'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Monday, 11 September 2023

Saturday, 24 December 2022

Sunday, 25 April 2021

Saturday, 24 April 2021

Teacher Cancelled by Eton for Controversial Lecture Speaks Out

Monday, 30 November 2020

Saturday, 17 March 2018

The crisis in modern masculinity

On the evening of 30 January 1948, five months after the independence and partition of India, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was walking to a prayer meeting at his temporary home in New Delhi when he was shot three times, at point-blank range. He collapsed and died instantly. His assassin, originally feared to be Muslim, turned out to be Nathuram Godse, a Hindu Brahmin from western India. Godse, who made no attempt to escape, said in court that he felt compelled to kill Gandhi since the leader with his womanly politics was emasculating the Hindu nation – in particular, with his generosity to Muslims. Godse is a hero today in an India utterly transformed by Hindu chauvinists – an India in which Mein Kampf is a bestseller, a political movement inspired by European fascists dominates politics and culture, and Narendra Modi, a Hindu supremacist accused of mass murder, is prime minister. For all his talk of Hindu genius, Godse flagrantly plagiarised the fictions of European ethnic-racial chauvinists and imperialists. For the first years of his life he was raised as a girl, with a nose ring, and later tried to gain a hard-edged masculine identity through Hindu supremacism. Yet for many struggling young Indians today Godse represents, along with Adolf Hitler, a triumphantly realised individual and national manhood.

The moral prestige of Gandhi’s murderer is only one sign among many of what seems to be a global crisis of masculinity. Luridly retro ideas of what it means to be a strong man have gone mainstream even in so-called advanced nations. In January Jordan B Peterson, a Canadian self-help writer who laments that “the west has lost faith in masculinity” and denounces the “murderous equity doctrine” espoused by women, was hailed in the New York Times as “the most influential public intellectual in the western world right now”.

‘The west has lost faith in masculinity’ … self-help writer Jordan Peterson. Photograph: Carlos Osorio/Toronto Star via Getty Images

This is, hopefully, an exaggeration. It is arguable, however, that a frenetic pursuit of masculinity has characterised public life in the west since 9/11; and it presaged the serial-groping president who boasts of his big penis and nuclear button. “From the ashes of September 11,” the Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan exulted a few weeks after the attack, “arise the manly virtues.” Noonan, who today admires Peterson’s “tough” talk, hailed the re-emergence of “masculine men, men who push things and pull things”, such as George W Bush, who she half expected to “tear open his shirt and reveal the big ‘S’ on his chest”. Such gush, commonplace at the time, helped Bush, who had initially gone missing in action on 11 September, reinvent himself as a dashing commander-in-chief (and grow cocky enough to dress up as a fighter pilot and compliment Tony Blair’s “cojones”).

Amid this rush of testosterone in the Anglo-American establishment, many deskbound journalists fancied themselves as unflinching warriors. “We will,” David Brooks, another of Peterson’s fans, vowed, “destroy innocent villages by accident, shrug our shoulders and continue fighting.”

As manly virtues arose, attacks on women, and feminists in particular, in the west became nearly as fierce as the wars waged abroad to rescue Muslim damsels in distress. In Manliness (2006) Harvey Mansfield, a political philosopher at Harvard, denounced working women for undermining the protective role of men. The historian Niall Ferguson, a self-declared neo-imperialist, bemoaned that “girls no longer play with dolls” and that feminists have forced Europe into demographic decline. More revealingly, the few women publicly critical of the bellicosity, such as Katha Pollitt, Susan Sontag and Arundhati Roy, were “mounted on poles for public whipping” and flogged, Barbara Kingsolver wrote, with “words like bitch and airhead and moron and silly”. At the same time, Vanity Fair’s photo essay on the Bush administration at war commended the president for his masculine sangfroid and hailed his deputy, Dick Cheney, as “The Rock”.

Psychotic masculinity can be seen everywhere from ISIS to mass-murderer Anders Breivik, who claimed Viking ancestry

Some of this post-9/11 cocksmanship was no doubt provoked by Osama bin Laden’s slurs about American manhood: that the free and the brave had gone “soft” and “weak”. Humiliation in Vietnam similarly brought forth such cartoon visions of masculinity as Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger. It is also true that historically privileged men tend to be profoundly disturbed by perceived competition from women, gay people and diverse ethnic and religious groups. In Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the Fin de Siecle (1990) Elaine Showalter described the great terror induced among many men by the very modest gains of feminists in the late 19th century: “fears of regression and degeneration, the longing for strict border controls around the definition of gender, as well as race, class and nationality”.

In the 1950s, historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr was already warning of the “expanding, aggressive force” of women, “seizing new domains like a conquering army”. Exasperated by the “castrated” American male and his “feminine fascination for the downtrodden”, Schlesinger, the original exponent of muscular liberalism, longed for the “frontiersmen” of American history who “were men, and it did not occur to them to think twice about it”.

These majestically male makers of the modern west are being forced to think twice about a lot today. Gay men and women are freer than before to love whom they love, and to marry them. Women expect greater self-fulfilment in the workplace, at home and in bed. Trump may have the biggest nuclear button, but China leads in artificial intelligence as well as old-style mass manufacturing. And technology and automation threaten to render obsolete the men who push and pull things – most damagingly in the west.

Many straight white men feel besieged by “uppity” Chinese and Indian people, by Muslims and feminists, not to mention gay bodybuilders, butch women and trans people. Not surprisingly they are susceptible to Peterson’s notion that the ostensible destruction of “the traditional household division of labour” has led to “chaos”. This fear and insecurity of a male minority has spiralled into a politics of hysteria in the two dominant imperial powers of the modern era. In Britain, the aloof and stiff upper-lipped English gentleman, that epitome of controlled imperial power, has given way to such verbally incontinent Brexiters as Boris Johnson. The rightwing journalist Douglas Murray, among many elegists of English manhood, deplores “emasculated Italians, Europeans and westerners in general” and esteems Trump for “reminding the west of what is great about ourselves”. And, indeed, whether threatening North Korea with nuclear incineration, belittling people with disabilities or groping women, the American president confirms that some winners of modern history will do anything to shore up their sense of entitlement.

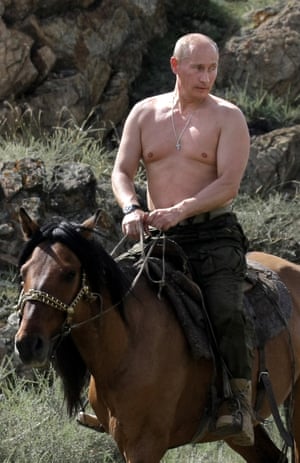

Rear-guard machismo … Vladimir Putin on holiday in southern Siberia in 2009. Photograph: Alexey Druzhinin/AFP/Getty Images

But gaudy displays of brute manliness in the west, and frenzied loathing of what the alt-rightists call “cucks” and “cultural Marxists”, are not merely a reaction to insolent former weaklings. Such manic assertions of hyper-masculinity have recurred in modern history. They have also profoundly shaped politics and culture in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Osama bin Laden believed that Muslims “have been deprived of their manhood” and could recover it by obliterating the phallic symbols of American power. Beheading and raping innocent captives in the name of the caliphate, the black-hooded young volunteers of Islamic State were as obviously a case of psychotic masculinity as the Norwegian mass-murderer Anders Behring Breivik, who claimed Viking warriors as his ancestors. Last month, the Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte told female rebels in his country that “We will not kill you. We will just shoot you in the vagina.” Tormenting hapless minorities, India’s Hindu supremacist chieftains seem obsessed with proving, as one asserted after India’s nuclear tests in 1998, “we are not eunuchs any more”.

Morbid visions of castration and emasculation, civilisational decline and decay, connect Godse and Schlesinger to Bin Laden and Trump, and many other exponents of a rear-guard machismo today. They are susceptible to cliched metaphors of “soft” and “passive” femininity, “hard” and “active” masculinity; they are nostalgic for a time when men did not have to think twice about being men. And whether Hindu chauvinist, radical Islamist or white nationalist, their self-image depends on despising and excluding women. It is as though the fantasy of male strength measures itself most gratifyingly against the fantasy of female weakness. Equating women with impotence and seized by panic about becoming cucks, these rancorously angry men are symptoms of an endemic and seemingly unresolvable crisis of masculinity.

When did this crisis begin? And why does it seem so inescapably global? Writing Age of Anger: A History of the Present, I began to think that a perpetual crisis stalks the modern world. It began in the 19th century, with the most radical shift in human history: the replacement of agrarian and rural societies by a volatile socio-economic order, which, defined by industrial capitalism, came to be rigidly organised through new sexual and racial divisions of labour. And the crisis seems universal today because a web of restrictive gender norms, spun in modernising western Europe and America, has come to cover the remotest corners of the earth as they undergo their own socio-economic revolutions.

There were always many ways of being a man or a woman. Anthropologists and historians of the world’s astonishingly diverse pre-industrial societies have consistently revealed that there is no clear link between biological makeup and behaviour, no connection between masculinity and vigorous men, or femininity and passive women. Indians, British colonialists were disgusted to find, revered belligerent and sexually voracious goddesses, such as Kali; their heroes were flute-playing idlers such as Krishna. A vast Indian literature attests to mutably gendered men and women, elite as well as folk traditions of androgyny and same-sex eroticism.

These unselfconscious traditions began to come under unprecedented assault in the 19th century, when societies constituted by exploitation and exclusion, and stratified along gender and racial lines, emerged as the world’s most powerful; and when such profound shocks of modernity as nation-building, rural-urban migration, imperial expansion and industrialisation drastically changed all modes of human perception. A hierarchy of manly and unmanly human beings had long existed in many societies without being central in them. During the 19th century, it came to be universally imposed, with men and women straitjacketed into specific roles.

‘In the 19th century, the ideal of a strong, fearless manhood came to be embodied in muscular selves, nations, empires and races’

The modern west appears, in the western supremacist version of history, as the guarantor of equality and liberty to all. In actuality, a notion of gender (and racial) inequality, grounded in biological difference, was, as Joan Wallach Scott demonstrates in her recent book Sex and Secularism, nothing less than “the social foundation of modern western nation-states”. Immanuel Kant dismissed women as incapable of practical reason, individual autonomy, objectivity, courage and strength. Napoleon, the child of the French Revolution and the Enlightenment, believed women ought to stay at home and procreate; his Napoleonic Code, which inspired state laws across the world, notoriously subordinated women to their fathers and husbands. Thomas Jefferson, America’s founding father, commended women, “who have the good sense to value domestic happiness above all other” and who are “too wise to wrinkle their foreheads with politics”. Such prejudices helped replace traditional patriarchy with the exclusionary ideals of masculinity as the modern world came into being.

On such grounds, women were denied political participation and forced into subordinate roles in the family and the labour market. Pop psychologists periodically insist that men are from Mars and women from Venus, lamenting the loss of what Peterson calls “traditional” divisions of labour, without acknowledging that capitalist, industrial and expansionist societies required a fresh division of labour, or that the straight white men who supervised them deemed women unfit, due to their physical or intellectual inferiority, to undertake territorial aggrandisement, nation-building, industrial production, international trade, and scientific innovation. Women’s bodies were meant to reproduce and safeguard the future of the family, race and nation; men’s were supposed to labour and fight. To be a “mature” man was to adjust oneself to society and fulfil one’s responsibility as breadwinner, father and soldier. “When men fear work or fear righteous war,” as Theodore Roosevelt put it, “when women fear motherhood, they tremble on the brink of doom.” As the 19th century progressed, many such cultural assumptions about male and female identity morphed into timeless truths. They are, as Peterson’s rowdy fan club reveals, more vigorously upheld today than the “truths” of racial inequality, which were also simultaneously grounded in “nature”, or pseudo-biology.

Scott points out that the modes of sexual difference defined in the modernising west actually helped secure, “the racial superiority of western nations to their ‘others’ – in Africa, Asia, and Latin America”. “White skin was associated with ‘normal’ gender systems, dark skin with immaturity and perversity.” Thus, the British judged their Kali-worshipping Indian subjects to be an unmanly and childish people who ought not to wrinkle their foreheads with ideas of self-rule. The Chinese were widely seen, including in western Chinatowns, as pigtailed cowards. Even Muslims, Christendom’s formidable old rivals, came to be derided as pitiably “feminine” during the high noon of imperialism.

Gandhi explicitly subverted these gendered prejudices of European imperialists (and their Hindu imitators): that femininity was the absence of masculinity. Rejecting the western identification of rulers with male supremacy and subjecthood with feminine submissiveness, he offered an activist politics based on rigorous self-examination and maternal tenderness. This rejection eventually cost him his life. But he could see how much the male will to power was fed by a fantasy of the female other as a regressive being – someone to be subdued and dominated – and how much this pathology had infected modern politics and culture.

As Hindu nationalisation got into gear, formerly chubby Bollywood stars began to flaunt bulging biceps

Its most insidious expression was the conquest and exploitation of people deemed feminine, and, therefore, less than human – a violence that became normalised in the 19th century. For many Europeans and Americans, to be a true man was to be an ardent imperialist and nationalist. Even so clear-sighted a figure as Alexis de Tocqueville longed for his French male compatriots to realise their “warlike” and “virile” nature in crushing Arabs in north Africa, leaving women to deal with the petty concerns of domestic life.

As the century progressed, the quest for virility distilled a widespread response among men psychically battered by such uncontrollable and emasculating phenomena as industrialisation, urbanisation and mechanisation. The ideal of a strong, fearless manhood came to be embodied in muscular selves, nations, empires and races. Living up to this daunting ideal required eradicating all traces of feminine timidity and childishness. Failure incited self-loathing – and a craving for regenerative violence. Mocked with such unmanly epithets as “weakling” and “Oscar Wilde”, Roosevelt tried to overcome, Gore Vidal once pointed out, “his physical fragility through ‘manly’ activities of which the most exciting and ennobling was war”. It is no coincidence that the loathing of homosexuals, and the hunt for sacrificial victims such as Wilde, was never more vicious and organized than during this most intense phase of European imperialism.

One image came to be central to all attempts to recuperate the lost manhood of self and nation: the invincible body, represented in our own age of extremes by steroid-juiced, knobbly musculature. Actually, size matters today much less than it ever did; not many muscles are required for increasingly sedentary work habits and lifestyles. Nevertheless, an obsession with raw brawn and sheer mass still shapes political cultures. Trump’s boasts about the size of his body parts were preceded by Vladimir Putin’s displays of his pectorals – advertisements for a Russia re-masculinised after its emasculation by Boris Yeltsin, a flabby drunk. But shirtless hunks are also a striking recent phenomenon in Godse’s “rising” India. In the 90s, just as India’s Hindu nationalisation got into gear, formerly scrawny or chubby Bollywood stars began to flaunt glisteningly hard abs and bulging biceps; Rama, the lean-limbed hero of the Ramayana, started to resemble Rambo in calendar art and political posters. These buffed-up bodies of popular culture foreshadowed Modi, who rose to power boasting of his 56-inch chest, and promising true national potency to young unemployed stragglers.

This vengeful masculinist nationalism was the original creation of Germans in the early 19th century, who first outlined a vision of creating a superbly fit people or master race and fervently embraced such typically modern forms of physical exercise as gymnastics, callisthenics and yoga and fads like nudism. But pumped-up anatomy emerged as a “natural” embodiment of the evidently exclusive male virtue of strength only as the century ended. As societies across the west became more industrial, urban and bureaucratic, property-owning farmers and self-employed artisans rapidly turned into faceless office workers and professionals. With “rational calculation” installed as the new deity, “each man”, Max Weber warned in 1909, “becomes a little cog in the machine”, pathetically obsessed with becoming “a bigger cog”. Increasingly deprived of their old skills and autonomy in the iron cage of modernity, working class men tried to secure their dignity by embodying it in bulky brawn.

India’s prime minister Narendra Modi rose to power boasting of his 56-inch chest, and promising true national potency. Photograph: Danish Ismail/Reuters

Historians have emphasised how male workers, humiliated by such repressive industrial practices as automation and time management, also began to assert their manhood by swearing, drinking and sexually harassing the few women in the workforce – the beginning of an aggressive hardhat culture that has reached deep into blue-collar workplaces during the decades-long reign of neoliberalism. Towards the end of the 19th century large numbers of men embraced sports and physical fitness, and launched fan clubs of pugnacious footballers and boxers.

It wasn’t just working men. Upper-class parents in America and Britain had begun to send their sons to boarding schools in the hope that their bodies and moral characters would be suitably toughened up in the absence of corrupting feminine influences. Competitive sports, which were first organised in the second half of the 19th century, became a much-favoured means of pre-empting sissiness – and of mass-producing virile imperialists. It was widely believed that putative empire-builders would be too exhausted by their exertions on the playing fields of Eton and Harrow to masturbate.

But masculinity, a dream of power, tends to get more elusive the more intensely it is pursued; and the dread of emasculation by opaque economic, political and social forces continued to deepen. It drove many fin de siècle writers as well as politicians in Europe and the US into hyper-masculine trances of racial nationalism – and, eventually, the calamity of the first world war. Nations and races as well as individuals were conceptualised as biological entities, which could be honed into unassailable organisms. Fear of “race suicide”, cults of physical education and daydreams of a “New Man” went global, along with strictures against masturbation, as the inflexible modern ideology of gender difference reached non-western societies.

European colonialists went on to impose laws that enshrined their virulent homophobia and promoted heterosexual conjugality and patrilineal orders. Their prejudices were also entrenched outside the west by the victims of what the Indian critic Ashis Nandy calls “internal colonialism”: those subjects of European empires who pleaded guilty to the accusation that they were effeminate, and who decided to man up in order to catch up with their white overlords.

This accounts for a startling and still little explored phenomenon: how men within all major religious communities – Buddhist, Hindu and Jewish as well as Christian and Islamic – started in the late 19th century to simultaneously bemoan their lost virility and urge the creation of hard, inviolable bodies, whether of individual men, the nation or the umma. These included early Zionists (Max Nordau, who dreamed of Muskeljudentum, “Jewry of Muscle”), Asian anti-imperialists (Swami Vivekananda, Modi’s hero, who exhorted Hindus to build “biceps”, and Anagarika Dharmapala, who helped develop the muscular Buddhism being horribly flexed by Myanmar’s ethnic-cleansers these days) as well as fanatical imperialists such as Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Scout movement.

The most lethal consequences of this mimic machismo unfolded in the first decades of the 20th century. “Never before and never afterwards”, as historian George Mosse, the pioneering historian of masculinity, wrote, “has masculinity been elevated to such heights as during fascism”. Mussolini, like Roosevelt, transformed himself from a sissy into a fire-breathing imperialist. “The weak must be hammered away,” declared Hitler, another physically ill-favoured fascist. Such wannabe members of the Aryan master race accordingly defined themselves against the cowardly Jew and discovered themselves as men of steel in acts of mass murder.

This hunt for manliness continues to contaminate politics and culture across the world in the 21st century. Rapid economic, social and technological change in our own time has plunged an exponentially larger number of uprooted and bewildered men into a doomed quest for masculine certainties. The scope for old-style imperialist aggrandisement and forging a master race may have diminished. But there are, in the age of neoliberal individualism, infinitely more unrealised claims to masculine identity in grotesquely unequal societies around the world. Myths of the self-made man have forced men everywhere into a relentless and often futile hunt for individual power and wealth, in which they imagine women and members of minorities as competitors. Many more men try to degrade and exclude women in their attempt to show some mastery that is supposed to inhere in their biological nature.

Fear of feminizsation has driven demagogic movements like that unleashed by the locker room bully in the White House

Frustration and fear of feminisation have helped boost demagogic movements similar to the one unleashed by the locker room bully in the White House. Godse’s hyper-masculine cliches have vanquished the traditions of androgyny that Gandhi upheld – and not just in India. Young Pakistani men revere the playboy-turned-politician Imran Khan as their alpha male redeemer; they turn viciously on critics of his indiscretions. Similarly embodying a triumphant masculinity in the eyes of his followers, the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan can do no wrong. Rodrigo Duterte jokes, with brazen frequency, about rape.

Misogyny now flourishes in the public sphere because, as in modernising Europe and America, many toilers daydream of a primordial past when real men were on top, and women knew their place. Loathing of “liberated” women who seem to be usurping male domains is evident not only on social media but also in brutal physical assaults. These are sanctioned by pseudo-traditional ideologies such as Hindu supremacism and Islamic fundamentalism that offer to many thwarted men in Asia and Africa a redeeming machismo: the gratifying replacement of neoliberalism’s bogus promise of equal opportunity with old-style patriarchy.

Susan Faludi argues that many Americans used the 9/11 attacks to shrink the gains of feminism and push women back into passive roles. Peterson’s traditionalism is the latest of many attempts in the west in recent years to restore the authority of men, or to remasculinise society. These include the deployment of “shock-and-awe” violence, loathing of cucks, cultural Marxists and feminists, re-imagining a silver-spooned posturer like Bush as superman, and, finally, the political apotheosis of a serial groper.

This recurrent search for security in coarse manhood confirms that the history of modern masculinity is the history of a fantasy. It describes the doomed quest for a stable and ordered world that entails nothing less than war on the irrepressible plurality of human existence – a war that is periodically renewed despite its devastating failures. An outlandish phobia of women and effeminacy may be hardwired into the long social, political and cultural dominance of men. It could be that their wounded sense of entitlement, or resentment over being denied their customary claim to power and privilege, will continue to make many men vulnerable to such vendors of faux masculinity as Trump and Modi. A compassionate analysis of their rage and despair, however, would conclude that men are as much imprisoned by man-made gender norms as women.

“One is not born, but rather becomes a woman” wrote Simone de Beauvoir. She might as well have said the same for men. “It is civilisation as a whole that produces such a creature.” And forces him into a ruinous pursuit of power. Compared with women, men are almost everywhere more exposed to alcoholism, drug addiction, serious accidents and cardiovascular disease; they have significantly lower life expectancies and are more likely to kill themselves. The first victims of the quest for a mythical male potency are arguably men themselves, whether in school playgrounds, offices, prisons or battlefields. This everyday experience of fear and trauma binds them to women in more ways than most men, trapped by myths of resolute manhood, tend to acknowledge.

Certainly, men would waste this latest crisis of masculinity if they deny or underplay the experience of vulnerability they share with women on a planet that is itself endangered. Masculine power will always remain maddeningly elusive, prone to periodic crises, breakdowns and panicky reassertions. It is an unfulfillable ideal, a hallucination of command and control, and an illusion of mastery, in a world where all that is solid melts into thin air, and where even the ostensibly powerful are haunted by the spectre of loss and displacement. As a straitjacket of onerous roles and impossible expectations, masculinity has become a source of great suffering – for men as much as women. To understand this is not only to grasp its global crisis today. It is also to sight one possibility of resolving the crisis: a release from the absurd but crippling fear that one has not been man enough.

Sunday, 28 January 2018

Is single the new black?

Last evening, I went out with my college friend to a popular coffee shop in Kolkata, crowded with young lovers bedecked in the colours of Saraswati Puja, a festival that heralds the beginning of spring.

At the table beside us sat a couple who looked like typical millennials — they constantly clicked indulgent selfies, pouted non-stop, uploaded everything online immediately, with the boy checking and declaring the number of Likes triumphantly by thumping on the table.

‘Young love… wait till they are married and saddled with kids, pets, maids, homework and in-laws,’ my friend smirked.

Feminist type

‘We’ll be told we are eavesdropping, bad manners,’ I winked. My friend was about to say something when the girl at the table, who wore a purple sari and backless choli, raised her voice.

We stole a fleeting glance.

‘Let me tell you straight… I have no interest in being married. I am extremely independent, love my job, enjoy solo travel, I can’t give up my flat… and anyway, I am… umm… commitment phobic…’ She made a face and pushed away the boy’s left hand.

Was there a ring in there?

My friend and I exchanged looks.

‘Dude,’ the boy sniggered, taking back his arm defensively, adding almost under his breath, ‘You don’t want to grow into a sexless spinster, living alone with a bunch of cats in a cold, lonely apartment at 40.’

I’d just turned 40 in December, on the 14th. The last word stuck to me, more than the rest of his bhavishyawani.

I waited for the girl’s response.

‘Besides, I don’t think you are commitment phobic, you’ve had a string of flings, haven’t you?’ the boy clicked his tongue, resuming sheepishly, ‘I would say you are nothing but a bloody feminist.’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’ the girl retorted in a shrill octave.

The boy asked for the bill.

‘Nothing,’ he shrugged his shoulders.

‘No, tell me,’ the girl met his eyes.

‘It means that you hate men… that you think you are better and can survive alone. It means that you are too opinionated and have a foot-in-mouth disease. It means you want multiple partners, and maybe you are a lesbian. It means you have jholawala, nari morcha type principles… it means you are lonely, lousy and lost…’

* * * *

Single women reportedly constitute 21% of India’s female population, being close to 73 million in number. These include unmarried, divorced, separated and widowed women. Between 2001 and 2011, there was an almost 40% increase in their numbers. Media reports say that the Women and Child Development ministry under Maneka Gandhi is slated to revise policy for the first time since 2001 to address the concerns around being single and female, which include social isolation and difficulties in accessing even ordinary services. .

There’s been a huge growth in this demographic, and ministry officials have said that government policy must prepare for this evolution by empowering single women through skills development and economic incentives.

The policy revision also aims to address concerns related to widows and universal health benefits for all women. And yet, a little over a year ago, and despite the social relevance of the subject, when I actually discussed the idea of a non-fiction book on single women in my circle of single women friends, I sensed a reluctance to talk freely about what being single really meant in India.

Some of them, 40-plus, shyly confessed that they’ve just created their nth profile on a matrimonial site, but made me swear I would not tell anyone else lest they be laughed at. Others clandestinely admitted to flings with married or younger men.

They spoke of serious struggles with basic life issues such as getting a flat on rent or being taken seriously as a start-up entrepreneur or getting a business loan or even getting an abortion (statistics collated by Mumbai’s International Institute for Population Sciences claim that 76% of the women who come for first-time abortions are single).

They confessed to a gnawing sense of loneliness, the looming anxiety about the onset of old age, health issues, of losing parents, siblings and friends over time, of personal security, of being elderly and alone.

I started introspecting on my own single life. When did I begin to realise it wasn’t so much a choice as a culmination of circumstances that I must eventually get used to and learn to adapt to, despite the occasional speed-breaks. That being single wasn’t only about relationship-centric fears.

It also covered physical and mental health, living with parents vis-a-vis alone in another city, the nauseating, never-ending pressure of marriage, the need for sex (a friend insists on calling it ‘internal servicing’), the desire to birth one’s own children, coupled with a general all-consuming pressure to conform to the larger majority, the statistic that sells — married people — who seem to be swallowing you up and swarming in population, be it virtually or really.

* * * *

‘Get her uterus removed,’ the gynaecologist declared. It was three years ago and I was at one of Delhi’s prestigious hospitals. She was the third gynaec I was consulting. I kept going back to her every Wednesday at 4 p.m., waiting on the claustrophobic ground floor, complaining of how my menstrual pain had gotten severe in the last few cycles, even unbearable. My mother accompanied me on most occasions, vouching for me, a lingering sadness in her ageing eyes. Perhaps she was just as fragile. In ways that we could never show each other.

‘But she’s so young, only in her 30s?’ my mother stuttered, protesting, as if against a looming death warrant. The doctor was busy talking with the nurse about a woman in labour. Not very interested in the ones who didn’t qualify in her estimation. Those like me who kept coming back — same complaint, same pain, same marital status.

“Why don’t you find her a husband soon? With her history… first Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome… now endometriosis…and, of course, her weight… is she interested in having a baby anyway?” I pushed my chair back impatiently, fighting back tears.

‘Shall we try Ananda Bazaar? They have a ‘Cosmopolitan’ section… more your type,’ Ma had whispered on our way back, as I looked away.

Beleaguered. Belittled. Barren?

* * * *

Nita Mathur (name changed on request) was born in a conservative Uttar Pradesh family, and grew up watching her mother ostracised for not bearing a son. I met the 34-year-old HR professional in an upscale South Delhi café a month before her marriage, which had been arranged by a family astrologer. Nita was preparing to return to Kanpur, her hometown. ‘I grew up with a gnawing guilt that I was born a girl… I wanted to get out of Kanpur at any cost. I battled with my father and uncles to come to Delhi to get an MBA degree,” she told me.

Like a virgin

For Nita, living alone in a Delhi PG meant life on her own terms, earning her way. She started dating, had sex. “It was, strangely, a way to get back at the closeted patriarchy I had been forced to deal with as a girl,” she said.

But her single status and living alone was a stigma for her parents, who wanted Nita married, and her sisters after her. They pressurised her, using tears and threats. “My mother always cried on the phone, warning me that life as a single woman, though seemingly attractive, would return to haunt me later. She told me my behaviour would affect my sisters’ lives….”

Nita finally agreed to marry. And since she could not tell anyone that she was sexually active, she decided to have a hymen reconstruction surgery. “It was the first question my to-be groom asked when we were granted half an hour alone.” Nita spent ₹60,000 on the half-hour procedure.

In an April 2015 report in indiatimes.com, Dr. Anup Dhir, a cosmetologist from Apollo Hospital, said, ‘There’s been an increase of 20-30% in these surgeries annually. The majority of women who opt for this surgery are in the 20 to 30 age group.’

* * * *

I went to visit a single friend in her 40s who lives in a plush apartment complex in Thane. As my rented car entered the imposing iron gates, a lady security officer asked which apartment I was visiting. When I told her my friend’s name and flat number, she smirked: ‘Oh, the madam who lives by herself? Akeli? Not married?’

In the course of my interviews with 3,000 single urban women across India whose voices are integral to breaking the stigmatised silence around singlehood, I came across Shikha Makan, whose documentary Bachelor Girls is on the same subject.

Shikha spoke of being in the advertising industry, of keeping late hours. “From the first day, we felt uncomfortable. The watchman stared at us, as if he wanted to find out what we were up to.” Once, when she returned home at 2 a.m., a male colleague escorted her home. But when they reached the gate, the watchman stopped them and called the society chairman who accused Shikha of running a brothel. He threatened to throw her out.

“I called my father, who gave him a piece of his mind, and we continued to stay there. But we felt extremely uncomfortable. Then, the harassment started; someone would ring our bell at 3 a.m. or write nasty stuff on the walls. We decided to leave.”

* * * *

Ruchhita Kazaria, 35 and single, born to a Marwari family, started her own advertising agency, Arcee Enterprises, in 2004. She has since faced backlash for trying to conduct business without the backing of a husband’s surname or the validation of a male partner. Running her own company for the past 12 years has led to Ruchhita believing that “women in general, unfortunately, are still predominantly perceived as designers, back-office assistants, PR coordinators, anything but the founder-owner of a business entity.”

Sans arm candy

“In October 2014, a friend asked if I was “secretly” dating someone, probably finding it difficult to digest that a single woman could head a company minus a male counterpart and socialise sans arm candy,” she wrote to me. Within 15 minutes, the friend had sought to enrol Ruchhita with couples and groups that participated in swapping, threesomes and orgies, encouraging her to be a part of this ‘discreet’ group, to ‘hang loose’.

With single women, it’s their sexuality that’s always at the forefront of social exchanges, not their minds or talents.

* * * *

‘What did you say?’ the girl at the next table squeals, her eyes glinting.

The boy’s chest heaves as she shoves in the returned change into his shirt pocket.

‘I am a feminist,’ I say, suddenly, protectively.

Then before the boy can say something, I add, ‘and I am single, 40. So?’

The girl pushes her chair back.

‘I’m Payal,’ she swallows hard.

‘I’m Riya, 54, divorced, two kids, that’s my son,’ the lady sitting behind them walks over to the girl’s table.

‘Amio single, feminist, war widow,’ says another woman who has just walked in. ‘Can I have your table please after you leave? Bad knees!’

The boy looks genuinely puzzled.

‘I hate cats. But I love sex,’ my friend pipes up.

We burst out laughing.

‘Single, huh?’ the boy barks.

‘No, but my husband is away on work in another city, so maybe, umm, okay, just feminist,’ she grits her teeth.

Five of us then make a curious semi-circle. Standing around the girl, who wraps her hands around her shoulders.

We watch him stomp off and leave. The girl looks at me. I hold my friend’s hand. The older lady touches my back. The woman waiting for the table clumsily clicks a selfie.

And just like that, in the middle of an ordinary, noisy restaurant, we become the same. A statistic. A story.

Sunday, 27 March 2016

The Economist's Concubine

In recent decades, economics has been colonizing the study of human activities hitherto considered exempt from formal calculus. What critics call “economics imperialism” has given rise to an economics of love, of art, of music, of language, of literature, and of much else.

The unifying idea underlying this extension of economics is that whatever people do, whether it is making love or making widgets, they aim to achieve the best results at the least cost. These benefits and costs can be reduced to money. So people are always looking for the best financial return on their transactions.

This is contrary to the popular separation of activities in which it is right (and rational) to count the cost, and those in which people do not (and should not) count the cost. To say that affairs of the heart are subject to cold calculation is, say the critics, to miss the point. But cold-hearted calculation, reply the economists, is exactly the point.

The pioneer of the economic approach to love was the Nobel laureate Gary Becker, who spent most of his career at the University of Chicago (where else?). In his seminal paper, “A Theory of Marriage,” published in 1973, Becker argued that selecting a partner is its own kind of market, and marriages occur only when both partners gain. It’s a very sophisticated theory, relying on the complementary nature of male and female work, but which tends to treat love as a cost-reducing mechanism.

More recently, economists such as Columbia University’s Lena Edlund and University of Marburg’s Evelyn Korn, as well as Marina Della Giusta of Reading University, Maria Laura di Tommaso of the University of Turin, and Steiner Strøm of the University of Oslo, have applied the same approach to prostitution. Here, the economic approach might seem to work better, given that money is, admittedly, the only relevant currency. Edlund and Korn treat wives and prostitutes as substitutes. A third alternative, working in a regular job, is ruled out by assumption.

According to the data, prostitutes make a lot more money than women working in ordinary jobs. So the question is: why is there such a high premium for such low skills?

On the demand side is the randy male, often in transit, who weighs the benefits of going with prostitutes against the costs of getting caught. On the supply side the prostitute will require higher earnings to compensate for her higher risk of disease, violence, and blighted marriage prospects. “If marriage is a source of income for women,” write Edlund and Korn “then the prostitute has to be compensated for foregone marriage market opportunities.” So the premium reflects the opportunity cost to the prostitute of performing sex work.

There is a ready answer to the question of why competition does not drive down sex workers’ rewards. They have a “reservation wage”: If they are offered less, they will choose a less risky line of work.

What warrant does the state have to interfere with the contracts that are struck within this market of willing buyers and sellers? Why not decriminalize the market altogether, as many sex workers want? Like all markets, the sex market needs regulation, particularly to protect the health and safety of its workers. And, as in all markets, criminal activity, including violence, is already illegal.

But on the other side, there is a strong movement to ban buying sex altogether. The so-called Sex Buyer Law, criminalizing the purchase, though not the sale, of sexual services has been implemented in Sweden, Norway, Iceland, and Northern Ireland. The enforced reduction of demand is expected to reduce supply, without the need to criminalize the supplier. There is some evidence that it has had the intended effect. (Though supporters of the so-called Nordic System ignore the effect of criminalizing the purchase of sex on the earnings of those who supply it, or would have supplied it.)

The movement to ban buying sex has been strengthened by the growth of international trafficking in women (as well as drugs). This may be counted as a cost of globalization, especially when it involves an influx into the West from countries where attitudes toward women are very different.

But the proposed remedy is too extreme. The premise of the Sex Buyer Law is that prostitution is always involuntary for women – that it is an organic form of violence against women and girls. But I see no reason to believe this. The key question concerns the definition of the word “voluntary.”

True, some prostitutes are enslaved, and the men who use their services should be prosecuted. But there are already laws on the books against the use of slave labor. I would guess that most prostitutes have chosen their work reluctantly, under pressure of need, not involuntarily. If men who use their services are criminalized, then so should people who use the services of supermarket checkout employees, call-center workers, and so on.

Then there are some prostitutes (a minority, to be sure) who claim to enjoy their work. And, of course, there are male prostitutes, gay and straight, who are typically ignored by feminist critics of prostitution. In short, the view of human nature of those who seek to ban the purchase of sex is as constricted as that of the economists. As St. Augustine put it, “If you do away with harlots, the world will be convulsed with lust.”

Ultimately, all arguments against prostitution based on notions of inequality and coercion are superficial. There is, of course, a strong ethical argument against prostitution. But unless we are prepared to engage with that – and our liberal civilization is not – the best we can do is to regulate the trade.

Tuesday, 22 March 2016

Monday, 14 March 2016

Lecture on Nationalism at JNU #5 - Nivedita Menon

This attack on Nivedita Menon

First and foremost, feminism in India, going back to the nineteenth century, has never had the luxury to simply be about women. This is because the struggles over women’s wrongs and rights in the Indian context have always been tied to larger issues — to the histories of colonialism and nationalism before Independence; to the meanings of development after 1947; and to the conflicts over democracy today. Feminists have been demonstrating how the hierarchies of gender in India are intertwined with those of caste; how the promises of national development remained unfulfilled for the vast majority of women; and how families have often turned into sites of the worst violence against their very own women.

That is precisely why we are outraged not by the fact that people disagree with Prof. Menon or want to question her views, but by the mode in which they are choosing to do so. The malicious campaign we have witnessed in recent days is not about expressing dissent; it is about bullying and intimidation. It reveals a deeply undemocratic mindset that offers no arguments of its own, but tries to capture public attention by repeated, sensationalised attacks that work by twisting statements and taking them out of their context. What is truly worrisome is that it does not just stop at this; this campaign goes far beyond the limits of public debate to make opponents fear for their lives by whipping up a frenzy and creating a situation where the laws of the land are seen as irrelevant. These are acts of cowardice, not bravery, least of all acts of heroism in the service of Mother India.

Monday, 29 February 2016

How have the British Muslim men involved in the Rotherham child sex grooming gang been treating their own wives?

The Pakistani Muslim men – three brothers and an uncle – who groomed, raped and destroyed young girls in Rotherham have been given long sentences. Two local white women have also been convicted of supplying girls to the men. The reactions to these verdicts are instructive. Racists are red with righteous rage; this is what happens, they say, when you let “coloureds” into the country. Many anti-racists, just as blindly furious, assert race and ethnicity have nothing to do with what happened. The white female procurers are their alibis. The rapists’ relatives and community leaders stand by their men. They believe the blokes took what was freely offered by trashy females – children, daughters. Muslims who condemn the exploitation, in their eyes, bring shame on the community. That’s how twisted their values are.

The one question nobody asks is how these men have been treating their sisters and wives. Most of them behave just as abominably and cruelly indoors as they do outside when they prey on young flesh. They want control; they abjure equality. Some – a small minority – do feel a kind of love for the women and girls in the family but many have monstrous views on sexual equality and feminine desire. Home is a cage in which no pleasures are permitted, where hopes and freedoms expire. Activists have sought to free these women for decades. The terrible truth is that as society becomes more permissive, the number of caged birds increases. One caveat: I am not saying all Muslim girls and women are oppressed. What I am saying is that sexual predators from traditional Pakistani families and many other minority communities think all women and girls are low-life. I was looking at my wedding pictures the other day. On a cold, snowy December day, in 2000, I married my English husband in Ealing Town Hall. On the steps we had photos taken. It was freezing cold but I was in a silk sari, as was my mum. My Asian friends in their finery were shivering and smiling happily. The most striking, gorgeous person in the crowd was Humera (not her real name), who had stayed with me several times over the previous two years. She was from a northern town and had escaped a forced marriage. Her family had made her marry a man from Pakistan who had then raped her nightly for months. A social worker helped her escape. I heard of her case and offered to have her live with us for a while. The bruises on her thighs and breasts took months to heal.

She was one of countless such victims, all hidden and hopeless. Forced marriage has since been outlawed and girls have some protection and awareness of their rights but now we have Sharia courts in this country, which condone wife beating, marital rape, compulsory or child marriages, polygamy, paternal ownership of children and extreme sexism. Pre-pubescent Muslim girls are married on Skype. Imams praise this technology, which allows families to trade in their daughters – girls between the ages of six and nine among them. How did our rulers let this happen?

Political scientist Elham Manea, herself a Muslim, has written a new book, Women and Shari’a Law: the Impact of Legal Pluralism in the UK. She investigated 80 faith “councils”, which settle disputes and make quasi-legal decisions. According to Manea these courts are more hardline even than in Pakistan and many of their religious leaders issue horrendous advice. For example, a senior cleric in a British Sharia council pronounced that there was no “right age” for a girl to marry: “As you know, the earlier the better”. Humera’s family were not given religious authorisation to do what they did to her. Imams in the 1990s were conservative but not inflexible Islamicists. Today the human-rights abuses are validated by dozens of Muslim leaders as well as by influential Islamic institutions. Though forced marriages are a curse in Hindu and Sikh families too, they do not have systemised, pervasive doctrines to back their heinous behaviours.

Why is this even important when we are discussing the Rochdale crimes against white British children? Am I trying to deflect attention from those horrors? On the contrary; I am making vital connections. We should find out how those close to the three brothers and the uncle were treated. Was terrible violence meted out to them, too? Should we not know that? More than 1,400 vulnerable white children were abused in Rotherham. Thousands of others are being discovered in other towns. The numbers would shoot up if we also counted the family victims of the groomers.

Grooming and domestic rape often go together. Police and journalists need to be as concerned about the latter as they now (thankfully) are about the former. Families and communities will resist such probes, lob accusations of racism and “insensitivity”. But it has to happen. Females of all backgrounds should be protected from sexual savagery and misogynist Sharia courts. There must be one law for all.

Tuesday, 19 August 2014

10 funniest jokes from the Edinburgh festival fringe 2014

Saturday, 3 February 2007

WHEN OPIUM CAN BE BENIGN

Feb 1st 2007

China's Communist Party, reconsidering Marx's words, is starting to

wonder whether there might not be a use for religion after all

"DEVELOP the dragon spirit; establish a dragon culture," urge large

green characters at the high school in Hongliutan, a poor village at

the foot of a range of bleak loess hills. Though dragon can be a

synonym for China, it is a god known as the Black Dragon that is being

invoked here. Without funds from the Black Dragon's hillside temple, in

a gully behind the village, the school would not exist. Nor, most

likely, would the adjacent primary school and the irrigation system

that brings water from the nearby Wuding River to the village's maize

and cabbage fields.

Many local governments in rural China are mired in debt. Recent central

government efforts to keep peasants happy by abolishing centuries-old

taxes have not made life any easier for these bureaucracies. With their

revenues cut, rural authorities have found it ever more difficult to

scrape together money for health care and education. So they are only

too happy to allow others to share the burden of providing these

services--even the Black Dragon, whose 500-year-old temple was

demolished by Maoist radicals during the Cultural Revolution in the

1960s. Now officials in Yulin, the prefecture to which Hongliutan

belongs, give the temple their blessing.

The revival of the Black Dragon Temple's fortunes is part of a

resurgence of religious or quasi-religious activity across China

that--notwithstanding occasional crackdowns--is transforming the social

and political landscape of many parts of the countryside. Religion is

also attracting many people in the cities, where the party's atheist

ideology has traditionally held stronger sway.

The resurgence encompasses ancient folk religions and ancestor worship,

along with the organised religions of Buddhism, Taoism, Islam (among

ethnic minorities) and, most strikingly, given its foreign origins and

relatively short history in China, Christianity. In the face of this

onslaught, the party is beginning to rethink its approach to religion.

It now acknowledges that it may even have its uses.

In Hongliutan the party appears in retreat. It is not the party

secretary Zhang Tieniu who holds sway. Mr Zhang was the youngest party

chief in the prefecture when he was appointed last year at the age of

32. But in a culture that reveres age, some villagers refer to him

dismissively as a "lad". The man in charge in Hongliutan is 64-year-old

Wang Kehua. Mr Wang happens to belong to the village's main clan. He is

also the village's elected chief (a post which in most villages is

subordinate to that of party secretary). More to the point, he controls

the temple and its money.

It was Mr Wang's idea to rebuild the temple in 1986, a decade after

Mao's death. Mr Wang, who had become one of the village's wealthiest

men by wheeling and dealing elsewhere, donated some of his own money

and organised villagers to add theirs. It was a promising venture.

Historically, the Black Dragon Temple had a reputation extending far

beyond the village. The dragon was renowned in the parched semi-desert

of the north of Shaanxi Province, 600 kilometres (370 miles) west of

Beijing, as a bringer of rain. If the temple was rebuilt, people would

come, pray to the dragon--and spend money.

Mr Wang does not, however, speak of commercial motives. In the bare

concrete-walled room he calls his office, he describes how, one after

the other, the half-dozen villagers who had destroyed the temple in the

1960s fell victim to the vengeful dragon in subsequent years. The man

who had broken off the head of the Black Dragon's effigy (the god is

worshipped in a human-looking form, as shown in the picture above) had

his head blown off when a factory boiler exploded. Another bled to

death after accidentally chopping his foot with an axe. One was crushed

by a donkey cart. Their offspring also suffered ill fate. These events,

says Mr Wang, convinced him of the power of the dragon and of the

importance of reviving its worship.

The temple has no clergy. Visitors are mainly drawn by their belief in

the dragon's power to tell the future. Many want to know whether

business ventures or marriages will succeed. Mr Wang asked the Black

Dragon whether the divinity approved his appointment as temple chief.

It did. The dragon's responses are given in the form of obscurely

worded classical poems written on pieces of paper issued by a

70-year-old villager, Chen Yushan, clad in his blue padded Mao suit. Mr

Chen offers his interpretation of what these poems mean. An

entrepreneur who is told his business will be successful, and who then

enjoys financial success, is quite likely to make a big donation to the

temple.

TURNING A BLIND EYE

Officially, the party regards folk religion as superstition, the public

practice of which is illegal. But in many rural areas officials now

bend the rules. In Yulin prefecture, with 3.4m people, there are 106

officially registered places of worship and many more that are not

officially sanctioned. Most are not part of the five mainstream

religions (China regards the two Christian traditions, Catholicism and

Protestantism, as separate) that the party recognises. But Yulin has

allowed the Black Dragon Temple to affiliate itself with the

government-sponsored Taoist Association. This gives it a cloak of

legitimacy. So too does an arboretum that Mr Wang has planted with

temple funds (at the dragon's request, he says, but it also helps him

show officials how the village is contributing to government efforts to

stop the desert encroaching).

Local officials themselves benefit from the greater tolerance. For all

the party's dictatorial ways, government officers are often fearful of

triggering unrest by enforcing unpopular policies that are not all that

vital to the party's interests (hence the increasingly patchy

implementation of population control). Demonstrations in an official's

jurisdiction can do far more damage to his career than turning a blind

eye to popular religion--so long as such activity does not directly

challenge the party.

There are also more tangible rewards. In his book "Miraculous

Response", Adam Yuet Chau of the School of Oriental and African Studies

in London says that temples applying for official registration

typically have to treat local officials to banquets. Officials, he

adds, support temples that pay them respect and tribute. They also gain

financially from taxes levied on merchants who do business at temple

fairs. Policemen invited to maintain order at these occasions are paid

with cash, good food and liquor.

In the view of local officials, Mr Chau argues, temples play the same

kind of role as commercial enterprises. They generate prosperity for

the local economy and income for the local government. This is

especially true of the Black Dragon Temple, which says it attracts

200,000 people to its ten-day summer fair (the Black Dragon himself,

villagers say, has also shown up in the form of an unusually shaped

cloud).

Evidence of China's religious revival can be seen throughout the

countryside in the form of lavish new temples, halls for ancestor

worship, churches and mosques (except in the far western province of

Xinjiang, where the government worries that Islam is intertwined with

ethnic separatism and keeps tighter rein). Officially there are more

than 100m religious believers in China (see table), or about 10% of the

population. But experts say the real number is very much higher.

This does not mean that China has embraced religious freedom. Some

religions--Tibetan Buddhism, Islam as practised in Xinjiang,

Catholicism and "house church" Protestantism, which involves informal

gatherings of believers outside registered churches--are still subject

to tight controls because of the party's fears that their followers

might have an anti-government bent. A seven-year-old crackdown on Falun

Gong, a quasi-Buddhist sect that flourished in the 1990s, is still

being pursued with ruthless intensity. Many Falun Gong practitioners,

as well as lesser numbers of followers of other faiths who refuse to

accept state attempts to regulate their religions, are imprisoned in

labour camps.

Within the party, however, debate is growing about whether it should

take a different approach to religion. This does not mean being more

liberal towards what it regards as anti-government activities. But it

could mean toning down the party's atheist rhetoric and showing

stronger support for faiths that have deep historical roots among the

ethnic Han majority. The party is acutely aware that its own ideology

holds little attraction for most ordinary people. Given that many are

drawn to other beliefs, it might do better to try to win over public

opinion by actively supporting these beliefs rather than grudgingly

tolerating them or cracking down.

Pan Yue, then a senior official dealing with economic reforms and now

deputy director of the State Environmental Protection Administration,

argued in an article published in 2001 that the party's traditional

view of religion was wrong. Marx, he said, did not mean to imply that

religion was a bad thing when he referred to it as the opium of the

people. Religion, he said, could just as easily exist in socialist

societies as it does in capitalist ones. He also singled out Buddhism

and Taoism for having helped to bolster social stability through

successive Chinese dynasties. Stability being of paramount concern to

the party today, Mr Pan's message was clear.

IN PRAISE OF HARMONY

His article angered party conservatives at the time: the party's

official stance is that religion will die out under socialism. But more

recently the party itself has begun to put a more positive spin on the

role of religion. Last April China organised a meeting of Buddhist

leaders from around the world in the coastal province of Zhejiang (it

did not, however, invite the Dalai Lama, Tibet's exiled spiritual

leader). The event was given considerable prominence in the official

media. The theme, "A harmonious world begins in the mind", echoed the

party's recent propaganda drive concerning the need for a "harmonious

society". It implied just what Mr Pan had suggested-- that the opium

Marx was talking about should be seen as a benign spiritual salve. In

October the party's Central Committee issued a document on how to build

a harmonious society, arguing that religion could play a "positive

role".

The party's change of tone coincides with its recent efforts to revive

traditional culture as a way of giving China, in its state of rapid

economic and social flux, a bit more cohesion. The term "harmonious

society", which in recent months has become a party mantra, sounds in

Chinese (HEXIE SHEHUI) like an allusion to classical notions of social

order in which people do not challenge their role in life and treat

each other kindly. It is, in effect, a rejection of the Marxist notion

of class struggle.

Officials are now encouraging a revival of the study of Confucianism,

a philosophy condemned by Mao as "feudal" and which can be

quasi-religious. Since 2004 China has sponsored dozens of "Confucius

Institutes" around the world, including America and Europe, to promote

the study of Chinese language and culture.

In the countryside the revival of traditional values has needed little

encouragement. Clan shrines, where ancestors are worshipped, have

sprung up in many rural areas, particularly in prosperous coastal and

southern regions. The revival of clan identity (in many villages a

substantial minority, if not a majority, of inhabitants have the same

surname, which they trace back to a common ancestor) has had a profound

impact on village politics. Those elected as village leader often owe

much of their authority to a senior position in the clan hierarchy.

Control of the ancestral shrine confers enormous power. It is often

clan chiefs, rather than party officials, who mediate disputes. The

shrine will lend money for business ventures--so long as the recipient

has the right name.

WHERE CHRISTIANITY IS A FEMINIST ISSUE

Ironically, the growth of clan power has helped to fuel the growth of

Christianity in some parts of the countryside. In a village in the

eastern province of Shandong, the wife of a former party secretary was

a Protestant who attended prayer meetings with her female friends.

Their religious enthusiasm was apparently fuelled by the subordinate

role of women in the clan. A married woman is expected to revere only

her husband's ancestors but is excluded from his clan hierarchy. The

fast growing house-church communities often disapprove of ancestor

worship, thus attracting women who feel fettered by clan strictures.

The parlous state of China's health-care system has also given a

powerful boost to religion. Falun Gong owed much of its success in the

1990s to claims that it could heal without the need for medicine

(cash-strapped state-run hospitals usually sell medicines to patients

at inflated prices in order to boost their revenues). In the village of

Donglu in Hebei Province, about 140km south of Beijing, Catholic nuns

have set up a three-storey clinic where they offer ophthalmic, dental

and pediatric services for what they say is a fifth of the price of

government-run clinics or private ones run for profit. A picture of

Jesus is pasted to the wall in the operating theatre.

An apparition of Mary is said to have occurred in Donglu in 1900 when

local Catholics were fighting off an assault by members of the

fanatical Boxer cult trying to destroy their church. This has made the

village a site of great devotion for Catholics. Every May for the past

decade, the police have cordoned off Donglu to prevent thousands of

Catholic pilgrims making their way to the village to celebrate the

feast of Mary. Many of the pilgrims are loyal to an underground church

which claims closer ties with Rome than the state-approved Catholic

church. Yet for all Donglu's sensitivity, the local government appears

content to let Catholics run the hospital, which is a key public

service.

Chinese officials are even urging religious organisations to learn from

Hong Kong, where religious groups run many schools and hospitals. In

late November, Ye Xiaowen, the head of the State Administration of

Religious Affairs which oversees the five officially recognised

religions, said that religious groups had helped reinforce social

stability in the former British colony with their contribution to

public services. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, who

visited China in October, wrote afterwards in the TIMES that there was

now a sense in China that civil society needed religion, with its

motivated volunteers. During his trip he remarked on an "astonishing

and quite unpredictable explosion" in Christian numbers in China in

recent years.

The party still mouths its alarmist rhetoric about what it says are

foreign efforts to use religion as a means of undermining the party's

grip on power. Yet the appointment of Pope Benedict XVI, following the

death in 2005 of John Paul II who was seen by China as a more die-hard

anti-communist, has encouraged tentative efforts by China to restore

the ties with the Vatican that were severed in 1951.

Last month the Vatican decided to appoint a commission to handle

Chinese relations. But progress has been far from smooth. On November

30th, much to the Vatican's annoyance, China's state-backed Catholic

church appointed a bishop without the Vatican's prior approval for the

third time that year. Since 2000 China had done so only with the

Vatican's tacit assent. In August, however, China released a bishop

loyal to the underground church, An Shuxin, who had been arrested a

decade earlier after leading celebrations of the feast of Mary in

Donglu.

An even more tentative rapprochement is under way with the Dalai Lama.

Since 2002, China has held five rounds of talks with his

representatives, most recently last February. But China retains

profound fears that the Dalai Lama's real intention is to separate

Tibet, and adjoining areas, from China (see article[1]).

Notwithstanding the government's suspicions, Tibetan Buddhism has

acquired a certain chic in Chinese cities in recent years, with some

urbanites regarding it as spiritually more pure than Chinese-style

Buddhism, which has strong links to the government.

Within its own ranks, the party knows that some members practise

religion even though this is against the party's rules. Falun Gong

claimed many adherents among party members in the 1990s. In the

countryside, party secretaries routinely take part in religious

ceremonies. Mr Wang at the Black Dragon is not a party member, but in

other villages in the region temple chiefs double up as village party

bosses. If the party is still trying to keep its members atheist, it is

fighting a losing battle.

One result of allowing religion to play a bigger role in providing

education could be that the party finds its efforts to inculcate its

ideology among the nation's youth becoming ever more frustrated. In

Hongliutan, the temple-sponsored middle school attracts many boarders

from the town--a reversal of the normal flow of village pupils to the

towns. Thanks to the temple's sponsorship, the middle school's fees are

half of what they would be at a government school, teachers say. With

this sort of discount, the popularity and influence of the Black

Dragon, and other such spiritual beasts, seems certain to spread.