Andrew Leipus in Cricinfo

Able to bowl but not throw because of shoulder pain? Or maybe you have

lost power in your throw? Have to throw side-arm? Does your whole arm go

"dead" for a few seconds after you release the ball? Or you are now

experiencing a click, crunch or clunk when you lift the arm? These are

just some of the many symptoms and behaviours that can be present in the

cricketer's shoulder and which can help clinicians diagnose what your

underlying problem might be.

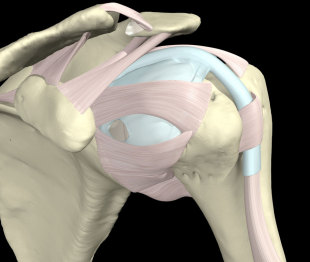

There can't be a shoulder discussion without a brief anatomy lesson. In

terms of understanding the basics, the glenohumeral joint is a shallow

ball-and-socket design, allowing a huge amount of mobility yet remaining

as stable as possible. It also has to tolerate massive torques or

rotational forces generated. Some people equate the head of the humerus

(HOH) and its relation to the scapula with a golf ball sitting on a tee,

i.e. easy to topple over. But it is actually more like trying to

balance a soccer ball on your forehead, with both the ball and the

head/body constantly moving to maintain "balance" and stop the ball from

dropping off. It is this balance between the socket joint and the

scapula position which we need to consider in the cricketer's shoulder

as it is where a lot of problems begin and where a lot of rehab

programmes fail.

As is the case with all injuries, the anatomy often lets us down by not

being able to cope with the functional demands. Some injuries develop

acutely, such as occurs with one hard throw when off balance, and some

develop over a period of time through lots of high repetition -

degenerative type injuries. The two most commonly injured structures in

cricket are the infamous rotator cuff and the glenoid labrum.

The cuff is a group of small muscles acting primarily to pull and hold

the HOH into its glenoid socket. The long head of biceps tendon assists

the rotator cuff in this role. The labrum is a circular cartilage

structure designed to "cup" or deepen this socket and provide attachment

for the biceps tendon.

An injury to the labrum results in the HOH having excess translatory

motion and not staying centred in the glenoid. The cuff then has to work

harder to compensate for this structural instability. This translation

often results in a "clunky" shoulder or one which goes "dead" when

called upon to throw at pace. Anil Kumble's shoulder had a damaged

labrum due to his high-arm legspin action. Years of repetitive stress

had detached his labrum from the glenoid, resulting in the need for

surgery. He's not alone. Muttiah Muralitharan and Shane Warne also had

shoulder surgeries in their careers. And it's not just spin bowling, as

many labral compression injuries occur during fielding when diving onto

an outstretched arm.

Injury to the cuff, however, also results in a dynamic instability,

whereby the HOH is again not held centred, and subsequently over time

stresses both the labrum and cuff. Impingement is a common term used to

describe a narrowing of the space in the shoulder that can result from

this loss of centering. The cuff doesn't actually need to be injured for

this to occur - repetitive throwing can tighten the posterior cuff

muscles and effectively "squeeze" the HOH out of its normal centre of

rotation in the glenoid. It really is a vicious circle and cricketers

compound any underlying dysfunction by the repetitive nature of the

game. They might not throw much in a match but when they do it is

usually with great speed. The bulk of the throwing volume occurs during

their practice sessions.

And when talking about shoulder mechanics we need to also understand

critical role of the scapula. In order to ensure that the HOH remains

remain centred in the glenoid, the scapula must slide and rotate

appropriately around the chest wall (that soccer ball example). Any

dysfunction in scapula movement is typically evidenced by a "winging"

motion when the arm is elevated or by observing the posture of the upper

back. Whether the winging comes before the injury or as a consequence

is hotly debated. Either way it needs to function properly. And to

complicate things even further, the thoracic spine also needs to be able

to extend and rotate fully to allow the scapula to move. Kyphotic or

slouched upper backs are terrible for allowing the arm to reach full

elevation and is a big contributor to shoulder problems.

It should be clear that in order for a cricketer's shoulder to be

pain-free, there needs to be a lot of dynamic strength and mobility of

the upper trunk and shoulder girdle. But throwing technique is equally

critical to both performance and injury prevention. Studies have shown

that the shoulder itself contributes only 25% to the release speed of

the ball. To impart this 25%, the angular velocity of the joint can

reach 7000 degrees per second. However, what is interesting is that a

whopping 50% is contributed by the hips and trunk when the player is in a

good position for the throw (allowing for a coordinated weight

transfer). But when off-balance and shying at the stumps, as often

occurs within the 30-yard circle, the shoulder alone can be called upon

to produce more than its usual load. Thus it is important to remember

that throwing should be considered as a whole body skill.

|

|||

Often a player will be able to bowl without experiencing symptoms, but

will struggle to throw. In these cases, it is common to find pathology

involving the long head of biceps or where it anchors superiorly onto

the labrum. The latter is also commonly known as a SLAP lesion. In the

transition from the cocking to acceleration phase of throwing, the

shoulder is forcefully externally rotated. The biceps is significantly

involved in stabilising the HOH at this point and often pulls so hard

that it peels the labrum off the glenoid, giving symptoms of pain and

instability. The overhead bowling action, however, does not put the

shoulder into extremes of external rotation and hence symptoms do not

usually occur. If pain is experienced during the release phase of

throwing then there is a good chance that technique is again at fault.

In order to decelerate the arm after the ball is released, the trunk and

arm need to "follow through", using the big trunk muscles and weight

shift towards the target. Failure to do this results in a massive

eccentric load on the biceps tendon, also potentially tugging on its

anchor on the glenoid. Throwing side-arm to avoid extremes of external

rotation and pain is a common sign that all is not well internally.

As you can see, an injury to the shoulder is not a simple problem. And

there are many other types of pathology found. It requires thorough

assessment and management of a host of potential contributing factors

which are mostly modifiable when identified. And whilst a lot can go

wrong in a cricketer's shoulder, there is a lot that can be done to make

sure it stays strong and healthy. Because prevention is always better

than surgery in terms of outcomes, next week I'll discuss some shoulder

training and injury prevention tips used by elite cricketers.