'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label pain. Show all posts

Showing posts with label pain. Show all posts

Friday, 5 January 2024

Monday, 4 July 2022

Wednesday, 30 January 2019

Monday, 13 November 2017

For many, free movement causes more pain – and Brexit seems to be the cure

Deborah Orr in The Guardian

The last 16 months have made one thing clear: it’s much easier to vote to leave the EU than it is to actually leave. Remainers such as myself now find it tempting to say: “I told you so.” This, broadly speaking, is because we’re a bunch of smug know-it-alls, who haven’t even properly asked ourselves why we failed so badly to get our point across last June.

The answer, of course, is that we were and are too busy being smug know-it-alls: certain before the referendum that the idealism of the EU was plain for everyone except the terminally thick and racist to see; and certain afterwards that surely at some point even the terminally thick and racist will start having buyers’ remorse.

The sheer tragicomedy of EU-UK negotiations is indeed getting some people so fed up with the whole farrago that a few Brexiteers are crossing the floor. But, mostly, people view the difficulty of leaving the EU as yet more proof that it’s a money-grabbing, navel-gazing, inert and self-serving bureaucracy, as respectful of democracy as Kim Jong-un and as responsive to the needs of actual people as a gigantic mudslide. An in-depth survey of Brexiteers in Wales last month confirmed pretty much exactly that.

Politicians do understand, on the whole, that the factor above all others that motivates white working-class Brexit voters is free movement, as again the Welsh survey attests. This is why Labour in particular is hamstrung. Backing remain would please its Guardian-reading supporters. But that would alienate many of its core voters. Whatever Jeremy Corbyn’s own views about the EU, the sensible strategy for the short-term is not to seem at all remain-oriented.

Short-term being the operative word. The big trouble with the idealism of free movement is that its intellectual underpinnings demand pain now for future gain. The idea is that people will crisscross the various member countries, working where there’s work to create economic growth, returning home with money, experience and ideas, to start businesses that will attract others in turn, until every country is as prosperous as its neighbour.

This transformation, if it happens, will take generations. But the architects of this grand plan – the experts, the economists, the “elite” – are not the people who feel any short-term pain.

It’s completely unrealistic to ask people to spend their lives wondering where the money is coming from to pay the next electricity bill, whether their children will ever get out of their expensive private accommodation, and whether their grandchildren will be on zero-hours contracts forever, all so that maybe 80 years from now the average living standard of a Lithuanian will be similar to that of a Welshman.

People need their lives to improve now, not to live in stress and worry because things might work out in the future. The theoretical utopians who support the EU are not those who are expected to feel solidarity with their Polish colleagues in the salad-bagging factory. Especially when those colleagues are working towards a different goal. It’s easier to work for low wages if these wages are higher than you would be getting back home; easier to save when you know that a deposit on a house back home with your family is an achievable goal; easier to go without when you know that it’s for a finite time.

Where in the EU do young, unskilled British people head to get such a start in life? Reciprocity doesn’t exist.

In the 1980s, builders went to Germany, as dramatised in Auf Wiedersehen, Pet. In Germany today, builders come from eastern Europe. Wealthy countries in the EU are rightly expected to be generous. But when your own country has not generously shared its wealth with you, it’s hard to accept that you’re the ones expected to carry the burden in this grand new wealth-sharing concept.

In his book Austerity Britain, historian David Kynaston quoted evidence from the Mass Observation project that the people who lived in the areas most devastated by the war were far less likely to be optimistic about the future than those who had got off lightly. Part of their ennui was the knowledge that change had been promised after the first world war, yet hadn’t come about.

The same goes for the areas that were economically devastated in the early stages of globalisation. The EU didn’t save them then; it isn’t saving them now. No amount of promises that the EU is the best hope of shelter from economic change in the future will persuade enough of the hard-up Brexiteers in that 52% vote.

If progressives want to change the minds of Brexiteers, waiting for them to see the error of their ways isn’t going to work. What people need is a quid pro quo that offers them tangible improvements in their lives right now. That, and only that, will keep Britain in the EU.

The last 16 months have made one thing clear: it’s much easier to vote to leave the EU than it is to actually leave. Remainers such as myself now find it tempting to say: “I told you so.” This, broadly speaking, is because we’re a bunch of smug know-it-alls, who haven’t even properly asked ourselves why we failed so badly to get our point across last June.

The answer, of course, is that we were and are too busy being smug know-it-alls: certain before the referendum that the idealism of the EU was plain for everyone except the terminally thick and racist to see; and certain afterwards that surely at some point even the terminally thick and racist will start having buyers’ remorse.

The sheer tragicomedy of EU-UK negotiations is indeed getting some people so fed up with the whole farrago that a few Brexiteers are crossing the floor. But, mostly, people view the difficulty of leaving the EU as yet more proof that it’s a money-grabbing, navel-gazing, inert and self-serving bureaucracy, as respectful of democracy as Kim Jong-un and as responsive to the needs of actual people as a gigantic mudslide. An in-depth survey of Brexiteers in Wales last month confirmed pretty much exactly that.

Politicians do understand, on the whole, that the factor above all others that motivates white working-class Brexit voters is free movement, as again the Welsh survey attests. This is why Labour in particular is hamstrung. Backing remain would please its Guardian-reading supporters. But that would alienate many of its core voters. Whatever Jeremy Corbyn’s own views about the EU, the sensible strategy for the short-term is not to seem at all remain-oriented.

Short-term being the operative word. The big trouble with the idealism of free movement is that its intellectual underpinnings demand pain now for future gain. The idea is that people will crisscross the various member countries, working where there’s work to create economic growth, returning home with money, experience and ideas, to start businesses that will attract others in turn, until every country is as prosperous as its neighbour.

This transformation, if it happens, will take generations. But the architects of this grand plan – the experts, the economists, the “elite” – are not the people who feel any short-term pain.

It’s completely unrealistic to ask people to spend their lives wondering where the money is coming from to pay the next electricity bill, whether their children will ever get out of their expensive private accommodation, and whether their grandchildren will be on zero-hours contracts forever, all so that maybe 80 years from now the average living standard of a Lithuanian will be similar to that of a Welshman.

People need their lives to improve now, not to live in stress and worry because things might work out in the future. The theoretical utopians who support the EU are not those who are expected to feel solidarity with their Polish colleagues in the salad-bagging factory. Especially when those colleagues are working towards a different goal. It’s easier to work for low wages if these wages are higher than you would be getting back home; easier to save when you know that a deposit on a house back home with your family is an achievable goal; easier to go without when you know that it’s for a finite time.

Where in the EU do young, unskilled British people head to get such a start in life? Reciprocity doesn’t exist.

In the 1980s, builders went to Germany, as dramatised in Auf Wiedersehen, Pet. In Germany today, builders come from eastern Europe. Wealthy countries in the EU are rightly expected to be generous. But when your own country has not generously shared its wealth with you, it’s hard to accept that you’re the ones expected to carry the burden in this grand new wealth-sharing concept.

In his book Austerity Britain, historian David Kynaston quoted evidence from the Mass Observation project that the people who lived in the areas most devastated by the war were far less likely to be optimistic about the future than those who had got off lightly. Part of their ennui was the knowledge that change had been promised after the first world war, yet hadn’t come about.

The same goes for the areas that were economically devastated in the early stages of globalisation. The EU didn’t save them then; it isn’t saving them now. No amount of promises that the EU is the best hope of shelter from economic change in the future will persuade enough of the hard-up Brexiteers in that 52% vote.

If progressives want to change the minds of Brexiteers, waiting for them to see the error of their ways isn’t going to work. What people need is a quid pro quo that offers them tangible improvements in their lives right now. That, and only that, will keep Britain in the EU.

Thursday, 18 August 2016

How do people die from cancer?

Ranjana Srivastava in The Guardian

Our consultation is nearly finished when my patient leans forward, and says, “So, doctor, in all this time, no one has explained this. Exactly how will I die?” He is in his 80s, with a head of snowy hair and a face lined with experience. He has declined a second round of chemotherapy and elected to have palliative care. Still, an academic at heart, he is curious about the human body and likes good explanations.

“What have you heard?” I ask. “Oh, the usual scary stories,” he responds lightly; but the anxiety on his face is unmistakable and I feel suddenly protective of him.

“Would you like to discuss this today?” I ask gently, wondering if he might want his wife there.

“As you can see I’m dying to know,” he says, pleased at his own joke.

If you are a cancer patient, or care for someone with the illness, this is something you might have thought about. “How do people die from cancer?” is one of the most common questions asked of Google. Yet, it’s surprisingly rare for patients to ask it of their oncologist. As someone who has lost many patients and taken part in numerous conversations about death and dying, I will do my best to explain this, but first a little context might help.

Some people are clearly afraid of what might be revealed if they ask the question. Others want to know but are dissuaded by their loved ones. “When you mention dying, you stop fighting,” one woman admonished her husband. The case of a young patient is seared in my mind. Days before her death, she pleaded with me to tell the truth because she was slowly becoming confused and her religious family had kept her in the dark. “I’m afraid you’re dying,” I began, as I held her hand. But just then, her husband marched in and having heard the exchange, was furious that I’d extinguish her hope at a critical time. As she apologised with her eyes, he shouted at me and sent me out of the room, then forcibly took her home.

It’s no wonder that there is reluctance on the part of patients and doctors to discuss prognosis but there is evidence that truthful, sensitive communication and where needed, a discussion about mortality, enables patients to take charge of their healthcare decisions, plan their affairs and steer away from unnecessarily aggressive therapies. Contrary to popular fears, patients attest that awareness of dying does not lead to greater sadness, anxiety or depression. It also does not hasten death. There is evidence that in the aftermath of death, bereaved family members report less anxiety and depression if they were included in conversations about dying. By and large, honesty does seem the best policy.

Studies worryingly show that a majority of patients are unaware of a terminal prognosis, either because they have not been told or because they have misunderstood the information. Somewhat disappointingly, oncologists who communicate honestly about a poor prognosis may be less well liked by their patient. But when we gloss over prognosis, it’s understandably even more difficult to tread close to the issue of just how one might die.

Thanks to advances in medicine, many cancer patients don’t die and the figures keep improving. Two thirds of patients diagnosed with cancer in the rich world today will survive five years and those who reach the five-year mark will improve their odds for the next five, and so on. But cancer is really many different diseases that behave in very different ways. Some cancers, such as colon cancer, when detected early, are curable. Early breast cancer is highly curable but can recur decades later. Metastatic prostate cancer, kidney cancer and melanoma, which until recently had dismal treatment options, are now being tackled with increasingly promising therapies that are yielding unprecedented survival times.

But the sobering truth is that advanced cancer is incurable and although modern treatments can control symptoms and prolong survival, they cannot prolong life indefinitely. This is why I think it’s important for anyone who wants to know, how cancer patients actually die.

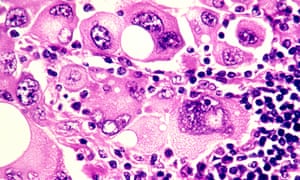

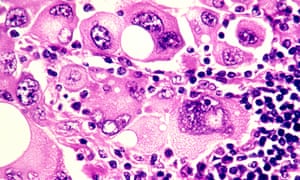

‘Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food’ Photograph: Phanie / Alamy/Alamy

“Failure to thrive” is a broad term for a number of developments in end-stage cancer that basically lead to someone slowing down in a stepwise deterioration until death. Cancer is caused by an uninhibited growth of previously normal cells that expertly evade the body’s usual defences to spread, or metastasise, to other parts. When cancer affects a vital organ, its function is impaired and the impairment can result in death. The liver and kidneys eliminate toxins and maintain normal physiology – they’re normally organs of great reserve so when they fail, death is imminent.

Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food, leading to progressive weight loss and hence, profound weakness. Dehydration is not uncommon, due to distaste for fluids or an inability to swallow. The lack of nutrition, hydration and activity causes rapid loss of muscle mass and weakness. Metastases to the lung are common and can cause distressing shortness of breath – it’s important to understand that the lungs (or other organs) don’t stop working altogether, but performing under great stress exhausts them. It’s like constantly pushing uphill against a heavy weight.

Cancer patients can also die from uncontrolled infection that overwhelms the body’s usual resources. Having cancer impairs immunity and recent chemotherapy compounds the problem by suppressing the bone marrow. The bone marrow can be considered the factory where blood cells are produced – its function may be impaired by chemotherapy or infiltration by cancer cells.Death can occur due to a severe infection. Pre-existing liver impairment or kidney failure due to dehydration can make antibiotic choice difficult, too.

You may notice that patients with cancer involving their brain look particularly unwell. Most cancers in the brain come from elsewhere, such as the breast, lung and kidney. Brain metastases exert their influence in a few ways – by causing seizures, paralysis, bleeding or behavioural disturbance. Patients affected by brain metastases can become fatigued and uninterested and rapidly grow frail. Swelling in the brain can lead to progressive loss of consciousness and death.

In some cancers, such as that of the prostate, breast and lung, bone metastases or biochemical changes can give rise to dangerously high levels of calcium, which causes reduced consciousness and renal failure, leading to death.

Uncontrolled bleeding, cardiac arrest or respiratory failure due to a large blood clot happen – but contrary to popular belief, sudden and catastrophic death in cancer is rare. And of course, even patients with advanced cancer can succumb to a heart attack or stroke, common non-cancer causes of mortality in the general community.

You may have heard of the so-called “double effect” of giving strong medications such as morphine for cancer pain, fearing that the escalation of the drug levels hastens death. But experts say that opioids are vital to relieving suffering and that they typically don’t shorten an already limited life.

It’s important to appreciate that death can happen in a few ways, so I wanted to touch on the important topic of what healthcare professionals can do to ease the process of dying.

In places where good palliative care is embedded, its value cannot be overestimated. Palliative care teams provide expert assistance with the management of physical symptoms and psychological distress. They can address thorny questions, counsel anxious family members, and help patients record a legacy, in written or digital form. They normalise grief and help bring perspective at a challenging time.

People who are new to palliative care are commonly apprehensive that they will miss out on effective cancer management but there is very good evidence that palliative care improves psychological wellbeing, quality of life, and in some cases, life expectancy. Palliative care is a relative newcomer to medicine, so you may find yourself living in an area where a formal service doesn’t exist, but there may be local doctors and allied health workers trained in aspects of providing it, so do be sure to ask around.

Finally, a word about how to ask your oncologist about prognosis and in turn, how you will die. What you should know is that in many places, training in this delicate area of communication is woefully inadequate and your doctor may feel uncomfortable discussing the subject. But this should not prevent any doctor from trying – or at least referring you to someone who can help.

Accurate prognostication is difficult, but you should expect an estimation in terms of weeks, months, or years. When it comes to asking the most difficult questions, don’t expect the oncologist to read between the lines. It’s your life and your death: you are entitled to an honest opinion, ongoing conversation and compassionate care which, by the way, can come from any number of people including nurses, social workers, family doctors, chaplains and, of course, those who are close to you.

Over 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Epicurus observed that the art of living well and the art of dying well were one. More recently, Oliver Sacks reminded us of this tenet as he was dying from metastatic melanoma. If die we must, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the part we can play in ensuring a death that is peaceful.

Our consultation is nearly finished when my patient leans forward, and says, “So, doctor, in all this time, no one has explained this. Exactly how will I die?” He is in his 80s, with a head of snowy hair and a face lined with experience. He has declined a second round of chemotherapy and elected to have palliative care. Still, an academic at heart, he is curious about the human body and likes good explanations.

“What have you heard?” I ask. “Oh, the usual scary stories,” he responds lightly; but the anxiety on his face is unmistakable and I feel suddenly protective of him.

“Would you like to discuss this today?” I ask gently, wondering if he might want his wife there.

“As you can see I’m dying to know,” he says, pleased at his own joke.

If you are a cancer patient, or care for someone with the illness, this is something you might have thought about. “How do people die from cancer?” is one of the most common questions asked of Google. Yet, it’s surprisingly rare for patients to ask it of their oncologist. As someone who has lost many patients and taken part in numerous conversations about death and dying, I will do my best to explain this, but first a little context might help.

Some people are clearly afraid of what might be revealed if they ask the question. Others want to know but are dissuaded by their loved ones. “When you mention dying, you stop fighting,” one woman admonished her husband. The case of a young patient is seared in my mind. Days before her death, she pleaded with me to tell the truth because she was slowly becoming confused and her religious family had kept her in the dark. “I’m afraid you’re dying,” I began, as I held her hand. But just then, her husband marched in and having heard the exchange, was furious that I’d extinguish her hope at a critical time. As she apologised with her eyes, he shouted at me and sent me out of the room, then forcibly took her home.

It’s no wonder that there is reluctance on the part of patients and doctors to discuss prognosis but there is evidence that truthful, sensitive communication and where needed, a discussion about mortality, enables patients to take charge of their healthcare decisions, plan their affairs and steer away from unnecessarily aggressive therapies. Contrary to popular fears, patients attest that awareness of dying does not lead to greater sadness, anxiety or depression. It also does not hasten death. There is evidence that in the aftermath of death, bereaved family members report less anxiety and depression if they were included in conversations about dying. By and large, honesty does seem the best policy.

Studies worryingly show that a majority of patients are unaware of a terminal prognosis, either because they have not been told or because they have misunderstood the information. Somewhat disappointingly, oncologists who communicate honestly about a poor prognosis may be less well liked by their patient. But when we gloss over prognosis, it’s understandably even more difficult to tread close to the issue of just how one might die.

Thanks to advances in medicine, many cancer patients don’t die and the figures keep improving. Two thirds of patients diagnosed with cancer in the rich world today will survive five years and those who reach the five-year mark will improve their odds for the next five, and so on. But cancer is really many different diseases that behave in very different ways. Some cancers, such as colon cancer, when detected early, are curable. Early breast cancer is highly curable but can recur decades later. Metastatic prostate cancer, kidney cancer and melanoma, which until recently had dismal treatment options, are now being tackled with increasingly promising therapies that are yielding unprecedented survival times.

But the sobering truth is that advanced cancer is incurable and although modern treatments can control symptoms and prolong survival, they cannot prolong life indefinitely. This is why I think it’s important for anyone who wants to know, how cancer patients actually die.

‘Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food’ Photograph: Phanie / Alamy/Alamy

“Failure to thrive” is a broad term for a number of developments in end-stage cancer that basically lead to someone slowing down in a stepwise deterioration until death. Cancer is caused by an uninhibited growth of previously normal cells that expertly evade the body’s usual defences to spread, or metastasise, to other parts. When cancer affects a vital organ, its function is impaired and the impairment can result in death. The liver and kidneys eliminate toxins and maintain normal physiology – they’re normally organs of great reserve so when they fail, death is imminent.

Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food, leading to progressive weight loss and hence, profound weakness. Dehydration is not uncommon, due to distaste for fluids or an inability to swallow. The lack of nutrition, hydration and activity causes rapid loss of muscle mass and weakness. Metastases to the lung are common and can cause distressing shortness of breath – it’s important to understand that the lungs (or other organs) don’t stop working altogether, but performing under great stress exhausts them. It’s like constantly pushing uphill against a heavy weight.

Cancer patients can also die from uncontrolled infection that overwhelms the body’s usual resources. Having cancer impairs immunity and recent chemotherapy compounds the problem by suppressing the bone marrow. The bone marrow can be considered the factory where blood cells are produced – its function may be impaired by chemotherapy or infiltration by cancer cells.Death can occur due to a severe infection. Pre-existing liver impairment or kidney failure due to dehydration can make antibiotic choice difficult, too.

You may notice that patients with cancer involving their brain look particularly unwell. Most cancers in the brain come from elsewhere, such as the breast, lung and kidney. Brain metastases exert their influence in a few ways – by causing seizures, paralysis, bleeding or behavioural disturbance. Patients affected by brain metastases can become fatigued and uninterested and rapidly grow frail. Swelling in the brain can lead to progressive loss of consciousness and death.

In some cancers, such as that of the prostate, breast and lung, bone metastases or biochemical changes can give rise to dangerously high levels of calcium, which causes reduced consciousness and renal failure, leading to death.

Uncontrolled bleeding, cardiac arrest or respiratory failure due to a large blood clot happen – but contrary to popular belief, sudden and catastrophic death in cancer is rare. And of course, even patients with advanced cancer can succumb to a heart attack or stroke, common non-cancer causes of mortality in the general community.

You may have heard of the so-called “double effect” of giving strong medications such as morphine for cancer pain, fearing that the escalation of the drug levels hastens death. But experts say that opioids are vital to relieving suffering and that they typically don’t shorten an already limited life.

It’s important to appreciate that death can happen in a few ways, so I wanted to touch on the important topic of what healthcare professionals can do to ease the process of dying.

In places where good palliative care is embedded, its value cannot be overestimated. Palliative care teams provide expert assistance with the management of physical symptoms and psychological distress. They can address thorny questions, counsel anxious family members, and help patients record a legacy, in written or digital form. They normalise grief and help bring perspective at a challenging time.

People who are new to palliative care are commonly apprehensive that they will miss out on effective cancer management but there is very good evidence that palliative care improves psychological wellbeing, quality of life, and in some cases, life expectancy. Palliative care is a relative newcomer to medicine, so you may find yourself living in an area where a formal service doesn’t exist, but there may be local doctors and allied health workers trained in aspects of providing it, so do be sure to ask around.

Finally, a word about how to ask your oncologist about prognosis and in turn, how you will die. What you should know is that in many places, training in this delicate area of communication is woefully inadequate and your doctor may feel uncomfortable discussing the subject. But this should not prevent any doctor from trying – or at least referring you to someone who can help.

Accurate prognostication is difficult, but you should expect an estimation in terms of weeks, months, or years. When it comes to asking the most difficult questions, don’t expect the oncologist to read between the lines. It’s your life and your death: you are entitled to an honest opinion, ongoing conversation and compassionate care which, by the way, can come from any number of people including nurses, social workers, family doctors, chaplains and, of course, those who are close to you.

Over 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Epicurus observed that the art of living well and the art of dying well were one. More recently, Oliver Sacks reminded us of this tenet as he was dying from metastatic melanoma. If die we must, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the part we can play in ensuring a death that is peaceful.

Monday, 18 November 2013

The Most Important Question You Can Ask Yourself Today

Mark Manson

Everybody wants what feels good. Everyone wants to live a care-free, happy and easy life, to fall in love and have amazing sex and relationships, to look perfect and make money and be popular and well-respected and admired and a total baller to the point that people part like the Red Sea when you walk into the room.

Everybody wants that -- it's easy to want that.

If I ask you, "What do you want out of life?" and you say something like, "I want to be happy and have a great family and a job I like," it's so ubiquitous that it doesn't even mean anything.

Everyone wants that. So what's the point?

What's more interesting to me is what pain do you want? What are you willing to struggle for? Because that seems to be a greater determinant of how our lives end up.

Everybody wants to have an amazing job and financial independence -- but not everyone is willing to suffer through 60-hour work weeks, long commutes, obnoxious paperwork, to navigate arbitrary corporate hierarchies and the blasé confines of an infinite cubicle hell. People want to be rich without the risk, with the delayed gratification necessary to accumulate wealth.

Everybody wants to have great sex and an awesome relationship -- but not everyone is willing to go through the tough communication, the awkward silences, the hurt feelings and the emotional psychodrama to get there. And so they settle. They settle and wonder "What if?" for years and years and until the question morphs from "What if?" into "What for?" And when the lawyers go home and the alimony check is in the mail they say, "What was it all for?" If not for their lowered standards and expectations for themselves 20 years prior, then what for?

Because happiness requires struggle. You can only avoid pain for so long before it comes roaring back to life.

At the core of all human behavior, the good feelings we all want are more or less the same. Therefore what we get out of life is not determined by the good feelings we desire but by what bad feelings we're willing to sustain.

"Nothing good in life comes easy," we've been told that a hundred times before. The good things in life we accomplish are defined by where we enjoy the suffering, where we enjoy the struggle.

People want an amazing physique. But you don't end up with one unless you legitimately love the pain and physical stress that comes with living inside a gym for hour upon hour, unless you love calculating and calibrating the food you eat, planning your life out in tiny plate-sized portions.

People want to start their own business or become financially independent. But you don't end up a successful entrepreneur unless you find a way to love the risk, the uncertainty, the repeated failures, and working insane hours on something you have no idea whether will be successful or not. Some people are wired for that sort of pain, and those are the ones who succeed.

People want a boyfriend or girlfriend. But you don't end up attracting amazing peoplewithout loving the emotional turbulence that comes with weathering rejections, building the sexual tension that never gets released, and staring blankly at a phone that never rings. It's part of the game of love. You can't win if you don't play.

What determines your success is "What pain do you want to sustain?"

I wrote in an article last week that I've always loved the idea of being a surfer, yet I've never made consistent effort to surf regularly. Truth is: I don't enjoy the pain that comes with paddling until my arms go numb and having water shot up my nose repeatedly. It's not for me. The cost outweighs the benefit. And that's fine.

On the other hand, I am willing to live out of a suitcase for months on end, to stammer around in a foreign language for hours with people who speak no English to try and buy a cell phone, to get lost in new cities over and over and over again. Because that's the sort of pain and stress I enjoy sustaining. That's where my passion lies, not just in the pleasures, but in the stress and pain.

There's a lot of self development advice out there that says, "You've just got to want it enough!"

That's only partly true. Everybody wants something. And everybody wants something badly enough. They just aren't being honest with themselves about what they actually want that bad.

If you want the benefits of something in life, you have to also want the costs. If you want the six pack, you have to want the sweat, the soreness, the early mornings, and the hunger pangs. If you want the yacht, you have to also want the late nights, the risky business moves, and the possibility of pissing off a person or ten.

If you find yourself wanting something month after month, year after year, yet nothing happens and you never come any closer to it, then maybe what you actually want is a fantasy, an idealization, an image and a false promise. Maybe you don't actually want it at all.

So I ask you, "How are you willing to suffer?"

Because you have to choose something. You can't have a pain-free life. It can't all be roses and unicorns.

Choose how you are willing to suffer.

Because that's the hard question that matters. Pleasure is an easy question. And pretty much all of us have the same answer.

The more interesting question is the pain. What is the pain that you want to sustain?

Because that answer will actually get you somewhere. It's the question that can change your life. It's what makes me me and you you. It's what defines us and separates us and ultimately brings us together.

So what's it going to be?

Monday, 10 June 2013

This battle over how Britain's military and colonial history is taught is also a battle for Britain's future

by Yasmin Alibhai Brown in The Independent

The Government has just agreed to pay £20m to over 5,000 Kenyans tortured under British rule during the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s. William Hague, in a commendably sober speech, accepted that the victims had suffered pain and grief. Out rode military expert Sir Max Hastings, apoplectic, a very furious Mad Max. Gabriel Gatehouse, the BBC Radio 4 reporter who interviewed survivors, “should die of shame”, roared the Knight of the Realm. Kenyan Human Rights organisations and native oral testimonies could not be trusted; the real baddies were the Mau Mau; no other nation guilty of crimes ever pays compensation and expresses endless guilt and finally there “comes a moment when you have to draw a line under it”. Actually Sir, the Japanese did compensate our PoWs in 2000, and Germany has never stopped paying for what it did to Jewish people.

The UK chooses to relive historical episodes of glory, and there were indeed many of those. But we also glorify those periods which were anything but glorious, and wilfully edit out the dark, unholy, inconvenient parts of the national story. Several other ex-imperial nations do the same. In Turkey, it is illegal to talk publicly about the Armenian Genocide by the Ottomans. France has neatly erased its vicious rule in Arab lands; the US only remembers its own dead in the Vietnam War, not the devastation of that country and its people. Britain proudly remembers the Abolitionists but gets very tetchy when asked to remember slavery, without which there would have been no need for Abolition. The Raj is still seen as a civilizing mission, not as a project of greed and subjugation. Not all the empire builders were personally evil, but occupation and unwanted rule is always morally objectionable. Tony Blair was probably taught too much of the aggrandising stuff and not enough about the ethics of Empire. The Scots, in any case, in spite of being totally involved, have offloaded all culpability for slavery and Empire on to the English. Their post-devolution history has been polished up well. But it is a flattering, falsifying mirror.

Indian history, as retold by William Dalrymple and Pankaj Mishra, among others, is very different from the “patriotic” accounts Britons have been fed for over a century. The 1857 Indian Uprising, for example, was a violent rebellion during which British men, women and children were murdered – so too was the Mau Mau insurrection – but the reprisals were much crueller and against many more people, many innocent. Our War on Terror is just as asymmetrical.

Today we get to hear plans to mark the centenary of the start of the First World War. The Coalition Government wants to spin this terrible conflict into another victory fest in 2014. Brits addicted to war memorialising will cheer. Michael Gove will have our children remembering only the “greatness” of the Great War and David Cameron will pledge millions of pounds for events which will stress the national spirit and be as affirming as “the diamond Jubilee celebrations”. I bet Max Hastings won’t ask for a line to be drawn under that bit of the nation’s past.

A group of writers, actors and politicians, including Jude Law, Tony Benn, Harriet Walter, Tim Pigott-Smith, Ralph Steadman, Simon Callow, Michael Morpurgo and Carol Ann Duffy has expressed concern that such a “military disaster and human catastrophe” is to be turned into another big party: “We believe it is important to remember that this was a war that was driven by big powers’ competition for influence around the globe and caused a degree of suffering all too clear in the statistical record of 16 million people dead and 20 million wounded”. After 1916, soldiers were conscripted from the poorest of families. The officer classes saw them as fodder. Traumatised soldiers, as we know, were shot. In school back in Uganda, I learnt the only words of Latin I know, Wilfred Owen’s Dulce et Decorum Est. His poems got into my heart and there they stay.

Let’s not expect the Establishment keepers of our past to dwell unduly on those facts and figures; or to acknowledge the land grabs in Africa in the latter part of the 19th-century which led to that gruesome war; or to remember how it played out on that continent. With the focus forever on the fields of Flanders, forgotten are those other theatres of that war, in East Africa, Iraq, Egypt and elsewhere.

In Tanganyika, where my mother was born, the Germans played dirty and the British fought back using over 130,000 African and Indian soldiers, thousands of them who died horrible deaths. Her father told her stories of, yes, torture by whites on both sides, trees bent over with strung up bodies, some pregnant women, and fear you could smell on people and in homes. Edward Paice’s book Tip and Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great Warin Africa, finally broke the long conspiracy of partiality.

The historical truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth matters. It is hard to get at and forever contested, but the aspiration still matters more than almost anything else in a nation’s self-portrait. With incomplete verities and doctored narratives, younger generations are bound to repeat the mistakes and vanities of the past. There will be a third global war because not enough lessons were learnt about earlier, major modern conflicts. And then our world will end.

Friday, 7 December 2012

Morphine: The cheap, effective pain-relief drug denied to millions

By Joanne Silberner PRI's The World

In the UK and US, patients who

need morphine get it - it's a different story elsewhere

In the UK and US, patients who

need morphine get it - it's a different story elsewhere

It's cheap, effective and easy to

administer - so why are millions of people around the world dying in pain,

without access to morphine?

In an open ward at Mulago Hospital in Uganda's capital city, Kampala, an elderly woman named Joyce lies in the fifth bed on the left.

She has twisted the sheets around herself, her face contorted by pain. Joyce's husband, thin and birdlike, hovers over her.

Joyce has cancer - it has spread throughout her body - and until a few days ago, she was on morphine. Then it ran out.

"She's consistently had pain," says a nurse. "And she describes the pain to be deep - kind of into her bones."

The Ugandan government makes and distributes its own morphine for use in hospitals, but poor management means the supply is erratic.

"We're in a very difficult situation," says Lesley Henson, a British pain specialist on duty at Mulago Hospital. They have patients whose pain has been kept under control with morphine - but they are running out it.

In many ways, morphine is an excellent drug for use in developing countries. It is cheap, effective, and simple and easy to administer by mouth.

Yet according to the World Health Organization, every year more than five million people with cancer die in pain, without access to morphine.

"The fact that what stands between them and the relief of that pain is a drug that costs $2 [£1.25] a week, I think is just really unconscionable," says Meg O'Brien, head of The Global Access to Pain Relief Initiative, a non-profit organisation that advocates for greater access to morphine.

O'Brien says in well-off countries, like the UK and United States, there is enough morphine to treat 100% of people in pain - but in low-income countries, it's just 8%.

In many low- and middle-income countries - 150, by some counts - morphine is all but impossible to get. Some governments don't provide it, or strictly limit it, because of concerns that it will be diverted to produce heroin.

And many doctors are reluctant to prescribe morphine, fearing their patients will become addicted.

In India, whether you can get morphine depends largely on where you are treated.

Tata Memorial Hospital, a modern and well-equipped

medical centre in Mumbai, has no problem getting morphine for patients.

"We have all the medicines necessary," says Dr Mary Ann Muckaden, head of pain relief at the hospital. "We never run out."

But in other parts of the country, it's a different story. Muckaden estimates only 1% to 2% of Indians with cancer pain get morphine.

Dinesh Kumar Yadav, 28, has come to Tata Memorial - a 30-hour bus ride from his home - to get morphine for his wife.

He tells me she is bedridden with pain but can't get morphine in the north Indian state where they live.

Dr Muckaden says part of the problem is a stifling bureaucracy.

"Many physicians in the north, they don't want to go through the rigorous licensing to store morphine," she explains.

A morphine-use map of the world

- $2 (£1.25) - cost per week per patient

- 100% - percentage of people in UK and US who have access to morphine, if they need it

- 8% - percentage in the developing world who get morphine when required

- 20% of the world's painful deaths are in sub-Saharan Africa, but only 1% of morphine use

There is a place in India where there are no barriers to

morphine. But even at the CIPLA Palliative Care Centre in the city of Pune, in

Maharashtra state, there are still challenges.

You don't see the challenges when you walk through the cool courtyard gardens with fountains and manicured walkways, or in the beautiful whitewashed buildings with large airy wards, each named after a flower.

"This is heaven on earth," says Asha Dikshit, whose mother came here last year in the last stages of breast cancer.

"She was in agony. Her shoulder had dislocated. It could not be fixed back," says Dikshit. "She had pain in the back, and sometimes there were hallucinations."

But she says her mother died - peacefully - on morphine.

Making morphine

- Comes from the opium poppy

- Discovered in 1804

- First marketed for pain relief in 1817

- Recommended by WHO for pain relief under certain conditions

Every patient here has cancer, and the care is free. The

Indian generic drug manufacturer CIPLA supplies the morphine and pays all the

other expenses.

But even with all the centre offers, the occupancy rate runs at only about 60%. One big reason, says director Priya Kulkarni, is a result of patients' own concerns about morphine. They often think morphine equals death, and they recoil when doctors suggest it.

Kulkarni says many local oncologists don't want to send patients here for that reason.

"They don't want to give up when it comes to giving them hope," she says. "And saying something like, 'I am going to refer you to a palliative specialist,' is indirectly saying 'There is nothing more I can do for you.'"

Despite all the obstacles to the use of morphine in the developing world, Kulkarni and others say things are starting to move in their direction.

In low-income countries, morphine consumption is up tenfold since 1995, according to the International Narcotics Control Board. And several countries where not many years ago there was no morphine - like Uganda - at least have some today, even if the supply is unreliable.

Back at the hospital in Kampala - where the pharmacy ran out of morphine and Joyce, the cancer patient, had to go without - palliative care specialist Leslie Henson finds a bit of luck. After leaving her patient, she steps into an office, glances at a bookshelf, and sees a forgotten bottle of morphine. It's enough to treat two or three people.

"Hopefully, we'll go take this to her and see what we can do," she says as she troops back to Joyce's room.

Soon, a doctor administers the morphine.

Joyce smiles. Her face untwists. And her husband looks ecstatic.

I ask Joyce if she's glad to get the morphine. Her husband answers. "Very much, indeed."

Other people in the hospital will remain in pain - there is not enough morphine to go around - but for the next few hours, at least, Joyce will be pain-free.

Sunday, 20 May 2012

On Migraines: they are all in the head

They

start with a spinning black penny, retch-inducing smells, impaired

thought and speech. But migraines bring odd pleasures with their pain

Dark days: when it hits, a migraine is like a film melting in your projector. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

The first time it happened I was in bed with a book, aged maybe

10. And I remember going over the same line again and again, with rising

levels of panic, as I realised I had forgotten how to read. I didn't

think it was something you could just forget. Something that, having

picked up, you could then one day drop again. I see now it was my first

migraine.

Today migraines are in the news and they're in my head, tightening around my crown like an alice band. The NHS is considering offering Botox to patients with chronic migraines. They don't know quite how it helps, but they've decided it does. The blocking of muscle contraction, which is what the botulinum toxin does to those stunning their wrinkles, hasn't been proved to relieve headaches, but two clinical trials did conclude that it led to a 10% reduction in the number of patients' headachey days. In addition, I imagine, to a laboratory paved with clingfilmed foreheads.

I'm writing now through day four of this month's headache, one that began (as do many) with a flickering blind spot in the centre of my vision. It starts small, a spinning black penny in the middle of a page. I slump in my seat as it spreads darkly over my sight like jam, and I can't see, or think, or entirely understand speech. It's the film melting in my projector – it's a bit like falling. Smells slay me. Noise, fine, but smells – Angel perfume in a lift, for instance, or that dirty spitting rain you get in cities, the kind that smells of apocalypse – will make me retch. And minutes later the headache comes.

The author Siri Hustvedt wrote about a migraine aura phenomenon called Alice in Wonderland syndrome – the migraineur feels parts of their body ballooning or shrinking. For me it's often my hand. I'll lie in bed and under my cheek it'll swell to the size of a football, or a room, or shrink until it's dust. These episodes when my reality wobbles are not entirely unpleasant.

I half-enjoy the days preceding a migraine when everything feels like déjà vu. When walking home, a series of sights – a smoking schoolgirl, a chained-up bike – are overwhelming in their impact. Everything I see reminds me of something else, but something just out of reach. It reminds me that it's reminding me, but not what it's reminding me of. In its un-graspableness, this feeling is similar to one of the factors that brings these migraines on – the reflections from the Regent's Canal that play on the ceiling above my desk. Ripples of light lead to ripples in my reality, this warm tightness behind my eyes, a grim ache in my jaw.

The pain is sometimes awful, but more often it's medicated and so simply… saddening. I take these lovely painkillers, so it's rare I'll feel the blinding sharpness. Rather than being slammed into a wall, it feels as if my head is stuck in a closing door. It's the dull agony of a deadline looming, of a nagging phobia, of going up in a lift as your vertigo builds. But I miss stuff. Parties, dinners, often meanings – I'll be interviewing somebody in a brightly lit room and will find myself two thoughts behind, my eyes scrunched in concentration, praising Olympus for the reliability of its dictaphones.

I realise, though, that it's these vibrations on the drum skin of my life that make me me. I see the world through a smoky, migrainous filter. And like somebody teetering on the edge of a depressive episode, not yet fallen, I'm able to stand outside it and look around, curiously. Medicating with Botox seems like an apt metaphor – in ironing out the migraineur's wrinkles, the doctor smooths their reality. No more hands the size of houses. No more fainting as an effect of sunlight spearing through dark trees. So I've learned to embrace this gentle madness. In succumbing to a migraine, I get to test what's real.

Today migraines are in the news and they're in my head, tightening around my crown like an alice band. The NHS is considering offering Botox to patients with chronic migraines. They don't know quite how it helps, but they've decided it does. The blocking of muscle contraction, which is what the botulinum toxin does to those stunning their wrinkles, hasn't been proved to relieve headaches, but two clinical trials did conclude that it led to a 10% reduction in the number of patients' headachey days. In addition, I imagine, to a laboratory paved with clingfilmed foreheads.

I'm writing now through day four of this month's headache, one that began (as do many) with a flickering blind spot in the centre of my vision. It starts small, a spinning black penny in the middle of a page. I slump in my seat as it spreads darkly over my sight like jam, and I can't see, or think, or entirely understand speech. It's the film melting in my projector – it's a bit like falling. Smells slay me. Noise, fine, but smells – Angel perfume in a lift, for instance, or that dirty spitting rain you get in cities, the kind that smells of apocalypse – will make me retch. And minutes later the headache comes.

The author Siri Hustvedt wrote about a migraine aura phenomenon called Alice in Wonderland syndrome – the migraineur feels parts of their body ballooning or shrinking. For me it's often my hand. I'll lie in bed and under my cheek it'll swell to the size of a football, or a room, or shrink until it's dust. These episodes when my reality wobbles are not entirely unpleasant.

I half-enjoy the days preceding a migraine when everything feels like déjà vu. When walking home, a series of sights – a smoking schoolgirl, a chained-up bike – are overwhelming in their impact. Everything I see reminds me of something else, but something just out of reach. It reminds me that it's reminding me, but not what it's reminding me of. In its un-graspableness, this feeling is similar to one of the factors that brings these migraines on – the reflections from the Regent's Canal that play on the ceiling above my desk. Ripples of light lead to ripples in my reality, this warm tightness behind my eyes, a grim ache in my jaw.

The pain is sometimes awful, but more often it's medicated and so simply… saddening. I take these lovely painkillers, so it's rare I'll feel the blinding sharpness. Rather than being slammed into a wall, it feels as if my head is stuck in a closing door. It's the dull agony of a deadline looming, of a nagging phobia, of going up in a lift as your vertigo builds. But I miss stuff. Parties, dinners, often meanings – I'll be interviewing somebody in a brightly lit room and will find myself two thoughts behind, my eyes scrunched in concentration, praising Olympus for the reliability of its dictaphones.

I realise, though, that it's these vibrations on the drum skin of my life that make me me. I see the world through a smoky, migrainous filter. And like somebody teetering on the edge of a depressive episode, not yet fallen, I'm able to stand outside it and look around, curiously. Medicating with Botox seems like an apt metaphor – in ironing out the migraineur's wrinkles, the doctor smooths their reality. No more hands the size of houses. No more fainting as an effect of sunlight spearing through dark trees. So I've learned to embrace this gentle madness. In succumbing to a migraine, I get to test what's real.

Sunday, 8 April 2012

Shouldering the pain of throwing

Andrew Leipus in Cricinfo

Able to bowl but not throw because of shoulder pain? Or maybe you have

lost power in your throw? Have to throw side-arm? Does your whole arm go

"dead" for a few seconds after you release the ball? Or you are now

experiencing a click, crunch or clunk when you lift the arm? These are

just some of the many symptoms and behaviours that can be present in the

cricketer's shoulder and which can help clinicians diagnose what your

underlying problem might be.

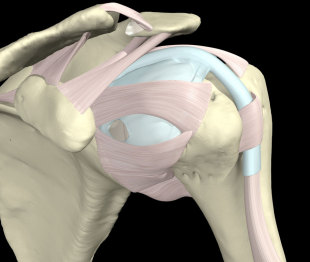

There can't be a shoulder discussion without a brief anatomy lesson. In

terms of understanding the basics, the glenohumeral joint is a shallow

ball-and-socket design, allowing a huge amount of mobility yet remaining

as stable as possible. It also has to tolerate massive torques or

rotational forces generated. Some people equate the head of the humerus

(HOH) and its relation to the scapula with a golf ball sitting on a tee,

i.e. easy to topple over. But it is actually more like trying to

balance a soccer ball on your forehead, with both the ball and the

head/body constantly moving to maintain "balance" and stop the ball from

dropping off. It is this balance between the socket joint and the

scapula position which we need to consider in the cricketer's shoulder

as it is where a lot of problems begin and where a lot of rehab

programmes fail.

As is the case with all injuries, the anatomy often lets us down by not

being able to cope with the functional demands. Some injuries develop

acutely, such as occurs with one hard throw when off balance, and some

develop over a period of time through lots of high repetition -

degenerative type injuries. The two most commonly injured structures in

cricket are the infamous rotator cuff and the glenoid labrum.

The cuff is a group of small muscles acting primarily to pull and hold

the HOH into its glenoid socket. The long head of biceps tendon assists

the rotator cuff in this role. The labrum is a circular cartilage

structure designed to "cup" or deepen this socket and provide attachment

for the biceps tendon.

An injury to the labrum results in the HOH having excess translatory

motion and not staying centred in the glenoid. The cuff then has to work

harder to compensate for this structural instability. This translation

often results in a "clunky" shoulder or one which goes "dead" when

called upon to throw at pace. Anil Kumble's shoulder had a damaged

labrum due to his high-arm legspin action. Years of repetitive stress

had detached his labrum from the glenoid, resulting in the need for

surgery. He's not alone. Muttiah Muralitharan and Shane Warne also had

shoulder surgeries in their careers. And it's not just spin bowling, as

many labral compression injuries occur during fielding when diving onto

an outstretched arm.

Injury to the cuff, however, also results in a dynamic instability,

whereby the HOH is again not held centred, and subsequently over time

stresses both the labrum and cuff. Impingement is a common term used to

describe a narrowing of the space in the shoulder that can result from

this loss of centering. The cuff doesn't actually need to be injured for

this to occur - repetitive throwing can tighten the posterior cuff

muscles and effectively "squeeze" the HOH out of its normal centre of

rotation in the glenoid. It really is a vicious circle and cricketers

compound any underlying dysfunction by the repetitive nature of the

game. They might not throw much in a match but when they do it is

usually with great speed. The bulk of the throwing volume occurs during

their practice sessions.

And when talking about shoulder mechanics we need to also understand

critical role of the scapula. In order to ensure that the HOH remains

remain centred in the glenoid, the scapula must slide and rotate

appropriately around the chest wall (that soccer ball example). Any

dysfunction in scapula movement is typically evidenced by a "winging"

motion when the arm is elevated or by observing the posture of the upper

back. Whether the winging comes before the injury or as a consequence

is hotly debated. Either way it needs to function properly. And to

complicate things even further, the thoracic spine also needs to be able

to extend and rotate fully to allow the scapula to move. Kyphotic or

slouched upper backs are terrible for allowing the arm to reach full

elevation and is a big contributor to shoulder problems.

It should be clear that in order for a cricketer's shoulder to be

pain-free, there needs to be a lot of dynamic strength and mobility of

the upper trunk and shoulder girdle. But throwing technique is equally

critical to both performance and injury prevention. Studies have shown

that the shoulder itself contributes only 25% to the release speed of

the ball. To impart this 25%, the angular velocity of the joint can

reach 7000 degrees per second. However, what is interesting is that a

whopping 50% is contributed by the hips and trunk when the player is in a

good position for the throw (allowing for a coordinated weight

transfer). But when off-balance and shying at the stumps, as often

occurs within the 30-yard circle, the shoulder alone can be called upon

to produce more than its usual load. Thus it is important to remember

that throwing should be considered as a whole body skill.

|

|||

Often a player will be able to bowl without experiencing symptoms, but

will struggle to throw. In these cases, it is common to find pathology

involving the long head of biceps or where it anchors superiorly onto

the labrum. The latter is also commonly known as a SLAP lesion. In the

transition from the cocking to acceleration phase of throwing, the

shoulder is forcefully externally rotated. The biceps is significantly

involved in stabilising the HOH at this point and often pulls so hard

that it peels the labrum off the glenoid, giving symptoms of pain and

instability. The overhead bowling action, however, does not put the

shoulder into extremes of external rotation and hence symptoms do not

usually occur. If pain is experienced during the release phase of

throwing then there is a good chance that technique is again at fault.

In order to decelerate the arm after the ball is released, the trunk and

arm need to "follow through", using the big trunk muscles and weight

shift towards the target. Failure to do this results in a massive

eccentric load on the biceps tendon, also potentially tugging on its

anchor on the glenoid. Throwing side-arm to avoid extremes of external

rotation and pain is a common sign that all is not well internally.

As you can see, an injury to the shoulder is not a simple problem. And

there are many other types of pathology found. It requires thorough

assessment and management of a host of potential contributing factors

which are mostly modifiable when identified. And whilst a lot can go

wrong in a cricketer's shoulder, there is a lot that can be done to make

sure it stays strong and healthy. Because prevention is always better

than surgery in terms of outcomes, next week I'll discuss some shoulder

training and injury prevention tips used by elite cricketers.

Tuesday, 4 October 2011

Everybody Hurts - aka Weltschmertz

By Pritish Nandy in the Times of India

We all live with weltschmerz in these difficult times. There's no exact translation of this charming word coined by Jean Paul Richter in 1810. What it suggests is a kind of world weariness that has entered our lives. What you can call a universal pain. Everyone lives with it and yet everyone is in denial of it. That's why we have this great love affair with the entertainment business. Movies. Broadway. Vegas. The IPL. Formula One. We are living in the greatest era of escapism simply because we live in the greatest era of pain.

This pain is not always personal. It's not just about you and me and those who we love. You see it in the eyes of the urchin who comes begging to you at a street corner. She has lost her childhood, her innocence. You see it in the eyes of those who work for you at home, cooking, cleaning, washing your clothes, or taking your well groomed dogs out for a walk. Each one of them, however well you may take care of them, dreams that one day they will walk away to be their own master. You see it in the eyes of your colleagues at work, however enthusiastic they may be about what they do. The long travel to work, the pitiable condition of public transportation, the missing footpaths, the growing pollution, the problems with putting kids through school and college, the frequent confrontations over rent, power, water, tax: everything contributes to this weltschmerz. It's everywhere.

I see it in parties and film premieres too. There's something very tragic in watching middle aged men and women dressed in absurd designer togs, their hair dyed and faces botoxed, prancing around like teenagers and pretending to have a great time. There are more sad-eyed drunks and dope heads there than in the dance bars of suburban Mumbai or the glitzy discotheques of five star hotels. While the real youngsters of this generation, equally sad-eyed, shot and lonely, are racing down empty Mumbai roads late at night on rented souped up bikes trying to prove their machismo. They challenge danger because they find it tougher to challenge life. They hide their pain by escaping it. So do their parents who helplessly watch them suffer, knowing that sermons don't help.

The day we all realise this, that the rich is in as much pain as the poor, that the employer is having as tough a time as the employee, that the cop who asks you for a bribe lives as sad a life as you, the pickpocket you catch has risked being lynched because he has no other alternative means of livelihood, that the movie star you idolise is as lonely as you are, that the one who brutalises you is perhaps as brutalised by life as you are, the less we will seek to blame others for our fate. You will feel less anger against that guy in the tax office who asks you for a bribe when you realise he is still paying back, after ten years on his job, his father's debt for getting him the job. We are lucky. The Americans are consuming today what their next 13 generations will have to pay for. The Greeks will be lucky if their next generation can survive their current crisis.

We have, all of us, mortgaged our futures to pay for being around. No, I am not saying this. Ask anyone who understands economics or the environment and they will tell you this. Yet man bravely strides ahead. As we flirt with more pain, more danger, we discover more and more ways to seek gratification, more technology to flaunt, more entertainment to excite us and, most important, more dreams to chase. So we pursue new ways to earn more money, grow more food, hunt down more pleasures, seek to extend our life spans. British scientists recently declared that by 2050 we will find a way to overcome mortality.

This is the miracle of our times. Even as most things go wrong, man's ingenuity to seek hope and happiness keeps improving. But where we fail most is in sustaining relationships. The best companies collapse, as do the best marriages, the best rock groups, the most intense relationships because our weltschmerz makes us lonely islands of pain. That's why last week, when R.E.M broke up after 31 years, I remembered their most popular song, which became the anthem of our times. Everybody hurts. Yes, everybody hurts. And that is why we hurt each other so much.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)