'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Friday, 5 January 2024

Friday, 21 July 2023

A Level Economics 70: The Impact of Government Failures on Economic Actors

Government intervention failures can have significant and varied effects on economic actors and citizens. Real-life examples illustrate how these failures impact various aspects of the economy and society:

1. Economic Inefficiency: In the 1970s, India implemented the License Raj system, requiring businesses to obtain licenses for various activities. This intervention led to bureaucratic red tape, delays, and corruption. The system stifled economic growth, discouraged entrepreneurship, and resulted in inefficient allocation of resources.

2. Reduced Economic Growth: In Venezuela, price controls were imposed on essential goods like food and medicine to address inflation. However, the price controls led to shortages, hoarding, and black markets, ultimately undermining the country's economic growth and exacerbating its economic crisis.

3. Higher Costs: The U.S. government's attempt to subsidize the ethanol industry for fuel production led to unintended consequences. Corn prices surged due to increased demand for ethanol production, affecting food prices and leading to higher costs for consumers.

4. Distorted Incentives: In some countries, agricultural subsidies intended to support farmers' incomes created incentives for overproduction, leading to surpluses and contributing to trade disputes on the international stage.

5. Unequal Outcomes: Government interventions in housing markets, such as rent control policies, can lead to housing shortages and unequal access to affordable housing for low-income citizens.

6. Diminished Investment: Uncertainty and frequent policy changes in a country's tax laws or regulations can discourage foreign and domestic investments, hampering economic growth and job creation.

7. Erosion of Trust: A series of government corruption scandals and ineffective responses to economic crises in certain countries have eroded public trust in government institutions and leadership, leading to social unrest and political instability.

8. Political Instability: The failure of the government to address issues of inequality and social discontent in some countries has resulted in political unrest and mass protests, leading to instability and disruption of economic activities.

9. Loss of Freedom: Restrictive government regulations on certain industries can limit individuals' and businesses' freedom to make choices and adapt to changing market conditions.

10. Disruptions to Social Programs: Inadequate implementation of social programs like healthcare and education can result in reduced access to essential services for citizens, particularly those in marginalized communities.

11. Wasted Resources: Inefficient government spending on large-scale infrastructure projects that yield little economic benefit or face significant delays can waste valuable resources.

12. Environmental Consequences: Government policies meant to address environmental issues may have unintended negative consequences. For instance, subsidizing fossil fuels to keep energy prices low can discourage investment in renewable energy sources and exacerbate climate change.

Conclusion: Government intervention failures can have far-reaching effects on economic actors and citizens, impacting economic growth, efficiency, individual freedoms, and overall societal well-being. Learning from past mistakes and adopting evidence-based policies is essential to avoid such failures and create effective interventions that address market failures without causing unnecessary harm to the economy and citizens. Regular evaluation, transparency, and responsiveness to feedback can help mitigate the negative effects of government intervention failures and promote better outcomes for all.

Friday, 23 June 2023

Economics Explained: Why do 'smart and educated' people display harming behaviour?

The quote mentioned is attributed to Upton Sinclair, an American writer and social reformer. It highlights the idea that people may be resistant to accepting certain truths or realities when it conflicts with their personal interests, particularly when it comes to their financial well-being.

Climate Change and Fossil Fuel Industry: The fossil fuel industry has a significant influence on the global economy, employing millions of people and generating substantial profits. However, the burning of fossil fuels is a major contributor to climate change. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence linking human activities to climate change, some individuals within the industry may deny or downplay the issue. Their salary and livelihood depend on the continued production and consumption of fossil fuels, so acknowledging the environmental consequences could jeopardize their financial interests.

Tobacco Industry and Health Risks: For decades, the tobacco industry engaged in efforts to downplay the health risks associated with smoking. Studies have consistently shown that smoking causes severe health problems, including cancer, heart disease, and respiratory issues. However, the tobacco industry funded research and disseminated misinformation to create doubt and prevent public awareness. Executives within the industry, whose salaries were tied to tobacco sales, had a vested interest in maintaining the status quo despite the harmful effects on public health.

Corporate Lobbying and Regulation: Various industries engage in lobbying activities to influence government policies and regulations that could impact their business operations. In some cases, this lobbying can lead to the blocking or dilution of regulations that would protect public health, safety, or the environment. Those employed by these industries often participate in lobbying efforts to protect their company's profits and job security, even if it means disregarding the potential negative consequences for society at large.

Conflict of Interest in Research: Researchers who receive funding from certain industries or organisations may face conflicts of interest that can bias their findings or interpretations. Pharmaceutical companies, for instance, may financially support clinical trials for their own drugs. In such cases, there is a risk that researchers may have a bias toward positive outcomes or downplay any adverse effects, as their salary or future research funding could be tied to the success of those drugs.

These examples demonstrate how financial incentives can create a cognitive bias that hinders individuals from fully understanding or accepting certain realities. When people's salaries or economic interests are directly linked to a particular outcome, they may be inclined to ignore or dismiss information that challenges their existing beliefs or threatens their financial stability.

---

In the context of the quote, "not understanding" does not imply a lack of intelligence or education. Rather, it refers to the act of consciously or subconsciously refusing to accept or acknowledge certain truths or realities due to personal interests or biases.

While individuals who fall into this category may indeed be highly educated and rational, their understanding may be clouded or biased by their financial dependence on a particular outcome. The quote suggests that people may be resistant to accepting information or evidence that contradicts their existing beliefs or challenges their financial interests, even if they possess the intellectual capacity to comprehend it.

In many cases, these individuals may be aware of the information or facts being presented to them, but their motivations or incentives prevent them from fully embracing or acknowledging the implications of that information. This can manifest as denial, scepticism, or selective interpretation of evidence to protect their financial interests or maintain the status quo.

It is important to note that the quote does not imply that every person in such a situation will exhibit this behaviour, nor does it suggest that all individuals with financial interests are incapable of understanding or accepting opposing viewpoints. Rather, it highlights a common tendency for some individuals to resist or downplay information that may threaten their financial well-being, regardless of their level of education or rationality.

Brand Loyalty: Brand loyalty refers to the tendency of consumers to consistently choose and support a particular brand over others. When individuals develop strong brand loyalty, they may become resistant to accepting or considering information that challenges their perception of the brand's superiority. This loyalty can be driven by emotional connections, personal experiences, or even social identity. Even when presented with evidence or information about better alternatives, individuals may continue to support their preferred brand due to the sense of identity, familiarity, or other psychological factors associated with it.

Religious Beliefs: Religious beliefs often form a significant part of a person's identity and worldview. People's religious beliefs can provide them with a sense of purpose, meaning, and moral framework. When faced with information or evidence that contradicts their religious beliefs, individuals may experience cognitive dissonance or resistance to accepting alternative perspectives. This can be particularly true when the information challenges core tenets or fundamental beliefs that are integral to their religious identity. As a result, individuals may be inclined to dismiss or rationalize conflicting information in order to maintain the coherence of their religious worldview.

In both cases, brand loyalty and religious beliefs can create cognitive biases that hinder individuals from fully understanding or accepting alternative viewpoints. The emotional, psychological, and social dimensions associated with these beliefs can strongly influence how individuals process and interpret information, leading to a resistance to accepting conflicting evidence or perspectives.

It is important to note that not all brand loyalists or religious individuals exhibit this behavior, and there are individuals who are open-minded and receptive to alternative viewpoints. However, for some individuals, brand loyalty and religious beliefs can become factors that influence their ability to objectively assess information or consider perspectives that contradict their established loyalties or deeply held beliefs.

Saturday, 10 December 2022

Thursday, 5 August 2021

Saturday, 6 June 2020

Scientific or Pseudo Knowledge? How Lancet's reputation was destroyed

The Lancet is one of the oldest and most respected medical journals in the world. Recently, they published an article on Covid patients receiving hydroxychloroquine with a dire conclusion: the drug increases heartbeat irregularities and decreases hospital survival rates. This result was treated as authoritative, and major drug trials were immediately halted – because why treat anyone with an unsafe drug?

Now, that Lancet study has been retracted, withdrawn from the literature entirely, at the request of three of its authors who “can no longer vouch for the veracity of the primary data sources”. Given the seriousness of the topic and the consequences of the paper, this is one of the most consequential retractions in modern history.

---

It is natural to ask how this is possible. How did a paper of such consequence get discarded like a used tissue by some of its authors only days after publication? If the authors don’t trust it now, how did it get published in the first place?

The answer is quite simple. It happened because peer review, the formal process of reviewing scientific work before it is accepted for publication, is not designed to detect anomalous data. It makes no difference if the anomalies are due to inaccuracies, miscalculations, or outright fraud. This is not what peer review is for. While it is the internationally recognised badge of “settled science”, its value is far more complicated.

At its best, peer review is a slow and careful evaluation of new research by appropriate experts. It involves multiple rounds of revision that removes errors, strengthens analyses, and noticeably improves manuscripts.

At its worst, it is merely window dressing that gives the unwarranted appearance of authority, a cursory process which confers no real value, enforces orthodoxy, and overlooks both obvious analytical problems and outright fraud entirely.

Regardless of how any individual paper is reviewed – and the experience is usually somewhere between the above extremes – the sad truth is peer review in its entirety is struggling, and retractions like this drag its flaws into an incredibly bright spotlight.

The ballistics of this problem are well known. To start with, peer review is entirely unrewarded. The internal currency of science consists entirely of producing new papers, which form the cornerstone of your scientific reputation. There is no emphasis on reviewing the work of others. If you spend several days in a continuous back-and-forth technical exchange with authors, trying to improve their manuscript, adding new analyses, shoring up conclusions, no one will ever know your name. Neither are you paid. Peer review originally fitted under an amorphous idea of academic “service” – the tasks that scientists were supposed to perform as members of their community. This is a nice idea, but is almost invariably maintained by researchers with excellent job security. Some senior scientists are notorious for peer reviewing manuscripts rarely or even never – because it interferes with the task of producing more of their own research.

However, even if reliable volunteers for peer review can be found, it is increasingly clear that it is insufficient. The vast majority of peer-reviewed articles are never checked for any form of analytical consistency, nor can they be – journals do not require manuscripts to have accompanying data or analytical code and often will not help you obtain them from authors if you wish to see them. Authors usually have zero formal, moral, or legal requirements to share the data and analytical methods behind their experiments. Finally, if you locate a problem in a published paper and bring it to either of these parties, often the median response is no response at all – silence.

This is usually not because authors or editors are negligent or uncaring. Usually, it is because they are trying to keep up with the component difficulties of keeping their scientific careers and journals respectively afloat. Unfortunately, those goals are directly in opposition – authors publishing as much as possible means back-breaking amounts of submissions for journals. Increasingly time-poor researchers, busy with their own publications, often decline invitations to review. Subsequently, peer review is then cursory or non-analytical.

And even still, we often muddle through. Until we encounter extraordinary circumstances.

Peer review during a pandemic faces a brutal dilemma – the moral importance of releasing important information with planetary consequences quickly, versus the scientific importance of evaluating the presented work fully – while trying to recruit scientists, already busier than usual due to their disrupted lives, to review work for free. And, after this process is complete, publications face immediate scrutiny by a much larger group of engaged scientific readers than usual, who treat publications which affect the health of every living human being with the scrutiny they deserve.

The consequences are extreme. The consequences for any of us, on discovering a persistent cough and respiratory difficulties, are directly determined by this research. Papers like today’s retraction determine how people live or die tomorrow. They affect what drugs are recommended, what treatments are available, and how we get them sooner.

The immediate solution to this problem of extreme opacity, which allows flawed papers to hide in plain sight, has been advocated for years: require more transparency, mandate more scrutiny. Prioritise publishing papers which present data and analytical code alongside a manuscript. Re-analyse papers for their accuracy before publication, instead of just assessing their potential importance. Engage expert statistical reviewers where necessary, pay them if you must. Be immediately responsive to criticism, and enforce this same standard on authors. The alternative is more retractions, more missteps, more wasted time, more loss of public trust … and more death.

Wednesday, 12 October 2016

Nobel prize winners’ research worked out a theory on worker productivity – then Amazon and Deliveroo proved it wrong

Financial incentives are important. We all know that’s true. If you were offered a job that paid £10 an hour and then someone else came up offering to pay you £11 an hour for identical work, which one would you choose?

Most of us would also accept that well-designed employment contracts can get more out of us. If we could take home more money for working harder (or more effectively), most of us would.

Bengt Holmstrom won the Nobel economics prize this week for his theoretical research on the optimum design for a worker’s contract to encourage the individual to work as productively as possible.

The work of Holmstrom and his fellow Nobel laureate, Oliver Hart, is subtle, recognising that the complexity of the world can cause simplistic piece-rate contracts or bonus systems to yield undesirable results.

For instance, if you pay teachers more based on exam results, you will find they “teach to the test” and neglect other important aspects of children’s education. If you reward CEOs primarily based on the firm’s share price performance you will find that they focus on boosting the short-term share price, rather than investing for the long-term health of the company.

Holmstrom and Hart also grappled with the problem of imperfect information. It is hard to measure an individual worker’s productivity, particularly when they are engaged in complex tasks.

So how can you design a contract based on individual performance? Holmstrom’s answer was that where measurement is impossible, or very difficult, pay contracts should be biased towards a fixed salary rather than variable payment for performance.

Yet when information on an employee’s performance is close to perfect, there can also be problems.

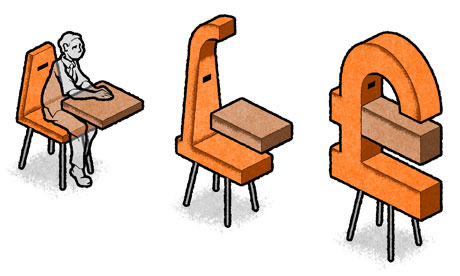

The information problem seems to be on the way to resolution in parts of the low-skill economy. Digital technology allows much closer monitoring of workers’ performance than in the past. Pickers at Amazon’s Swansea warehouse are issued with personal satnav computers which direct them around the giant warehouse on the most efficient routes, telling them which goods to collect and place in their trolleys. The devices also monitor the workers’ productivity in real time – and those that don’t make the required output targets are “released” by the management.

The so-called “gig economy” is at the forefront of what some are labelling “management by algorithm”. The London-founded cycling food delivery service app Deliveroo recently tried to implement a new pay scale for riders. The company’s London boss said this new system based on fees per delivery would increase pay for the most efficient riders. UberEats – Uber's own meal delivery service – attempted something similar.

Yet the digital productivity revolution is encountering some resistance. The proposed changes by UberEats and Deliveroo provoked strikes from their workers. And there is a backlash against Amazon’s treatment of warehouse workers.

It is possible that some of this friction is as much about employment status as contract design and pay rates. One of the complaints of the UberEats and Deliveroo couriers is that they are not treated like employees at all.

It may also reflect the current state of the labour market. If people don’t want to work in inhuman warehouses or for demanding technology companies, why don’t they take a job somewhere else? But if there are not enough jobs in a particular region, people may have no choice. The employment rate is at an all-time high, but there’s still statistical evidence that many workers would like more hours if they could get them.

Yet the new technology does pose tough questions about worker treatment. And there is no reason why these techniques of digital monitoring of employees should be confined to the gig economy or low-skill warehouse jobs.

One US tech firm called Percolata installs sensors in shops that measure the volume of customers and then compare that with the sales per employee. This allows managements to make a statistical adjustment for the fact that different shops have different customer footfall rates – it fills in the old information blanks. The result is a closer reading of an individual shop worker’s productivity.

Workers who do better can be awarded with more hours. “It creates this competitive spirit – if I want more hours, I need to step it up a bit,” Percolata’s boss told the Financial Times.

It’s possible to envisage these kinds of digital monitoring techniques and calculations being rolled out in a host of jobs and bosses making pay decisions on the basis of detailed productivity data. But one doesn’t have to be a neo-Luddite to feel uncomfortable with these trends. It’s not simply the potential for tracking mistakes by the computers and flawed statistical adjustments that is problematic, but the issue of how this could transform the nature of the workspace.

Financial incentives matter, yet there is rather more to the relationship between a worker and employer than a pay cheque. Factors such as trust, respect and a sense of common endeavour matter too – and can be important motivators of effort.

If technology meant we could design employment contracts whereby every single worker was paid exactly according to his or her individual productivity, it would not follow that we necessarily should.

Thursday, 15 October 2015

We’re not as selfish as we think we are. Here’s the proof

Do you find yourself thrashing against the tide of human indifference and selfishness? Are you oppressed by the sense that while you care, others don’t? That, because of humankind’s callousness, civilisation and the rest of life on Earth are basically stuffed? If so, you are not alone. But neither are you right.

A study by the Common Cause Foundation, due to be published next month, reveals two transformative findings. The first is that a large majority of the 1,000 people they surveyed – 74% – identifies more strongly with unselfish values than with selfish values. This means that they are more interested in helpfulness, honesty, forgiveness and justice than in money, fame, status and power. The second is that a similar majority – 78% – believes others to be more selfish than they really are. In other words, we have made a terrible mistake about other people’s minds.

The revelation that humanity’s dominant characteristic is, er, humanity will come as no surprise to those who have followed recent developments in behavioural and social sciences. People, these findings suggest, are basically and inherently nice.

A review article in the journal Frontiers in Psychology points out that our behaviour towards unrelated members of our species is “spectacularly unusual when compared to other animals”. While chimpanzees might share food with members of their own group, though usually only after being plagued by aggressive begging, they tend to react violently towards strangers. Chimpanzees, the authors note, behave more like the homo economicus of neoliberal mythology than people do.

Humans, by contrast, are ultrasocial: possessed of an enhanced capacity for empathy, an unparalleled sensitivity to the needs of others, a unique level of concern about their welfare, and an ability to create moral norms that generalise and enforce these tendencies.

Such traits emerge so early in our lives that they appear to be innate. In other words, it seems that we have evolved to be this way. By the age of 14 months,children begin to help each other, for example by handing over objects another child can’t reach. By the time they are two, they start sharing things they value. By the age of three, they start to protest against other people’s violation of moral norms.

A fascinating paper in the journal Infancy reveals that reward has nothing to do with it. Three- to five-year-olds are less likely to help someone a second time if they have been rewarded for doing it the first time. In other words, extrinsic rewards appear to undermine the intrinsic desire to help. (Parents, economists and government ministers, please note.) The study also discovered that children of this age are more inclined to help people if they perceive them to be suffering, and that they want to see someone helped whether or not they do it themselves. This suggests that they are motivated by a genuine concern for other people’s welfare, rather than by a desire to look good.

Why? How would the hard logic of evolution produce such outcomes? This is the subject of heated debate. One school of thought contends that altruism is a logical response to living in small groups of closely related people, and evolution has failed to catch up with the fact that we now live in large groups, mostly composed of strangers.

Another argues that large groups containing high numbers of altruists will outcompete large groups which contain high numbers of selfish people. A third hypothesis insists that a tendency towards collaboration enhances your own survival, regardless of the group in which you might find yourself. Whatever the mechanism might be, the outcome should be a cause of celebration.

‘Philosophers produced persuasive, influential and catastrophically mistaken accounts of the state of nature.’ Photograph: Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

So why do we retain such a dim view of human nature? Partly, perhaps, for historical reasons. Philosophers from Hobbes to Rousseau, Malthus toSchopenhauer, whose understanding of human evolution was limited to the Book of Genesis, produced persuasive, influential and catastrophically mistaken accounts of “the state of nature” (our innate, ancestral characteristics). Their speculations on this subject should long ago have been parked on a high shelf marked “historical curiosities”. But somehow they still seem to exert a grip on our minds.

Another problem is that – almost by definition – many of those who dominate public life have a peculiar fixation on fame, money and power. Their extreme self-centredness places them in a small minority, but, because we see them everywhere, we assume that they are representative of humanity.

The media worships wealth and power, and sometimes launches furious attacks on people who behave altruistically. In the Daily Mail last month, Richard Littlejohn described Yvette Cooper’s decision to open her home to refugees as proof that “noisy emoting has replaced quiet intelligence” (quiet intelligence being one of his defining qualities). “It’s all about political opportunism and humanitarian posturing,” he theorised, before boasting that he doesn’t “give a damn” about the suffering of people fleeing Syria. I note with interest the platform given to people who speak and write as if they are psychopaths.

The effects of an undue pessimism about human nature are momentous. As the foundation’s survey and interviews reveal, those who have the bleakest view of humanity are the least likely to vote. What’s the point, they reason, if everyone else votes only in their own selfish interests? Interestingly, and alarmingly for people of my political persuasion, it also discovered that liberals tend to possess a dimmer view of other people than conservatives do. Do you want to grow the electorate? Do you want progressive politics to flourish? Then spread the word that other people are broadly well-intentioned.

Misanthropy grants a free pass to the grasping, power-mad minority who tend to dominate our political systems. If only we knew how unusual they are, we might be more inclined to shun them and seek better leaders. It contributes to the real danger we confront: not a general selfishness, but a general passivity. Billions of decent people tut and shake their heads as the world burns, immobilised by the conviction that no one else cares.

You are not alone. The world is with you, even if it has not found its voice.

Monday, 16 July 2012

Was the Petrol Price rigged too?

Monday, 28 May 2012

Why economics needs to be seen not as a science but a moral philosophy

Michael Sandel: 'We need to reason about how to value our bodies, human dignity, teaching and learning'

It's a pity I hadn't read What Money Can't Buy before embarking, because the folly of the chocolate button policy lies at the heart of Michael Sandel's new book. "We live at a time when almost everything can be bought and sold," the Harvard philosopher writes. "We have drifted from having a market economy, to being a market society," in which the solution to all manner of social and civic challenges is not a moral debate but the law of the market, on the assumption that cash incentives are always the appropriate mechanism by which good choices are made. Every application of human activity is priced and commodified, and all value judgments are replaced by the simple question: "How much?"

Sandel leads us through a dizzying array of examples, from schools paying children to read – $2 (£1.20) a book in Dallas – to commuters buying the right to drive solo in car pool lanes ($10 in many US cities), to lobbyists in Washington paying line-standers to hold their place in the queue for Congressional hearings; in effect, queue-jumping members of the public. Drug addicts in North Carolina can be paid $300 to be sterilised, immigrants can buy a green card for $500,000, best man's speeches are for sale on the internet, and even body parts are openly traded in a financial market for kidneys, blood and surrogate wombs. Even the space on your forehead can be up for sale. Air New Zealand has paid people to shave their heads and walk around wearing temporary tattoos advertising the airline.

According to the logic of the market, the matter of whether these transactions are right or wrong is literally meaningless. They simply represent efficient arrangements, incentivising desirable behaviour and "improving social utility by making underpriced goods available to those most willing to pay for them". To Sandel, however, the two important questions we should be asking in every instance are: Is it fair to buy and sell this activity or product? And does doing so degrade it? Almost invariably, his answers are no, and yes.

Sandel, 59, has been teaching political philosophy at Harvard for more than 30 years, and is often described as a rock star professor, such is the excitement his lectures command. In person there is nothing terribly rock star about him; he grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in Minneapolis, studied for his doctorate at Balliol college in Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, and has been married for decades to a social scientist with whom he has two adult sons. His career, on the other hand, is stratospheric.

Sandel's justice course is said to be the single most popular university class on the planet, taken by more than 15,000 students to date and televised for a worldwide audience that runs into millions. His 2009 book Justice, based upon the course, became a global bestseller, sparking a craze for moral philosophy in Japan and earning him the accolade "most influential foreign figure" from China Newsweek. If you heard a series of his lectures broadcast on Radio 4 in the spring you would have glimpsed a flavour of his wonderfully discursive approach to lecturing, which is not unlike an Oxbridge tutorial, only conducted with an auditorium full of students, whom he invites to think aloud.

In keeping with his rock star status, Sandel is currently embarked upon a mammoth world tour to promote his new book, and when we meet in London he has almost lost his voice. His next sleep, he croaks, half smiling, isn't scheduled for another fortnight, and he looks quite weak with jetlag. Understandably, then, he isn't quite as commanding as I had expected. But although I found his book fascinating – and in parts both confronting and deeply moving – in truth, until the very last pages I didn't find it quite as persuasive as I had hoped.

This may, as we'll come on to, have something to do with the fact that its central argument is harder to make in the US than it would be here. "It is a harder sell in America than in Europe," he agrees. "It cuts against the grain in America." This is truer today than ever before, he adds, for since he began teaching Sandel has observed in his students "a gradual shift over time, from the 80s to the present, in the direction of individualistic free-market assumptions". The book's rather detached, dispassionate line of inquiry into each instance of marketisation – is it fair, and does it degrade? – was devised as a deliberate strategy to "win over the very pro-market American audience" – and it certainly makes for a coolly elegant read, forgoing rhetoric for forensic examination in order to engage with free market economics in terms the discipline understands. But I'm just not entirely sure it works.

If, like me, you share Sandel's view that moral values should not be replaced by market prices, the interesting way to read What Money Can't Buy is through the eyes of a pro-market fundamentalist who regards such a notion as sentimental nonsense. Does he win you over then?

He certainly provides some fascinating examples of the market failing to do a better job than social norms or civic values, when it comes to making us do the right thing. For example, economists carried out a survey of villagers in Switzerland to see if they would accept a nuclear waste site in their community. While the site was obviously unwelcome, the villagers recognised its importance to their country, and voted 51% in favour. The economists then asked how they would vote if the government compensated them for accepting the site with an annual payment. Support promptly dropped to 25%. It was the potty-and-chocolate-buttons syndrome all over again. Likewise, a study comparing the British practice of blood donation with the American system whereby the poor can sell their blood found the voluntary approach worked far more effectively. Once again, civic duty turned out to be more powerful than money.

However, a true believer in the law of the market would surely argue that all this proves is that sometimes a particular marketisation device doesn't work. For them it remains not a moral debate but simply one of efficacy. Sandel writes about the wrongness of a medical system in which the rich can pay for "concierge doctors" who will prioritise wealthy patients – but to anyone who believes in markets, Sandel's objection would surely cut little ice. They would say it's a question of whether or not the system is fulfilling its purpose. If the primary purpose of a particular hospital is to save lives, then if it treats a millionaire's bruised toe while a poorer patient dies of a heart attack in the waiting room, the marketisation has clearly not worked. But if the function of the hospital is to maximise profits, then treating the millionaire's sore toe first makes perfect sense, doesn't it?

"I suspect that you have – we have – a certain idea of what a hospital is for, such that a purely profit-driven one misses the mark; it's deficient in some way; it falls short of what hospitals are properly for. You would say, wouldn't you, that that hospital – that market-driven one – is not a proper hospital. They've misidentified, really, what a hospital is for. Just as if they were a school that said: 'Our purpose isn't, really, primarily, to educate students, but to maximise revenue – and we maximise revenue by offering certain credentials, and so on,' you'd say: 'Well, that's not a proper school; they're deficient in some way.'"

I would, I agree. But a rabid rightwinger wouldn't. They would say the profit motive is in itself blameless, and pursuing it by mending people's bodies or expanding their minds is no different to making motor cars, as long as it works.

"My point is that the debate, or the argument, with someone who held that view of the purpose of the hospital would be a moral argument about how properly to understand the purpose of a hospital or a school. And, yes, there would be disagreement – but that disagreement, about purpose, would be, at the same time, a moral disagreement. I'd say 'moral disagreement', because it's not just an empirical question: How did this hospital define its mission? It's: What are hospitals properly for? What is a good hospital?"

I don't think that would convince a hardliner at all. Similarly, I imagine a hardline rightwinger might read Sandel's chapter about the practice in the US of corporations taking life insurance policies out on their staff, often unbeknown to the employees, and think: what's the problem? Sandel writes about the "moral tawdriness" of companies having a financial interest in the death of an employee, but as he doesn't suggest it would tempt them to start killing their staff, these policies would strike many on the right as a rational financial investment.

At this point Sandel begins to peer at me across the table with an expression of mild disgust and disbelief. Is this woman really, I think I can see him wondering, from the Guardian? So I explain hastily that I tried very hard to read his book wearing Thatcherite glasses.

"You tried a bit too hard," he says wryly. "You shouldn't have tried so hard. You should have gone with the flow a bit more." Which feels like a disappointing answer.

The irony is that I think Sandel would have written a more powerful book had he not tried to argue the case on free-market economists' own dry, dispassionate terms. It is, as he rightly points out, the language in which most modern political debate is conducted: "Between those who favour unfettered markets and those who maintain that market choices are free only when they're made on a level playing field." But it feels as if by engaging on their terms, he's forcing himself to make an argument with one hand tied behind his back. Only in the final chapter does he throw caution to the wind, and make the case in the language of poetry.

"Consider the language employed by the critics of commercialisation," he writes. "'Debasement', 'defilement', 'coarsening', 'pollution', the loss of the 'sacred'. This is a spiritually charged language that gestures toward higher ways of living and being." And it works, for the book suddenly makes sense to me. His closing elegy to what is lost by a society that surrenders all decisions to the market almost moved me to tears.

"Does that mean I should have just started and ended with the poetry, and forgotten about the argumentative and analytical part?" he asks. "I want to address people who are coming to this from different ideological directions." But funnily enough, I think the poetry might well do a better job of persuading those very sceptics he's trying to convert.

A fascinating question he addresses is why the financial crisis appears to have scarcely put a dent in public faith in market solutions. "One would have thought that this would be an occasion for critical reflection on the role of markets in our lives. I think the persistent hold of markets and market values – even in the face of the financial crisis – suggests that the source of that faith runs very deep; deeper than the conviction that markets deliver the goods. I don't think that's the most powerful allure of markets. One of the appeals of markets, as a public philosophy, is they seem to spare us the need to engage in public arguments about the meaning of goods. So markets seem to enable us to be non-judgmental about values. But I think that's a mistake."

Putting a price on a flat-screen TV or a toaster is, he says, quite sensible. "But how to value pregnancy, procreation, our bodies, human dignity, the value and meaning of teaching and learning – we do need to reason about the value of goods. The markets give us no framework for having that conversation. And we're tempted to avoid that conversation, because we know we will disagree about how to value bodies, or pregnancy, or sex, or education, or military service; we know we will disagree. So letting markets decide seems to be a non-judgmental, neutral way. And that's the deepest part of the allure; that it seems to provide a value-neutral, non-judgmental way of determining the value of all goods. But the folly of that promise is – though it may be true enough for toasters and flat-screen televisions – it's not true for kidneys."

Sandel makes the illuminating observation that what he calls the "market triumphalism" in western politics over the past 30 years has coincided with a "moral vacancy" at the heart of public discourse, which has been reduced in the media to meaningless shouting matches on cable TV – what might be called the Foxification of debate – and among elected politicians to disagreements so technocratic and timid that citizens despair of politics ever addressing the questions that matter most.

"There is an internal connection between the two, and the internal connection has to do with this flight from judgment in public discourse, or the aspiration to value neutrality in public discourse. And it's connected to the way economics has cast itself as a value-neutral science when, in fact, it should probably be seen – as it once was – as a branch of moral and political philosophy."

Sandel's popularity would certainly indicate a public appetite for something more robust and enriching. I ask if he thinks academia could do with a few more professors with rock star status and he pauses for a polite while before smiling. "That's a question I would rather have you answer than me, I would say." That someone as unflashy and mild-mannered as Sandel can command more attention in the US than even a rightwing poster boy academic such as Niall Ferguson must, I would say, be some grounds for optimism. On a purely personal level, I ask, is there any downside to engaging with the world through the eyes of moral philosophy, rather than simple market logic?

"None but the burden of reflection and moral seriousness."

Thursday, 3 May 2012

Markets can't magic up good teachers. Nor can bonuses

So, in the field of unemployment, it was actually the last government which introduced a payment-by-result system, though nobody realised then what a rip-off it was, because of the commercial confidentiality clauses that somehow let the spending of public money off the hook of public scrutiny. In the prison system, the thrilling new hope was the social impact bond, first introduced by Jack Straw, where investors could plough cash into programmes to reduce reoffending, and when they got results, the government would pay out.

Payment by results is circling addiction charities like a vulture, often cited as the top anxiety for the third sector, who point out that you might have tremendous results for one year and terrible results for the next. That's addiction for you – it doesn't track upward in a steady trajectory; it's chaotic.

And now the education committee's ninth report, published last week, suggests that teachers might achieve more if their students' grades were reflected in their pay. What we're looking at, in a variety of forms, is the marketisation of public services. And even though it's already well in progress, shall we just take a second to ask how well it works, before we carry on?

The short answer is that it doesn't. It has been noted by researchers that, when you use a quantitative indicator (like cash), corruption pressures occur. "When the Department of Labor attempted to reward local agencies for placing the unemployed in jobs, the agencies increased placement rates by getting more workers into more easily-found short-term poorly paid jobs, and fewer into harder-to-find but more skilled long-term jobs."

It is only the spelling of labour that gives this away as an American study. Meanwhile, in the UK the service company A4e stands accused of sending people on training courses that were simply them in a room with a broken computer; harrying people into working voluntarily for A4e itself, work that was often (this bit is genuinely priceless) the training of other unemployed people, in how not to be unemployed; placing long-term unemployed people with charities and co-operatives, who undertook their training while A4E walked off with the money (result!). Let's not even get started on what Emma Harrison, the head of A4e, paid herself: let it be enough to say that the kind of people who are motivated mainly by money are rarely the same people who care what happens to the unemployed.

Dashing just briefly through the prison service, I remain unable to see any real difference between a payment-by-result approach for the reduction of reoffenders, and ordinary targets for reducing the same. Payment by results is just a target with a price tag.

And that being the case, surely everything the coalition has said about the last government's targets – that they distorted the aims of public service, created perverse incentives and added layers of bureaucracy – would also be true of a payment-by-result system. But I sought clarity once from Nick Herbert, minister for policing and criminal justice, and he simply refuted any similarity by bare assertion. It isn't the same as a target, because I say it isn't. It was like trying to argue with Eminem.

Moving on to education, the most virgin terrain in this landscape, the argument for payment by results is as follows: the Sutton Trust found that good teachers are the single greatest factor in improving social mobility. Therefore if you raise teaching standards you stimulate social mobility.

The flaw here is that it doesn't follow that good teaching is engendered by specific financial rewards. It's quite possible that teachers entered the field in the first place because they weren't that interested in competing for money.

In the US, they've been experimenting with payment-by-result systems for years. And mainly the outcomes are poor; occasionally, a state might throw up a programme that works (Texas's system seems to work in a modest way). But my main reservation is that America is a stupid country to be looking to in the first place, when it has the worst results for state-educated pupils, which correlates neatly with its status as one of the most unequal countries in the OECD. It is absolutely nonsensical to be trying to pick apart the US system to find the bits that work slightly better than all the bits that don't work at all.

Why can't we take as our starting point a nation whose 15 year-olds have maths and literacy scores we'd actually want to emulate? Countries where inequality is very high tend to be the same as the ones who think that everything will get better once you put a price on it. Then when things don't improve, they think the problem is their bonuses weren't sufficiently well designed. It never seems to occur to them that there are mines deeper than silver and gold.

Friday, 3 February 2012

The case for the legalisation of drugs

- By Alexander Wickham

- Opinion

- Thursday, 2 February 2012 at 4:15 pm

Branson began, naturally, with cannabis. He insisted that the decriminalisation, regulation and taxation of the drug libertarians have traditionally seen as a start-point for reform would reap widespread rewards for society as a whole. Responsibility for drugs policy should shift from the Home Office to the Department of Health, he argued, quite compellingly enquiring of his inquisitors whether, upon finding out that their own son or daughter had a drug problem, would they rather seek medical help or be having to deal with the police? Tellingly, they offered no answer. In Portugal, where even heroin addicts are hospitalised rather than arrested, drug use has fallen by 50% as a result of legalisation. Each year some 75,000 young Britons have their futures ruined by receiving criminal records for minor drugs offences. Treating drug users as patients rather than criminals would be an important first step to a more effective drugs policy.

Following decriminalisation, Branson admitted that regulation would inevitably be required. I have previously argued that carefully regulating the legal sale of drugs would do more than anything else to save lives. Last November two young men died after taking a fatally potent form of ecstasy (MDMA) at a London music venue. Due to the covert nature of acquiring drugs they had no way of knowing what they were buying; drug dealers are not thoughtful enough to label their products with an ingredients sticker. At present drug users are clueless about whether they are actually taking what they think they are, the extent to which it has been cut with other noxious substances, or even if they have been given a new and untested form of drug. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to work out why people are dying. Legalisation and regulation would require sellers – licensed by the state – to only offer a genuine product with clear guidelines for safe usage. It may have saved the lives of the two young men last November, and would save countless more in the future.

If the practical case for a more liberal drugs policy is fairly straightforward, the economic argument is somewhat more complex. Branson convincingly articulated the basics last week. Home Office figures show that £535 million of taxpayers’ money is spent each year on the enforcement of laws relating to the possession or supplying of drugs. Conversely, only 3% of total expenditure on drugs is through health service use, and just 1% on social care. A staggering 20% of all police time is devoted to arresting drug users and sellers. The balance between policing and treatment clearly seems skewed, but in this age of austerity these figures are especially unforgivable. At a time when the Coalition is controversially cutting welfare, why do we accept huge spending on a law and order policy that has failed to reduce the prevalence of drugs in society? As Branson succinctly puts it, the money saved through decriminalisation and taxation would surely be better spent elsewhere: ‘it’s win-win all round’.

Now on to the more technical side of things. While the supply-side economist Milton Friedman is of course celebrated for his writings on neo-liberalism, his less well-known contribution to the debate on drugs was also quite brilliant. Friedman argued that the danger of arrest has incentivised drug producers to grow more potent forms of their products. The creation of crack cocaine and stronger forms of cannabis (and evidently MDMA as shown above) is, he claims, the direct result of criminalisation encouraging producers to strive for a more attractive risk-reward ratio. Moreover, drug prohibition directly causes poverty and violent crime. Supply is suppressed by interdiction and prosecution therefore prices rise. Users are forced by their addictions to pay the going rate, then turn to crime to fund their habit as they are plunged into poverty. Finally, and perversely, the government effectively provides protection for major drug cartels. Producing and selling drugs is a risky and expensive business so only serious organised crime gangs can afford to stay in the game. All the money goes to the top. It is, as Friedman notes, ‘a monopolist’s dream’.

The deleterious and unforeseen economic consequences of criminalisation are, one you get your head round them, pretty persuasive. There is, however, one last point worth considering: the moral perspective. You may hate the idea of drugs, most people do. Yet what right does the state have to tell someone what they can and cannot do in the privacy of their own home? John Stuart Mill, the great liberal philosopher, famously declared that ‘the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not sufficient warrant’. The act of taking drugs is an entirely personal choice that affects no one but the individual himself. Can the state therefore justify impinging upon his personal liberty? Mill would say no. This is a question that deserves serious thought.

Sir Richard Branson is a maverick. A week ago most people would have been against a liberalisation of drugs policy. After listening to what Branson had to say many will have changed their minds.