There are, it seems, two types of “winging it” stories. First, there are the triumphant ones – the victories pulled, cheekily, improbably, from the jaws of defeat. Like the time a historian (who prefers to remain nameless) turned up to give a talk on one subject, only to discover her hosts were expecting, and had advertised, another. “I wrote the full thing – an hour-long show – in 10 panicked minutes,” she says. “At the end, a lady came up to congratulate me on how spontaneous my delivery was.”

Then there is the other kind of winging it story – the kind that ends in ignominy. Remember the safeguarding minister, Rachel Maclean, tying herself in factually inaccurate knots when asked about stop-and-search powers? The Australian journalist Matt Doran, who interviewed Adele without listening to her album? Or the culture secretary, Nadine Dorries, claiming Channel 4 was publicly funded, then that Channel 5 had been privatised?

There are even worse examples. As a young journalist, Sarah Dempster was unwell when she was supposed to review a Meat Loaf concert, so she wrote the piece without attending. “An hour after publication, the paper called to inform me that the gig had, in fact, been cancelled. I was sacked,” she tweeted. “The Sun wrote a piece about it. The headline: ‘MEAT OAF’.”

Why does anyone wing it, and how do they dare? As a lifelong dreary prepper, I have been wondering this since reading a profile in the New York Times of winger extraordinaire Elon Musk. “To a degree unseen in any other mogul, the entrepreneur acts on whim, fancy and the certainty that he is 100% right,” it related, detailing how Musk wings even the biggest decisions, operating on gut feeling and without a business plan, rejecting expert advice.

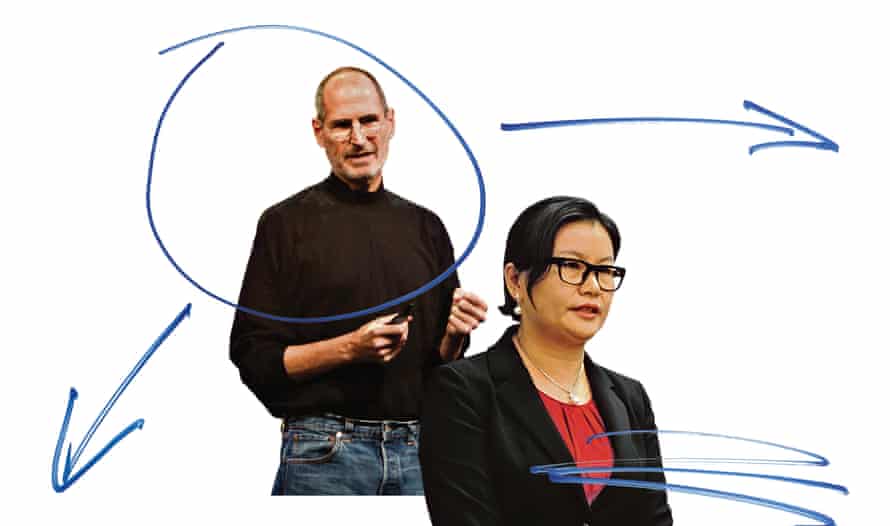

Genius or graft? Apple founder Steve Jobs and Zhou Qunfei, China’s richest woman. Composite: Getty/Shutterstock/Guardian Design

Genius or graft? Apple founder Steve Jobs and Zhou Qunfei, China’s richest woman. Composite: Getty/Shutterstock/Guardian DesignWhat, I wonder, is the appeal of this strategy? And is it a legitimate – indeed, more successful – way of doing business? Can Musk, the CEO of Tesla (a company with a market capitalisation of £570bn) and the founder of SpaceX (the first private company to send humans into space) really be winging it?

Some are sceptical. “Is this self-presentation or an accurate statement?” asks Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, an organisational psychologist and the author of Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? “Musk is probably way too smart to actually operate under that principle; he uses this arrogant self-presentation to his advantage. Brand Musk accounts for a big chunk of his success.” In contrast, he says, the recent Netflix SpaceX documentary shows Musk as “quite self-critical, quite humble”.

It is an idea echoed by Stefan Stern, a visiting professor at the Bayes Business School at City, University of London and the author of Myths of Management. “I can’t believe that he doesn’t draw on data; it’s a leading-edge thing he’s engaged in. When you promote yourself as a sort of visionary or hero, you absolutely want to try to claim that there’s something special about your insights – they’re not a petty, banal matter of data.”

The implication is that Musk is like those schoolkids who claim not to have done a minute’s revision, then ace the exam. There is, the argument goes, something innately appealing about someone operating effortlessly on flair, instinct and inspiration: a Steve Jobs, not a Zhou Qunfei – the discreet founder of Lens Technology and the richest woman in China, who, Chamorro-Premuzic says, credits her success to “hard work and a relentless desire to learn”.

“There’s something romantic to the idea that there are mavericks who don’t need to work very hard,” adds Chamorro-Premuzic. “We say we value hard work and dedication, but, by definition, talent is more of an extraordinary gift and we celebrate that more.”

The leadership expert Eve Poole agrees. “No one wants to make it feel like hard work,” she says. “No one wants to say: ‘I slaved in front of a spreadsheet for 20 hours before I made that decision.’”

For Stern, Boris Johnson’s apparent penchant for winging it carries a similar message. “When he says: ‘We got the big calls right,’ he’s saying: ‘These small-minded people obsess about data and numbers and statistics, but with my instinct, my judgment, I – the uniquely gifted, insightful leader – got the big calls right.’ It’s not even true!”

His self-presentation as “a charismatic figure with panache who is apparently spontaneous” is particularly interesting, Stern says, given that “the other thing we know about Johnson is he’s not spontaneous, he doesn’t have good lines off the cuff”. (See that disastrous CBI Peppa Pig speech in November, recent prime minister’s questions performances or his testy, defensive responses in more probing interviews.)

Is there any foundation for the notion that gut feeling is superior to pedestrian, data-driven decision-making? The cognitive psychologist Gary Klein has spent his career researching intuition in decision-making; 35 years on, his research on how firefighters act swiftly under pressure in tough situations is still cited. “We weren’t looking for intuition,” he says. Rather, his team’s original theory was that firefighters might be rapidly evaluating two options when they decided how to tackle a fire. “They told us: ‘We don’t compare any options.’ More than that, they said: ‘We never make any decisions.’” Klein didn’t understand how firefighters could believe only one course of action was possible and land on it without making comparisons.

Further digging revealed a different picture. With 15 to 20 years of experience, Klein explains, the firefighters were classifying the situation based on fires they had seen – a process known as “pattern matching”. The second step Klein called “mental simulation”: the firefighters would visualise how a course of action would run and adjust their model accordingly. “It’s a blend of intuition and analysis,” says Klein. The process was near-instantaneous. “Most decisions were made in less than a minute.”

So, what looks like winging it can, in fact, be instinctive decision-making backed up by experience – what Poole calls “really quick heuristics in your brain … synaptic connections established through years of conditioning”. Leaders who trust that, she says, “are just fucking excellent”.

This decision-making model is common in one of the areas where people are least comfortable with the idea of winging it: healthcare. No one wants to end up in the hands of a seat-of-the-pants neurosurgeon, but Klein’s research suggests medical professionals use intuitive decision-making and gut feeling as a matter of course.

His book The Power of Intuition tells the story of an experienced neonatal intensive care unit nurse accurately diagnosing a baby with sepsis just by walking past the incubator and getting a gut feeling, when a less experienced nurse who had been conscientiously tracking all the infant’s vitals had failed to spot it. “An experienced physician sees a cluster of cues and says sepsis. We’ve heard stories of someone who was just a resident; there was a tough case and they called the attending physician. The attending physician does not even enter the room and from the door just looks at the patient and sees there’s an issue and says: ‘Ah, congestive heart failure.’”

Firefighters in New York. Gary Klein’s research suggests they use ‘a blend of intuition and analysis’ to make quick decisions. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Firefighters in New York. Gary Klein’s research suggests they use ‘a blend of intuition and analysis’ to make quick decisions. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty ImagesThe experiences that feed intuition can be less concrete. Poole has been researching what humans still have to offer in a world in which AI is ever-more powerful, such as what she calls “witch-style intuition” – that sense of foreboding when you enter a room or meet someone. “We all know we have had those feelings and we tend to discount them and think they’re a bit silly and weird,” she says. “But I think it’s probably coming from the collective historical unconscious, trying to keep us safe as a species.” There are, she says, two strands: “your own, desperately hard-earned gut feeling, laid down in templates of data and knowledge, then the spooky ephemera that you can pick up through ‘spidey sense’, which I think can still be really reliable.”

It can, but it isn’t always. Intuition of any kind is not infallible. Klein describes it as a “data point”: something to take into consideration, not to accept uncritically. One area in which intuition gives demonstrably poor outcomes is recruitment. As Chamorro-Premuzic explains, unstructured interview processes increase and reinforce conscious and unconscious biases about candidates. We all believe our own intuition to be superior, he says: “In an interview situation, this is a big problem, because hiring managers think they have an ability to see through candidates and to understand whether they are competent.” Companies will spend large budgets on diversity and inclusion, “then tell you they hire for ‘culture fit’ – and the main way to evaluate culture fit is whether somebody ‘feels right’ in a job interview. Even if managers are well-meaning and open-minded, they will gravitate towards candidates who are like them and they are comfortable with.”

Moreover, studies show that people tend to make up their mind in the first 60 or 90 seconds, he says. This is pattern recognition gone wrong, according to Stern. When decision-makers see someone who reminds them of themselves, they think: “Oh yeah, he’s got the right stuff. I used to be like him.”

Donald Trump springs to mind here. I read Klein a typical Trump pronouncement: “I have a gut and my gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me.” It reminds Klein of two dangerous fallacies about intuition: “One, some people think intuition is innate ability, which I don’t think it is; it’s based on experience. Two, intuition is a general skill and will apply in lots of different situations. I don’t think that’s true.” Having decent intuition in an area where you have professional experience – “like real estate”, he says, pointedly – does not mean you have a transferable skill.

Talking to people who admit to winging it reveals that, mainly, they mean the “good” kind of intuition: calling on a wealth of relevant experience and deploying it in defined circumstances. That often involves an element of performance, where spontaneity can be the secret ingredient.

Susannah, who works in publishing, says: “I love to wing it in sales presentations. When I wing it, I suddenly find a new angle; it works every time. But only, I think, because I’m winging stuff I already know deeply.” Kathy, a senior financial services strategist, says: “If it’s something I don’t know at all, I won’t wing it, but in my area of expertise I’m the queen of prep five minutes before the meeting.”

These are the good wingers, but of course the bad ones are out there – the lazy, the grandiose blaggers and the bullshitters, too often in positions of power. “There are a lot of men, particularly, who do that,” says Poole. “I think it does appeal to people who don’t feel anything any more – it’s all so boring and that’s the way they get some feelings. It gives them a massive adrenaline rush; it makes them feel very powerful and victorious.” It is not usually a successful long-term strategy, she adds, comfortingly; what Chamorro-Premuzic calls “the sense of Teflon-style immunity” betrays them eventually. “I just think you get caught out. It’s the spin of the wheel and that’s why I hate it: it’s so risky for your organisation.”

But we still admire them, buy their products, even vote for them. Why do we fall for it? It is a lack of “followership maturity”, according to Chamorro-Premuzic, and varies from culture to culture. “I grew up in South America, where if you work hard and you succeed you’re automatically a loser,” he says. “Whereas if you bullshit and deceive people, we should worship you. There are cultures that truly value self-improvement, hard work and knowledge and there are cultures that value confidence.”

A country that wants to be entertained, he says, is likely to apply low standards for leadership, preferring self-belief to caution and hard work. “Whether it’s Trump, Boris, Steve Jobs, Elon Musk – they celebrate them because they challenge the establishment. When they behave in anarchic ways, disrespecting the rules, I think they can channel the anger that people have.” The kicker is that we assume there’s some competence behind the blagging and bluster, that the emperor is fully clothed. But how do we work out if it is true: spreadsheet or gut?