Monetising incentives in education in the name of social mobility assumes everything improves with a price on it. But it doesn't

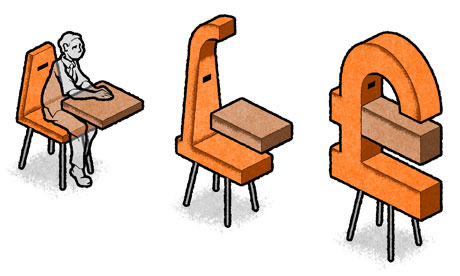

Illustration by Matt Kenyon

So, in the field of unemployment, it was actually the last government which introduced a payment-by-result system, though nobody realised then what a rip-off it was, because of the commercial confidentiality clauses that somehow let the spending of public money off the hook of public scrutiny. In the prison system, the thrilling new hope was the social impact bond, first introduced by Jack Straw, where investors could plough cash into programmes to reduce reoffending, and when they got results, the government would pay out.

Payment by results is circling addiction charities like a vulture, often cited as the top anxiety for the third sector, who point out that you might have tremendous results for one year and terrible results for the next. That's addiction for you – it doesn't track upward in a steady trajectory; it's chaotic.

And now the education committee's ninth report, published last week, suggests that teachers might achieve more if their students' grades were reflected in their pay. What we're looking at, in a variety of forms, is the marketisation of public services. And even though it's already well in progress, shall we just take a second to ask how well it works, before we carry on?

The short answer is that it doesn't. It has been noted by researchers that, when you use a quantitative indicator (like cash), corruption pressures occur. "When the Department of Labor attempted to reward local agencies for placing the unemployed in jobs, the agencies increased placement rates by getting more workers into more easily-found short-term poorly paid jobs, and fewer into harder-to-find but more skilled long-term jobs."

It is only the spelling of labour that gives this away as an American study. Meanwhile, in the UK the service company A4e stands accused of sending people on training courses that were simply them in a room with a broken computer; harrying people into working voluntarily for A4e itself, work that was often (this bit is genuinely priceless) the training of other unemployed people, in how not to be unemployed; placing long-term unemployed people with charities and co-operatives, who undertook their training while A4E walked off with the money (result!). Let's not even get started on what Emma Harrison, the head of A4e, paid herself: let it be enough to say that the kind of people who are motivated mainly by money are rarely the same people who care what happens to the unemployed.

Dashing just briefly through the prison service, I remain unable to see any real difference between a payment-by-result approach for the reduction of reoffenders, and ordinary targets for reducing the same. Payment by results is just a target with a price tag.

And that being the case, surely everything the coalition has said about the last government's targets – that they distorted the aims of public service, created perverse incentives and added layers of bureaucracy – would also be true of a payment-by-result system. But I sought clarity once from Nick Herbert, minister for policing and criminal justice, and he simply refuted any similarity by bare assertion. It isn't the same as a target, because I say it isn't. It was like trying to argue with Eminem.

Moving on to education, the most virgin terrain in this landscape, the argument for payment by results is as follows: the Sutton Trust found that good teachers are the single greatest factor in improving social mobility. Therefore if you raise teaching standards you stimulate social mobility.

The flaw here is that it doesn't follow that good teaching is engendered by specific financial rewards. It's quite possible that teachers entered the field in the first place because they weren't that interested in competing for money.

In the US, they've been experimenting with payment-by-result systems for years. And mainly the outcomes are poor; occasionally, a state might throw up a programme that works (Texas's system seems to work in a modest way). But my main reservation is that America is a stupid country to be looking to in the first place, when it has the worst results for state-educated pupils, which correlates neatly with its status as one of the most unequal countries in the OECD. It is absolutely nonsensical to be trying to pick apart the US system to find the bits that work slightly better than all the bits that don't work at all.

Why can't we take as our starting point a nation whose 15 year-olds have maths and literacy scores we'd actually want to emulate? Countries where inequality is very high tend to be the same as the ones who think that everything will get better once you put a price on it. Then when things don't improve, they think the problem is their bonuses weren't sufficiently well designed. It never seems to occur to them that there are mines deeper than silver and gold.

No comments:

Post a Comment