'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label results. Show all posts

Showing posts with label results. Show all posts

Monday, 10 June 2024

Tuesday, 14 April 2020

Will GCSE and A-level students get a fair deal when coronavirus has cancelled exams?

Candidates have missed out on Easter revision but, say assessment experts, a new system could trump exams writes Liz Lightfoot in The Guardian

In any normal year, a sixth-form teacher would be pleased to be handed three four-page, well-researched essays by an exam candidate. But as schools broke up for Easter, one head of history in Kent had to tell his conscientious student she was too late.

Only work submitted before 20 March – the date schools closed because of the coronavirus, with this year’s public examinations cancelled – can be counted towards students’ final grades. Even practical coursework for arts subjects cannot be completed.

“She was upset because she had not done any timed essays in the year that were long and precise enough. She thought she would get 60 and not the 75 she needed for an A*,” he said.

“But the rule is fair because some students have much better resources to work at home than others, and there would be too much scope for cheating,” added the teacher, who has been told by his senior leadership team not to comment publicly on plans to grade students.

Teachers tell of students in tears because the cancellation of exams means they have lost the chance to raise their grades with Easter revision.

Fortunately, say assessment experts, students need not be downhearted. They say this year’s results will be based on teachers’ recommendations, called “centre assessment grades”, plus statistical moderation by examiners, who can change the grades up or down. This combination, they say, is likely to be fairer than the usual exam system.

“This done well by teachers with integrity is the fairest method, and beats the reliability of the current exam system hands down,” says Dennis Sherwood, who monitors assessment systems and has worked as a consultant at Ofqual, the exams regulator.

A better exam system may be a welcome legacy of the coronavirus pandemic, he believes. “If we can demonstrate that teacher assessment works, is trusted, and can be done a lot more quickly and be less costly with a lot less emotional wear and tear for students, we are in a much better position in coming years to evolve something better than the present system.”

He says Ofqual’s own research, published in November 2018, shows that about 200,000 – a quarter – of A-level grades would be changed if the scripts were re-marked by a senior examiner. For GCSEs, 1.3m grades did not match, again one in four.

While it may shock the public to realise just how unreliable grades can be, it is no surprise to most teachers. “I am aware every year, particularly with my subject, psychology, that the outcomes vary to a degree I have never been able to predict,” says the head of social sciences at a large academy school in the south of England.

“Exams themselves do not provide a highly reliable outcome. Nor are results over the years necessarily stable. One year we had 80% A or A* for A-level, and the next year it went down to 20%. It comes down to the luck of which questions come up on the paper and how the scripts are graded.

“For a lot of us, grades are linked to our sense of wellbeing and efficacy. Ten years ago I felt they were my grades as well, but I don’t feel that any more, I have learned to accept that I cannot control the outcomes. All I can do is teach as well as I can.

“The problem is that this year I have been asked to put in the grades myself. I’ve been talking to other people in the same boat and we don’t like it, because our job is to be alongside the student, helping them to do as well as possible,” he says.

Usually exam papers are marked by examiners and then, once the overall picture emerges, the different exam boards decide the number of marks needed for each subject grade. They work out how many candidates will get each grade and submit the estimates to Ofqual. The regulator then collates the data from all the boards to check that the proportion of, say, A grades awarded nationally is in line with previous years and fits with the information it holds about the prior attainment of the cohort.

This year teachers will recommend what grades students should be awarded and put students in rank order within the grades – the ones most likely to achieve that grade at the top, and the weakest near the grade boundary at the bottom. To deliver the fairest outcomes, Sherwood suggests students should be ranked first, and then the grade boundaries determined to reflect the school’s previous results in the qualification.

Ofqual tells teachers they should take a student’s prior performance over the course into account, but suggests results in previous examinations should be used “at centre level” to judge the ability of the class and year group, not the individual candidate. In other words, an A-level student should not be marked down for their GCSE results.

A student working at an A grade during the year and hoping to raise it to an A* by the exam date, may still get the coveted top grade if the school got five A* grades last year and thinks he or she is one of their top five students.

Teachers have been told not to tell students what grades they are submitting, because they may not be the final ones. It could leave teachers open to bribery, abuse or even legal action. Ofqual has yet to announce how students will be able to appeal grades they feel are unfair.

A head of English, who wants to remain anonymous, says his department will not be relying much on teacher opinions, but on aggregated data showing how well the candidates performed in mocks, tests and assignments compared to each other.

“Results are capped by the proportion of grades awarded in previous years, so if you got five A*s last year, that’s what Ofqual will expect to see. It means that you have to be very careful, if you move someone up on a hunch they would have done better in the actual examination, you are moving someone else down,” he says.

Teachers also should be aware that research has consistently demonstrated unconscious teacher bias against some groups based on race, class, gender and even personal qualities such as attractiveness, he explains.

There will be anomalies for some schools. Putney High, an independent school in London, for example, last year added Fashion and Textiles to its art and textile A-levels; only six girls chose it, with half getting an A* grade and half a B, making an A grade average. This year, with numbers doubling, the school expects two-thirds to get an A* and one third an A.

“This year’s is a very strong cohort and they deserve the grades but will the exam board look at last year’s results, think we have been too generous, and put their grades down? That would be very unfair,” says Stuart McLaughlin, the school’s head of textiles.

Fast-improving schools could also miss out if their grades are mapped to those awarded before, as could those where the intake changes, such as a boys’ school admitting girls to the sixth form. But a spokesman for Ofqual said it was still consulting on its model of “standardisation” that could take such circumstances into account.

In any normal year, a sixth-form teacher would be pleased to be handed three four-page, well-researched essays by an exam candidate. But as schools broke up for Easter, one head of history in Kent had to tell his conscientious student she was too late.

Only work submitted before 20 March – the date schools closed because of the coronavirus, with this year’s public examinations cancelled – can be counted towards students’ final grades. Even practical coursework for arts subjects cannot be completed.

“She was upset because she had not done any timed essays in the year that were long and precise enough. She thought she would get 60 and not the 75 she needed for an A*,” he said.

“But the rule is fair because some students have much better resources to work at home than others, and there would be too much scope for cheating,” added the teacher, who has been told by his senior leadership team not to comment publicly on plans to grade students.

Teachers tell of students in tears because the cancellation of exams means they have lost the chance to raise their grades with Easter revision.

Fortunately, say assessment experts, students need not be downhearted. They say this year’s results will be based on teachers’ recommendations, called “centre assessment grades”, plus statistical moderation by examiners, who can change the grades up or down. This combination, they say, is likely to be fairer than the usual exam system.

“This done well by teachers with integrity is the fairest method, and beats the reliability of the current exam system hands down,” says Dennis Sherwood, who monitors assessment systems and has worked as a consultant at Ofqual, the exams regulator.

A better exam system may be a welcome legacy of the coronavirus pandemic, he believes. “If we can demonstrate that teacher assessment works, is trusted, and can be done a lot more quickly and be less costly with a lot less emotional wear and tear for students, we are in a much better position in coming years to evolve something better than the present system.”

He says Ofqual’s own research, published in November 2018, shows that about 200,000 – a quarter – of A-level grades would be changed if the scripts were re-marked by a senior examiner. For GCSEs, 1.3m grades did not match, again one in four.

While it may shock the public to realise just how unreliable grades can be, it is no surprise to most teachers. “I am aware every year, particularly with my subject, psychology, that the outcomes vary to a degree I have never been able to predict,” says the head of social sciences at a large academy school in the south of England.

“Exams themselves do not provide a highly reliable outcome. Nor are results over the years necessarily stable. One year we had 80% A or A* for A-level, and the next year it went down to 20%. It comes down to the luck of which questions come up on the paper and how the scripts are graded.

“For a lot of us, grades are linked to our sense of wellbeing and efficacy. Ten years ago I felt they were my grades as well, but I don’t feel that any more, I have learned to accept that I cannot control the outcomes. All I can do is teach as well as I can.

“The problem is that this year I have been asked to put in the grades myself. I’ve been talking to other people in the same boat and we don’t like it, because our job is to be alongside the student, helping them to do as well as possible,” he says.

Usually exam papers are marked by examiners and then, once the overall picture emerges, the different exam boards decide the number of marks needed for each subject grade. They work out how many candidates will get each grade and submit the estimates to Ofqual. The regulator then collates the data from all the boards to check that the proportion of, say, A grades awarded nationally is in line with previous years and fits with the information it holds about the prior attainment of the cohort.

This year teachers will recommend what grades students should be awarded and put students in rank order within the grades – the ones most likely to achieve that grade at the top, and the weakest near the grade boundary at the bottom. To deliver the fairest outcomes, Sherwood suggests students should be ranked first, and then the grade boundaries determined to reflect the school’s previous results in the qualification.

Ofqual tells teachers they should take a student’s prior performance over the course into account, but suggests results in previous examinations should be used “at centre level” to judge the ability of the class and year group, not the individual candidate. In other words, an A-level student should not be marked down for their GCSE results.

A student working at an A grade during the year and hoping to raise it to an A* by the exam date, may still get the coveted top grade if the school got five A* grades last year and thinks he or she is one of their top five students.

Teachers have been told not to tell students what grades they are submitting, because they may not be the final ones. It could leave teachers open to bribery, abuse or even legal action. Ofqual has yet to announce how students will be able to appeal grades they feel are unfair.

A head of English, who wants to remain anonymous, says his department will not be relying much on teacher opinions, but on aggregated data showing how well the candidates performed in mocks, tests and assignments compared to each other.

“Results are capped by the proportion of grades awarded in previous years, so if you got five A*s last year, that’s what Ofqual will expect to see. It means that you have to be very careful, if you move someone up on a hunch they would have done better in the actual examination, you are moving someone else down,” he says.

Teachers also should be aware that research has consistently demonstrated unconscious teacher bias against some groups based on race, class, gender and even personal qualities such as attractiveness, he explains.

There will be anomalies for some schools. Putney High, an independent school in London, for example, last year added Fashion and Textiles to its art and textile A-levels; only six girls chose it, with half getting an A* grade and half a B, making an A grade average. This year, with numbers doubling, the school expects two-thirds to get an A* and one third an A.

“This year’s is a very strong cohort and they deserve the grades but will the exam board look at last year’s results, think we have been too generous, and put their grades down? That would be very unfair,” says Stuart McLaughlin, the school’s head of textiles.

Fast-improving schools could also miss out if their grades are mapped to those awarded before, as could those where the intake changes, such as a boys’ school admitting girls to the sixth form. But a spokesman for Ofqual said it was still consulting on its model of “standardisation” that could take such circumstances into account.

Thursday, 4 February 2016

Teachers increasingly boosting predicted A-level grades to help pupils win top university places

Richard Garner in The Independent

Increasing numbers of teachers are boosting their pupils’ predicted A-level grades to help them secure offers of places at Britain’s top universities – which in turn are accepting more students who miss their targets, largely to increase their income.

Figures from Ucas, the university admissions body, show that 63 per cent of all candidates are now predicted to get at least an A and two B grades at A level – up 9 percentage points from four years ago.

Yet the data shows that only a fifth of those predicted to score ABB actually achieve those grades – a 40 per cent drop from just six years ago.

READ MORE

Students increasingly admitted to university without three A-levels

The ploy by teachers has been successful because growing numbers of universities are offering “discounts” on their conditional offers to prospective students when A-level results are released.

This is because the Government decision to lift the cap on the number of places universities can offer has increased competition among the institutions when it comes to signing up students.

However, many teachers still reckon they need to bump up their students’ potential A-level grades to ensure they are noticed and are given a provisional offer by universities. More than half of pupils accepted on predicted A-level results – 52 per cent – missed their conditional offer grades by one grade or two, another substantial rise on four years ago. Senior academics say controversy over the issue could reignite calls to move to a system whereby pupils apply for their university places after they receive their A-level results.

Many teachers believe they need to bump up their students’ potential A-level grades to ensure they receive offers by universities (iStock)

The new figures and the trend they highlight were disclosed by Mary Curnock Cook, chief executive of Ucas, at a conference at Wellington College on the future of higher education.

University admissions in numbers

63% of all candidates predicted to get at least an A and two B grades at A-levels

One in five actually achieve those grades

495,940 university applicants in England

52% of candidates accepted on predicted grades miss them by one grade or two

44% of students being admitted with three B grade passes or lower, compared with 20 per cent in 2011

Ms Curnock Cook said that, in discussions with teachers, she had asked: “Surely you wouldn’t be over-predicting your students’ grades last summer?” She told the conference: “I have teachers coming back to me saying: ‘Actually, yes we would.’

“The offers are being discounted at confirmation time,” said Ms Curnock Cook, referring to A-level results day. “It’s been [caused by] the lifting of the number controls that has increased competition [amongst universities].”

“You have to hope you can unlock some latent talent [in those taken in with lower grades],” said one university source. “If you don’t take them in, they could be snapped up by a rival and their reputation increases.”

As well as lower-ranking institutions, high-tariff universities – those most selective in their intake – are also lowering their entry requirements, with 44 per cent of students being admitted with three B-grade passes or lower, compared with just 20 per cent in 2011.

Professor Michael Arthur, provost of University College London, said his university had dropped a grade in 9 per cent of admissions.

Many universities have seen huge rises in the numbers of students they are enrolling. Professor Arthur said the number of students at his university had soared from 24,000 six years ago to 37,500. Part of the increase was down to mergers with other bodies such as the Institute of Education – but at least half was due to a rise in student numbers.

The UCAS clearing house call centre in Cheltenham (Getty Images)

Another teacher said that performance-related pay, which means teachers’ salary increases depend on the results of their pupils – was leading them to predict higher grades.

“Performance-related pay and performance-related management play a part,” they said. “It is why you have to be a little bit aspirational.”

However, it was acknowledged this could be a double-edged sword – as failure to achieve the grades could result in teachers being penalised for failing to meet their targets.

Ms Curnock Cook also predicted that the number of students taking the A-level route to university would continue to drop over the next four years,

Last week Ucas showed that the number of students taking the vocational route through Btecs had almost doubled from 14 per cent in 2008 to 26 per cent last year. Predicted outcomes showed the number taking the traditional A-level route was likely to decline by 25,000 by 2020 – while the number with vocational qualifications would go up by 15,000.

A Department for Education spokesperson said: "We trust teachers to act in the best interests of their students by giving fair predicted A level grades that accurately reflect their ability.

"Distorting grades would be unfair on the pupils involved and could result in universities having to artificially inflate their entrance requirements, rendering it pointless in the long run."

Increasing numbers of teachers are boosting their pupils’ predicted A-level grades to help them secure offers of places at Britain’s top universities – which in turn are accepting more students who miss their targets, largely to increase their income.

Figures from Ucas, the university admissions body, show that 63 per cent of all candidates are now predicted to get at least an A and two B grades at A level – up 9 percentage points from four years ago.

Yet the data shows that only a fifth of those predicted to score ABB actually achieve those grades – a 40 per cent drop from just six years ago.

READ MORE

Students increasingly admitted to university without three A-levels

The ploy by teachers has been successful because growing numbers of universities are offering “discounts” on their conditional offers to prospective students when A-level results are released.

This is because the Government decision to lift the cap on the number of places universities can offer has increased competition among the institutions when it comes to signing up students.

However, many teachers still reckon they need to bump up their students’ potential A-level grades to ensure they are noticed and are given a provisional offer by universities. More than half of pupils accepted on predicted A-level results – 52 per cent – missed their conditional offer grades by one grade or two, another substantial rise on four years ago. Senior academics say controversy over the issue could reignite calls to move to a system whereby pupils apply for their university places after they receive their A-level results.

Many teachers believe they need to bump up their students’ potential A-level grades to ensure they receive offers by universities (iStock)

The change was called for by a government inquiry headed by former Vice-Chancellor Steven Schwartz a decade ago but disappeared from the table when universities and schools could not agree to the changes necessary to the education calendar to implement it.

The new figures and the trend they highlight were disclosed by Mary Curnock Cook, chief executive of Ucas, at a conference at Wellington College on the future of higher education.

University admissions in numbers

63% of all candidates predicted to get at least an A and two B grades at A-levels

One in five actually achieve those grades

495,940 university applicants in England

52% of candidates accepted on predicted grades miss them by one grade or two

44% of students being admitted with three B grade passes or lower, compared with 20 per cent in 2011

Ms Curnock Cook said that, in discussions with teachers, she had asked: “Surely you wouldn’t be over-predicting your students’ grades last summer?” She told the conference: “I have teachers coming back to me saying: ‘Actually, yes we would.’

“The offers are being discounted at confirmation time,” said Ms Curnock Cook, referring to A-level results day. “It’s been [caused by] the lifting of the number controls that has increased competition [amongst universities].”

“You have to hope you can unlock some latent talent [in those taken in with lower grades],” said one university source. “If you don’t take them in, they could be snapped up by a rival and their reputation increases.”

As well as lower-ranking institutions, high-tariff universities – those most selective in their intake – are also lowering their entry requirements, with 44 per cent of students being admitted with three B-grade passes or lower, compared with just 20 per cent in 2011.

Professor Michael Arthur, provost of University College London, said his university had dropped a grade in 9 per cent of admissions.

Many universities have seen huge rises in the numbers of students they are enrolling. Professor Arthur said the number of students at his university had soared from 24,000 six years ago to 37,500. Part of the increase was down to mergers with other bodies such as the Institute of Education – but at least half was due to a rise in student numbers.

However, the number of university applicants from England decreased on the previous year by 0.2 percentage points to 495,940, the new figures show. The number of 18-year-olds applying also fell by 2.2 per cent.

Overall the number of university applicants for this autumn has held steady – with 593,720 applicants (up 0.2 percentage points on last year) by the time of the January deadline. But the increase was down to a significant rise in applications from the EU – up 6 percentage points to 45,220.

The figures show that more disadvantaged pupils applied than ever before – up 5 percentage points in England, 2 in Scotland and 8 in Wales.

Ms Curnock Cook urged students to be “bold” in their Ucas applications and take advantage of the fact that leading universities were lowering their admissions criteria. Speakers at the conference said parental pressure was partly to blame for teachers upping predictions for their pupils.

Overall the number of university applicants for this autumn has held steady – with 593,720 applicants (up 0.2 percentage points on last year) by the time of the January deadline. But the increase was down to a significant rise in applications from the EU – up 6 percentage points to 45,220.

The figures show that more disadvantaged pupils applied than ever before – up 5 percentage points in England, 2 in Scotland and 8 in Wales.

Ms Curnock Cook urged students to be “bold” in their Ucas applications and take advantage of the fact that leading universities were lowering their admissions criteria. Speakers at the conference said parental pressure was partly to blame for teachers upping predictions for their pupils.

The UCAS clearing house call centre in Cheltenham (Getty Images)

Another teacher said that performance-related pay, which means teachers’ salary increases depend on the results of their pupils – was leading them to predict higher grades.

“Performance-related pay and performance-related management play a part,” they said. “It is why you have to be a little bit aspirational.”

However, it was acknowledged this could be a double-edged sword – as failure to achieve the grades could result in teachers being penalised for failing to meet their targets.

Ms Curnock Cook also predicted that the number of students taking the A-level route to university would continue to drop over the next four years,

Last week Ucas showed that the number of students taking the vocational route through Btecs had almost doubled from 14 per cent in 2008 to 26 per cent last year. Predicted outcomes showed the number taking the traditional A-level route was likely to decline by 25,000 by 2020 – while the number with vocational qualifications would go up by 15,000.

A Department for Education spokesperson said: "We trust teachers to act in the best interests of their students by giving fair predicted A level grades that accurately reflect their ability.

"Distorting grades would be unfair on the pupils involved and could result in universities having to artificially inflate their entrance requirements, rendering it pointless in the long run."

Thursday, 13 August 2015

Your students’ A-level results could easily be wrong

Students may not be getting the exam grades they deserve due to the inconsistent marking. Photograph: Alamy

Anonymous in The Guardian

Thursday 13 August 2015 07.00 BST

Anonymous in The Guardian

Thursday 13 August 2015 07.00 BST

Congratulations. Your students have got their grades, university beckons and you can bask in the warm glow of a job well done. Parents, colleagues and students salute you. But are the results accurate? As a senior examiner with more than 20 years’ experience, let me share my doubts.

Perhaps you picture genteel examiners sitting in Oxbridge common rooms, languidly resting on armchairs as they earnestly discuss whether Chloe’s essay merits an A* or merely an A. Maybe you imagine seasoned professionals kindly donating their holidays to mark in the garden over Earl Grey tea and lemon drizzle cake? Wise up. Examining is a ruthless multi-million pound business. There are two types of examiners: the quick and the dead. The faster we mark, the more we get paid. If we’re slow, we fall foul of exam cheat No 1: the exam board.

Take it from an examiner, your students’ A-level results could easily be wrong

It doesn’t matter whether you teach economics with ABC board or further maths with XYZ, they are as rotten as each other. My board ask for two qualifications from their examiners: they are alive and they need the cash.

Mr Simpson turns up year after year marking different papers in my subject because the exam board doesn’t cross reference sackings with recruitment. Think of him as a zombie – we declare them dead, but they reappear. Simpson is “aberrant”, in examiner parlance. This means that when we look at his marking, some scores are too generous, some are too mean and there is no pattern. Fancy having him mark your students’ papers? Ms Griffin, however, is merely a “lingering doubt”. These markers make big mistakes, but there is a consistent generosity or meanness that we can correct.

Speaking of consistency, here’s exam cheat No 2: Ofqual. The quango is charged with ensuring compatibility between the exam boards but its heavy-handed, ruthlessly statistical approach makes everything much worse. Unless exam boards give 80% of their marks to Ofqual by early July, they face severe sanctions, including public naming and shaming. Senior examiners therefore have to apply the thumbscrews to their juniors, with predictable consequences for accuracy.

In a recent report exam boards confessed to “guesstimating” grades. The only shock for me was that they admitted it. I’ve seen a chief examiner (top of the tree in exam terms) take a set of papers from an aberrant marker and come back minutes later with new grades. Usain Bolt couldn’t have moved at that speed. The examiner had clearly just looked up the school’s predicted grades and scribbled them on top of the papers. The moral of the story is to check the grades your centre sends to the board. They are used more than you think.

If in doubt about a result, always go for a re-mark – the numbers of requests are booming. It’s hardly a surprise; some examiners are not even standardised. In standardisation, they are given a sample of pre-marked papers and tested on how well they can match the agreed marks. If they cannot, they are not allowed to continue marking. But there are thousands of orphan scripts left unmarked every summer and my board was so desperate that it summoned the zombies, the lingering doubters and other barrel scrapings to a special centre to mark against the clock. Several of these worthy souls had failed standardisation but were allowed to carry on (paid at several times the normal rate).

It gets worse; there are gangsters out there. I’ve seen papers given the green light despite major reservations about how it’s been graded because an examiner needed to move on to their next marking gig. Exam cheat No 3: examiners.

Secret Teacher: marking exam papers exposes the flaws in teaching

I get paid £4 per script. There’s an adage about peanuts and primates. We genuinely don’t do it for the money, but no one likes to be exploited. Meanwhile, remarks cost £40, so someone is making a lot of money. Markers are poorly motivated and often poorly qualified. My examiners once needed several years of teaching experience, now I’ll take a PGCE student. What unites us is a genuine love of the subject we are marking and respect for the students who are producing the answers. For me, reading a good script is an emotional and resonant experience. Students deserve nothing less than my best, and I try to give it. I cannot say the same for the examining process. Your students’ marks may be right, wrong or anywhere in between.

Unexpected exam hero No 1: former education secretary Michael Gove. He was unpopular, but he had some good ideas, one of which was to reduce the exam boards to one. A single board with consistent standards, fair rules and fair results. One exam envelope. And no more zombies. Full marks, I say.

Friday, 8 May 2015

The inequity of UK's election results 2015

By Girish Menon

Party

|

Seats

|

Gain

|

Loss

|

Net

|

Vote (%)

|

Change (points)

|

Total Votes

|

Conservative

|

331

|

38

|

10

|

28

|

36.9

|

0.5

|

11.3 ml

|

Labour

|

232

|

23

|

48

|

-25

|

30.4

|

1.5

|

9.3 ml

|

Scottish National Party

|

56

|

50

|

0

|

50

|

4.7

|

3.1

|

1.4 ml

|

Lib Dems

|

8

|

0

|

49

|

-49

|

7.9

|

-15.2

|

2.4 ml

|

DUP

|

8

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0.6

|

0

|

.18 ml

|

Sinn Fein

|

4

|

0

|

1

|

-1

|

0.6

|

0

|

.17 ml

|

Plaid Cymru

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0.6

|

0

|

.18 ml

|

SDLP

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0.3

|

-0.1

|

.09 ml

|

UUP

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

2

|

0.4

|

n/a

|

.11 ml

|

UKIP

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

-1

|

12.6

|

9.6

|

3.9 ml

|

Green

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

3.8

|

2.8

|

1.1 ml

|

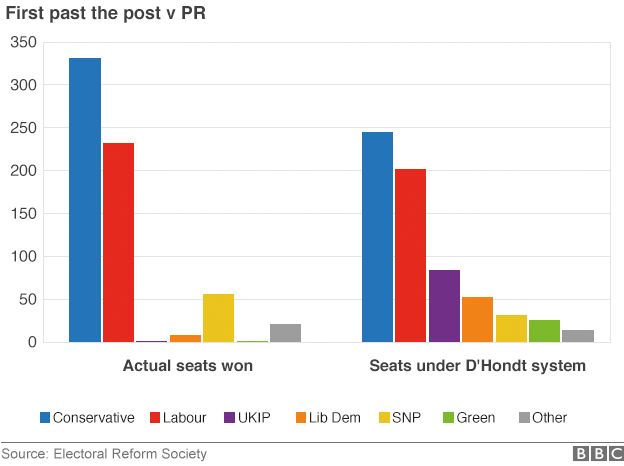

The Electoral Reform Society, a campaign group, has modelled what would have happened

under a proportional voting system that makes use of the D'Hondt method of converting votes to seats.

|

|---|

Wednesday, 26 September 2012

It's not just about the results

Paddy Upton

September 25, 2012

| |||

As cricket advances into the entertainment industry, so the celebrity limelight shines more brightly on the players. Cricketers today enjoy more money, more glamour, more exposure than ever before. It's fun, the party is on, but are they sufficiently prepared for the hangovers that lurks in the shadows?

These come in many forms and manifest themselves in the form of scuffles in nightclubs, drink driving, sexual indiscretions, drug abuse, cheating and match-fixing - sometimes driven by a celebrity's sense of being above the law, invincible, and sometimes even immortal.

Cricket stars are easily seduced into defining themselves, their self-confidence and their happiness, by their name, fame, money and the results they produce: happy when they do well in these regards, grumpy and anti-social when not. A darker shadow of the limelight is where players buy into the image of fame (of being a special person) that fans and the media create for them. As they do this, they become more alienated from themselves, losing touch of who they authentically are. They begin to see themselves as superior to ordinary mortals, not only better at the skill that made them famous but also better and more important as people. They struggle to be alone, uncomfortable in their own company. Yet while surrounding themselves with others, they become incapable of genuine relationships.

A loneliness and creeping discontentment begins to shroud the star. This inner emptiness drives the celebrity to wear their "happy", "tough" or "I'm okay" masks while looking to find temporary happiness out there, in more success, fame, money, sex, drink or drugs.

Cricket has plenty of known instances of depression and substance abuse, one of the highest suicide rates of all sports, and a divorce rate to match.

It's about who you are, not what you do

There is another road, less-travelled by superstars, which leads out of the shadows of the limelight and into the light of personal and professional success, sincere relationships, lasting contentment and an all-round fulfilling life.

There is another road, less-travelled by superstars, which leads out of the shadows of the limelight and into the light of personal and professional success, sincere relationships, lasting contentment and an all-round fulfilling life.

Speaking to me in 2004, Gary Kirsten said: "I'm searching for the authentic Gary Kirsten - someone who is accepting of his shortcomings and is confident in the knowledge of who he is. One who is willing to have a positive influence and add value to society in my own unique way. I want to make a difference to people's lives and give them similar opportunities that I have had. My perception of success is not about how much money I can earn in the next ten years but rather what impact I made on people I came into contact with."

Gary spent thousands of hours mastering his strokeplay, which had brought him great success and recognition. To this pursuit of professional mastery, he added personal mastery. He often says that when the heat is on in Test cricket, it's not your skill but your character that is being tested.

In life as in cricket, it's who you are inside, your character and your values, rather than what you do, what results you achieve or possessions you gain, that will determine your contentment, enduring success and how you will ultimately be remembered.

Personal mastery is many things. It is a journey towards living successfully as an all-round human being, a tapping into your full potential. It is a commitment to learning about yourself, your mind and emotions in all situations. It is a strengthening of character and deepening of personal values. It is an increased awareness of self, others and the world around; living from the inside out, not the outside in. Peter Senge, one of the authors of the concept of personal mastery, defines it as "the discipline of personal growth and learning".

This idea may already sound too touchy-feely for the John Rambos and Chuck Norrises out there, but before dismissing the concept, know it translated to Kirsten's most successful international season, that it underpins Hashim Amla's remarkable performances, and grounds Sachin Tendulkar's extraordinary fame.

Conversely, the lack of personal mastery has undermined the personal and professional lives of many celebrities. Have you heard about the guy who was a brilliant batsman but whose peers think he is an idiot, and who after retirement had no mates? Or the one who had great talent and opportunity but never managed to deliver? We will never know the truth about all the cricket failures that may seem to have been caused by technical errors but which were actually caused by a lack in character or strength of mind, causing the player to repeatedly succumb to the fear of failure and how it would reflect on them. We all know how the likes of Hansie Cronje, Mike Tyson, Ben Johnson, Mohammad Azharuddin, Diego Maradona and Tiger Woods might be remembered.

The road to personal mastery

Personal mastery is a shift in attitude that drives a shift in behaviour.

From over-emphasising results to placing importance on the processes that set up the best chance of success; from defining one's contentment by results, to deriving contentment from the effort made in the pursuit of that result.

From worrying about what others think about you, to knowing that what others think about you is none of your business. There are people who don't like Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi or Mother Teresa, so what makes you so special that everyone should like you?

From focusing on the importance of looking good outwardly, to the importance of inner substance and strength of character. It is not about trying to be a good person but allowing the good person in you to emerge;

Personal mastery is a shift from thinking you have the answers, to knowing you have much to learn. From balancing talking and telling with listening and asking. People who think they're "important" seldom ask questions;

It is a shift from pretending to be strong and in control, and from covering up ignorance, faults and vulnerabilities, to acknowledging these human fallibilities while still remaining self-confident. The current South Africa team now openly acknowledges that they have choked in big tournaments in the past, and they're not choked up by this acknowledgement;

When things go wrong, personal mastery is a shift from pointing fingers and blaming others, to taking responsibility. It is first asking "What was my part in this?" before looking elsewhere. It's a shift from being reactive, to being proactive; from withdrawing or getting pissed off by criticism, to accepting that it's one of the few things that helps us grow.

It is about developing social, emotional and spiritual intelligence, in addition to building muscle and sporting intelligence - in the way that Kirsten added the journey of personal mastery to that of professional mastery.

It is a shift from an attitude of expecting things to come to you, to earning your dues through your own effort; and then being grateful for what does come.

It's a shift from focusing on yourself, to gaining awareness of what is going on for others and the world around you. Not everyone is naturally compassionate, but everyone can be aware.

| When things go wrong, personal mastery is a shift from pointing fingers and blaming others, to taking responsibility. It is first asking "What was my part in this?" before looking elsewhere | |||

Personal mastery is a shift from expecting to be told what to do, to taking responsibility for doing what needs to be done. A shift towards becoming your own best teacher as you learn more deeply about your game, your mind and your life, in a way that works best for you. Kirsten insists that players make decisions for themelves, that bowlers set their own fields, and batters take responsibility for their game plans, decisions and executions. Off the field there are no rules to govern behaviour, no curfews, no eating do's and dont's, and no fines system. Players are asked to take responsibility for making good decisions for themselves, at least most of the time.

Personal mastery is about pursuing success rather than trying to avoid failure. It is an acceptance that failure paves the path towards learning and success. It's important in this regard that leaders are okay with their players' mistakes. Almost every sports coach I have watched display visible signs of disappointment when a player makes a mistake. I wonder if these same coaches tell their players to go and fully express themselves? If they do, then their words and their actions do not line up - and their reactions speaks more loudly than their words. Show me a coach who reacts negatively to mistakes, and I will show you a team that plays with a fear of failure.

It is about knowing and playing to your strengths, rather than dwelling on your weaknesses, knowing that developing strengths builds success far more effectively than fixing weaknesses does. If you're a good listener, it's about being even better, for instance.

It requires an awareness of how you conduct yourself in relation to basic human principles, such as integrity, honesty, humility, respect and doing what is best for all. It means having an awareness of and deliberately living personal values as one goes about one's business. It's about knowing how one day you want to be remembered as a person - and then living that way today.

When you, as a top athlete, do well, it's about receiving the praise fully, and expressing gratitude in equal proportion, knowing that no athlete achieves success without the unseen heroes that support them. Praise plus gratitude equals humility. One only need listen to Amla receiving a Man-of-the-Match award to witness humility.

Personal mastery is a path that leads through all of life, bringing improved performances on the field and a more contented and rewarding life off of it. It's a journey out of the shadows of the ego and into the light of awareness; it's a daily commitment, not a destination. It may not be for John Rambo or Chuck Norris, but it works for most.

The bonus is that while personal mastery leads to a happier and more rewarding existence, it also leads to better sport performance. Kirsten adds: "I spent years fighting a mental battle with my pereived lack of skill. Towards the end of my career I dropped this, as well trying to live up to others expectations. I went on to score five Test centuries and have my best year ever. As a coach, I now know that managing myself and others well, being aware of who I am being and why I do things, is of far more importance than technical knowledge of the game."

Another fairly successful and likeable international cricketer who knows the importance of personal mastery states: "Who I am as a person, my nature, is permanent. My results on the field are temporary - they will go up and go down. It is more important that I am consistent as a person. This I can control, my results I cannot." He adds that "people will criticise me for my results, and will soon forget them, but they will always remember the impact I have on them as a person. This will last forever." His name is Sachin Tendulkar.

Paddy Upton is South Africa's performance director.

Thursday, 3 May 2012

Markets can't magic up good teachers. Nor can bonuses

Monetising incentives in education in the name of social mobility assumes everything improves with a price on it. But it doesn't

Illustration by Matt Kenyon

So, in the field of unemployment, it was actually the last government which introduced a payment-by-result system, though nobody realised then what a rip-off it was, because of the commercial confidentiality clauses that somehow let the spending of public money off the hook of public scrutiny. In the prison system, the thrilling new hope was the social impact bond, first introduced by Jack Straw, where investors could plough cash into programmes to reduce reoffending, and when they got results, the government would pay out.

Payment by results is circling addiction charities like a vulture, often cited as the top anxiety for the third sector, who point out that you might have tremendous results for one year and terrible results for the next. That's addiction for you – it doesn't track upward in a steady trajectory; it's chaotic.

And now the education committee's ninth report, published last week, suggests that teachers might achieve more if their students' grades were reflected in their pay. What we're looking at, in a variety of forms, is the marketisation of public services. And even though it's already well in progress, shall we just take a second to ask how well it works, before we carry on?

The short answer is that it doesn't. It has been noted by researchers that, when you use a quantitative indicator (like cash), corruption pressures occur. "When the Department of Labor attempted to reward local agencies for placing the unemployed in jobs, the agencies increased placement rates by getting more workers into more easily-found short-term poorly paid jobs, and fewer into harder-to-find but more skilled long-term jobs."

It is only the spelling of labour that gives this away as an American study. Meanwhile, in the UK the service company A4e stands accused of sending people on training courses that were simply them in a room with a broken computer; harrying people into working voluntarily for A4e itself, work that was often (this bit is genuinely priceless) the training of other unemployed people, in how not to be unemployed; placing long-term unemployed people with charities and co-operatives, who undertook their training while A4E walked off with the money (result!). Let's not even get started on what Emma Harrison, the head of A4e, paid herself: let it be enough to say that the kind of people who are motivated mainly by money are rarely the same people who care what happens to the unemployed.

Dashing just briefly through the prison service, I remain unable to see any real difference between a payment-by-result approach for the reduction of reoffenders, and ordinary targets for reducing the same. Payment by results is just a target with a price tag.

And that being the case, surely everything the coalition has said about the last government's targets – that they distorted the aims of public service, created perverse incentives and added layers of bureaucracy – would also be true of a payment-by-result system. But I sought clarity once from Nick Herbert, minister for policing and criminal justice, and he simply refuted any similarity by bare assertion. It isn't the same as a target, because I say it isn't. It was like trying to argue with Eminem.

Moving on to education, the most virgin terrain in this landscape, the argument for payment by results is as follows: the Sutton Trust found that good teachers are the single greatest factor in improving social mobility. Therefore if you raise teaching standards you stimulate social mobility.

The flaw here is that it doesn't follow that good teaching is engendered by specific financial rewards. It's quite possible that teachers entered the field in the first place because they weren't that interested in competing for money.

In the US, they've been experimenting with payment-by-result systems for years. And mainly the outcomes are poor; occasionally, a state might throw up a programme that works (Texas's system seems to work in a modest way). But my main reservation is that America is a stupid country to be looking to in the first place, when it has the worst results for state-educated pupils, which correlates neatly with its status as one of the most unequal countries in the OECD. It is absolutely nonsensical to be trying to pick apart the US system to find the bits that work slightly better than all the bits that don't work at all.

Why can't we take as our starting point a nation whose 15 year-olds have maths and literacy scores we'd actually want to emulate? Countries where inequality is very high tend to be the same as the ones who think that everything will get better once you put a price on it. Then when things don't improve, they think the problem is their bonuses weren't sufficiently well designed. It never seems to occur to them that there are mines deeper than silver and gold.

Thursday, 12 April 2012

When is poor form just randomness?

Ed Smith in Cricinfo

There is a nasty moment in the career of every coach or captain when he

looks around the dressing room during one of his own team talks and asks

himself the startling but pertinent question, "Who am I talking to?

These words, these exhortation, these commands - who are they aimed at?

Who do I want to be listening? Is anyone? And should anyone be listening, even to me?"

And yet all captains were once themselves in the ranks, so they must

still remember the days when they were among the non-listeners rather

than the un-listened to. One colleague of mine kept a newspaper

crossword (unobtrusively placed next to his left thigh) to look at

during every team talk. As the coach yelled and blamed players, my

team-mate would nod sagely, as if in agreement. But he wasn't nodding

about the team talk at all; he was nodding in satisfaction at having

cracked nine across.

And I don't blame him. In fact, the ability to tune out of team talks is

a vital preliminary for preserving your sanity as a player. Why?

Because cricket is a very difficult game to generalise about and because

it is very rare that all the components of a team underperform

simultaneously. Far more often - after any day's play - the dressing

room contains a wide variety of individual performances. So why should a

player who has prepared optimally and performed admirably allow his

mood to be ruined by a team talk that is aimed entirely at someone else?

Cricket is famously a team game played by individuals - a fact it is

all too easy to forget when you are speaking to the whole team.

Look at England's performances in Test matches this winter and ask

yourself what changed between the abject failures of Pakistan and the

superb victory of the second Test in Colombo?

The bowling? No change - it was excellent throughout. The wicketkeeping?

No change. The fielding? No change. The body language? A symptom rather

than a cause. The team mentality? No change that I could discern. The

effort and discipline? No change that I could pick up.

The difference was very simple: England succeeded in getting runs in

Colombo where they failed to get runs in the UAE and in Galle. Only one

element of their game had been problematic. And once England's batting

was fixed - or fixed itself - the team returned to winning ways and

preserved their status as the No. 1-ranked Test team in the world.

It is alarmingly simple. All that disappointment and suffering - the

defeats, the soul searching, the media criticism, the frankly baffling

idea that Andrew Strauss ought to be sacked as captain, and the barking

mad suggestion that Kevin Pietersen was no longer good enough - it was

all caused by something utterly straightforward: England's six frontline

batsmen simply weren't scoring enough runs.

How can we explain the fact that so many good players were out of form

simultaneously? The coach, Andy Flower, was typically self-critical in

blaming the team's preparation for the batting failures earlier this

winter. I have a different theory. England's collective batting woes did

not necessarily have a direct "cause" of the sort that journalists and

fans like to believe must always exist. It may not have been a question

of effort or preparation or even collective mood.

Team batting failures are sometimes caused by the simple fact of

randomness. What do I mean by randomness? Imagine the career scores of

each batsman in the team printed in sequence on a piece on paper. It

would look like a cardiogram - the upward spikes are the hundreds, the

lowest points are the zeroes. Now imagine six of these cardiograms - one

for each of the team's batsmen - laid one above the other on the same

page.

| England's collective batting woes did not necessarily have a direct "cause" of the sort that journalists and fans like to believe must always exist. It may not have been a question of effort or preparation or even collective mood | |||

If the same batting team stays together for a long enough period of time

- and England's selection policy is very stable - there will inevitably

be a time at which all six of the cardiograms are at a low

point. Obviously this is a catastrophe for the team: no one is getting

any runs! But it does not follow that the batsmen are slacking or the

coaches are useless or the tactics are flawed. It really is just one of

those things.

The question, and it is a hugely problematic one, is: how can we know if

it really was random rather than "caused" by errors of approach and

application? There is no complete answer to that. It is a question of

judgement; and good judgement is what singles out the top coaches and

captains.

The best coach I've ever worked with constantly used to ask if what

everyone else was calling "form" was in fact randomness. When my team

was bowled out for a low score, he'd say, "Did you actually bat badly?

Or did you just nick everything?" He meant that sometimes the ratio of

edges to plays-and-misses is unusually high. The underlying logic is

important: it is a sign of wisdom not to draw too many conclusions from a

small sample of outcomes.

If this coach sounds like a soft touch, don't be fooled. He sometimes

asked the same question in reverse form when we won. He would shock me

by saying, "You won, but for much of the game you were outplayed. I

think you need to consider changes." The point - a point that most

students of sport entirely miss - is that the foundations of lasting

success are built on the correct assessment of a team's fundamentals:

its ability, its cohesion, its discipline and preparation. Those

fundamentals change slowly, and it is easy to misinterpret a random

fluctuation as a fundamental crisis.

Look at other sports. Last autumn, after a string of defeats, Arsenal

languished at the bottom of the Premier League. There was a clamour for

Arsene Wenger, their superb manager, to be sacked - despite his stellar

record of producing successful teams while also balancing the budget.

Does anyone now believe that Arsenal would have recovered so brilliantly

(they are third in the table and set for yet another year of

qualification for Europe) under a different manager? No, what was

required was for Arsenal's board and fans to hold their nerve instead of

over-react to a small sample of poor results.

The same applies to this England team. They had a shock this winter.

They are right to ask themselves tough questions about how such a good

team lost four consecutive Test matches. But they would be wrong to

think it is because they are picking the wrong players or have the wrong

captain.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)