of crowd psychology has moved on considerably since the days of Le Bon, these early theories still retain their hold, says Clifford Stott, a professor of social psychology at Keele University. Much of the media coverage of the riots that broke out across England in 2011 echoed the explanations of the 19th-century pioneers of crowd psychology: they were a pathological intrusion into civilised society, a contagion, spread by agitators, of the normally stable and contented body politic. Focus fell, in particular, on ill-defined “criminal gangs” stirring things up, possibly coordinating things via BlackBerry Messenger. The foot soldiers – 30,000 people were thought to have participated – were depicted as feral thugs. Hordes. Animals. The frontpage headlines were clear: “Rule of the mob”, “Yob rule”, “Flaming morons”. Purportedly liberal voices clamoured for David Cameron to send in the army. Shoot looters on sight. Wheel in the water cannon.

For most of us, a crowd can be an alluring thing, because the desire to be among the throng seems to be innate. Gathering together for ritualistic celebrations – dancing, chanting, festivalling, costuming, singing, marching – goes back almost as far as we have any record of human behaviour. In 2003, 13,000-year-old cave paintings were discovered in Nottinghamshire that seemed to show “conga lines” of dancing women. According to the archeologist Paul Pettitt, the paintings matched others across Europe, indicating that they were part of a continent-wide Paleolithic culture of collective singing and dancing.

In Barbara Ehrenreich’s 2007 book Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, she draws on the work of anthropologists including Robin Dunbar to argue that dancing and music-making was a social glue that helped stone-age families join together in groups larger than the family unit, to hunt and protect themselves from predators. For Ehrenreich, rituals of collective joy are as intrinsic to human development as speech. More recent experiments by Dunbar and his colleagues have suggested that the capacity of singing together to bond groups of strangers shows it “may have played a role in the evolutionary success of modern humans over their early relatives”.

The power of crowds has long fixated religious and secular leaders alike, who have sought to harness communal energy for their own glorification, or to tame mass gatherings when they start to take on a momentum of their own. Ehrenreich records the medieval Christian church’s long battle to eradicate unruly, ecstatic or immoderate dancing from the congregation. In later centuries, as the reformation and industrial revolution proceeded, festivals, feast days, sports, revels and ecstatic rituals of countless kinds were outlawed for their tendency to result in drunken, pagan or otherwise ungodly behaviour. Between the 17th and 20th centuries, there were “literally thousands of acts of legislation introduced which attempted to outlaw carnival and popular festivity from European life,” wrote Peter Stallybrass and Allon White in The Politics and Poetics of Transgression.

It wasn’t until the 19th century, as industrialising cities exploded in size, that the formal study of crowd psychology and herd behaviour emerged. Reflecting on the French Revolution a century earlier, thinkers such as Gustave Le Bon helped promote the idea that a crowd is always on the verge of becoming a mob. Stirred up by agitators, crowds could quickly turn to violence, sweeping up even good, upstanding citizens in their collective madness. “By the mere fact that he forms part of an organised crowd,” Le Bon wrote, “a man descends several rungs in the ladder of civilisation.”

While the discipline of crowd psychology has moved on considerably since the days of Le Bon, these early theories still retain their hold, says Clifford Stott, a professor of social psychology at Keele University. Much of the media coverage of the riots that broke out across England in 2011 echoed the explanations of the 19th-century pioneers of crowd psychology: they were a pathological intrusion into civilised society, a contagion, spread by agitators, of the normally stable and contented body politic. Focus fell, in particular, on ill-defined “criminal gangs” stirring things up, possibly coordinating things via BlackBerry Messenger. The foot soldiers – 30,000 people were thought to have participated – were depicted as feral thugs. Hordes. Animals. The frontpage headlines were clear: “Rule of the mob”, “Yob rule”, “Flaming morons”. Purportedly liberal voices clamoured for David Cameron to send in the army. Shoot looters on sight. Wheel in the water cannon.

Riots in Hackney, east London in August 2011. Photograph: Luke Macgregor/Reuters

“What we need to recognise is that from a scientific perspective, classical [crowd] theory has no validity,” says Stott. “It doesn’t explain or predict the behaviours it purports to explain and predict. And yet everywhere you look, the narrative is still there.” The reason, he argues, is straightforward: “It’s very, very convenient for dominant and powerful groups,” Stott says. “It pathologises, decontextualises and renders meaningless crowd violence, and therefore legitimises its repression.” As Stott notes, by shifting the blame to the madness of crowds, it also conveniently allows the powerful to avoid scrutinising their own responsibility for the violence. Last week, when the US attorney general blamed “outside agitators” for stirring up violence, and Donald Trump referred to “professionally managed” “thugs”, they were drawing on exactly the ideas that Le Bon sketched out in the 19th century.

In recent decades, detailed analytical research has produced ever-more sophisticated insights into crowd behaviour, many of which disprove these long-standing assumptions. “Crowds have an amazing ability to police themselves, self-regulate, and actually display a lot of pro-social behaviour, supporting others in their group,” says Anne Templeton, an academic at Edinburgh University who studies crowd psychology. She points to the 2017 Manchester Arena terrorist attack, in which CCTV footage showed members of the public performing first aid on the wounded before emergency services arrived, and Mancunians rushed to provide food, shelter, transport and emotional support for the victims. “People provide an amazing amount of help in emergencies to people they don’t know, especially when they’re part of an in-group.”

Strange things happen to our brains when we’re in a crowd we’ve chosen to be part of, says Templeton. We don’t just feel happier and more confident, we also have a lower threshold of disgust. This is why festivalgoers will happily share drinks (and by dint of their proximity, sweat) with strangers, or Hajj pilgrims will share the sometimes bloody razors used to shave their heads. In a crowd, we feel safer from harm.

If we now have a better grasp of the complexity of crowd dynamics, the core truth about them is relatively simple: they have the potential to magnify both the good and bad in us. The loss of self in a crowd can lead to unthinkable violence, just as it can ecstatic transcendence. What is striking is that, in recent decades, the latter has troubled the British establishment every bit as much as the former.

‘The open crowd is the true crowd,” wrote Elias Canetti in his 1960 book Crowds and Power – “the crowd abandoning itself freely to its natural urge for growth”, rather than those hemmed in by authorities, limited in shape and size. The Sermon on the Mount, he writes, was delivered to an open crowd. The obsequious flock, the brainwashed cult, the army marching in lock-step, is a world away from a fluid, democratic, sometimes anarchic congregation of the people. These open crowds have become harder to find, and harder to keep open.

Contemporary Britain’s idea of the crowd was formed by two explosions in unruly mass culture at the end of the last century. First, by 70s and 80s football fandom and its manifold sins, and the avoidable tragedy of Hillsborough – a tragedy created by the authorities’ views of the crowd as animalistic thugs, a fear and loathing that permeated the media, police, political class and football authorities. And second, by the acid house explosion and rave scene of the late 80s and early 90s, a subcultural surge of illegal or at least illicit “free parties” in fields and warehouses across the country. Both cultures flourished in spite of widespread media demonisation, both fought the law – and in both cases, the law won. Things have never been the same since for people who wish to assemble on their own terms.

The policing, containment and enclosure of “free” raves is particularly instructive, suggesting that the authorities fear a happy crowd as much as a pitchfork-carrying one. For the novelist Hari Kunzru, reflecting on his 90s youth a few years ago, approaching the site of a rave, feeling “the bass pulsing up ahead, the excitement was almost unbearable. A mass of dancers lifting up like a single body … [an] ecstatic fantasy of community, a zone where we were networked with each other, rather than with the office switchboard.”

“What we need to recognise is that from a scientific perspective, classical [crowd] theory has no validity,” says Stott. “It doesn’t explain or predict the behaviours it purports to explain and predict. And yet everywhere you look, the narrative is still there.” The reason, he argues, is straightforward: “It’s very, very convenient for dominant and powerful groups,” Stott says. “It pathologises, decontextualises and renders meaningless crowd violence, and therefore legitimises its repression.” As Stott notes, by shifting the blame to the madness of crowds, it also conveniently allows the powerful to avoid scrutinising their own responsibility for the violence. Last week, when the US attorney general blamed “outside agitators” for stirring up violence, and Donald Trump referred to “professionally managed” “thugs”, they were drawing on exactly the ideas that Le Bon sketched out in the 19th century.

In recent decades, detailed analytical research has produced ever-more sophisticated insights into crowd behaviour, many of which disprove these long-standing assumptions. “Crowds have an amazing ability to police themselves, self-regulate, and actually display a lot of pro-social behaviour, supporting others in their group,” says Anne Templeton, an academic at Edinburgh University who studies crowd psychology. She points to the 2017 Manchester Arena terrorist attack, in which CCTV footage showed members of the public performing first aid on the wounded before emergency services arrived, and Mancunians rushed to provide food, shelter, transport and emotional support for the victims. “People provide an amazing amount of help in emergencies to people they don’t know, especially when they’re part of an in-group.”

Strange things happen to our brains when we’re in a crowd we’ve chosen to be part of, says Templeton. We don’t just feel happier and more confident, we also have a lower threshold of disgust. This is why festivalgoers will happily share drinks (and by dint of their proximity, sweat) with strangers, or Hajj pilgrims will share the sometimes bloody razors used to shave their heads. In a crowd, we feel safer from harm.

If we now have a better grasp of the complexity of crowd dynamics, the core truth about them is relatively simple: they have the potential to magnify both the good and bad in us. The loss of self in a crowd can lead to unthinkable violence, just as it can ecstatic transcendence. What is striking is that, in recent decades, the latter has troubled the British establishment every bit as much as the former.

‘The open crowd is the true crowd,” wrote Elias Canetti in his 1960 book Crowds and Power – “the crowd abandoning itself freely to its natural urge for growth”, rather than those hemmed in by authorities, limited in shape and size. The Sermon on the Mount, he writes, was delivered to an open crowd. The obsequious flock, the brainwashed cult, the army marching in lock-step, is a world away from a fluid, democratic, sometimes anarchic congregation of the people. These open crowds have become harder to find, and harder to keep open.

Contemporary Britain’s idea of the crowd was formed by two explosions in unruly mass culture at the end of the last century. First, by 70s and 80s football fandom and its manifold sins, and the avoidable tragedy of Hillsborough – a tragedy created by the authorities’ views of the crowd as animalistic thugs, a fear and loathing that permeated the media, police, political class and football authorities. And second, by the acid house explosion and rave scene of the late 80s and early 90s, a subcultural surge of illegal or at least illicit “free parties” in fields and warehouses across the country. Both cultures flourished in spite of widespread media demonisation, both fought the law – and in both cases, the law won. Things have never been the same since for people who wish to assemble on their own terms.

The policing, containment and enclosure of “free” raves is particularly instructive, suggesting that the authorities fear a happy crowd as much as a pitchfork-carrying one. For the novelist Hari Kunzru, reflecting on his 90s youth a few years ago, approaching the site of a rave, feeling “the bass pulsing up ahead, the excitement was almost unbearable. A mass of dancers lifting up like a single body … [an] ecstatic fantasy of community, a zone where we were networked with each other, rather than with the office switchboard.”

An acid house party in Berkshire in 1989. Photograph: Rex/Shutterstock

The culmination of the rave era, and the beginning of its end, was the epochal 1992 Castlemorton Common festival, a week-long, outdoor free party in Worcestershire, with numbers in excess of 20,000. Writing about it in the Evening Standard, Anthony Burgess summed up the establishment mood, railing against “the megacrowd, reducing the individual intelligence to that of an amoeba”. One man’s escapist fantasy of community is another’s vision of civilisational collapse, and the Thatcher-into-Major-era junta of the tabloid press, police, landowners and the Conservative party made it their business to disperse rave’s congregation of squatters, dropouts, drug-takers, hippies, hunt saboteurs, anti-road protesters and travellers.

In 1994, parliament passed the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, which outlawed any open air, night-time public congregation around amplified music. “For this purpose,” the act specified, “‘music’ includes sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” Any ambiguity about the target of the legislation was wiped away during the House of Lords debate on the bill. The Conservative deputy leader of the House, the hereditary peer Earl Ferrers, suggested an amendment “which would catch a rave party but would not also catch a Pavarotti concert, a barbecue or people having a dance in the early hours of the evening”. I do hope, replied another, that they would not risk jailing Pavarotti under the new legislation.

For the ravers, what had begun as a transcendent celebration turned into a question of the right to assemble in the first place. Before the bill passed into law, three elegiac “Kill the Bill” protest-parties took place in 1994, drawing tens of thousands, and culminating in October when bare-chested, dreadlocked protesters shook the gates of Downing Street to a soundtrack of whistles, cheers and repetitive beats. In archival video from that day, a protester clambers to the top of the gates and sits there nonchalantly smoking a fag, while police in short-sleeved shirts look on in horror. It is a telling time capsule, because it is hard to imagine any crowd of protesters getting this close to No 10 ever again.

The culmination of the rave era, and the beginning of its end, was the epochal 1992 Castlemorton Common festival, a week-long, outdoor free party in Worcestershire, with numbers in excess of 20,000. Writing about it in the Evening Standard, Anthony Burgess summed up the establishment mood, railing against “the megacrowd, reducing the individual intelligence to that of an amoeba”. One man’s escapist fantasy of community is another’s vision of civilisational collapse, and the Thatcher-into-Major-era junta of the tabloid press, police, landowners and the Conservative party made it their business to disperse rave’s congregation of squatters, dropouts, drug-takers, hippies, hunt saboteurs, anti-road protesters and travellers.

In 1994, parliament passed the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, which outlawed any open air, night-time public congregation around amplified music. “For this purpose,” the act specified, “‘music’ includes sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” Any ambiguity about the target of the legislation was wiped away during the House of Lords debate on the bill. The Conservative deputy leader of the House, the hereditary peer Earl Ferrers, suggested an amendment “which would catch a rave party but would not also catch a Pavarotti concert, a barbecue or people having a dance in the early hours of the evening”. I do hope, replied another, that they would not risk jailing Pavarotti under the new legislation.

For the ravers, what had begun as a transcendent celebration turned into a question of the right to assemble in the first place. Before the bill passed into law, three elegiac “Kill the Bill” protest-parties took place in 1994, drawing tens of thousands, and culminating in October when bare-chested, dreadlocked protesters shook the gates of Downing Street to a soundtrack of whistles, cheers and repetitive beats. In archival video from that day, a protester clambers to the top of the gates and sits there nonchalantly smoking a fag, while police in short-sleeved shirts look on in horror. It is a telling time capsule, because it is hard to imagine any crowd of protesters getting this close to No 10 ever again.

Police bust a warehouse party circa 1997. Photograph: PYMCA/Universal Images Group/Getty

The Criminal Justice Act killed the free party scene, and like Hillsborough, its legacy is still felt to this day. In fact, it was only the beginning of a series of restrictions on free assembly. The past 25 years have been a challenging time for crowds, thanks to the rise of surveillance technology and privatisation of public space. During the 1990s, 78% of the Home Office crime prevention budget was spent on implementing CCTV – and a further £500m of public money was spent on it between 2000 and 2006. London became the most surveilled city in the world for a time, and even today no city outside China has more CCTV per head.

The explosion of CCTV is just one way the 21st-century city hampers the freedom of the crowd. Urban regeneration programmes are designed to channel us efficiently towards work and the shops – spaces built for Homo economicus, human beings interacting transactionally, rather as social citizens. What look like potential meeting grounds for crowds in the modern British city are often mirages: regeneration zones such as Spinningfields in Manchester, Liverpool One and More London have replaced genuine public spaces with privately owned public spaces. These are patrolled by security guards and underwritten by private rules and regulations, whereby the owners are perfectly entitled to ban gatherings and political protests, and move along whoever they like, whenever they like.

In 2011, when Occupy London attempted to set up camp in Paternoster Square, outside the London Stock Exchange, they were blocked by police barricades, enforcing an emergency high court injunction that established that the land was indeed private property. This was odd, the Observer’s architecture critic Rowan Moore wrote at the time, “as almost every architectural statement, planning application, and press release, in the protracted redevelopment of Paternoster Square, described this ‘private land’ as ‘public space’.”

If the average British city has undergone huge transformations since the Criminal Justice Act, then so have the people in it. Crowd behaviour in the 21st century has been conditioned by the new devices at our fingertips as much as the changing ground beneath our feet, or the laws that govern their movement. In his prescient 2002 book Smart Mobs, the critic Harold Rheingold identified new types of crowds that were able to act in concert even before they had met. He predicted a “social tsunami” to come from the next wave of mobile telecoms, pointing to the mass SMS chains in Manila that were used to coordinate the protests that overthrew the Philippine president Joseph Estrada in 2001.

While alienation and isolation are certainly hallmarks of modern life, when a crowd is needed, it springs into life. The 2009 Iran green revolution, the 2011 Arab Spring, the Occupy movement, the Spanish indignados and the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Turkey – all of these “movements of the squares” saw physical public space unexpectedly replenished with fresh, angry crowds that had established many of their initial networks and political education via the internet. “Online inspiration, offline perspiration”, as one slogan of the time put it.

These digitally enhanced tactics took over British streets in the winter of 2010, when student and anti-cuts protesters came out against the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition’s austerity policies and tripling of tuition fees. The police responded with the controversial crowd-control tactic of kettling – essentially imprisoning people outdoors between lines of riot police, without access to food, water, toilets, warm clothing or medical assistance, for hours at a time.

Kettling worked against the student protesters on several fronts, dampening their spirits, disincentivising future protests, riling up some to violence and thus delivering the government the PR victory they needed. “Is not the point of a kettle that it brings things to the boil?” David Lammy MP asked Theresa May, then the home secretary, at the time. But it also radicalised many of them, precisely because they had had their freedom to move restricted, pushing them to direct action tactics in defiance of the tactics proposed by the leaders of the National Union of Students.

The Criminal Justice Act killed the free party scene, and like Hillsborough, its legacy is still felt to this day. In fact, it was only the beginning of a series of restrictions on free assembly. The past 25 years have been a challenging time for crowds, thanks to the rise of surveillance technology and privatisation of public space. During the 1990s, 78% of the Home Office crime prevention budget was spent on implementing CCTV – and a further £500m of public money was spent on it between 2000 and 2006. London became the most surveilled city in the world for a time, and even today no city outside China has more CCTV per head.

The explosion of CCTV is just one way the 21st-century city hampers the freedom of the crowd. Urban regeneration programmes are designed to channel us efficiently towards work and the shops – spaces built for Homo economicus, human beings interacting transactionally, rather as social citizens. What look like potential meeting grounds for crowds in the modern British city are often mirages: regeneration zones such as Spinningfields in Manchester, Liverpool One and More London have replaced genuine public spaces with privately owned public spaces. These are patrolled by security guards and underwritten by private rules and regulations, whereby the owners are perfectly entitled to ban gatherings and political protests, and move along whoever they like, whenever they like.

In 2011, when Occupy London attempted to set up camp in Paternoster Square, outside the London Stock Exchange, they were blocked by police barricades, enforcing an emergency high court injunction that established that the land was indeed private property. This was odd, the Observer’s architecture critic Rowan Moore wrote at the time, “as almost every architectural statement, planning application, and press release, in the protracted redevelopment of Paternoster Square, described this ‘private land’ as ‘public space’.”

If the average British city has undergone huge transformations since the Criminal Justice Act, then so have the people in it. Crowd behaviour in the 21st century has been conditioned by the new devices at our fingertips as much as the changing ground beneath our feet, or the laws that govern their movement. In his prescient 2002 book Smart Mobs, the critic Harold Rheingold identified new types of crowds that were able to act in concert even before they had met. He predicted a “social tsunami” to come from the next wave of mobile telecoms, pointing to the mass SMS chains in Manila that were used to coordinate the protests that overthrew the Philippine president Joseph Estrada in 2001.

While alienation and isolation are certainly hallmarks of modern life, when a crowd is needed, it springs into life. The 2009 Iran green revolution, the 2011 Arab Spring, the Occupy movement, the Spanish indignados and the 2013 Gezi Park protests in Turkey – all of these “movements of the squares” saw physical public space unexpectedly replenished with fresh, angry crowds that had established many of their initial networks and political education via the internet. “Online inspiration, offline perspiration”, as one slogan of the time put it.

These digitally enhanced tactics took over British streets in the winter of 2010, when student and anti-cuts protesters came out against the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition’s austerity policies and tripling of tuition fees. The police responded with the controversial crowd-control tactic of kettling – essentially imprisoning people outdoors between lines of riot police, without access to food, water, toilets, warm clothing or medical assistance, for hours at a time.

Kettling worked against the student protesters on several fronts, dampening their spirits, disincentivising future protests, riling up some to violence and thus delivering the government the PR victory they needed. “Is not the point of a kettle that it brings things to the boil?” David Lammy MP asked Theresa May, then the home secretary, at the time. But it also radicalised many of them, precisely because they had had their freedom to move restricted, pushing them to direct action tactics in defiance of the tactics proposed by the leaders of the National Union of Students.

Mounted police drive their horses into protesters during student demonstrations in London in December 2010. Photograph: Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images

Academic Hannah Awcock attended the 2010 protests as a student, and now lectures on the history of protest at the University of Central Lancashire. She explained that throughout history, from the 1866 Hyde Park suffrage riots to the student demos, protest crowds have often pushed to go further than their organisers, or the authorities, will allow for. And yet, as febrile as the atmosphere around Brexit and austerity has been in the nine years since the student protests and London riots, large protests have appeared calmer, on the face of it at least. In the UK, “that really aggressive and confrontational policing that emerged post-9/11 seems to have diminished now,” Awcock said. “Maybe it’s because the protests themselves are less radical, but it’s also because there’s also been a turn towards more subtle methods of policing crowds, techniques like increased surveillance and intelligence gathering.”

The changes to crowd policing in the past decade owe a great deal to behind-the-scenes policy work by crowd psychologists. Clifford Stott has worked with police and football authorities for many years to discourage heavy-handed policing. One turning point, he told me, was the 2011 Liberal Democrat conference in Sheffield, where South Yorkshire police trialled Stott’s recommendations. Unlike Brighton, Liverpool, Birmingham or Manchester, the city was not used to hosting conferences for a party of government, and substantial student and anti-austerity protests were expected. In preparation, police established a new “dialogue unit” of Police Liaison Teams (PLTs) in blue tabards, recruiting individuals to move among the crowd talking to them, rather than policing in numbers from the outside.

“What we found was that these dialogue units were policing the police,” said Stott. “They were stopping unnecessary interventions. The PLTs were reassuring the commanders that an intervention wasn’t needed.” Instead of riot cops wading in, de-escalation and crowd self-regulation took over. Since then, Stott said, this approach has become more common. “Where the police have these capacities for dialogue and communication, there’s less disorder. It’s that simple.”

According to Ch Insp Melita Worswick of Greater Manchester police, this is part of a broader shift in crowd policing in the UK – away from the notion of enforcing “public order” towards an emphasis on public safety. “It’s really important to have the right people communicating with crowds,” she says. “This is about building on policing with consent, and knowing that if we don’t manage that right, it could result in disorder.” It’s also about learning to step back, rather than aggressively intervening at the first opportunity. “Sometimes taking no action is the right way,” says Worswick. It’s an approach that police in Glasgow have put into action for recent matches between Rangers and Celtic. Following advice from academics, they will now allow fans to jeer at each other for a while, because they know that’s part of the ritual, and won’t intervene unless it starts to get violent. Up to a point, at least, they trust the crowd members to self-regulate.

While this sounds like progress, the reality does not always match the rhetoric. Even Extinction Rebellion, which initially attempted to cultivate a friendly relationship with the police, and sought mass arrest as a tactic – later decried the Met’s “over-reach characterised by systematic discrimination, routine use of force, intimidation and physical harm” in hundreds of cases last year. Even more recently, the Met’s use of Covid-19 social-distancing legislation to make arrests at Sunday’s Black Lives Matter protest in London suggests that many elements in the police remain unwilling to step back from the crowd.

In place of the open crowd, nowadays we have come to understand a congregation of people primarily as a money-making opportunity. There is no greater evidence of the attenuated, monetised nature of the 21st-century crowd than the rise of the events industry. Events, in themselves, are of course not new inventions. But there are events, dear boy, and then there are Events: usually sponsored, probably with an admission fee, probably with a range of media partners, good for city-branding, good for tourism, orderly, pre-agreed, surveilled and dispersed at the agreed time. They have become an integral part of the contemporary city, and the reimagining of its citizens as income-generating instruments.

London & Partners, the public-private partnership set up by Boris Johnson in 2011 to promote the capital, estimates that event leisure tourism contributed £2.8bn to the city’s economy in 2015 alone, £644m of which was from overseas “events tourists”. Increasingly, people come not for the UK per se, but the things happening in it. Chief among these are sporting events, which generate more than 70% of major events-related spending in London (music is some way behind). Amid huge fanfare in the past few years, a growing number of major international NBA, NFL and MLB games have come to London. According to London & Partners, 250,000 people have attended “NFL on Regent Street”, which isn’t even an American Football game, just a promotional event for the idea of one.

Academic Hannah Awcock attended the 2010 protests as a student, and now lectures on the history of protest at the University of Central Lancashire. She explained that throughout history, from the 1866 Hyde Park suffrage riots to the student demos, protest crowds have often pushed to go further than their organisers, or the authorities, will allow for. And yet, as febrile as the atmosphere around Brexit and austerity has been in the nine years since the student protests and London riots, large protests have appeared calmer, on the face of it at least. In the UK, “that really aggressive and confrontational policing that emerged post-9/11 seems to have diminished now,” Awcock said. “Maybe it’s because the protests themselves are less radical, but it’s also because there’s also been a turn towards more subtle methods of policing crowds, techniques like increased surveillance and intelligence gathering.”

The changes to crowd policing in the past decade owe a great deal to behind-the-scenes policy work by crowd psychologists. Clifford Stott has worked with police and football authorities for many years to discourage heavy-handed policing. One turning point, he told me, was the 2011 Liberal Democrat conference in Sheffield, where South Yorkshire police trialled Stott’s recommendations. Unlike Brighton, Liverpool, Birmingham or Manchester, the city was not used to hosting conferences for a party of government, and substantial student and anti-austerity protests were expected. In preparation, police established a new “dialogue unit” of Police Liaison Teams (PLTs) in blue tabards, recruiting individuals to move among the crowd talking to them, rather than policing in numbers from the outside.

“What we found was that these dialogue units were policing the police,” said Stott. “They were stopping unnecessary interventions. The PLTs were reassuring the commanders that an intervention wasn’t needed.” Instead of riot cops wading in, de-escalation and crowd self-regulation took over. Since then, Stott said, this approach has become more common. “Where the police have these capacities for dialogue and communication, there’s less disorder. It’s that simple.”

According to Ch Insp Melita Worswick of Greater Manchester police, this is part of a broader shift in crowd policing in the UK – away from the notion of enforcing “public order” towards an emphasis on public safety. “It’s really important to have the right people communicating with crowds,” she says. “This is about building on policing with consent, and knowing that if we don’t manage that right, it could result in disorder.” It’s also about learning to step back, rather than aggressively intervening at the first opportunity. “Sometimes taking no action is the right way,” says Worswick. It’s an approach that police in Glasgow have put into action for recent matches between Rangers and Celtic. Following advice from academics, they will now allow fans to jeer at each other for a while, because they know that’s part of the ritual, and won’t intervene unless it starts to get violent. Up to a point, at least, they trust the crowd members to self-regulate.

While this sounds like progress, the reality does not always match the rhetoric. Even Extinction Rebellion, which initially attempted to cultivate a friendly relationship with the police, and sought mass arrest as a tactic – later decried the Met’s “over-reach characterised by systematic discrimination, routine use of force, intimidation and physical harm” in hundreds of cases last year. Even more recently, the Met’s use of Covid-19 social-distancing legislation to make arrests at Sunday’s Black Lives Matter protest in London suggests that many elements in the police remain unwilling to step back from the crowd.

In place of the open crowd, nowadays we have come to understand a congregation of people primarily as a money-making opportunity. There is no greater evidence of the attenuated, monetised nature of the 21st-century crowd than the rise of the events industry. Events, in themselves, are of course not new inventions. But there are events, dear boy, and then there are Events: usually sponsored, probably with an admission fee, probably with a range of media partners, good for city-branding, good for tourism, orderly, pre-agreed, surveilled and dispersed at the agreed time. They have become an integral part of the contemporary city, and the reimagining of its citizens as income-generating instruments.

London & Partners, the public-private partnership set up by Boris Johnson in 2011 to promote the capital, estimates that event leisure tourism contributed £2.8bn to the city’s economy in 2015 alone, £644m of which was from overseas “events tourists”. Increasingly, people come not for the UK per se, but the things happening in it. Chief among these are sporting events, which generate more than 70% of major events-related spending in London (music is some way behind). Amid huge fanfare in the past few years, a growing number of major international NBA, NFL and MLB games have come to London. According to London & Partners, 250,000 people have attended “NFL on Regent Street”, which isn’t even an American Football game, just a promotional event for the idea of one.

The plaza in front of City Hall in London, a privately owned and carefully controlled public space. Photograph: Steven Watt/Reuters

Where there are crowds, there are consumers, and in the absence of state support, commercial sponsorship (itself rebranded as “partnership”) tracks the events industry’s every move. Last year, the capital played host to the Virgin Money London Marathon, the Prudential RideLondon, the Guinness Six Nations and the EFG London Jazz Festival. Meanwhile, Pride in London somehow managed to rack up 73 “partners” in 2019, from headline sponsors Tesco to PlayStation, the Scouts, the London Stock Exchange, Revlon and Foxtons, amid criticisms that the politics has been drained out of it in favour of corporate “pinkwashing”.

It’s hard to refute the argument that the more carefully planned and managed a large event is, the safer it is for those inside it, and the more the crowd will enjoy it. Not only do you minimise the risk of injury or potential trouble, but everyone – not least the most vulnerable – benefits when you have accessibility for people with mobility issues, the right number of toilets, the right number of exits, the right transport access, good sightlines, food and water and childcare facilities. And a reasonable argument is often made by organisers of cultural festivals that sponsors pay for these things, and pay for events such as Notting Hill Carnival, Pride and Mela to stay free, and accessible to all. But it’s hard not to wonder if something is being lost along the way, in an era when venture capital-backed music video platform Boiler Room receives Arts Council funding to broker Notting Hill Carnival sponsorship deals and live-stream its intimate hedonism to the world; or popular, long-standing free community festivals such as south London’s Lambeth Country Show suddenly have a heavy security presence, prompting outrage and boycotts.

Where there are crowds, there are consumers, and in the absence of state support, commercial sponsorship (itself rebranded as “partnership”) tracks the events industry’s every move. Last year, the capital played host to the Virgin Money London Marathon, the Prudential RideLondon, the Guinness Six Nations and the EFG London Jazz Festival. Meanwhile, Pride in London somehow managed to rack up 73 “partners” in 2019, from headline sponsors Tesco to PlayStation, the Scouts, the London Stock Exchange, Revlon and Foxtons, amid criticisms that the politics has been drained out of it in favour of corporate “pinkwashing”.

It’s hard to refute the argument that the more carefully planned and managed a large event is, the safer it is for those inside it, and the more the crowd will enjoy it. Not only do you minimise the risk of injury or potential trouble, but everyone – not least the most vulnerable – benefits when you have accessibility for people with mobility issues, the right number of toilets, the right number of exits, the right transport access, good sightlines, food and water and childcare facilities. And a reasonable argument is often made by organisers of cultural festivals that sponsors pay for these things, and pay for events such as Notting Hill Carnival, Pride and Mela to stay free, and accessible to all. But it’s hard not to wonder if something is being lost along the way, in an era when venture capital-backed music video platform Boiler Room receives Arts Council funding to broker Notting Hill Carnival sponsorship deals and live-stream its intimate hedonism to the world; or popular, long-standing free community festivals such as south London’s Lambeth Country Show suddenly have a heavy security presence, prompting outrage and boycotts.

Perhaps this is too pessimistic. The 21st-century domestication of the crowd does not in itself snuff out its power. The experience of being part of a crowd can still change us in all manner of unexpected ways. If one thing should be retained from academics’ debunking of the myth of the crowd as a single beast with one brain and a thousand limbs, it is precisely that the diversity of the individuals within the crowd is what makes it so vital.

Far from behaving as one, everyone has different cooperation thresholds for participation, and there are some who by their nature will always be the first in the pool. For better or worse, crowds empower more shy or conservative people to do what they might not have done otherwise: to pronounce their political beliefs or proclaim their sexual orientation in public, to sing about their heartfelt feelings for Sergio Agüero, to occupy a bank, to throw a brick, to fight with strangers, to dance to Abba in the concourse of a major intercity railway station.

Being a crowd member is not a muscle that will atrophy through lack of use – our knack for it, and need for it, has a much longer history than the months we will be required to keep our physical distance. The desire to be part of the crowd is a part of who we are, and it will not be dispersed so easily.

Thursday, 28 February 2019

Think like a civilisation

The biggest casualty of unquestioning enthusiasm for war is democracy and rational thought writes Shiv Vishwanathan

This essay is a piece of dissent at a time when dissent may not be welcome. It is an attempt to look at what I call the Pulwama syndrome, after India’s bombing of terrorist camps in Pakistan. There is an air of achievement and competence, a feeling that we have given a fitting reply to Pakistan. Newspapers have in unison supported the government, and citizens, from actors to cricketers, have been content in stating their loyalty, literally issuing certificates to the government. Yet watching all this, I feel a deep sense of unease, a feeling that India is celebrating a moment which needs to be located in a different context.

Peace needs courage

It reminded me of something that happened when I was in school. I had just come back from a war movie featuring Winston Churchill. I came back home excitedly and told my father about Churchill. He smiled sadly and said, “Churchill was a bully. He was not fit to touch Gandhi’s chappals.” He then added thoughtfully that “war creates a schoolboy loyalty, half boy scout, half mob”, which becomes epidemic. “Peace,” he said, “demands a courage few men have.” I still remember these lines, and I realised their relevance for the events this week.

One sees an instant unity which is almost miraculous. This sense of unity does not tolerate difference. People take loyalty literally and become paranoid. Crowds attack a long-standing bakery to remove the word ‘Karachi’ from its signage. War becomes an evangelical issue as each man desperately competes to prove his loyalty. Doubt and dissent become impossible, rationality is rare, and pluralism a remote possibility. There is a sense of solidarity with the ruling regime which is surreal. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who was encrusted with doubts a week before, appears like an untarnished hero. Even the cynicism around these attitudes is ignored. One watches with indifference as Bharatiya Janata Party president Amit Shah virtually claims that security and war are part of his vote bank.

Thought becomes a casualty as people conflate terms such as Kashmiri, Pakistani and Muslim while threatening citizens peacefully pursuing their livelihood. One watches aghast as India turns war into a feud, indifferent to a wider conflagration. The whole country lives from event to event and TV becomes hysterical, not knowing the difference between war and cricket. It is a moment when we congratulate ourselves as a nation, forgetting that we are also a civilisation. In this movement of drum-beating, where jingoism as patriotism is the order of the day, a dissenting voice is not welcome. But dissent demands that one faces one’s fellow citizens with probably more courage than one needs to face the enemy. How does one begin a conversation, create a space for a more critical perspective?

What war feels like

Sadly, India as a country has not experienced war as a totality, unlike Europe or other countries in Asia such as Vietnam or Afghanistan. War has always been an activity at the border. It did not engulf our lives the way World War II corroded Germany or Russia. War is a trauma few nibble at in India. When our leaders talk even of surgical strikes, one is not quite sure whether they know the difference between Haldighati or modern war. They seem like actors enacting an outdated play. In fact, one wonders whether India as a society has thought through the idea of war. We talk of war as if it is a problem of traffic control. Our strategists, our international relations experts fetishise security and patriotism. The aridity of the idea of security has done more damage to freedom and democracy than any other modern concept. Security as an official concept needs a genocidal count, an accounting of the number of lives and bodies destroyed in pursuing its logic. The tom-tomming of such words in a bandwagon society destroys the power and pluralism of the idea of India as a society and a democracy.

The biggest casualty of such enthusiasm for war is democracy and rational thought. Our leaders know that the minute we create a demonology around Pakistan, we cease to think rationally or creatively about our own behaviour in Kashmir. We can talk with ease about Pakistani belligerency, about militarism in Pakistan, but we refuse to reflect on our own brutality in Kashmir or Manipur. At a time when the Berlin Wall appears like a distant nightmare and Ulster begins appearing normal, should not India as a creative democracy ask, why is there a state of internal war in Kashmir and the Northeast for decades? Why is it we do not have the moral leadership to challenge Pakistan to engage in peace? Why is it that we as a nation think we are a democracy when internal war and majoritarian mobs are eating into the core of our civilisation? Where does India stand in its vision of the civility of internationalism which we articulated through Panchsheel? Because Pakistan behaves as a rogue state, should we abandon the civilisational dream of a Mohandas Gandhi or an Abdul Ghaffar Khan?

Even if we think strategically, we are losers. Strategy today has been appropriated by the machismo of militarism and management. It has become a term without ethics or values. Strategy, unlike tactics, is a long-range term. It summons a value framework in any decent society. Sadly, strategy shows that India is moving into a geopolitical trap where China, which treats Pakistan as a vassal state, is the prime beneficiary of Pulwama. The Chinese as a society and a regime would be content to see an authoritarian India militarised, sans its greatest achievement which is democracy. What I wish to argue is that strategy also belongs to the perspectives of peace, and it is precisely as a democracy and as a peace-loving nation that we should out-think and outflank China. Peace is not an effeminate challenge to the machismo of the national security state as idol but a civilisational response to the easy brutality of the nation state.

Dissent as survival

In debating with our fellow citizens, we have to show through a Gandhian mode that our sense of Swadeshi and Swaraj is no less. Peace has responsibilities which an arid sense of patriotism may not have. Yet we are condemned to conversation, to dialogue, to arguments persuading those who are sceptical about the very integrity of our being. Dissent becomes an act of both survival and creative caring at this moment. One must realise that India as a civilisation has given the world some of its most creative concepts of peace, inspired by Buddha, Nanak, Kabir, Ghaffar Khan and Gandhi. The challenge before peacedom is to use these visions creatively in a world which takes nuclear war and genocide for granted. Here civil society, the ashram and the university must help create that neighbourhood of ideas, the civics that peace demands to go beyond the current imaginaries of the nation state.

Our peace is a testimony and testament to a society that must return to its civilisational values. It is an appeal to the dreams of the satyagrahi and a realisation that peace needs ideas, ideals and experiments to challenge the current hegemony of the nation state. India as a civilisation cannot do otherwise.

This essay is a piece of dissent at a time when dissent may not be welcome. It is an attempt to look at what I call the Pulwama syndrome, after India’s bombing of terrorist camps in Pakistan. There is an air of achievement and competence, a feeling that we have given a fitting reply to Pakistan. Newspapers have in unison supported the government, and citizens, from actors to cricketers, have been content in stating their loyalty, literally issuing certificates to the government. Yet watching all this, I feel a deep sense of unease, a feeling that India is celebrating a moment which needs to be located in a different context.

Peace needs courage