'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label practice. Show all posts

Showing posts with label practice. Show all posts

Monday, 12 February 2024

Saturday, 25 March 2023

Monday, 12 September 2022

Sunday, 25 April 2021

Saturday, 4 July 2020

After Wirecard: is it time to audit the auditors?

The industry’s failure to spot holes in the accounts of several collapsed companies has led to clamour for reform writes Jonathan Ford and Tabby Kinder in The FT

At the end of 2003, the Italian dairy company Parmalat descended into bankruptcy in an eye-catchingly abrupt manner. A routine bank reconciliation revealed that €3.9bn of cash which Parmalat was supposed to have at Bank of America did not actually exist.

At the end of 2003, the Italian dairy company Parmalat descended into bankruptcy in an eye-catchingly abrupt manner. A routine bank reconciliation revealed that €3.9bn of cash which Parmalat was supposed to have at Bank of America did not actually exist.

The scam that emerged duly blew apart one of Italy’s best-known entrepreneurial companies, and sent its founder, Calisto Tanzi, to prison for fraud. Dubbed Europe’s Enron, it humiliated two large auditing firms, Deloitte and Grant Thornton, and ended up costing the former $149m in damages.

Yet it rested on an apparently simple deception: the reconciliation letter on which the auditors were relying had been forged.

There were shades of Parmalat’s collapse again last week when, nearly two decades later, another fast-growing European entrepreneurial company blew up in strikingly similar circumstances.

After years of public questions about the reliability of its accounts, primarily from the FT, the German electronic payments giant, Wirecard, was forced to admit to a massive hole in its balance sheet.

Rattled by the failure of an independent probe by KPMG to verify transactions underpinning “the lion’s share” of its reported profits between 2016 and 2018, and unable to publish its results due to issues eventually raised by its longstanding auditors EY, Wirecard finally capitulated. It announced that purported €1.9bn cash balances at banks in the Philippines probably did “not exist” and parted company with its chief executive Markus Braun. Evidence relied on by EY had been bogus.

It remains unclear exactly how the crucial confirmation slipped through the cracks. According to one EY partner: “The general view internally is that confirming historic cash balances is auditing 101, and [that] ordinary auditing processes were followed, including third party verification, in which case the fraud was sophisticated in its use of false documents.”

Others, however, take a less charitable view of such slip-ups, especially when, as with both Wirecard and Parmalat, they were preceded by so many questions about the reliability of the figures.

“The integrity of the cash account [which records cash and should reconcile to all the other items in the accounts] is totally central to the whole system of double-entry bookkeeping,” says Karthik Ramanna, professor of business and public policy at Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government. “If there is no integrity to the cash account, then the whole system is just a joke.”

Shareholder support

Wirecard’s collapse is the latest in a wave of accounting scandals that has swept through the corporate world, including UK outsourcing group Carillion and Abu Dhabi-based hospital group NMC Health, as well as alleged frauds at the mini-bond firm London Capital & Finance (LCF) and the café chain Patisserie Valerie.

Many fear a further surge as the Covid-19 lockdown washes away those companies with weakened balance sheets or business models in the coming months.

Questions about “softball” auditing have dogged many recent high-profile insolvencies. Carillion’s enthusiasm for buying companies with few tangible assets for high prices led it to build up £1.5bn of goodwill on its balance sheet. Despite vast losses at some of those subsidiaries, it had written down the value of just £134m of that goodwill when the whole edifice caved in.

Similar questions hang over LCF, where close reading of the notes in the last accounts it published show how the estimated fair value of its liabilities far exceeded that of its assets in 2017, making it technically insolvent roughly 18 months before it collapsed taking with it more than £200m of savers’ cash. Yet EY gave the accounts a clean bill of health.

Such cases have raised concerns about the independence of auditors, and their willingness to challenge the wishes of management at the client, who are often driven by their own desire for self-enrichment or survival.

“It’s so important if you want to keep the relationship to have a rapport with the finance director,” says a financier who once worked at a Big Four auditing firm. “It is basically sometimes easier to swallow what you are told.”

It is a problem that has deepened with the adoption of modern accounting standards. Over the past three decades, these have progressively dismantled the traditional system of historical cost accounting with its emphasis on the verifiability of evidence and using prudent judgment, replacing it with one based on the idea that the primary purpose of accounts is to present information that is “useful to users”.

This process has allowed managers to pull forward anticipated profits and unrealised gains, and write them up as today’s surpluses. Many company bonus schemes depend on the delivery of the “right” accounting numbers.

In theory, shareholders are supposed to provide a check on the influence of self-interested bosses. They choose the auditors and set the terms of the engagement. But in practice, investors tend not to assert themselves in the relationship. Scandals rarely lead to the ejection of auditors.

So after UK telecoms group BT announced a £530m writedown in 2017 because of accounting misstatements at its Italian business, the auditors, PwC, were not sanctioned by investors. Far from it, the firm was reappointed with more than 75 per cent support. And when EY came up for re-election at Wirecard in the summer of 2018, despite rumblings about the numbers, it was voted back by more than 99 per cent.

Tight budgets and timetables

It is not only an auditor’s desire for an easy life that can drain audits of that all important culture of challenge. There are practical issues too. Tight budgets and timetables limit the scope for investigation.

Audit fees in Europe are far below those in the US. Audits of Russell 3000 index companies in the US cost 0.39 per cent of company turnover on average. Those in Europe average just 0.13 per cent, while for German companies it is a feeble 0.09 per cent.

With fees low, auditing teams are often stretched thin, with only limited support from a partner out of a desire to limit costs and maximise the number of audits done. Audit is traditionally the junior partner in a big accountancy firm, with around four-fifths of the Big Four’s profits coming from the non-audit consultancy side.

Take the last audit of BHS under the ownership of Philip Green, who sold the failing UK retailer to a little known entrepreneur, Dominic Chappell, in 2015. The chain subsequently collapsed the following year.

The PwC partner, Steve Denison, recorded only two hours of work auditing the financial statements. The number two, an auditor with just one year’s post-qualification experience, recorded 29.25 hours, and the more junior team members 114.6 hours. Mr Denison was later fined for misconduct and effectively banned by the audit regulator.

According to Tim Bush, head of governance and financial analysis at the Pensions & Investment Research Consultants, a shareholder advisory group, this reliance on juniors tends to result in “box checking” rather than an investigative approach to audit processes. “Audit teams are less likely to have a feel for the company’s business model,” he says.

This in turn can open the door to abuse. Scams often hinge on faith in some implausible business activity. Parmalat’s €3.9bn cash pile, for instance, was supposed to have come from selling milk powder to Cuba. But an analysis of the volumes claimed suggested that if the company’s numbers were accurate, each of the island’s inhabitants would have needed to be consuming 60 gallons a year.

As the author Richard Brooks noted in his book The Bean Counters: “It shouldn’t have been difficult for a half-competent audit firm to spot.”

No ‘golden age’

The academic Prem Sikka rejects the idea that auditing has gone downhill in the past few decades. “Go back into history and you will find there was never a golden age,” he says.

He argues that most of the weaknesses are of longstanding vintage, and are down to a lack of accountability. “On the audit side, there is no transparency. You have no idea as a reader of accounts how much time the auditors spent on the task and whether that was reasonable,” says the professor of accounting at the University of Sheffield.

While there are signs that the UK regulator is getting tougher, it is down to shareholders to provide stronger governance, Prof Sikka says. If they won’t do it, the government should consider setting up a state agency to commission audits of firms and set fees. “It wouldn’t have to be everyone. You could just do large companies and banks.”

Britain has recently been through a comprehensive review of audit, including how it is regulated and competition in the market, plus a review by the businessman Donald Brydon of its purpose. This devoted many pages to establishing it as a distinct new profession and coming up with new statements to include in already groaning company reports.

Far from creating new tasks, many observers think that audit should reconnect with its original purpose. This is to assure investors that companies’ capital is not being abused by over-optimistic or fraudulent managers. “At their heart, audits are about protecting capital, and thereby ensuring responsible stewardship of capital,” says Natasha Landell-Mills, head of stewardship at the asset manager Sarasin & Partners.

Yet modern accounting practice has made audits more complicated while watering down the legal requirement to exercise the judgment needed to ensure the numbers are “true and fair”. Despite the endless mushrooming of numbers, it is no easier to know if the capital is really present and can thus justify the payment of dividends and bonuses.

Michael Izza, chief executive of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales says auditors need a “renewed focus on internal controls, going concern and fraud. The vast majority of business failures are not the fault of the auditor, but when audit quality is a contributory factor, the problem generally involves these three fundamental areas.”

Mr Bush thinks a radical simplification is in order. “Without clarity there is never going to be proper accountability,” he says. “What we have is a recipe for weak auditing, and ever more Wirecards and Parmalats. In the extreme it facilitates Ponzi schemes. Stay on that route and it won’t be long before you come unstuck.”

Wednesday, 3 July 2019

Sunday, 25 November 2018

Saturday, 6 January 2018

Cleaning is a good meditation practice

Shoukei Matsumoto in The Guardian

Mental health counsellors often recommend that clients clean their home environments every day. Dirt and squalor can be symptoms of unhappiness or illness. But cleanliness is not only about mental health. It is the most basic practice that all forms of Japanese Buddhism have in common. In Japanese Buddhism, it is said that what you must do in the pursuit of your spirituality is clean, clean, clean. This is because the practice of cleaning is powerful.

Of course, as a monk who is dedicated to spiritual life, I recommend Buddhist concepts and practices. But you don’t have to convert to a new religion to learn from it. Many people’s associations with the word “religion” may include a set of rules to regulate people’s values and actions; the creation of an irrational transcendent entity; or the idea of a crutch for people who cannot think for themselves. In my view, though, a respectable religion does not exist to bind one’s values or actions. It is there to free people from the systems and standards that order society. In Japanese characters, the word “freedom” is written as “caused by oneself”.

Cleaning practice is not a tool but a purpose in itself

Cleaning practice, by which I mean the routines whereby we sweep, wipe, polish, wash and tidy, is one step on this path towards inner peace. In Japanese Buddhism, we don’t separate a self from its environment, and cleaning expresses our respect for and sense of wholeness with the world that surrounds us.

You can see the presence of nature in the Japanese traditions of sado (tea ceremonies) or kado (flower arranging), which were both originally born from Buddhism. But the idea of “nature” in Japan has been strongly influenced by western culture. Pronounced “shizen”, the characters reflect a human-centred version of the world in which humans stand at the top of a hierarchy as the agent or messenger of the creator.

But there is another sense of “nature” derived from ancient Japanese. Pronounced “jinen”, the same characters once meant “let it go” or “it is as it is” – a definition much closer to Buddhist philosophy, with its links to animism and the worship of nature.

After Buddhism and the other philosophies were introduced to the Japanese people, they began to see nature not only in humans, but also in all sentient beings, and even in mountains, rivers, plants and trees. This view of nature persists in modern Japanese culture – for example in Pokémon’s characters or Studio Ghibli films such as Arrietty, with their environmentalist messages. As a result, even when we pronounce the characters for nature as “shizen”, the term still carries with it the Japanese idea that humans are not excluded from nature, but are part of it.

Buddhism says the notion that you have your own personality is an illusion that your ego creates – and cleaning is a means to let go of this. The characters for “human being” in Japanese mean “person” and “between”. Human being is “a person in between”. Thus, you as a human being only exist through your relations with others – people such as friends, colleagues and family. You as a person have some particular words, facial expressions and behaviours, but these arise only through your interaction and connections with other people. This is the Buddhist concept “en” or interdependence.

Buddhist cleaning practice provides each of us with an opportunity to understand this concept. You don’t have to acquire special techniques, hire a professional cleaning consultant, or perform the special rituals used by senior monks.

The basics are very simple. Sweep from the top to the bottom of your home, wipe along the stream of objects and handle everything with care. After you start cleaning your home, you can extend cleaning practice to other things, including your body. How you can apply cleaning practice to your mind is a question I want to leave unanswered, but if you practise cleaning, cleaning and more cleaning, you will eventually know that you have been cleaning your inner world along with the outer one.

Of course Japanese temples sometimes employ cleaners when they are short of hands. But Buddhist monks also clean by themselves. This is because the cleaning practice is not a tool but a purpose in itself. Would you outsource your meditation practice to others?

As with meditation practice, there is no endpoint of the cleaning practice. Right after I am satisfied with the cleanliness of the garden I have swept, fallen leaves and dust begin to accumulate. Similarly, right after I feel peaceful with my ego-less mindfulness, anger or anxiety begin once again to emerge in my mind. The ego endlessly arises in my mind, so I keep cleaning for my inner peace. No cleaning, no life.

Mental health counsellors often recommend that clients clean their home environments every day. Dirt and squalor can be symptoms of unhappiness or illness. But cleanliness is not only about mental health. It is the most basic practice that all forms of Japanese Buddhism have in common. In Japanese Buddhism, it is said that what you must do in the pursuit of your spirituality is clean, clean, clean. This is because the practice of cleaning is powerful.

Of course, as a monk who is dedicated to spiritual life, I recommend Buddhist concepts and practices. But you don’t have to convert to a new religion to learn from it. Many people’s associations with the word “religion” may include a set of rules to regulate people’s values and actions; the creation of an irrational transcendent entity; or the idea of a crutch for people who cannot think for themselves. In my view, though, a respectable religion does not exist to bind one’s values or actions. It is there to free people from the systems and standards that order society. In Japanese characters, the word “freedom” is written as “caused by oneself”.

Cleaning practice is not a tool but a purpose in itself

Cleaning practice, by which I mean the routines whereby we sweep, wipe, polish, wash and tidy, is one step on this path towards inner peace. In Japanese Buddhism, we don’t separate a self from its environment, and cleaning expresses our respect for and sense of wholeness with the world that surrounds us.

You can see the presence of nature in the Japanese traditions of sado (tea ceremonies) or kado (flower arranging), which were both originally born from Buddhism. But the idea of “nature” in Japan has been strongly influenced by western culture. Pronounced “shizen”, the characters reflect a human-centred version of the world in which humans stand at the top of a hierarchy as the agent or messenger of the creator.

But there is another sense of “nature” derived from ancient Japanese. Pronounced “jinen”, the same characters once meant “let it go” or “it is as it is” – a definition much closer to Buddhist philosophy, with its links to animism and the worship of nature.

After Buddhism and the other philosophies were introduced to the Japanese people, they began to see nature not only in humans, but also in all sentient beings, and even in mountains, rivers, plants and trees. This view of nature persists in modern Japanese culture – for example in Pokémon’s characters or Studio Ghibli films such as Arrietty, with their environmentalist messages. As a result, even when we pronounce the characters for nature as “shizen”, the term still carries with it the Japanese idea that humans are not excluded from nature, but are part of it.

Buddhism says the notion that you have your own personality is an illusion that your ego creates – and cleaning is a means to let go of this. The characters for “human being” in Japanese mean “person” and “between”. Human being is “a person in between”. Thus, you as a human being only exist through your relations with others – people such as friends, colleagues and family. You as a person have some particular words, facial expressions and behaviours, but these arise only through your interaction and connections with other people. This is the Buddhist concept “en” or interdependence.

Buddhist cleaning practice provides each of us with an opportunity to understand this concept. You don’t have to acquire special techniques, hire a professional cleaning consultant, or perform the special rituals used by senior monks.

The basics are very simple. Sweep from the top to the bottom of your home, wipe along the stream of objects and handle everything with care. After you start cleaning your home, you can extend cleaning practice to other things, including your body. How you can apply cleaning practice to your mind is a question I want to leave unanswered, but if you practise cleaning, cleaning and more cleaning, you will eventually know that you have been cleaning your inner world along with the outer one.

Of course Japanese temples sometimes employ cleaners when they are short of hands. But Buddhist monks also clean by themselves. This is because the cleaning practice is not a tool but a purpose in itself. Would you outsource your meditation practice to others?

As with meditation practice, there is no endpoint of the cleaning practice. Right after I am satisfied with the cleanliness of the garden I have swept, fallen leaves and dust begin to accumulate. Similarly, right after I feel peaceful with my ego-less mindfulness, anger or anxiety begin once again to emerge in my mind. The ego endlessly arises in my mind, so I keep cleaning for my inner peace. No cleaning, no life.

Monday, 6 March 2017

Turn, flight and parabola separate a genuine spinner from an ordinary one

Nagraj Gollapudi in Cricinfo

Rajinder Goel, Padmakar Shivalkar and V V Kumar, three spinners who traumatised batsmen from the 1960s to the late-1980s, will be honoured by the BCCI on March 8 for their services to Indian cricket. Goel and Shivalkar, both left-arm spinners, will be given the CK Nayudu Lifetime Achievement Award. Kumar, a legspinner who played two Tests for India, will be given a special award for his "yeoman" service

In the following interview, the three talk about learning the basics of spin, their favourite practitioners of the art, and what has changed since their time.

What makes a good spinner?

Rajinder Goel - Hard work, practice, and some intellect on how to play the batsman - these are mandatory. Without practice you will not be able to master line and length, which are key to defeat the batsman.

Padmakar Shivalkar - Your basics of line and length need to be in place. The delivery needs to have a loop. This loop, which we used to call flight, needs to be a constant. Over the years, you increase this loop, adjust it. You lock the batsman first and then spread the web - he gets trapped steadily. But these things are not learned easily. It takes years and years of work before you reach the top level.

VV Kumar - There are many components involved. A spinner has to spend a lot of time in the nets. You can possibly become a spinner by participating in a practice session for a couple of hours. But you cannot become a real good spinner. A spinner must first understand what exactly is spinning the ball. A real spinner should possess the following qualities, otherwise he can only be termed a roller.

The number one thing is to have revolutions on the ball. Then you overspin your off- or legbreaks. There are two types when it comes to imparting spin: overspin and sidespin. A ball that is sidespun is mostly delivered with an improper action and is against the fundamentals of spin bowling. A real spinner will overspin his off- or legbreak, which, when it hits the ground, will have bounce, a lot of drift and turn. A sidespun delivery will only break - it will take a deviation. An overspun delivery will spin, bounce and then turn in or away sharply.

Then we come to control. The spinner needs to have control over the flight, the parabola. Flight does not mean just throwing the ball in the air. Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of breaking the ball to exhibit the parabola or dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back. But if the flight does not land properly, it can end up in a full toss.

The concept of a good spinner also includes bowling from over the wicket to both the right- and left-handed batsman. The present trend is for spinners to come round the wicket, which is negative and indicates you do not want to get punished. A spin bowler will have to give runs to get a wicket, but he should not gift it.

A spinner is not complete without mastering line and length. He must utilise the field to make the batsman play such strokes that will end up in a catch. That depends on the line he is bowling, his ability to flight the ball, to make the batsman come forward, or spin the ball to such an extent that the batsman probably tries to cut, pull, drive or edge. That is the culmination of a spinner planning and executing the downfall of a good batsman. For all this to happen, all the above fundamentals are compulsory. Turn, flight and parabola separate a genuine spinner from an ordinary spinner.

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty Images

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty Images

Did you have a mentor who helped you become a good spinner?

Goel - Lala Amarnath. It was 1957. I was in grade ten. I was part of the all-India schools camp in Chail in Himachal Pradesh. He taught me the basics of spin bowling. The most important thing he taught me was to come across the umpire and bowl from close to the stumps. He said with that kind of action I would be able to use the crease well and could play with the angles and the length easily.

Kumar - I am self-taught, and I say that without any arrogance. I started practising by spinning a golf ball against the wall. It would come back in a different direction. The ten-year-old in me got curious from that day about how that happened. I started reading good books by former players, like Eric Hollies, Clarrie Grimmett and Bill O' Reilly. Of course, my first book was The Art of Cricket by Don Bradman. That is how I equipped myself with the knowledge and put it in practice with a ball in hand.

Shivalkar - It was my whole team at Shivaji Park Gymkhana who made me what I became. If there was a bad ball, and there were many when I was a youngster in 1960-61, I learned a lot from what senior players said, their gestures, their body language. [Vijay] Manjrekar, [Manohar] Hardikar, [Chandrakant] Patankar would tell me: "Shivalkar, watch how he [the batsman] is playing. Tie him up." "Kay kartos? Changli bowling tak [What are you doing? Bowl well]," they would say, at times widening their eyes, at times raising their voice. I would obey that, but I would tell them I was trying to get the batsman out. You cannot always prevail over the batsman, but I cannot ever give up, I would tell myself.

What was your favourite mode of dismissal?

Goel - My strength was to attack the pads. I would maintain the leg-and-middle line. Batsmen who attempted to sweep or tried to play against the spin, I had a good chance of getting them caught in the close-in positions, or even get them bowled. I used to get bat-pad catches frequently, so I would call that my favourite.

"Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of the breaking the ball to exhibit the dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - My best way of getting a batsman out was to make him play forward and lure him to drive. Whether it was a quicker, flighted or flat delivery, I always tried to get the batsman on the front foot. Plenty of my wickets were caught at short leg, fine leg and short extra cover - that shows the batsman was going for the drives. I would not allow him to cut or pull. I would get these wickets through well-spun legbreaks, googlies, offspinners. You have to be very clear about your control and accuracy, otherwise you will be hit all over the place. You should always dominate the batsman. You have to play on his mind. Make him think it is a legbreak and instead he is beaten by flight and dip.

Shivalkar - I used to enjoy getting the batsman stumped. With my command over the loop, batsmen would step out of the crease and get trapped, beaten and stumped.

Tell us about one of your most prized wickets.

Goel - I was playing for State Bank of India against ACC (Associated Cement Companies) in the Moin-ud-Dowlah Gold Cup semi-finals in 1965 in Hyderabad. Polly saab [Polly Umrigar] was playing for ACC. He was a very good player of spin. He was playing well till our captain [Sharad] Diwadkar threw the second new ball to me. I got it to spin immediately and rapped Polly saab on the pads as he attempted to play me on the back foot. It was difficult to force a batsman like him to miss a ball, so it was a wicket I enjoyed taking.

Kumar - Let me talk about the wicket I did not get but one I cherish to this day. I was part of the South Zone team playing against the West Indians in January 1959 at Central College Ground in Bangalore. Garry Sobers came in to bat after I had got Conrad Hunte. I was thrilled and nervous to bowl to the best batsman. Gopi [CD Gopinath] told me to bowl as if I was bowling in any domestic match and not get bothered by the gifted fellow called Sobers.

The first ball was a legbreak, pitched outside off stump. Sobers moved across to pull me. Second ball was a topspinner, a full-length ball on the off stump. He went on the leg side and pushed it past point for four. The third ball was quickish, which he defended. Next, I delivered a googly on the middle stump. Garry came outside to drive, but the ball took the parabola and dipped. He checked his stroke and in the process sent me a simple, straightforward return catch. The ball jumped out of my hands. I put my hands on my head.

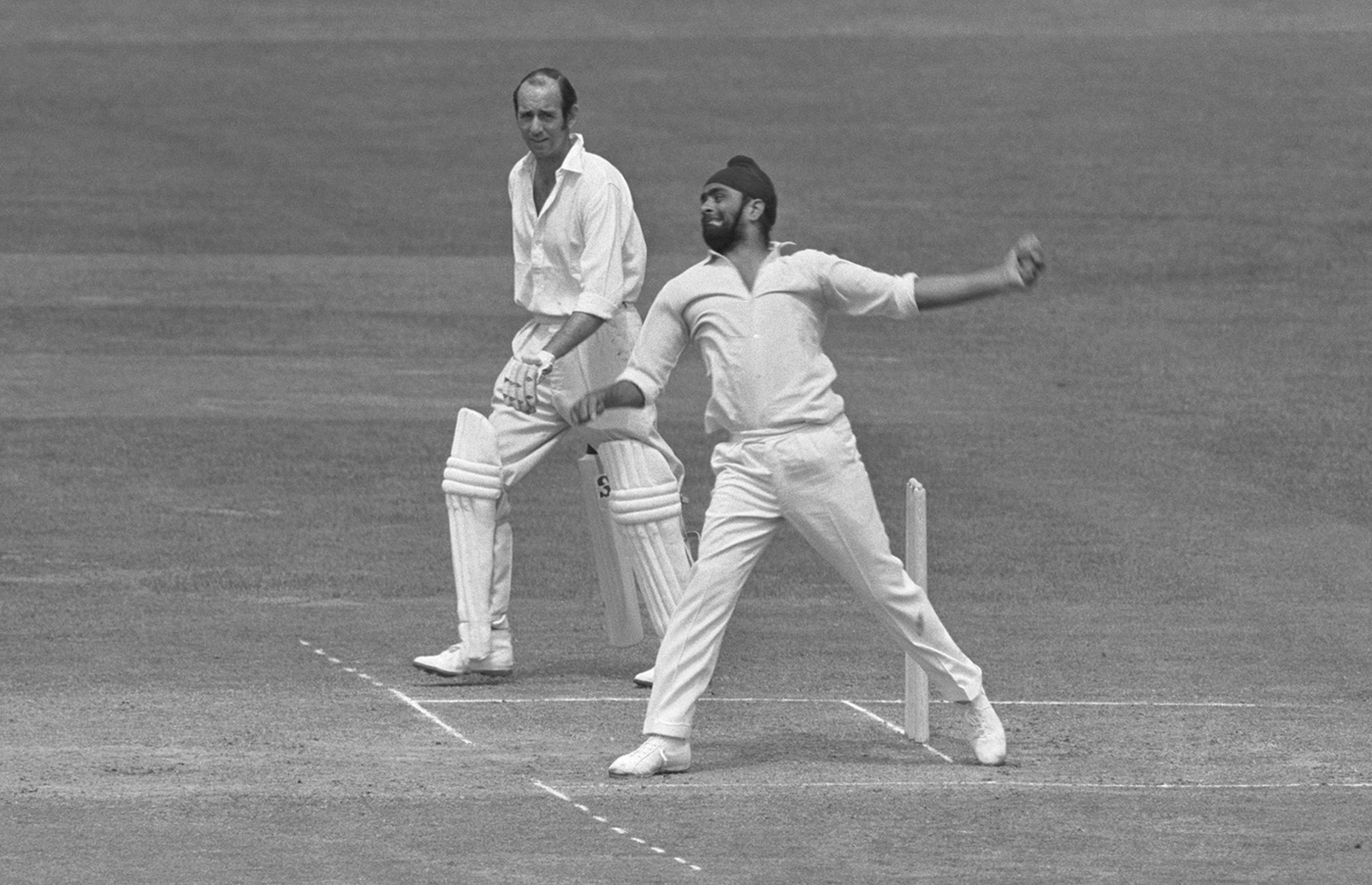

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA Photos

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA Photos

Who was the best spinner you saw bowl?

Goel - There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi. His high-arm action, the control he had over the ball, the way he would outguess a batsman - I loved Bedi's bowling. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches.

Kumar- I will call him my idol. I have not seen anybody else like Subhash Gupte, a brilliant legspinner. I have never seen anybody else reach his standards, including Shane Warne. Sobers himself said he was the best spinner he had ever played. In those days he operated on pitches that were absolutely dead tracks. It was Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him! That is why he is the greatest spinner I have seen.

Who was the best player of spin you bowled against?

Goel - Ramesh Saxena [Delhi and Bihar] and Vijay Bhosle [Bombay] were two good players of spin. Saxena would never allow the ball to spin. He would reach out to kill the spin. Bhosle was similar, and used to be aggressive against spin.

Kumar - Vijay Manjrekar was probably the best player of spin I encountered. What made him great was the time he had at his disposal to play the ball so late. And by doing that he made the spinner look mediocre.

"No one offers the loop anymore. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive"

PADMAKAR SHIVALKAR

Shivalkar - [Gundappa] Viswanath. He could change his shot at the last moment. Once, I remember I thought I had him. He was getting ready to cut me on the off stump, but the ball dipped and turned into him. I nearly said "Oooh", thinking he would be either lbw or bowled. But Vishy had amazing bat speed and he managed to get the bat down and the edge whisked past fine leg. He ran two and then looked at me and smiled. He had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrekar called him an artist. Vishy was a jaadugar [magician].

What has changed in spin bowling since the emergence of T20?

Goel - Earlier, we would flight the ball and not get bothered even if we got hit for four. We used to think of getting the batsman out. Now spinners think about arresting the runs. That is one big difference, which is an influence of T20.

Kumar - The three fundamentals I mentioned earlier do not exist in T20 cricket. Spinners are trying to bowl quick and waiting for the batsman to make the mistake. The spinner is not trying to make the batsman commit a mistake by sticking to the fundamentals. In four overs you cannot plan and execute.

Shivalkar - They have become defensive. No one offers the loop anymore. The difference has been brought upon by the bowlers themselves. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive. At times you should deliver from behind the popping crease, but you cannot allow the batsmen to guess that. That allows you more time for the delivery to land, for your flight to dip. The batsman is put in a fix. I have trapped batsmen that way.

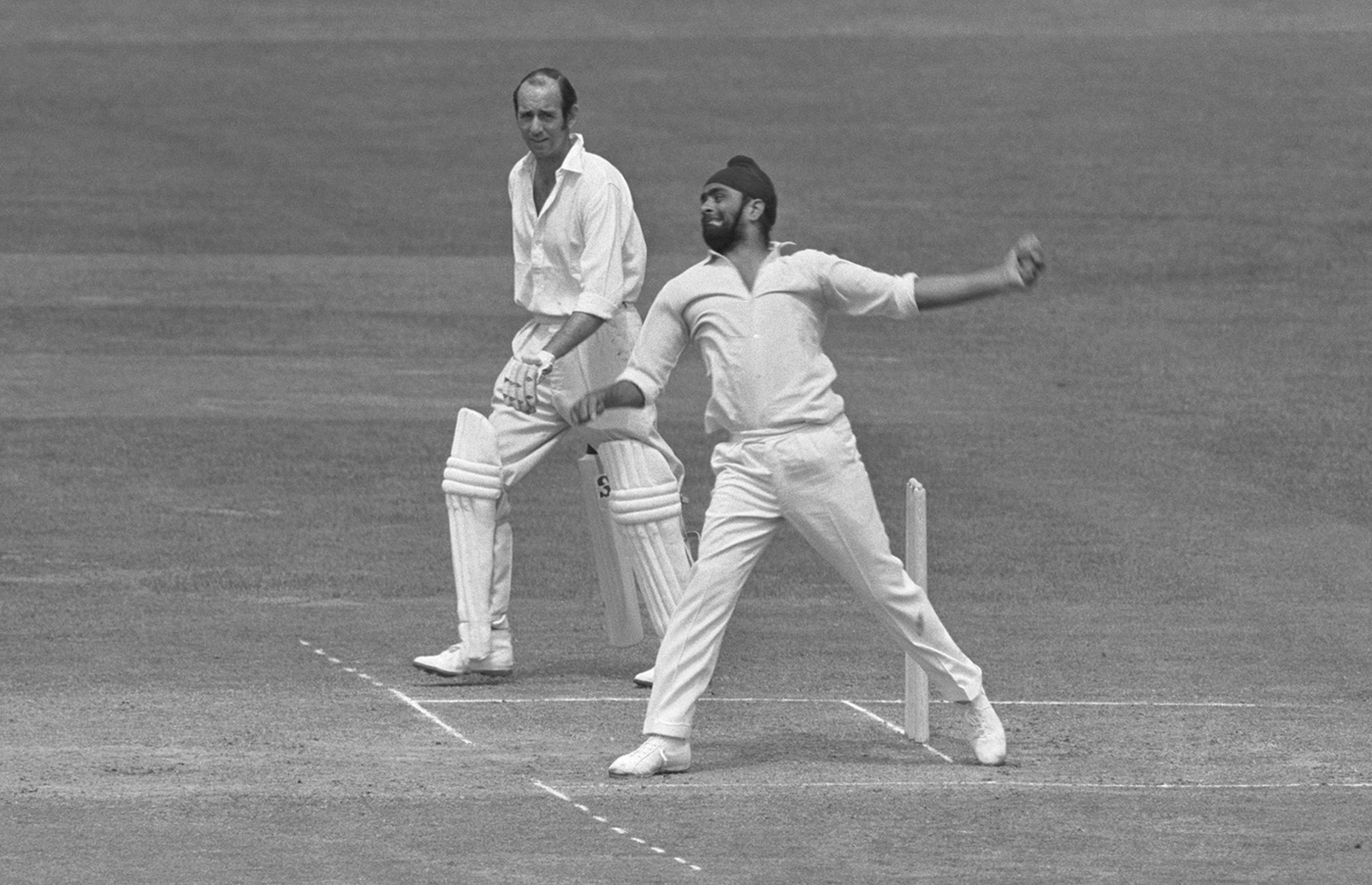

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFP

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFP

We were playing for Tatas against Indian Oil [Corporation] in the Times Shield. Dilip Vengsarkar was standing at short extra cover. One batsman stepped out, trying to drive me, but Dilip took an easy catch. A couple of overs later he took another catch at the same spot. A third batsman departed in similar fashion in quick succession. Then a lower-order batsman played straight to Dilip, who dropped the catch as he was laughing at the ease with which I was getting the wickets. "Paddy, in my life I have never taken such easy catches," Dilip said, chuckling. The batsmen were not aware I was bowling from behind the crease. If they had noticed, they might have blocked it.

Rajinder Goel, Padmakar Shivalkar and V V Kumar, three spinners who traumatised batsmen from the 1960s to the late-1980s, will be honoured by the BCCI on March 8 for their services to Indian cricket. Goel and Shivalkar, both left-arm spinners, will be given the CK Nayudu Lifetime Achievement Award. Kumar, a legspinner who played two Tests for India, will be given a special award for his "yeoman" service

In the following interview, the three talk about learning the basics of spin, their favourite practitioners of the art, and what has changed since their time.

What makes a good spinner?

Rajinder Goel - Hard work, practice, and some intellect on how to play the batsman - these are mandatory. Without practice you will not be able to master line and length, which are key to defeat the batsman.

Padmakar Shivalkar - Your basics of line and length need to be in place. The delivery needs to have a loop. This loop, which we used to call flight, needs to be a constant. Over the years, you increase this loop, adjust it. You lock the batsman first and then spread the web - he gets trapped steadily. But these things are not learned easily. It takes years and years of work before you reach the top level.

VV Kumar - There are many components involved. A spinner has to spend a lot of time in the nets. You can possibly become a spinner by participating in a practice session for a couple of hours. But you cannot become a real good spinner. A spinner must first understand what exactly is spinning the ball. A real spinner should possess the following qualities, otherwise he can only be termed a roller.

The number one thing is to have revolutions on the ball. Then you overspin your off- or legbreaks. There are two types when it comes to imparting spin: overspin and sidespin. A ball that is sidespun is mostly delivered with an improper action and is against the fundamentals of spin bowling. A real spinner will overspin his off- or legbreak, which, when it hits the ground, will have bounce, a lot of drift and turn. A sidespun delivery will only break - it will take a deviation. An overspun delivery will spin, bounce and then turn in or away sharply.

Then we come to control. The spinner needs to have control over the flight, the parabola. Flight does not mean just throwing the ball in the air. Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of breaking the ball to exhibit the parabola or dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back. But if the flight does not land properly, it can end up in a full toss.

The concept of a good spinner also includes bowling from over the wicket to both the right- and left-handed batsman. The present trend is for spinners to come round the wicket, which is negative and indicates you do not want to get punished. A spin bowler will have to give runs to get a wicket, but he should not gift it.

A spinner is not complete without mastering line and length. He must utilise the field to make the batsman play such strokes that will end up in a catch. That depends on the line he is bowling, his ability to flight the ball, to make the batsman come forward, or spin the ball to such an extent that the batsman probably tries to cut, pull, drive or edge. That is the culmination of a spinner planning and executing the downfall of a good batsman. For all this to happen, all the above fundamentals are compulsory. Turn, flight and parabola separate a genuine spinner from an ordinary spinner.

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty Images

Shivalkar: "Vishy had amazing bat speed... he had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrkear called him an artist" © Getty ImagesDid you have a mentor who helped you become a good spinner?

Goel - Lala Amarnath. It was 1957. I was in grade ten. I was part of the all-India schools camp in Chail in Himachal Pradesh. He taught me the basics of spin bowling. The most important thing he taught me was to come across the umpire and bowl from close to the stumps. He said with that kind of action I would be able to use the crease well and could play with the angles and the length easily.

Kumar - I am self-taught, and I say that without any arrogance. I started practising by spinning a golf ball against the wall. It would come back in a different direction. The ten-year-old in me got curious from that day about how that happened. I started reading good books by former players, like Eric Hollies, Clarrie Grimmett and Bill O' Reilly. Of course, my first book was The Art of Cricket by Don Bradman. That is how I equipped myself with the knowledge and put it in practice with a ball in hand.

Shivalkar - It was my whole team at Shivaji Park Gymkhana who made me what I became. If there was a bad ball, and there were many when I was a youngster in 1960-61, I learned a lot from what senior players said, their gestures, their body language. [Vijay] Manjrekar, [Manohar] Hardikar, [Chandrakant] Patankar would tell me: "Shivalkar, watch how he [the batsman] is playing. Tie him up." "Kay kartos? Changli bowling tak [What are you doing? Bowl well]," they would say, at times widening their eyes, at times raising their voice. I would obey that, but I would tell them I was trying to get the batsman out. You cannot always prevail over the batsman, but I cannot ever give up, I would tell myself.

What was your favourite mode of dismissal?

Goel - My strength was to attack the pads. I would maintain the leg-and-middle line. Batsmen who attempted to sweep or tried to play against the spin, I had a good chance of getting them caught in the close-in positions, or even get them bowled. I used to get bat-pad catches frequently, so I would call that my favourite.

"Flight means you spin the ball in such a way that you impart revolutions to the ball with the idea of the breaking the ball to exhibit the dip. By doing that you put the batsman in two minds - whether he should come forward or stay back"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - My best way of getting a batsman out was to make him play forward and lure him to drive. Whether it was a quicker, flighted or flat delivery, I always tried to get the batsman on the front foot. Plenty of my wickets were caught at short leg, fine leg and short extra cover - that shows the batsman was going for the drives. I would not allow him to cut or pull. I would get these wickets through well-spun legbreaks, googlies, offspinners. You have to be very clear about your control and accuracy, otherwise you will be hit all over the place. You should always dominate the batsman. You have to play on his mind. Make him think it is a legbreak and instead he is beaten by flight and dip.

Shivalkar - I used to enjoy getting the batsman stumped. With my command over the loop, batsmen would step out of the crease and get trapped, beaten and stumped.

Tell us about one of your most prized wickets.

Goel - I was playing for State Bank of India against ACC (Associated Cement Companies) in the Moin-ud-Dowlah Gold Cup semi-finals in 1965 in Hyderabad. Polly saab [Polly Umrigar] was playing for ACC. He was a very good player of spin. He was playing well till our captain [Sharad] Diwadkar threw the second new ball to me. I got it to spin immediately and rapped Polly saab on the pads as he attempted to play me on the back foot. It was difficult to force a batsman like him to miss a ball, so it was a wicket I enjoyed taking.

Kumar - Let me talk about the wicket I did not get but one I cherish to this day. I was part of the South Zone team playing against the West Indians in January 1959 at Central College Ground in Bangalore. Garry Sobers came in to bat after I had got Conrad Hunte. I was thrilled and nervous to bowl to the best batsman. Gopi [CD Gopinath] told me to bowl as if I was bowling in any domestic match and not get bothered by the gifted fellow called Sobers.

The first ball was a legbreak, pitched outside off stump. Sobers moved across to pull me. Second ball was a topspinner, a full-length ball on the off stump. He went on the leg side and pushed it past point for four. The third ball was quickish, which he defended. Next, I delivered a googly on the middle stump. Garry came outside to drive, but the ball took the parabola and dipped. He checked his stroke and in the process sent me a simple, straightforward return catch. The ball jumped out of my hands. I put my hands on my head.

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA Photos

Goel: "There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi [in photo]. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches" © PA PhotosWho was the best spinner you saw bowl?

Goel - There is no better spinner than Bishan Singh Bedi. His high-arm action, the control he had over the ball, the way he would outguess a batsman - I loved Bedi's bowling. I was in awe of the flight he could impart on the ball. In contrast, I was rapid. Bedi was good on good pitches.

Kumar- I will call him my idol. I have not seen anybody else like Subhash Gupte, a brilliant legspinner. I have never seen anybody else reach his standards, including Shane Warne. Sobers himself said he was the best spinner he had ever played. In those days he operated on pitches that were absolutely dead tracks. It was Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him! That is why he is the greatest spinner I have seen.

Who was the best player of spin you bowled against?

Goel - Ramesh Saxena [Delhi and Bihar] and Vijay Bhosle [Bombay] were two good players of spin. Saxena would never allow the ball to spin. He would reach out to kill the spin. Bhosle was similar, and used to be aggressive against spin.

Kumar - Vijay Manjrekar was probably the best player of spin I encountered. What made him great was the time he had at his disposal to play the ball so late. And by doing that he made the spinner look mediocre.

"No one offers the loop anymore. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive"

PADMAKAR SHIVALKAR

Shivalkar - [Gundappa] Viswanath. He could change his shot at the last moment. Once, I remember I thought I had him. He was getting ready to cut me on the off stump, but the ball dipped and turned into him. I nearly said "Oooh", thinking he would be either lbw or bowled. But Vishy had amazing bat speed and he managed to get the bat down and the edge whisked past fine leg. He ran two and then looked at me and smiled. He had a sharp eye. [Vijay] Manjrekar called him an artist. Vishy was a jaadugar [magician].

What has changed in spin bowling since the emergence of T20?

Goel - Earlier, we would flight the ball and not get bothered even if we got hit for four. We used to think of getting the batsman out. Now spinners think about arresting the runs. That is one big difference, which is an influence of T20.

Kumar - The three fundamentals I mentioned earlier do not exist in T20 cricket. Spinners are trying to bowl quick and waiting for the batsman to make the mistake. The spinner is not trying to make the batsman commit a mistake by sticking to the fundamentals. In four overs you cannot plan and execute.

Shivalkar - They have become defensive. No one offers the loop anymore. The difference has been brought upon by the bowlers themselves. A consistent loop will always check the batsmen, in T20 too, and also get them out. But you have to be deceptive. At times you should deliver from behind the popping crease, but you cannot allow the batsmen to guess that. That allows you more time for the delivery to land, for your flight to dip. The batsman is put in a fix. I have trapped batsmen that way.

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFP

Erapalli Prasanna (left), one of India's famed spin quartet, with Padmakar Shivalkar, who took 580 first-class wickets at 19.69 but never played a Test © AFPWe were playing for Tatas against Indian Oil [Corporation] in the Times Shield. Dilip Vengsarkar was standing at short extra cover. One batsman stepped out, trying to drive me, but Dilip took an easy catch. A couple of overs later he took another catch at the same spot. A third batsman departed in similar fashion in quick succession. Then a lower-order batsman played straight to Dilip, who dropped the catch as he was laughing at the ease with which I was getting the wickets. "Paddy, in my life I have never taken such easy catches," Dilip said, chuckling. The batsmen were not aware I was bowling from behind the crease. If they had noticed, they might have blocked it.

What is the one thing you cannot teach a spinner?

Goel- Practice. Line, length and control can only be gained through a lot of hard practice. No one can teach that. Spin bowling is a natural talent. Every ball you have to think as a spinner - what you bowl, how you try and counter the strength or weakness of a batsman, read his reactions, whether he plays flight well and then I need to increase my pace, and such things. All these subtle things only come through practice.

Kumar - There is no such thing that cannot be taught.

Shivalkar - This game is a play of andaaz [style]. That andaaz can only be learned with experience.

What are the things that every spinner needs to have in his toolkit?

Goel - Firstly, you have to check where the batsman plays well, so you don't pitch it in his area. Don't feed to his strengths. You have to guess this quickly.

"It was Subhash Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him!"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - A spinner should understand what line and length is before going into a match.

Shivalkar- You have to decide that on your own. What I have, what can I do are things only a spinner needs to understand on his own. For example, a batsman cuts me. Next time he tries, I push the ball in fast, getting him caught at the wicket or bowled.

Goel- Practice. Line, length and control can only be gained through a lot of hard practice. No one can teach that. Spin bowling is a natural talent. Every ball you have to think as a spinner - what you bowl, how you try and counter the strength or weakness of a batsman, read his reactions, whether he plays flight well and then I need to increase my pace, and such things. All these subtle things only come through practice.

Kumar - There is no such thing that cannot be taught.

Shivalkar - This game is a play of andaaz [style]. That andaaz can only be learned with experience.

What are the things that every spinner needs to have in his toolkit?

Goel - Firstly, you have to check where the batsman plays well, so you don't pitch it in his area. Don't feed to his strengths. You have to guess this quickly.

"It was Subhash Gupte's ability to adjust and adapt on any kind of surface, his perseverance and the variety he had - my goodness, no one came near to him!"

VV KUMAR

Kumar - A spinner should understand what line and length is before going into a match.

Shivalkar- You have to decide that on your own. What I have, what can I do are things only a spinner needs to understand on his own. For example, a batsman cuts me. Next time he tries, I push the ball in fast, getting him caught at the wicket or bowled.

What is beautiful about spin bowling?

Goel - When the ball takes a lot of turn and then goes on to beat the bat - it is beautiful.

Kumar - A spinner has a lot of tools to befuddle the batsman with and be a nuisance to him at all times. He has plenty in his repertoire, which make him satisfying to watch as well as make spin bowling a spectacle.

Shivalkar - When you get your loop right, the best batsman gets trapped. You take satisfaction from the fact that the ball might have dipped, pitched, taken the turn, and then, probably, turned in or out to beat the batsman. You can then say "Wah". You have Vishy facing you. You assess what he is doing and accordingly set the trap.

Goel - When the ball takes a lot of turn and then goes on to beat the bat - it is beautiful.

Kumar - A spinner has a lot of tools to befuddle the batsman with and be a nuisance to him at all times. He has plenty in his repertoire, which make him satisfying to watch as well as make spin bowling a spectacle.

Shivalkar - When you get your loop right, the best batsman gets trapped. You take satisfaction from the fact that the ball might have dipped, pitched, taken the turn, and then, probably, turned in or out to beat the batsman. You can then say "Wah". You have Vishy facing you. You assess what he is doing and accordingly set the trap.

Thursday, 17 November 2016

It’s only wrong when YOU do it! The psychology of hypocrisy

Dean Burnett in The Guardian

In these times of political turmoil, aggressive online discourse, “post-truth”society and lord knows what else, one thing is hard to deny: there’s a lot of hypocrisy flying around. People regularly and angrily lambast others for doing something, while doing pretty much the exact same thing themselves.

Pundits condemning young people for being “special snowflakes” for wanting to be sheltered from controversial views in “safe spaces”, then having an apparent meltdown whenever they see anything even vaguely inconsistent with their opinions. Angry online types who condemn the BBC for “bias” while enthusiastically linking to sites that make no effort at all at neutrality. People who preach tolerance and respect but get outraged whenever anyone disputes their methods. The list goes on.

You’d think that the highest level of politics wouldn’t allow such behaviour, but no, seems more common than ever there. Wherever you find it, it’s often infuriating. Where do people get off dictating how others should behave, putting restrictions on what they can say and do that they don’t adhere to themselves? It’s wrong and immoral, and shows that they can’t be trusted.

Or does it? In the scientific sense, hypocrisy is somewhat more complicated. It can manifest in several ways, and for several reasons, and often times the people guilty of it aren’t doing it purely to be self-serving.

Sometimes timing is the difference between being called a hypocrite or a saint. Photograph: Linda Nylind for the Guardian

The nature and timing of hypocrisy

A lot of things that are labelled hypocrisy may not actually be hypocritical, and a lot of the time, things that are hypocritical are given a pass because they are consistent with the observer’s worldview.

For example, someone who urges people to give money to charity but is then found out to give nothing themselves, they’d be considered a hypocrite. But if someone is known to be something of a skinflint then starts urging people to give to charity, they may still be considered a hypocrite, but it’s also possible they’ve just had a change of heart. Changing your mind or working for redemption are regularly considered good things. Bob Cratchit didn’t stop to accuse Scrooge of being a hypocrite.

Also, people tend to react more strongly to hypocrisy when it includes criticism or negative judgement. Someone boasts about being a live music supporter but is found to never go to gigs? Hypocritical, annoying, but not really worth getting angry about. But, a right-wing politician condemns homosexuality and attacks gay rights, but is then found to be engaging in homosexual activity themselves?Appalling. People react strongly to perceived injustice, so hypocrisy like this will get them very angry and demanding retribution.

Similarly, people are far quicker to notice and call out hypocrisy when it goes against their own beliefs. A politician you oppose promotes family values but is caught having an affair? Hypocrite! Drum them out of office! But if it’s a politician you support? Gutter journalism! So he’s not perfect, give him another chance! There are more important issues to worry about etc.

Basically, people aren’t 100% rational or consistent. Value judgements are typically subjective rather than objective, so the extent and seriousness of the hypocrisy is often in the eye of the beholder. This feeds into hypocrisy in other ways too.

We have a much higher opinion of ourselves than is usually warranted. Hopefully, other people will be willing to point this out. Photograph: PeopleImages.com/Getty Images

You think you’re better than others

Humans aren’t cold logical robots, and we typically have a higher opinion of ourselves than is warranted. Most humans have a self-serving bias, where we evaluate our own abilities and performance far more highly than is actually the case. People who achieve a certain level of intellectual achievement in certain contexts can reverse this, but we mostly think overly-well of ourselves.

It’s no surprise; the brain is riddled with cognitive and memory biases that are geared towards making us feel like we’re good and decent and capable, no matter what the reality. The problem is that our judgements of other people are far more “realistic”.

In some cases, this can lead to hypocrisy. A pilot would be well within her rights to stop an untrained person from assuming control of a plane, even though she does that all the time. This isn’t hypocrisy, this is simple acknowledgement of ability. Likewise, some people may tell others to do something and not do it themselves because they genuinely think they don’t need to do it, but the other inferior people need to be told. Not very nice, granted. May even not be a conscious decision. But it’s also not deliberate hypocrisy, if you look at it that way. Not that this makes any difference to the outcome, as far as most are concerned.

Thinking one thing and doing another can cause a lot of internal distress, and you just want it to go away. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Dissonance is disturbing

Those of you who are familiar with cognitive dissonance, the process whereby a mismatch between behaviour and attitudes/beliefs causes discomfort in the brain, may wonder why this doesn’t undermine hypocritical behaviour. Surely it would prevent people from doing things they openly condemn?

Again, it depends on the situation. Often, the “I’m better than other people so it’s OK” conclusion would be enough to reconcile it. But other times, it gets more serious. Take the earlier examples of anti-gay politicians found to be engaging in homosexual acts. This comes across as immensely hypocritical so they should be experiencing serious dissonance. But it could be argued that their actions are an attempt to resolve the dissonance. You’re raised in an environment that believes homosexuality is a sin, and you end up believing this completely. Why wouldn’t you? Then you hit adolescence and it turns out you are homosexual (it’s not a choice, after all). Now you’ve got serious dissonance; beliefs that insist homosexuality is wrong combined with physical attraction to the same sex.

One way to resolve this is to double down on the anti-gay behaviour. “I can’t be gay, look how much I hate them and work against them!” Now your beliefs and behaviour are more consistent, a sort of “fake it ‘til you make it” approach. But it’s difficult to maintain, as sex is a very powerful motivator, and people often aren’t strong enough to fight it. So you end up with strident anti-gay campaigners submitting to their desires. It’s not intentional hypocrisy in a sense, and it would be easy to only pity them for their struggles if they didn’t harm anyone else.

But they do. So it isn’t.

“I could work hard to be a good person, but... why bother?” Photograph: Blend Images/REX/Shutterstock

Hypocrisy is just easier

The problem with practising what you preach, or maintaining a high moral standard, is it’s work. You tell people to give money to charity or abstain from certain indulgences, this means you have to do these things too. But what if you just said you do these things, but didn’t? You get all the benefits of people thinking you’re a good and capable person, but you don’t have to practice any restraint. It’s win-win.

Humans are prone to the principal of least effort, often known as the “path of least resistance”, which means they’ll go for whatever option requires the least work. Hypocrisy allows you to appear principled without having to be so, which is much easier than adhering to strict principles. Modern politicians seem to have grasped this fact, making big speeches about all the great things they’ll do and then never doing any of them. Given how they seldom seem to suffer any consequences for their hypocrisy being revealed (i.e. any political event of 2016), why would they stop?

There are some positives though. Some studies show that, when called out on hypocrisy, people can end up more dedicated to the beliefs and practices they only claimed to adhere to previously. So don’t be afraid to point out hypocrisy when you see it, you might be doing some good overall.

And that includes hypocrisy about things you agree with, otherwise you’ll be… well, there’s a word for that.

In these times of political turmoil, aggressive online discourse, “post-truth”society and lord knows what else, one thing is hard to deny: there’s a lot of hypocrisy flying around. People regularly and angrily lambast others for doing something, while doing pretty much the exact same thing themselves.

Pundits condemning young people for being “special snowflakes” for wanting to be sheltered from controversial views in “safe spaces”, then having an apparent meltdown whenever they see anything even vaguely inconsistent with their opinions. Angry online types who condemn the BBC for “bias” while enthusiastically linking to sites that make no effort at all at neutrality. People who preach tolerance and respect but get outraged whenever anyone disputes their methods. The list goes on.

You’d think that the highest level of politics wouldn’t allow such behaviour, but no, seems more common than ever there. Wherever you find it, it’s often infuriating. Where do people get off dictating how others should behave, putting restrictions on what they can say and do that they don’t adhere to themselves? It’s wrong and immoral, and shows that they can’t be trusted.

Or does it? In the scientific sense, hypocrisy is somewhat more complicated. It can manifest in several ways, and for several reasons, and often times the people guilty of it aren’t doing it purely to be self-serving.

Sometimes timing is the difference between being called a hypocrite or a saint. Photograph: Linda Nylind for the Guardian

The nature and timing of hypocrisy

A lot of things that are labelled hypocrisy may not actually be hypocritical, and a lot of the time, things that are hypocritical are given a pass because they are consistent with the observer’s worldview.

For example, someone who urges people to give money to charity but is then found out to give nothing themselves, they’d be considered a hypocrite. But if someone is known to be something of a skinflint then starts urging people to give to charity, they may still be considered a hypocrite, but it’s also possible they’ve just had a change of heart. Changing your mind or working for redemption are regularly considered good things. Bob Cratchit didn’t stop to accuse Scrooge of being a hypocrite.

Also, people tend to react more strongly to hypocrisy when it includes criticism or negative judgement. Someone boasts about being a live music supporter but is found to never go to gigs? Hypocritical, annoying, but not really worth getting angry about. But, a right-wing politician condemns homosexuality and attacks gay rights, but is then found to be engaging in homosexual activity themselves?Appalling. People react strongly to perceived injustice, so hypocrisy like this will get them very angry and demanding retribution.

Similarly, people are far quicker to notice and call out hypocrisy when it goes against their own beliefs. A politician you oppose promotes family values but is caught having an affair? Hypocrite! Drum them out of office! But if it’s a politician you support? Gutter journalism! So he’s not perfect, give him another chance! There are more important issues to worry about etc.

Basically, people aren’t 100% rational or consistent. Value judgements are typically subjective rather than objective, so the extent and seriousness of the hypocrisy is often in the eye of the beholder. This feeds into hypocrisy in other ways too.

We have a much higher opinion of ourselves than is usually warranted. Hopefully, other people will be willing to point this out. Photograph: PeopleImages.com/Getty Images

You think you’re better than others

Humans aren’t cold logical robots, and we typically have a higher opinion of ourselves than is warranted. Most humans have a self-serving bias, where we evaluate our own abilities and performance far more highly than is actually the case. People who achieve a certain level of intellectual achievement in certain contexts can reverse this, but we mostly think overly-well of ourselves.

It’s no surprise; the brain is riddled with cognitive and memory biases that are geared towards making us feel like we’re good and decent and capable, no matter what the reality. The problem is that our judgements of other people are far more “realistic”.

In some cases, this can lead to hypocrisy. A pilot would be well within her rights to stop an untrained person from assuming control of a plane, even though she does that all the time. This isn’t hypocrisy, this is simple acknowledgement of ability. Likewise, some people may tell others to do something and not do it themselves because they genuinely think they don’t need to do it, but the other inferior people need to be told. Not very nice, granted. May even not be a conscious decision. But it’s also not deliberate hypocrisy, if you look at it that way. Not that this makes any difference to the outcome, as far as most are concerned.

Thinking one thing and doing another can cause a lot of internal distress, and you just want it to go away. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Dissonance is disturbing

Those of you who are familiar with cognitive dissonance, the process whereby a mismatch between behaviour and attitudes/beliefs causes discomfort in the brain, may wonder why this doesn’t undermine hypocritical behaviour. Surely it would prevent people from doing things they openly condemn?

Again, it depends on the situation. Often, the “I’m better than other people so it’s OK” conclusion would be enough to reconcile it. But other times, it gets more serious. Take the earlier examples of anti-gay politicians found to be engaging in homosexual acts. This comes across as immensely hypocritical so they should be experiencing serious dissonance. But it could be argued that their actions are an attempt to resolve the dissonance. You’re raised in an environment that believes homosexuality is a sin, and you end up believing this completely. Why wouldn’t you? Then you hit adolescence and it turns out you are homosexual (it’s not a choice, after all). Now you’ve got serious dissonance; beliefs that insist homosexuality is wrong combined with physical attraction to the same sex.

One way to resolve this is to double down on the anti-gay behaviour. “I can’t be gay, look how much I hate them and work against them!” Now your beliefs and behaviour are more consistent, a sort of “fake it ‘til you make it” approach. But it’s difficult to maintain, as sex is a very powerful motivator, and people often aren’t strong enough to fight it. So you end up with strident anti-gay campaigners submitting to their desires. It’s not intentional hypocrisy in a sense, and it would be easy to only pity them for their struggles if they didn’t harm anyone else.

But they do. So it isn’t.

“I could work hard to be a good person, but... why bother?” Photograph: Blend Images/REX/Shutterstock

Hypocrisy is just easier

The problem with practising what you preach, or maintaining a high moral standard, is it’s work. You tell people to give money to charity or abstain from certain indulgences, this means you have to do these things too. But what if you just said you do these things, but didn’t? You get all the benefits of people thinking you’re a good and capable person, but you don’t have to practice any restraint. It’s win-win.

Humans are prone to the principal of least effort, often known as the “path of least resistance”, which means they’ll go for whatever option requires the least work. Hypocrisy allows you to appear principled without having to be so, which is much easier than adhering to strict principles. Modern politicians seem to have grasped this fact, making big speeches about all the great things they’ll do and then never doing any of them. Given how they seldom seem to suffer any consequences for their hypocrisy being revealed (i.e. any political event of 2016), why would they stop?

There are some positives though. Some studies show that, when called out on hypocrisy, people can end up more dedicated to the beliefs and practices they only claimed to adhere to previously. So don’t be afraid to point out hypocrisy when you see it, you might be doing some good overall.

And that includes hypocrisy about things you agree with, otherwise you’ll be… well, there’s a word for that.

Monday, 18 January 2016

Are modern cricketers more open to experimentation?

V Ramnarayan in Cricinfo

It was a cool December evening in the early 1980s. Flute maestro Hariprasad Chourasia was about to enter the iconic Kalakshetra auditorium in Chennai to perform in a concert when a young enthusiast asked him, "Will you please play the raga Hemant for me?" His reply was quick - and surprising, coming as it did from a leading classical musician of several years' standing. He said, "Sorry, I haven't learnt the raga yet." Some years later, I had a similar conversation with TV Vasan, a percussionist who played the mridangam, a south Indian drum. He spoke about a conversation he once had with the doyen of Carnatic music, Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar. Vasan, who had watched Iyengar practise a particular song some 500 times during the month, was eager to hear it in concert on the morrow. That was not to be. "I haven't mastered it," said the singer.

More recently I read about another old master's advice to young musicians. Semmangudi Srinivasier, grand old patriarch of Carnatic music, said to his disciples: "Practise every song at least a thousand times before you take it to the concert platform." MS Subbulakshmi, perhaps the best known south Indian voice, was famous for doing just that. She knew every lyric of every song backwards, regardless of language or complexity, and still had butterflies in her stomach before every concert. The rigour extended even to studio recordings, where she could well have resorted to external aids with nobody the wiser for it.

The situation is different today. Without criticising or condemning modern musicians, it can be said truthfully of most that they do not match the older generation in their preparation for performances. Many look into their iPads or cell phones while performing on stage, possibly because their song repertoires are far larger than those of their gurus were. It is not unusual for a song learnt in the morning to debut in the evening.

What has all this to do with cricket? It is that I find some parallels between the two. For instance, I remember watching Erapalli Prasanna, during his last Ranji Trophy match, I think, bowl in the nets a delivery that looked similar to the doosra of a later era. Bowling in an adjacent net, and fascinated by the new variation, I asked him how come I never saw the delivery in a match. "Haven't mastered it," was his reply.

In my experience, experiments were frowned upon in matches. You were sure to get a tongue-lashing from your seniors if you tried something novel in a game. Mumtaz Hussain, a successful left-arm spinner in first-class cricket, might have been even more successful if he had continued to bowl the chinaman and the googly as he had done in his university days, instead of turning into an orthodox spinner and serving his side in a risk-free manner. Though Bhagwath Chandrasekhar and Anil Kumble were unorthodox wrist spinners, much quicker than the norm, neither added variations - like a slower ball - to his armoury before he was well into his career. Similarly, most international bowlers were reluctant to try reverse swing until long after the Pakistanis unfurled it.

The second decade of this century has been a watershed in this regard, with both bowlers and batsmen increasingly ready to take risks. To the reverse sweep has been added the switch hit, and the likes of offspinner R Ashwin (among those whose actions have not been questioned) have been attempting numerous variations, including the legbreak, whose destructive potential is as yet unknown.

I shudder to think what choice French my captain might have resorted to had I resorted to such experimentation in my day. As a result of such a mindset - which most of my contemporaries shared - I was so cautious that once, after hitting Tamil Nadu batsman P Mukund's off stump in a Ranji Trophy match (by sheer fluke) with a delivery I bowled from round the wicket, gripping the ball with my palm, I never tried the variation in all 15 years of cricket that followed. However, lest I be misunderstood to be an advocate of the current trend of launching untested or insufficiently tested products, let me stress that I am indeed an admirer of the perfectionism of the old guard.

It was a cool December evening in the early 1980s. Flute maestro Hariprasad Chourasia was about to enter the iconic Kalakshetra auditorium in Chennai to perform in a concert when a young enthusiast asked him, "Will you please play the raga Hemant for me?" His reply was quick - and surprising, coming as it did from a leading classical musician of several years' standing. He said, "Sorry, I haven't learnt the raga yet." Some years later, I had a similar conversation with TV Vasan, a percussionist who played the mridangam, a south Indian drum. He spoke about a conversation he once had with the doyen of Carnatic music, Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar. Vasan, who had watched Iyengar practise a particular song some 500 times during the month, was eager to hear it in concert on the morrow. That was not to be. "I haven't mastered it," said the singer.

More recently I read about another old master's advice to young musicians. Semmangudi Srinivasier, grand old patriarch of Carnatic music, said to his disciples: "Practise every song at least a thousand times before you take it to the concert platform." MS Subbulakshmi, perhaps the best known south Indian voice, was famous for doing just that. She knew every lyric of every song backwards, regardless of language or complexity, and still had butterflies in her stomach before every concert. The rigour extended even to studio recordings, where she could well have resorted to external aids with nobody the wiser for it.

The situation is different today. Without criticising or condemning modern musicians, it can be said truthfully of most that they do not match the older generation in their preparation for performances. Many look into their iPads or cell phones while performing on stage, possibly because their song repertoires are far larger than those of their gurus were. It is not unusual for a song learnt in the morning to debut in the evening.

What has all this to do with cricket? It is that I find some parallels between the two. For instance, I remember watching Erapalli Prasanna, during his last Ranji Trophy match, I think, bowl in the nets a delivery that looked similar to the doosra of a later era. Bowling in an adjacent net, and fascinated by the new variation, I asked him how come I never saw the delivery in a match. "Haven't mastered it," was his reply.

In my experience, experiments were frowned upon in matches. You were sure to get a tongue-lashing from your seniors if you tried something novel in a game. Mumtaz Hussain, a successful left-arm spinner in first-class cricket, might have been even more successful if he had continued to bowl the chinaman and the googly as he had done in his university days, instead of turning into an orthodox spinner and serving his side in a risk-free manner. Though Bhagwath Chandrasekhar and Anil Kumble were unorthodox wrist spinners, much quicker than the norm, neither added variations - like a slower ball - to his armoury before he was well into his career. Similarly, most international bowlers were reluctant to try reverse swing until long after the Pakistanis unfurled it.

The second decade of this century has been a watershed in this regard, with both bowlers and batsmen increasingly ready to take risks. To the reverse sweep has been added the switch hit, and the likes of offspinner R Ashwin (among those whose actions have not been questioned) have been attempting numerous variations, including the legbreak, whose destructive potential is as yet unknown.

I shudder to think what choice French my captain might have resorted to had I resorted to such experimentation in my day. As a result of such a mindset - which most of my contemporaries shared - I was so cautious that once, after hitting Tamil Nadu batsman P Mukund's off stump in a Ranji Trophy match (by sheer fluke) with a delivery I bowled from round the wicket, gripping the ball with my palm, I never tried the variation in all 15 years of cricket that followed. However, lest I be misunderstood to be an advocate of the current trend of launching untested or insufficiently tested products, let me stress that I am indeed an admirer of the perfectionism of the old guard.

Monday, 20 April 2015

Cricket Coaching: Follow in the bare footsteps of the Kalenjin

Ed Smith in Cricinfo

What can the story of running shoes among Kenyan athletes teach us about cricket? More than I thought possible.

Nearly all top marathon runners are Kenyan. In fact, they are drawn from a particular Kenyan tribe, the Kalenjin, an ethnic group of around 5 million people living mostly at altitude in the Rift Valley.

Here is the really interesting thing. The majority of top marathon runners grow up running without shoes. The debate about whether other athletes should try to mimic barefoot-running technique remains contested and unresolved. However, it is overwhelmingly likely that the unshod childhoods of the Kalenjin does contribute to their pre-eminence as distance runners.*

And yet it is also true that as soon as Kalenjin athletes can afford running shoes, they do buy them. They know that the protection offered by modern shoes helps them to rack up the epic number of hours of training required to become a serious distance runner.

So there is a paradox about long-term potential and running shoes. If an athlete wears shoes too often and too early, when his natural technique and running style are still evolving, he significantly reduces his chances of becoming a champion distance runner. But if he doesn't wear them at all in the later stages of his athletic education he jeopardises his ability to train and perform optimally when it matters.

Put simply, the advantages of modernity and technology need to be first withheld and then embraced. Most Kenyan runners begin wearing trainers in their mid-teens. Some sports scientists argue that if they could hold off for another two or three years, they'd be even better as adult athletes. But no one knows for sure exactly when is the "right" time to start running in shoes. We glimpse the ideal athletic childhood, but its contours remain extremely hazy.