Doctor explains why she decided to make a film depicting the real-life drama of targets and staff pushed to the limit

The start of a shift and I brace myself as I walk into the waiting area. A huge number of people are already there, waiting to be called. I try to avoid eye contact. It's like entering an arena but I feel more like the sacrificial lamb than a gladiator. Entering the main area of the emergency department, a scene of chaos. All available space to see patients is occupied. Staff shout instructions to each other above the noise. I hear a patient vomiting, another is crying out in pain and an elderly woman's voice cuts through, confused and repeating that she wants to go home. "So do I," I whisper to myself.

Colleagues run between cubicles with clean sheets, urine pots and trays for taking blood. Ambulance sirens heard above the noise signal that more patients are coming. A cardiac arrest case is sped into the resuscitation room with paramedics pumping the chest of a patient as the rest of the crash team run through. The atmosphere is explosive and adrenaline charged.

A senior doctor in the middle of the storm tries to bring order in a place that refuses to be controlled. Junior doctors are flushed, red in the face, eyes wide with a hint of panic. I find a tearful one at the computer. She is new and hating every second of it. There isn't time or even space to console her with a pep talk. Give her a few more weeks and the hard outer shell will develop like body armour.

My first patient of the shift needs a full neurological exam. I hunt around for a pen torch to shine into her eyes. "Make sure you have your weapons before you go to war," says a fellow registrar, wryly, handing over the torch. I smile. This is not Palestine, Libya or Syria. This is a hospital on the eastern outskirts of London.

The A&E department at Queen's hospital in Romford deals with 400 patients a day.

The A&E department at Queen's hospital in Romford deals with 400 patients a day.

Being a doctor in accident and emergency has at times resembled being a medic in a war zone. I have worked as a doctor in various conflicts and yet some of my most stressful moments, facing a tidal wave of pressure, have happened closer to home, in Queen's hospital, Romford.

The UK's A&E departments have been described by the College of Emergency Medicine (CEM) as facing a crisis. The term was specifically chosen to describe the situation that everyone from the most senior consultant to the most junior nurse is experiencing. Last year Dr Cliff Mann, the CEM president, wrote in a press release: "A lack of a plan for resolution [is] an existential threat to emergency medicine."

There are recurrent themes causing the crisis: more people are coming to A&E; a falling number of doctors want to work there because of the pressures involved and the poor work/life balance; and hospitals are increasingly full – resulting in bottlenecks that back up into the emergency department.

Over the past four progressively worse winters I came to a tipping point. Nothing in the media was reflecting the daily realities of being a doctor on the shop floor. Last April, when the CEM's press release hit the headlines, I took my cue.

I divide my time as an A&E doctor and film-maker. I wanted to make something honest and reflective of the reality.

After a year's worth of access negotiation, I began filming with the Guardian this winter in two hospitals – Queen's where I work as a middle-grade locum, and Musgrove Park, in Taunton, Somerset, where Cliff Mann also works.

"For a long time we were like John the Baptist, crying into the wilderness and no one was listening," Mann said to me, while on shift at Musgrove Park. The most senior consultant within emergency medicine leads from the front, including a Friday shift that runs from 3pm to midnight. "No one goes into emergency medicine thinking it's going to be easy and calm – that would be bizarre. But if you push the individual with persistently increasing intensity levels they will start to fade."

The TV stories of George Clooney and the ER cast don't come close to reality. My research into the speciality obviously went beyond watching medical dramas but nothing prepared me for what it was actually like.

Attending conferences in emergency medicine becomes almost therapeutic in its sharing of experiences. At an emergency medicine conference, Expanding Scientific Horizons, held in Twickenham, south-west London, last year, it was telling that the sessions entitled Creating Satisfaction and Maintaining Wellbeing in Emergency Medicine were standing room only.

One of the speakers, Susie Hewitt, a consultant from Derby, spoke about her battle with depression during the time she was appointed head of service for the introduction of the four-hour target – the government's instruction that 95% of patients should be seen within four hours of arriving at A&E.

The culmination of work and personal pressures resulted in what Hewitt describes as being "hit with what felt like a big freight train".

Many of us recognised ourselves in that. At the conference leaflets for well-being support and therapies were being distributed widely. We are clearly not a very healthy bunch right now.

The CEM warned the government three years ago that there was a problem with falling numbers of staff, but no concrete solutions emerged. I began to see my own consultants and middle-grade colleagues make plans to fly to the other side of the world.

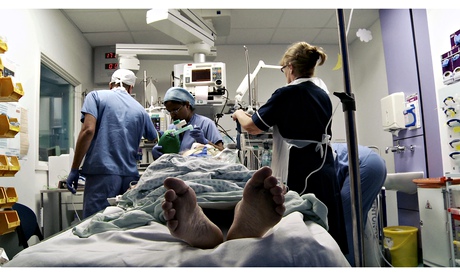

Medics with a patient at Queen's hospital. The hospital was built for 90,000 patients a year but receives 140,000.

Medics with a patient at Queen's hospital. The hospital was built for 90,000 patients a year but receives 140,000.

Queen's A&E, part of the Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Trust, sees about 400 patients a day and its sister hospital, King George's, sees 200. The trust serves a population of 750,000 and is one of the UK's largest. It also has one of the highest elderly populations in London. Following a report by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) that its A&E was "at times unsafe because of the lack of full-time consultants and middle-grade doctors", Queen's became the 14th hospital to be put into special measures last December. Filming with the Guardian inside its A&E began the next day.

The hospital was built for 90,000 patients a year but receives 140,000. Ironically, King George's A&E, which performs better against targets, is scheduled for closure in 2015, after a unanimous vote by local primary care trusts. Queen's is expected to absorb the extra numbers. Queen's is understaffed, with only eight full-time consultants where it requires 21 in order to provide 24-hour cover, seven days a week. Four consultants left last year.

One of them, Dr Rosie Furse, described the pressure of targets. Battles with certain specialities to accept patients on to their wards are also a common complaint. She left for a post on the island of Mustique before being recruited to a hospital in Bath.

David Prior, chairman of the CQC, was reported in the Guardian in May 2013 as saying too many patients were arriving at hospital as emergency cases, and improved earlier care in the community was needed. He suggested more acute beds should be closed. "Emergency admissions through accident and emergency are out of control in large parts of the country," he said.

That prompted memories of a recent bed-blocked day in Queen's. Matron Mary Feeney rushed into A&E having secured a bed on the intensive therapy unit for an unwell patient in an A&E cubicle.

"They say bring him in half an hour – half an hour we have not got," and with that the patient was out of the door on the way with matron off to negotiate access at the hallowed gates of ITU.

A significant contributor to breaches of the four-hour target is the quest to find a bed for someone who is clearly not well enough to go home. Over Christmas one woman was brought in with diarrhoea and a ruptured bowel requiring a surgical side room. She waited in A&E for 17 hours until a room became available. Another woman was brought in with high blood sugars and needed an acute medical bed. I saw her when she arrived in the evening and then met her the next morning when I came back to work. That's when A&E becomes a ward.

On the first day of filming we had four intubated, unconscious patients in the resuscitation room at the same time, all of them requiring critical beds. The rest of the room was full of acutely unwell patients being redistributed around A&E as more room was needed with each new ambulance arrival.

Finding alternatives to A&E through improved care in the community is essential but if more acute beds close the A&E waits will get longer for sick patients requiring admission.

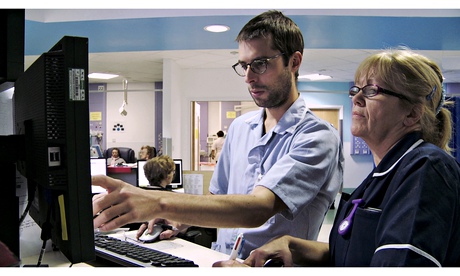

Staff at work at Queen's hospital. The hospital has only eight full-time consultants.

Staff at work at Queen's hospital. The hospital has only eight full-time consultants.

I went through a period of having palpitations during a stretch of extremely challenging shifts last winter. It was when I had a palpitation and nearly passed out while driving that I decided to step down my intensity of work. I had further investigations but the remedy was obvious. I reduced my shifts and the palpitations have stopped.

Over the past three years I have worked harder than in my previous life in the army. I went through the Sandhurst commissioning course, renowned for its tough schedule, but in accident and emergency medicine at its peak, the intensity is tougher.

The CEM published an aptly named report – Stretched to the limit – in October last year. It described a consultant workforce under pressure. As a middle grade I wonder if actually I can physically do the job of a consultant.

The report said: "Evidence confirms that burnout among physicians in emergency medicine occurs at the highest rate of all medical specialities. There is also a very worrying trend developing of consultants seeking to move abroad after having been trained in the NHS."

The report details 21 consultants having left the UK in 2013 with an overall exodus of 78 since 2008.

Within the report details of a survey reveal that consultants on average plan to retire at 60 with the current job not compatible with advancing age. "Doing four nights in a row when you are 50 or 55 is physically impossible," said Dr Antoine Azzi, a specialist registrar working at Queen's at the very end of his training and soon to be a consultant.

He hopes for a less intense workload as a consultant, but it appears that is not going to be the case. The report said that 40% of the consultant workforce were on call one night in every six. The average age of emergency medicine consultants is 43 and the survey showed most plan to retire at 60.

The things that make a difference include access to training, which provides juniors with skills they need and reduces a layer of stress.

Before she left, Furse, like many other consultants, was dedicated to improving the working lives of her trainees and colleagues.

On one occasion I placed a chest drain into a patient with a spontaneous pneumothorax – a collection of air between the lung and the chest wall. If I failed, he could go into respiratory arrest, which could lead to death.

Furse stood by, calm and instructive. "Get it in quick, Saleyha," was all she said. I urged the drain's tube into his chest and the moment I saw the swinging bubble of the drain, signalling a successful placement I allowed myself to breathe and the patient was stabilised.

Moments like that are what makes being a doctor count but opportunities for training are few as workload grows.

The constant turnover of new junior doctors hits the department, too. Most junior doctors who spend six months in A&E leave at the end of their assignment with a lot of experience, but they are relieved to be going and they won't be coming back.

Mann says: "They come and do their six-month attachment and at the end say, "Thank you very much, it was interesting but I am moving on because it nearly killed me.'"

There is a quote from Hippocrates that says: "Where there is a love of medicine, there is a love of humanity." I see this every day to some degree in A&E. Before she left Furse reminded us during a teaching session: "Patients are key to everything we do and if you stop caring about them – well you should not be here any more."

Looking back on diary entries related to shifts I did last year during the spell when I was having palpitations I was reminded why I put myself through it. It's what makes us go back the next day no matter how awful the shift has been.

I wrote: "It was hard, I am tired and I was pushed but I feel alive. Today counted. I cared for patients and they remained the main focus of my day. Nothing else. Patients arrive here to be seen on possibly the worst days of their lives and through them we learn so much about our art. They teach us how to be doctors. As I walked into work today I was hit by reflection of all the patients who have left their mark – the ones that didn't make it.

"They stay with you, like companions. I shared the last few hours of their lives with them … forming a bond that transcends into something almost spiritual even for those that don't believe. Above all else, that is what counts and it remains a privilege."

No comments:

Post a Comment