'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Monday, 10 June 2024

Sunday, 3 March 2024

Thursday, 22 February 2024

Thursday, 31 August 2023

Modi-linked Adani family secretly invested in own shares, documents suggest

Hannah Ellis-Petersen in Delhi and Simon Goodley in London in The Guardian

A billionaire Indian family with close ties to the country’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, secretly invested hundreds of millions of dollars into the Indian stock market, buying its own shares, newly disclosed documents suggest.

According to offshore financial records seen by the Guardian, associates of the Adani family may have spent years discreetly acquiring stock in the Adani Group’s own companies during its meteoric rise to become one of India’s largest and most powerful businesses.

By 2022, its founder, Gautam Adani, had become India’s richest person and the world’s third richest person, worth more than $120bn (£94bn).

In January, a report published by the New York financial research firm Hindenburg accused the Adani Group of pulling off the “largest con in corporate history”.

It alleged there had been “brazen stock manipulation and accounting fraud”, and the use of opaque offshore companies to buy its own shares, contributing to the “sky high” market valuation of the conglomerate, which hit a peak of $288bn in 2022.

The Adani Group denied the Hindenburg claims, which initially wiped $100bn off the conglomerate’s market value and cost Gautam Adani his prime spot on the world rich list.

At the time, the group called the research a “calculated attack on India” and on “the independence, integrity and quality of Indian institutions”.

Yet new documents obtained by the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), and shared with the Guardian and the Financial Times, reveal for the first time the details of an undisclosed and complex offshore operation in Mauritius – seemingly controlled by Adani associates – that was allegedly used to support the share prices of its group of companies from 2013 to 2018.

Up until now, this offshore network had remained impenetrable.

The records also appear to provide compelling evidence of the influential role allegedly played by Adani’s older brother, Vinod, in the secretive offshore operations. The Adani Group says Vinod Adani has “no role in the day to day affairs” of the company.

In the documents, two of Vinod Adani’s close associates are named as sole beneficiaries of offshore companies through which the money appeared to flow. In addition, financial records and interviews suggest investments into Adani stock from two Mauritius-based funds were overseen by a Dubai-based company, run by a known employee of Vinod Adani.

The disclosure could have significant political implications for Modi, whose relationship with Gautam Adani goes back 20 years.

Since the Hindenburg report was published, Modi has faced difficult questions about the nature of his partnership with Gautam Adani and allegations of preferential treatment of the Adani Group by his government.

According to a letter uncovered by the OCCRP and seen by the Guardian, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) had been handed evidence in early 2014 of alleged suspicious stock market activity by the Adani Group – but after Modi was elected months later, the government regulator’s interest seemed to lapse.

In response to fresh questions relating to the new documents, the Adani Group said: “Contrary to your claim of new evidence/proofs, these are nothing, but a rehash of unsubstantiated allegations levelled in the Hindenburg report. Our response to the Hindenburg report is available on our website. Suffice it to state that there is neither any truth to nor any basis for making any of the said allegations against the Adani Group and its promoters and we expressly reject all of them.”

The offshore money trail

The trove of documents lays out a complex web of companies that date back to 2010, when two Adani family associates, Chang Chung-Ling and Nasser Ali Shaban Ahli, began setting up offshore shell companies in Mauritius, the British Virgin Islands and the United Arab Emirates.

These financial records appear to show that four of the offshore companies established by Chang and Ahli – who have both been directors of Adani-linked companies – sent hundreds of millions of dollars into a large investment fund in Bermuda called Global Opportunities Fund (GOF), with those monies invested in the Indian stock market from 2013 onwards.

This investment was made by introducing yet another layer of opacity. Financial records paint a picture of money from the pair’s offshore companies flowing from GOF into two funds to which GOF subscribed: Emerging India Focus Funds (EIFF) and EM Resurgent Fund (EMRF).

These funds then appear to have spent years acquiring shares in four Adani-listed companies: Adani Enterprises, Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone, Adani Power and, later, Adani Transmission. The records shine a light on how money in opaque offshore structures can flow secretly into the shares of publicly listed companies in India.

The investment decisions of these two funds appeared to be made under the guidance of an investment advisory company controlled by a known employee and associate of Vinod Adani, based in Dubai.

In May 2014, EIFF appears to have held more than $190m of shares in three Adani entities, while EMRF looks to have invested around two-thirds of its portfolio in about $70m of Adani stock. Both funds appear to have used money that came solely from the companies controlled by Chang and Ahli.

In September 2014, a separate set of financial records set out how the four Chang and Ahli offshore companies had invested about $260m in Adani shares via this structure.

Documents show that this investment appeared to grow over the next three years: by March 2017, the Chang and Ahli offshore companies had invested $430m – 100% of their total portfolio – into Adani company stock.

When contacted by the Guardian by phone, Chang declined to discuss the documents setting out his company’s investments in Adani shares. Nor would he answer questions about his links to Vinod Adani, who along with Ahli did not respond to efforts to contact them.

Indian stock market rules

The alleged offshore enterprise of the Adani associates raises questions about the possible breaching of Indian market rules that prevent stock manipulation and regulate public shareholdings of companies.

The rules state that 25% of a company’s shares must be kept “free float” – meaning they are available for public trade on the stock exchange – while 75% can be held by promoters, who have declared their direct involvement or connection with the company. Vinod Adani has recently been acknowledged by the conglomerate as a promoter.

However, records show that at the peak of their investment, Ahli and Chang held between 8% and 13.5% of the free floating shares of four Adani companies through EIFF and EMRF. If their holdings were classified as being controlled by Vinod Adani proxies, the Adani Group’s promoter holdings would have seemingly breached the 75% limit.

Political ties

Gautam Adani has long been accused of benefiting from his powerful political connections. His relationship with Modi dates back to 2002, when he was a businessman in Gujarat and Modi was chief minister of the state, and their rise has appeared to happen in tandem since. After Modi won the general election in May 2014, he flew to Delhi on Gautam Adani’s plane, a scene captured in a now well-known photo of him in front of the Adani corporate logo.

During Modi’s time as leader, the power and influence of the Adani Group has soared, with the conglomerate acquiring lucrative state contracts for ports, power plants, electricity, coalmines, highways, energy parks, slum redevelopment and airports. In some cases, laws were amended that allowed Adani Group companies to expand in sectors such as airports and coal. In turn, the stock value of the Adani Group rose from about $8bn in 2013 to $288bn by September 2022.

Adani has repeatedly denied that his longstanding connection with the prime minister has led to preferential treatment, as has the Indian government.

Yet a document unearthed by the OCCRP and seen by the Guardian suggests the SEBI, the government regulator now in charge of investigating the Adani Group, was made aware of stock market activity using Adani offshore funds as far back as early 2014.

In a letter dated January 2014, Najib Shah, the then head of the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence (DRI), India’s financial law enforcement agency, wrote to Upendra Kumar Sinha, the then head of the SEBI.

“There are indications that [Adani-linked] money may have found its way to stock markets in India as investment and disinvestment in the Adani Group,” Shah said in the letter.

He noted that he had sent this material to Sinha because the SEBI was “understood to be investigating into the dealings of the Adani Group of companies in the stock market”.

However, a few months later, after Modi was elected in May 2014, the SEBI’s apparent interest seemed to disappear, a source working for the regulator at the time said.

The SEBI has never publicly disclosed the warning given by the DRI, nor any investigation it might have conducted into the Adani Group in 2014. The letter appears to misalign with statements made by the SEBI in recent court filings in which it denied there were investigations into the Adani Group before 2020, as well as saying suggestions it had investigated the Adani Group dating back to 2016 were “factually baseless”.

The ability of the SEBI, a regulator under the purview of the Modi government, to independently investigate the Adani Group has recently been called into question by critics, lawyers and the political opposition.

According to a report given in May to the supreme court – which set up an expert committee to investigate the Adani Group after the publication of the Hindenburg report – the SEBI had been investigating 13 offshore investors in the conglomerate since 2020 but had “hit a wall” in trying to establish if they were linked to the Adani Group. Two of the entities under investigation are EIFF and EMRF.

The regulator has been accused of dragging its feet in their investigation into possible violations by the Adani Group, seeking several extensions. On Friday, the SEBI submitted a report to the supreme court stating that their investigations were in the final stages but did not reveal any findings.

The Adani Group said: “The provocative nature of the story and the proposed timing of its publication, when the allegations in it are entirely based on matters which are already under a formal investigation by SEBI and is at the verge of finalisation of the report and while the honourable supreme court hearing is also scheduled shortly; makes us believe that the proposed publication is being done wilfully to defame, disparage, erode value of and cause loss to the Adani Group and its stakeholders.

“Further, it is categorically stated that all the Adani Group’s publicly listed entities are in compliance with all applicable laws, including the regulation relating to public share holdings and PMLA [Prevention of Money Laundering Act].”

A spokesperson for the two funds that invested in Adani stocks – EIFF and EMRF – said the funds had not been “involved in any wrongdoing generally and particularly in connection with the Adani Group”.

It added: “Both the funds had multiple investments across asset classes like equities, mutual funds, alternate investment funds, bonds etc. Amongst these, EIFF and EMRF had investment in equities of the Adani Group, apart from other investments. EIFF and EMRF received subscriptions from Global Opportunities Fund Limited (GOF) which was a broad-based fund as per declarations received. GOF fully redeemed all its participation in EIFF in March 2019 and EMRF in March 2020.”

The SEBI did not respond to requests for comment.

Saturday, 30 January 2021

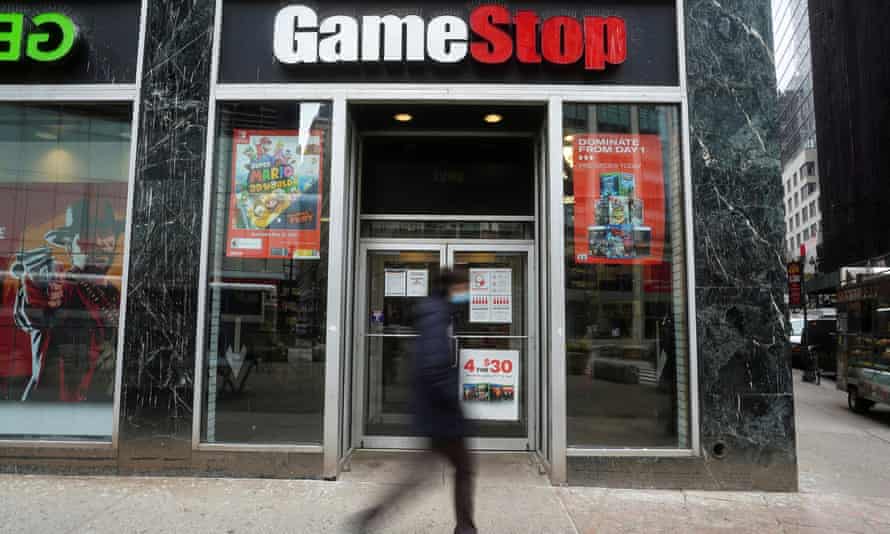

The GameStop affair is like tulip mania on steroids

Towards the end of 1636, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in the Netherlands. The concept of a lockdown was not really established at the time, but merchant trade slowed to a trickle. Idle young men in the town of Haarlem gathered in taverns, and looked for amusement in one of the few commodities still trading – contracts for the delivery of flower bulbs the following spring. What ensued is often regarded as the first financial bubble in recorded history – the “tulip mania”.

Nearly 400 years later, something similar has happened in the US stock market. This week, the share price of a company called GameStop – an unexceptional retailer that appears to have been surprised and confused by the whole episode – became the battleground between some of the biggest names in finance and a few hundred bored (mostly) bros exchanging messages on the WallStreetBets forum, part of the sprawling discussion site Reddit.

The rubble is still bouncing in this particular episode, but the broad shape of what’s happened is not unfamiliar. Reasoning that a business model based on selling video game DVDs through shopping malls might not have very bright prospects, several of New York’s finest hedge funds bet against GameStop’s share price. The Reddit crowd appears to have decided that this was unfair and that they should fight back on behalf of gamers. They took the opposite side of the trade and pushed the price up, using derivatives and brokerage credit in surprisingly sophisticated ways to maximise their firepower.

To everyone’s surprise, the crowd won; the hedge funds’ risk management processes kicked in, and they were forced to buy back their negative positions, pushing the price even higher. But the stock exchanges have always frowned on this sort of concerted action, and on the use of leverage to manipulate the market. The sheer volume of orders had also grown well beyond the capacity of the small, fee-free brokerages favoured by the WallStreetBets crowd. Credit lines were pulled, accounts were frozen and the retail crowd were forced to sell; yesterday the price gave back a large proportion of its gains.

To people who know a lot about stock exchange regulation and securities settlement, this outcome was quite inevitable – it’s part of the reason why things like this don’t happen every day. To a lot of American Redditors, though, it was a surprising introduction to the complexity of financial markets, taking place in circumstances almost perfectly designed to convince them that the system is rigged for the benefit of big money.

Corners, bear raids and squeezes, in the industry jargon, have been around for as long as stock markets – in fact, as British hedge fund legend Paul Marshall points out in his book Ten and a Half Lessons From Experience something very similar happened last year at the start of the coronavirus lockdown, centred on a suddenly unemployed sports bookmaker called Dave Portnoy. But the GameStop affair exhibits some surprising new features.

Most importantly, it was a largely self-organising phenomenon. For most of stock market history, orchestrating a pool of people to manipulate markets has been something only the most skilful could achieve. Some of the finest buildings in New York were erected on the proceeds of this rare talent, before it was made illegal. The idea that such a pool could coalesce so quickly and without any obvious sign of a single controlling mind is brand new and ought to worry us a bit.

And although some of the claims made by contributors to WallStreetBets that they represent the masses aren’t very convincing – although small by hedge fund standards, many of them appear to have five-figure sums to invest – it’s unfamiliar to say the least to see a pool motivated by rage or other emotions as opposed to the straightforward desire to make money. Just as air traffic regulation is based on the assumption that the planes are trying not to crash into one another, financial regulation is based on the assumption that people are trying to make money for themselves, not to destroy it for other people.

When I think about market regulation, I’m always reminded of a saying of Édouard Herriot, the former mayor of Lyon. He said that local government was like an andouillette sausage; it had to stink a little bit of shit, but not too much. Financial markets aren’t video games, they aren’t democratic and small investors aren’t the backbone of capitalism. They’re nasty places with extremely complicated rules, which only work to the extent that the people involved in them trust one another. Speculation is genuinely necessary on a stock market – without it, you could be waiting days for someone to take up your offer when you wanted to buy or sell shares. But it’s a necessary evil, and it needs to be limited. It’s a shame that the Redditors found this out the hard way.

Wednesday, 13 March 2019

How wealthy Americans ‘get their kids into university'

William McGlashan had to make his son a football player. And quickly.

In exchange for a $250,000 payment, a California-based university-admissions consultant had arranged for the younger McGlashan to skirt the normal application process at the University of Southern California and be accepted as a prized American football recruit. A “side door” into the university, the consultant, William Singer, called it.

The problem was that the boy did not play football. They did not even have a football team at his secondary school. “We have images of him in lacrosse. I don’t know if that matters,” offered Mr McGlashan, a top executive at the private equity firm TPG and co-founder with rock star Bono of the Rise Fund, a socially conscious investment vehicle.

“They [USC] don’t have a lacrosse team,” Mr Singer responded. Then he took matters into his own hands. “I’m going to make him a kicker/punter,” he decided, listing specialist positions in the sport often occupied by the slight of frame. “I’ll get a picture and figure out how to Photoshop and stuff.”

“He does have really strong legs,” Mr McGlashan joked.

The two men bantered about the deal, and how Mr Singer had made other applicants appear to be champion water polo players for the same purpose. Months earlier, the 55-year-old Mr McGlashan had paid Mr Singer $50,000 to have someone doctor his son’s university entrance exam. “Pretty funny. The way the world works these days is unbelievable,” Mr McGlashan observed.

"I can do anything and everything, if you guys are amenable to doing it" William Singer, founder of The Edge College & Career Network

Those discussions are reproduced in a criminal complaint filed by the Justice Department on Tuesday after an investigation into bribery in college admissions that resulted in charges against 50 individuals — including prominent actors and investors — and involved some of the most prestigious names in US higher education.

At the centre of the scheme was Mr Singer, 58, who was fired in 1988 as a high school basketball coach in Sacramento because of his abusive behaviour toward referees. He later reinvented himself as a svengali in Newport Beach for his apparent mastery of the increasingly cut-throat university admissions game. On Tuesday Mr Singer pleaded guilty to federal charges including racketeering conspiracy and obstruction of justice.

“OK, so, who we are — what we do is help the wealthiest families in the US get their kids into school,” Mr Singer told one prospective client, Gordon Caplan, the co-chairman of the prominent US law firm Willkie Farr & Gallagher.

In extensive phone conversations authorities recorded with 32 parents, Mr Singer comes off as an indispensable problem-solver and quasi-magician — a man able to spare one client, the actress of Lori Loughlin, the apparent indignity of having to send her daughter to Arizona State University.

“I can make [test] scores happen, and nobody on the planet can get scores to happen,” he boasted to one client of his consultancy, The Edge College & Career Network.

“She won’t even know that it happened. It will happen as though, she will think that she’s really super smart, and she got lucky on a test, and you got a score now. There’s lots of ways to do this. I can do anything and everything, if you guys are amenable to doing it.”

All told, Mr Singer collected about $25m in bribes over a seven-year period, according to authorities.

US college admissions are supposed to be a merit-based business. But it has always had its set-aside places for legacy applicants and the children of those willing to fork over enough money.

At a time when the affordability of university education is emerging as a major political issue, the revelation that the moneyed elites had gamed the system for their children — at the expense of more deserving candidates — is likely to be seized on by politicians.

Daniel Golden won a Pulitzer Prize for his book, The Price of Admission, which detailed the underside of the business at a time when globalisation was raising the value of a prestigious university degree — and making it evermore competitive for students to access them.

Writing for The Guardian newspaper in 2016, Mr Golden called it the “grubby secret of American higher education: that the rich buy their underachieving children’s way into elite universities with massive, tax-deductible donations”.

He claimed that President Donald Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner — not regarded as a brilliant scholar in high school — was accepted by Harvard not long after his father Charles made a $2.5m donation to the university.

Mr Singer called that “the backdoor”. At The Edge, he came up with a “side door”: arranging bribes for tennis, sailing and soccer coaches so that they would sneak his applicants into school as ostensible sports stars.

As the criminal complaint noted, many of the schools reserve admissions spaces for their athletics department: “At Georgetown, approximately 158 admissions slots are allocated to athletic coaches, and students recruited for those slots have substantially higher admissions prospects than non-recruited students.”

USC, a school that was once considered more expensive than selective, was one of Mr Singer’s best bets. With the alleged connivance of the school’s senior women’s athletic director, Donna Heinel, he wangled spots for applicants supposedly destined for its water polo, basketball, football and rowing teams. Ms Heinel and the water polo coach, Jovan Vavic, were dismissed by the school on Tuesday and also criminally charged.

Running through the complaint is the angst of affluent parents caught up in a school admissions process that is increasingly viewed as a make-or-break gateway to future success.

One of those charged, Agustin Huneeus, a California vineyard owner, appears tormented that his daughter is losing out to Mr McGlashan’s son, a schoolmate.

“Is Bill [McGlashan] doing any of this shit? Is he just talking a clean game with me and helping his kid or not? Cause he makes me feel guilty.”

Mr Huneeus paid $50,000 for someone to doctor his daughter’s college entrance exam. She ended up scoring in the 96th percentile.

Like Mr McGlashan, Mr Huneeus also opted to pay Mr Singer $250,000 to buy her admission to USC — in this case as a star water polo player. The girl was late in sending a picture so Mr Singer found one of an actual water polo player and submitted that instead.

On one occasion Mr Singer had two different clients unwittingly sitting fraudulent entrance exams in the same testing room. In order for the scheme to work, he repeatedly emphasised to parents it was essential that they petitioned for medical exemptions so that their children could be given extra time to complete the test — ideally a few days. That way proctors bribed by Mr Singer would have occasion to adjust the results.

“What happened is, all the wealthy families that figured out that if I get my kid tested and they get extended time, they can do better on the test. So most of these kids don’t even have issues, but they’re getting time. The playing field is not fair,” Mr Singer explains to Mr Caplan, the lawyer, as he markets his services.

“No, it’s not. I mean this is, to be honest, it feels a little weird. But,” Mr Caplan responds.

Ultimately, one thing that Mr Caplan and the parents shared was a determination to keep the scheme secret from the children they were desperate to help. It was no easy feat since, in some cases, test scores would be massively inflated for mediocre — even poor — students.

There was also the need to secure the medical waivers and then petition for the students to take the test at specific facilities in Houston or Hollywood controlled by Mr Singer. (He often advised parents to tell authorities their students had to travel on the appointed date for a wedding or bar mitzvah.)

“Now does he, here’s the only question, does he know? Is there a way that he doesn’t know what happened?” Mr McGlashan asked of his son at one point.

Mr McGlashan — who was placed on “indefinite administrative leave” by TPG on Tuesday and did not respond to requests for comment — seemingly managed to put aside his reservations.

So did another parent, Marci Palatella, the chief executive of a California liquor distributor. She and her spouse paid Mr Singer $500,000 to secure their son’s admission to USC after apparently hearing about his services from “people at Goldman Sachs who have, you know, recommended you highly”.

As Ms Palatella later confided to Mr Singer, she and her partner “laugh every day” about the scheme. “We’re like, ‘It was worth every cent.’”

FBI affidavit: overview of the conspiracy

Parents paid about $25m in bribes between 2011 and 2018.

Colleges and universities involved included Yale University, Stanford University, the University of Texas, the University of Southern California, and the University of California Los Angeles, Georgetown and Wake Forest

Bribes to college entrance exam administrators allowed a third party to assist in cheating on college entrance exams, in some cases posing as the actual students, and in others by providing students with answers during the exams or by correcting their answers after they had completed the exams

Bribes to university athletic coaches and administrators to designate students as purported athletic recruits regardless of their athletic abilities, and, in some cases, even though they did not play the sport they were purportedly recruited to play

Having a third party take classes in place of the actual students, with the understanding that grades earned in those classes would be submitted as part of the student’s college applications

Submitting falsified applications for admission to universities that included the fraudulently obtained exam scores and class grades, and often listed fake awards and athletic activities

Disguising the nature and source of the bribe payments by funnelling the money through the accounts of a purported, tax-deductible, charity, The Key Worldwide Foundation, from which many of the bribes were then paid