'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label intuition. Show all posts

Showing posts with label intuition. Show all posts

Monday, 22 January 2024

Sunday, 1 October 2023

Should you trust your sixth sense?

Hannah Ewens in The Guardian

To escape an unresolved work challenge, Archimedes went to the local baths. As he got into the water and noticed the liquid spilling over the edge, it happened. The mathematician jumped up and ran home naked, crying “Eureka! I’ve found it!” Over two millennia later, in 2010, it is Gwyneth Paltrow’s 38th birthday weekend in Italy. Her eureka moment is involuntary, like “the ring of a bell that has sounded and cannot be undone”. She knew her marriage was over. Soon after I read about this incident in her infamous conscious uncoupling essay, I saw a name on an email and knew I’d date that person, without knowing who they were or what they looked like. Whether it’s the Archimedes principle or a divorce from Chris Martin or love-at-first-email, intuition is a funny, evasive thing with human consequences.

Following these sudden realisations or hits of intuition used to be the way I lived: a bell would ring out and I’d run fully clothed but without fear from one opportunity to the next. It’s hard to quantify a “just knowing” in the body. If forced to, I’d say my intuition would be instant, inexplicable and irrational. Like if you told the nearest person what you’d just learned, they’d rigidly smile, get up and change seats. For example, I’ve known I’d work at a specific company after hearing it mentioned in a classroom; as with Archimedes, the idea for my first book dropped into my head fully formed; and like Paltrow, I’ve known jarringly, in an otherwise content moment, that a relationship was absolutely over. I’d get it with small, seemingly unimportant things, too. I’d think of a loved one I hadn’t spoken to in months and a minute later they’d call needing my help. This could sound like magical thinking or a collection of unremarkable coincidences. I sincerely don’t know how damning this phenomenon is to write about because, until recently, I hadn’t spoken in depth to anyone about it. But I do suspect that for many of us, intuition is not a completely foreign experience.

About 10 months ago, my internal workings changed. A year prior, I’d followed these moments of intuition into a dream job, new neighbourhood, new friends and a relationship with the person I thought was the love of my life. I was blissfully happy. My world felt so big, as though if I kept using this medium, anything was possible. But almost immediately, it all disappeared in an abrupt and undignified manner. This lightning bolt of change seemed to bring with it the loss of my intuition.

I have the uncanny feeling of existing outside the flow of life. It’s different to being depressed, it’s more energetic and esoteric: an awareness that everything is growing, flourishing and dying, connections and signs are being traded, and you’ve slipped out of nature’s systemisation. I’m watching the sky for a signal and nothingness stares back at me. I’m not without purpose, but I feel stagnant, disoriented. It seems impossible to make future plans without the inner guidance I once trusted.

Then I realised that if intuition is real, I can study it and try to bring it back.

Despite intuition being one of the most significant concepts in western philosophy, central to the ancient Greeks (Plato and Aristotle), through to thinkers of the early modern period (Descartes) and romanticism (Kant), ideas about it differ. Science and psychology don’t conclusively know what it is either, with research typically building on the work of Nobel prize-winning psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman, who proposed that we have two different thought systems: one is fast and intuitive, the other is slower and analytical. These various disciplines do, however, acknowledge that it’s important and they do believe it’s real.

Joel Pearson, a psychologist, neuroscientist and author of the forthcoming book The Intuition Toolkit, has given the subject a working definition in order to study it: the learned use of conscious information to improve decisions or actions. “Most people think of it as the gut response,” he tells me. “You feel it in the body and you don’t know where it comes from. It’s knowing what without knowing why.”

Through his research, Pearson has learned that intuition is incredibly useful in a number of situations – and potentially disastrous in others. He uses the acronym Smile. S is for self-awareness: if you’re feeling emotional, don’t trust your intuition. M is for mastery: you need to actually know about the area in which you’re being intuitive. Don’t take a lucky gamble on the stock market based on gut feeling when you know nothing about finance. I is for impulses: you’re not feeling an intuitive draw towards food, drugs, social media… those are cravings. L is for low probability: don’t use intuition for probabilistic judgments. “Anything with numbers or probabilities: whatever you feel is probably wrong,” Pearson says. And the last is E for environment: only trust your intuition in familiar – therefore fairly predictable – environments.

To escape an unresolved work challenge, Archimedes went to the local baths. As he got into the water and noticed the liquid spilling over the edge, it happened. The mathematician jumped up and ran home naked, crying “Eureka! I’ve found it!” Over two millennia later, in 2010, it is Gwyneth Paltrow’s 38th birthday weekend in Italy. Her eureka moment is involuntary, like “the ring of a bell that has sounded and cannot be undone”. She knew her marriage was over. Soon after I read about this incident in her infamous conscious uncoupling essay, I saw a name on an email and knew I’d date that person, without knowing who they were or what they looked like. Whether it’s the Archimedes principle or a divorce from Chris Martin or love-at-first-email, intuition is a funny, evasive thing with human consequences.

Following these sudden realisations or hits of intuition used to be the way I lived: a bell would ring out and I’d run fully clothed but without fear from one opportunity to the next. It’s hard to quantify a “just knowing” in the body. If forced to, I’d say my intuition would be instant, inexplicable and irrational. Like if you told the nearest person what you’d just learned, they’d rigidly smile, get up and change seats. For example, I’ve known I’d work at a specific company after hearing it mentioned in a classroom; as with Archimedes, the idea for my first book dropped into my head fully formed; and like Paltrow, I’ve known jarringly, in an otherwise content moment, that a relationship was absolutely over. I’d get it with small, seemingly unimportant things, too. I’d think of a loved one I hadn’t spoken to in months and a minute later they’d call needing my help. This could sound like magical thinking or a collection of unremarkable coincidences. I sincerely don’t know how damning this phenomenon is to write about because, until recently, I hadn’t spoken in depth to anyone about it. But I do suspect that for many of us, intuition is not a completely foreign experience.

About 10 months ago, my internal workings changed. A year prior, I’d followed these moments of intuition into a dream job, new neighbourhood, new friends and a relationship with the person I thought was the love of my life. I was blissfully happy. My world felt so big, as though if I kept using this medium, anything was possible. But almost immediately, it all disappeared in an abrupt and undignified manner. This lightning bolt of change seemed to bring with it the loss of my intuition.

I have the uncanny feeling of existing outside the flow of life. It’s different to being depressed, it’s more energetic and esoteric: an awareness that everything is growing, flourishing and dying, connections and signs are being traded, and you’ve slipped out of nature’s systemisation. I’m watching the sky for a signal and nothingness stares back at me. I’m not without purpose, but I feel stagnant, disoriented. It seems impossible to make future plans without the inner guidance I once trusted.

Then I realised that if intuition is real, I can study it and try to bring it back.

Despite intuition being one of the most significant concepts in western philosophy, central to the ancient Greeks (Plato and Aristotle), through to thinkers of the early modern period (Descartes) and romanticism (Kant), ideas about it differ. Science and psychology don’t conclusively know what it is either, with research typically building on the work of Nobel prize-winning psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman, who proposed that we have two different thought systems: one is fast and intuitive, the other is slower and analytical. These various disciplines do, however, acknowledge that it’s important and they do believe it’s real.

Joel Pearson, a psychologist, neuroscientist and author of the forthcoming book The Intuition Toolkit, has given the subject a working definition in order to study it: the learned use of conscious information to improve decisions or actions. “Most people think of it as the gut response,” he tells me. “You feel it in the body and you don’t know where it comes from. It’s knowing what without knowing why.”

Through his research, Pearson has learned that intuition is incredibly useful in a number of situations – and potentially disastrous in others. He uses the acronym Smile. S is for self-awareness: if you’re feeling emotional, don’t trust your intuition. M is for mastery: you need to actually know about the area in which you’re being intuitive. Don’t take a lucky gamble on the stock market based on gut feeling when you know nothing about finance. I is for impulses: you’re not feeling an intuitive draw towards food, drugs, social media… those are cravings. L is for low probability: don’t use intuition for probabilistic judgments. “Anything with numbers or probabilities: whatever you feel is probably wrong,” Pearson says. And the last is E for environment: only trust your intuition in familiar – therefore fairly predictable – environments.

Gut instinct: it can be tremendously effective, but can you trust it? Illustration: Ana Yael

While Pearson insists there is nothing otherworldly about intuition, other branches of knowledge romanticise it in this way. Philosophers Henri Bergson and Carl Jung are famous for infusing something more into its origins. In multiple religious traditions, intuition is associated with a path to the divine. “There’s always been this mystical spiritual overlay, even in the very oldest senses of the term,” says Lisa Osbeck, professor of psychology at the University of West Georgia and co-editor ofthe philosophical book Rational Intuition.

Osbeck has noticed, as I have, that intuition is the latest popular wellness expression. Online courses, coaches and lifestyle influencers encourage followers to heed their intuition, “intuit” the information around them, and live an intuitive life. Together we hypothesise about why this is happening now: a lack of trust in the media, an abundance of information hitting us in our lives and on our screens – everyone telling us what to do to do life right – and a decline of organised religion leaving a spiritual hunger to be sated. “There’s a special appeal to just trusting this bedrock within us,” she says. If the messaging from outside us is stressful and contradictory, then at least there is this sanctified ideal of a trusted inner compass.

In my most discreet asking-for-a-friend voice, I question why people might typically say that they’ve lost their intuition. “They’ve lost confidence in their own judgment,” Osbeck answers. “It’s less threatening to attach it to some special ability that you can gain or lose, like ‘the muse’. It takes the responsibility away from the person.”

I take this eviscerating read of the situation on the chin, but part of me resists. Only I am responsible for acting blindly on intuition and I know that. I now needed to speak to someone who combines all the disciplines: philosophical, psychological and the spiritual. Someone like Fleur Leussink, who trained in neuroscience, became a spiritual adviser to the stars, and now works as an intuition teacher. When she mentioned on the phone she was doing an intuition retreat soon, the first intuitive hit in months arrived: I knew I had to be there.

To use intuition, you must go from the overthinking of the mind into the body and as such, Leussink’s week-long intuition retreats focus on nervous system regulation. This happens with relative ease when you’re deep enough in the Italian countryside with non-committal signal and no internet, the workshop room has the ambience of a church and you’re hugged by woodland from every direction. Days were bookended with various different breathing practices, meditations and somatic movements that forced our bodies to feeling more grounded. This, Leussink advised, “makes space for intuition to rise” up in us.

To benefit from a retreat, you have to see it as a container without the scaffolding of social mores and your own governing rules of embarrassment. Mealtimes were a chance to learn why other people were there. It was mostly women, of all ages, from Europe, the US and Canada. Some had been through paradigm-shattering losses that made mine look petty and provincial. I quickly gravitated towards one woman in her mid-20s, whose intuition had pushed her into a break-up and to consider changing her PhD entirely; she wanted to learn how to harness whatever that mystery force was. Everyone had the same barrier to action, they were seeking reassurance: this intuition thing is real, right?

In classes about the psychology and practice of intuition, we got closer to an answer. Leussink’s take on intuition felt true to my experience: “Energetic information translated by the body into conscious thought about you, for you.” The emotion-releasing meditations and movements we were doing made sense as the week progressed – the different feelings located in a body included echoes of trauma, spikes of anxiety, empathy for the moods of the people around us, all distinct from intuition. When you have all that going on, Leussink said, how can you possibly recognise the more subtle prompts?

In one session, she asked us to remember the times we experienced intuition in our lives. I listed them in my notebook. You may believe intuition accidentally happened to you, she explained, but you were in the space for it to happen: calm, most likely in theta brainwave (the brainwave found when meditating or doing something repetitive), crucially not thinking about the pressing questions you are now mulling over (see Archimedes’s moment of truth).

It doesn’t mean you have to take its guidance, it is just another perspective, she said. It’s then that I understood what my question had been all along: what was my intuition for? It led me through chaotic and extreme places and left me at square one emotionally and practically. When I asked, Leussink explained that it was a philosophical question that we had to answer for ourselves. “For me, intuition is for living your most expansive life,” adding that crucially, “that’s not necessarily the easiest road, but it can be the most transformative.” This is the moment everything slides into 20/20 clarity. Above anything else, intuition has led me to evolution and something like self-awareness.

A dozen times over the week, I let myself think about the real reason I was there: through my intuition I had found a charged and true relationship, inside of which, suddenly, nothing was what it seemed. I remembered the moment I felt someone walking up behind me and knew they would change my life forever. Imagining that outdoor seating area, I could smell the cheap coffee in front of me, feel the warmth of Los Angeles in its coldest months, remember that knowledge landing in my body, then the heavy movement of his jacket as he strode around and sat down in front of me. I wanted to compel the past: don’t have that knowing, please don’t or do. I’m not sure. You don’t know what I know now.

One night while lying in my bed, I listened to a message my friend had sent me. She’d just finished an intense whirlwind romance, having missed what we now love to culturally diagnose as red flags. “At least you learned something valuable,” I stoically wrote back, after a long day of observing autumn leaves fall and anthropomorphising my own slow but inevitable ability to heal on to trees. She replied: “Fuck lessons, man.” It was fair enough.

On the last day, Leussink gave us an exercise with a pendulum to access our beliefs around intuition. Given why I’m here, I assumed my subconscious belief was that I don’t believe it’s safe to trust it – that would be keeping my intuition away. But it wasn’t.

Do I believe it is safe for me to follow my intuition? My subconscious mind gave a quiet but unwavering yes – following my intuition is safe for me. My conscious mind said no. Of course, deep down I believe my intuition is supportive of me in some way, because that’s been my default setting. It’s my conscious mind that is struggling with the lack of safety. I understand why that is, because I don’t want more change, I don’t want more pain. What Osbeck suggested, Leussink confirmed: the problem wasn’t with intuition, it was with me. There is no over-intellectualising something as straightforward and primeval as intuition. Imbue it with spiritual intention or don’t. It will run across the state lines of your body like a train in the night, and then it’s gone.

While Pearson insists there is nothing otherworldly about intuition, other branches of knowledge romanticise it in this way. Philosophers Henri Bergson and Carl Jung are famous for infusing something more into its origins. In multiple religious traditions, intuition is associated with a path to the divine. “There’s always been this mystical spiritual overlay, even in the very oldest senses of the term,” says Lisa Osbeck, professor of psychology at the University of West Georgia and co-editor ofthe philosophical book Rational Intuition.

Osbeck has noticed, as I have, that intuition is the latest popular wellness expression. Online courses, coaches and lifestyle influencers encourage followers to heed their intuition, “intuit” the information around them, and live an intuitive life. Together we hypothesise about why this is happening now: a lack of trust in the media, an abundance of information hitting us in our lives and on our screens – everyone telling us what to do to do life right – and a decline of organised religion leaving a spiritual hunger to be sated. “There’s a special appeal to just trusting this bedrock within us,” she says. If the messaging from outside us is stressful and contradictory, then at least there is this sanctified ideal of a trusted inner compass.

In my most discreet asking-for-a-friend voice, I question why people might typically say that they’ve lost their intuition. “They’ve lost confidence in their own judgment,” Osbeck answers. “It’s less threatening to attach it to some special ability that you can gain or lose, like ‘the muse’. It takes the responsibility away from the person.”

I take this eviscerating read of the situation on the chin, but part of me resists. Only I am responsible for acting blindly on intuition and I know that. I now needed to speak to someone who combines all the disciplines: philosophical, psychological and the spiritual. Someone like Fleur Leussink, who trained in neuroscience, became a spiritual adviser to the stars, and now works as an intuition teacher. When she mentioned on the phone she was doing an intuition retreat soon, the first intuitive hit in months arrived: I knew I had to be there.

To use intuition, you must go from the overthinking of the mind into the body and as such, Leussink’s week-long intuition retreats focus on nervous system regulation. This happens with relative ease when you’re deep enough in the Italian countryside with non-committal signal and no internet, the workshop room has the ambience of a church and you’re hugged by woodland from every direction. Days were bookended with various different breathing practices, meditations and somatic movements that forced our bodies to feeling more grounded. This, Leussink advised, “makes space for intuition to rise” up in us.

To benefit from a retreat, you have to see it as a container without the scaffolding of social mores and your own governing rules of embarrassment. Mealtimes were a chance to learn why other people were there. It was mostly women, of all ages, from Europe, the US and Canada. Some had been through paradigm-shattering losses that made mine look petty and provincial. I quickly gravitated towards one woman in her mid-20s, whose intuition had pushed her into a break-up and to consider changing her PhD entirely; she wanted to learn how to harness whatever that mystery force was. Everyone had the same barrier to action, they were seeking reassurance: this intuition thing is real, right?

In classes about the psychology and practice of intuition, we got closer to an answer. Leussink’s take on intuition felt true to my experience: “Energetic information translated by the body into conscious thought about you, for you.” The emotion-releasing meditations and movements we were doing made sense as the week progressed – the different feelings located in a body included echoes of trauma, spikes of anxiety, empathy for the moods of the people around us, all distinct from intuition. When you have all that going on, Leussink said, how can you possibly recognise the more subtle prompts?

In one session, she asked us to remember the times we experienced intuition in our lives. I listed them in my notebook. You may believe intuition accidentally happened to you, she explained, but you were in the space for it to happen: calm, most likely in theta brainwave (the brainwave found when meditating or doing something repetitive), crucially not thinking about the pressing questions you are now mulling over (see Archimedes’s moment of truth).

It doesn’t mean you have to take its guidance, it is just another perspective, she said. It’s then that I understood what my question had been all along: what was my intuition for? It led me through chaotic and extreme places and left me at square one emotionally and practically. When I asked, Leussink explained that it was a philosophical question that we had to answer for ourselves. “For me, intuition is for living your most expansive life,” adding that crucially, “that’s not necessarily the easiest road, but it can be the most transformative.” This is the moment everything slides into 20/20 clarity. Above anything else, intuition has led me to evolution and something like self-awareness.

A dozen times over the week, I let myself think about the real reason I was there: through my intuition I had found a charged and true relationship, inside of which, suddenly, nothing was what it seemed. I remembered the moment I felt someone walking up behind me and knew they would change my life forever. Imagining that outdoor seating area, I could smell the cheap coffee in front of me, feel the warmth of Los Angeles in its coldest months, remember that knowledge landing in my body, then the heavy movement of his jacket as he strode around and sat down in front of me. I wanted to compel the past: don’t have that knowing, please don’t or do. I’m not sure. You don’t know what I know now.

One night while lying in my bed, I listened to a message my friend had sent me. She’d just finished an intense whirlwind romance, having missed what we now love to culturally diagnose as red flags. “At least you learned something valuable,” I stoically wrote back, after a long day of observing autumn leaves fall and anthropomorphising my own slow but inevitable ability to heal on to trees. She replied: “Fuck lessons, man.” It was fair enough.

On the last day, Leussink gave us an exercise with a pendulum to access our beliefs around intuition. Given why I’m here, I assumed my subconscious belief was that I don’t believe it’s safe to trust it – that would be keeping my intuition away. But it wasn’t.

Do I believe it is safe for me to follow my intuition? My subconscious mind gave a quiet but unwavering yes – following my intuition is safe for me. My conscious mind said no. Of course, deep down I believe my intuition is supportive of me in some way, because that’s been my default setting. It’s my conscious mind that is struggling with the lack of safety. I understand why that is, because I don’t want more change, I don’t want more pain. What Osbeck suggested, Leussink confirmed: the problem wasn’t with intuition, it was with me. There is no over-intellectualising something as straightforward and primeval as intuition. Imbue it with spiritual intention or don’t. It will run across the state lines of your body like a train in the night, and then it’s gone.

Thursday, 16 June 2022

‘If you work hard and succeed, you’re a loser’: can you really wing it to the top?

Forget the spreadsheets and make it up as you go along – that’s the message of leaders from Elon Musk to Boris Johnson. But is acting on instinct really a good idea? Emma Beddington in The Guardian

There are, it seems, two types of “winging it” stories. First, there are the triumphant ones – the victories pulled, cheekily, improbably, from the jaws of defeat. Like the time a historian (who prefers to remain nameless) turned up to give a talk on one subject, only to discover her hosts were expecting, and had advertised, another. “I wrote the full thing – an hour-long show – in 10 panicked minutes,” she says. “At the end, a lady came up to congratulate me on how spontaneous my delivery was.”

Then there is the other kind of winging it story – the kind that ends in ignominy. Remember the safeguarding minister, Rachel Maclean, tying herself in factually inaccurate knots when asked about stop-and-search powers? The Australian journalist Matt Doran, who interviewed Adele without listening to her album? Or the culture secretary, Nadine Dorries, claiming Channel 4 was publicly funded, then that Channel 5 had been privatised?

There are even worse examples. As a young journalist, Sarah Dempster was unwell when she was supposed to review a Meat Loaf concert, so she wrote the piece without attending. “An hour after publication, the paper called to inform me that the gig had, in fact, been cancelled. I was sacked,” she tweeted. “The Sun wrote a piece about it. The headline: ‘MEAT OAF’.”

Why does anyone wing it, and how do they dare? As a lifelong dreary prepper, I have been wondering this since reading a profile in the New York Times of winger extraordinaire Elon Musk. “To a degree unseen in any other mogul, the entrepreneur acts on whim, fancy and the certainty that he is 100% right,” it related, detailing how Musk wings even the biggest decisions, operating on gut feeling and without a business plan, rejecting expert advice.

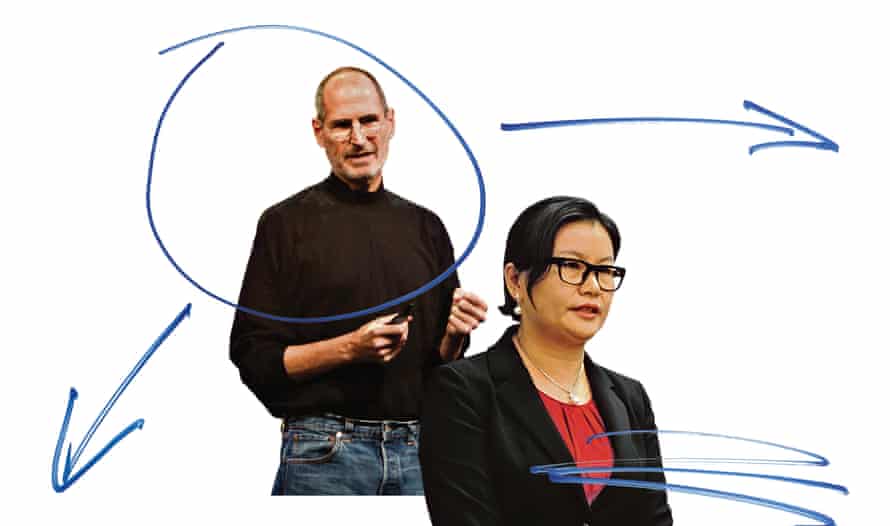

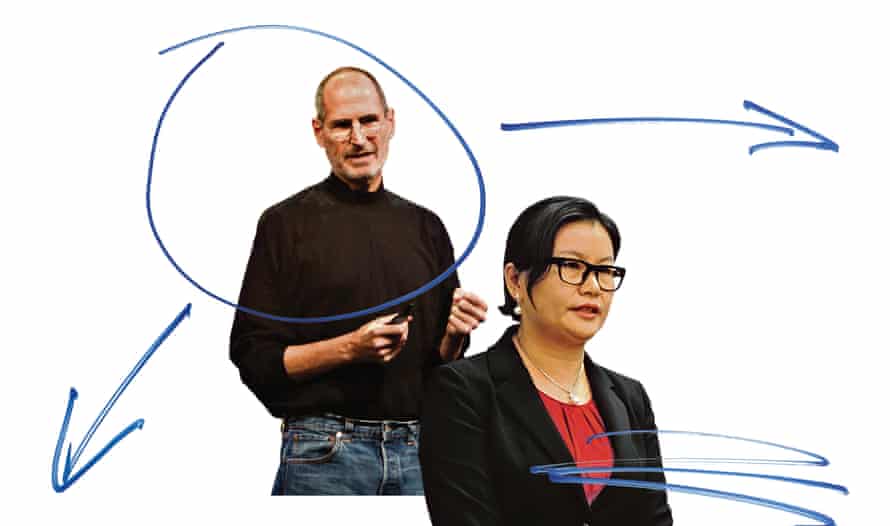

Genius or graft? Apple founder Steve Jobs and Zhou Qunfei, China’s richest woman. Composite: Getty/Shutterstock/Guardian Design

Genius or graft? Apple founder Steve Jobs and Zhou Qunfei, China’s richest woman. Composite: Getty/Shutterstock/Guardian Design

What, I wonder, is the appeal of this strategy? And is it a legitimate – indeed, more successful – way of doing business? Can Musk, the CEO of Tesla (a company with a market capitalisation of £570bn) and the founder of SpaceX (the first private company to send humans into space) really be winging it?

Some are sceptical. “Is this self-presentation or an accurate statement?” asks Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, an organisational psychologist and the author of Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? “Musk is probably way too smart to actually operate under that principle; he uses this arrogant self-presentation to his advantage. Brand Musk accounts for a big chunk of his success.” In contrast, he says, the recent Netflix SpaceX documentary shows Musk as “quite self-critical, quite humble”.

It is an idea echoed by Stefan Stern, a visiting professor at the Bayes Business School at City, University of London and the author of Myths of Management. “I can’t believe that he doesn’t draw on data; it’s a leading-edge thing he’s engaged in. When you promote yourself as a sort of visionary or hero, you absolutely want to try to claim that there’s something special about your insights – they’re not a petty, banal matter of data.”

The implication is that Musk is like those schoolkids who claim not to have done a minute’s revision, then ace the exam. There is, the argument goes, something innately appealing about someone operating effortlessly on flair, instinct and inspiration: a Steve Jobs, not a Zhou Qunfei – the discreet founder of Lens Technology and the richest woman in China, who, Chamorro-Premuzic says, credits her success to “hard work and a relentless desire to learn”.

“There’s something romantic to the idea that there are mavericks who don’t need to work very hard,” adds Chamorro-Premuzic. “We say we value hard work and dedication, but, by definition, talent is more of an extraordinary gift and we celebrate that more.”

The leadership expert Eve Poole agrees. “No one wants to make it feel like hard work,” she says. “No one wants to say: ‘I slaved in front of a spreadsheet for 20 hours before I made that decision.’”

For Stern, Boris Johnson’s apparent penchant for winging it carries a similar message. “When he says: ‘We got the big calls right,’ he’s saying: ‘These small-minded people obsess about data and numbers and statistics, but with my instinct, my judgment, I – the uniquely gifted, insightful leader – got the big calls right.’ It’s not even true!”

His self-presentation as “a charismatic figure with panache who is apparently spontaneous” is particularly interesting, Stern says, given that “the other thing we know about Johnson is he’s not spontaneous, he doesn’t have good lines off the cuff”. (See that disastrous CBI Peppa Pig speech in November, recent prime minister’s questions performances or his testy, defensive responses in more probing interviews.)

Is there any foundation for the notion that gut feeling is superior to pedestrian, data-driven decision-making? The cognitive psychologist Gary Klein has spent his career researching intuition in decision-making; 35 years on, his research on how firefighters act swiftly under pressure in tough situations is still cited. “We weren’t looking for intuition,” he says. Rather, his team’s original theory was that firefighters might be rapidly evaluating two options when they decided how to tackle a fire. “They told us: ‘We don’t compare any options.’ More than that, they said: ‘We never make any decisions.’” Klein didn’t understand how firefighters could believe only one course of action was possible and land on it without making comparisons.

Further digging revealed a different picture. With 15 to 20 years of experience, Klein explains, the firefighters were classifying the situation based on fires they had seen – a process known as “pattern matching”. The second step Klein called “mental simulation”: the firefighters would visualise how a course of action would run and adjust their model accordingly. “It’s a blend of intuition and analysis,” says Klein. The process was near-instantaneous. “Most decisions were made in less than a minute.”

So, what looks like winging it can, in fact, be instinctive decision-making backed up by experience – what Poole calls “really quick heuristics in your brain … synaptic connections established through years of conditioning”. Leaders who trust that, she says, “are just fucking excellent”.

This decision-making model is common in one of the areas where people are least comfortable with the idea of winging it: healthcare. No one wants to end up in the hands of a seat-of-the-pants neurosurgeon, but Klein’s research suggests medical professionals use intuitive decision-making and gut feeling as a matter of course.

His book The Power of Intuition tells the story of an experienced neonatal intensive care unit nurse accurately diagnosing a baby with sepsis just by walking past the incubator and getting a gut feeling, when a less experienced nurse who had been conscientiously tracking all the infant’s vitals had failed to spot it. “An experienced physician sees a cluster of cues and says sepsis. We’ve heard stories of someone who was just a resident; there was a tough case and they called the attending physician. The attending physician does not even enter the room and from the door just looks at the patient and sees there’s an issue and says: ‘Ah, congestive heart failure.’”

Firefighters in New York. Gary Klein’s research suggests they use ‘a blend of intuition and analysis’ to make quick decisions. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Firefighters in New York. Gary Klein’s research suggests they use ‘a blend of intuition and analysis’ to make quick decisions. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The experiences that feed intuition can be less concrete. Poole has been researching what humans still have to offer in a world in which AI is ever-more powerful, such as what she calls “witch-style intuition” – that sense of foreboding when you enter a room or meet someone. “We all know we have had those feelings and we tend to discount them and think they’re a bit silly and weird,” she says. “But I think it’s probably coming from the collective historical unconscious, trying to keep us safe as a species.” There are, she says, two strands: “your own, desperately hard-earned gut feeling, laid down in templates of data and knowledge, then the spooky ephemera that you can pick up through ‘spidey sense’, which I think can still be really reliable.”

It can, but it isn’t always. Intuition of any kind is not infallible. Klein describes it as a “data point”: something to take into consideration, not to accept uncritically. One area in which intuition gives demonstrably poor outcomes is recruitment. As Chamorro-Premuzic explains, unstructured interview processes increase and reinforce conscious and unconscious biases about candidates. We all believe our own intuition to be superior, he says: “In an interview situation, this is a big problem, because hiring managers think they have an ability to see through candidates and to understand whether they are competent.” Companies will spend large budgets on diversity and inclusion, “then tell you they hire for ‘culture fit’ – and the main way to evaluate culture fit is whether somebody ‘feels right’ in a job interview. Even if managers are well-meaning and open-minded, they will gravitate towards candidates who are like them and they are comfortable with.”

Moreover, studies show that people tend to make up their mind in the first 60 or 90 seconds, he says. This is pattern recognition gone wrong, according to Stern. When decision-makers see someone who reminds them of themselves, they think: “Oh yeah, he’s got the right stuff. I used to be like him.”

Donald Trump springs to mind here. I read Klein a typical Trump pronouncement: “I have a gut and my gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me.” It reminds Klein of two dangerous fallacies about intuition: “One, some people think intuition is innate ability, which I don’t think it is; it’s based on experience. Two, intuition is a general skill and will apply in lots of different situations. I don’t think that’s true.” Having decent intuition in an area where you have professional experience – “like real estate”, he says, pointedly – does not mean you have a transferable skill.

Talking to people who admit to winging it reveals that, mainly, they mean the “good” kind of intuition: calling on a wealth of relevant experience and deploying it in defined circumstances. That often involves an element of performance, where spontaneity can be the secret ingredient.

Susannah, who works in publishing, says: “I love to wing it in sales presentations. When I wing it, I suddenly find a new angle; it works every time. But only, I think, because I’m winging stuff I already know deeply.” Kathy, a senior financial services strategist, says: “If it’s something I don’t know at all, I won’t wing it, but in my area of expertise I’m the queen of prep five minutes before the meeting.”

These are the good wingers, but of course the bad ones are out there – the lazy, the grandiose blaggers and the bullshitters, too often in positions of power. “There are a lot of men, particularly, who do that,” says Poole. “I think it does appeal to people who don’t feel anything any more – it’s all so boring and that’s the way they get some feelings. It gives them a massive adrenaline rush; it makes them feel very powerful and victorious.” It is not usually a successful long-term strategy, she adds, comfortingly; what Chamorro-Premuzic calls “the sense of Teflon-style immunity” betrays them eventually. “I just think you get caught out. It’s the spin of the wheel and that’s why I hate it: it’s so risky for your organisation.”

But we still admire them, buy their products, even vote for them. Why do we fall for it? It is a lack of “followership maturity”, according to Chamorro-Premuzic, and varies from culture to culture. “I grew up in South America, where if you work hard and you succeed you’re automatically a loser,” he says. “Whereas if you bullshit and deceive people, we should worship you. There are cultures that truly value self-improvement, hard work and knowledge and there are cultures that value confidence.”

A country that wants to be entertained, he says, is likely to apply low standards for leadership, preferring self-belief to caution and hard work. “Whether it’s Trump, Boris, Steve Jobs, Elon Musk – they celebrate them because they challenge the establishment. When they behave in anarchic ways, disrespecting the rules, I think they can channel the anger that people have.” The kicker is that we assume there’s some competence behind the blagging and bluster, that the emperor is fully clothed. But how do we work out if it is true: spreadsheet or gut?

There are, it seems, two types of “winging it” stories. First, there are the triumphant ones – the victories pulled, cheekily, improbably, from the jaws of defeat. Like the time a historian (who prefers to remain nameless) turned up to give a talk on one subject, only to discover her hosts were expecting, and had advertised, another. “I wrote the full thing – an hour-long show – in 10 panicked minutes,” she says. “At the end, a lady came up to congratulate me on how spontaneous my delivery was.”

Then there is the other kind of winging it story – the kind that ends in ignominy. Remember the safeguarding minister, Rachel Maclean, tying herself in factually inaccurate knots when asked about stop-and-search powers? The Australian journalist Matt Doran, who interviewed Adele without listening to her album? Or the culture secretary, Nadine Dorries, claiming Channel 4 was publicly funded, then that Channel 5 had been privatised?

There are even worse examples. As a young journalist, Sarah Dempster was unwell when she was supposed to review a Meat Loaf concert, so she wrote the piece without attending. “An hour after publication, the paper called to inform me that the gig had, in fact, been cancelled. I was sacked,” she tweeted. “The Sun wrote a piece about it. The headline: ‘MEAT OAF’.”

Why does anyone wing it, and how do they dare? As a lifelong dreary prepper, I have been wondering this since reading a profile in the New York Times of winger extraordinaire Elon Musk. “To a degree unseen in any other mogul, the entrepreneur acts on whim, fancy and the certainty that he is 100% right,” it related, detailing how Musk wings even the biggest decisions, operating on gut feeling and without a business plan, rejecting expert advice.

Genius or graft? Apple founder Steve Jobs and Zhou Qunfei, China’s richest woman. Composite: Getty/Shutterstock/Guardian Design

Genius or graft? Apple founder Steve Jobs and Zhou Qunfei, China’s richest woman. Composite: Getty/Shutterstock/Guardian DesignWhat, I wonder, is the appeal of this strategy? And is it a legitimate – indeed, more successful – way of doing business? Can Musk, the CEO of Tesla (a company with a market capitalisation of £570bn) and the founder of SpaceX (the first private company to send humans into space) really be winging it?

Some are sceptical. “Is this self-presentation or an accurate statement?” asks Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, an organisational psychologist and the author of Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? “Musk is probably way too smart to actually operate under that principle; he uses this arrogant self-presentation to his advantage. Brand Musk accounts for a big chunk of his success.” In contrast, he says, the recent Netflix SpaceX documentary shows Musk as “quite self-critical, quite humble”.

It is an idea echoed by Stefan Stern, a visiting professor at the Bayes Business School at City, University of London and the author of Myths of Management. “I can’t believe that he doesn’t draw on data; it’s a leading-edge thing he’s engaged in. When you promote yourself as a sort of visionary or hero, you absolutely want to try to claim that there’s something special about your insights – they’re not a petty, banal matter of data.”

The implication is that Musk is like those schoolkids who claim not to have done a minute’s revision, then ace the exam. There is, the argument goes, something innately appealing about someone operating effortlessly on flair, instinct and inspiration: a Steve Jobs, not a Zhou Qunfei – the discreet founder of Lens Technology and the richest woman in China, who, Chamorro-Premuzic says, credits her success to “hard work and a relentless desire to learn”.

“There’s something romantic to the idea that there are mavericks who don’t need to work very hard,” adds Chamorro-Premuzic. “We say we value hard work and dedication, but, by definition, talent is more of an extraordinary gift and we celebrate that more.”

The leadership expert Eve Poole agrees. “No one wants to make it feel like hard work,” she says. “No one wants to say: ‘I slaved in front of a spreadsheet for 20 hours before I made that decision.’”

For Stern, Boris Johnson’s apparent penchant for winging it carries a similar message. “When he says: ‘We got the big calls right,’ he’s saying: ‘These small-minded people obsess about data and numbers and statistics, but with my instinct, my judgment, I – the uniquely gifted, insightful leader – got the big calls right.’ It’s not even true!”

His self-presentation as “a charismatic figure with panache who is apparently spontaneous” is particularly interesting, Stern says, given that “the other thing we know about Johnson is he’s not spontaneous, he doesn’t have good lines off the cuff”. (See that disastrous CBI Peppa Pig speech in November, recent prime minister’s questions performances or his testy, defensive responses in more probing interviews.)

Is there any foundation for the notion that gut feeling is superior to pedestrian, data-driven decision-making? The cognitive psychologist Gary Klein has spent his career researching intuition in decision-making; 35 years on, his research on how firefighters act swiftly under pressure in tough situations is still cited. “We weren’t looking for intuition,” he says. Rather, his team’s original theory was that firefighters might be rapidly evaluating two options when they decided how to tackle a fire. “They told us: ‘We don’t compare any options.’ More than that, they said: ‘We never make any decisions.’” Klein didn’t understand how firefighters could believe only one course of action was possible and land on it without making comparisons.

Further digging revealed a different picture. With 15 to 20 years of experience, Klein explains, the firefighters were classifying the situation based on fires they had seen – a process known as “pattern matching”. The second step Klein called “mental simulation”: the firefighters would visualise how a course of action would run and adjust their model accordingly. “It’s a blend of intuition and analysis,” says Klein. The process was near-instantaneous. “Most decisions were made in less than a minute.”

So, what looks like winging it can, in fact, be instinctive decision-making backed up by experience – what Poole calls “really quick heuristics in your brain … synaptic connections established through years of conditioning”. Leaders who trust that, she says, “are just fucking excellent”.

This decision-making model is common in one of the areas where people are least comfortable with the idea of winging it: healthcare. No one wants to end up in the hands of a seat-of-the-pants neurosurgeon, but Klein’s research suggests medical professionals use intuitive decision-making and gut feeling as a matter of course.

His book The Power of Intuition tells the story of an experienced neonatal intensive care unit nurse accurately diagnosing a baby with sepsis just by walking past the incubator and getting a gut feeling, when a less experienced nurse who had been conscientiously tracking all the infant’s vitals had failed to spot it. “An experienced physician sees a cluster of cues and says sepsis. We’ve heard stories of someone who was just a resident; there was a tough case and they called the attending physician. The attending physician does not even enter the room and from the door just looks at the patient and sees there’s an issue and says: ‘Ah, congestive heart failure.’”

Firefighters in New York. Gary Klein’s research suggests they use ‘a blend of intuition and analysis’ to make quick decisions. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Firefighters in New York. Gary Klein’s research suggests they use ‘a blend of intuition and analysis’ to make quick decisions. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty ImagesThe experiences that feed intuition can be less concrete. Poole has been researching what humans still have to offer in a world in which AI is ever-more powerful, such as what she calls “witch-style intuition” – that sense of foreboding when you enter a room or meet someone. “We all know we have had those feelings and we tend to discount them and think they’re a bit silly and weird,” she says. “But I think it’s probably coming from the collective historical unconscious, trying to keep us safe as a species.” There are, she says, two strands: “your own, desperately hard-earned gut feeling, laid down in templates of data and knowledge, then the spooky ephemera that you can pick up through ‘spidey sense’, which I think can still be really reliable.”

It can, but it isn’t always. Intuition of any kind is not infallible. Klein describes it as a “data point”: something to take into consideration, not to accept uncritically. One area in which intuition gives demonstrably poor outcomes is recruitment. As Chamorro-Premuzic explains, unstructured interview processes increase and reinforce conscious and unconscious biases about candidates. We all believe our own intuition to be superior, he says: “In an interview situation, this is a big problem, because hiring managers think they have an ability to see through candidates and to understand whether they are competent.” Companies will spend large budgets on diversity and inclusion, “then tell you they hire for ‘culture fit’ – and the main way to evaluate culture fit is whether somebody ‘feels right’ in a job interview. Even if managers are well-meaning and open-minded, they will gravitate towards candidates who are like them and they are comfortable with.”

Moreover, studies show that people tend to make up their mind in the first 60 or 90 seconds, he says. This is pattern recognition gone wrong, according to Stern. When decision-makers see someone who reminds them of themselves, they think: “Oh yeah, he’s got the right stuff. I used to be like him.”

Donald Trump springs to mind here. I read Klein a typical Trump pronouncement: “I have a gut and my gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me.” It reminds Klein of two dangerous fallacies about intuition: “One, some people think intuition is innate ability, which I don’t think it is; it’s based on experience. Two, intuition is a general skill and will apply in lots of different situations. I don’t think that’s true.” Having decent intuition in an area where you have professional experience – “like real estate”, he says, pointedly – does not mean you have a transferable skill.

Talking to people who admit to winging it reveals that, mainly, they mean the “good” kind of intuition: calling on a wealth of relevant experience and deploying it in defined circumstances. That often involves an element of performance, where spontaneity can be the secret ingredient.

Susannah, who works in publishing, says: “I love to wing it in sales presentations. When I wing it, I suddenly find a new angle; it works every time. But only, I think, because I’m winging stuff I already know deeply.” Kathy, a senior financial services strategist, says: “If it’s something I don’t know at all, I won’t wing it, but in my area of expertise I’m the queen of prep five minutes before the meeting.”

These are the good wingers, but of course the bad ones are out there – the lazy, the grandiose blaggers and the bullshitters, too often in positions of power. “There are a lot of men, particularly, who do that,” says Poole. “I think it does appeal to people who don’t feel anything any more – it’s all so boring and that’s the way they get some feelings. It gives them a massive adrenaline rush; it makes them feel very powerful and victorious.” It is not usually a successful long-term strategy, she adds, comfortingly; what Chamorro-Premuzic calls “the sense of Teflon-style immunity” betrays them eventually. “I just think you get caught out. It’s the spin of the wheel and that’s why I hate it: it’s so risky for your organisation.”

But we still admire them, buy their products, even vote for them. Why do we fall for it? It is a lack of “followership maturity”, according to Chamorro-Premuzic, and varies from culture to culture. “I grew up in South America, where if you work hard and you succeed you’re automatically a loser,” he says. “Whereas if you bullshit and deceive people, we should worship you. There are cultures that truly value self-improvement, hard work and knowledge and there are cultures that value confidence.”

A country that wants to be entertained, he says, is likely to apply low standards for leadership, preferring self-belief to caution and hard work. “Whether it’s Trump, Boris, Steve Jobs, Elon Musk – they celebrate them because they challenge the establishment. When they behave in anarchic ways, disrespecting the rules, I think they can channel the anger that people have.” The kicker is that we assume there’s some competence behind the blagging and bluster, that the emperor is fully clothed. But how do we work out if it is true: spreadsheet or gut?

Tuesday, 31 August 2021

Thursday, 6 May 2021

Sunday, 24 May 2020

Thursday, 7 November 2019

I was an astrologer – here's how it really works, and why I had to stop

Customers marvelled at my psychic abilities but was that really what was going on when I told their fortune? asks Felicity Carter in The Guardian

FacebookTwitterPinterest ‘The range of problems faced by people who can afford $50 for fortune telling turned out to be limited: troubles with romance, troubles at work, trouble mustering the courage for a much-needed change.’ Photograph: Busà Photography/Getty Images

To test my new skills, I volunteered to be a clairvoyant at the spiritualist church. Congregants would place a flower on the table, and the clairvoyants would choose one and “read” it at the microphone. Nervous, the first thing I grabbed was a packet of silver foil. The rose inside had been packed so tightly, its petals were crushed. I didn’t get a single vibe from it, so I just described the symbolism.

“You are feeling battered and bruised,” I said.

Afterwards, a woman approached and said she was a victim of domestic violence, and what should she do?

I was only 19 and had no idea, but my psychic reputation soared. The attention was intoxicating.

Then the universe told me I wasn’t cut out for science, by sending me my second-year results. I dropped out to pursue theatre and also signed up for a one-year course at the Sydney Astrology Centre, a cavernous commercial building in a seedy part of town.

The course began with the meanings of the zodiac, from Aries to Aquarius. Then the luminaries; the sun (what you will become), the moon (what you brought into this life) and planets. After that, how to calculate planetary positions and cast horoscopes.

Although astrologers use Nasa data for their calculations, horoscopes aren’t a true map of the heavens. The Babylonians who invented astrology believed the sun rotated round the Earth; modern astrologers still use Earth-centred charts, as if Copernicus had never existed. That’s only the start of the scientific problems.

The astrological meanings themselves derive from a principle called sympathetic magic, where things that look alike are linked together. Mars looks red, so it rules red things like blood. How do you get blood? You cut, so Mars rules surgery and war.

You forecast by combining meanings with planetary movements. Say Saturn, planet of restrictions, is about to transit the First House of self – your life will contract! You’re going to get more responsibilities than usual. Or maybe you’ll be denied the chance to take on more responsibilities. Or maybe a cold, critical person will come into your life. But anyway, it’s a good time to go on a diet.

Astrology is one big word association game.

I loved it, though I was losing interest in other mystical practices. Partly I didn’t have time, because I was now immersed in theatre while working as a temp typist at St Vincent’s, a Catholic hospital. But as I bounced from one department to another, my views changed. I’d understood organised religion to be something between an embarrassment and an evil. Yet as Aids did its dreadful work – this was the 1990s – I watched nuns offer compassionate care to the dying. Christian volunteers checked on derelict men with vomit down their clothes. I became uncomfortably aware that New Agers do not build hospitals or feed alcoholics – they buy self-actualisation at the cash register.

Finally, I was accepted into a music degree and my days filled with classes, my nights with rehearsals. This caused a cash crisis, because I could only do office work during academic holidays. When I saw the ad for a fortune teller, I pounced.

My credentials impressed the man on the counter (“My name is Ron,” he said. “My spirit guide is Blue Star. He’s on the intergalactic committee”) and I was hired.

We charged A$50 an hour, a significant sum at the time, and I wanted to offer value. No fishing for clues from me – I printed a horoscope or laid the cards and started interpreting immediately, intending to dazzle the customer with my insights.

Half the time, though, I couldn’t get a word in. It turned out what most people want is the chance to unload for an hour.

The range of problems faced by people who can afford $50 for fortune telling turned out to be limited: troubles with romance, troubles at work, trouble mustering the courage for a much-needed change. I heard these stories so often I could often guess what the problem was the moment someone walked in. Heartbroken young men, for example, talk about it to psychics, because it’s less risky than telling their friends. Sometimes I’d mischievously say, “Let her go. She’s not worth it,” as soon as one arrived. Once I heard, “Oh my God, oh my GOD!” as an amazed guy fell backwards down the stairs.

I also learned that intelligence and education do not protect against superstition. Many customers were stockbrokers, advertising executives or politicians, dealing with issues whose outcomes couldn’t be controlled. It’s uncertainty that drives people into woo, not stupidity, so I’m not surprised millennials are into astrology. They grew up with Harry Potter and graduated into a precarious economy, making them the ideal customers.

FacebookTwitterPinterest ‘Intelligence and education do not protect against superstition.’ Photograph: Alamy

What broke the spell for me was, oddly, people swearing by my gift. Some repeat customers claimed I’d made very specific predictions, of a kind I never made. It dawned on me that my readings were a co-creation – I would weave a story and, later, the customer’s memory would add new elements. I got to test this theory after a friend raved about a reading she’d had, full of astonishingly accurate predictions. She had a tape of the session, so I asked her to play it.

The clairvoyant had said none of the things my friend claimed. Not a single one. My friend’s imagination had done all the work.

Yet sometimes I could be uncannily accurate – wasn’t that proof I was psychic? One Sunday, I went straight from work to a party, before I’d had time to shuck off my psychic persona. A student there mentioned she wasn’t sure what to specialize in – photography, graphic design or maybe industrial design?

“Do photography,” I said.

She looked at me, wide-eyed. “How did you know?” she said, explaining photography was her real love, but her parents didn’t approve.

I couldn’t say, “because my third eye is open”, so I reflected for a moment. Then it hit me. “You sounded happier when you said ‘photography’,” I said. My psychic teacher was right – the signals we pick up before conscious awareness kicks in can be accurate and valuable.

Well, maybe I wasn’t psychic, but it didn’t matter. It was just entertainment, after all, until the cursed man came in. The one who’d seen the Catholic priest.

“Get to a doctor,” I told him. “Now.”

That very week, I’d typed letters for a neurologist who specialized in brain diseases. Some of those letters had documented strikingly similar symptoms to this man.

“Are you saying I’m crazy?” he said, his hands balled.

“No,” I reassured him. “But Catholic priests know what they’re doing. If he couldn’t help, this isn’t a curse.”

That made the man angrier.

“You’re a fraud!” he shouted, and stormed downstairs to demand his money back.

The encounter shook me, badly. Shortly afterwards, I packed my astrology books and Tarot cards away for good.

I can still make the odd forecast, though. Here’s one: the venture capital pouring into astrology apps will create a fortune telling system that works, because humans are predictable. As people follow the advice, the apps’ predictive powers will increase, creating an ever-tighter electronic leash. But they’ll be hugely popular – because if you sprinkle magic on top, you can sell people anything.

‘It turned out what most people want is the chance to unload for an hour.’ Photograph: Fiorella Macor/Getty Images

The man was agitated, with red-rimmed eyes and clammy skin.

“Help me,” he said. “I’m under a curse.”

At first it was just flickering lights, he said. And then a figure, at the edge of his vision. Now something grabbed his fingers or stroked his arm. There was more – and it was happening more frequently.

“I saw a Catholic priest,” said the man. “But he couldn’t help. Can you?”

Yes, yes I could. I knew exactly what he needed to do.

I was a fortune teller. Every Sunday, I climbed the stairs of an old terrace house in Sydney’s historic Rocks district, to sit in the attic and divine the future. I would read Tarot cards or interpret horoscopes.

As a teenager, I’d devoured a book called Positive Magic. An instruction manual for witches, its central idea was that if you wanted something, and you had good intentions, you just told the universe and magic would happen. Although nothing I wanted (fame, money, hot boyfriend) actually arrived, one thing led to another and I taught myself to read Tarot cards. At the time I was a science student, and just considered it a fun game at parties.

That changed after I took my cards to my part-time job and read them for a colleague during the break. She picked the card for pregnancy, which we laughed about, because she wanted her tubes tied.

A week later she said, “Guess what the doctor told me this morning?”

She was pregnant, and I was officially psychic.

Deciding to develop my gift, I enrolled in a psychic class, where I learned to say the first thing that popped into my head. “Your first thoughts are the most psychic ones, before your rational mind interferes,” said the teacher.

I also learned that all things are connected, and everything is a symbol of something else. Suddenly, I saw signs and omens everywhere.

The man was agitated, with red-rimmed eyes and clammy skin.

“Help me,” he said. “I’m under a curse.”

At first it was just flickering lights, he said. And then a figure, at the edge of his vision. Now something grabbed his fingers or stroked his arm. There was more – and it was happening more frequently.

“I saw a Catholic priest,” said the man. “But he couldn’t help. Can you?”

Yes, yes I could. I knew exactly what he needed to do.

I was a fortune teller. Every Sunday, I climbed the stairs of an old terrace house in Sydney’s historic Rocks district, to sit in the attic and divine the future. I would read Tarot cards or interpret horoscopes.

As a teenager, I’d devoured a book called Positive Magic. An instruction manual for witches, its central idea was that if you wanted something, and you had good intentions, you just told the universe and magic would happen. Although nothing I wanted (fame, money, hot boyfriend) actually arrived, one thing led to another and I taught myself to read Tarot cards. At the time I was a science student, and just considered it a fun game at parties.

That changed after I took my cards to my part-time job and read them for a colleague during the break. She picked the card for pregnancy, which we laughed about, because she wanted her tubes tied.

A week later she said, “Guess what the doctor told me this morning?”

She was pregnant, and I was officially psychic.

Deciding to develop my gift, I enrolled in a psychic class, where I learned to say the first thing that popped into my head. “Your first thoughts are the most psychic ones, before your rational mind interferes,” said the teacher.

I also learned that all things are connected, and everything is a symbol of something else. Suddenly, I saw signs and omens everywhere.

FacebookTwitterPinterest ‘The range of problems faced by people who can afford $50 for fortune telling turned out to be limited: troubles with romance, troubles at work, trouble mustering the courage for a much-needed change.’ Photograph: Busà Photography/Getty Images

To test my new skills, I volunteered to be a clairvoyant at the spiritualist church. Congregants would place a flower on the table, and the clairvoyants would choose one and “read” it at the microphone. Nervous, the first thing I grabbed was a packet of silver foil. The rose inside had been packed so tightly, its petals were crushed. I didn’t get a single vibe from it, so I just described the symbolism.

“You are feeling battered and bruised,” I said.

Afterwards, a woman approached and said she was a victim of domestic violence, and what should she do?

I was only 19 and had no idea, but my psychic reputation soared. The attention was intoxicating.

Then the universe told me I wasn’t cut out for science, by sending me my second-year results. I dropped out to pursue theatre and also signed up for a one-year course at the Sydney Astrology Centre, a cavernous commercial building in a seedy part of town.

The course began with the meanings of the zodiac, from Aries to Aquarius. Then the luminaries; the sun (what you will become), the moon (what you brought into this life) and planets. After that, how to calculate planetary positions and cast horoscopes.

Although astrologers use Nasa data for their calculations, horoscopes aren’t a true map of the heavens. The Babylonians who invented astrology believed the sun rotated round the Earth; modern astrologers still use Earth-centred charts, as if Copernicus had never existed. That’s only the start of the scientific problems.

The astrological meanings themselves derive from a principle called sympathetic magic, where things that look alike are linked together. Mars looks red, so it rules red things like blood. How do you get blood? You cut, so Mars rules surgery and war.

You forecast by combining meanings with planetary movements. Say Saturn, planet of restrictions, is about to transit the First House of self – your life will contract! You’re going to get more responsibilities than usual. Or maybe you’ll be denied the chance to take on more responsibilities. Or maybe a cold, critical person will come into your life. But anyway, it’s a good time to go on a diet.

Astrology is one big word association game.

I loved it, though I was losing interest in other mystical practices. Partly I didn’t have time, because I was now immersed in theatre while working as a temp typist at St Vincent’s, a Catholic hospital. But as I bounced from one department to another, my views changed. I’d understood organised religion to be something between an embarrassment and an evil. Yet as Aids did its dreadful work – this was the 1990s – I watched nuns offer compassionate care to the dying. Christian volunteers checked on derelict men with vomit down their clothes. I became uncomfortably aware that New Agers do not build hospitals or feed alcoholics – they buy self-actualisation at the cash register.

Finally, I was accepted into a music degree and my days filled with classes, my nights with rehearsals. This caused a cash crisis, because I could only do office work during academic holidays. When I saw the ad for a fortune teller, I pounced.

My credentials impressed the man on the counter (“My name is Ron,” he said. “My spirit guide is Blue Star. He’s on the intergalactic committee”) and I was hired.

We charged A$50 an hour, a significant sum at the time, and I wanted to offer value. No fishing for clues from me – I printed a horoscope or laid the cards and started interpreting immediately, intending to dazzle the customer with my insights.

Half the time, though, I couldn’t get a word in. It turned out what most people want is the chance to unload for an hour.

The range of problems faced by people who can afford $50 for fortune telling turned out to be limited: troubles with romance, troubles at work, trouble mustering the courage for a much-needed change. I heard these stories so often I could often guess what the problem was the moment someone walked in. Heartbroken young men, for example, talk about it to psychics, because it’s less risky than telling their friends. Sometimes I’d mischievously say, “Let her go. She’s not worth it,” as soon as one arrived. Once I heard, “Oh my God, oh my GOD!” as an amazed guy fell backwards down the stairs.

I also learned that intelligence and education do not protect against superstition. Many customers were stockbrokers, advertising executives or politicians, dealing with issues whose outcomes couldn’t be controlled. It’s uncertainty that drives people into woo, not stupidity, so I’m not surprised millennials are into astrology. They grew up with Harry Potter and graduated into a precarious economy, making them the ideal customers.

FacebookTwitterPinterest ‘Intelligence and education do not protect against superstition.’ Photograph: Alamy

What broke the spell for me was, oddly, people swearing by my gift. Some repeat customers claimed I’d made very specific predictions, of a kind I never made. It dawned on me that my readings were a co-creation – I would weave a story and, later, the customer’s memory would add new elements. I got to test this theory after a friend raved about a reading she’d had, full of astonishingly accurate predictions. She had a tape of the session, so I asked her to play it.

The clairvoyant had said none of the things my friend claimed. Not a single one. My friend’s imagination had done all the work.

Yet sometimes I could be uncannily accurate – wasn’t that proof I was psychic? One Sunday, I went straight from work to a party, before I’d had time to shuck off my psychic persona. A student there mentioned she wasn’t sure what to specialize in – photography, graphic design or maybe industrial design?

“Do photography,” I said.

She looked at me, wide-eyed. “How did you know?” she said, explaining photography was her real love, but her parents didn’t approve.

I couldn’t say, “because my third eye is open”, so I reflected for a moment. Then it hit me. “You sounded happier when you said ‘photography’,” I said. My psychic teacher was right – the signals we pick up before conscious awareness kicks in can be accurate and valuable.

Well, maybe I wasn’t psychic, but it didn’t matter. It was just entertainment, after all, until the cursed man came in. The one who’d seen the Catholic priest.

“Get to a doctor,” I told him. “Now.”

That very week, I’d typed letters for a neurologist who specialized in brain diseases. Some of those letters had documented strikingly similar symptoms to this man.

“Are you saying I’m crazy?” he said, his hands balled.

“No,” I reassured him. “But Catholic priests know what they’re doing. If he couldn’t help, this isn’t a curse.”

That made the man angrier.

“You’re a fraud!” he shouted, and stormed downstairs to demand his money back.

The encounter shook me, badly. Shortly afterwards, I packed my astrology books and Tarot cards away for good.

I can still make the odd forecast, though. Here’s one: the venture capital pouring into astrology apps will create a fortune telling system that works, because humans are predictable. As people follow the advice, the apps’ predictive powers will increase, creating an ever-tighter electronic leash. But they’ll be hugely popular – because if you sprinkle magic on top, you can sell people anything.

Wednesday, 27 February 2019

Why do so many incompetent men win at work?

Emma Jacobs in The FT

“Women are better leaders,” says Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic. “I am not neutral on this. I am sexist in favour of women. Women have better people skills, more altruistic, better able to control their impulses. They outperform men in university at graduate and undergraduate levels.”

This subject is explored in his new book, Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? (And How to Fix It). In it, he writes that “traits like overconfidence and self-absorption should be seen as red flags”, when, in fact, the opposite tends to happen. As Prof Chamorro-Premuzic puts it: “They prompt us to say: ‘Ah, there’s a charismatic fellow! He’s probably leadership material.’”

It is this mistaken insistence that confidence equates to greatness that is the reason so many ill-suited men get top jobs, he argues. “The result in both business and politics is a surplus of incompetent men in charge, and this surplus reduces opportunities for competent people — women and men — while keeping the standards of leadership depressingly low.”

This book is based on a Harvard Business Review blog of the same title which was published in 2013, and which elicited more feedback than any of his previous books or articles. He is currently professor of business psychology at University College London and at Columbia University, as well as being the “chief talent scientist” at Manpower Group and co-founder of two companies that deploy technological tools to enhance staff retention. This book builds on two of his professional interests: data and confidence.

Too often, he argues, we use intuition rather than metrics to judge whether someone is competent. In his book he argues that confidence may well be a “compensatory strategy for lower competence”. The modern mantra to just believe in yourself is possibly foolish. Perhaps, he suggests, modesty is not false but an accurate awareness of one’s talents and limitations.

The book’s title has been “too provocative” for many, Prof Chamorro-Premuzic tells me on the phone from Brooklyn, where he spends most of his time, juggling his teaching and corporate roles. “A lot of female leaders said they can’t endorse it as [they are] worried about looking like man-haters.” Some female colleagues feel depressed that his message is being heard because he is a man, whereas if it came from them it would be “dismissed”. Men criticise him for “virtue-signalling”.

He makes a convincing case for a more modest style of leader, focused on the team rather than advancing their own careers. Angela Merkel is the “most boring and best leader” in politics, he says. In the corporate sphere, he picks Warren Buffett who, he says, started off as a finance geek and taught himself leadership skills. David Cameron, the former British prime minister, is cited as an example of misplaced confidence in a leader — he held a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU, sure that he would win, an assurance that, as it turned out, was misplaced.

A quiet leadership style is often overlooked as heads are turned by bravado and narcissism. “There is a cult of confidence,” says Prof Chamorro-Premuzic. In part this is because confidence is “easier to observe”. It is harder to discern whether someone is a good leader. “What we see is what we rely on, what we see is visible.”

People “overrate their intuition”, he says. Too often it turns out to be “nepotistic, self-serving choices . . . most organisations don’t have data to tell you if the leader is good.”

Those leaders who are celebrated for their volatility and short fuses, such as the late Apple boss Steve Jobs, might have succeeded despite, not because of, their personality defects, he argues.

One common narrative holds that women are held back by a lack of confidence, yet studies show this to be a fallacy. Perhaps it would be better to say that they are less likely to overrate themselves. The book cites one study from Columbia University which found that men overstated their maths ability by 30 per cent and women by 15 per cent.

It is also the case, he writes, that women are penalised for appearing confident: “Their mistakes are judged more harshly and remembered longer. Their behaviour is scrutinised more carefully and their colleagues are less likely to share vital information with them. When women speak, they’re more likely to be interrupted or ignored.”

“The fundamental role of self-confidence is not to be as high as possible,” he adds, “but to be in sync with ability.”

Prof Chamorro-Premuzic’s interest in leadership was nurtured while growing up in Argentina, a country that he describes as having had one terrible leader after another. He came from a pocket of Buenos Aires known as Villa Freud for its high concentration of psychotherapists (even his family dog had a therapist), so it was a natural step to enter the field of psychology.

There are many observations in the book that posit women as the superior sex, for example, citing their higher emotional intelligence. Such biological essentialism has been contested, for example by Cordelia Fine in her book Testosterone Rex: Unmaking the Myths of Our Gendered Minds.

Prof Chamorro-Premuzic says describing such differences as “hard-wired” would be an “overstatement”. Nonetheless, he argues that men score higher for impulsivity, risk-taking, narcissism, aggression and overconfidence; while women do better on emotional intelligence, empathy, altruism, self-awareness and humility.

The book’s central message, though, is not to make a case for preferential treatment for women, but rather to “elevate the standards of leadership”. We should be making it harder for terrible men to get to the top, rather than focusing solely on removing the hurdles for women.

He makes the argument against setting quotas for women in senior positions, which, Prof Chamorro-Premuzic says, can look like special pleading. Rather, he says: “We should minimise biases when it comes to evaluating leaders, rely less and less on human valuations and use performance data.”

Raising the leadership game will boost the number of women in such positions, but it will also highlight talented but modest men who are typically overlooked. “There are many competent men who are being disregarded for leadership roles,” he says. “They don’t float hypermasculine leadership roles.”

“Women are better leaders,” says Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic. “I am not neutral on this. I am sexist in favour of women. Women have better people skills, more altruistic, better able to control their impulses. They outperform men in university at graduate and undergraduate levels.”

This subject is explored in his new book, Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? (And How to Fix It). In it, he writes that “traits like overconfidence and self-absorption should be seen as red flags”, when, in fact, the opposite tends to happen. As Prof Chamorro-Premuzic puts it: “They prompt us to say: ‘Ah, there’s a charismatic fellow! He’s probably leadership material.’”

It is this mistaken insistence that confidence equates to greatness that is the reason so many ill-suited men get top jobs, he argues. “The result in both business and politics is a surplus of incompetent men in charge, and this surplus reduces opportunities for competent people — women and men — while keeping the standards of leadership depressingly low.”

This book is based on a Harvard Business Review blog of the same title which was published in 2013, and which elicited more feedback than any of his previous books or articles. He is currently professor of business psychology at University College London and at Columbia University, as well as being the “chief talent scientist” at Manpower Group and co-founder of two companies that deploy technological tools to enhance staff retention. This book builds on two of his professional interests: data and confidence.