'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label hard. Show all posts

Showing posts with label hard. Show all posts

Saturday, 24 December 2022

Friday, 16 September 2022

Thursday, 16 June 2022

‘If you work hard and succeed, you’re a loser’: can you really wing it to the top?

Forget the spreadsheets and make it up as you go along – that’s the message of leaders from Elon Musk to Boris Johnson. But is acting on instinct really a good idea? Emma Beddington in The Guardian

There are, it seems, two types of “winging it” stories. First, there are the triumphant ones – the victories pulled, cheekily, improbably, from the jaws of defeat. Like the time a historian (who prefers to remain nameless) turned up to give a talk on one subject, only to discover her hosts were expecting, and had advertised, another. “I wrote the full thing – an hour-long show – in 10 panicked minutes,” she says. “At the end, a lady came up to congratulate me on how spontaneous my delivery was.”

Then there is the other kind of winging it story – the kind that ends in ignominy. Remember the safeguarding minister, Rachel Maclean, tying herself in factually inaccurate knots when asked about stop-and-search powers? The Australian journalist Matt Doran, who interviewed Adele without listening to her album? Or the culture secretary, Nadine Dorries, claiming Channel 4 was publicly funded, then that Channel 5 had been privatised?

There are even worse examples. As a young journalist, Sarah Dempster was unwell when she was supposed to review a Meat Loaf concert, so she wrote the piece without attending. “An hour after publication, the paper called to inform me that the gig had, in fact, been cancelled. I was sacked,” she tweeted. “The Sun wrote a piece about it. The headline: ‘MEAT OAF’.”

Why does anyone wing it, and how do they dare? As a lifelong dreary prepper, I have been wondering this since reading a profile in the New York Times of winger extraordinaire Elon Musk. “To a degree unseen in any other mogul, the entrepreneur acts on whim, fancy and the certainty that he is 100% right,” it related, detailing how Musk wings even the biggest decisions, operating on gut feeling and without a business plan, rejecting expert advice.

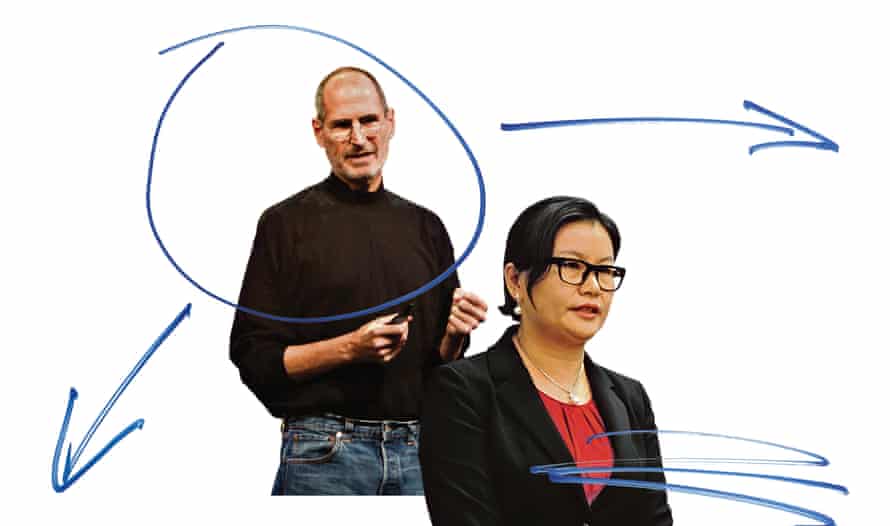

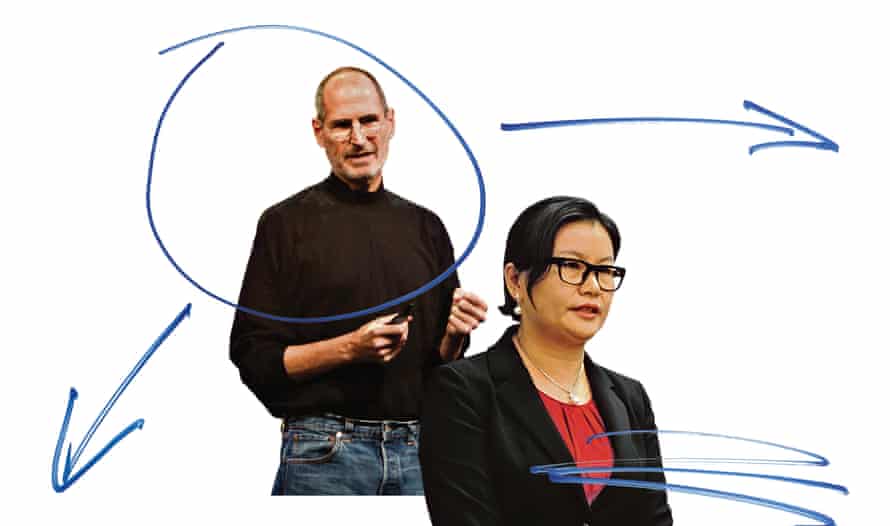

Genius or graft? Apple founder Steve Jobs and Zhou Qunfei, China’s richest woman. Composite: Getty/Shutterstock/Guardian Design

Genius or graft? Apple founder Steve Jobs and Zhou Qunfei, China’s richest woman. Composite: Getty/Shutterstock/Guardian Design

What, I wonder, is the appeal of this strategy? And is it a legitimate – indeed, more successful – way of doing business? Can Musk, the CEO of Tesla (a company with a market capitalisation of £570bn) and the founder of SpaceX (the first private company to send humans into space) really be winging it?

Some are sceptical. “Is this self-presentation or an accurate statement?” asks Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, an organisational psychologist and the author of Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? “Musk is probably way too smart to actually operate under that principle; he uses this arrogant self-presentation to his advantage. Brand Musk accounts for a big chunk of his success.” In contrast, he says, the recent Netflix SpaceX documentary shows Musk as “quite self-critical, quite humble”.

It is an idea echoed by Stefan Stern, a visiting professor at the Bayes Business School at City, University of London and the author of Myths of Management. “I can’t believe that he doesn’t draw on data; it’s a leading-edge thing he’s engaged in. When you promote yourself as a sort of visionary or hero, you absolutely want to try to claim that there’s something special about your insights – they’re not a petty, banal matter of data.”

The implication is that Musk is like those schoolkids who claim not to have done a minute’s revision, then ace the exam. There is, the argument goes, something innately appealing about someone operating effortlessly on flair, instinct and inspiration: a Steve Jobs, not a Zhou Qunfei – the discreet founder of Lens Technology and the richest woman in China, who, Chamorro-Premuzic says, credits her success to “hard work and a relentless desire to learn”.

“There’s something romantic to the idea that there are mavericks who don’t need to work very hard,” adds Chamorro-Premuzic. “We say we value hard work and dedication, but, by definition, talent is more of an extraordinary gift and we celebrate that more.”

The leadership expert Eve Poole agrees. “No one wants to make it feel like hard work,” she says. “No one wants to say: ‘I slaved in front of a spreadsheet for 20 hours before I made that decision.’”

For Stern, Boris Johnson’s apparent penchant for winging it carries a similar message. “When he says: ‘We got the big calls right,’ he’s saying: ‘These small-minded people obsess about data and numbers and statistics, but with my instinct, my judgment, I – the uniquely gifted, insightful leader – got the big calls right.’ It’s not even true!”

His self-presentation as “a charismatic figure with panache who is apparently spontaneous” is particularly interesting, Stern says, given that “the other thing we know about Johnson is he’s not spontaneous, he doesn’t have good lines off the cuff”. (See that disastrous CBI Peppa Pig speech in November, recent prime minister’s questions performances or his testy, defensive responses in more probing interviews.)

Is there any foundation for the notion that gut feeling is superior to pedestrian, data-driven decision-making? The cognitive psychologist Gary Klein has spent his career researching intuition in decision-making; 35 years on, his research on how firefighters act swiftly under pressure in tough situations is still cited. “We weren’t looking for intuition,” he says. Rather, his team’s original theory was that firefighters might be rapidly evaluating two options when they decided how to tackle a fire. “They told us: ‘We don’t compare any options.’ More than that, they said: ‘We never make any decisions.’” Klein didn’t understand how firefighters could believe only one course of action was possible and land on it without making comparisons.

Further digging revealed a different picture. With 15 to 20 years of experience, Klein explains, the firefighters were classifying the situation based on fires they had seen – a process known as “pattern matching”. The second step Klein called “mental simulation”: the firefighters would visualise how a course of action would run and adjust their model accordingly. “It’s a blend of intuition and analysis,” says Klein. The process was near-instantaneous. “Most decisions were made in less than a minute.”

So, what looks like winging it can, in fact, be instinctive decision-making backed up by experience – what Poole calls “really quick heuristics in your brain … synaptic connections established through years of conditioning”. Leaders who trust that, she says, “are just fucking excellent”.

This decision-making model is common in one of the areas where people are least comfortable with the idea of winging it: healthcare. No one wants to end up in the hands of a seat-of-the-pants neurosurgeon, but Klein’s research suggests medical professionals use intuitive decision-making and gut feeling as a matter of course.

His book The Power of Intuition tells the story of an experienced neonatal intensive care unit nurse accurately diagnosing a baby with sepsis just by walking past the incubator and getting a gut feeling, when a less experienced nurse who had been conscientiously tracking all the infant’s vitals had failed to spot it. “An experienced physician sees a cluster of cues and says sepsis. We’ve heard stories of someone who was just a resident; there was a tough case and they called the attending physician. The attending physician does not even enter the room and from the door just looks at the patient and sees there’s an issue and says: ‘Ah, congestive heart failure.’”

Firefighters in New York. Gary Klein’s research suggests they use ‘a blend of intuition and analysis’ to make quick decisions. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Firefighters in New York. Gary Klein’s research suggests they use ‘a blend of intuition and analysis’ to make quick decisions. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The experiences that feed intuition can be less concrete. Poole has been researching what humans still have to offer in a world in which AI is ever-more powerful, such as what she calls “witch-style intuition” – that sense of foreboding when you enter a room or meet someone. “We all know we have had those feelings and we tend to discount them and think they’re a bit silly and weird,” she says. “But I think it’s probably coming from the collective historical unconscious, trying to keep us safe as a species.” There are, she says, two strands: “your own, desperately hard-earned gut feeling, laid down in templates of data and knowledge, then the spooky ephemera that you can pick up through ‘spidey sense’, which I think can still be really reliable.”

It can, but it isn’t always. Intuition of any kind is not infallible. Klein describes it as a “data point”: something to take into consideration, not to accept uncritically. One area in which intuition gives demonstrably poor outcomes is recruitment. As Chamorro-Premuzic explains, unstructured interview processes increase and reinforce conscious and unconscious biases about candidates. We all believe our own intuition to be superior, he says: “In an interview situation, this is a big problem, because hiring managers think they have an ability to see through candidates and to understand whether they are competent.” Companies will spend large budgets on diversity and inclusion, “then tell you they hire for ‘culture fit’ – and the main way to evaluate culture fit is whether somebody ‘feels right’ in a job interview. Even if managers are well-meaning and open-minded, they will gravitate towards candidates who are like them and they are comfortable with.”

Moreover, studies show that people tend to make up their mind in the first 60 or 90 seconds, he says. This is pattern recognition gone wrong, according to Stern. When decision-makers see someone who reminds them of themselves, they think: “Oh yeah, he’s got the right stuff. I used to be like him.”

Donald Trump springs to mind here. I read Klein a typical Trump pronouncement: “I have a gut and my gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me.” It reminds Klein of two dangerous fallacies about intuition: “One, some people think intuition is innate ability, which I don’t think it is; it’s based on experience. Two, intuition is a general skill and will apply in lots of different situations. I don’t think that’s true.” Having decent intuition in an area where you have professional experience – “like real estate”, he says, pointedly – does not mean you have a transferable skill.

Talking to people who admit to winging it reveals that, mainly, they mean the “good” kind of intuition: calling on a wealth of relevant experience and deploying it in defined circumstances. That often involves an element of performance, where spontaneity can be the secret ingredient.

Susannah, who works in publishing, says: “I love to wing it in sales presentations. When I wing it, I suddenly find a new angle; it works every time. But only, I think, because I’m winging stuff I already know deeply.” Kathy, a senior financial services strategist, says: “If it’s something I don’t know at all, I won’t wing it, but in my area of expertise I’m the queen of prep five minutes before the meeting.”

These are the good wingers, but of course the bad ones are out there – the lazy, the grandiose blaggers and the bullshitters, too often in positions of power. “There are a lot of men, particularly, who do that,” says Poole. “I think it does appeal to people who don’t feel anything any more – it’s all so boring and that’s the way they get some feelings. It gives them a massive adrenaline rush; it makes them feel very powerful and victorious.” It is not usually a successful long-term strategy, she adds, comfortingly; what Chamorro-Premuzic calls “the sense of Teflon-style immunity” betrays them eventually. “I just think you get caught out. It’s the spin of the wheel and that’s why I hate it: it’s so risky for your organisation.”

But we still admire them, buy their products, even vote for them. Why do we fall for it? It is a lack of “followership maturity”, according to Chamorro-Premuzic, and varies from culture to culture. “I grew up in South America, where if you work hard and you succeed you’re automatically a loser,” he says. “Whereas if you bullshit and deceive people, we should worship you. There are cultures that truly value self-improvement, hard work and knowledge and there are cultures that value confidence.”

A country that wants to be entertained, he says, is likely to apply low standards for leadership, preferring self-belief to caution and hard work. “Whether it’s Trump, Boris, Steve Jobs, Elon Musk – they celebrate them because they challenge the establishment. When they behave in anarchic ways, disrespecting the rules, I think they can channel the anger that people have.” The kicker is that we assume there’s some competence behind the blagging and bluster, that the emperor is fully clothed. But how do we work out if it is true: spreadsheet or gut?

There are, it seems, two types of “winging it” stories. First, there are the triumphant ones – the victories pulled, cheekily, improbably, from the jaws of defeat. Like the time a historian (who prefers to remain nameless) turned up to give a talk on one subject, only to discover her hosts were expecting, and had advertised, another. “I wrote the full thing – an hour-long show – in 10 panicked minutes,” she says. “At the end, a lady came up to congratulate me on how spontaneous my delivery was.”

Then there is the other kind of winging it story – the kind that ends in ignominy. Remember the safeguarding minister, Rachel Maclean, tying herself in factually inaccurate knots when asked about stop-and-search powers? The Australian journalist Matt Doran, who interviewed Adele without listening to her album? Or the culture secretary, Nadine Dorries, claiming Channel 4 was publicly funded, then that Channel 5 had been privatised?

There are even worse examples. As a young journalist, Sarah Dempster was unwell when she was supposed to review a Meat Loaf concert, so she wrote the piece without attending. “An hour after publication, the paper called to inform me that the gig had, in fact, been cancelled. I was sacked,” she tweeted. “The Sun wrote a piece about it. The headline: ‘MEAT OAF’.”

Why does anyone wing it, and how do they dare? As a lifelong dreary prepper, I have been wondering this since reading a profile in the New York Times of winger extraordinaire Elon Musk. “To a degree unseen in any other mogul, the entrepreneur acts on whim, fancy and the certainty that he is 100% right,” it related, detailing how Musk wings even the biggest decisions, operating on gut feeling and without a business plan, rejecting expert advice.

Genius or graft? Apple founder Steve Jobs and Zhou Qunfei, China’s richest woman. Composite: Getty/Shutterstock/Guardian Design

Genius or graft? Apple founder Steve Jobs and Zhou Qunfei, China’s richest woman. Composite: Getty/Shutterstock/Guardian DesignWhat, I wonder, is the appeal of this strategy? And is it a legitimate – indeed, more successful – way of doing business? Can Musk, the CEO of Tesla (a company with a market capitalisation of £570bn) and the founder of SpaceX (the first private company to send humans into space) really be winging it?

Some are sceptical. “Is this self-presentation or an accurate statement?” asks Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, an organisational psychologist and the author of Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? “Musk is probably way too smart to actually operate under that principle; he uses this arrogant self-presentation to his advantage. Brand Musk accounts for a big chunk of his success.” In contrast, he says, the recent Netflix SpaceX documentary shows Musk as “quite self-critical, quite humble”.

It is an idea echoed by Stefan Stern, a visiting professor at the Bayes Business School at City, University of London and the author of Myths of Management. “I can’t believe that he doesn’t draw on data; it’s a leading-edge thing he’s engaged in. When you promote yourself as a sort of visionary or hero, you absolutely want to try to claim that there’s something special about your insights – they’re not a petty, banal matter of data.”

The implication is that Musk is like those schoolkids who claim not to have done a minute’s revision, then ace the exam. There is, the argument goes, something innately appealing about someone operating effortlessly on flair, instinct and inspiration: a Steve Jobs, not a Zhou Qunfei – the discreet founder of Lens Technology and the richest woman in China, who, Chamorro-Premuzic says, credits her success to “hard work and a relentless desire to learn”.

“There’s something romantic to the idea that there are mavericks who don’t need to work very hard,” adds Chamorro-Premuzic. “We say we value hard work and dedication, but, by definition, talent is more of an extraordinary gift and we celebrate that more.”

The leadership expert Eve Poole agrees. “No one wants to make it feel like hard work,” she says. “No one wants to say: ‘I slaved in front of a spreadsheet for 20 hours before I made that decision.’”

For Stern, Boris Johnson’s apparent penchant for winging it carries a similar message. “When he says: ‘We got the big calls right,’ he’s saying: ‘These small-minded people obsess about data and numbers and statistics, but with my instinct, my judgment, I – the uniquely gifted, insightful leader – got the big calls right.’ It’s not even true!”

His self-presentation as “a charismatic figure with panache who is apparently spontaneous” is particularly interesting, Stern says, given that “the other thing we know about Johnson is he’s not spontaneous, he doesn’t have good lines off the cuff”. (See that disastrous CBI Peppa Pig speech in November, recent prime minister’s questions performances or his testy, defensive responses in more probing interviews.)

Is there any foundation for the notion that gut feeling is superior to pedestrian, data-driven decision-making? The cognitive psychologist Gary Klein has spent his career researching intuition in decision-making; 35 years on, his research on how firefighters act swiftly under pressure in tough situations is still cited. “We weren’t looking for intuition,” he says. Rather, his team’s original theory was that firefighters might be rapidly evaluating two options when they decided how to tackle a fire. “They told us: ‘We don’t compare any options.’ More than that, they said: ‘We never make any decisions.’” Klein didn’t understand how firefighters could believe only one course of action was possible and land on it without making comparisons.

Further digging revealed a different picture. With 15 to 20 years of experience, Klein explains, the firefighters were classifying the situation based on fires they had seen – a process known as “pattern matching”. The second step Klein called “mental simulation”: the firefighters would visualise how a course of action would run and adjust their model accordingly. “It’s a blend of intuition and analysis,” says Klein. The process was near-instantaneous. “Most decisions were made in less than a minute.”

So, what looks like winging it can, in fact, be instinctive decision-making backed up by experience – what Poole calls “really quick heuristics in your brain … synaptic connections established through years of conditioning”. Leaders who trust that, she says, “are just fucking excellent”.

This decision-making model is common in one of the areas where people are least comfortable with the idea of winging it: healthcare. No one wants to end up in the hands of a seat-of-the-pants neurosurgeon, but Klein’s research suggests medical professionals use intuitive decision-making and gut feeling as a matter of course.

His book The Power of Intuition tells the story of an experienced neonatal intensive care unit nurse accurately diagnosing a baby with sepsis just by walking past the incubator and getting a gut feeling, when a less experienced nurse who had been conscientiously tracking all the infant’s vitals had failed to spot it. “An experienced physician sees a cluster of cues and says sepsis. We’ve heard stories of someone who was just a resident; there was a tough case and they called the attending physician. The attending physician does not even enter the room and from the door just looks at the patient and sees there’s an issue and says: ‘Ah, congestive heart failure.’”

Firefighters in New York. Gary Klein’s research suggests they use ‘a blend of intuition and analysis’ to make quick decisions. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Firefighters in New York. Gary Klein’s research suggests they use ‘a blend of intuition and analysis’ to make quick decisions. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty ImagesThe experiences that feed intuition can be less concrete. Poole has been researching what humans still have to offer in a world in which AI is ever-more powerful, such as what she calls “witch-style intuition” – that sense of foreboding when you enter a room or meet someone. “We all know we have had those feelings and we tend to discount them and think they’re a bit silly and weird,” she says. “But I think it’s probably coming from the collective historical unconscious, trying to keep us safe as a species.” There are, she says, two strands: “your own, desperately hard-earned gut feeling, laid down in templates of data and knowledge, then the spooky ephemera that you can pick up through ‘spidey sense’, which I think can still be really reliable.”

It can, but it isn’t always. Intuition of any kind is not infallible. Klein describes it as a “data point”: something to take into consideration, not to accept uncritically. One area in which intuition gives demonstrably poor outcomes is recruitment. As Chamorro-Premuzic explains, unstructured interview processes increase and reinforce conscious and unconscious biases about candidates. We all believe our own intuition to be superior, he says: “In an interview situation, this is a big problem, because hiring managers think they have an ability to see through candidates and to understand whether they are competent.” Companies will spend large budgets on diversity and inclusion, “then tell you they hire for ‘culture fit’ – and the main way to evaluate culture fit is whether somebody ‘feels right’ in a job interview. Even if managers are well-meaning and open-minded, they will gravitate towards candidates who are like them and they are comfortable with.”

Moreover, studies show that people tend to make up their mind in the first 60 or 90 seconds, he says. This is pattern recognition gone wrong, according to Stern. When decision-makers see someone who reminds them of themselves, they think: “Oh yeah, he’s got the right stuff. I used to be like him.”

Donald Trump springs to mind here. I read Klein a typical Trump pronouncement: “I have a gut and my gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me.” It reminds Klein of two dangerous fallacies about intuition: “One, some people think intuition is innate ability, which I don’t think it is; it’s based on experience. Two, intuition is a general skill and will apply in lots of different situations. I don’t think that’s true.” Having decent intuition in an area where you have professional experience – “like real estate”, he says, pointedly – does not mean you have a transferable skill.

Talking to people who admit to winging it reveals that, mainly, they mean the “good” kind of intuition: calling on a wealth of relevant experience and deploying it in defined circumstances. That often involves an element of performance, where spontaneity can be the secret ingredient.

Susannah, who works in publishing, says: “I love to wing it in sales presentations. When I wing it, I suddenly find a new angle; it works every time. But only, I think, because I’m winging stuff I already know deeply.” Kathy, a senior financial services strategist, says: “If it’s something I don’t know at all, I won’t wing it, but in my area of expertise I’m the queen of prep five minutes before the meeting.”

These are the good wingers, but of course the bad ones are out there – the lazy, the grandiose blaggers and the bullshitters, too often in positions of power. “There are a lot of men, particularly, who do that,” says Poole. “I think it does appeal to people who don’t feel anything any more – it’s all so boring and that’s the way they get some feelings. It gives them a massive adrenaline rush; it makes them feel very powerful and victorious.” It is not usually a successful long-term strategy, she adds, comfortingly; what Chamorro-Premuzic calls “the sense of Teflon-style immunity” betrays them eventually. “I just think you get caught out. It’s the spin of the wheel and that’s why I hate it: it’s so risky for your organisation.”

But we still admire them, buy their products, even vote for them. Why do we fall for it? It is a lack of “followership maturity”, according to Chamorro-Premuzic, and varies from culture to culture. “I grew up in South America, where if you work hard and you succeed you’re automatically a loser,” he says. “Whereas if you bullshit and deceive people, we should worship you. There are cultures that truly value self-improvement, hard work and knowledge and there are cultures that value confidence.”

A country that wants to be entertained, he says, is likely to apply low standards for leadership, preferring self-belief to caution and hard work. “Whether it’s Trump, Boris, Steve Jobs, Elon Musk – they celebrate them because they challenge the establishment. When they behave in anarchic ways, disrespecting the rules, I think they can channel the anger that people have.” The kicker is that we assume there’s some competence behind the blagging and bluster, that the emperor is fully clothed. But how do we work out if it is true: spreadsheet or gut?

Monday, 6 December 2021

Looks fast, feels faster - why the speed gun is only part of the story

Data on release points and trajectory are helping to break down the mysteries of why some bowlers are harder to face than others writes Cameron Ponsonby in Cricinfo

Shubman Gill ducks a Pat Cummins bouncer during India's Test tour of Australia in 2020-21 AFP/Getty Images

South Africa's Andrew Hall is on strike against Brett Lee at the Wanderers stadium in Johannesburg. The ball is bowled and Hall tucks it into the leg side before setting off for a gentle single.

As he jogs to the other end he hears a belated cheer from the crowd. Confused, he looks around to see the big screen displaying an announcement. He has just faced the fastest ball ever to have been bowled at the Wanderers.

Still confused, Hall's eyes move from the screen to Lee and they trade a quizzical look: "There's no way that was that quick."

The next ball, Lee runs in and bowls a bouncer to Gary Kirsten that flies past his face. Lee and Hall catch each other's eye once more,

"That one was."

You see, the speed gun is the movie adaptation of your favourite book. Yes, it tells the story. But it doesn't tell the full one.

****

"A lot of what makes Test players special happens before the ball comes out of a bowler's hand."

Those are the words of England analyst Nathan Leamon, speaking on Jarrod Kimber's Red Inker podcast. As a starting point, it shines a light on one of the limitations of the speed gun. It only tells us how fast a ball is at the point of release and tells us nothing about what has happened before or what happens after.

And what happens before is crucial. It is very easy to think of facing fast bowling as primarily a reactive skill. In fact, read any article on quick bowling and it will invariably say you only have 0.4 seconds to react to a 90mph delivery.

But what does that mean? No one can compute information in 0.4 seconds. It's beyond our realm of thinking in the same way that looking out of an aeroplane window doesn't give you vertigo because you're simply too high up for your brain to process it.

However, the reason it's possible is because, whilst you may only have 0.4 seconds to react, you have a lot longer than that to plan. And the best in the world plan exceptionally well.

Hall describes a training method that South Africa would use in order to be able to associate a bowler's release point with length. After a ball was bowled, they'd walk down the wicket and place a cone or mark a spot with their bat where they believed the ball had landed. The coach would confirm it or correct what the player thought.

The idea is in essence basic trigonometry. Over time, you learn to associate that if a bowler releases the ball with his arm at 12 o'clock, the delivery would be full. If he releases the ball at 1 o'clock, it would be short. It's a process designed to consciously train the subconscious, and Jacques Kallis was the best at it.

"Whether he played and missed," Hall says, "or left it, or ducked out the way, he'd be able to come down the track and isolate a rough area of where that ball had landed. And the reason he was so good at it is he became really sharp at picking up length and he made some bowlers look slower because of that. Because as they let go of the ball, he knew within a couple of inches where it was going to land."

Jasprit Bumrah roars after having Joe Root caught in the slips AFP/Getty Images

Jasprit Bumrah roars after having Joe Root caught in the slips AFP/Getty Images

There are a number of pre-delivery cues that Hall, as an international player, would be looking out for. Some were obvious tells, such as a bowler running in that bit harder before bowling a bouncer; others more subtle, like a bowler's head falling away in their action so they were able to push the ball into the batter and bowl an inswinger.

These cues weren't restricted to fast bowlers either. When talking about how to face Muthiah Muralidaran, Hall explains that one of the cues the South Africans would look out for was where his right elbow would be pointing as he entered his delivery stride. If it was pointing out at 90 degrees with his hand by his ear lobe, that was the sign that Muralitharan was going to bowl his off-spinner. If his elbow was pointing down towards the batter, it was probably a doosra coming up.

"You still wouldn't be able to play it half the time," Hall adds, "but you had an idea."

And some bowlers give you more of these cues than others, meaning a bowler at 87mph may feel quicker than one at 90mph if they give the batter fewer clues in their action.

Mark Ramprakash spoke of this when comparing his experience of facing Lee and Jason Gillespie in the 2001 Ashes. Lee was the faster bowler of the two, but his textbook action, with the ball always in sight, meant that Ramprakash felt he could consistently time his pre-delivery movement. But when he faced Gillespie, despite his being slower on the speed gun, it felt quicker. And this was because Gillespie would appear almost to release the ball before he'd really landed on the ground, throwing off Ramprakash's timings. When facing Lee, Ramprakash was planning. But when he was facing Gillespie, he was reacting.

In simple terms, there's a correlation between a bowler being "different" and the feeling that they are faster than they actually are. Batters are brought up on a diet of right-arm-over bowling that is released from nigh-on the same area, ball after ball after ball. Remove that familiarity, and the feeling of speed goes up.

In the Caribbean in 2019, TV showed Jasprit Bumrah's release point was half a metre closer to the batter than Kemar Roach's. This gave Bumrah the effect of bowling 3.7mph faster than the speed gun was showing

"Take Lasith Malinga," Hall says. "If you've not faced him before, you're literally going 'what am I supposed to watch?' But you soon get told, when he gets into his action, to watch the umpire's chest and neck. If you're watching his arm, you're struggling. And that's why in the beginning he'd clean people up and they'd say 'ah, he's quick'. He's not that quick. You just couldn't follow the ball."

****

Another quirk of how we consider pace is that by measuring the speed at which a ball is released, we're not actually measuring how long it takes to reach the batter. And there's a difference.

For instance, if you set up a bowling machine at 85mph and deliver three balls in a row, one of which is a full toss, the second a good length delivery and the third a bouncer, each of the three balls will reach the other end in a different amount of time because when the ball hits the pitch, it slows down. And the steeper that impact is, the more it will slow. So counterintuitively, the bouncer, cricket's scariest delivery, is actually the slowest of the three, whereas the full toss, cricket's worst delivery, is the fastest.

But what we don't know is how different bowlers compare to each other in terms of how much pace they lose off the wicket. The information is out there, but it's just not readily available. Angus Reid from VirtualEye - the company that provides ball-tracking data for Test matches in Australia - recalls how, during Naseem Shah's Test debut for Pakistan, they did a piece for broadcast comparing how he and Australia's Pat Cummins were releasing the ball at very similar speeds, but Shah was reaching the batter faster due to a combination of his height, ball trajectory and "skiddy" nature.

Steven Smith was pinned by a Jofra Archer bouncer at Lord's in 2019 Getty Images

Steven Smith was pinned by a Jofra Archer bouncer at Lord's in 2019 Getty Images

And we know from player anecdotes that these things matter. Hall explains how bowlers will sometimes bowl their bouncer with a cross-seam in the hope that the ball lands on the lacquer and loses less pace when it pitches. It is the same notion that Joe Root expressed earlier this year when he said India's spinner Axar Patel was beating England for pace in the pink-ball Test at Ahmedabad, because the skid off the lacquer gave the feeling that the ball was "gathering pace" off the wicket.

Conversely, many bowlers are said to bowl a "heavy ball", whereby batters feel that the ball is "hitting the bat harder" than expected. One such bowler was New Zealand bowler Iain O'Brien, who believes this was a consequence of the ball kicking up off the pitch and striking the blade higher than anticipated, due to more backspin being imparted upon release. Such was the backspin that Andrew Flintoff imparted on the ball, in the lead up to the 2005 Ashes he was accused of chucking as his wrist would snap so dramatically at the point of delivery.

This is one of the difficulties of trying to express the feeling of speed to a wider audience. For the spectator, it's merely a number because we have no other frame of reference. But for the batter, it's an experience. A moment in time that is almost over before it's begun.

One former international cricketer laughed when asked whether he would check the speed gun after facing a delivery. "Why would I need the speed gun to tell me if a ball was fast? I was the one who just faced it."

****

The final piece of the puzzle concerns the ball's release point.

When India were touring the Caribbean in 2019, TV showed an overlay of Jasprit Bumrah's release point compared to Kemar Roach's, demonstrating that Bumrah was bowling the ball half a metre closer to the batter than Roach. Some quick maths showed that this gave Bumrah the effect of bowling 3.7mph faster than the speed gun was showing. Cricket has long been played on a pitch that is 22 yards. Bumrah plays on one that is 21.5.

Admittedly, this advantage was spotted because Bumrah is on the extreme, gazillion-jointed end of the scale, enabling him to bowl closer than anyone else in a way that other bowlers can't. But given we pay attention to how wide on the crease a bowler will bowl and also how high a bowler's release point is, surely we should know how close a bowler is bowling to the batter, given it is the single easiest way of apparently increasing pace.

This effect is measured in baseball. In fact, everything is. While cricket shrugs its shoulders and says "I guess we'll never know, folks" for a myriad of data-points, every intangible detail in baseball is known and measured.

How close a pitcher releases the ball to a batter is known as "Extension" and translates to what's known as "Perceived Velocity". Famed pitching coach Tom House believes that, if you can throw the ball one foot closer to the batter, then it equals an extra 3mph for the person at the other end. Tyler Glasnow and Luis Castillo are two pitchers who both throw their fast-ball at 97mph. Glasnow's extension is one of the best in the league and Castillo's is one of the worst. As a result, Glasnow feels like he is throwing at 99mph and Castillo feels like he is throwing at 95mph.Spin rates, which could resolve cricket's heavy-ball phenomenon, are a hugely important measurement in baseball - so much so that they can now be taken into consideration in the selection process.

Even the ultimate intangible, the impact an action has on a batter before the ball has been released, is beginning to be quantified by a biomechanics company known as ProPlayAI, who have started tracking what they call a "deception metric", which measures the amount of time a batter has to see the ball in a pitcher's hand before release.

Mitchell Johnson was ferociously quick during the 2013-14 Ashes Getty Images

Mitchell Johnson was ferociously quick during the 2013-14 Ashes Getty Images

The culmination of all these factors comes in the form of a pitcher named Yusemeiro Petit, described by baseball writer Ben Lindbergh as "the poster boy for the power of deception".

Petit's average fast-ball is 87mph. A whole 7mph slower than the rest of the league. He is 37 years old and over 500 games into his career. And he has made it this far, not by being a force of nature but by representing the mystery of it. He is one of those alien fishes at the bottom of the ocean that has lived forever and we don't know why.

In the 2005 edition of the Prospect Handbook, Baseball America, which is the sport's annual guide on the young players to look out for, Petit was described as leaving "batters and scouts scratching their heads ... Nothing about it [his fast-ball] appears to be exceptional - except how hitters never seem to get a good swing against it."

Fast forward to the present day and the reasons for Petit's success are beginning to be decoded. Simply put, Lindbergh describes him as a "hider and a strider". Throwing the ball far closer to home plate than would be expected and giving the batter little to no sight of the ball in the process. The result of which is a pitcher who is far quicker than the speed gun would lead you to believe.

****

All of this isn't to say that the speed gun is useless. It isn't. But it represents different things to different people. As a broadcasting tool, it's an excellent way of telling a story in a bite-size chunk. And for a bowler, it represents the result of their process. Get everything right and watch that number go up.

For batters, however, it represents part of the process that leads to their result. Yes, the speed of a ball upon release is important. But we know that there are other factors at play, because the players at the receiving end of it say so. And ultimately, who would you rather face? A bowler that a machine says is fast? Or one that a human says feels even faster?

South Africa's Andrew Hall is on strike against Brett Lee at the Wanderers stadium in Johannesburg. The ball is bowled and Hall tucks it into the leg side before setting off for a gentle single.

As he jogs to the other end he hears a belated cheer from the crowd. Confused, he looks around to see the big screen displaying an announcement. He has just faced the fastest ball ever to have been bowled at the Wanderers.

Still confused, Hall's eyes move from the screen to Lee and they trade a quizzical look: "There's no way that was that quick."

The next ball, Lee runs in and bowls a bouncer to Gary Kirsten that flies past his face. Lee and Hall catch each other's eye once more,

"That one was."

You see, the speed gun is the movie adaptation of your favourite book. Yes, it tells the story. But it doesn't tell the full one.

****

"A lot of what makes Test players special happens before the ball comes out of a bowler's hand."

Those are the words of England analyst Nathan Leamon, speaking on Jarrod Kimber's Red Inker podcast. As a starting point, it shines a light on one of the limitations of the speed gun. It only tells us how fast a ball is at the point of release and tells us nothing about what has happened before or what happens after.

And what happens before is crucial. It is very easy to think of facing fast bowling as primarily a reactive skill. In fact, read any article on quick bowling and it will invariably say you only have 0.4 seconds to react to a 90mph delivery.

But what does that mean? No one can compute information in 0.4 seconds. It's beyond our realm of thinking in the same way that looking out of an aeroplane window doesn't give you vertigo because you're simply too high up for your brain to process it.

However, the reason it's possible is because, whilst you may only have 0.4 seconds to react, you have a lot longer than that to plan. And the best in the world plan exceptionally well.

Hall describes a training method that South Africa would use in order to be able to associate a bowler's release point with length. After a ball was bowled, they'd walk down the wicket and place a cone or mark a spot with their bat where they believed the ball had landed. The coach would confirm it or correct what the player thought.

The idea is in essence basic trigonometry. Over time, you learn to associate that if a bowler releases the ball with his arm at 12 o'clock, the delivery would be full. If he releases the ball at 1 o'clock, it would be short. It's a process designed to consciously train the subconscious, and Jacques Kallis was the best at it.

"Whether he played and missed," Hall says, "or left it, or ducked out the way, he'd be able to come down the track and isolate a rough area of where that ball had landed. And the reason he was so good at it is he became really sharp at picking up length and he made some bowlers look slower because of that. Because as they let go of the ball, he knew within a couple of inches where it was going to land."

Jasprit Bumrah roars after having Joe Root caught in the slips AFP/Getty Images

Jasprit Bumrah roars after having Joe Root caught in the slips AFP/Getty ImagesThere are a number of pre-delivery cues that Hall, as an international player, would be looking out for. Some were obvious tells, such as a bowler running in that bit harder before bowling a bouncer; others more subtle, like a bowler's head falling away in their action so they were able to push the ball into the batter and bowl an inswinger.

These cues weren't restricted to fast bowlers either. When talking about how to face Muthiah Muralidaran, Hall explains that one of the cues the South Africans would look out for was where his right elbow would be pointing as he entered his delivery stride. If it was pointing out at 90 degrees with his hand by his ear lobe, that was the sign that Muralitharan was going to bowl his off-spinner. If his elbow was pointing down towards the batter, it was probably a doosra coming up.

"You still wouldn't be able to play it half the time," Hall adds, "but you had an idea."

And some bowlers give you more of these cues than others, meaning a bowler at 87mph may feel quicker than one at 90mph if they give the batter fewer clues in their action.

Mark Ramprakash spoke of this when comparing his experience of facing Lee and Jason Gillespie in the 2001 Ashes. Lee was the faster bowler of the two, but his textbook action, with the ball always in sight, meant that Ramprakash felt he could consistently time his pre-delivery movement. But when he faced Gillespie, despite his being slower on the speed gun, it felt quicker. And this was because Gillespie would appear almost to release the ball before he'd really landed on the ground, throwing off Ramprakash's timings. When facing Lee, Ramprakash was planning. But when he was facing Gillespie, he was reacting.

In simple terms, there's a correlation between a bowler being "different" and the feeling that they are faster than they actually are. Batters are brought up on a diet of right-arm-over bowling that is released from nigh-on the same area, ball after ball after ball. Remove that familiarity, and the feeling of speed goes up.

In the Caribbean in 2019, TV showed Jasprit Bumrah's release point was half a metre closer to the batter than Kemar Roach's. This gave Bumrah the effect of bowling 3.7mph faster than the speed gun was showing

"Take Lasith Malinga," Hall says. "If you've not faced him before, you're literally going 'what am I supposed to watch?' But you soon get told, when he gets into his action, to watch the umpire's chest and neck. If you're watching his arm, you're struggling. And that's why in the beginning he'd clean people up and they'd say 'ah, he's quick'. He's not that quick. You just couldn't follow the ball."

****

Another quirk of how we consider pace is that by measuring the speed at which a ball is released, we're not actually measuring how long it takes to reach the batter. And there's a difference.

For instance, if you set up a bowling machine at 85mph and deliver three balls in a row, one of which is a full toss, the second a good length delivery and the third a bouncer, each of the three balls will reach the other end in a different amount of time because when the ball hits the pitch, it slows down. And the steeper that impact is, the more it will slow. So counterintuitively, the bouncer, cricket's scariest delivery, is actually the slowest of the three, whereas the full toss, cricket's worst delivery, is the fastest.

But what we don't know is how different bowlers compare to each other in terms of how much pace they lose off the wicket. The information is out there, but it's just not readily available. Angus Reid from VirtualEye - the company that provides ball-tracking data for Test matches in Australia - recalls how, during Naseem Shah's Test debut for Pakistan, they did a piece for broadcast comparing how he and Australia's Pat Cummins were releasing the ball at very similar speeds, but Shah was reaching the batter faster due to a combination of his height, ball trajectory and "skiddy" nature.

Steven Smith was pinned by a Jofra Archer bouncer at Lord's in 2019 Getty Images

Steven Smith was pinned by a Jofra Archer bouncer at Lord's in 2019 Getty ImagesAnd we know from player anecdotes that these things matter. Hall explains how bowlers will sometimes bowl their bouncer with a cross-seam in the hope that the ball lands on the lacquer and loses less pace when it pitches. It is the same notion that Joe Root expressed earlier this year when he said India's spinner Axar Patel was beating England for pace in the pink-ball Test at Ahmedabad, because the skid off the lacquer gave the feeling that the ball was "gathering pace" off the wicket.

Conversely, many bowlers are said to bowl a "heavy ball", whereby batters feel that the ball is "hitting the bat harder" than expected. One such bowler was New Zealand bowler Iain O'Brien, who believes this was a consequence of the ball kicking up off the pitch and striking the blade higher than anticipated, due to more backspin being imparted upon release. Such was the backspin that Andrew Flintoff imparted on the ball, in the lead up to the 2005 Ashes he was accused of chucking as his wrist would snap so dramatically at the point of delivery.

This is one of the difficulties of trying to express the feeling of speed to a wider audience. For the spectator, it's merely a number because we have no other frame of reference. But for the batter, it's an experience. A moment in time that is almost over before it's begun.

One former international cricketer laughed when asked whether he would check the speed gun after facing a delivery. "Why would I need the speed gun to tell me if a ball was fast? I was the one who just faced it."

****

The final piece of the puzzle concerns the ball's release point.

When India were touring the Caribbean in 2019, TV showed an overlay of Jasprit Bumrah's release point compared to Kemar Roach's, demonstrating that Bumrah was bowling the ball half a metre closer to the batter than Roach. Some quick maths showed that this gave Bumrah the effect of bowling 3.7mph faster than the speed gun was showing. Cricket has long been played on a pitch that is 22 yards. Bumrah plays on one that is 21.5.

Admittedly, this advantage was spotted because Bumrah is on the extreme, gazillion-jointed end of the scale, enabling him to bowl closer than anyone else in a way that other bowlers can't. But given we pay attention to how wide on the crease a bowler will bowl and also how high a bowler's release point is, surely we should know how close a bowler is bowling to the batter, given it is the single easiest way of apparently increasing pace.

This effect is measured in baseball. In fact, everything is. While cricket shrugs its shoulders and says "I guess we'll never know, folks" for a myriad of data-points, every intangible detail in baseball is known and measured.

How close a pitcher releases the ball to a batter is known as "Extension" and translates to what's known as "Perceived Velocity". Famed pitching coach Tom House believes that, if you can throw the ball one foot closer to the batter, then it equals an extra 3mph for the person at the other end. Tyler Glasnow and Luis Castillo are two pitchers who both throw their fast-ball at 97mph. Glasnow's extension is one of the best in the league and Castillo's is one of the worst. As a result, Glasnow feels like he is throwing at 99mph and Castillo feels like he is throwing at 95mph.Spin rates, which could resolve cricket's heavy-ball phenomenon, are a hugely important measurement in baseball - so much so that they can now be taken into consideration in the selection process.

Even the ultimate intangible, the impact an action has on a batter before the ball has been released, is beginning to be quantified by a biomechanics company known as ProPlayAI, who have started tracking what they call a "deception metric", which measures the amount of time a batter has to see the ball in a pitcher's hand before release.

Mitchell Johnson was ferociously quick during the 2013-14 Ashes Getty Images

Mitchell Johnson was ferociously quick during the 2013-14 Ashes Getty ImagesThe culmination of all these factors comes in the form of a pitcher named Yusemeiro Petit, described by baseball writer Ben Lindbergh as "the poster boy for the power of deception".

Petit's average fast-ball is 87mph. A whole 7mph slower than the rest of the league. He is 37 years old and over 500 games into his career. And he has made it this far, not by being a force of nature but by representing the mystery of it. He is one of those alien fishes at the bottom of the ocean that has lived forever and we don't know why.

In the 2005 edition of the Prospect Handbook, Baseball America, which is the sport's annual guide on the young players to look out for, Petit was described as leaving "batters and scouts scratching their heads ... Nothing about it [his fast-ball] appears to be exceptional - except how hitters never seem to get a good swing against it."

Fast forward to the present day and the reasons for Petit's success are beginning to be decoded. Simply put, Lindbergh describes him as a "hider and a strider". Throwing the ball far closer to home plate than would be expected and giving the batter little to no sight of the ball in the process. The result of which is a pitcher who is far quicker than the speed gun would lead you to believe.

****

All of this isn't to say that the speed gun is useless. It isn't. But it represents different things to different people. As a broadcasting tool, it's an excellent way of telling a story in a bite-size chunk. And for a bowler, it represents the result of their process. Get everything right and watch that number go up.

For batters, however, it represents part of the process that leads to their result. Yes, the speed of a ball upon release is important. But we know that there are other factors at play, because the players at the receiving end of it say so. And ultimately, who would you rather face? A bowler that a machine says is fast? Or one that a human says feels even faster?

Monday, 26 November 2018

The difficulty in managing things that cannot easily be measured

Andrew Hill in The FT

If there were a tournament for Peter Drucker’s best-known dictum then “what gets measured gets managed” would make it to the finals, even though nobody seems able to pin the saying directly to the Viennese-born management thinker. Repeated misattribution has gilded the truism and propelled it into the Management Maxim Hall of Fame.

En route, unfortunately, the assumption has taken root that everything can be measured. Worse, anything that does not submit to mathematical evaluation need not be managed, or is simply unmanageable.

This is the most prominent example of a widespread phenomenon: the tendency to pay more attention to hard facts, targets, outcomes and initiatives than to soft factors that are equally, or sometimes more, important.

Big data is hard. Culture is soft. Financial goals are hard. Non-financial targets are soft. Gender quotas are hard. Workplace inclusivity is soft. “Stem” subjects are hard. Humanities are soft. (Drucker himself described management as a liberal art.) Machines are hard — very hard. Humans are all too soft.

The Harvard Business Review tries to reconcile the hard-soft tension annually in its ranking of the “best-performing CEOs in the world”, measured over their whole tenure. Jeff Bezos wins every time. Except he doesn’t, because in 2015, the publication changed its methodology and added soft environmental, social and governance factors to its hard financial assessment, knocking Amazon’s founder from first to 87th. Mr Bezos has crept back to 68th in the latest ranking, topped by Pablo Isla, chief executive of Spanish retail group Inditex with its (soft) family values. I bet, though, that most investors would allocate capital on the hard measures of Mr Bezos’s and Mr Isla’s success.

The dominance of hard over soft is not uniform, though, and in a few areas it is receding. Would-be leaders aiming for MBAs have for years set equal, even greater, store on the value of the difficult-to-measure human networks they build during their studies. The hard MBA qualification itself has started to crumble, while employers increasingly stress development of executives’ soft skills.

Elsewhere, companies have finally begun to realise that feedback (soft) trumps forced ranking and even bonuses (both hard) when it comes to appraising and motivating staff. Governance codes now place emphasis on long-term success, healthy cultures and corporate purpose, offsetting boards’ longstanding deference to pure shareholder value.

Many of these pairs should coexist, of course. Too frequently, though, when a balance of two approaches would be best, the hard solution wins out as soon as pressure is applied.

In the classic tussle between long-term sustainability and short-term returns, too many directors and executives still obsess about hitting close-range targets. Purpose makes way for profit. The demand to compete overcomes any impulse to reap the benefits of collaboration.

Even if Drucker did not utter the “what gets measured” axiom, he had plenty to say about measurement. In 1955, he wrote in The Practice of Management how more sophisticated ways of gauging performance would enable managers and workers to direct their own work. But he also warned that if this ability were used to impose control from above, “the new technology [would] inflict incalculable harm by demoralising management and by seriously lowering the effectiveness of managers”.

Persuading executives to take greater account of soft factors requires a concerted effort. One approach is to play to their utilitarian preference for hard facts and try to measure the unmeasurable. The mania for measurement has extended beyond the production output and profit margins that could be assessed in the 1950s. Start-ups and consultancies frequently pitch to me with new ways of quantifying corporate culture, for instance.

Putting a number on the nebulous is one way to give soft achievements a hard edge. Reminding directors of the hard landing that awaits those who ignore, condone or contribute to rotten cultures is another.

At the same time, managers need to comprehend elements that cannot yet be recorded in 0s and 1s: the strength of team relationships, the importance of empathy, the value of intuition. Ingenious machines may one day put all the mysteries of human behaviour into a spreadsheet. I doubt it, though. This week’s Drucker Forum, in honour of the writer, will explore “the human dimension” of management. At least some of that dimension will always be difficult for chief executives to collect, crunch and codify on their digital dashboards. As a result, they must resolve to try harder to manage the things they will never easily measure.

If there were a tournament for Peter Drucker’s best-known dictum then “what gets measured gets managed” would make it to the finals, even though nobody seems able to pin the saying directly to the Viennese-born management thinker. Repeated misattribution has gilded the truism and propelled it into the Management Maxim Hall of Fame.

En route, unfortunately, the assumption has taken root that everything can be measured. Worse, anything that does not submit to mathematical evaluation need not be managed, or is simply unmanageable.

This is the most prominent example of a widespread phenomenon: the tendency to pay more attention to hard facts, targets, outcomes and initiatives than to soft factors that are equally, or sometimes more, important.

Big data is hard. Culture is soft. Financial goals are hard. Non-financial targets are soft. Gender quotas are hard. Workplace inclusivity is soft. “Stem” subjects are hard. Humanities are soft. (Drucker himself described management as a liberal art.) Machines are hard — very hard. Humans are all too soft.

The Harvard Business Review tries to reconcile the hard-soft tension annually in its ranking of the “best-performing CEOs in the world”, measured over their whole tenure. Jeff Bezos wins every time. Except he doesn’t, because in 2015, the publication changed its methodology and added soft environmental, social and governance factors to its hard financial assessment, knocking Amazon’s founder from first to 87th. Mr Bezos has crept back to 68th in the latest ranking, topped by Pablo Isla, chief executive of Spanish retail group Inditex with its (soft) family values. I bet, though, that most investors would allocate capital on the hard measures of Mr Bezos’s and Mr Isla’s success.

The dominance of hard over soft is not uniform, though, and in a few areas it is receding. Would-be leaders aiming for MBAs have for years set equal, even greater, store on the value of the difficult-to-measure human networks they build during their studies. The hard MBA qualification itself has started to crumble, while employers increasingly stress development of executives’ soft skills.

Elsewhere, companies have finally begun to realise that feedback (soft) trumps forced ranking and even bonuses (both hard) when it comes to appraising and motivating staff. Governance codes now place emphasis on long-term success, healthy cultures and corporate purpose, offsetting boards’ longstanding deference to pure shareholder value.

Many of these pairs should coexist, of course. Too frequently, though, when a balance of two approaches would be best, the hard solution wins out as soon as pressure is applied.

In the classic tussle between long-term sustainability and short-term returns, too many directors and executives still obsess about hitting close-range targets. Purpose makes way for profit. The demand to compete overcomes any impulse to reap the benefits of collaboration.

Even if Drucker did not utter the “what gets measured” axiom, he had plenty to say about measurement. In 1955, he wrote in The Practice of Management how more sophisticated ways of gauging performance would enable managers and workers to direct their own work. But he also warned that if this ability were used to impose control from above, “the new technology [would] inflict incalculable harm by demoralising management and by seriously lowering the effectiveness of managers”.

Persuading executives to take greater account of soft factors requires a concerted effort. One approach is to play to their utilitarian preference for hard facts and try to measure the unmeasurable. The mania for measurement has extended beyond the production output and profit margins that could be assessed in the 1950s. Start-ups and consultancies frequently pitch to me with new ways of quantifying corporate culture, for instance.

Putting a number on the nebulous is one way to give soft achievements a hard edge. Reminding directors of the hard landing that awaits those who ignore, condone or contribute to rotten cultures is another.

At the same time, managers need to comprehend elements that cannot yet be recorded in 0s and 1s: the strength of team relationships, the importance of empathy, the value of intuition. Ingenious machines may one day put all the mysteries of human behaviour into a spreadsheet. I doubt it, though. This week’s Drucker Forum, in honour of the writer, will explore “the human dimension” of management. At least some of that dimension will always be difficult for chief executives to collect, crunch and codify on their digital dashboards. As a result, they must resolve to try harder to manage the things they will never easily measure.

Wednesday, 21 November 2012

The edifice of marriage is always worth repairing

Wedded bliss doesn't exist - but a deeper passion does happen.

The Queen and Prince Philip were married on November 20, 1947 Photo: PA

There are innumerable reasons to admire our monarch, but 65 years of conjugal accord comes close to topping the list. Note that I do not use the trite expression “wedded bliss”. I have yet to meet any long-hitched couple who’ve been skipping around in a permanent state of ecstasy for multiple decades. Most lengthy relationships are only one part romance to two parts endurance test. Many people claim they’re never bored in their marriage, when what they really mean is they are yoked to someone who takes eccentricity and intransigence to new heights of bloody-mindedness.

Even when you do have the great good fortune to be married to someone interesting, they can’t be riveting over the cornflakes every day for 50 years. My own husband is a walking compendium of intriguing facts, but I still want to sink an axe into his skull every time he mentions local planning regs. It’s no wonder that when the late Anne Bancroft was asked the secret of her 41-year marriage to Mel Brooks, she growled, “Just working hard.” I bet the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh would concur with that: not only have they had to head up “the Firm” for 65 gruelling years, they have also had to support three of their children through equally testing matrimonial disappointments.

I couldn’t help but imagine the Duke sending a salute across the ether to retired Navy officer Nick Crews, whose excoriating email to his divorced children bemoaned their “copulation-driven” splits. I don’t imagine Crews is any more prudish than most naval men of his ilk – more likely he believes it’s weedy to abandon a decent spouse for the sake of erotic diversion. In the not-so-distant past, couples worked their way through such indiscretions in the same way they would tackle financial or medical problems: there may have been damage to the render and chimney pots, but nothing that troubled the whole stately edifice. But we Generation X types are too recreation-minded to bother with tedious repairs; it’s no wonder we find the long-entwined so mesmerising, yet baffling.

I have had some fun imagining what Crews would say about the female banker who reportedly divorced her husband because of his “boring attitude” to sex. I imagine it would be something along the lines of, “Brace up woman! My generation didn’t get to where we are today without enduring a spot of sexual tedium.” As any marital veteran will tell you, you can cherish a passion for your spouse that’s far deeper than mere sexual flames. However, you may have to stick in your marriage for a fair few decades to appreciate that wisdom.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)