'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Farage. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Farage. Show all posts

Friday, 30 June 2023

Wednesday, 21 June 2023

Luck and Politics

Bagehot in The Economist

Monday june 19th was a typical day in British politics insofar as it involved a series of humiliations for the Conservative Party. mps approved a report on Boris Johnson condemning the former prime minister for lying to Parliament over lockdown-busting parties. Rishi Sunak skipped proceedings for a fortunately timed meeting with Sweden’s prime minister. On the same day, the invite emerged for an illegal “Jingle and Mingle” event at the party’s headquarters during the Christmas lockdown of 2020. A video of the event had already circulated, with one staffer overheard saying it was fine “as long as we don’t stream that we’re, like, bending the rules”. Labour, through no efforts of their own, had their reputation comparatively enhanced.

Luck is an overlooked part of politics. It is in the interests of both politicians and those who write about them to pretend it plays little role. Yet, as much as strategy or skill, luck determines success. “Fortune is the mistress of one half of our actions, and yet leaves the control of the other half, or a little less, to ourselves,” wrote Machiavelli in “The Prince” in the 16th century. Some polls give Labour a 20-point lead. Partly this is because, under Sir Keir Starmer, they have jettisoned the baggage of the Jeremy Corbyn-era and painted a picture of unthreatening economic diligence. Mainly it is because they are damned lucky.

If Sir Keir does have a magic lamp, it has been buffed to a blinding sheen. After all, it is not just the behaviour of Mr Johnson that helps Labour. Britain is suffering from a bout of economic pain in a way that particularly hurts middle-class mortgage holders, who are crucial marginal voters. Even the timing helps. Rather than a single hit, the pain will be spread out until 2024, when the general election comes due. Each quarter next year, about 350,000 households will re-mortgage and become, on average, almost £3,000 ($3,830) per year worse off, according to the Resolution Foundation. Labour strategists could barely dream of a more helpful backdrop.

Political problems that once looked intractable for Labour have solved themselves. Scotland was supposed to be a Gordian knot. How could a unionist party such as Labour tempt left-wing voters of the nationalist Scottish National Party (snp)? The police have fixed that. Nicola Sturgeon, the most talented Scottish politician of her generation, found herself arrested and quizzed over an illicit £100,000 camper van and other matters to do with party funds. The snp’s poll rating has collapsed and another 25 seats are set to fall into the Labour leader’s lap thanks to pc McPlod and (at best) erratic book-keeping by the snp.

It is not the first time police have come to Sir Keir’s aid. He promised to quit in 2022 if police fined him for having a curry and beer with campaigners during lockdown-affected local elections in 2021. Labour’s advisers were adamant no rules were broken. But police forces were erratic in dishing out penalties, veering between lax and draconian. It was a risk. Sir Keir gambled and won.

Luck will always play a large role in a first-past-the-post system that generates big changes in electoral outcomes from small shifts in voting. Margins are often tiny. Mr Corbyn came, according to one very optimistic analysis, within 2,227 votes of scraping a majority in the 2017 general election, if they had fallen in the right places. Likewise, in 2021, Labour faced a by-election in Batley and Spen, in Yorkshire. A defeat would almost certainly have triggered a leadership challenge; Labour clung on, narrowly, and so did Sir Keir. If he enters Downing Street in 2024, he will have 323 voters just outside Leeds to thank.

Sir Keir is hardly the first leader to benefit from fortune’s favour. Good ones have always needed it. Sir Tony Blair reshaped Labour and won three general elections. But he only had the job because John Smith, his predecessor, dropped dead at 55. (“He’s fat, he’s 53, he’s had a heart attack and he’s taking on a stress-loaded job” the Sun had previously written, with unkind foresight.) Without the Falklands War in 1982, Margaret Thatcher would have asked for re-election soon afterwards based on a few years of a faltering experiment with monetarism. Formidable political talent is nothing without a dash of luck.

Often the most consequential politicians are the luckiest. Nigel Farage has a good claim to be the most influential politician of the past 20 years. He should also be dead. The former leader of the uk Independence Party was run over in 1985. Then, in 1987, testicular cancer nearly killed him. In 2010, he survived a plane crash after a banner—“Vote for your country—Vote ukip”—became tangled around the plane. Smaller factors also played in Mr Farage’s favour: when he was a member of the European Parliament he was randomly allocated a seat next to the European Commission president, providing a perfect backdrop for viral speeches. (“They handed me the internet on a plate!” chortles Mr Farage.) Britain left the eu, in part, because Mr Farage is lucky.

Stop polishing that lamp, you’ll go blind

Too much good luck can be a bad thing. David Cameron gambled three times on referendums (on the country’s voting system, on Scottish independence and on Brexit). He won two heavily and lost one narrowly. Two out of three ain’t bad, but it is enough to condemn him as one of the worst prime ministers on record. “A Prince who rests wholly on fortune is ruined when she changes,” wrote Machivelli. It was right in 1516; it was right in 2016. Labour would do well to heed the lesson. It sometimes comes across as a party that expects the Conservatives to lose, rather than one thinking how best to win.

Fortune has left Labour in a commanding position. Arguments against a Labour majority rely on hope (perhaps inflation will come down sharply) not expectation. Good luck may power Labour to victory in 2024, but it will not help them govern. The last time Labour replaced the Conservatives, in 1997, the economy was flying. Now, debt is over 100% of gdp. Growth prospects are lacking, while public services are failing. It will be a horrible time to run the country. Bad luck.

Monday june 19th was a typical day in British politics insofar as it involved a series of humiliations for the Conservative Party. mps approved a report on Boris Johnson condemning the former prime minister for lying to Parliament over lockdown-busting parties. Rishi Sunak skipped proceedings for a fortunately timed meeting with Sweden’s prime minister. On the same day, the invite emerged for an illegal “Jingle and Mingle” event at the party’s headquarters during the Christmas lockdown of 2020. A video of the event had already circulated, with one staffer overheard saying it was fine “as long as we don’t stream that we’re, like, bending the rules”. Labour, through no efforts of their own, had their reputation comparatively enhanced.

Luck is an overlooked part of politics. It is in the interests of both politicians and those who write about them to pretend it plays little role. Yet, as much as strategy or skill, luck determines success. “Fortune is the mistress of one half of our actions, and yet leaves the control of the other half, or a little less, to ourselves,” wrote Machiavelli in “The Prince” in the 16th century. Some polls give Labour a 20-point lead. Partly this is because, under Sir Keir Starmer, they have jettisoned the baggage of the Jeremy Corbyn-era and painted a picture of unthreatening economic diligence. Mainly it is because they are damned lucky.

If Sir Keir does have a magic lamp, it has been buffed to a blinding sheen. After all, it is not just the behaviour of Mr Johnson that helps Labour. Britain is suffering from a bout of economic pain in a way that particularly hurts middle-class mortgage holders, who are crucial marginal voters. Even the timing helps. Rather than a single hit, the pain will be spread out until 2024, when the general election comes due. Each quarter next year, about 350,000 households will re-mortgage and become, on average, almost £3,000 ($3,830) per year worse off, according to the Resolution Foundation. Labour strategists could barely dream of a more helpful backdrop.

Political problems that once looked intractable for Labour have solved themselves. Scotland was supposed to be a Gordian knot. How could a unionist party such as Labour tempt left-wing voters of the nationalist Scottish National Party (snp)? The police have fixed that. Nicola Sturgeon, the most talented Scottish politician of her generation, found herself arrested and quizzed over an illicit £100,000 camper van and other matters to do with party funds. The snp’s poll rating has collapsed and another 25 seats are set to fall into the Labour leader’s lap thanks to pc McPlod and (at best) erratic book-keeping by the snp.

It is not the first time police have come to Sir Keir’s aid. He promised to quit in 2022 if police fined him for having a curry and beer with campaigners during lockdown-affected local elections in 2021. Labour’s advisers were adamant no rules were broken. But police forces were erratic in dishing out penalties, veering between lax and draconian. It was a risk. Sir Keir gambled and won.

Luck will always play a large role in a first-past-the-post system that generates big changes in electoral outcomes from small shifts in voting. Margins are often tiny. Mr Corbyn came, according to one very optimistic analysis, within 2,227 votes of scraping a majority in the 2017 general election, if they had fallen in the right places. Likewise, in 2021, Labour faced a by-election in Batley and Spen, in Yorkshire. A defeat would almost certainly have triggered a leadership challenge; Labour clung on, narrowly, and so did Sir Keir. If he enters Downing Street in 2024, he will have 323 voters just outside Leeds to thank.

Sir Keir is hardly the first leader to benefit from fortune’s favour. Good ones have always needed it. Sir Tony Blair reshaped Labour and won three general elections. But he only had the job because John Smith, his predecessor, dropped dead at 55. (“He’s fat, he’s 53, he’s had a heart attack and he’s taking on a stress-loaded job” the Sun had previously written, with unkind foresight.) Without the Falklands War in 1982, Margaret Thatcher would have asked for re-election soon afterwards based on a few years of a faltering experiment with monetarism. Formidable political talent is nothing without a dash of luck.

Often the most consequential politicians are the luckiest. Nigel Farage has a good claim to be the most influential politician of the past 20 years. He should also be dead. The former leader of the uk Independence Party was run over in 1985. Then, in 1987, testicular cancer nearly killed him. In 2010, he survived a plane crash after a banner—“Vote for your country—Vote ukip”—became tangled around the plane. Smaller factors also played in Mr Farage’s favour: when he was a member of the European Parliament he was randomly allocated a seat next to the European Commission president, providing a perfect backdrop for viral speeches. (“They handed me the internet on a plate!” chortles Mr Farage.) Britain left the eu, in part, because Mr Farage is lucky.

Stop polishing that lamp, you’ll go blind

Too much good luck can be a bad thing. David Cameron gambled three times on referendums (on the country’s voting system, on Scottish independence and on Brexit). He won two heavily and lost one narrowly. Two out of three ain’t bad, but it is enough to condemn him as one of the worst prime ministers on record. “A Prince who rests wholly on fortune is ruined when she changes,” wrote Machivelli. It was right in 1516; it was right in 2016. Labour would do well to heed the lesson. It sometimes comes across as a party that expects the Conservatives to lose, rather than one thinking how best to win.

Fortune has left Labour in a commanding position. Arguments against a Labour majority rely on hope (perhaps inflation will come down sharply) not expectation. Good luck may power Labour to victory in 2024, but it will not help them govern. The last time Labour replaced the Conservatives, in 1997, the economy was flying. Now, debt is over 100% of gdp. Growth prospects are lacking, while public services are failing. It will be a horrible time to run the country. Bad luck.

Thursday, 8 June 2023

McCarthyism rises in Labour as it readies for power

Having examined how the North of Tyne mayor was barred from standing again, I see something akin to McCarthyism writes Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

I first met the man who has been all over this week’s political headlines four years ago, 300 miles up the A1 from Westminster. It was a bitterly cold Saturday morning in the Northumberland coastal town of Newbiggin and Jamie Driscoll was asking for votes. He’d just caused a minor political earthquake by winning Labour members’ support to run for the new position of mayor of North of Tyne. The cert for that role had been Nick Forbes, Newcastle council leader and longtime big beast – not Driscoll, who had been a local councillor for a few months and who, on winning the selection, had had to rush out to buy his only suit.

I watched this stubbly, scruffy, upbeat outsider doorknock around an estate of small houses and exotic garden statuettes, to a reaction chillier than the wind whipping in from the North Sea. For decades, this had been Labour country, where that political tradition ran through the local economy, its institutions and people’s very identities. But over the past 50 years all that had been destroyed and now it was the land of Vote Leave, desolate and nihilistic. If residents spoke to canvassers at all, it was to spit out statements like “I don’t follow politics”.

After more slammed doors, one activist sighed: “Policy doesn’t matter here. They’ve forgotten what government can do.” For all Driscoll’s ideas and energy, I wrote at the time, his biggest challenge would be closing the vast gulf between the governed and their governors.

That tableau has come to mind many times since the Labour party barred Driscoll from standing for re-election. No more will he trigger democratic earthquakes. Instead, he has become fodder for lobby journalists. When I met him in Newcastle this week, he was slaloming between interviews for Radio 4, ITV, national newspapers, Newsnight and more. The ending of his political career has done more for his national profile than four years in office. I listened as each outlet demanded its shot of Westminster caffeine. Hardly anyone asked what it meant for the north-east, for local democracy, for the people in Newbiggin and anyone else who long ago tuned out all politicians as fraudulent liars only in it for themselves.

And why wouldn’t they? I have chased down and sifted through evidence, much of it never revealed before, and it points to a stitch-up bigger than anything on the Great Sewing Bee. The jumped-up outsider, Driscoll, has been tossed in the bin – but he is merely collateral damage in a one-sided Labour factional fight, whose actors appear not to give a damn for people’s reputations or for the public they’re meant to serve.

Let’s work backwards. Labour officials blocked Driscoll last Friday, soon after he’d been interviewed by a panel drawn largely from the party’s national executive committee. The email he received reads: “[T]he NEC panel has determined that you will not be progressing further as a candidate in this process.” But while the party gave no official reason to the candidate, its enforcers were happy to brief lobby journalists – who in turn quoted anonymous sources that it was because in March he had appeared at a Newcastle theatre with Ken Loach to discuss his films. The renowned director had been expelled as a Labour member in 2021.

I first met the man who has been all over this week’s political headlines four years ago, 300 miles up the A1 from Westminster. It was a bitterly cold Saturday morning in the Northumberland coastal town of Newbiggin and Jamie Driscoll was asking for votes. He’d just caused a minor political earthquake by winning Labour members’ support to run for the new position of mayor of North of Tyne. The cert for that role had been Nick Forbes, Newcastle council leader and longtime big beast – not Driscoll, who had been a local councillor for a few months and who, on winning the selection, had had to rush out to buy his only suit.

I watched this stubbly, scruffy, upbeat outsider doorknock around an estate of small houses and exotic garden statuettes, to a reaction chillier than the wind whipping in from the North Sea. For decades, this had been Labour country, where that political tradition ran through the local economy, its institutions and people’s very identities. But over the past 50 years all that had been destroyed and now it was the land of Vote Leave, desolate and nihilistic. If residents spoke to canvassers at all, it was to spit out statements like “I don’t follow politics”.

After more slammed doors, one activist sighed: “Policy doesn’t matter here. They’ve forgotten what government can do.” For all Driscoll’s ideas and energy, I wrote at the time, his biggest challenge would be closing the vast gulf between the governed and their governors.

That tableau has come to mind many times since the Labour party barred Driscoll from standing for re-election. No more will he trigger democratic earthquakes. Instead, he has become fodder for lobby journalists. When I met him in Newcastle this week, he was slaloming between interviews for Radio 4, ITV, national newspapers, Newsnight and more. The ending of his political career has done more for his national profile than four years in office. I listened as each outlet demanded its shot of Westminster caffeine. Hardly anyone asked what it meant for the north-east, for local democracy, for the people in Newbiggin and anyone else who long ago tuned out all politicians as fraudulent liars only in it for themselves.

And why wouldn’t they? I have chased down and sifted through evidence, much of it never revealed before, and it points to a stitch-up bigger than anything on the Great Sewing Bee. The jumped-up outsider, Driscoll, has been tossed in the bin – but he is merely collateral damage in a one-sided Labour factional fight, whose actors appear not to give a damn for people’s reputations or for the public they’re meant to serve.

Let’s work backwards. Labour officials blocked Driscoll last Friday, soon after he’d been interviewed by a panel drawn largely from the party’s national executive committee. The email he received reads: “[T]he NEC panel has determined that you will not be progressing further as a candidate in this process.” But while the party gave no official reason to the candidate, its enforcers were happy to brief lobby journalists – who in turn quoted anonymous sources that it was because in March he had appeared at a Newcastle theatre with Ken Loach to discuss his films. The renowned director had been expelled as a Labour member in 2021.

Jamie Driscoll addresses the Transport for the North conference in March. Photograph: Ian Forsyth/Getty Images

On Sunday, Labour frontbencher Jonathan Reynolds told Sky News that Driscoll was excluded for sharing a platform with “someone who themselves has been expelled for their views on antisemitism” – a line swiftly amplified by the media, yet not quite true. I asked Loach’s office to forward his letters of expulsion, which say only that he is “ineligible” due to his support of “a political organisation other than an official Labour group”. That was Labour Against the Witchhunt, which did claim allegations of Labour antisemitism were “politically motivated”. Reynolds was conflating the two. I asked how many other journalists had sought clarification. The answer was one.

A column about Driscoll is not the place to litigate Ken Loach’s views, even if I disagree with much of what he says about Labour’s treatment of antisemitism. It barely needs saying that sitting on stage with a director to discuss their films does not mean you share all their opinions. Far more troubling for British democracy is how anonymous, factional briefings are simply machine-pressed into newspaper “facts” then spewed out on TV.

“They were always looking to get me,” Driscoll claimed this week. I have read emails dating back to 2020 where the new metro mayor asks Labour officials for the party’s local membership lists used by councillors, MPs and mayors as standard. But not here: IT issues meant the lists supposedly weren’t shareable. Until this year that is, when he was told the upcoming mayoral contest meant he could only access lists “if you make a confirmation that you are not seeking the selection”. Another email, sent by Driscoll last month to party officials, notes that a local constituency party has been told by a senior official to disinvite him from speaking.

Asked for comment, Labour didn’t reply – but this is petty, attritional stuff, which is what happens when politics is evacuated of ideas and arguments and becomes simply about who is in whose good books. Cliqueishness is hardly exclusive to Keir Starmer’s Labour, but it is starker now because instead of real politics all this lot have is office politics.

Which brings us back to the much-discussed NEC panel, supposedly to divine his suitability to stand. I have viewed footage of the entire hour on Zoom, which discusses nothing of Driscoll’s beliefs or achievements. Three of the five panel members are from groups on the right of the party, and all anyone wants to know is why he spoke to Loach. They refer to the director’s “controversial views” and quote the Jewish Chronicle’s coverage. How, they ask, might the event be viewed by a “hostile media”?

Driscoll replies that Holocaust denial is “abhorrent” and that he has signed up to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of antisemitism. He recalls how he used to fight fascists in the street. None of it is good enough.

A rather bumptious young man informs the mayor that “you can’t separate someone’s views from their work”. The twentysomething declares that Driscoll shouldn’t have discussed the films but instead attacked Loach’s politics. On that basis, Starmer ought to be disqualified for appearing with Loach on the BBC’s Question Time – and so too should the shadow foreign secretary, David Lammy, who in 2019 wrote a paean in this paper to Loach’s Sorry We Missed You, praising the way it “brings across how the right to a family life has been eroded in modern Britain”.

We all know that a week is a long time in Starmer’s politics, but he did once proclaim a proud regionalism. Now what’s left?

Attacking McCarthyism, Ed Murrow told his TV audience: “We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law. We will not walk in fear, one of another.”

By these standards, Driscoll is a victim of McCarthyism. The office he holds is now a mere electoral toy to be enjoyed by a favoured faction. And those people in Newbiggin and Ashington and anyone else who might be looking on with half an eye will see nothing but machine politicians serving themselves. This was the swamp out of which Nigel Farage emerged.

On Sunday, Labour frontbencher Jonathan Reynolds told Sky News that Driscoll was excluded for sharing a platform with “someone who themselves has been expelled for their views on antisemitism” – a line swiftly amplified by the media, yet not quite true. I asked Loach’s office to forward his letters of expulsion, which say only that he is “ineligible” due to his support of “a political organisation other than an official Labour group”. That was Labour Against the Witchhunt, which did claim allegations of Labour antisemitism were “politically motivated”. Reynolds was conflating the two. I asked how many other journalists had sought clarification. The answer was one.

A column about Driscoll is not the place to litigate Ken Loach’s views, even if I disagree with much of what he says about Labour’s treatment of antisemitism. It barely needs saying that sitting on stage with a director to discuss their films does not mean you share all their opinions. Far more troubling for British democracy is how anonymous, factional briefings are simply machine-pressed into newspaper “facts” then spewed out on TV.

“They were always looking to get me,” Driscoll claimed this week. I have read emails dating back to 2020 where the new metro mayor asks Labour officials for the party’s local membership lists used by councillors, MPs and mayors as standard. But not here: IT issues meant the lists supposedly weren’t shareable. Until this year that is, when he was told the upcoming mayoral contest meant he could only access lists “if you make a confirmation that you are not seeking the selection”. Another email, sent by Driscoll last month to party officials, notes that a local constituency party has been told by a senior official to disinvite him from speaking.

Asked for comment, Labour didn’t reply – but this is petty, attritional stuff, which is what happens when politics is evacuated of ideas and arguments and becomes simply about who is in whose good books. Cliqueishness is hardly exclusive to Keir Starmer’s Labour, but it is starker now because instead of real politics all this lot have is office politics.

Which brings us back to the much-discussed NEC panel, supposedly to divine his suitability to stand. I have viewed footage of the entire hour on Zoom, which discusses nothing of Driscoll’s beliefs or achievements. Three of the five panel members are from groups on the right of the party, and all anyone wants to know is why he spoke to Loach. They refer to the director’s “controversial views” and quote the Jewish Chronicle’s coverage. How, they ask, might the event be viewed by a “hostile media”?

Driscoll replies that Holocaust denial is “abhorrent” and that he has signed up to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of antisemitism. He recalls how he used to fight fascists in the street. None of it is good enough.

A rather bumptious young man informs the mayor that “you can’t separate someone’s views from their work”. The twentysomething declares that Driscoll shouldn’t have discussed the films but instead attacked Loach’s politics. On that basis, Starmer ought to be disqualified for appearing with Loach on the BBC’s Question Time – and so too should the shadow foreign secretary, David Lammy, who in 2019 wrote a paean in this paper to Loach’s Sorry We Missed You, praising the way it “brings across how the right to a family life has been eroded in modern Britain”.

We all know that a week is a long time in Starmer’s politics, but he did once proclaim a proud regionalism. Now what’s left?

Attacking McCarthyism, Ed Murrow told his TV audience: “We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law. We will not walk in fear, one of another.”

By these standards, Driscoll is a victim of McCarthyism. The office he holds is now a mere electoral toy to be enjoyed by a favoured faction. And those people in Newbiggin and Ashington and anyone else who might be looking on with half an eye will see nothing but machine politicians serving themselves. This was the swamp out of which Nigel Farage emerged.

Sunday, 20 February 2022

Tuesday, 23 January 2018

I founded Ukip. It’s a national joke now and should disappear

Alan Sked in The Guardian

I founded the Anti-Federalist League in 1991 to take Britain out of what became the European Union. The party was renamed Ukip - the UK Independence party – in 1993 and was a thoroughly mainstream one. It had policies on a wide range of issues but not immigration, not then seen as being controversial. Its membership form stated it had no prejudices against foreigners or lawful minorities of any kind. All that changed after I resigned as leader in 1997 to devote myself exclusively to academic life.

Before I left, I expelled Nigel Farage and two others from the party. They had convened a public convention in Basingstoke to examine why I had not won the 1997 general election. Media representatives and others were invited but not me. I, of course, would have explained that with fewer than 200 candidates, only £40,000 in the bank, no media coverage or name recognition, and with a wealthy Referendum party as well as the major ones to fight, there was never any chance of winning an election.

In any case, the Ukip national executive committee expelled them for bringing the party into disrepute, but really for their embarrassing political naivety and stupidity – qualities that they infused into the party when, after a costly legal battle Ukip could not afford to continue, they were restored to membership. Farage, of course, never ever managed to get himself elected as an MP in 20 years, or get any other Ukip candidate (save a couple of Tory turncoats) into parliament.

Yet, despite the lack of brainpower, Ukip was saved from oblivion by two external factors. First, in 1999, the EU changed the voting system for the European parliament, allowing parties with very low votes to enter. This allowed Ukip to become the default protest party in European elections, although its MEPs did little other than collect their salaries and expenses.

This enabled the party to appear on the BBC’s Question Time but brought no political gains domestically. Farage was not interested in ideas, policies or recruiting decent candidates. Only immigration mattered to him. He himself could joyfully describe Ukip’s 2010 manifesto as “drivel, sheer drivel”. The party that year secured only 3.1% of the vote, and fewer than one million votes. It is important to remember this.

However, it was now saved by another external factor. Nick Clegg took the suicidal decision to enter a coalition with David Cameron’s Tories, agreed to triple university tuition fees and back austerity. All this caused the demise of the Lib Dems and their replacement by Ukip as the default protest party domestically. This was already clear by the 2012 local elections and in the 2015 general election, when Ukip won more than 11% of the vote.

By then, of course, Cameron had committed himself to a referendum on EU membership, which he lost in 2016. Michael Gove and Boris Johnson secured Brexit; Farage, a toxic and divisive figure, was kept at arm’s length and success came in spite of him, not on account of him. (Only Donald Trump believed the opposite.)

Since the referendum Ukip has fallen apart. With a leave vote achieved and Farage gone, it has suffered from poor and eccentric leadership, falling poll ratings (less than 2% in the 2017 general election) and a general perception that Brexit can be left to the Tories.

The love life of its present leader has made it a national joke and the party’s MEPs and so-called front bench have deserted him. Indeed, Ukip may not be able to afford to run a new leadership election. As its founder I can only suggest that it should now dissolve itself. There may be a need for a party to hold the Tories to account over Brexit but that is not Ukip. It now lacks all political credibility and provokes laughter rather than sympathy. It is high time therefore for it to disappear.

I founded the Anti-Federalist League in 1991 to take Britain out of what became the European Union. The party was renamed Ukip - the UK Independence party – in 1993 and was a thoroughly mainstream one. It had policies on a wide range of issues but not immigration, not then seen as being controversial. Its membership form stated it had no prejudices against foreigners or lawful minorities of any kind. All that changed after I resigned as leader in 1997 to devote myself exclusively to academic life.

Before I left, I expelled Nigel Farage and two others from the party. They had convened a public convention in Basingstoke to examine why I had not won the 1997 general election. Media representatives and others were invited but not me. I, of course, would have explained that with fewer than 200 candidates, only £40,000 in the bank, no media coverage or name recognition, and with a wealthy Referendum party as well as the major ones to fight, there was never any chance of winning an election.

In any case, the Ukip national executive committee expelled them for bringing the party into disrepute, but really for their embarrassing political naivety and stupidity – qualities that they infused into the party when, after a costly legal battle Ukip could not afford to continue, they were restored to membership. Farage, of course, never ever managed to get himself elected as an MP in 20 years, or get any other Ukip candidate (save a couple of Tory turncoats) into parliament.

Yet, despite the lack of brainpower, Ukip was saved from oblivion by two external factors. First, in 1999, the EU changed the voting system for the European parliament, allowing parties with very low votes to enter. This allowed Ukip to become the default protest party in European elections, although its MEPs did little other than collect their salaries and expenses.

This enabled the party to appear on the BBC’s Question Time but brought no political gains domestically. Farage was not interested in ideas, policies or recruiting decent candidates. Only immigration mattered to him. He himself could joyfully describe Ukip’s 2010 manifesto as “drivel, sheer drivel”. The party that year secured only 3.1% of the vote, and fewer than one million votes. It is important to remember this.

However, it was now saved by another external factor. Nick Clegg took the suicidal decision to enter a coalition with David Cameron’s Tories, agreed to triple university tuition fees and back austerity. All this caused the demise of the Lib Dems and their replacement by Ukip as the default protest party domestically. This was already clear by the 2012 local elections and in the 2015 general election, when Ukip won more than 11% of the vote.

By then, of course, Cameron had committed himself to a referendum on EU membership, which he lost in 2016. Michael Gove and Boris Johnson secured Brexit; Farage, a toxic and divisive figure, was kept at arm’s length and success came in spite of him, not on account of him. (Only Donald Trump believed the opposite.)

Since the referendum Ukip has fallen apart. With a leave vote achieved and Farage gone, it has suffered from poor and eccentric leadership, falling poll ratings (less than 2% in the 2017 general election) and a general perception that Brexit can be left to the Tories.

The love life of its present leader has made it a national joke and the party’s MEPs and so-called front bench have deserted him. Indeed, Ukip may not be able to afford to run a new leadership election. As its founder I can only suggest that it should now dissolve itself. There may be a need for a party to hold the Tories to account over Brexit but that is not Ukip. It now lacks all political credibility and provokes laughter rather than sympathy. It is high time therefore for it to disappear.

Sunday, 14 January 2018

With Farage rattled and MPs flexing their muscles, the real Brexit battle is just beginning

Toby Helm and Michael Savage in The Guardian

When Nigel Farage emerged from a meeting in Brussels with the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier shortly after midday last Monday his increasingly gloomy mood had darkened further. “The message I got was that they will be happy to trade chocolate and cheese and wine freely with us but when it comes to services, forget it. It ain’t going to happen. I think we are going to have a very bad deal.”

In the early hours of 24 June, 2016, the former Ukip leader, who had, arguably, done more than anyone to deliver the Leave vote, toured TV stations, triumphantly hailing the UK’s “independence day”. In Farage’s view it was not only a defining moment for Britain. It was also one that would demonstrate to other EU member states with strong or emerging eurosceptic movements – he cited Denmark, Italy, Sweden and Austria – that there was another way. “The EU is failing, the EU is dying. I hope that we have knocked the first brick out of the wall,” he declared in the glow of victory.

Nineteen months on, that joy and optimism have been replaced by doubt and fear. These days Farage is a genuinely worried man. He deeply regrets that the Leave campaign effectively “shut up shop” the day after the referendum, believing it was job done. The result of doing so, he told the Observer on Friday, was that the Leave side is now being seriously outgunned by well-funded, well-organised supporters of Remain who are intent on overturning the referendum result.

Three days after his meeting with Barnier, Farage went on TV again and said he was coming round to the view that a second referendum might be the only way to regain the initiative, to cement Brexit and shut down the issue for a generation. He said then that he thought Leave would win again, and by a bigger margin.

But on Friday he was less sure – and revealed the real depth and root of his anxieties. The momentum, he made clear, was running away from the Leavers. They had vacated the field for Remain to run all over. Anti-EU MPs were making a grave mistake, he argued, if they believed that parliament and the British people would just accept any deal that Theresa May could extract. Leavers needed to mobilise for the cause.

“There is no Leave campaign,” Farage said. “I think Leave is in danger of not even making the argument.” He added: “I feel like I did 20 years ago when it looked like we were heading into the euro. We had to set up Business for Sterling to stop it.” Things felt eerily familiar now. “The Remain side is making all the running. They have a majority in parliament and unless we get ourselves organised we could lose the historic victory that was Brexit.”

With the clock ticking, and with parliament having voted to trigger the article 50 process that puts the UK on the legal track to leave the EU on 29 March next year, it is still extremely difficult to see how the Brexit train can be derailed entirely.

But Farage’s interventions over recent days are highly significant, and about far more than the rogueish populist yearning to be back in the headlines. He is nothing if not a shrewd interpreter of prevailing political and public moods. “He is dangerous – and brilliant, in equal measure,” says one ardent Tory MP from the Remain side. “We know that from painful experience.”

Farage fears a very soft Brexit as much as no Brexit at all. And he is not alone in spotting that the forces favouring soft Brexit – in Westminster at least – are now in the ascendancy. It is not just pro-Remain Labour MPs who are marshalling their troops to great effect to demand that their party and parliament as a whole backs as close a relationship as possible with the EU after March next year.

Where John Major and David Cameron had rightwing Eurosceptic rebels to deal with, May, with no Commons majority, now finds her biggest problems coming from those on the pro-EU left flank of the Tory party. Her chaotic reshuffle last week added new recruits to that ever more confident rebel army, among them sacked education secretary and Remainer Justine Greening.

At prime minister’s questions last Wednesday, the day after she left the cabinet, Greening arrived early. When anti-Brexit Tory rebel Dominic Grieve came into the chamber, Greening caught his eye and patted on the vacant seat by her side in a gesture that invited him to be her new neighbour in the naughty soft Brexit corner. Grieve duly accepted.

“It was a fantastic moment for us,” said another in the group, who added that May had made a big mistake ousting the MP for Putney from the cabinet. “A Remainer, from Rotherham, educated at a state school. Who just happens to be in a same sex relationship. How many bloody boxes does she tick for us? For too long this party has been run by a few rightwingers intent on destroying our country. Now we are taking the party back.”

Ryan Shorthouse, director of the modernising Tory pressure group, Bright Blue, said: “Before Theresa May became prime minister, for decades Conservative governments only really faced concerted pressure on the backbenchers from the right of the party. Now, there is a group of high-profile and senior backbenchers on the ‘one nation’ wing who are increasingly co-ordinated, empowered and outspoken.”

This week will be another crucial one in the parliamentary battle on Brexit, over which Farage is agonising. The EU withdrawal bill will complete its third reading and report stage in the Commons on Wednesday before heading to the House of Lords, where it faces a mauling, not least from dozens of pro-Remain peers who favour a second referendum.

Before Christmas, Grieve, a former attorney general, led a successful Tory rebellion against hard Brexit to ensure MPs will have to vote for a new statute before any Brexit deal can be agreed. The effect is to give MPs a vote – and an effective veto, on the outcome of negotiations with Brussels – something the hard Brexiters were determined to resist.

This week the focus will be on Labour, as a growing number of Jeremy Corbyn’s MPs put pressure on their leader to adopt a firmer pro-EU, pro-single market line. Upwards of 60 Labour MPs are now believed to back permanent membership of the single market and customs union after Brexit and are ready to rebel.

Labour has already come a long way down the soft Brexit road – but not far enough for dozens of its MPs. Last summer, shadow Brexit secretary Keir Starmer shifted to support membership of the single market and customs union during a post-Brexit transition of up to four years.

He is now being urged to go much further. This weekend, in a sign of that pressure, the leadership announced it would back an amendment tabled by former shadow Scottish secretary Ian Murray, which he drew up in the belief it would leave the party effectively backing single-market membership for the long term.

The amendment says that, after the final Brexit deal is done and known, Labour will insist on a full independent economic analysis, involving the National Audit Office, the Office of Budget Responsibility, the government actuary’s department, and the finance directorates of each of the devolved administrations, before MPs vote on the final deal.

Chuka Umunna, one of the Labour MPs leading cross-party efforts to secure a soft Brexit, sees this as a step forward, though still an insufficient one.

“This is a significant move, which shows we are rightly focusing on the need to demonstrate what the economic impact of Theresa May’s Tory Brexit will be on people’s lives.

“If such an assessment is not carried out, or if it is and concludes that a Tory Brexit deal would be bad for the economy, we should oppose it. Labour should be clear that at a minimum we should back single market and customs union membership (or full participation) for good.” Meanwhile peers – including many who take the Tory whip – are joining cross-party alliances in an attempt to secure long-term single-market and customs membership.

Some are also planning amendments calling for a second referendum before the UK leaves the EU – the same suggestion as that made by Farage on Tuesday.

On Saturday it emerged that, following Farage’s meeting with Barnier in Brussels last week, it will be the turn of Tory Remainers Grieve and Anna Soubry and Labour MPs Leslie, Umunna and Stephen Doughty to bend the ear of the man leading the EU negotiations on Brexit.

Their meeting with Barnier will be another blow to Farage – and further confirmation of his growing conviction that victory for Leave on the night of 23 June 2016 was far from the end of the story.

When Nigel Farage emerged from a meeting in Brussels with the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier shortly after midday last Monday his increasingly gloomy mood had darkened further. “The message I got was that they will be happy to trade chocolate and cheese and wine freely with us but when it comes to services, forget it. It ain’t going to happen. I think we are going to have a very bad deal.”

In the early hours of 24 June, 2016, the former Ukip leader, who had, arguably, done more than anyone to deliver the Leave vote, toured TV stations, triumphantly hailing the UK’s “independence day”. In Farage’s view it was not only a defining moment for Britain. It was also one that would demonstrate to other EU member states with strong or emerging eurosceptic movements – he cited Denmark, Italy, Sweden and Austria – that there was another way. “The EU is failing, the EU is dying. I hope that we have knocked the first brick out of the wall,” he declared in the glow of victory.

Nineteen months on, that joy and optimism have been replaced by doubt and fear. These days Farage is a genuinely worried man. He deeply regrets that the Leave campaign effectively “shut up shop” the day after the referendum, believing it was job done. The result of doing so, he told the Observer on Friday, was that the Leave side is now being seriously outgunned by well-funded, well-organised supporters of Remain who are intent on overturning the referendum result.

Three days after his meeting with Barnier, Farage went on TV again and said he was coming round to the view that a second referendum might be the only way to regain the initiative, to cement Brexit and shut down the issue for a generation. He said then that he thought Leave would win again, and by a bigger margin.

But on Friday he was less sure – and revealed the real depth and root of his anxieties. The momentum, he made clear, was running away from the Leavers. They had vacated the field for Remain to run all over. Anti-EU MPs were making a grave mistake, he argued, if they believed that parliament and the British people would just accept any deal that Theresa May could extract. Leavers needed to mobilise for the cause.

“There is no Leave campaign,” Farage said. “I think Leave is in danger of not even making the argument.” He added: “I feel like I did 20 years ago when it looked like we were heading into the euro. We had to set up Business for Sterling to stop it.” Things felt eerily familiar now. “The Remain side is making all the running. They have a majority in parliament and unless we get ourselves organised we could lose the historic victory that was Brexit.”

With the clock ticking, and with parliament having voted to trigger the article 50 process that puts the UK on the legal track to leave the EU on 29 March next year, it is still extremely difficult to see how the Brexit train can be derailed entirely.

But Farage’s interventions over recent days are highly significant, and about far more than the rogueish populist yearning to be back in the headlines. He is nothing if not a shrewd interpreter of prevailing political and public moods. “He is dangerous – and brilliant, in equal measure,” says one ardent Tory MP from the Remain side. “We know that from painful experience.”

Farage fears a very soft Brexit as much as no Brexit at all. And he is not alone in spotting that the forces favouring soft Brexit – in Westminster at least – are now in the ascendancy. It is not just pro-Remain Labour MPs who are marshalling their troops to great effect to demand that their party and parliament as a whole backs as close a relationship as possible with the EU after March next year.

Where John Major and David Cameron had rightwing Eurosceptic rebels to deal with, May, with no Commons majority, now finds her biggest problems coming from those on the pro-EU left flank of the Tory party. Her chaotic reshuffle last week added new recruits to that ever more confident rebel army, among them sacked education secretary and Remainer Justine Greening.

At prime minister’s questions last Wednesday, the day after she left the cabinet, Greening arrived early. When anti-Brexit Tory rebel Dominic Grieve came into the chamber, Greening caught his eye and patted on the vacant seat by her side in a gesture that invited him to be her new neighbour in the naughty soft Brexit corner. Grieve duly accepted.

“It was a fantastic moment for us,” said another in the group, who added that May had made a big mistake ousting the MP for Putney from the cabinet. “A Remainer, from Rotherham, educated at a state school. Who just happens to be in a same sex relationship. How many bloody boxes does she tick for us? For too long this party has been run by a few rightwingers intent on destroying our country. Now we are taking the party back.”

Ryan Shorthouse, director of the modernising Tory pressure group, Bright Blue, said: “Before Theresa May became prime minister, for decades Conservative governments only really faced concerted pressure on the backbenchers from the right of the party. Now, there is a group of high-profile and senior backbenchers on the ‘one nation’ wing who are increasingly co-ordinated, empowered and outspoken.”

This week will be another crucial one in the parliamentary battle on Brexit, over which Farage is agonising. The EU withdrawal bill will complete its third reading and report stage in the Commons on Wednesday before heading to the House of Lords, where it faces a mauling, not least from dozens of pro-Remain peers who favour a second referendum.

Before Christmas, Grieve, a former attorney general, led a successful Tory rebellion against hard Brexit to ensure MPs will have to vote for a new statute before any Brexit deal can be agreed. The effect is to give MPs a vote – and an effective veto, on the outcome of negotiations with Brussels – something the hard Brexiters were determined to resist.

This week the focus will be on Labour, as a growing number of Jeremy Corbyn’s MPs put pressure on their leader to adopt a firmer pro-EU, pro-single market line. Upwards of 60 Labour MPs are now believed to back permanent membership of the single market and customs union after Brexit and are ready to rebel.

Labour has already come a long way down the soft Brexit road – but not far enough for dozens of its MPs. Last summer, shadow Brexit secretary Keir Starmer shifted to support membership of the single market and customs union during a post-Brexit transition of up to four years.

He is now being urged to go much further. This weekend, in a sign of that pressure, the leadership announced it would back an amendment tabled by former shadow Scottish secretary Ian Murray, which he drew up in the belief it would leave the party effectively backing single-market membership for the long term.

The amendment says that, after the final Brexit deal is done and known, Labour will insist on a full independent economic analysis, involving the National Audit Office, the Office of Budget Responsibility, the government actuary’s department, and the finance directorates of each of the devolved administrations, before MPs vote on the final deal.

Chuka Umunna, one of the Labour MPs leading cross-party efforts to secure a soft Brexit, sees this as a step forward, though still an insufficient one.

“This is a significant move, which shows we are rightly focusing on the need to demonstrate what the economic impact of Theresa May’s Tory Brexit will be on people’s lives.

“If such an assessment is not carried out, or if it is and concludes that a Tory Brexit deal would be bad for the economy, we should oppose it. Labour should be clear that at a minimum we should back single market and customs union membership (or full participation) for good.” Meanwhile peers – including many who take the Tory whip – are joining cross-party alliances in an attempt to secure long-term single-market and customs membership.

Some are also planning amendments calling for a second referendum before the UK leaves the EU – the same suggestion as that made by Farage on Tuesday.

On Saturday it emerged that, following Farage’s meeting with Barnier in Brussels last week, it will be the turn of Tory Remainers Grieve and Anna Soubry and Labour MPs Leslie, Umunna and Stephen Doughty to bend the ear of the man leading the EU negotiations on Brexit.

Their meeting with Barnier will be another blow to Farage – and further confirmation of his growing conviction that victory for Leave on the night of 23 June 2016 was far from the end of the story.

Wednesday, 20 December 2017

May can berate Putin. But Brexit is his dream policy

As the Russian leader tries to diminish Europe, he finds ideologues such as Boris Johnson are doing the job for him

Rafael Behr in The Guardian

With lighter diplomatic baggage, Boris Johnson might have been a hit in Moscow. The foreign secretary’s artfully dishevelled, pseudo-Churchillian kitsch is not to everyone’s taste, but it could work in the bombastic idiom of Russian politics.

But as Theresa May’s emissary to the court of Vladimir Putin later this week, Johnson faces a tough audience. May has accused the Kremlin of aggressively targeting an international order based on law, open economies and free societies. In a speech last month, the prime minister listed offences including territorial theft from Ukraine, cyber-attacks on ministries and parliaments, meddling in elections, and spreading fake news to sow discord.

Russian interference in British democracy is currently being investigated by the Electoral Commission and parliament’s culture, media and sports committee. The latter’s chair, Tory MP Damian Collins, has signalled that he doesn’t believe recent claims by Twitter and Facebook that Kremlin-funded efforts to boost Brexit in 2016 were negligible.

He is right to be sceptical. The tech companies have a record of stonewalling any suggestion that their business model has been co-opted for organised malfeasance. They have commercial incentives to duck moral responsibility for the sinister content shared on their networks. It is beyond doubt that Donald Trump’s presidential campaign had a hefty Russian boost. Facebook has removed tens of thousands of pages believed to be involved in sabotage of French and German elections. British ballots are unlikely to have escaped dirty money and molestation by troll battalions.

That doesn’t mean Brexit is a conspiracy that blew in on the east wind. Mistrust of the EU was not made in a factory outside St Petersburg. To connect tweets in Murmansk to a leave majority in Merthyr Tydfil misses the point about misinformation. The goal is not always to execute a specific outcome but to stoke existing tensions, nurture rage, exacerbate polarisation and shroud everything in such a fog of lies that truth becomes ungraspable. The purpose of fake news is to debase the currency of all news, and so undermine the foundations of pluralistic politics.

The advantage to Russia is in weakening western governments and their alliances. Putin despises Nato and EU influence in countries that were, until 1991, Soviet territory. He sees their sovereignty as fictions imposed by enemies. Undermining European and US resolve to uphold their borders is his goal.

There is a strain of Brexitism that is complicit in that project, regardless of whether leave campaigns knowingly or unwittingly took laundered roubles. Nigel Farage’s admiration for Putin is no secret: he has pushed the Kremlin line on Ukraine, preposterously depicting Crimea’s annexation as a defensive answer to EU provocation. He has described Russian military support for Syria’s murderous president Bashar al-Assad as a “brilliant” manoeuvre.

Putinophilia has the same cause as Farage’s Trump fandom. It is the nationalist’s fetish for a strongman, combined with nostalgia for the days when the world was run as a game between big countries using little countries as chips. It is unresolved grief at the UK’s 20th-century relegation from the ranks of imperial pawn-pushers.

That slow-burn trauma is analogous to the more sudden loss of status mourned by Russia, the reversal of which is Putin’s mission in life. During the cold war, British ideologues who swallowed a Kremlin agenda and regurgitated it as their own used to be called “useful idiots”. The difference now is they aren’t confined to the far left. Some of them are in government.

We may never know how much influence the Kremlin had in the referendum, but we can be sure its result was popular there

The Brexit delusion is that enslavement by Brussels inhibits our promotion back to the global power premier league. Boris Johnson is not immune to this fantasy. He would rather be a foreign secretary in the 19th-century style of Lord Castlereagh, carving out spheres of influence at the Congress of Vienna, than yawn through EU council meetings.

It is true that the EU empowers smaller countries. Witness the clout that Ireland has had in Brexit talks. But Britain has also benefited from aggregating its medium-sized might with Germany, France and 25 other nations. That is not a Brussels empire. It is a model of peaceful, collaborative power without historical equal.

May once understood this. In the referendum campaign she made a solid case for EU membership on the grounds that it could “maximise Britain’s security, prosperity and influence in the world”. When she now promises a “deep and special partnership”, she is not just talking about trade, she is pledging loyalty to European democracy as one of its few significant military underwriters. When the prime minister berates Putin for undermining institutions that uphold the rule of law, she is signalling strategic solidarity, not economic alignment, with the EU.

This is chasing a bolting horse when the stable door hangs off its hinges. We may never know how much influence the Kremlin had in the referendum, but we can be sure its result was popular there. Brexit has already fractured an alliance that will be hard to repair. May will never be a friend of Putin, but he doesn’t need her friendship when she is committed to a policy he would choose for her anyway.

Rafael Behr in The Guardian

With lighter diplomatic baggage, Boris Johnson might have been a hit in Moscow. The foreign secretary’s artfully dishevelled, pseudo-Churchillian kitsch is not to everyone’s taste, but it could work in the bombastic idiom of Russian politics.

But as Theresa May’s emissary to the court of Vladimir Putin later this week, Johnson faces a tough audience. May has accused the Kremlin of aggressively targeting an international order based on law, open economies and free societies. In a speech last month, the prime minister listed offences including territorial theft from Ukraine, cyber-attacks on ministries and parliaments, meddling in elections, and spreading fake news to sow discord.

Russian interference in British democracy is currently being investigated by the Electoral Commission and parliament’s culture, media and sports committee. The latter’s chair, Tory MP Damian Collins, has signalled that he doesn’t believe recent claims by Twitter and Facebook that Kremlin-funded efforts to boost Brexit in 2016 were negligible.

He is right to be sceptical. The tech companies have a record of stonewalling any suggestion that their business model has been co-opted for organised malfeasance. They have commercial incentives to duck moral responsibility for the sinister content shared on their networks. It is beyond doubt that Donald Trump’s presidential campaign had a hefty Russian boost. Facebook has removed tens of thousands of pages believed to be involved in sabotage of French and German elections. British ballots are unlikely to have escaped dirty money and molestation by troll battalions.

That doesn’t mean Brexit is a conspiracy that blew in on the east wind. Mistrust of the EU was not made in a factory outside St Petersburg. To connect tweets in Murmansk to a leave majority in Merthyr Tydfil misses the point about misinformation. The goal is not always to execute a specific outcome but to stoke existing tensions, nurture rage, exacerbate polarisation and shroud everything in such a fog of lies that truth becomes ungraspable. The purpose of fake news is to debase the currency of all news, and so undermine the foundations of pluralistic politics.

The advantage to Russia is in weakening western governments and their alliances. Putin despises Nato and EU influence in countries that were, until 1991, Soviet territory. He sees their sovereignty as fictions imposed by enemies. Undermining European and US resolve to uphold their borders is his goal.

There is a strain of Brexitism that is complicit in that project, regardless of whether leave campaigns knowingly or unwittingly took laundered roubles. Nigel Farage’s admiration for Putin is no secret: he has pushed the Kremlin line on Ukraine, preposterously depicting Crimea’s annexation as a defensive answer to EU provocation. He has described Russian military support for Syria’s murderous president Bashar al-Assad as a “brilliant” manoeuvre.

Putinophilia has the same cause as Farage’s Trump fandom. It is the nationalist’s fetish for a strongman, combined with nostalgia for the days when the world was run as a game between big countries using little countries as chips. It is unresolved grief at the UK’s 20th-century relegation from the ranks of imperial pawn-pushers.

That slow-burn trauma is analogous to the more sudden loss of status mourned by Russia, the reversal of which is Putin’s mission in life. During the cold war, British ideologues who swallowed a Kremlin agenda and regurgitated it as their own used to be called “useful idiots”. The difference now is they aren’t confined to the far left. Some of them are in government.

We may never know how much influence the Kremlin had in the referendum, but we can be sure its result was popular there

The Brexit delusion is that enslavement by Brussels inhibits our promotion back to the global power premier league. Boris Johnson is not immune to this fantasy. He would rather be a foreign secretary in the 19th-century style of Lord Castlereagh, carving out spheres of influence at the Congress of Vienna, than yawn through EU council meetings.

It is true that the EU empowers smaller countries. Witness the clout that Ireland has had in Brexit talks. But Britain has also benefited from aggregating its medium-sized might with Germany, France and 25 other nations. That is not a Brussels empire. It is a model of peaceful, collaborative power without historical equal.

May once understood this. In the referendum campaign she made a solid case for EU membership on the grounds that it could “maximise Britain’s security, prosperity and influence in the world”. When she now promises a “deep and special partnership”, she is not just talking about trade, she is pledging loyalty to European democracy as one of its few significant military underwriters. When the prime minister berates Putin for undermining institutions that uphold the rule of law, she is signalling strategic solidarity, not economic alignment, with the EU.

This is chasing a bolting horse when the stable door hangs off its hinges. We may never know how much influence the Kremlin had in the referendum, but we can be sure its result was popular there. Brexit has already fractured an alliance that will be hard to repair. May will never be a friend of Putin, but he doesn’t need her friendship when she is committed to a policy he would choose for her anyway.

Monday, 8 May 2017

The great British Brexit robbery: how our democracy was hijacked

by Carole Cadwalladr in The Guardian

“The connectivity that is the heart of globalisation can be exploited by states with hostile intent to further their aims.[…] The risks at stake are profound and represent a fundamental threat to our sovereignty.”

Alex Younger, head of MI6, December, 2016

Alex Younger, head of MI6, December, 2016

“It’s not MI6’s job to warn of internal threats. It was a very strange speech. Was it one branch of the intelligence services sending a shot across the bows of another? Or was it pointed at Theresa May’s government? Does she know something she’s not telling us?”

Senior intelligence analyst, April 2017

Senior intelligence analyst, April 2017

In June 2013, a young American postgraduate called Sophie was passing through London when she called up the boss of a firm where she’d previously interned. The company, SCL Elections, went on to be bought by Robert Mercer, a secretive hedge fund billionaire, renamed Cambridge Analytica, and achieved a certain notoriety as the data analytics firm that played a role in both Trump and Brexit campaigns. But all of this was still to come. London in 2013 was still basking in the afterglow of the Olympics. Britain had not yet Brexited. The world had not yet turned.

“That was before we became this dark, dystopian data company that gave the world Trump,” a former Cambridge Analytica employee who I’ll call Paul tells me. “It was back when we were still just a psychological warfare firm.”

Was that really what you called it, I ask him. Psychological warfare? “Totally. That’s what it is. Psyops. Psychological operations – the same methods the military use to effect mass sentiment change. It’s what they mean by winning ‘hearts and minds’. We were just doing it to win elections in the kind of developing countries that don’t have many rules.”

Why would anyone want to intern with a psychological warfare firm, I ask him. And he looks at me like I am mad. “It was like working for MI6. Only it’s MI6 for hire. It was very posh, very English, run by an old Etonian and you got to do some really cool things. Fly all over the world. You were working with the president of Kenya or Ghana or wherever. It’s not like election campaigns in the west. You got to do all sorts of crazy shit.”

On that day in June 2013, Sophie met up with SCL’s chief executive, Alexander Nix, and gave him the germ of an idea. “She said, ‘You really need to get into data.’ She really drummed it home to Alexander. And she suggested he meet this firm that belonged to someone she knew about through her father.”

Who’s her father?

“Eric Schmidt.”

Eric Schmidt – the chairman of Google?

“Yes. And she suggested Alexander should meet this company called Palantir.”

I had been speaking to former employees of Cambridge Analytica for months and heard dozens of hair-raising stories, but it was still a gobsmacking moment. To anyone concerned about surveillance, Palantir is practically now a trigger word. The data-mining firm has contracts with governments all over the world – including GCHQ and the NSA. It’s owned by Peter Thiel, the billionaire co-founder of eBay and PayPal, who became Silicon Valley’s first vocal supporter of Trump.

In some ways, Eric Schmidt’s daughter showing up to make an introduction to Palantir is just another weird detail in the weirdest story I have ever researched.

A weird but telling detail. Because it goes to the heart of why the story of Cambridge Analytica is one of the most profoundly unsettling of our time. Sophie Schmidt now works for another Silicon Valley megafirm: Uber. And what’s clear is that the power and dominance of the Silicon Valley – Google and Facebook and a small handful of others – are at the centre of the global tectonic shift we are currently witnessing.

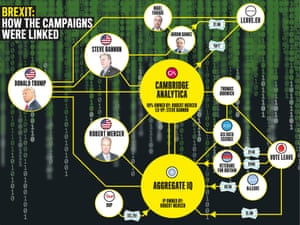

The money man: Robert Mercer, Trump supporter and owner of Cambridge Analytica. Photograph: Rex

It also reveals a critical and gaping hole in the political debate in Britain. Because what is happening in America and what is happening in Britain are entwined. Brexit and Trump are entwined. The Trump administration’s links to Russia and Britain are entwined. And Cambridge Analytica is one point of focus through which we can see all these relationships in play; it also reveals the elephant in the room as we hurtle into a general election: Britain tying its future to an America that is being remade - in a radical and alarming way - by Trump.

There are three strands to this story. How the foundations of an authoritarian surveillance state are being laid in the US. How British democracy was subverted through a covert, far-reaching plan of coordination enabled by a US billionaire. And how we are in the midst of a massive land grab for power by billionaires via our data. Data which is being silently amassed, harvested and stored. Whoever owns this data owns the future.

My entry point into this story began, as so many things do, with a late-night Google. Last December, I took an unsettling tumble into a wormhole of Google autocompletesuggestions that ended with “did the holocaust happen”. And an entire page of results that claimed it didn’t.

Google’s algorithm had been gamed by extremist sites and it was Jonathan Albright, a professor of communications at Elon University, North Carolina, who helped me get to grips with what I was seeing. He was the first person to map and uncover an entire “alt-right” news and information ecosystem and he was the one who first introduced me to Cambridge Analytica.

He called the company a central point in the right’s “propaganda machine”, a line I quoted in reference to its work for the Trump election campaign and the referendum Leave campaign. That led to the second article featuring Cambridge Analytica – as a central node in the alternative news and information network that I believed Robert Mercer and Steve Bannon, the key Trump aide who is now his chief strategist, were creating. I found evidence suggesting they were on a strategic mission to smash the mainstream media and replace it with one comprising alternative facts, fake history and rightwing propaganda.

Mercer is a brilliant computer scientist, a pioneer in early artificial intelligence, and the co-owner of one of the most successful hedge funds on the planet (with a gravity-defying 71.8% annual return). And, he is also, I discovered, good friends with Nigel Farage. Andy Wigmore, Leave.EU’s communications director, told me that it was Mercer who had directed his company, Cambridge Analytica, to “help” the Leave campaign.

The second article triggered two investigations, which are both continuing: one by the Information Commissioner’s Office into the possible illegal use of data. And a second by the Electoral Commission which is “focused on whether one or more donations – including services – accepted by Leave.EU was ‘impermissable’”.

What I then discovered is that Mercer’s role in the referendum went far beyond this. Far beyond the jurisdiction of any UK law. The key to understanding how a motivated and determined billionaire could bypass ourelectoral laws rests on AggregateIQ, an obscure web analytics company based in an office above a shop in Victoria, British Columbia.

It was with AggregateIQ that Vote Leave (the official Leave campaign) chose to spend £3.9m, more than half its official £7m campaign budget. As did three other affiliated Leave campaigns: BeLeave, Veterans for Britain and the Democratic Unionist party, spending a further £757,750. “Coordination” between campaigns is prohibited under UK electoral law, unless campaign expenditure is declared, jointly. It wasn’t. Vote Leave says the Electoral Commission “looked into this” and gave it “a clean bill of health”.

How did an obscure Canadian company come to play such a pivotal role in Brexit? It’s a question that Martin Moore, director of the centre for the study of communication, media and power at King’s College London has been asking too. “I went through all the Leave campaign invoices when the Electoral Commission uploaded them to its site in February. And I kept on discovering all these huge amounts going to a company that not only had I never heard of, but that there was practically nothing at all about on the internet. More money was spent with AggregateIQ than with any other company in any other campaign in the entire referendum. All I found, at that time, was a one-page website and that was it. It was an absolute mystery.”

Moore contributed to an LSE report published in April that concluded UK’s electoral laws were “weak and helpless” in the face of new forms of digital campaigning. Offshore companies, money poured into databases, unfettered third parties… the caps on spending had come off. The laws that had always underpinned Britain’s electoral laws were no longer fit for purpose. Laws, the report said, that needed “urgently reviewing by parliament”.

AggregateIQ holds the key to unravelling another complicated network of influence that Mercer has created. A source emailed me to say he had found that AggregateIQ’s address and telephone number corresponded to a company listed on Cambridge Analytica’s website as its overseas office: “SCL Canada”. A day later, that online reference vanished.

There had to be a connection between the two companies. Between the various Leave campaigns. Between the referendum and Mercer. It was too big a coincidence. But everyone – AggregateIQ, Cambridge Analytica, Leave.EU, Vote Leave – denied it. AggregateIQ had just been a short-term “contractor” to Cambridge Analytica. There was nothing to disprove this. We published the known facts. On 29 March, article 50 was triggered.

Then I meet Paul, the first of two sources formerly employed by Cambridge Analytica. He is in his late 20s and bears mental scars from his time there. “It’s almost like post-traumatic shock. It was so… messed up. It happened so fast. I just woke up one morning and found we’d turned into the Republican fascist party. I still can’t get my head around it.”

He laughed when I told him the frustrating mystery that was AggregateIQ. “Find Chris Wylie,” he said.

Who’s Chris Wylie?

“He’s the one who brought data and micro-targeting [individualised political messages] to Cambridge Analytica. And he’s from west Canada. It’s only because of him that AggregateIQ exist. They’re his friends. He’s the one who brought them in.”

There wasn’t just a relationship between Cambridge Analytica and AggregateIQ, Paul told me. They were intimately entwined, key nodes in Robert Mercer’s distributed empire. “The Canadians were our back office. They built our software for us. They held our database. If AggregateIQ is involved then Cambridge Analytica is involved. And if Cambridge Analytica is involved, then Robert Mercer and Steve Bannon are involved. You need to find Chris Wylie.”

I did find Chris Wylie. He refused to comment.

Key to understanding how data would transform the company is knowing where it came from. And it’s a letter from “Director of Defence Operations, SCL Group”, that helped me realise this. It’s from “Commander Steve Tatham, PhD, MPhil, Royal Navy (rtd)” complaining about my use in my Mercer article of the word “disinformation”.

I wrote back to him pointing out references in papers he’d written to “deception” and “propaganda”, which I said I understood to be “roughly synonymous with ‘disinformation’.” It’s only later that it strikes me how strange it is that I’m corresponding with a retired navy commander about military strategies that may have been used in British and US elections.

What’s been lost in the US coverage of this “data analytics” firm is the understanding of where the firm came from: deep within the military-industrial complex. A weird British corner of it populated, as the military establishment in Britain is, by old-school Tories. Geoffrey Pattie, a former parliamentary under-secretary of state for defence procurement and director of Marconi Defence Systems, used to be on the board, and Lord Marland, David Cameron’s pro-Brexit former trade envoy, a shareholder.

Steve Tatham was the head of psychological operations for British forces in Afghanistan. The Observer has seen letters endorsing him from the UK Ministry of Defence, the Foreign Office and Nato.

SCL/Cambridge Analytica was not some startup created by a couple of guys with a Mac PowerBook. It’s effectively part of the British defence establishment. And, now, too, the American defence establishment. An ex-commanding officer of the US Marine Corps operations centre, Chris Naler, has recently joined Iota Global, a partner of the SCL group.

This is not just a story about social psychology and data analytics. It has to be understood in terms of a military contractor using military strategies on a civilian population. Us. David Miller, a professor of sociology at Bath University and an authority in psyops and propaganda, says it is “an extraordinary scandal that this should be anywhere near a democracy. It should be clear to voters where information is coming from, and if it’s not transparent or open where it’s coming from, it raises the question of whether we are actually living in a democracy or not.”

Paul and David, another ex-Cambridge Analytica employee, were working at the firm when it introduced mass data-harvesting to its psychological warfare techniques. “It brought psychology, propaganda and technology together in this powerful new way,” David tells me.

Steve Bannon, former vice-president of Cambridge Analytica, now a key adviser to Donald Trump. Photograph: Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

And it was Facebook that made it possible. It was from Facebook that Cambridge Analytica obtained its vast dataset in the first place. Earlier, psychologists at Cambridge University harvested Facebook data (legally) for research purposes and published pioneering peer-reviewed work about determining personality traits, political partisanship, sexuality and much more from people’s Facebook “likes”. And SCL/Cambridge Analytica contracted a scientist at the university, Dr Aleksandr Kogan, to harvest new Facebook data. And he did so by paying people to take a personality quiz which also allowed not just their own Facebook profiles to be harvested, but also those of their friends – a process then allowed by the social network.

Facebook was the source of the psychological insights that enabled Cambridge Analytica to target individuals. It was also the mechanism that enabled them to be delivered on a large scale.