'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Wednesday, 27 August 2025

Saturday, 18 May 2024

The Epidemic of Bogus Science

Anjana Ahuja in The FT

The 1996 paper is now legendary in academic circles. “Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity”, penned by the mathematician Alan Sokal, was published in a cultural-studies journal. It claimed that physical reality was a social and linguistic construct.

Saturday, 4 May 2024

How Disinformation Works

From The Economist

Did you know that the wildfires which ravaged Hawaii last summer were started by a secret “weather weapon” being tested by America’s armed forces, and that American ngos were spreading dengue fever in Africa? That Olena Zelenska, Ukraine’s first lady, went on a $1.1m shopping spree on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue? Or that Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, has been endorsed in a new song by Mahendra Kapoor, an Indian singer who died in 2008?

These stories are, of course, all bogus. They are examples of disinformation: falsehoods that are intended to deceive. Such tall tales are being spread around the world by increasingly sophisticated campaigns. Whizzy artificial-intelligence (ai) tools and intricate networks of social-media accounts are being used to make and share eerily convincing photos, video and audio, confusing fact with fiction. In a year when half the world is holding elections, this is fuelling fears that technology will make disinformation impossible to fight, fatally undermining democracy. How worried should you be?

Disinformation has existed for as long as there have been two sides to an argument. Rameses II did not win the battle of Kadesh in 1274bc. It was, at best, a draw; but you would never guess that from the monuments the pharaoh built in honour of his triumph. Julius Caesar’s account of the Gallic wars is as much political propaganda as historical narrative. The age of print was no better. During the English civil war of the 1640s, press controls collapsed, prompting much concern about “scurrilous and fictitious pamphlets”.

The internet has made the problem much worse. False information can be distributed at low cost on social media; ai also makes it cheap to produce. Much about disinformation is murky. But in a special Science & technology section, we trace the complex ways in which it is seeded and spread via networks of social-media accounts and websites. Russia’s campaign against Ms Zelenska, for instance, began as a video on YouTube, before passing through African fake-news websites and being boosted by other sites and social-media accounts. The result is a deceptive veneer of plausibility.

Spreader accounts build a following by posting about football or the British royal family, gaining trust before mixing in disinformation. Much of the research on disinformation tends to focus on a specific topic on a particular platform in a single language. But it turns out that most campaigns work in similar ways. The techniques used by Chinese disinformation operations to bad-mouth South Korean firms in the Middle East, for instance, look remarkably like those used in Russian-led efforts to spread untruths around Europe.

The goal of many operations is not necessarily to make you support one political party over another. Sometimes the aim is simply to pollute the public sphere, or sow distrust in media, governments, and the very idea that truth is knowable. Hence the Chinese fables about weather weapons in Hawaii, or Russia’s bid to conceal its role in shooting down a Malaysian airliner by promoting several competing narratives.

All this prompts concerns that technology, by making disinformation unbeatable, will threaten democracy itself. But there are ways to minimise and manage the problem.

Encouragingly, technology is as much a force for good as it is for evil. Although ai makes the production of disinformation much cheaper, it can also help with tracking and detection. Even as campaigns become more sophisticated, with each spreader account varying its language just enough to be plausible, ai models can detect narratives that seem similar. Other tools can spot dodgy videos by identifying faked audio, or by looking for signs of real heartbeats, as revealed by subtle variations in the skin colour of people’s foreheads.

Better co-ordination can help, too. In some ways the situation is analogous to climate science in the 1980s, when meteorologists, oceanographers and earth scientists could tell something was happening, but could each see only part of the picture. Only when they were brought together did the full extent of climate change become clear. Similarly, academic researchers, ngos, tech firms, media outlets and government agencies cannot tackle the problem of disinformation on their own. With co-ordination, they can share information and spot patterns, enabling tech firms to label, muzzle or remove deceptive content. For instance, Facebook’s parent, Meta, shut down a disinformation operation in Ukraine in late 2023 after receiving a tip-off from Google.

But deeper understanding also requires better access to data. In today’s world of algorithmic feeds, only tech companies can tell who is reading what. Under American law these firms are not obliged to share data with researchers. But Europe’s new Digital Services Act mandates data-sharing, and could be a template for other countries. Companies worried about sharing secret information could let researchers send in programs to be run, rather than sending out data for analysis.

Such co-ordination will be easier to pull off in some places than others. Taiwan, for instance, is considered the gold standard for dealing with disinformation campaigns. It helps that the country is small, trust in the government is high and the threat from a hostile foreign power is clear. Other countries have fewer resources and weaker trust in institutions. In America, alas, polarised politics means that co-ordinated attempts to combat disinformation have been depicted as evidence of a vast left-wing conspiracy to silence right-wing voices online.

One person’s fact...

The dangers of disinformation need to be taken seriously and studied closely. But bear in mind that they are still uncertain. So far there is little evidence that disinformation alone can sway the outcome of an election. For centuries there have been people who have peddled false information, and people who have wanted to believe them. Yet societies have usually found ways to cope. Disinformation may be taking on a new, more sophisticated shape today. But it has not yet revealed itself as an unprecedented and unassailable threat.

Thursday, 17 November 2022

Friday, 29 July 2022

Sunday, 5 June 2022

Thursday, 2 September 2021

Saturday, 24 April 2021

Sunday, 10 January 2021

Friday, 15 May 2020

Why the Modi government gets away with lies, and how the opposition could change that

The Narendra Modi government announces a grand stimulus ‘package’ that it claims is worth Rs 20 lakh crore or ‘10 per cent’ of India’s GDP. But barely a fraction of it is new money being pumped into the economy. What is made to look like a stimulus is mostly a grand loan mela.

The Modi government is making hungry migrant labourers pay train fare. When this became a political hot potato, it said it was paying 85 per cent per cent of the fare and the state governments were paying the rest 15 per cent. Truth was that that 85 per cent was notional subsidy — in effect, the migrants were being charged the usual fare, and in some places, even more.

If no one else, at least the endless sea of migrant labourers would be able to see through the ‘85 per cent’ lie. It is curious that the Modi government openly lies — lies that are obvious and blatant. Just a few examples:

Narendra Modi said on the top of his voice that there had been no talk of a National Register of Citizens (NRC) in his government, when in fact both the President of India and the Home Minister had said it in Parliament.

Narendra Modi said the purpose of demonetisation was to destroy black money but when that didn’t work, his government kept changing goal-posts. Many lies to hide one truth: that demonetisation had failed.

Electoral bonds make political donations opaque, but the Modi government says they bring transparency. The full list of the Modi government’s lies could fill a library.

The Modi government has made lying an art form. This non-stop obvious lying was described by George Orwell as doublethink: “Every message from the extremely repressive leadership reverses the truth. Officials repeat ‘war is peace’ and ‘freedom is slavery,’ for example. The Ministry of Truth spreads lies. The Ministry of Love tortures lovers.”

People are thus expected to believe as true what is clearly false, and also take at face value mutually contradictory statements. The Modi government talked about NRC, but it also did not talk about it. The Modi government is making migrants pay for train fares, but at the same time, it is not charging them. Doublethink also applies other Orwellian principles — Newspeak, Doublespeak, Thoughtcrime, etc.

But why do people accept it all so willingly? Why do the people who are lied to every day go and vote for the same BJP?

There are many obvious answers to this question: weak opposition, mouthpiece media, social media manipulation, and Modi’s personality cult that makes his voters repose great faith in him.

But the lies are so obvious, you wonder why anyone would lie so obviously. Surely, when someone is caught lying they can’t be considered credible anymore?

What’s happening here is the plain assertion of power. Our politics has become a contest of who gets to lie and get away with it and who will have to go on a back-foot when their lies are caught.

When the Modi government lies so blatantly, it is basically saying: ‘Yes we will lie to make a mockery of your questions. Do what you can.’

Fire-hosing of falsehood

In 2016, Christopher Paul and Miriam Matthews wrote a paper for RAND Corporation, an American think-tank, in which they analysed propaganda techniques used by the Vladimir Putin government in Russia. They called it the “Firehose of Falsehood” (read it here). The Russian model is not to simply make you believe a lie — the lie is often so obviously a lie, you’d be a fool to believe it. The idea is to “entertain, confuse and overwhelm” the audience.

They identified four distinct features of the Putin propaganda model, all of which are true for the Modi propaganda machinery as well, as they are for Donald Trump’s.

1) High volume and multi-channel: The Modi propaganda machine will bombard people with a message through multiple channels. By “multiple” we really mean multiple — you will even see Twitter handles claiming to be Indian Muslims saying the same things as the far-Right Hindutva handles. Of course, some of the Muslim handles are fake. But when you see everyone from Akshay Kumar to Tabassum Begum support an idea, you’re inclined to doubt yourself. If everyone from Rubika Liyaquat to your WhatsApp-fed uncle is saying the same thing, it must be right. If so many people are saying the Citizenship (Amendment) Act will grant citizenship and not take it away, they must be right.

2) Rapid, continuous and repetitive: The hashtags, memes and emotionally charged videos will be ready before any announcement is made. The moment the announcement is made, both social and mainstream media will start bombarding you with messages in support of it. The volume and speed of the propaganda will barely leave you with the mind space to judge for yourself.

While the government will be careful to avoid saying it is not charging migrants, its deniable propaganda proxies will go around suggesting exactly that until the voice of the doubters has been drowned out. (A liberal journalist I know actually thought the migrants were not having to pay train fares anymore.)

3) Lacks commitment to objective reality: In other words, fake news. We know why fake news works: confirmation bias, information overload, emotional manipulation, the willingness to believe a message when it is shared by a trusted friend, and so on. There’s no dearth of this in the Modi propaganda ecosystem. There are countless fake news factories like OpIndia and Postcard News. Moreover, the mainstream media itself has been co-opted to manufacture fake news at scale, as the absolutely fictional charges of JNU students wanting India to be split into pieces (“Tukde tukde gang”) shows.

PM Modi himself is happy to lie for political posturing: from attributing a fake quote to Omar Abdullah, to saying there are no detention centres in the country, to exaggerating all kinds of data.

4) Lacks commitment to consistency: This is the bit where the fake news and claims are exposed, and yet they don’t hurt the leader. One day the Modi government says demonetisation is for destroying black money and next day it says it was to push cashless transactions, and third day it says the idea was to widen the tax base.

Ordinarily, such contradictions should hurt the credibility of Modi and his government. But, coupled with the three points above, the RAND researchers suggest, “fire hosing” manages to sell the changed narrative as new information, a change of opinion, or just new, advanced or supplementary facts presented by different actors.

How to fight the fire-hosing of falsehood

The RAND corporation researchers also suggest five ways for the United States to counter the Russian “fire-hosing of falsehood”. These are applicable to any actor who undertakes this propaganda model, including Modi and Trump.

1. First Information Report: Try to be the first in presenting information on a particular issue. In shaping public opinion, the first impression can be the last impression. (With our lazy opposition, this ain’t happening, but the Congress party’s announcement of paying train fares for migrant labourers was one example of creating the first impression of an issue.)

2. Highlight the lying, not just the lies: The world needs fact-checkers, but they’re not going to be able to stop the fire-hosing of falsehood. That’s like taking paracetamol for Covid-19. You may need it for the fever, but it won’t kill the virus.What might treat the virus of fire-hosing, however, according to the RAND researchers, is to chip away at the credibility of the liar by simply pointing out that he’s a serial liar. M.K. Gandhi’s assertion of truth as the core of his politics, for example, served the purpose of painting the British colonial rule as being based on falsehoods.

3. Identify and attack the goal of the propaganda: Instead of simply fact-checking the propaganda, the political opponents need to understand the objective of the lies and attack those. So, if the objective of lying about migrants having to pay for train fares is to not let them travel for free, the opposition should spend great time and energy addressing migrant labourers about how the government is being insensitive to their plight. This will take a lot more work on the ground, and simply tweeting facts won’t be enough.

4. Compete: Across the world, fire-hosing of falsehood is becoming a powerful propaganda tool. Those who want to defeat such propaganda may have to do their own fire-hosing of falsehood. As the Hindi saying goes, iron cuts iron. When public opinion is being manipulated with fake news and lies, the opposition cannot win the game with mere fact-checking. It may have to do its own rapid and continuous misinformation with little regard for the truth. The RAND researchers suggest this is what the US should do against Russia.

5. Turn off the tap: Lastly, attack the opponent’s supply chain of lies. If opposition-ruled states are not cracking down on fake news and communal hate-mongers in their states, for example, they’re making a huge mistake.

Thursday, 19 September 2019

Why can’t we agree on what’s true anymore?

We live in a time of political fury and hardening cultural divides. But if there is one thing on which virtually everyone is agreed, it is that the news and information we receive is biased. Every second of every day, someone is complaining about bias, in everything from the latest movie reviews to sports commentary to the BBC’s coverage of Brexit. These complaints and controversies take up a growing share of public discussion.

Much of the outrage that floods social media, occasionally leaking into opinion columns and broadcast interviews, is not simply a reaction to events themselves, but to the way in which they are reported and framed. The “mainstream media” is the principle focal point for this anger. Journalists and broadcasters who purport to be neutral are a constant object of scrutiny and derision, whenever they appear to let their personal views slip. The work of journalists involves an increasing amount of unscripted, real-time discussion, which provides an occasionally troubling window into their thinking.

But this is not simply an anti-journalist sentiment. A similar fury can just as easily descend on a civil servant or independent expert whenever their veneer of neutrality seems to crack, apparently revealing prejudices underneath. Sometimes a report or claim is dismissed as biased or inaccurate for the simple reason that it is unwelcome: to a Brexiter, every bad economic forecast is just another case of the so-called project fear. A sense that the game is rigged now fuels public debate.

This mentality now spans the entire political spectrum and pervades societies around the world. A recent survey found that the majority of people globally believe their society is broken and their economy is rigged. Both the left and the right feel misrepresented and misunderstood by political institutions and the media, but the anger is shared by many in the liberal centre, who believe that populists have gamed the system to harvest more attention than they deserve. Outrage with “mainstream” institutions has become a mass sentiment.

This spirit of indignation was once the natural property of the left, which has long resented the establishment bias of the press. But in the present culture war, the right points to universities, the BBC and civil service as institutions that twist our basic understanding of reality to their own ends. Everyone can point to evidence that justifies their outrage. This arms race in cultural analysis is unwinnable.

This is not as simple as distrust. The appearance of digital platforms, smartphones and the ubiquitous surveillance they enable has ushered in a new public mood that is instinctively suspicious of anyone claiming to describe reality in a fair and objective fashion. It is a mindset that begins with legitimate curiosity about what motivates a given media story, but which ends in a Trumpian refusal to accept any mainstream or official account of the world. We can all probably locate ourselves somewhere on this spectrum, between the curiosity of the engaged citizen and the corrosive cynicism of the climate denier. The question is whether this mentality is doing us any good, either individually or collectively.

Public life has become like a play whose audience is unwilling to suspend disbelief. Any utterance by a public figure can be unpicked in search of its ulterior motive. As cynicism grows, even judges, the supposedly neutral upholders of the law, are publicly accused of personal bias. Once doubt descends on public life, people become increasingly dependent on their own experiences and their own beliefs about how the world really works. One effect of this is that facts no longer seem to matter (the phenomenon misleadingly dubbed “post-truth”). But the crisis of democracy and of truth are one and the same: individuals are increasingly suspicious of the “official” stories they are being told, and expect to witness things for themselves.

On one level, heightened scepticism towards the establishment is a welcome development. A more media-literate and critical citizenry ought to be less easy for the powerful to manipulate. It may even represent a victory for the type of cultural critique pioneered by intellectuals such as Pierre Bourdieu and Stuart Hall in the 1970s and 80s, revealing the injustices embedded in everyday cultural expressions and interactions.

But it is possible to have too much scepticism. How exactly do we distinguish this critical mentality from that of the conspiracy theorist, who is convinced that they alone have seen through the official version of events? Or to turn the question around, how might it be possible to recognise the most flagrant cases of bias in the behaviour of reporters and experts, but nevertheless to accept that what they say is often a reasonable depiction of the world?

It is tempting to blame the internet, populists or foreign trolls for flooding our otherwise rational society with lies. But this underestimates the scale of the technological and philosophical transformations that are under way. The single biggest change in our public sphere is that we now have an unimaginable excess of news and content, where once we had scarcity. Suddenly, the analogue channels and professions we depended on for our knowledge of the world have come to seem partial, slow and dispensable.

And yet, contrary to initial hype surrounding big data, the explosion of information available to us is making it harder, not easier, to achieve consensus on truth. As the quantity of information increases, the need to pick out bite-size pieces of content rises accordingly. In this radically sceptical age, questions of where to look, what to focus on and who to trust are ones that we increasingly seek to answer for ourselves, without the help of intermediaries. This is a liberation of sorts, but it is also at the heart of our deteriorating confidence in public institutions.

The current threat to democracy is often seen to emanate from new forms of propaganda, with the implication that lies are being deliberately fed to a naive and over-emotional public. The simultaneous rise of populist parties and digital platforms has triggered well-known anxieties regarding the fate of truth in democratic societies. Fake news and internet echo chambers are believed to manipulate and ghettoise certain communities, for shadowy ends. Key groups – millennials or the white working-class, say – are accused of being easily persuadable, thanks to their excessive sentimentality.

This diagnosis exaggerates old-fashioned threats while overlooking new phenomena. Over-reliant on analogies to 20th century totalitarianism, it paints the present moment as a moral conflict between truth and lies, with an unthinking public passively consuming the results. But our relationship to information and news is now entirely different: it has become an active and critical one, that is deeply suspicious of the official line. Nowadays, everyone is engaged in spotting and rebutting propaganda of one kind or another, curating our news feeds, attacking the framing of the other side and consciously resisting manipulation. In some ways, we have become too concerned with truth, to the point where we can no longer agree on it. The very institutions that might once have brought controversies to an end are under constant fire for their compromises and biases.

The threat of misinformation and propaganda should not be denied. As the scholars Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris and Hal Roberts have shown in their book Network Propaganda, there is now a self-sustaining information ecosystem on the American right through which conspiracy theories and untruths get recycled, between Breitbart, Fox News, talk radio and social media. Meanwhile, the anti-vaxx movement is becoming a serious public health problem across the world, aided by the online circulation of conspiracy theories and pseudo-science. This is a situation where simple misinformation poses a serious threat to society.

But away from these eye-catching cases, things look less clear-cut. The majority of people in northern Europe still regularly encounter mainstream news and information. Britain is a long way from the US experience, thanks principally to the presence of the BBC, which, for all its faults, still performs a basic function in providing a common informational experience. It is treated as a primary source of news by 60% of people in the UK. Even 42% of Brexit party and Ukip voters get their news from the BBC.

The panic surrounding echo chambers and so-called filter bubbles is largely groundless. If we think of an echo chamber as a sealed environment, which only circulates opinions and facts that are agreeable to its participants, it is a rather implausible phenomenon. Research by the Oxford Internet Institute suggests that just 8% of the UK public are at risk of becoming trapped in such a clique.

Trust in the media is low, but this entrenched scepticism long predates the internet or contemporary populism. From the Sun’s lies about Hillsborough to the BBC’s failure to expose Jimmy Savile as early as they might, to the fevered enthusiasm for the Iraq war that gripped much of Fleet Street, the British public has had plenty of good reasons to distrust journalists. Even so, the number of people in the UK who trust journalists to tell the truth has actually risen slightly since the 1980s.

What, then, has changed? The key thing is that the elites of government and the media have lost their monopoly over the provision of information, but retain their prominence in the public eye. They have become more like celebrities, anti-heroes or figures in a reality TV show. And digital platforms now provide a public space to identify and rake over the flaws, biases and falsehoods of mainstream institutions. The result is an increasingly sceptical citizenry, each seeking to manage their media diet, checking up on individual journalists in order to resist the pernicious influence of the establishment.

There are clear and obvious benefits to this, where it allows hateful and manipulative journalism to be called out. It is reassuring to discover the large swell of public sympathy for the likes of Ben Stokes and Gareth Thomas, and their families, who have been harassed by the tabloids in recent days. But this also generates a mood of outrage, which is far more focused on denouncing bad and biased reporting than with defending the alternative. Across the political spectrum, we are increasingly distracted and enraged by what our adversaries deem important and how they frame it. It is not typically the media’s lies that provoke the greatest fury online, but the discovery that an important event has been ignored or downplayed. While it is true that arguments rage over dodgy facts and figures (concerning climate change or the details of Britain’s trading relations), many of the most bitter controversies of our news cycle concern the framing and weighting of different issues and how they are reported, rather than the facts of what actually happened.

The problem we face is not, then, that certain people are oblivious to the “mainstream media”, or are victims of fake news, but that we are all seeking to see through the veneer of facts and information provided to us by public institutions. Facts and official reports are no longer the end of the story. Such scepticism is healthy and, in many ways, the just deserts of an establishment that has been caught twisting the truth too many times. But political problems arise once we turn against all representations and framings of reality, on the basis that these are compromised and biased – as if some purer, unmediated access to the truth might be possible instead. This is a seductive, but misleading ideal.

Every human culture throughout history has developed ways to record experiences and events, allowing them to endure. From early modern times, liberal societies have developed a wide range of institutions and professions whose work ensures that events do not simply pass without trace or public awareness. Newspapers and broadcasters share reports, photographs and footage of things that have happened in politics, business, society and culture. Court documents and the Hansard parliamentary reports provide records of what has been said in court and in parliament. Systems of accounting, audit and economics help to establish basic facts of what takes place in businesses and markets.

Traditionally, it is through these systems, which are grounded in written testimonies and public statements, that we have learned what is going on in the world. But in the past 20 years, this patchwork of record-keeping has been supplemented and threatened by a radically different system, which is transforming the nature of empirical evidence and memory. One term for this is “big data”, which highlights the exponential growth in the quantity of data that societies create, thanks to digital technologies.

The reason there is so much data today is that more and more of our social lives are mediated digitally. Internet browsers, smartphones, social media platforms, smart cards and every other smart interface record every move we make. Whether or not we are conscious of it, we are constantly leaving traces of our activities, no matter how trivial.

But it is not the escalating quantity of data that constitutes the radical change. Something altogether new has occurred that distinguishes today’s society from previous epochs. In the past, recording devices were principally trained upon events that were already acknowledged as important. Journalists did not just report news, but determined what counted as newsworthy. TV crews turned up at events that were deemed of national significance. The rest of us kept our cameras for noteworthy occasions, such as holidays and parties.

The ubiquity of digital technology has thrown all of this up in the air. Things no longer need to be judged “important” to be captured. Consciously, we photograph events and record experiences regardless of their importance. Unconsciously, we leave a trace of our behaviour every time we swipe a smart card, address Amazon’s Alexa or touch our phone. For the first time in human history, recording now happens by default, and the question of significance is addressed separately.

This shift has prompted an unrealistic set of expectations regarding possibilities for human knowledge. As many of the original evangelists of big data liked to claim, when everything is being recorded, our knowledge of the world no longer needs to be mediated by professionals, experts, institutions and theories. Instead, they argued that the data can simply “speak for itself”. Patterns will emerge, traces will come to light. This holds out the prospect of some purer truth than the one presented to us by professional editors or trained experts. As the Australian surveillance scholar Mark Andrejevic has brilliantly articulated, this is a fantasy of a truth unpolluted by any deliberate human intervention – the ultimate in scientific objectivity.

Andrejevic argues that the rise of this fantasy coincides with growing impatience with the efforts of reporters and experts to frame reality in meaningful ways. He writes that “we might describe the contemporary media moment – and its characteristic attitude of sceptical savviness regarding the contrivance of representation – as one that implicitly embraces the ideal of framelessness”. From this perspective, every controversy can in principle be settled thanks to the vast trove of data – CCTV, records of digital activity and so on – now available to us. Reality in its totality is being recorded, and reporters and officials look dismally compromised by comparison.

One way in which seemingly frameless media has transformed public life over recent years is in the elevation of photography and video as arbiters of truth, as opposed to written testimony or numbers. “Pics or it didn’t happen” is a jokey barb sometimes thrown at social media users when they share some unlikely experience. It is often a single image that seems to capture the truth of an event, only now there are cameras everywhere. No matter how many times it is disproven, the notion that “the camera doesn’t lie” has a peculiar hold over our imaginations. In a society of blanket CCTV and smartphones, there are more cameras than people, and the torrent of data adds to the sense that the truth is somewhere amid the deluge, ignored by mainstream accounts. The central demand of this newly sceptical public is “so show me”.

This transformation in our recording equipment is responsible for much of the outrage directed at those formerly tasked with describing the world. The rise of blanket surveillance technologies has paradoxical effects, raising expectations for objective knowledge to unrealistic levels, and then provoking fury when those in the public eye do not meet them.

On the one hand, data science appears to make the question of objective truth easier to settle. Slow and imperfect institutions of social science and journalism can be circumvented, and we can get directly to reality itself, unpolluted by human bias. Surely, in this age of mass data capture, the truth will become undeniable.

On the other hand, as the quantity of data becomes overwhelming – greater than human intelligence can comprehend – our ability to agree on the nature of reality seems to be declining. Once everything is, in principle, recordable, disputes heat up regarding what counts as significant in the first place. It turns out that the “frames” that journalists and experts use to reduce and organise information are indispensable to its coherence and meaning.

What we are discovering is that, once the limitations on data capture are removed, there are escalating opportunities for conflict over the nature of reality. Every time a mainstream media agency reports the news, they can instantly be met with the retort: but what about this other event, in another time and another place, that you failed to report? What about the bits you left out? What about the other voters in the town you didn’t talk to? When editors judge the relative importance of stories, they now confront a panoply of alternative judgements. Where records are abundant, fights break out over relevance and meaning.

Professional editors have always faced the challenge of reducing long interviews to short consumable chunks and discarding the majority of photos or text. Editing is largely a question of what to throw away. This necessitates value judgements, that readers and audiences once had little option but to trust. Now, however, the question of which image or sentence is truly significant opens irresolvable arguments. One person’s offcut is another person’s revealing nugget.

Political agendas can be pursued this way, including cynical ones aimed at painting one’s opponents in the worst possible light. An absurd or extreme voice can be represented as typical of a political movement (known as “nutpicking”). Taking quotes out of context is one of the most disruptive of online ploys, which provokes far more fury than simple insults. Rather than deploying lies or “fake news”, it messes with the significance of data, taking the fact that someone did say or write something, but violating their intended meaning. No doubt professional journalists have always descended to such tactics from time to time, but now we are all at it, provoking a vicious circle of misrepresentation.

Then consider the status of photography and video. It is not just that photographic evidence can be manipulated to mislead, but that questions will always survive regarding camera angle and context. What happened before or after a camera started rolling? What was outside the shot? These questions provoke suspicion, often with good reason.

The most historic example of such a controversy predates digital media. The Zapruder film, which captured the assassination of John F Kennedy, became the most scrutinised piece of footage in history. The film helped spawn countless conspiracy theories, with individual frames becoming the focus of controversies, with competing theories as to what they reveal. The difficulty of completely squaring any narrative with a photographic image is a philosophical one as much as anything, and the Zapruder film gave a glimpse of the sorts of media disputes that have become endemic now cameras are ubiquitous parts of our social lives and built environments.

Minor gestures pored over for hidden meanings … Emily Maitlis (left) with Nadhim Zahawi and Barry Gardiner on the BBC’s Newsnight. Photograph: BBC

Today, minor gestures that would usually have passed without comment only a decade ago become pored over in search of their hidden message. What did Emily Maitlis mean when she rolled her eyes at Barry Gardiner on Newsnight? What was Jeremy Corbyn mouthing during Prime Minister’s Questions? Who took the photo of Boris Johnson and Carrie Symonds sitting at a garden table in July, and why? This way madness lies.

While we are now able to see evidence for ourselves, we all have conflicting ideas of what bit to attend to, and what it means. The camera may not lie, but that is because it does not speak at all. As we become more fixated on some ultimate gold-standard of objective truth, which exceeds the words of mere journalists or experts, so the number of interpretations applied to the evidence multiplies. As our faith in the idea of undeniable proof deepens, so our frustration with competing framings and official accounts rises. All too often, the charge of “bias” means “that’s not my perspective”. Our screen-based interactions with many institutions have become fuelled by anger that our experiences are not being better recognised, along with a new pleasure at being able to complain about it. As the writer and programmer Paul Ford wrote, back in 2011, “the fundamental question of the web” is: “Why wasn’t I consulted?”

What we are witnessing is a collision between two conflicting ideals of truth: one that depends on trusted intermediaries (journalists and experts), and another that promises the illusion of direct access to reality itself. This has echoes of the populist challenge to liberal democracy, which pits direct expressions of the popular will against parliaments and judges, undermining the very possibility of compromise. The Brexit crisis exemplifies this as well as anything. Liberals and remainers adhere to the long-standing constitutional convention that the public speaks via the institutions of general elections and parliament. Adamant Brexiters believe that the people spoke for themselves in June 2016, and have been thwarted ever since by MPs and civil servants. It is this latter logic that paints suspending parliament as an act of democracy.

This is the tension that many populist leaders exploit. Officials and elected politicians are painted as cynically self-interested, while the “will of the people” is both pure and obvious. Attacks on the mainstream media follow an identical script: the individuals professionally tasked with informing the public, in this case journalists, are biased and fake. It is widely noted that leaders such as Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro and Matteo Salvini are enthusiastic users of Twitter, and Boris Johnson has recently begun to use Facebook Live to speak directly to “the people” from Downing Street. Whether it be parliaments or broadcasters, the analogue intermediaries of the public sphere are discredited and circumvented.

What can professional editors and journalists do in response? One response is to shout even louder about their commitment to “truth”, as some American newspapers have profitably done in the face of Trump. But this escalates cultural conflict, and fails to account for how the media and informational landscape has changed in the past 20 years.

What if, instead, we accepted the claim that all reports about the world are simply framings of one kind or another, which cannot but involve political and moral ideas about what counts as important? After all, reality becomes incoherent and overwhelming unless it is simplified and narrated in some way or other. And what if we accepted that journalists, editors and public figures will inevitably let cultural and personal biases slip from time to time? A shrug is often the more appropriate response than a howl. If we abandoned the search for some pure and unbiased truth, where might our critical energies be directed instead?

If we recognise that reporting and editing is always a political act (at least in the sense that it asserts the importance of one story rather than another), then the key question is not whether it is biased, but whether it is independent of financial or political influence. The problem becomes a quasi-constitutional one, of what processes, networks and money determine how data gets turned into news, and how power gets distributed. On this front, the British media is looking worse and worse, with every year that passes.

The relationship between the government and the press has been getting tighter since the 1980s. This is partly thanks to the overweening power of Rupert Murdoch, and the image management that developed in response. Spin doctors such as Alastair Campbell, Andy Coulson, Tom Baldwin, Robbie Gibb and Seumas Milne typically move from the media into party politics, weakening the division between the two.

Then there are those individuals who shift backwards and forwards between senior political positions and the BBC, such as Gibb, Rona Fairhead and James Purnell. The press has taken a very bad turn over recent years, with ex-Chancellor George Osborne becoming editor of the Evening Standard, then the extraordinary recent behaviour of the Daily Telegraph, which seeks to present whatever story or gloss is most supportive of their former star columnist in 10 Downing Street, and rubbishes his opponents. (The Opinion page of the Telegraph website proudly includes a “Best of Boris” section.)

Since the financial crisis of 2008, there have been regular complaints about the revolving door between the financial sector and governmental institutions around the world, most importantly the White House. There has been far less criticism of the similar door that links the media and politics. The exception to this comes from populist leaders, who routinely denounce all “mainstream” democratic and media institutions as a single liberal elite, that acts against the will of the people. One of the reasons they are able to do this is because there is a grain of truth in what they say.

The financial obstacles confronting critical, independent, investigative media are significant. If the Johnson administration takes a more sharply populist turn, the political obstacles could increase, too – Channel 4 is frequently held up as an enemy of Brexit, for example. But let us be clear that an independent, professional media is what we need to defend at the present moment, and abandon the misleading and destructive idea that – thanks to a combination of ubiquitous data capture and personal passions – the truth can be grasped directly, without anyone needing to report it.

Wednesday, 13 February 2019

Dark money is pushing for a no-deal Brexit. Who is behind it?

Modern governments respond to only two varieties of emergency: those whose solution is bombs and bullets, and those whose solution is bailouts for the banks. But what if they decided to take other threats as seriously?

This week’s revelations of a catastrophic collapse in insect populations, jeopardising all terrestrial life, would prompt the equivalent of an emergency meeting of the UN security council. The escalating disasters of climate breakdown and soil loss would trigger spending at least as great as the quantitative easing after the financial crisis. Instead, politicians carry on as if nothing is amiss.

The same goes for the democratic emergency. Almost everywhere trust in governments, parliaments and elections is collapsing. Shared civic life is replaced by closed social circles that receive entirely different, often false, information. The widespread sense that politics has become so corrupted that it can no longer respond to ordinary people’s needs has provoked a demagogic backlash that in some countries begins to slide into fascism. But despite years of revelations about hidden spending, fake news, front groups and micro-targeted ads on social media, almost nothing has changed.

In Britain, for example, we now know that the EU referendum was won with the help of widespread cheating. We still don’t know the origins of much of the money spent by the leave campaigns. For example, we have no idea who provided the £435,000 channelled through Scotland, into Northern Ireland, through the coffers of the Democratic Unionist party and back into Scotland and England, to pay for pro-Brexit ads. Nor do we know the original source of the £8m that Arron Banks delivered to the Leave.EU campaign. We do know that both of the main leave campaigns have been fined for illegal activities, and that the conduct of the referendum has damaged many people’s faith in the political system. But, astonishingly, the government has so far failed to introduce a single new law in response to these events. And now it’s happening again.

Since mid-January an organisation called Britain’s Future has spent £125,000 on Facebook ads demanding a hard or no-deal Brexit. Most of them target particular constituencies. Where an MP is deemed sympathetic to the organisation’s aims, the voters who receive these ads are urged to tell him or her to “remove the backstop, rule out a customs union, deliver Brexit without delay”. Where the MP is deemed unsympathetic, the message is: “Don’t let them steal Brexit; Don’t let them ignore your vote.”

So who or what is Britain’s Future? Sorry, I have no idea. As openDemocracy points out, it has no published address and releases no information about who founded it, who controls it and who has been paying for these advertisements. The only person publicly associated with it is a journalist called Tim Dawson, who edits its website. Dawson has not yet replied to the questions I have sent him. It is, in other words, highly opaque. The anti-Brexit campaigns are not much better. People’s Vote and Best for Britain have also been spending heavily on Facebook ads, though not as much in recent weeks as Britain’s Future.

At least we know who is involved in these remain campaigns and where they are based, but both refuse to reveal their full sources of funding. People’s Vote says “the majority of our funding comes from small donors”. It also receives larger donations but says “it’s a matter for the donors if they want to go public”. Best for Britain says that some of its funders want to remain anonymous, and “we understand that”. But it seems to me that that transparent and accountable campaigns would identify anyone paying more than a certain amount (perhaps £1,000). If people don’t want to be named, they shouldn’t use their money to influence our politics. Both campaigns insist that they abide by the rules governing funding for political parties, elections and referendums.

As they must know better than most, the rules on such spending are next to useless. They were last redrafted 19 years ago, when online campaigning had scarcely begun. It’s as if current traffic regulations insisted only that you water your horses every few hours and check the struts on your cartwheels for woodworm. The Electoral Commission has none of the powers required to regulate online campaigning or to extract information from companies such as Facebook. Nor does it have the power to determine the original sources of money spent on political campaigns. So it is unable to tell whether or not the law that says funders must be based in the UK has been broken. The maximum fines it can levy are pathetic: £20,000 for each offence. That’s a small price to pay for winning an election.

Since 2003, the commission has been asking, with an ever greater sense of urgency, for basic changes in the law. But it has been stonewalled by successive governments. The exposés of Carole Cadwalladr, the Guardian, openDemocracy and Channel 4 News about the conduct of the referendum have so far made no meaningful difference to government policy. We have local elections in May and there could be a general election at any time. The old, defunct rules still apply.

Our politicians have instead left it to Facebook to do the right thing. Which is, shall we say, an unreliable strategy. In response to the public outcry, Facebook now insists that organisations placing political ads provide it (but not us) with a contact based in the UK. Since October, it has archived their advertisements and the amount they spend. But there is no requirement that its advertisers reveal who provides the funding. An organisation’s name means nothing if the organisation is opaque. The way Facebook presents the data makes it impossible to determine spending trends, unless you check the entries every week. And its new rules apply only in the US, the UK and Brazil. In the rest of the world, it remains a regulatory black hole.

So why won’t the government act? Partly because, regardless of the corrosive impacts on public life, it wants to keep the system as it is. The current rules favour the parties with the most money to spend, which tends to mean the parties that appeal to the rich. But mostly, I think, it’s because, like other governments, it has become institutionally incapable of responding to our emergencies. It won’t rescue democracy because it can’t. The system in which it is embedded seems destined to escalate rather than dampen disasters.

Ecologically, economically and politically, capitalism is failing as catastrophically as communism failed. Like state communism, it is beset by unacknowledged but fatal contradictions. It is inherently corrupt and corrupting. But its mesmerising power, and the vast infrastructure of thought that seeks to justify it, makes any challenge to the model almost impossible to contemplate. Even to acknowledge the emergencies it causes, let alone to act on them, feels like electoral suicide. As the famous saying goes: “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.” Our urgent task is to turn this the other way round.

Wednesday, 30 May 2018

How to defeat fake news: Lessons from Ireland's abortion referendum

In all the excitement of what happened in Ireland’s referendum on abortion, we should not lose sight of what did not happen. A vote on an emotive subject was not subverted. The tactics that have been so successful for the right and the far right in the UK, the US, Hungary and elsewhere did not work. A democracy navigated its way through some very rough terrain and came home not just alive but more alive than it was before. In the world we inhabit, these things are worth celebrating but also worth learning from. Political circumstances are never quite the same twice, but some of what happened and did not happen in Ireland surely contains more general lessons.

If the right failed spectacularly in Ireland, it was not for want of trying. Save the 8th, one of the two main groups campaigning against the removal of the anti-abortion clause from the Irish constitution, hired Vote Leave’s technical director, the Cambridge Analytica alumnus Thomas Borwick.

Save the 8th and the other anti-repeal campaign, Love Both, used apps developed by a US-based company, Political Social Media (PSM), which worked on both the Brexit and Trump campaigns. The small print told those using the apps that their data could be shared with other PSM clients, including the Trump campaign, the Republican National Committee and Vote Leave.

Irish voters were subjected to the same polarising tactics that have worked so well elsewhere: shamelessly fake “facts” (the claim, for example, that abortion was to be legalised up to six months into pregnancy); the contemptuous dismissal of expertise (the leading obstetrician Peter Boylan was told in a TV debate to “go back to school”); deliberately shocking visual imagery (posters of aborted foetuses outside maternity hospitals); and a discourse of liberal elites versus the real people. But Irish democracy had an immune system that proved highly effective in resisting this virus. Its success suggests a democratic playbook with at least four good rules.

It was these citizens who suggested entirely unrestricted access to abortion up to 12 weeks. Conservatives dismissed this process, in Trump style, as rigged (it wasn’t). They would have been much better off if they had actually listened to what these citizens were saying, and tried to understand what had persuaded them to take such a liberal position. The Irish parliament did listen – an all-party parliamentary committee essentially adopted the proposals of the Citizens’ Assembly. So did the government. And it turned out that a sample of “the people” actually knew pretty well what “the people” were thinking. If the Brexit referendum had been preceded by such a respectful, dignified and humble exercise in listening and thinking, it would surely have been a radically different experience.

Second, be honest. The yes side in the Irish debate handed its opponents a major tactical advantage but gained a huge strategic victory. It ceded an advantage in playing with all its cards turned up on the table. Technically, the vote was merely to repeal a clause in the constitution. There was no need to say what legislation the government hoped to enact afterwards. But the government chose to be completely clear about its intentions. It published a draft bill. This allowed opponents of reform to pick at, and often distort, points of detail. But it also completely undercut the reactionary politics of paranoia, the spectre of secret conspiracies. Honesty proved to be very good policy.

Yes campaigners did not assume that an elderly lady going to mass in a rural village was a lost cause

Third, talk to everybody and make assumptions about nobody. The reactionary movements have been thriving on tribalism. They divide voters into us and them – and all the better if they call us “deplorables”. The yes campaigners in Ireland – many of them young people, who are so often caricatured as the inhabitants of virtual echo chambers – refused to be tribal. They stayed calm and dignified. And when they were jeered at, they did not jeer back. They got out and talked (and listened) without prejudice. They did not assume that an elderly lady going to mass in a rural village was a lost cause. They risked (and sometimes got) abuse by recognising no comfort zones and engaging everyone they could reach. It turned out that a lot of people were sick of being typecast as conservatives. It turned out that a lot of people like to be treated as complex, intelligent and compassionate individuals. A majority of farmers and more than 40% of the over-65s voted yes.

Finally, the old feminist slogan that the personal is political holds true, but it also works the other way around. The political has to be personalised. The greatest human immune system against the viruses of hysteria, hatred and lies is storytelling. Even when we don’t trust politicians or experts, we trust people telling their own tales. We trust ourselves to judge whether they are lying or being truthful. Irish women had to go out and tell their own stories, to make the painful and intimate into public property.

This is very hard to do, and it should not be necessary. But is unstoppably powerful. The process mattered, political leadership mattered, campaigning mattered. But it was stories that won. Exit polls showed that by far the biggest factors in determining how people voted were “people’s personal stories that were told to the media”, followed by “the experience of someone who they know”.

Women, in the intimate circles of family and friends or in the harsh light of TV studios, said: “This is who I am. I am one of you.” And voters responded: “Yes, you are.” If democracy can create the context for that humane exchange to happen over and over again, it can withstand everything its enemies throw at it.

Sunday, 29 April 2018

Fake five-star reviews being bought and sold online

Fake online reviews are being openly traded on the internet, a BBC investigation has found.

BBC 5 live Investigates was able to buy a false, five-star recommendation placed on one of the world's leading review websites, Trustpilot.

It also uncovered online forums where Amazon shoppers are offered full refunds in exchange for product reviews.

Both companies said they do not tolerate false reviews.

'Trying to game the system'

The popularity of online review sites mean they are increasingly relied on by both businesses and their customers, with the government's Competition and Markets Authority estimating such reviews potentially influence £23 billion of UK customer spending every year.

Maria Menelaou, whose Yorkshire Fisheries chip shop is the top-ranked fish and chip shop in Blackpool on several review sites, said the system has replaced traditional advertising.

"It brings us a lot of customers ... It really does make a difference. We don't do any kind of advertising," Mrs Menelaou said.

While three quarters of UK adults use online review websites, almost half of those believe they have seen fake reviews, according to a survey of 1500 UK residents conducted by the Chartered Institute of Marketing and shared with BBC 5 live Investigates.

Some US analysts estimate as many as half of the reviews for certain products posted on international websites such as Amazon are potentially unreliable.

"Sellers are trying to game the system and there's a lot of money on the table," said Tommy Noonan, who runs ReviewMeta, a US-based website that analyses online reviews.

"If you can rank number one for, say, bluetooth headsets and you're selling a cheap product, you can make a lot of money," he said.

'5 star is better for us'

Mr Noonan said this effectively drove the problem underground, leading to the emergence of Facebook groups where potential Amazon customers were encouraged to buy a product and post a review in return for a full refund.

BBC 5 live Investigates identified several of these groups and, within minutes of joining, was approached with offers of full refunds on products bought on Amazon in exchange for positive reviews.

"5 star is better for us" said one person making such an offer, in an exchange of messages with the BBC. "We value our brand, will refund you as we promised ... All my company do in this way."

It was not possible to identify the people making these offers, nor contact the businesses whose products they were seeking reviews for.

"We do not permit reviews in exchange for compensation of any kind, including payment. Customers and Marketplace sellers must follow our review guidelines and those that don't will be subject to action including potential termination of their account," Amazon said in a statement.

Responding to adverts posted on eBay, the BBC was also able to purchase a false 5-star review on Trustpilot, an online review website that describes itself as "committed to being the most trusted online review community on the market".

"Dan Box is one of the most respected professionals I have dealt with. It was a pleasure doing business with him," this review said - word for word as requested by 5 live Investigates.

Trustpilot, whose platform allows anyone to post a review, said they have "a zero-tolerance policy towards any misuse".

"We have specialist software that screens reviews against 100's of data points around the clock to automatically identify and remove fakes," the company said.

In a statement, eBay said the sale of such reviews is banned from its platform "and any listings will be removed".

Sunday, 12 November 2017

Nudging can also be used for dark purposes

“If you want people to do the right thing, make it easy.” That is the simplest possible summary of Nudge by Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler. We are all fallible creatures, and so benevolent policymakers need to make sure that the path of least resistance goes to a happy destination. It is a simple but important idea, and deservedly influential: Mr Sunstein became a senior adviser to President Obama, while Mr Thaler is this year’s winner of the Nobel memorial prize in economics.

Monday, 25 September 2017

Dead Cats - Fatal attraction of fake facts sours political debate

He did it again: Boris Johnson, UK foreign secretary, exhumed the old referendum-campaign lie that leaving the EU would free up £350m a week for the National Health Service. I think we can skip the well-worn details, because while the claim is misleading, its main purpose is not to mislead but to distract. The growing popularity of this tactic should alarm anyone who thinks that the truth still matters.

Monday, 8 May 2017

The great British Brexit robbery: how our democracy was hijacked

Alex Younger, head of MI6, December, 2016

Senior intelligence analyst, April 2017

In June 2013, a young American postgraduate called Sophie was passing through London when she called up the boss of a firm where she’d previously interned. The company, SCL Elections, went on to be bought by Robert Mercer, a secretive hedge fund billionaire, renamed Cambridge Analytica, and achieved a certain notoriety as the data analytics firm that played a role in both Trump and Brexit campaigns. But all of this was still to come. London in 2013 was still basking in the afterglow of the Olympics. Britain had not yet Brexited. The world had not yet turned.

“That was before we became this dark, dystopian data company that gave the world Trump,” a former Cambridge Analytica employee who I’ll call Paul tells me. “It was back when we were still just a psychological warfare firm.”

Was that really what you called it, I ask him. Psychological warfare? “Totally. That’s what it is. Psyops. Psychological operations – the same methods the military use to effect mass sentiment change. It’s what they mean by winning ‘hearts and minds’. We were just doing it to win elections in the kind of developing countries that don’t have many rules.”

Why would anyone want to intern with a psychological warfare firm, I ask him. And he looks at me like I am mad. “It was like working for MI6. Only it’s MI6 for hire. It was very posh, very English, run by an old Etonian and you got to do some really cool things. Fly all over the world. You were working with the president of Kenya or Ghana or wherever. It’s not like election campaigns in the west. You got to do all sorts of crazy shit.”

On that day in June 2013, Sophie met up with SCL’s chief executive, Alexander Nix, and gave him the germ of an idea. “She said, ‘You really need to get into data.’ She really drummed it home to Alexander. And she suggested he meet this firm that belonged to someone she knew about through her father.”

Who’s her father?

“Eric Schmidt.”

Eric Schmidt – the chairman of Google?

“Yes. And she suggested Alexander should meet this company called Palantir.”

I had been speaking to former employees of Cambridge Analytica for months and heard dozens of hair-raising stories, but it was still a gobsmacking moment. To anyone concerned about surveillance, Palantir is practically now a trigger word. The data-mining firm has contracts with governments all over the world – including GCHQ and the NSA. It’s owned by Peter Thiel, the billionaire co-founder of eBay and PayPal, who became Silicon Valley’s first vocal supporter of Trump.

In some ways, Eric Schmidt’s daughter showing up to make an introduction to Palantir is just another weird detail in the weirdest story I have ever researched.

A weird but telling detail. Because it goes to the heart of why the story of Cambridge Analytica is one of the most profoundly unsettling of our time. Sophie Schmidt now works for another Silicon Valley megafirm: Uber. And what’s clear is that the power and dominance of the Silicon Valley – Google and Facebook and a small handful of others – are at the centre of the global tectonic shift we are currently witnessing.

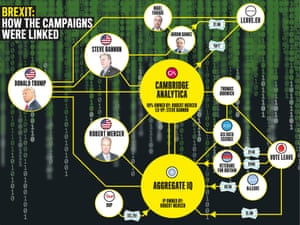

The money man: Robert Mercer, Trump supporter and owner of Cambridge Analytica. Photograph: Rex

It also reveals a critical and gaping hole in the political debate in Britain. Because what is happening in America and what is happening in Britain are entwined. Brexit and Trump are entwined. The Trump administration’s links to Russia and Britain are entwined. And Cambridge Analytica is one point of focus through which we can see all these relationships in play; it also reveals the elephant in the room as we hurtle into a general election: Britain tying its future to an America that is being remade - in a radical and alarming way - by Trump.

There are three strands to this story. How the foundations of an authoritarian surveillance state are being laid in the US. How British democracy was subverted through a covert, far-reaching plan of coordination enabled by a US billionaire. And how we are in the midst of a massive land grab for power by billionaires via our data. Data which is being silently amassed, harvested and stored. Whoever owns this data owns the future.

My entry point into this story began, as so many things do, with a late-night Google. Last December, I took an unsettling tumble into a wormhole of Google autocompletesuggestions that ended with “did the holocaust happen”. And an entire page of results that claimed it didn’t.

Google’s algorithm had been gamed by extremist sites and it was Jonathan Albright, a professor of communications at Elon University, North Carolina, who helped me get to grips with what I was seeing. He was the first person to map and uncover an entire “alt-right” news and information ecosystem and he was the one who first introduced me to Cambridge Analytica.

He called the company a central point in the right’s “propaganda machine”, a line I quoted in reference to its work for the Trump election campaign and the referendum Leave campaign. That led to the second article featuring Cambridge Analytica – as a central node in the alternative news and information network that I believed Robert Mercer and Steve Bannon, the key Trump aide who is now his chief strategist, were creating. I found evidence suggesting they were on a strategic mission to smash the mainstream media and replace it with one comprising alternative facts, fake history and rightwing propaganda.

Mercer is a brilliant computer scientist, a pioneer in early artificial intelligence, and the co-owner of one of the most successful hedge funds on the planet (with a gravity-defying 71.8% annual return). And, he is also, I discovered, good friends with Nigel Farage. Andy Wigmore, Leave.EU’s communications director, told me that it was Mercer who had directed his company, Cambridge Analytica, to “help” the Leave campaign.

The second article triggered two investigations, which are both continuing: one by the Information Commissioner’s Office into the possible illegal use of data. And a second by the Electoral Commission which is “focused on whether one or more donations – including services – accepted by Leave.EU was ‘impermissable’”.

What I then discovered is that Mercer’s role in the referendum went far beyond this. Far beyond the jurisdiction of any UK law. The key to understanding how a motivated and determined billionaire could bypass ourelectoral laws rests on AggregateIQ, an obscure web analytics company based in an office above a shop in Victoria, British Columbia.

It was with AggregateIQ that Vote Leave (the official Leave campaign) chose to spend £3.9m, more than half its official £7m campaign budget. As did three other affiliated Leave campaigns: BeLeave, Veterans for Britain and the Democratic Unionist party, spending a further £757,750. “Coordination” between campaigns is prohibited under UK electoral law, unless campaign expenditure is declared, jointly. It wasn’t. Vote Leave says the Electoral Commission “looked into this” and gave it “a clean bill of health”.

How did an obscure Canadian company come to play such a pivotal role in Brexit? It’s a question that Martin Moore, director of the centre for the study of communication, media and power at King’s College London has been asking too. “I went through all the Leave campaign invoices when the Electoral Commission uploaded them to its site in February. And I kept on discovering all these huge amounts going to a company that not only had I never heard of, but that there was practically nothing at all about on the internet. More money was spent with AggregateIQ than with any other company in any other campaign in the entire referendum. All I found, at that time, was a one-page website and that was it. It was an absolute mystery.”

Moore contributed to an LSE report published in April that concluded UK’s electoral laws were “weak and helpless” in the face of new forms of digital campaigning. Offshore companies, money poured into databases, unfettered third parties… the caps on spending had come off. The laws that had always underpinned Britain’s electoral laws were no longer fit for purpose. Laws, the report said, that needed “urgently reviewing by parliament”.

AggregateIQ holds the key to unravelling another complicated network of influence that Mercer has created. A source emailed me to say he had found that AggregateIQ’s address and telephone number corresponded to a company listed on Cambridge Analytica’s website as its overseas office: “SCL Canada”. A day later, that online reference vanished.

There had to be a connection between the two companies. Between the various Leave campaigns. Between the referendum and Mercer. It was too big a coincidence. But everyone – AggregateIQ, Cambridge Analytica, Leave.EU, Vote Leave – denied it. AggregateIQ had just been a short-term “contractor” to Cambridge Analytica. There was nothing to disprove this. We published the known facts. On 29 March, article 50 was triggered.

Then I meet Paul, the first of two sources formerly employed by Cambridge Analytica. He is in his late 20s and bears mental scars from his time there. “It’s almost like post-traumatic shock. It was so… messed up. It happened so fast. I just woke up one morning and found we’d turned into the Republican fascist party. I still can’t get my head around it.”

He laughed when I told him the frustrating mystery that was AggregateIQ. “Find Chris Wylie,” he said.

Who’s Chris Wylie?

“He’s the one who brought data and micro-targeting [individualised political messages] to Cambridge Analytica. And he’s from west Canada. It’s only because of him that AggregateIQ exist. They’re his friends. He’s the one who brought them in.”

There wasn’t just a relationship between Cambridge Analytica and AggregateIQ, Paul told me. They were intimately entwined, key nodes in Robert Mercer’s distributed empire. “The Canadians were our back office. They built our software for us. They held our database. If AggregateIQ is involved then Cambridge Analytica is involved. And if Cambridge Analytica is involved, then Robert Mercer and Steve Bannon are involved. You need to find Chris Wylie.”

I did find Chris Wylie. He refused to comment.

Key to understanding how data would transform the company is knowing where it came from. And it’s a letter from “Director of Defence Operations, SCL Group”, that helped me realise this. It’s from “Commander Steve Tatham, PhD, MPhil, Royal Navy (rtd)” complaining about my use in my Mercer article of the word “disinformation”.

I wrote back to him pointing out references in papers he’d written to “deception” and “propaganda”, which I said I understood to be “roughly synonymous with ‘disinformation’.” It’s only later that it strikes me how strange it is that I’m corresponding with a retired navy commander about military strategies that may have been used in British and US elections.

What’s been lost in the US coverage of this “data analytics” firm is the understanding of where the firm came from: deep within the military-industrial complex. A weird British corner of it populated, as the military establishment in Britain is, by old-school Tories. Geoffrey Pattie, a former parliamentary under-secretary of state for defence procurement and director of Marconi Defence Systems, used to be on the board, and Lord Marland, David Cameron’s pro-Brexit former trade envoy, a shareholder.

Steve Tatham was the head of psychological operations for British forces in Afghanistan. The Observer has seen letters endorsing him from the UK Ministry of Defence, the Foreign Office and Nato.

SCL/Cambridge Analytica was not some startup created by a couple of guys with a Mac PowerBook. It’s effectively part of the British defence establishment. And, now, too, the American defence establishment. An ex-commanding officer of the US Marine Corps operations centre, Chris Naler, has recently joined Iota Global, a partner of the SCL group.

This is not just a story about social psychology and data analytics. It has to be understood in terms of a military contractor using military strategies on a civilian population. Us. David Miller, a professor of sociology at Bath University and an authority in psyops and propaganda, says it is “an extraordinary scandal that this should be anywhere near a democracy. It should be clear to voters where information is coming from, and if it’s not transparent or open where it’s coming from, it raises the question of whether we are actually living in a democracy or not.”

Paul and David, another ex-Cambridge Analytica employee, were working at the firm when it introduced mass data-harvesting to its psychological warfare techniques. “It brought psychology, propaganda and technology together in this powerful new way,” David tells me.

And it was Facebook that made it possible. It was from Facebook that Cambridge Analytica obtained its vast dataset in the first place. Earlier, psychologists at Cambridge University harvested Facebook data (legally) for research purposes and published pioneering peer-reviewed work about determining personality traits, political partisanship, sexuality and much more from people’s Facebook “likes”. And SCL/Cambridge Analytica contracted a scientist at the university, Dr Aleksandr Kogan, to harvest new Facebook data. And he did so by paying people to take a personality quiz which also allowed not just their own Facebook profiles to be harvested, but also those of their friends – a process then allowed by the social network.

Facebook was the source of the psychological insights that enabled Cambridge Analytica to target individuals. It was also the mechanism that enabled them to be delivered on a large scale.

The company also (perfectly legally) bought consumer datasets – on everything from magazine subscriptions to airline travel – and uniquely it appended these with the psych data to voter files. It matched all this information to people’s addresses, their phone numbers and often their email addresses. “The goal is to capture every single aspect of every voter’s information environment,” said David. “And the personality data enabled Cambridge Analytica to craft individual messages.”

Finding “persuadable” voters is key for any campaign and with its treasure trove of data, Cambridge Analytica could target people high in neuroticism, for example, with images of immigrants “swamping” the country. The key is finding emotional triggers for each individual voter.

Cambridge Analytica worked on campaigns in several key states for a Republican political action committee. Its key objective, according to a memo the Observer has seen, was “voter disengagement” and “to persuade Democrat voters to stay at home”: a profoundly disquieting tactic. It has previously been claimed that suppression tactics were used in the campaign, but this document provides the first actual evidence.

But does it actually work? One of the criticisms that has been levelled at my and others’ articles is that Cambridge Analytica’s “special sauce” has been oversold. Is what it is doing any different from any other political consultancy?

“It’s not a political consultancy,” says David. “You have to understand this is not a normal company in any way. I don’t think Mercer even cares if it ever makes any money. It’s the product of a billionaire spending huge amounts of money to build his own experimental science lab, to test what works, to find tiny slivers of influence that can tip an election. Robert Mercer did not invest in this firm until it ran a bunch of pilots – controlled trials. This is one of the smartest computer scientists in the world. He is not going to splash $15m on bullshit.”

Tamsin Shaw, an associate professor of philosophy at New York University, helps me understand the context. She has researched the US military’s funding and use of psychological research for use in torture. “The capacity for this science to be used to manipulate emotions is very well established. This is military-funded technology that has been harnessed by a global plutocracy and is being used to sway elections in ways that people can’t even see, don’t even realise is happening to them,” she says. “It’s about exploiting existing phenomenon like nationalism and then using it to manipulate people at the margins. To have so much data in the hands of a bunch of international plutocrats to do with it what they will is absolutely chilling.

“We are in an information war and billionaires are buying up these companies, which are then employed to go to work in the heart of government. That’s a very worrying situation.”

A project that Cambridge Analytica carried out in Trinidad in 2013 brings all the elements in this story together. Just as Robert Mercer began his negotiations with SCL boss Alexander Nix about an acquisition, SCL was retained by several government ministers in Trinidad and Tobago. The brief involved developing a micro-targeting programme for the governing party of the time. And AggregateIQ – the same company involved in delivering Brexit for Vote Leave – was brought in to build the targeting platform.

David said: “The standard SCL/CA method is that you get a government contract from the ruling party. And this pays for the political work. So, it’s often some bullshit health project that’s just a cover for getting the minister re-elected. But in this case, our government contacts were with Trinidad’s national security council.”