'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Saturday, 10 December 2022

Monday, 25 July 2022

Strict inflation targets for central banks have caused economic harm

Edward Chancellor in The FT

A great experiment in monetary policy is drawing to a close. Last week, the European Central Bank announced its largest rate hike in two decades, taking its benchmark rate back to just zero per cent. Never before, over the course of some 5,000 years of lending, have interest rates sunk so low. Those who rue the consequences of easy money are quick to blame central bankers. But the problem originates with the strict inflation mandates they are required to follow.

In 1990, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand became the first central bank to adopt a formal target. In 1997 a newly independent Bank of England was also given a target, as was the ECB when it opened for business a year later. After the global financial crisis, both the Federal Reserve and Bank of Japan jumped on board. What BOJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda called the “global standard” — an inflation target in the range of 2 per cent — performed several functions: providing central banks with a clearly defined benchmark, anchoring inflation expectations and relieving politicians of responsibility for monetary policy.

The trouble is that whenever an institution is guided by a specific target, critical judgment tends to be suspended. As the late political scientist Donald Campbell wrote, “the more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making”, the higher the risk it will distort and corrupt the processes involved. This problem is well known in monetary policymaking circles. In the 1970s Charles Goodhart of the London School of Economics noted that whenever the BoE targeted a specific measure of the money supply, this measure’s earlier relationship to inflation broke down. Goodhart’s Law states that any measure used for control is unreliable.

Inflation-targeting runs true to form. Thanks in large measure to globalisation and technological advances, inflationary pressures abated in the 1990s, allowing central bankers to lower interest rates. After the dotcom bust at the turn of the century, fears of deflation induced the Federal Reserve to set its Fed funds rate at a postwar low of 1 per cent. A global credit boom followed. The ensuing bust unleashed even stronger deflationary pressures. The Fed proceeded to cut its policy rate to zero. In Europe and Japan, rates turned negative for the first time in history.

Throughout the following decade, central bankers justified their actions by reference to their inflation targets. Yet these targets produced a number of corruptions and distortions. Ultra-low interest rates pushed the US stock market to near record valuations and provided the impetus for the “everything bubble” in a wide variety of assets ranging from cryptocurrencies to vintage cars. Forced to “chase yield”, investors assumed more risk. The fall in long-term rates hurt savings and triggered a massive increase in pension deficits. Easy money kept zombie businesses afloat and swamped Silicon Valley with blind capital. Companies and governments availed themselves of cheap credit to take on more debt.

Most economists assume that interest rates simply reflect what’s going on in what they call the “real economy”. But, as Claudio Borio at the Bank for International Settlements argues, the cost of borrowing both reflects and, in turn, influences economic activity. In Borio’s view, the era of ultra-low interest rates pushed the global economy far from equilibrium. As he puts it, low rates begot even lower rates.

During the pandemic central bankers were still striving to meet their inflation targets when they lowered interest rates and printed trillions of dollars, much of which was used by their governments to meet the extraordinary costs of lockdowns. Now, inflation is back and central banks are scrambling to regain control without crashing the economy or inducing yet another financial crisis. The fact that policy rates trail far below inflation, on both sides of the Atlantic, suggests that monetary policymakers are no longer blindly following their inflation targets to the exclusion of all other considerations.

This is welcome. But elected politicians cannot continue to shirk responsibility. They need to reconsider central banks’ mandates, taking into account the impact of monetary policy not just on near-term inflation, but on asset valuations (especially real estate), leverage, financial stability and investment. The experiment with zero and negative rates has done considerable harm. It must never be repeated. As Mervyn King, the former BoE governor, says: “We have not targeted those things which we ought to have targeted and we have targeted those things which we ought not to have targeted, and there is no health in the economy.”

Saturday, 5 June 2021

Monday, 31 May 2021

Sunday, 14 March 2021

Debt levels are not an issue

Tearing at the Tory party’s fabric is the thought of spiralling government debt. The subject triggers a cold sweat in some of the most emotionally resilient Conservative backbench MPs, such is the distress it generates.

Much as the German centre-right parties have spent the past 90 years fearing a return of hyperinflation, their UK counterparts worry about paying the national mortgage bill, and the possibility it will one day engulf and sink the ship of state.

Since the budget, there is a sense that the costs of the pandemic, of levelling up, of going green and of social care – to name just four candidates for extra spending – are scarily high.

Plenty of economists say these costs can be managed with higher borrowing. Even the experts who warned against rising debts back in 2009 have changed their minds. The International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development say that after 30 years of falling interest rates, this is the moment to stick extra spending on a buy now, pay later tab.

Yet, gnawing away at the Tory soul is the prospect of an increase in interest rates by a fragile Bank of England, an institution that owns more than a third of UK government debt. This week, Threadneedle Street’s monetary policy committee meets to discuss the state of the economy and whether it needs to adjust its current 0.1% base rate.

Last year the committee was concerned that the economic situation was so bad it might need to lower interest rates even further, pushing them into negative territory. In recent weeks, though, the success of the vaccine programme, some additional spending by Rishi Sunak in his spring budget and Joe Biden’s monster stimulus package – which has made its way unscathed through the US Congress – have turned a few heads.

Now there are warnings of a rebound in growth so strong that it will force central banks to calm things down with the much-dreaded increase in interest rates.

At Thursday’s meeting, Andrew Bailey will mark a year as governor, and will be forgiven for wanting to draw breath. Within weeks of the handover from Mark Carney, he was plunged into the pandemic and – like his counterpart in the Treasury, Sunak – forced to plot a way through the crisis.

Bailey should set aside his in-tray and do the nation a favour by making explicit what, in a post-pandemic world, the Bank’s mandate means. And what he should say is neither outlandish nor controversial.

It should not differ wildly from what Jerome Powell, the head of the US central bank, said last week. Bailey should explain that the Bank’s focus is on generating a path for growth that has momentum and is sustainable. Only when the Bank can verify that jobs are being created – and, more importantly, that pay rises of at least 4% a year are being awarded – will it begin to consider tightening monetary policy.

This means interest rates cannot increase until the government has two things working in its favour. First, that there are enough jobs and pay increases to generate the level of tax receipts that can pay for higher debt bills. Second, that there is a level of growth which means the debt-to-GDP ratio, expected to hit about 110% during this parliament, starts coming down, even as the government spends more.

If Bailey says this like he means it, those who worry about rising interest rates can switch to worrying about something else, such as the climate emergency, Britain’s spectacular loss of biodiversity and rising levels of child poverty.

Bailey’s record over his first year in charge does not augur well. While he was sure-footed at the outset of the pandemic, dusting off the 2008 crisis playbook and printing a huge sum of money to restore confidence, things soon started to go awry.

He has flip-flopped from optimist to pessimist on the economy while throwing incendiary devices on the fears of those who worry about debt. In an interview last June, for example, he claimed the bond markets brought Britain close to insolvency when the bank launched its first pandemic rescue operation. It was an exaggeration that matched the hyperbole of his recent support for the idea that consumers are ready to “binge” once lockdown eases.

If the past 10 years has taught us anything, it is that the Bank has consistently done too little to help the economy and not too much. Bailey could ask Sunak to overhaul the MPC remit, increasing the inflation target from the current 2% to 3% or 4%, or bolting on a growth target that would force the Bank to keep rates where they are until growth reaches 3% or 3.5% a year.

That could be Bailey’s legacy, for which the nation would thank him.

Friday, 15 May 2020

Goodhart’s law comes back to haunt the UK’s Covid strategy

Every so often, public policy provides a reason to discover or remember the value of Goodhart’s law. The UK’s response to coronavirus is a powerful and tragic example.

Named after Charles Goodhart, a financial guru, former chief economist of the Bank of England and a sheep farmer, the maxim is about the dangers of setting targets. When a useful measure becomes a target, the law states, it often ceases to be a good measure.

Mr Goodhart developed the law after observing how Margaret Thatcher’s government in the 1980s targeted the supply of money to control inflation but then found the monetary aggregates lost their previously strong relationship with inflation. Inflation ran out of control even when the government held a tight grip on the money supply.

What was true in 1980s UK economic policy is regularly experienced in the private sector. Far too often companies hit their top-down targets without improving underlying performance.

In the current crisis, target-setting is altogether more important. Early in March, Italy’s government strove to protect the nation’s health by locking down the Lombardy region. Initially, this led to a mini exodus that probably increased the spread of the disease to other parts of the country.

But it is in the UK where Goodhart’s law was most obviously overlooked. Throughout the crisis, “protect the NHS” has been the government’s core target. Along with “stay at home” it was the slogan repeated daily to “save lives”.

At first sight, nothing seemed amiss. Ensuring hospitals would not be overwhelmed seems so obviously necessary. Who would have wanted to see them starved of funds in a public health crisis? And their staff needed to be given all necessary equipment to battle the pandemic. With many weeks of experience, however, the slogan and associated numerical targets for making hospital beds available have been nothing short of a disaster. The evidence is overwhelming that instead of saving lives, they have cost them.

While the government focused on hospitals, care homes were given much less priority. Over the past five years between mid-March and the end of April, an average of 17,700 people have died in England and Wales’s care homes. This year, the total is just above 37,600. There is a debate over whether coronavirus was recklessly seeded into care homes when patients were moved there from hospitals. But there can be no doubt that relegating care homes to second division status contributed to the 19,900 excess deaths in the care sector.

Far more people than normal have also been dying at home and most of the excess deaths have not been classified as related to Covid-19 on death certificates. We do not yet know precisely why, but at the height of the crisis local doctors were asking their elderly patients to think hard about whether they really wanted to go to hospital or use the emergency services. A fit and sharp relative of mine received two of these calls.

The exact causal links will take time to establish. But 29,874 people have died at home since mid-March in England and Wales, 10,800 more than normal.

No one should think the government’s ambitions deliberately cost lives. But it was a deadly example of Goodhart’s law. The moment “protect the NHS” became the mantra, people dying elsewhere or without being tested didn’t count.

By comparison, the much criticised target of performing 100,000 coronavirus tests a day by the end of April was better conceived. Although the health department fiddled definitions to hit the goal for one day, earning a rebuke from the statistical regulator, the effort has left the UK better positioned for its ultimate objective of testing, tracking and isolating those with the virus.

Goodhart’s law always pops up in unexpected places. The failure in this crisis to think through the incentives created by the “protect the NHS” slogan will haunt Britain for many years.

Wednesday, 7 August 2019

Are Indian businessmen being unfairly targeted?

Monday, 26 November 2018

The difficulty in managing things that cannot easily be measured

If there were a tournament for Peter Drucker’s best-known dictum then “what gets measured gets managed” would make it to the finals, even though nobody seems able to pin the saying directly to the Viennese-born management thinker. Repeated misattribution has gilded the truism and propelled it into the Management Maxim Hall of Fame.

En route, unfortunately, the assumption has taken root that everything can be measured. Worse, anything that does not submit to mathematical evaluation need not be managed, or is simply unmanageable.

This is the most prominent example of a widespread phenomenon: the tendency to pay more attention to hard facts, targets, outcomes and initiatives than to soft factors that are equally, or sometimes more, important.

Big data is hard. Culture is soft. Financial goals are hard. Non-financial targets are soft. Gender quotas are hard. Workplace inclusivity is soft. “Stem” subjects are hard. Humanities are soft. (Drucker himself described management as a liberal art.) Machines are hard — very hard. Humans are all too soft.

The Harvard Business Review tries to reconcile the hard-soft tension annually in its ranking of the “best-performing CEOs in the world”, measured over their whole tenure. Jeff Bezos wins every time. Except he doesn’t, because in 2015, the publication changed its methodology and added soft environmental, social and governance factors to its hard financial assessment, knocking Amazon’s founder from first to 87th. Mr Bezos has crept back to 68th in the latest ranking, topped by Pablo Isla, chief executive of Spanish retail group Inditex with its (soft) family values. I bet, though, that most investors would allocate capital on the hard measures of Mr Bezos’s and Mr Isla’s success.

The dominance of hard over soft is not uniform, though, and in a few areas it is receding. Would-be leaders aiming for MBAs have for years set equal, even greater, store on the value of the difficult-to-measure human networks they build during their studies. The hard MBA qualification itself has started to crumble, while employers increasingly stress development of executives’ soft skills.

Elsewhere, companies have finally begun to realise that feedback (soft) trumps forced ranking and even bonuses (both hard) when it comes to appraising and motivating staff. Governance codes now place emphasis on long-term success, healthy cultures and corporate purpose, offsetting boards’ longstanding deference to pure shareholder value.

Many of these pairs should coexist, of course. Too frequently, though, when a balance of two approaches would be best, the hard solution wins out as soon as pressure is applied.

In the classic tussle between long-term sustainability and short-term returns, too many directors and executives still obsess about hitting close-range targets. Purpose makes way for profit. The demand to compete overcomes any impulse to reap the benefits of collaboration.

Even if Drucker did not utter the “what gets measured” axiom, he had plenty to say about measurement. In 1955, he wrote in The Practice of Management how more sophisticated ways of gauging performance would enable managers and workers to direct their own work. But he also warned that if this ability were used to impose control from above, “the new technology [would] inflict incalculable harm by demoralising management and by seriously lowering the effectiveness of managers”.

Persuading executives to take greater account of soft factors requires a concerted effort. One approach is to play to their utilitarian preference for hard facts and try to measure the unmeasurable. The mania for measurement has extended beyond the production output and profit margins that could be assessed in the 1950s. Start-ups and consultancies frequently pitch to me with new ways of quantifying corporate culture, for instance.

Putting a number on the nebulous is one way to give soft achievements a hard edge. Reminding directors of the hard landing that awaits those who ignore, condone or contribute to rotten cultures is another.

At the same time, managers need to comprehend elements that cannot yet be recorded in 0s and 1s: the strength of team relationships, the importance of empathy, the value of intuition. Ingenious machines may one day put all the mysteries of human behaviour into a spreadsheet. I doubt it, though. This week’s Drucker Forum, in honour of the writer, will explore “the human dimension” of management. At least some of that dimension will always be difficult for chief executives to collect, crunch and codify on their digital dashboards. As a result, they must resolve to try harder to manage the things they will never easily measure.

Sunday, 29 April 2018

The Tories keep getting blamed for the terrible events they caused. To be honest, it’s out of order

Amber Rudd says she finds the cases of families who were threatened with deportation, and harangued for documents they never had, “heartbreaking”. So she deserves respect for having the strength to carry on, while she suffers from a broken heart like that.

She also denies there was ever a “target” for removing immigrants, so we can only imagine how poignant a moment it must have been, when she was told “home secretary, you know when your government boasted before the 2015 (actually 2010 election) election it would ‘cut net migration to tens of thousands’? And an Inspection Report stated there was a ‘target of removing 12,000 immigrants?’ It turns out some people in the immigration office interpreted that as implying there was some sort of target.”

She must have cried and cried and howled, sniffing, “I know it sounds silly, but I can’t help feeling that makes this government partly responsible.”

Hopefully she’ll have had plenty of friends consoling her, saying reassuringly: “Oh home secretary, you mustn’t blame yourself. All of us set targets for removing people, regardless of the fact we’ve been told by an array of institutions this will cause appalling hardship to innocent people. You’re a good person. Stay strong, Amber, stay strong.”

So she’s proved her leadership qualities and overcome the heartbreak she feels so deeply, to explain: “We are deeply bountifully humongously sorry, but I would remind the country that three years ago, we thought it was popular to scream about chucking out piles of immigrants, so we can hardly be blamed if that has turned out not to be true after all. Now if you’ll forgive me, I must take some more antidepressants. I’m heartbroken you see.”

Theresa May must be even more heartbroken, because she was home secretary at the time. Some people suggest this means she had some knowledge of the targets, but that would be unfair, as she was busy sending out vans with signs on the side saying “illegal immigrants, go home”, so she can’t have had time to write down lots of numbers as well.

But now they love Caribbean people so it’s worked out fine in the end. Soon Amber Rudd will feature on a dancehall track with Shaggy, about the Windrush families, that starts “Dem tell I sad tale dat send chill trew I blood, Me weep so many tear dey call I Heartbreak Rudd.”

And the prime minister will end her apology by saying “I would now like to repeat my message for my Caribbean bredren. Listen up rude boy, me send out one love for me have pain in I ‘eart. But blame be upon dem raasclat immigration official, for me is vexed upon why dey carry out act what I tell dem do, Selasie I.”

She must feel even worse than Amber Rudd, because last year she made speeches such as “Brexit must mean control of the number of people who come to Britain. And that is what we will deliver.”

It would be ridiculous to imagine this was designed to create the impression she was in a rush to cut immigration, which was why Conservative Party spokespeople sometimes mentioned cutting immigration as few as 46 times in a three-minute interview.

Sometimes, if a minister was asked for a statement about the standards of maths in schools, or whether England would ever win the World Cup, they wouldn’t even mention their pledge to be tough on immigration until the ninth word.

So it’s a puzzle how anyone in the immigration office got the impression they were required to be a little bit zealous in the area of immigration.

It’s possible a pattern could emerge here, in which Conservatives start to feel sorry about other matters that they get unfairly blamed for just because they caused them.

For example, they’re dreadfully shocked about the lack of health and safety regulations in housing, even though David Cameron can’t possibly have predicted that his pledge to create a “bonfire of regulations” might lead to a reduction of regulations.

Iain Duncan-Smith will declare he’s appalled by stories of disabled people having their benefits stopped after being declared “fit for work”, when he can’t possibly have known this was going on, which is why he’s “truly awfully shocked and immeasurably saddened and exploding with volcanic sadness”.

Then they’ll announce they are devastated by the revelation that cutting benefits for the poorest people while asking the wealthiest people for less in tax made the poor poorer and the rich richer.

But they will add that cutting the top rate of tax was in no way designed to lower the top rate of tax, and they certainly don’t ever remember setting a target to cut the top rate of tax. It was probably down to some heartless tax official, and he’ll be in right trouble when they catch him.

But much of the Labour Party must be on Valium as well. Because throughout the years of the coalition, they went along with many of these measures. They were so concerned to appear tough on immigration that they had special mugs made, saying “I’m voting Labour, for controls on immigration.”

If they’d had the money, they would probably have made other household goods with the same message, such as toilet rolls and Ventolin inhalers. The Labour leaders from that time must be heartbroken.

So they should make one joint statement together, to cover all their heartbreak, that goes: “We’re really sorry, we had no idea our policy of being proudly, relentlessly foul would lead to any foulness.

“When one lot screamed, ‘Vote for us because we’re really foul’ and the other lot shouted, ‘That’s not fair, we’re quite capable of being disgustingly foul’, we didn’t know we’d misjudged the situation and foulness wouldn’t always be popular. So we’re all really really sorry, even though it’s not in any way in the slightest tiddly bit our fault.”

Sunday, 4 December 2016

Are women evil? - Google, democracy and the truth about internet search

Here’s what you don’t want to do late on a Sunday night. You do not want to type seven letters into Google. That’s all I did. I typed: “a-r-e”. And then “j-e-w-s”. Since 2008, Google has attempted to predict what question you might be asking and offers you a choice. And this is what it did. It offered me a choice of potential questions it thought I might want to ask: “are jews a race?”, “are jews white?”, “are jews christians?”, and finally, “are jews evil?”

Are Jews evil? It’s not a question I’ve ever thought of asking. I hadn’t gone looking for it. But there it was. I press enter. A page of results appears. This was Google’s question. And this was Google’s answer: Jews are evil. Because there, on my screen, was the proof: an entire page of results, nine out of 10 of which “confirm” this. The top result, from a site called Listovative, has the headline: “Top 10 Major Reasons Why People Hate Jews.” I click on it: “Jews today have taken over marketing, militia, medicinal, technological, media, industrial, cinema challenges etc and continue to face the worlds [sic] envy through unexplained success stories given their inglorious past and vermin like repression all over Europe.”

Google is search. It’s the verb, to Google. It’s what we all do, all the time, whenever we want to know anything. We Google it. The site handles at least 63,000 searches a second, 5.5bn a day. Its mission as a company, the one-line overview that has informed the company since its foundation and is still the banner headline on its corporate website today, is to “organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”. It strives to give you the best, most relevant results. And in this instance the third-best, most relevant result to the search query “are Jews… ” is a link to an article from stormfront.org, a neo-Nazi website. The fifth is a YouTube video: “Why the Jews are Evil. Why we are against them.”

The sixth is from Yahoo Answers: “Why are Jews so evil?” The seventh result is: “Jews are demonic souls from a different world.” And the 10th is from jesus-is-saviour.com: “Judaism is Satanic!”

There’s one result in the 10 that offers a different point of view. It’s a link to a rather dense, scholarly book review from thetabletmag.com, a Jewish magazine, with the unfortunately misleading headline: “Why Literally Everybody In the World Hates Jews.”

I feel like I’ve fallen down a wormhole, entered some parallel universe where black is white, and good is bad. Though later, I think that perhaps what I’ve actually done is scraped the topsoil off the surface of 2016 and found one of the underground springs that has been quietly nurturing it. It’s been there all the time, of course. Just a few keystrokes away… on our laptops, our tablets, our phones. This isn’t a secret Nazi cell lurking in the shadows. It’s hiding in plain sight.

Are women… Google’s search results.

Stories about fake news on Facebook have dominated certain sections of the press for weeks following the American presidential election, but arguably this is even more powerful, more insidious. Frank Pasquale, professor of law at the University of Maryland, and one of the leading academic figures calling for tech companies to be more open and transparent, calls the results “very profound, very troubling”.

He came across a similar instance in 2006 when, “If you typed ‘Jew’ in Google, the first result was jewwatch.org. It was ‘look out for these awful Jews who are ruining your life’. And the Anti-Defamation League went after them and so they put an asterisk next to it which said: ‘These search results may be disturbing but this is an automated process.’ But what you’re showing – and I’m very glad you are documenting it and screenshotting it – is that despite the fact they have vastly researched this problem, it has gotten vastly worse.”

And ordering of search results does influence people, says Martin Moore, director of the Centre for the Study of Media, Communication and Power at King’s College, London, who has written at length on the impact of the big tech companies on our civic and political spheres. “There’s large-scale, statistically significant research into the impact of search results on political views. And the way in which you see the results and the types of results you see on the page necessarily has an impact on your perspective.” Fake news, he says, has simply “revealed a much bigger problem. These companies are so powerful and so committed to disruption. They thought they were disrupting politics but in a positive way. They hadn’t thought about the downsides. These tools offer remarkable empowerment, but there’s a dark side to it. It enables people to do very cynical, damaging things.”

Google is knowledge. It’s where you go to find things out. And evil Jews are just the start of it. There are also evil women. I didn’t go looking for them either. This is what I type: “a-r-e w-o-m-e-n”. And Google offers me just two choices, the first of which is: “Are women evil?” I press return. Yes, they are. Every one of the 10 results “confirms” that they are, including the top one, from a site called sheddingoftheego.com, which is boxed out and highlighted: “Every woman has some degree of prostitute in her. Every woman has a little evil in her… Women don’t love men, they love what they can do for them. It is within reason to say women feel attraction but they cannot love men.”

Next I type: “a-r-e m-u-s-l-i-m-s”. And Google suggests I should ask: “Are Muslims bad?” And here’s what I find out: yes, they are. That’s what the top result says and six of the others. Without typing anything else, simply putting the cursor in the search box, Google offers me two new searches and I go for the first, “Islam is bad for society”. In the next list of suggestions, I’m offered: “Islam must be destroyed.”

Jews are evil. Muslims need to be eradicated. And Hitler? Do you want to know about Hitler? Let’s Google it. “Was Hitler bad?” I type. And here’s Google’s top result: “10 Reasons Why Hitler Was One Of The Good Guys” I click on the link: “He never wanted to kill any Jews”; “he cared about conditions for Jews in the work camps”; “he implemented social and cultural reform.” Eight out of the other 10 search results agree: Hitler really wasn’t that bad.

A few days later, I talk to Danny Sullivan, the founding editor of SearchEngineLand.com. He’s been recommended to me by several academics as one of the most knowledgeable experts on search. Am I just being naive, I ask him? Should I have known this was out there? “No, you’re not being naive,” he says. “This is awful. It’s horrible. It’s the equivalent of going into a library and asking a librarian about Judaism and being handed 10 books of hate. Google is doing a horrible, horrible job of delivering answers here. It can and should do better.”

He’s surprised too. “I thought they stopped offering autocomplete suggestions for religions in 2011.” And then he types “are women” into his own computer. “Good lord! That answer at the top. It’s a featured result. It’s called a “direct answer”. This is supposed to be indisputable. It’s Google’s highest endorsement.” That every women has some degree of prostitute in her? “Yes. This is Google’s algorithm going terribly wrong.”

I contacted Google about its seemingly malfunctioning autocomplete suggestions and received the following response: “Our search results are a reflection of the content across the web. This means that sometimes unpleasant portrayals of sensitive subject matter online can affect what search results appear for a given query. These results don’t reflect Google’s own opinions or beliefs – as a company, we strongly value a diversity of perspectives, ideas and cultures.”

Google isn’t just a search engine, of course. Search was the foundation of the company but that was just the beginning. Alphabet, Google’s parent company, now has the greatest concentration of artificial intelligence experts in the world. It is expanding into healthcare, transportation, energy. It’s able to attract the world’s top computer scientists, physicists and engineers. It’s bought hundreds of start-ups, including Calico, whose stated mission is to “cure death” and DeepMind, which aims to “solve intelligence”.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin in 2002. Photograph: Michael Grecco/Getty Images

And 20 years ago it didn’t even exist. When Tony Blair became prime minister, it wasn’t possible to Google him: the search engine had yet to be invented. The company was only founded in 1998 and Facebook didn’t appear until 2004. Google’s founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page are still only 43. Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook is 32. Everything they’ve done, the world they’ve remade, has been done in the blink of an eye.

But it seems the implications about the power and reach of these companies is only now seeping into the public consciousness. I ask Rebecca MacKinnon, director of the Ranking Digital Rights project at the New America Foundation, whether it was the recent furore over fake news that woke people up to the danger of ceding our rights as citizens to corporations. “It’s kind of weird right now,” she says, “because people are finally saying, ‘Gee, Facebook and Google really have a lot of power’ like it’s this big revelation. And it’s like, ‘D’oh.’”

MacKinnon has a particular expertise in how authoritarian governments adapt to the internet and bend it to their purposes. “China and Russia are a cautionary tale for us. I think what happens is that it goes back and forth. So during the Arab spring, it seemed like the good guys were further ahead. And now it seems like the bad guys are. Pro-democracy activists are using the internet more than ever but at the same time, the adversary has gotten so much more skilled.”

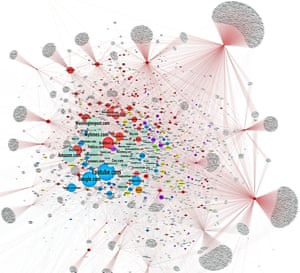

Last week Jonathan Albright, an assistant professor of communications at Elon University in North Carolina, published the first detailed research on how rightwing websites had spread their message. “I took a list of these fake news sites that was circulating, I had an initial list of 306 of them and I used a tool – like the one Google uses – to scrape them for links and then I mapped them. So I looked at where the links went – into YouTube and Facebook, and between each other, millions of them… and I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing.

“They have created a web that is bleeding through on to our web. This isn’t a conspiracy. There isn’t one person who’s created this. It’s a vast system of hundreds of different sites that are using all the same tricks that all websites use. They’re sending out thousands of links to other sites and together this has created a vast satellite system of rightwing news and propaganda that has completely surrounded the mainstream media system.

He found 23,000 pages and 1.3m hyperlinks. “And Facebook is just the amplification device. When you look at it in 3D, it actually looks like a virus. And Facebook was just one of the hosts for the virus that helps it spread faster. You can see the New York Times in there and the Washington Post and then you can see how there’s a vast, vast network surrounding them. The best way of describing it is as an ecosystem. This really goes way beyond individual sites or individual stories. What this map shows is the distribution network and you can see that it’s surrounding and actually choking the mainstream news ecosystem.”

Like a cancer? “Like an organism that is growing and getting stronger all the time.”

Charlie Beckett, a professor in the school of media and communications at LSE, tells me: “We’ve been arguing for some time now that plurality of news media is good. Diversity is good. Critiquing the mainstream media is good. But now… it’s gone wildly out of control. What Jonathan Albright’s research has shown is that this isn’t a byproduct of the internet. And it’s not even being done for commercial reasons. It’s motivated by ideology, by people who are quite deliberately trying to destabilise the internet.”

A spatial map of the rightwing fake news ecosystem. Jonathan Albright, assistant professor of communications at Elon University, North Carolina, “scraped” 300 fake news sites (the dark shapes on this map) to reveal the 1.3m hyperlinks that connect them together and link them into the mainstream news ecosystem. Here, Albright shows it is a “vast satellite system of rightwing news and propaganda that has completely surrounded the mainstream media system”. Photograph: Jonathan Albright

Albright’s map also provides a clue to understanding the Google search results I found. What these rightwing news sites have done, he explains, is what most commercial websites try to do. They try to find the tricks that will move them up Google’s PageRank system. They try and “game” the algorithm. And what his map shows is how well they’re doing that.

That’s what my searches are showing too. That the right has colonised the digital space around these subjects – Muslims, women, Jews, the Holocaust, black people – far more effectively than the liberal left.

“It’s an information war,” says Albright. “That’s what I keep coming back to.”

But it’s where it goes from here that’s truly frightening. I ask him how it can be stopped. “I don’t know. I’m not sure it can be. It’s a network. It’s far more powerful than any one actor.”

So, it’s almost got a life of its own? “Yes, and it’s learning. Every day, it’s getting stronger.”

The more people who search for information about Jews, the more people will see links to hate sites, and the more they click on those links (very few people click on to the second page of results) the more traffic the sites will get, the more links they will accrue and the more authoritative they will appear. This is an entirely circular knowledge economy that has only one outcome: an amplification of the message. Jews are evil. Women are evil. Islam must be destroyed. Hitler was one of the good guys.

And the constellation of websites that Albright found – a sort of shadow internet – has another function. More than just spreading rightwing ideology, they are being used to track and monitor and influence anyone who comes across their content. “I scraped the trackers on these sites and I was absolutely dumbfounded. Every time someone likes one of these posts on Facebook or visits one of these websites, the scripts are then following you around the web. And this enables data-mining and influencing companies like Cambridge Analytica to precisely target individuals, to follow them around the web, and to send them highly personalised political messages. This is a propaganda machine. It’s targeting people individually to recruit them to an idea. It’s a level of social engineering that I’ve never seen before. They’re capturing people and then keeping them on an emotional leash and never letting them go.”

Cambridge Analytica, an American-owned company based in London, was employed by both the Vote Leave campaign and the Trump campaign. Dominic Cummings, the campaign director of Vote Leave, has made few public announcements since the Brexit referendum but he did say this: “If you want to make big improvements in communication, my advice is – hire physicists.”

Steve Bannon, founder of Breitbart News and the newly appointed chief strategist to Trump, is on Cambridge Analytica’s board and it has emerged that the company is in talks to undertake political messaging work for the Trump administration. It claims to have built psychological profiles using 5,000 separate pieces of data on 220 million American voters. It knows their quirks and nuances and daily habits and can target them individually.

“They were using 40-50,000 different variants of ad every day that were continuously measuring responses and then adapting and evolving based on that response,” says Martin Moore of Kings College. Because they have so much data on individuals and they use such phenomenally powerful distribution networks, they allow campaigns to bypass a lot of existing laws.

“It’s all done completely opaquely and they can spend as much money as they like on particular locations because you can focus on a five-mile radius or even a single demographic. Fake news is important but it’s only one part of it. These companies have found a way of transgressing 150 years of legislation that we’ve developed to make elections fair and open.”

Did such micro-targeted propaganda – currently legal – swing the Brexit vote? We have no way of knowing. Did the same methods used by Cambridge Analytica help Trump to victory? Again, we have no way of knowing. This is all happening in complete darkness. We have no way of knowing how our personal data is being mined and used to influence us. We don’t realise that the Facebook page we are looking at, the Google page, the ads that we are seeing, the search results we are using, are all being personalised to us. We don’t see it because we have nothing to compare it to. And it is not being monitored or recorded. It is not being regulated. We are inside a machine and we simply have no way of seeing the controls. Most of the time, we don’t even realise that there are controls.

Facebook and Google move to kick fake news sites off their ad networks

Rebecca MacKinnon says that most of us consider the internet to be like “the air that we breathe and the water that we drink”. It surrounds us. We use it. And we don’t question it. “But this is not a natural landscape. Programmers and executives and editors and designers, they make this landscape. They are human beings and they all make choices.”

But we don’t know what choices they are making. Neither Google or Facebook make their algorithms public. Why did my Google search return nine out of 10 search results that claim Jews are evil? We don’t know and we have no way of knowing. Their systems are what Frank Pasquale describes as “black boxes”. He calls Google and Facebook “a terrifying duopoly of power” and has been leading a growing movement of academics who are calling for “algorithmic accountability”. “We need to have regular audits of these systems,” he says. “We need people in these companies to be accountable. In the US, under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, every company has to have a spokesman you can reach. And this is what needs to happen. They need to respond to complaints about hate speech, about bias.”

Is bias built into the system? Does it affect the kind of results that I was seeing? “There’s all sorts of bias about what counts as a legitimate source of information and how that’s weighted. There’s enormous commercial bias. And when you look at the personnel, they are young, white and perhaps Asian, but not black or Hispanic and they are overwhelmingly men. The worldview of young wealthy white men informs all these judgments.”

Later, I speak to Robert Epstein, a research psychologist at the American Institute for Behavioural Research and Technology, and the author of the study that Martin Moore told me about (and that Google has publicly criticised), showing how search-rank results affect voting patterns. On the other end of the phone, he repeats one of the searches I did. He types “do blacks…” into Google.

“Look at that. I haven’t even hit a button and it’s automatically populated the page with answers to the query: ‘Do blacks commit more crimes?’ And look, I could have been going to ask all sorts of questions. ‘Do blacks excel at sports’, or anything. And it’s only given me two choices and these aren’t simply search-based or the most searched terms right now. Google used to use that but now they use an algorithm that looks at other things. Now, let me look at Bing and Yahoo. I’m on Yahoo and I have 10 suggestions, not one of which is ‘Do black people commit more crime?’

“And people don’t question this. Google isn’t just offering a suggestion. This is a negative suggestion and we know that negative suggestions depending on lots of things can draw between five and 15 more clicks. And this all programmed. And it could be programmed differently.”

What Epstein’s work has shown is that the contents of a page of search results can influence people’s views and opinions. The type and order of search rankings was shown to influence voters in India in double-blind trials. There were similar results relating to the search suggestions you are offered.

“The general public are completely in the dark about very fundamental issues regarding online search and influence. We are talking about the most powerful mind-control machine ever invented in the history of the human race. And people don’t even notice it.”

Damien Tambini, an associate professor at the London School of Economics, who focuses on media regulation, says that we lack any sort of framework to deal with the potential impact of these companies on the democratic process. “We have structures that deal with powerful media corporations. We have competition laws. But these companies are not being held responsible. There are no powers to get Google or Facebook to disclose anything. There’s an editorial function to Google and Facebook but it’s being done by sophisticated algorithms. They say it’s machines not editors. But that’s simply a mechanised editorial function.”

And the companies, says John Naughton, the Observer columnist and a senior research fellow at Cambridge University, are terrified of acquiring editorial responsibilities they don’t want. “Though they can and regularly do tweak the results in all sorts of ways.”

Certainly the results about Google on Google don’t seem entirely neutral. Google “Is Google racist?” and the featured result – the Google answer boxed out at the top of the page – is quite clear: no. It is not.

But the enormity and complexity of having two global companies of a kind we have never seen before influencing so many areas of our lives is such, says Naughton, that “we don’t even have the mental apparatus to even know what the problems are”.

And this is especially true of the future. Google and Facebook are at the forefront of AI. They are going to own the future. And the rest of us can barely start to frame the sorts of questions we ought to be asking. “Politicians don’t think long term. And corporations don’t think long term because they’re focused on the next quarterly results and that’s what makes Google and Facebook interesting and different. They are absolutely thinking long term. They have the resources, the money, and the ambition to do whatever they want.

“They want to digitise every book in the world: they do it. They want to build a self-driving car: they do it. The fact that people are reading about these fake news stories and realising that this could have an effect on politics and elections, it’s like, ‘Which planet have you been living on?’ For Christ’s sake, this is obvious.”

“The internet is among the few things that humans have built that they don’t understand.” It is “the largest experiment involving anarchy in history. Hundreds of millions of people are, each minute, creating and consuming an untold amount of digital content in an online world that is not truly bound by terrestrial laws.” The internet as a lawless anarchic state? A massive human experiment with no checks and balances and untold potential consequences? What kind of digital doom-mongerer would say such a thing? Step forward, Eric Schmidt – Google’s chairman. They are the first lines of the book, The New Digital Age, that he wrote with Jared Cohen.

We don’t understand it. It is not bound by terrestrial laws. And it’s in the hands of two massive, all-powerful corporations. It’s their experiment, not ours. The technology that was supposed to set us free may well have helped Trump to power, or covertly helped swing votes for Brexit. It has created a vast network of propaganda that has encroached like a cancer across the entire internet. This is a technology that has enabled the likes of Cambridge Analytica to create political messages uniquely tailored to you. They understand your emotional responses and how to trigger them. They know your likes, dislikes, where you live, what you eat, what makes you laugh, what makes you cry.

And what next? Rebecca MacKinnon’s research has shown how authoritarian regimes reshape the internet for their own purposes. Is that what’s going to happen with Silicon Valley and Trump? As Martin Moore points out, the president-elect claimed that Apple chief executive Tim Cook called to congratulate him soon after his election victory. “And there will undoubtedly be be pressure on them to collaborate,” says Moore.

Journalism is failing in the face of such change and is only going to fail further. New platforms have put a bomb under the financial model – advertising – resources are shrinking, traffic is increasingly dependent on them, and publishers have no access, no insight at all, into what these platforms are doing in their headquarters, their labs. And now they are moving beyond the digital world into the physical. The next frontiers are healthcare, transportation, energy. And just as Google is a near-monopoly for search, its ambition to own and control the physical infrastructure of our lives is what’s coming next. It already owns our data and with it our identity. What will it mean when it moves into all the other areas of our lives?

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg: still only 32 years of age. Photograph: Mariana Bazo/Reuters

“At the moment, there’s a distance when you Google ‘Jews are’ and get ‘Jews are evil’,” says Julia Powles, a researcher at Cambridge on technology and law. “But when you move into the physical realm, and these concepts become part of the tools being deployed when you navigate around your city or influence how people are employed, I think that has really pernicious consequences.”

Powles is shortly to publish a paper looking at DeepMind’s relationship with the NHS. “A year ago, 2 million Londoners’ NHS health records were handed over to DeepMind. And there was complete silence from politicians, from regulators, from anyone in a position of power. This is a company without any healthcare experience being given unprecedented access into the NHS and it took seven months to even know that they had the data. And that took investigative journalism to find it out.”

The headline was that DeepMind was going to work with the NHS to develop an app that would provide early warning for sufferers of kidney disease. And it is, but DeepMind’s ambitions – “to solve intelligence” – goes way beyond that. The entire history of 2 million NHS patients is, for artificial intelligence researchers, a treasure trove. And, their entry into the NHS – providing useful services in exchange for our personal data – is another massive step in their power and influence in every part of our lives.

Because the stage beyond search is prediction. Google wants to know what you want before you know yourself. “That’s the next stage,” says Martin Moore. “We talk about the omniscience of these tech giants, but that omniscience takes a huge step forward again if they are able to predict. And that’s where they want to go. To predict diseases in health. It’s really, really problematic.”

For the nearly 20 years that Google has been in existence, our view of the company has been inflected by the youth and liberal outlook of its founders. Ditto Facebook, whose mission, Zuckberg said, was not to be “a company. It was built to accomplish a social mission to make the world more open and connected.”

It would be interesting to know how he thinks that’s working out. Donald Trump is connecting through exactly the same technology platforms that supposedly helped fuel the Arab spring; connecting to racists and xenophobes. And Facebook and Google are amplifying and spreading that message. And us too – the mainstream media. Our outrage is just another node on Jonathan Albright’s data map.

“The more we argue with them, the more they know about us,” he says. “It all feeds into a circular system. What we’re seeing here is new era of network propaganda.”

We are all points on that map. And our complicity, our credulity, being consumers not concerned citizens, is an essential part of that process. And what happens next is down to us. “I would say that everybody has been really naive and we need to reset ourselves to a much more cynical place and proceed on that basis,” is Rebecca MacKinnon’s advice. “There is no doubt that where we are now is a very bad place. But it’s we as a society who have jointly created this problem. And if we want to get to a better place, when it comes to having an information ecosystem that serves human rights and democracy instead of destroying it, we have to share responsibility for that.”

Are Jews evil? How do you want that question answered? This is our internet. Not Google’s. Not Facebook’s. Not rightwing propagandists. And we’re the only ones who can reclaim it.

Sunday, 9 March 2014

On the NHS frontline: 'being a doctor in A&E is like being a medic in a war zone'

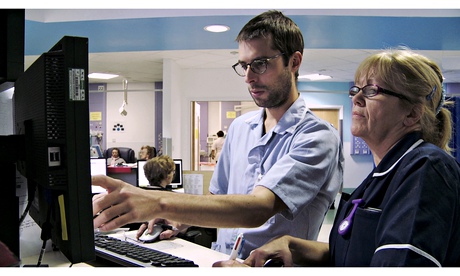

The A&E department at Queen's hospital in Romford deals with 400 patients a day.

The A&E department at Queen's hospital in Romford deals with 400 patients a day. Medics with a patient at Queen's hospital. The hospital was built for 90,000 patients a year but receives 140,000.

Medics with a patient at Queen's hospital. The hospital was built for 90,000 patients a year but receives 140,000. Staff at work at Queen's hospital. The hospital has only eight full-time consultants.

Staff at work at Queen's hospital. The hospital has only eight full-time consultants.