'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label idea. Show all posts

Showing posts with label idea. Show all posts

Wednesday, 19 June 2024

Tuesday, 27 June 2023

Saturday, 18 June 2022

Wednesday, 27 January 2021

Covid lies cost lives – we have a duty to clamp down on them

George Monbiot in The Guardian

Why do we value lies more than lives? We know that certain falsehoods kill people. Some of those who believe such claims as “coronavirus doesn’t exist”, “it’s not the virus that makes people ill but 5G”, or “vaccines are used to inject us with microchips” fail to take precautions or refuse to be vaccinated, then contract and spread the virus. Yet we allow these lies to proliferate.

We have a right to speak freely. We also have a right to life. When malicious disinformation – claims that are known to be both false and dangerous – can spread without restraint, these two values collide head-on. One of them must give way, and the one we have chosen to sacrifice is human life. We treat free speech as sacred, but life as negotiable. When governments fail to ban outright lies that endanger people’s lives, I believe they make the wrong choice.

Any control by governments of what we may say is dangerous, especially when the government, like ours, has authoritarian tendencies. But the absence of control is also dangerous. In theory, we recognise that there are necessary limits to free speech: almost everyone agrees that we should not be free to shout “fire!” in a crowded theatre, because people are likely to be trampled to death. Well, people are being trampled to death by these lies. Surely the line has been crossed?

Those who demand absolute freedom of speech often talk about “the marketplace of ideas”. But in a marketplace, you are forbidden to make false claims about your product. You cannot pass one thing off as another. You cannot sell shares on a false prospectus. You are legally prohibited from making money by lying to your customers. In other words, in the marketplace there are limits to free speech. So where, in the marketplace of ideas, are the trading standards? Who regulates the weights and measures? Who checks the prospectus? We protect money from lies more carefully than we protect human life.

I believe that spreading only the most dangerous falsehoods, like those mentioned in the first paragraph, should be prohibited. A possible template is the Cancer Act, which bans people from advertising cures or treatments for cancer. A ban on the worst Covid lies should be time-limited, running for perhaps six months. I would like to see an expert committee, similar to the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage), identifying claims that present a genuine danger to life and proposing their temporary prohibition to parliament.

While this measure would apply only to the most extreme cases, we should be far more alert to the dangers of misinformation in general. Even though it states that the pundits it names are not deliberately spreading false information, the new Anti-Virus site www.covidfaq.co might help to tip the balance against people such as Allison Pearson, Peter Hitchens and Sunetra Gupta, who have made such public headway with their misleading claims about the pandemic.

But how did these claims become so prominent? They achieved traction only because they were given a massive platform in the media, particularly in the Telegraph, the Mail and – above all – the house journal of unscientific gibberish, the Spectator. Their most influential outlet is the BBC. The BBC has an unerring instinct for misjudging where debate about a matter of science lies. It thrills to the sound of noisy, ill-informed contrarians. As the conservationist Stephen Barlow argues, science denial is destroying our societies and the survival of life on Earth. Yet it is treated by the media as a form of entertainment. The bigger the idiot, the greater the airtime.

Interestingly, all but one of the journalists mentioned on the Anti-Virus site also have a long track record of downplaying and, in some cases, denying, climate breakdown. Peter Hitchens, for example, has dismissed not only human-made global heating, but the greenhouse effect itself. Today, climate denial has mostly dissipated in this country, perhaps because the BBC has at last stopped treating climate change as a matter of controversy, and Channel 4 no longer makes films claiming that climate science is a scam. The broadcasters kept this disinformation alive, just as the BBC, still providing a platform for misleading claims this month, sustains falsehoods about the pandemic.

Ironies abound, however. One of the founders of the admirable Anti-Virus site is Sam Bowman, a senior fellow at the Adam Smith Institute (ASI). This is an opaquely funded lobby group with a long history of misleading claims about science that often seem to align with its ideology or the interests of its funders. For example, it has downplayed the dangers of tobacco smoke, and argued against smoking bans in pubs and plain packaging for cigarettes. In 2013, the Observer revealed that it had been taking money from tobacco companies. Bowman himself, echoing arguments made by the tobacco industry, has called for the “lifting [of] all EU-wide regulations on cigarette packaging” on the grounds of “civil liberties”. He has also railed against government funding for public health messages about the dangers of smoking.

Some of the ASI’s past claims about climate science – such as statements that the planet is “failing to warm” and that climate science is becoming “completely and utterly discredited” – are as idiotic as the claims about the pandemic that Bowman rightly exposes. The ASI’s Neoliberal Manifesto, published in 2019, maintains, among other howlers, that “fewer people are malnourished than ever before”. In reality, malnutrition has been rising since 2014. If Bowman is serious about being a defender of science, perhaps he could call out some of the falsehoods spread by his own organisation.

Lobby groups funded by plutocrats and corporations are responsible for much of the misinformation that saturates public life. The launch of the Great Barrington Declaration, for example, that champions herd immunity through mass infection with the help of discredited claims, was hosted – physically and online – by the American Institute for Economic Research. This institute has received money from the Charles Koch Foundation, and takes a wide range of anti-environmental positions.

It’s not surprising that we have an inveterate liar as prime minister: this government has emerged from a culture of rightwing misinformation, weaponised by thinktanks and lobby groups. False claims are big business: rich people and organisations will pay handsomely for others to spread them. Some of those whom the BBC used to “balance” climate scientists in its debates were professional liars paid by fossil-fuel companies.

Over the past 30 years, I have watched this business model spread like a virus through public life. Perhaps it is futile to call for a government of liars to regulate lies. But while conspiracy theorists make a killing from their false claims, we should at least name the standards that a good society would set, even if we can’t trust the current government to uphold them.

Why do we value lies more than lives? We know that certain falsehoods kill people. Some of those who believe such claims as “coronavirus doesn’t exist”, “it’s not the virus that makes people ill but 5G”, or “vaccines are used to inject us with microchips” fail to take precautions or refuse to be vaccinated, then contract and spread the virus. Yet we allow these lies to proliferate.

We have a right to speak freely. We also have a right to life. When malicious disinformation – claims that are known to be both false and dangerous – can spread without restraint, these two values collide head-on. One of them must give way, and the one we have chosen to sacrifice is human life. We treat free speech as sacred, but life as negotiable. When governments fail to ban outright lies that endanger people’s lives, I believe they make the wrong choice.

Any control by governments of what we may say is dangerous, especially when the government, like ours, has authoritarian tendencies. But the absence of control is also dangerous. In theory, we recognise that there are necessary limits to free speech: almost everyone agrees that we should not be free to shout “fire!” in a crowded theatre, because people are likely to be trampled to death. Well, people are being trampled to death by these lies. Surely the line has been crossed?

Those who demand absolute freedom of speech often talk about “the marketplace of ideas”. But in a marketplace, you are forbidden to make false claims about your product. You cannot pass one thing off as another. You cannot sell shares on a false prospectus. You are legally prohibited from making money by lying to your customers. In other words, in the marketplace there are limits to free speech. So where, in the marketplace of ideas, are the trading standards? Who regulates the weights and measures? Who checks the prospectus? We protect money from lies more carefully than we protect human life.

I believe that spreading only the most dangerous falsehoods, like those mentioned in the first paragraph, should be prohibited. A possible template is the Cancer Act, which bans people from advertising cures or treatments for cancer. A ban on the worst Covid lies should be time-limited, running for perhaps six months. I would like to see an expert committee, similar to the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage), identifying claims that present a genuine danger to life and proposing their temporary prohibition to parliament.

While this measure would apply only to the most extreme cases, we should be far more alert to the dangers of misinformation in general. Even though it states that the pundits it names are not deliberately spreading false information, the new Anti-Virus site www.covidfaq.co might help to tip the balance against people such as Allison Pearson, Peter Hitchens and Sunetra Gupta, who have made such public headway with their misleading claims about the pandemic.

But how did these claims become so prominent? They achieved traction only because they were given a massive platform in the media, particularly in the Telegraph, the Mail and – above all – the house journal of unscientific gibberish, the Spectator. Their most influential outlet is the BBC. The BBC has an unerring instinct for misjudging where debate about a matter of science lies. It thrills to the sound of noisy, ill-informed contrarians. As the conservationist Stephen Barlow argues, science denial is destroying our societies and the survival of life on Earth. Yet it is treated by the media as a form of entertainment. The bigger the idiot, the greater the airtime.

Interestingly, all but one of the journalists mentioned on the Anti-Virus site also have a long track record of downplaying and, in some cases, denying, climate breakdown. Peter Hitchens, for example, has dismissed not only human-made global heating, but the greenhouse effect itself. Today, climate denial has mostly dissipated in this country, perhaps because the BBC has at last stopped treating climate change as a matter of controversy, and Channel 4 no longer makes films claiming that climate science is a scam. The broadcasters kept this disinformation alive, just as the BBC, still providing a platform for misleading claims this month, sustains falsehoods about the pandemic.

Ironies abound, however. One of the founders of the admirable Anti-Virus site is Sam Bowman, a senior fellow at the Adam Smith Institute (ASI). This is an opaquely funded lobby group with a long history of misleading claims about science that often seem to align with its ideology or the interests of its funders. For example, it has downplayed the dangers of tobacco smoke, and argued against smoking bans in pubs and plain packaging for cigarettes. In 2013, the Observer revealed that it had been taking money from tobacco companies. Bowman himself, echoing arguments made by the tobacco industry, has called for the “lifting [of] all EU-wide regulations on cigarette packaging” on the grounds of “civil liberties”. He has also railed against government funding for public health messages about the dangers of smoking.

Some of the ASI’s past claims about climate science – such as statements that the planet is “failing to warm” and that climate science is becoming “completely and utterly discredited” – are as idiotic as the claims about the pandemic that Bowman rightly exposes. The ASI’s Neoliberal Manifesto, published in 2019, maintains, among other howlers, that “fewer people are malnourished than ever before”. In reality, malnutrition has been rising since 2014. If Bowman is serious about being a defender of science, perhaps he could call out some of the falsehoods spread by his own organisation.

Lobby groups funded by plutocrats and corporations are responsible for much of the misinformation that saturates public life. The launch of the Great Barrington Declaration, for example, that champions herd immunity through mass infection with the help of discredited claims, was hosted – physically and online – by the American Institute for Economic Research. This institute has received money from the Charles Koch Foundation, and takes a wide range of anti-environmental positions.

It’s not surprising that we have an inveterate liar as prime minister: this government has emerged from a culture of rightwing misinformation, weaponised by thinktanks and lobby groups. False claims are big business: rich people and organisations will pay handsomely for others to spread them. Some of those whom the BBC used to “balance” climate scientists in its debates were professional liars paid by fossil-fuel companies.

Over the past 30 years, I have watched this business model spread like a virus through public life. Perhaps it is futile to call for a government of liars to regulate lies. But while conspiracy theorists make a killing from their false claims, we should at least name the standards that a good society would set, even if we can’t trust the current government to uphold them.

Sunday, 10 January 2021

Tuesday, 28 June 2016

Why bad ideas refuse to die

Steven Poole in The Guardian

In January 2016, the rapper BoB took to Twitter to tell his fans that the Earth is really flat. “A lot of people are turned off by the phrase ‘flat earth’,” he acknowledged, “but there’s no way u can see all the evidence and not know … grow up.” At length the astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson joined in the conversation, offering friendly corrections to BoB’s zany proofs of non-globism, and finishing with a sarcastic compliment: “Being five centuries regressed in your reasoning doesn’t mean we all can’t still like your music.”

Actually, it’s a lot more than five centuries regressed. Contrary to what we often hear, people didn’t think the Earth was flat right up until Columbus sailed to the Americas. In ancient Greece, the philosophers Pythagoras and Parmenides had already recognised that the Earth was spherical. Aristotle pointed out that you could see some stars in Egypt and Cyprus that were not visible at more northerly latitudes, and also that the Earth casts a curved shadow on the moon during a lunar eclipse. The Earth, he concluded with impeccable logic, must be round.

The flat-Earth view was dismissed as simply ridiculous – until very recently, with the resurgence of apparently serious flat-Earthism on the internet. An American named Mark Sargent, formerly a professional videogamer and software consultant, has had millions of views on YouTube for his Flat Earth Clues video series. (“You are living inside a giant enclosed system,” his website warns.) The Flat Earth Society is alive and well, with a thriving website. What is going on?

Many ideas have been brilliantly upgraded or repurposed for the modern age, and their revival seems newly compelling. Some ideas from the past, on the other hand, are just dead wrong and really should have been left to rot. When they reappear, what is rediscovered is a shambling corpse. These are zombie ideas. You can try to kill them, but they just won’t die. And their existence is a big problem for our normal assumptions about how the marketplace of ideas operates.

The phrase “marketplace of ideas” was originally used as a way of defending free speech. Just as traders and customers are free to buy and sell wares in the market, so freedom of speech ensures that people are free to exchange ideas, test them out, and see which ones rise to the top. Just as good consumer products succeed and bad ones fail, so in the marketplace of ideas the truth will win out, and error and dishonesty will disappear.

There is certainly some truth in the thought that competition between ideas is necessary for the advancement of our understanding. But the belief that the best ideas will always succeed is rather like the faith that unregulated financial markets will always produce the best economic outcomes. As the IMF chief Christine Lagarde put this standard wisdom laconically in Davos: “The market sorts things out, eventually.” Maybe so. But while we wait, very bad things might happen.

Zombies don’t occur in physical marketplaces – take technology, for example. No one now buys Betamax video recorders, because that technology has been superseded and has no chance of coming back. (The reason that other old technologies, such as the manual typewriter or the acoustic piano, are still in use is that, according to the preferences of their users, they have not been superseded.) So zombies such as flat-Earthism simply shouldn’t be possible in a well‑functioning marketplace of ideas. And yet – they live. How come?

One clue is provided by economics. It turns out that the marketplace of economic ideas itself is infested with zombies. After the 2008 financial crisis had struck, the Australian economist John Quiggin published an illuminating work called Zombie Economics, describing theories that still somehow shambled around even though they were clearly dead, having been refuted by actual events in the world. An example is the notorious efficient markets hypothesis, which holds, in its strongest form, that “financial markets are the best possible guide to the value of economic assets and therefore to decisions about investment and production”. That, Quiggin argues, simply can’t be right. Not only was the efficient markets hypothesis refuted by the global meltdown of 2007–8, in Quiggin’s view it actually caused it in the first place: the idea “justified, and indeed demanded, financial deregulation, the removal of controls on international capital flows, and a massive expansion of the financial sector. These developments ultimately produced the global financial crisis.”

Even so, an idea will have a good chance of hanging around as a zombie if it benefits some influential group of people. The efficient markets hypothesis is financially beneficial for bankers who want to make deals unencumbered by regulation. A similar point can be made about the privatisation of state-owned industry: it is seldom good for citizens, but is always a cash bonanza for those directly involved.

The marketplace of ideas, indeed, often confers authority through mere repetition – in science as well as in political campaigning. You probably know, for example, that the human tongue has regional sensitivities: sweetness is sensed on the tip, saltiness and sourness on the sides, and bitter at the back. At some point you’ve seen a scientific tongue map showing this – they appear in cookery books as well as medical textbooks. It’s one of those nice, slightly surprising findings of science that no one questions. And it’s rubbish.

China’s memory manipulators

It would be sensible, for a start, for us to make the apparently trivial rhetorical adjustment from the popular phrase “studies show …” and limit ourselves to phrases such as “studies suggest” or “studies indicate”. After all, “showing” strongly implies proving, which is all too rare an activity outside mathematics. Studies can always be reconsidered. That is part of their power.

Nearly every academic inquirer I talked to while researching this subject says that the interface of research with publishing is seriously flawed. Partly because the incentives are all wrong – a “publish or perish” culture rewards academics for quantity of published research over quality. And partly because of the issue of “publication bias”: the studies that get published are the ones that have yielded hoped-for results. Studies that fail to show what they hoped for end up languishing in desk drawers.

One reform suggested by many people to counteract publication bias would be to encourage the publication of more “negative findings” – papers where a hypothesis was not backed up by the experiment performed. One problem, of course, is that such findings are not very exciting. Negative results do not make headlines. (And they sound all the duller for being called “negative findings”, rather than being framed as positive discoveries that some ideas won’t fly.)

The publication-bias issue is even more pressing in the field of medicine, where it is estimated that the results of around half of all trials conducted are never published at all, because their results are negative. “When half the evidence is withheld,” writes the medical researcher Ben Goldacre, “doctors and patients cannot make informed decisions about which treatment is best.”Accordingly, Goldacre has kickstarted a campaigning group named AllTrials to demand that all results be published.

When lives are not directly at stake, however, it might be difficult to publish more negative findings in other areas of science. One idea, floated by the Economist, is that “Journals should allocate space for ‘uninteresting’ work, and grant-givers should set aside money to pay for it.” It sounds splendid, to have a section in journals for tedious results, or maybe an entire journal dedicated to boring and perfectly unsurprising research. But good luck getting anyone to fund it.

The good news, though, is that some of the flaws in the marketplace of scientific ideas might be hidden strengths. It’s true that some people think peer review, at its glacial pace and with its bias towards the existing consensus, works to actively repress new ideas that are challenging to received opinion. Notoriously, for example, the paper that first announced the invention of graphene – a way of arranging carbon in a sheet only a single atom thick – was rejected by Nature in 2004 on the grounds that it was simply “impossible”. But that idea was too impressive to be suppressed; in fact, the authors of the graphene paper had it published in Science magazine only six months later. Most people have faith that very well-grounded results will find their way through the system. Yet it is right that doing so should be difficult. If this marketplace were more liquid and efficient, we would be overwhelmed with speculative nonsense. Even peremptory or aggressive dismissals of new findings have a crucial place in the intellectual ecology. Science would not be so robust a means of investigating the world if it eagerly embraced every shiny new idea that comes along. It has to put on a stern face and say: “Impress me.” Great ideas may well face a lot of necessary resistance, and take a long time to gain traction. And we wouldn’t wish things to be otherwise.

In many ways, then, the marketplace of ideas does not work as advertised: it is not efficient, there are frequent crashes and failures, and dangerous products often win out, to widespread surprise and dismay. It is important to rethink the notion that the best ideas reliably rise to the top: that itself is a zombie idea, which helps entrench powerful interests. Yet even zombie ideas can still be useful when they motivate energetic refutations that advance public education. Yes, we may regret that people often turn to the past to renew an old theory such as flat-Earthism, which really should have stayed dead. But some conspiracies are real, and science is always engaged in trying to uncover the hidden powers behind what we see. The resurrection of zombie ideas, as well as the stubborn rejection of promising new ones, can both be important mechanisms for the advancement of human understanding.

In January 2016, the rapper BoB took to Twitter to tell his fans that the Earth is really flat. “A lot of people are turned off by the phrase ‘flat earth’,” he acknowledged, “but there’s no way u can see all the evidence and not know … grow up.” At length the astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson joined in the conversation, offering friendly corrections to BoB’s zany proofs of non-globism, and finishing with a sarcastic compliment: “Being five centuries regressed in your reasoning doesn’t mean we all can’t still like your music.”

Actually, it’s a lot more than five centuries regressed. Contrary to what we often hear, people didn’t think the Earth was flat right up until Columbus sailed to the Americas. In ancient Greece, the philosophers Pythagoras and Parmenides had already recognised that the Earth was spherical. Aristotle pointed out that you could see some stars in Egypt and Cyprus that were not visible at more northerly latitudes, and also that the Earth casts a curved shadow on the moon during a lunar eclipse. The Earth, he concluded with impeccable logic, must be round.

The flat-Earth view was dismissed as simply ridiculous – until very recently, with the resurgence of apparently serious flat-Earthism on the internet. An American named Mark Sargent, formerly a professional videogamer and software consultant, has had millions of views on YouTube for his Flat Earth Clues video series. (“You are living inside a giant enclosed system,” his website warns.) The Flat Earth Society is alive and well, with a thriving website. What is going on?

Many ideas have been brilliantly upgraded or repurposed for the modern age, and their revival seems newly compelling. Some ideas from the past, on the other hand, are just dead wrong and really should have been left to rot. When they reappear, what is rediscovered is a shambling corpse. These are zombie ideas. You can try to kill them, but they just won’t die. And their existence is a big problem for our normal assumptions about how the marketplace of ideas operates.

The phrase “marketplace of ideas” was originally used as a way of defending free speech. Just as traders and customers are free to buy and sell wares in the market, so freedom of speech ensures that people are free to exchange ideas, test them out, and see which ones rise to the top. Just as good consumer products succeed and bad ones fail, so in the marketplace of ideas the truth will win out, and error and dishonesty will disappear.

There is certainly some truth in the thought that competition between ideas is necessary for the advancement of our understanding. But the belief that the best ideas will always succeed is rather like the faith that unregulated financial markets will always produce the best economic outcomes. As the IMF chief Christine Lagarde put this standard wisdom laconically in Davos: “The market sorts things out, eventually.” Maybe so. But while we wait, very bad things might happen.

Zombies don’t occur in physical marketplaces – take technology, for example. No one now buys Betamax video recorders, because that technology has been superseded and has no chance of coming back. (The reason that other old technologies, such as the manual typewriter or the acoustic piano, are still in use is that, according to the preferences of their users, they have not been superseded.) So zombies such as flat-Earthism simply shouldn’t be possible in a well‑functioning marketplace of ideas. And yet – they live. How come?

One clue is provided by economics. It turns out that the marketplace of economic ideas itself is infested with zombies. After the 2008 financial crisis had struck, the Australian economist John Quiggin published an illuminating work called Zombie Economics, describing theories that still somehow shambled around even though they were clearly dead, having been refuted by actual events in the world. An example is the notorious efficient markets hypothesis, which holds, in its strongest form, that “financial markets are the best possible guide to the value of economic assets and therefore to decisions about investment and production”. That, Quiggin argues, simply can’t be right. Not only was the efficient markets hypothesis refuted by the global meltdown of 2007–8, in Quiggin’s view it actually caused it in the first place: the idea “justified, and indeed demanded, financial deregulation, the removal of controls on international capital flows, and a massive expansion of the financial sector. These developments ultimately produced the global financial crisis.”

Even so, an idea will have a good chance of hanging around as a zombie if it benefits some influential group of people. The efficient markets hypothesis is financially beneficial for bankers who want to make deals unencumbered by regulation. A similar point can be made about the privatisation of state-owned industry: it is seldom good for citizens, but is always a cash bonanza for those directly involved.

The marketplace of ideas, indeed, often confers authority through mere repetition – in science as well as in political campaigning. You probably know, for example, that the human tongue has regional sensitivities: sweetness is sensed on the tip, saltiness and sourness on the sides, and bitter at the back. At some point you’ve seen a scientific tongue map showing this – they appear in cookery books as well as medical textbooks. It’s one of those nice, slightly surprising findings of science that no one questions. And it’s rubbish.

A fantasy map of a flat earth. Photograph: Antar Dayal/Getty Images/Illustration Works

As the eminent professor of biology, Stuart Firestein, explained in his 2012 book Ignorance: How it Drives Science, the tongue-map myth arose because of a mistranslation of a 1901 German physiology textbook. Regions of the tongue are just “very slightly” more or less sensitive to each of the four basic tastes, but they each can sense all of them. The translation “considerably overstated” the original author’s claims. And yet the mythical tongue map has endured for more than a century.

One of the paradoxes of zombie ideas, though, is that they can have positive social effects. The answer is not necessarily to suppress them, since even apparently vicious and disingenuous ideas can lead to illuminating rebuttal and productive research. Few would argue that a commercial marketplace needs fraud and faulty products. But in the marketplace of ideas, zombies can actually be useful. Or if not, they can at least make us feel better. That, paradoxically, is what I think the flat-Earthers of today are really offering – comfort.

Today’s rejuvenated flat-Earth philosophy, as promoted by rappers and YouTube videos, is not simply a recrudescence of pre-scientific ignorance. It is, rather, the mother of all conspiracy theories. The point is that everyone who claims the Earth is round is trying to fool you, and keep you in the dark. In that sense, it is a very modern version of an old idea.

As with any conspiracy theory, the flat-Earth idea is introduced by way of a handful of seeming anomalies, things that don’t seem to fit the “official” story. Have you ever wondered, the flat-Earther will ask, why commercial aeroplanes don’t fly over Antarctica? It would, after all, be the most direct route from South Africa to New Zealand, or from Sydney to Buenos Aires – if the Earth were round. But it isn’t. There is no such thing as the South Pole, so flying over Antarctica wouldn’t make any sense. Plus, the Antarctic treaty, signed by the world’s most powerful countries, bans any flights over it, because something very weird is going on there. So begins the conspiracy sell. Well, in fact, some commercial routes do fly over part of the continent of Antarctica. The reason none fly over the South Pole itself is because of aviation rules that require any aircraft taking such a route to have expensive survival equipment for all passengers on board – which would obviously be prohibitive for a passenger jet.

OK, the flat-Earther will say, then what about the fact that photographs taken from mountains or hot-air balloons don’t show any curvature of the horizon? It is perfectly flat – therefore the Earth must be flat. Well, a reasonable person will respond, it looks flat because the Earth, though round, is really very big. But photographs taken from the International Space Station in orbit show a very obviously curved Earth.

And here is where the conspiracy really gets going. To a flat-Earther, any photograph from the International Space Station is just a fake. So too are the famous photographs of the whole round Earth hanging in space that were taken on the Apollo missions. Of course, the Moon landings were faked too. This is a conspiracy theory that swallows other conspiracy theories whole. According to Mark Sargent’s “enclosed world” version of the flat-Earth theory, indeed, space travel had to be faked because there is actually an impermeable solid dome enclosing our flat planet. The US and USSR tried to break through this dome by nuking it in the 1950s: that’s what all those nuclear tests were really about.

As the eminent professor of biology, Stuart Firestein, explained in his 2012 book Ignorance: How it Drives Science, the tongue-map myth arose because of a mistranslation of a 1901 German physiology textbook. Regions of the tongue are just “very slightly” more or less sensitive to each of the four basic tastes, but they each can sense all of them. The translation “considerably overstated” the original author’s claims. And yet the mythical tongue map has endured for more than a century.

One of the paradoxes of zombie ideas, though, is that they can have positive social effects. The answer is not necessarily to suppress them, since even apparently vicious and disingenuous ideas can lead to illuminating rebuttal and productive research. Few would argue that a commercial marketplace needs fraud and faulty products. But in the marketplace of ideas, zombies can actually be useful. Or if not, they can at least make us feel better. That, paradoxically, is what I think the flat-Earthers of today are really offering – comfort.

Today’s rejuvenated flat-Earth philosophy, as promoted by rappers and YouTube videos, is not simply a recrudescence of pre-scientific ignorance. It is, rather, the mother of all conspiracy theories. The point is that everyone who claims the Earth is round is trying to fool you, and keep you in the dark. In that sense, it is a very modern version of an old idea.

As with any conspiracy theory, the flat-Earth idea is introduced by way of a handful of seeming anomalies, things that don’t seem to fit the “official” story. Have you ever wondered, the flat-Earther will ask, why commercial aeroplanes don’t fly over Antarctica? It would, after all, be the most direct route from South Africa to New Zealand, or from Sydney to Buenos Aires – if the Earth were round. But it isn’t. There is no such thing as the South Pole, so flying over Antarctica wouldn’t make any sense. Plus, the Antarctic treaty, signed by the world’s most powerful countries, bans any flights over it, because something very weird is going on there. So begins the conspiracy sell. Well, in fact, some commercial routes do fly over part of the continent of Antarctica. The reason none fly over the South Pole itself is because of aviation rules that require any aircraft taking such a route to have expensive survival equipment for all passengers on board – which would obviously be prohibitive for a passenger jet.

OK, the flat-Earther will say, then what about the fact that photographs taken from mountains or hot-air balloons don’t show any curvature of the horizon? It is perfectly flat – therefore the Earth must be flat. Well, a reasonable person will respond, it looks flat because the Earth, though round, is really very big. But photographs taken from the International Space Station in orbit show a very obviously curved Earth.

And here is where the conspiracy really gets going. To a flat-Earther, any photograph from the International Space Station is just a fake. So too are the famous photographs of the whole round Earth hanging in space that were taken on the Apollo missions. Of course, the Moon landings were faked too. This is a conspiracy theory that swallows other conspiracy theories whole. According to Mark Sargent’s “enclosed world” version of the flat-Earth theory, indeed, space travel had to be faked because there is actually an impermeable solid dome enclosing our flat planet. The US and USSR tried to break through this dome by nuking it in the 1950s: that’s what all those nuclear tests were really about.

Flat-Earthers regard as fake any photographs of the Earth that were taken on the Apollo missions Photograph: Alamy

The intellectual dynamic here, is one of rejection and obfuscation. A lot of ingenuity evidently goes into the elaboration of modern flat-Earth theories to keep them consistent. It is tempting to suppose that some of the leading writers (or, as fans call them, “researchers”) on the topic are cynically having some intellectual fun, but there are also a lot of true believers on the messageboards who find the notion of the “globist” conspiracy somehow comforting and consonant with their idea of how the world works. You might think that the really obvious question here, though, is: what purpose would such an incredibly elaborate and expensive conspiracy serve? What exactly is the point?

It seems to me that the desire to believe such stuff stems from a deranged kind of optimism about the capabilities of human beings. It is a dark view of human nature, to be sure, but it is also rather awe-inspiring to think of secret agencies so single-minded and powerful that they really can fool the world’s population over something so enormous. Even the pro-Brexit activists who warned one another on polling day to mark their crosses with a pen so that MI5 would not be able to erase their votes, were in a way expressing a perverse pride in the domination of Britain’s spookocracy. “I literally ran out of new tin hat topics to research and I STILL wouldn’t look at this one without embarrassment,” confesses Sargent on his website, “but every time I glanced at it there was something unresolved, and once I saw the near perfection of the whole plan, I was hooked.” It is rather beautiful. Bonkers, but beautiful. As the much more noxious example of Scientology also demonstrates, it is all too tempting to take science fiction for truth – because narratives always make more sense than reality.

We know that it’s a good habit to question received wisdom. Sometimes, though, healthy scepticism can run over into paranoid cynicism, and giant conspiracies seem oddly consoling. One reason why myths and urban legends hang around so long seems to be that we like simple explanations – such as that immigrants are to blame for crumbling public services – and are inclined to believe them. The “MMR causes autism” scare perpetrated by Andrew Wakefield, for example, had the apparent virtue of naming a concrete cause (vaccination) for a deeply worrying and little-understood syndrome (autism). Years after it was shown that there was nothing to Wakefield’s claims, there is still a strong and growing “anti-vaxxer” movement, particularly in the US, which poses a serious danger to public health. The benefits of immunisation, it seems, have been forgotten.

The yearning for simple explanations also helps to account for the popularity of outlandish conspiracy theories that paint a reassuring picture of all the world’s evils as being attributable to a cabal of supervillains. Maybe a secret society really is running the show – in which case the world at least has a weird kind of coherence. Hence, perhaps, the disappointed amazement among some of those who had not expected their protest votes for Brexit to count.

And what happens when the world of ideas really does operate as a marketplace? It happens to be the case that many prominent climate sceptics have been secretly funded by oil companies. The idea that there is some scientific controversy over whether burning fossil fuels has contributed in large part to the present global warming (there isn’t) is an idea that has been literally bought and sold, and remains extraordinarily successful. That, of course, is just a particularly dramatic example of the way all western democracies have been captured by industry lobbying and party donations, in which friendly consideration of ideas that increase the profits of business is simply purchased, like any other commodity. If the marketplace of ideas worked as advertised, not only would this kind of corruption be absent, it would be impossible in general for ideas to stay rejected for hundreds or thousands of years before eventually being revived. Yet that too has repeatedly happened.

While the return of flat-Earth theories is silly and rather alarming, meanwhile, it also illustrates some real and deep issues about human knowledge. How, after all, do you or I know that the Earth really is round? Essentially, we take it on trust. We may have experienced some common indications of it ourselves, but we accept the explanations of others. The experts all say the Earth is round; we believe them, and get on with our lives. Rejecting the economic consensus that Brexit would be bad for the UK, Michael Gove said that the British public had had enough of experts (or at least of experts who lurked in acronymically named organisations), but the truth is that we all depend on experts for most of what we think we know.

The second issue is that we cannot actually know for sure that the way the world appears to us is not actually the result of some giant conspiracy or deception. The modern flat-Earth theory comes quite close to an even more all-encompassing species of conspiracy theory. As some philosophers have argued, it is not entirely impossible that God created the whole universe, including fossils, ourselves and all our (false) memories, only five minutes ago. Or it might be the case that all my sensory impressions are being fed to my brain by a clever demon intent on deceiving me (Descartes) or by a virtual-reality program controlled by evil sentient artificial intelligences (The Matrix).

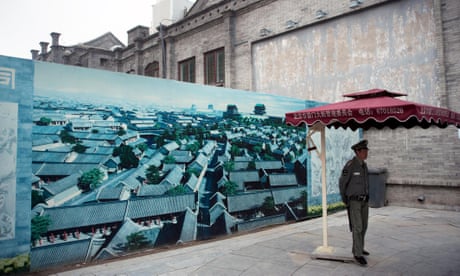

The resurgence of flat-Earth theory has also spawned many web pages that employ mathematics, science, and everyday experience to explain why the world actually is round. This is a boon for public education. And we should not give in to the temptation to conclude that belief in a conspiracy is prima facie evidence of stupidity. Evidently, conspiracies really happen. Members of al-Qaida really did conspire in secret to fly planes into the World Trade Center. And, as Edward Snowden revealed, the American and British intelligence services really did conspire in secret to intercept the electronic communications of millions of ordinary citizens. Perhaps the most colourful official conspiracy that we now know of happened in China. When the half-millennium-old Tiananmen Gate was found to be falling down in the 1960s, it was secretly replaced, bit by bit, with an exact replica, in a successful conspiracy that involved nearly 3,000 people who managed to keep it a secret for years.

Indeed, a healthy openness to conspiracy may be said to underlie much honest intellectual inquiry. This is how the physicist Frank Wilczek puts it: “When I was growing up, I loved the idea that great powers and secret meanings lurk behind the appearance of things.” Newton’s grand idea of an invisible force (gravity) running the universe was definitely a cosmological conspiracy theory in this sense. Yes, many conspiracy theories are zombies – but so is the idea that conspiracies never happen.

The intellectual dynamic here, is one of rejection and obfuscation. A lot of ingenuity evidently goes into the elaboration of modern flat-Earth theories to keep them consistent. It is tempting to suppose that some of the leading writers (or, as fans call them, “researchers”) on the topic are cynically having some intellectual fun, but there are also a lot of true believers on the messageboards who find the notion of the “globist” conspiracy somehow comforting and consonant with their idea of how the world works. You might think that the really obvious question here, though, is: what purpose would such an incredibly elaborate and expensive conspiracy serve? What exactly is the point?

It seems to me that the desire to believe such stuff stems from a deranged kind of optimism about the capabilities of human beings. It is a dark view of human nature, to be sure, but it is also rather awe-inspiring to think of secret agencies so single-minded and powerful that they really can fool the world’s population over something so enormous. Even the pro-Brexit activists who warned one another on polling day to mark their crosses with a pen so that MI5 would not be able to erase their votes, were in a way expressing a perverse pride in the domination of Britain’s spookocracy. “I literally ran out of new tin hat topics to research and I STILL wouldn’t look at this one without embarrassment,” confesses Sargent on his website, “but every time I glanced at it there was something unresolved, and once I saw the near perfection of the whole plan, I was hooked.” It is rather beautiful. Bonkers, but beautiful. As the much more noxious example of Scientology also demonstrates, it is all too tempting to take science fiction for truth – because narratives always make more sense than reality.

We know that it’s a good habit to question received wisdom. Sometimes, though, healthy scepticism can run over into paranoid cynicism, and giant conspiracies seem oddly consoling. One reason why myths and urban legends hang around so long seems to be that we like simple explanations – such as that immigrants are to blame for crumbling public services – and are inclined to believe them. The “MMR causes autism” scare perpetrated by Andrew Wakefield, for example, had the apparent virtue of naming a concrete cause (vaccination) for a deeply worrying and little-understood syndrome (autism). Years after it was shown that there was nothing to Wakefield’s claims, there is still a strong and growing “anti-vaxxer” movement, particularly in the US, which poses a serious danger to public health. The benefits of immunisation, it seems, have been forgotten.

The yearning for simple explanations also helps to account for the popularity of outlandish conspiracy theories that paint a reassuring picture of all the world’s evils as being attributable to a cabal of supervillains. Maybe a secret society really is running the show – in which case the world at least has a weird kind of coherence. Hence, perhaps, the disappointed amazement among some of those who had not expected their protest votes for Brexit to count.

And what happens when the world of ideas really does operate as a marketplace? It happens to be the case that many prominent climate sceptics have been secretly funded by oil companies. The idea that there is some scientific controversy over whether burning fossil fuels has contributed in large part to the present global warming (there isn’t) is an idea that has been literally bought and sold, and remains extraordinarily successful. That, of course, is just a particularly dramatic example of the way all western democracies have been captured by industry lobbying and party donations, in which friendly consideration of ideas that increase the profits of business is simply purchased, like any other commodity. If the marketplace of ideas worked as advertised, not only would this kind of corruption be absent, it would be impossible in general for ideas to stay rejected for hundreds or thousands of years before eventually being revived. Yet that too has repeatedly happened.

While the return of flat-Earth theories is silly and rather alarming, meanwhile, it also illustrates some real and deep issues about human knowledge. How, after all, do you or I know that the Earth really is round? Essentially, we take it on trust. We may have experienced some common indications of it ourselves, but we accept the explanations of others. The experts all say the Earth is round; we believe them, and get on with our lives. Rejecting the economic consensus that Brexit would be bad for the UK, Michael Gove said that the British public had had enough of experts (or at least of experts who lurked in acronymically named organisations), but the truth is that we all depend on experts for most of what we think we know.

The second issue is that we cannot actually know for sure that the way the world appears to us is not actually the result of some giant conspiracy or deception. The modern flat-Earth theory comes quite close to an even more all-encompassing species of conspiracy theory. As some philosophers have argued, it is not entirely impossible that God created the whole universe, including fossils, ourselves and all our (false) memories, only five minutes ago. Or it might be the case that all my sensory impressions are being fed to my brain by a clever demon intent on deceiving me (Descartes) or by a virtual-reality program controlled by evil sentient artificial intelligences (The Matrix).

The resurgence of flat-Earth theory has also spawned many web pages that employ mathematics, science, and everyday experience to explain why the world actually is round. This is a boon for public education. And we should not give in to the temptation to conclude that belief in a conspiracy is prima facie evidence of stupidity. Evidently, conspiracies really happen. Members of al-Qaida really did conspire in secret to fly planes into the World Trade Center. And, as Edward Snowden revealed, the American and British intelligence services really did conspire in secret to intercept the electronic communications of millions of ordinary citizens. Perhaps the most colourful official conspiracy that we now know of happened in China. When the half-millennium-old Tiananmen Gate was found to be falling down in the 1960s, it was secretly replaced, bit by bit, with an exact replica, in a successful conspiracy that involved nearly 3,000 people who managed to keep it a secret for years.

Indeed, a healthy openness to conspiracy may be said to underlie much honest intellectual inquiry. This is how the physicist Frank Wilczek puts it: “When I was growing up, I loved the idea that great powers and secret meanings lurk behind the appearance of things.” Newton’s grand idea of an invisible force (gravity) running the universe was definitely a cosmological conspiracy theory in this sense. Yes, many conspiracy theories are zombies – but so is the idea that conspiracies never happen.

‘When the half-millennium-old Tiananmen Gate was found to be falling down in the 1960s, it was secretly replaced, bit by bit, with an exact replica’ Photograph: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Things are better, one assumes, in the rarefied marketplace of scientific ideas. There, the revered scientific journals have rigorous editorial standards. Zombies and other market failures are thereby prevented. Not so fast. Remember the tongue map. It turns out that the marketplace of scientific ideas is not perfect either.

The scientific community operates according to the system of peer review, in which an article submitted to a journal will be sent out by the editor to several anonymous referees who are expert in the field and will give a considered view on whether the paper is worthy of publication, or will be worthy if revised. (In Britain, the Royal Society began to seek such reports in 1832.) The barriers to entry for the best journals in the sciences and humanities mean that – at least in theory – it is impossible to publish clownish, evidence-free hypotheses.

But there are increasing rumblings in the academic world itself that peer review is fundamentally broken. Even that it actively suppresses good new ideas while letting through a multitude of very bad ones. “False positives and exaggerated results in peer-reviewed scientific studies have reached epidemic proportions in recent years,” reported Scientific American magazine in 2011. Indeed, the writer of that column, a professor of medicine named John Ioannidis, had previously published a famous paper titled Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. The issues, he noted, are particularly severe in healthcare research, in which conflicts of interest arise because studies are funded by large drug companies, but there is also a big problem in psychology.

Take the widely popularised idea of priming. In 1996, a paper was published claiming that experimental subjects who had been verbally primed to think of old age by being made to think about words such as bingo, Florida, grey, and wrinkles subsequently walked more slowly when they left the laboratory than those who had not been primed. It was a dazzling idea, and led to a flurry of other findings that priming could affect how well you did on a quiz, or how polite you were to a stranger. In recent years, however, researchers have become suspicious, and have not been able to generate the same findings as many of the early studies. This is not definitive proof of falsity, but it does show that publication in a peer-reviewed journal is no guarantee of reliability. Psychology, some argue, is currently going through a crisis in replicability, which Daniel Kahneman has called a looming “train wreck” for the field as a whole.

Could priming be a future zombie idea? Well, most people think it unlikely that all such priming effects will be refuted, since there is now such a wide variety of studies on them. The more interesting problem is to work out what scientists call the idea’s “ecological validity” – that is, how well do the effects translate from the artificial simplicity of the lab situation to the ungovernable messiness of real life? This controversy in psychology just shows science working as it should – being self-correcting. One marketplace-of-ideas problem here, though, is that papers with surprising and socially intriguing results will be described throughout the media, and lauded as definitive evidence in popularising books, as soon as they are published, and long before awkward second questions begin to be asked.

Things are better, one assumes, in the rarefied marketplace of scientific ideas. There, the revered scientific journals have rigorous editorial standards. Zombies and other market failures are thereby prevented. Not so fast. Remember the tongue map. It turns out that the marketplace of scientific ideas is not perfect either.

The scientific community operates according to the system of peer review, in which an article submitted to a journal will be sent out by the editor to several anonymous referees who are expert in the field and will give a considered view on whether the paper is worthy of publication, or will be worthy if revised. (In Britain, the Royal Society began to seek such reports in 1832.) The barriers to entry for the best journals in the sciences and humanities mean that – at least in theory – it is impossible to publish clownish, evidence-free hypotheses.

But there are increasing rumblings in the academic world itself that peer review is fundamentally broken. Even that it actively suppresses good new ideas while letting through a multitude of very bad ones. “False positives and exaggerated results in peer-reviewed scientific studies have reached epidemic proportions in recent years,” reported Scientific American magazine in 2011. Indeed, the writer of that column, a professor of medicine named John Ioannidis, had previously published a famous paper titled Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. The issues, he noted, are particularly severe in healthcare research, in which conflicts of interest arise because studies are funded by large drug companies, but there is also a big problem in psychology.

Take the widely popularised idea of priming. In 1996, a paper was published claiming that experimental subjects who had been verbally primed to think of old age by being made to think about words such as bingo, Florida, grey, and wrinkles subsequently walked more slowly when they left the laboratory than those who had not been primed. It was a dazzling idea, and led to a flurry of other findings that priming could affect how well you did on a quiz, or how polite you were to a stranger. In recent years, however, researchers have become suspicious, and have not been able to generate the same findings as many of the early studies. This is not definitive proof of falsity, but it does show that publication in a peer-reviewed journal is no guarantee of reliability. Psychology, some argue, is currently going through a crisis in replicability, which Daniel Kahneman has called a looming “train wreck” for the field as a whole.

Could priming be a future zombie idea? Well, most people think it unlikely that all such priming effects will be refuted, since there is now such a wide variety of studies on them. The more interesting problem is to work out what scientists call the idea’s “ecological validity” – that is, how well do the effects translate from the artificial simplicity of the lab situation to the ungovernable messiness of real life? This controversy in psychology just shows science working as it should – being self-correcting. One marketplace-of-ideas problem here, though, is that papers with surprising and socially intriguing results will be described throughout the media, and lauded as definitive evidence in popularising books, as soon as they are published, and long before awkward second questions begin to be asked.

China’s memory manipulators

It would be sensible, for a start, for us to make the apparently trivial rhetorical adjustment from the popular phrase “studies show …” and limit ourselves to phrases such as “studies suggest” or “studies indicate”. After all, “showing” strongly implies proving, which is all too rare an activity outside mathematics. Studies can always be reconsidered. That is part of their power.

Nearly every academic inquirer I talked to while researching this subject says that the interface of research with publishing is seriously flawed. Partly because the incentives are all wrong – a “publish or perish” culture rewards academics for quantity of published research over quality. And partly because of the issue of “publication bias”: the studies that get published are the ones that have yielded hoped-for results. Studies that fail to show what they hoped for end up languishing in desk drawers.

One reform suggested by many people to counteract publication bias would be to encourage the publication of more “negative findings” – papers where a hypothesis was not backed up by the experiment performed. One problem, of course, is that such findings are not very exciting. Negative results do not make headlines. (And they sound all the duller for being called “negative findings”, rather than being framed as positive discoveries that some ideas won’t fly.)

The publication-bias issue is even more pressing in the field of medicine, where it is estimated that the results of around half of all trials conducted are never published at all, because their results are negative. “When half the evidence is withheld,” writes the medical researcher Ben Goldacre, “doctors and patients cannot make informed decisions about which treatment is best.”Accordingly, Goldacre has kickstarted a campaigning group named AllTrials to demand that all results be published.

When lives are not directly at stake, however, it might be difficult to publish more negative findings in other areas of science. One idea, floated by the Economist, is that “Journals should allocate space for ‘uninteresting’ work, and grant-givers should set aside money to pay for it.” It sounds splendid, to have a section in journals for tedious results, or maybe an entire journal dedicated to boring and perfectly unsurprising research. But good luck getting anyone to fund it.

The good news, though, is that some of the flaws in the marketplace of scientific ideas might be hidden strengths. It’s true that some people think peer review, at its glacial pace and with its bias towards the existing consensus, works to actively repress new ideas that are challenging to received opinion. Notoriously, for example, the paper that first announced the invention of graphene – a way of arranging carbon in a sheet only a single atom thick – was rejected by Nature in 2004 on the grounds that it was simply “impossible”. But that idea was too impressive to be suppressed; in fact, the authors of the graphene paper had it published in Science magazine only six months later. Most people have faith that very well-grounded results will find their way through the system. Yet it is right that doing so should be difficult. If this marketplace were more liquid and efficient, we would be overwhelmed with speculative nonsense. Even peremptory or aggressive dismissals of new findings have a crucial place in the intellectual ecology. Science would not be so robust a means of investigating the world if it eagerly embraced every shiny new idea that comes along. It has to put on a stern face and say: “Impress me.” Great ideas may well face a lot of necessary resistance, and take a long time to gain traction. And we wouldn’t wish things to be otherwise.

In many ways, then, the marketplace of ideas does not work as advertised: it is not efficient, there are frequent crashes and failures, and dangerous products often win out, to widespread surprise and dismay. It is important to rethink the notion that the best ideas reliably rise to the top: that itself is a zombie idea, which helps entrench powerful interests. Yet even zombie ideas can still be useful when they motivate energetic refutations that advance public education. Yes, we may regret that people often turn to the past to renew an old theory such as flat-Earthism, which really should have stayed dead. But some conspiracies are real, and science is always engaged in trying to uncover the hidden powers behind what we see. The resurrection of zombie ideas, as well as the stubborn rejection of promising new ones, can both be important mechanisms for the advancement of human understanding.

Thursday, 21 April 2016

'If you don't have the right culture, it's hard to be a high-performance team'

Former South Africa rugby captain Francois Pienaar talks about his role on Cricket South Africa's review panel. INTERVIEW BY FIRDOSE MOONDA in Cricinfo

"I have been really privileged to get involved in high-performance teams that have won" © Getty Images

Despite consistently boasting some of the best players in the world, South Africa remain the only top-eight team that has never reached a World Cup final or World T20 final. After a year in which both the men's and women's teams crashed out of a major tournament in the first round, while the Under-19 team failed to defend their title, Cricket South Africa are determined to discover why and have appointed a four-person panel to investigate.

The highest-profile person on that panel is Francois Pienaar, the Springbok (rugby) World Cup-winning captain in 1995. He and coach Kitch Christie hold an enviable 100% winning record, while Pienaar also enjoyed great success at domestic level. It is hoped some of his knowledge will rub off on the cricketers.

Pienaar spoke at the launch of the Cape Town Marathon, for which he is an ambassador, about his involvement with Cricket South Africa's review panel, what it means to be a high-performance team, and how to create a winning culture.

Why did you agree to be involved in the CSA review?

Passion. I love this country and I have been involved in cricket - I've played cricket at school, I played Nuffield Cricket, I was involved in the IPL marketing when it came here in 2009. As a panel, we all know things about high-performance and closing out games. I have been involved in a number of initiatives where we've put structures in place and they have borne fruit. This is just a privilege, to be honest.

How will you and your fellow panelists approach the review?

What we will try and learn is what the trends over the last ten years are. We will look at trends, selection, stats and come up with recommendations.

What do you, specifically, hope to bring to the review?

A different thinking from not being in the sport, coming from outside the sport. I have been really privileged to get involved in high-performance teams that have won.

Can you talk about some of the teams you were involved with and how they achieved what you call high-performance status? In 1993, the Lions won 100% of their games.

In 1994, we won 90%. As captain and coach of the Springbok rugby team, Kitch Christie and myself, we never lost. There was a certain culture of that side and a way of doing things. Our management team fulfilled high-performing roles in getting us to get a shot at the title. Even then, there are no guarantees. When you get to the final, it's a 50-50 call and it's the smart guys who work out the margins. It's all about the margins.

Then I went over to England and rugby was really amateur. I was a player-coach at Saracens, I needed to put those processes in place and, luckily, took the team to win their first ever cup. Those sort of things I am really proud of.

A brand to admire: the All Blacks have won the last two World Cups © Getty Images

Have you seen anything similar to that in cricket?

Then I went over to England and rugby was really amateur. I was a player-coach at Saracens, I needed to put those processes in place and, luckily, took the team to win their first ever cup. Those sort of things I am really proud of.

A brand to admire: the All Blacks have won the last two World Cups © Getty Images

Have you seen anything similar to that in cricket?

I had a magnificent session with the Aussies before the Ashes in the early 2000s. They asked me to do a session on margins and big games and how to close out games. I was sort of embarrassed. The best cricket team in the world by a long shot was asking me, but I found it so interesting. My payment there was that I got an insight into how they run their team. Steve Waugh as a captain and a leader - wow! I got so much from that.

What makes a high-performance team?

What makes a high-performance team?

Culture trumps strategy for breakfast. If you don't have the right culture in any organisation, it's very hard to be a high-performance team. The brand must be stronger than anything else. CEOs and coaches and captains come and go but you have to understand the culture and the core of why teams are high-performance teams, and you can't tinker with that. As soon as you start tinkering with that, then you stand the risk of not remaining a high-performance team.

Look at the All Blacks brand [New Zealand rugby], and how they nurture and love and embrace that brand. One of the nicest things for me was at the last World Cup when Graham Henry, who coached them when they won the World Cup in 2011, was coaching Argentina and New Zealand were playing against Argentina in the opening match at Wembley. I was there. My question would be what would happen in South Africa if a team of ours - cricket, rugby, soccer - if the coach who had won the World Cup in the previous outing is now coaching the opposition in the opening match. Would we invite him to lunch with the team the day before the game? I think not. They did that. The All Blacks invited Henry because he loves the guys, he is part of that brand, part of that passion, so why should they not invite him? They knew, if we are not smarter than him, if we don't train hard, then we don't deserve to win. It's about the culture.

Then afterwards, Sonny Bill Williams gave away his medal. Was it him or part of the culture? I would think it's part of the culture. Same with Richie McCaw. Why did he not retire in the World Cup? Because if he did, it would have been about him and not about the team, and he knew it needed to be about the team. That's my take.

How do you create a winning culture?

Look at the All Blacks brand [New Zealand rugby], and how they nurture and love and embrace that brand. One of the nicest things for me was at the last World Cup when Graham Henry, who coached them when they won the World Cup in 2011, was coaching Argentina and New Zealand were playing against Argentina in the opening match at Wembley. I was there. My question would be what would happen in South Africa if a team of ours - cricket, rugby, soccer - if the coach who had won the World Cup in the previous outing is now coaching the opposition in the opening match. Would we invite him to lunch with the team the day before the game? I think not. They did that. The All Blacks invited Henry because he loves the guys, he is part of that brand, part of that passion, so why should they not invite him? They knew, if we are not smarter than him, if we don't train hard, then we don't deserve to win. It's about the culture.

Then afterwards, Sonny Bill Williams gave away his medal. Was it him or part of the culture? I would think it's part of the culture. Same with Richie McCaw. Why did he not retire in the World Cup? Because if he did, it would have been about him and not about the team, and he knew it needed to be about the team. That's my take.

How do you create a winning culture?

Let's go back to rugby. Every World Cup that has been won since 1987, the core of that winning national team came from the club side that dominated. So that side knew how to win. Like in 1995, the core of our team was from the Lions. If you infuse that culture with incredible players, they will enhance the way you do things.

"We will look at trends, selection, stats and come up with recommendations" © IDI/Getty Images

Are there other elements that go into creating a winning team?

Form is very important and so are combinations - they have to work very well - and then there is leadership. How do the leaders close a game down, how do they make decisions, and how do you work with other leaders in the team to do that?

Rugby is a fairly simple game: it's about how easy you release pressure, your exit strategy, and how you stay unpredictable on attack. For that to happen, there are certain elements that need to fall into place. But the overarching thing is, do you have the right culture, have the right guys in form, have the right combinations and the leaders? Can they execute? And by leaders it's not only the captain, it's the coaches, the management staff. If you can do that right, you will be competitive a lot of the time, and if you can bottle that so that when the next guy comes, you pass the baton - you can't change that. Bottle it, understand it, love it. You'll be on the right track.

Is one of South Africa's problems that they have not found a way of gaining or transferring that knowledge?

The transfer of knowledge is something I am quite interested in discussing. Do we do that, and what are the reasons for us not doing it? In rugby, we've never had that culture. We don't have ex-coaches, for example, involved. We have got universities, schools - how can we bottle that, how can we work together? The transfer of knowledge and the sharing of ideas, we need to rekindle that.

Will transformation form part of the review?

Everything is open for discussion and it should be. If you want to do a proper job, you should have the opportunity to ask questions about all elements that enhance high-performance.

Tuesday, 31 March 2015

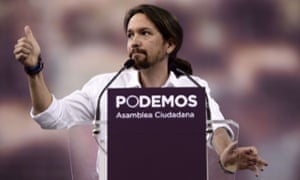

The Podemos revolution: how a small group of radical academics changed European politics

At the start of the 2008 academic year, Pablo Iglesias, a 29-year-old lecturer with a pierced eyebrow and a ponytail greeted his students at the political sciences faculty of the Complutense University in Madrid by inviting them to stand on their chairs. The idea was to re-enact a scene from the film Dead Poets Society. Iglesias’s message was simple. His students were there to study power, and the powerful can be challenged. This stunt was typical of him. Politics, Iglesias thought, was not just something to be studied. It was something you either did, or let others do to you. As a professor, he was smart, hyperactive and – as a founder of a university organisation called Counter-Power – quick to back student protest. He did not fit the classic profile of a doctrinaire intellectual from Spain’s communist-led left. But he was clear about what was to blame for the world’s ills: the unfettered, globalised capitalism that, in the wake of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, had installed itself as the developed world’s dominant ideology.

Iglesias and the students, ex-students and faculty academics worked hard to spread their ideas. They produced political television shows and collaborated with their Latin American heroes – left-leaning populist leaders such as Rafael Correa of Ecuador or Evo Morales of Bolivia. But when they launched their own political party on 17 January 2014 and gave it the name Podemos (“We Can”), many dismissed it. With no money, no structure and few concrete policies, it looked like just one of several angry, anti-austerity parties destined to fade away within months.

A year later, on 31 January 2015, Iglesias strode across a stage in Madrid’s emblematic central square, the Puerta del Sol. It was filled with 150,000 people, squeezed in so tightly that it was impossible to move. He addressed the crowd with the impassioned rhetoric for which opponents have branded him a dangerous leftwing populist. He railed against the monsters of “financial totalitarianism” who had humiliated them all. He told Podemos’s followers to dream and, like that noble madman Don Quixote, “take their dreams seriously”.Spain was in the grip of historic, convulsive change. The serried crowd were heirs to the common folk who – armed with knives, flowerpots and stones – had rebelled against Napoleonic troops in nearby streets two centuries earlier. “We can dream, we can win!” he shouted.

Polls suggest that he is right. Since 1982, Spain has been governed by only two parties. Yet El País newspaper now places Podemos at 22%, ahead of both the ruling conservative Partido Popular (PP) and its leftwing opposition Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE). If Podemos can grow further, Iglesias could become prime minister after elections that are expected in November. This would be an almost unheard-of achievement for such a young party.

Many in the Puerta del Sol longed to see that day. “Yes we can! Yes we can!” they chanted. Other onlookers shivered, recalling Iglesias’s praise for Venezuela’s late president Hugo Chávez and fearing an eruption of Latin American-style populism in a country gripped by debt, austerity and unemployment. But without Podemos, supporters feared, Spain faced the prospect of becoming like Greece, with its disintegrating welfare state, crumbling middle class and rampant inequality.

On stage that day, Iglesias declared that Podemos would take back power from self-serving elites and hand it over to the people. To do that, the new party needs votes. If that means arousing emotions and being accused of populism, so be it. And, as the party’s founders have already shown, if they have to renounce some of their ideas in order to broaden their appeal, or risk upsetting some in their grassroots movement by tightening central control, they are ready to do that, too. The aim, after all, is to win.

At first glance, Podemos’s dizzying rise looks miraculous. In truth, the project evolved over a long time, though even the organisers did not know it would eventually spawn a party, or that a global financial crisis would provide their opportunity. In Spain today, one-third of the labour force is either jobless or earns less than the minimum annual salary of €9,080. In big cities, the sight of people raiding bins for food or things to sell – a rarity in pre-crisis Spain – is no longer shocking. A fatalistic gloom has settled over a country that rode a wave of optimism for three decades after it transformed itself from dictatorship to democracy. After years of economic growth, the financial crisis burst Spain’s construction bubble. Countless corruption cases – involving both the PP and PSOE – have stoked widespread anger towards the established political class. “A political crisis is a moment for daring,” Iglesias told an audience recently. “It is when a revolutionary is capable of looking people in the eye and telling them, ‘Look, those people are your enemies.’”

He is not the first Pablo Iglesias to shake Spain’s political order. He is named after the man who founded the PSOE in 1879. (His parents first met at a remembrance ceremony in front of Iglesias’s tomb.) As a teenager, Iglesias was a member of the Communist Youth in Vallecas, one of Madrid’s poorest and proudest barrios. He still lives there today, in a modest apartment on a graffiti-daubed 1980s estate of medium- and high-rise blocks. (“Defend your happiness, organise your rage,” reads one graffiti slogan.) Even as a teenager, he was “a leader and great seducer”, recalled a senior Podemos member who had attended the same youth group. Iglesias studied law at the Complutense University before taking a second undergraduate degree in political science. He went on to write a PhD thesis on disobedience and anti-globalisation protests that was awarded a prestigious cum laude grade

.

Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias rails against the monsters of ‘financial totalitarianism’, and tells the party’s followers to ‘take their dreams seriously’. Photograph: Dani Pozo/AFP/Getty