'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Tuesday, 16 January 2024

Friday, 29 September 2023

Saturday, 27 May 2023

Wednesday, 26 October 2022

Controversial new research suggests SARS-CoV-2 bears signs of genetic engineering

The claim has yet to be peer-reviewed writes The Economist

Astring of about 30,000 genetic letters were all that it took to start the nightmare of covid-19, the death toll from which is likely to be more than 20m. Exactly how this story began has been hotly contested. Many think that covid-19’s emergence was a zoonosis—a spillover, as so many new pathogens are, from wild animals, for it resembles a group of coronaviruses found in bats. Others have pointed to the enthusiastic coronavirus engineering going on in laboratories around the world, but particularly in Wuhan—the Chinese city where the virus was first identified. In February 2021 a team of scientists assembled by the World Health Organisation (who) to visit Wuhan said a laboratory leak was extremely unlikely. However, this conclusion was subsequently challenged by the who’s boss, who said ruling out this theory was premature.

Two recent publications appear to have bolstered the case for a natural origin connected to a “wet market” in Wuhan. These markets sell live animals, often housed in poor conditions, and are known to be sites where new pathogens jump from animal to human. Early cases of covid-19 clustered around this market. But critics counter that there are so many missing data about the epidemic’s initial days that this portrait may be inaccurate.

The opposing idea of a leak from a laboratory is not implausible. The accidental escape of viruses from labs is more common than many people realise. The flu epidemic of 1977 is thought to have started this way. But an escaped virus does not imply an engineered virus. Virology labs are also full of the unengineered sort.

Research such as that done in Wuhan offers a number of ways for a virus to leak out. A researcher on a field trip could have picked it up in the wild and then returned to Wuhan, and so spread it to others there. Or someone might have been infected with a wild-collected virus in the laboratory itself. But some argue that sars-cov-2 could have been assembled in a laboratory from other viruses that were already to hand, and then leaked out.

Into this fray comes an analysis from an unlikely source. Alex Washburne is a mathematical biologist who runs Selva, a small startup in microbiome science based in New York. He is an outsider, although he has worked in the past on virological modelling as a researcher at Montana State University. For this study, Dr Washburne collaborated with two other scientists. One is Antonius VanDongen, an associate professor of pharmacology at Duke University, in North Carolina. The other, Valentin Bruttel, is a molecular immunologist at the University of Würzburg, Germany. Dr Washburne and Dr VanDongen have been active proponents of an investigation into the lab-leak theory.

The trio base their claim on a novel method of detecting plausibly lab-engineered viruses. Their analysis, published on October 20th on bioRxiv, a preprint server, suggests sars-cov-2 has some genomic features that they say would appear if the virus had been stitched together by some form of genetic engineering. By examining how many of these putative stitching sites sars-cov-2 has, and how relatively short these pieces are, they attempt to assess how much the virus resembles others found in nature.

They start from the presumption that creating a genome as long as that of sars-cov-2 would mean combining shorter fragments of existing viruses together. For a coronavirus genome assembly they say an ideal arrangement would be to use between five and eight fragments, all under 8,000 letters long. Such fragments are created using restriction enzymes. These are molecular scissors which cut genomic material at particular sequences of genetic letters. If a genome does not have such restriction sites in opportune places, researchers typically create new ones of their own.

They argue that the distribution of restriction sites for two popular restriction enzymes—BsaI and BsmBI—are “anomalous” in the sars-cov-2 genome. And the length of the longest fragment is far shorter than would be expected. They determined this by taking 70 disparate coronavirus genomes (not including sars-cov-2) and cutting them into pieces with 214 commonly used restriction enzymes. From the resulting collection, they were able to work out the expected lengths of fragments when coronaviruses are cut into varying numbers of pieces.

The paper, which as a preprint has received no formal peer review, and which has not been accepted for publication in a journal, will be picked apart in the coming days—as well it should be, for this is the way that science works. Early reactions, though, have been deeply divided. Francois Balloux, a professor of computational systems biology at University College London, said he found the results intriguing. “Contrary to many of my colleagues, I couldn’t identify any fatal flaw in the reasoning and methodology. The distribution of BsaI/BsmBI restriction sites in sars-cov-2 is atypical”. Dr Balloux said these needed to be assessed in good faith. But Edward Holmes, an evolutionary biologist and virologist at the University of Sydney, said that every one of the features identified by the paper was natural and already found in other bat viruses. If someone were engineering a virus they would undoubtedly introduce some new ones. He added, “there are a whole range of technical reasons why this is complete nonsense.”

Sylvestre Marillonnet, an expert in synthetic biology at the Leibniz Institute for Plant Biochemistry, in Germany, agreed that the number and distribution of these restriction sites did not look quite random, and that the number of silent mutations found in these sites did suggest that sars-cov-2 might have been engineered. (Silent mutations are a result of engineers wanting to make changes in a sequence of genetic material without making changes to the proteins encoded by that sequence.) But Dr Marillonnet also said that there are arguments against this hypothesis. One of them is the tiny length of one of the six fragments, something that “does not seem logical to me”.

The other point Dr Marillonnet makes is that it is not necessary for the restriction sites to have been present in the final sequence. “Why would people introduce and leave sites in the genome when it is not needed?” he wondered. Previous arguments in support of the possibility of a lab leak have stressed that a manipulated virus would not need to have any such tell-tales. However, Justin Kinney, a professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, in New York, said that researchers have created coronaviruses before and left such sites in the genome. He said the genetic signature indicates a virus ready for further experiments and said it needed to be taken seriously, but warned the paper needed rigorous peer review.

Erik van Nimwegen, from the University of Basel, says there are only small scraps of information and it is “hard to pull anything definitive out of that”. He adds, “one cannot really exclude at all that such a constellation of sites may have occurred by chance”. The authors of the paper concede this is the case. Kristian Andersen, a professor of immunology and microbiology, at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, described the pattern, on Twitter, as “random noise”.

Any conclusion that sars-cov-2 was engineered will be hotly contested. China denies the virus came from a Chinese lab, and has asked for investigations into whether it may have originated in America. Dr Washburne and his colleagues say their predictions are testable. If a progenitor genome to sars-cov-2 is found in the wild with restriction sites that are the same, or intermediate, it would raise the chances that this pattern evolved by chance.

Any widely supported conclusion that the virus was genetically engineered would have profound ramifications, both political and scientific. It would put in a new light the behaviour of the Chinese government in the early days of the outbreak, particularly its reluctance to share epidemiological data from those days. It would also raise questions about what was known, when, and by whom about the presumably accidental escape of an engineered virus. For now, this is a first draft of science, and needs to be treated as such. But the scrutineers are already at work.

Tuesday, 2 August 2022

Thursday, 14 April 2022

Monday, 4 April 2022

Tuesday, 8 March 2022

Despite all the punditry, the BJP's "likely" to win UP

I thought of Philip da as I watched the exit polls for the 2022 Uttar Pradesh assembly election. The forecast of another term for the Bharatiya Janata Party was distressing, but it did not surprise me. The margin of the BJP’s victory projected by some – 300 plus seats and double digit lead in vote share – was and still is shocking. But I was not surprised by the broad direction and the operational conclusion of most of the exit polls. An article by Philip Oldenburg three decades ago had prepared me for such shocks.

This is not how my friends see it. Most of my friends, fellow travellers and comrades have been expecting nothing short of a rout for the BJP. For the last two months they have shared stories about how the BJP was wiped out in Western UP, seat-by-seat analysis of the decimation of the BJP in Poorvanchal and videos of how Akhilesh Yadav is drawing big crowds all over the state. I understand their sense of shock over the exit polls now. If a mediocre government with a cardboard of a leader manages to win popular approval, and that too within a year of one of the worst public health disasters followed by a powerful anti-government farmers’ movement, it should surprise anyone.

I was cured of this surprise over the last six weeks, as I travelled through Uttar Pradesh. I had heard about popular discontent against the Yogi Adityanath government. I had expected anger against its poor record on development, welfare and law-and-order. I thought people would never forget the hardship faced by migrant workers during the lockdown or at least the callousness they suffered during the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. We had documented how the BJP reneged on its entire manifesto promises to the farmers of UP. I had seen the power of the farmers’ movement in the Western UP.

Yet, on the ground, I did not find an anti-incumbency mood in the state. Not because everyone was happy. I encountered a vast range of deep disappointments, complaints against the officials and political leaders and intense anxieties about their life and livelihood. But this did not translate into popular anger against the BJP government. There was a “commonsense” shared by ordinary voters, everyone except Yadavs, Jatavs and Muslims.

Capturing the ‘commonsense’

This commonsense would come out in a typical conversation in rural UP. You ask the people about their conditions, and you hear a litany of complaints (which the unsuspecting journalist mistakes for intense anti-incumbency): ‘Things are really bad. Our family income has fallen over the last two years. There is no work for the educated youth. So many of us lost the jobs we had. Children could not study during the pandemic. Many old people in our village died without any medical support. We could not sell our crops for the official (MSP) price.’ Any mention of stray cattle invites a tirade: Naak me dam kar diya hai (bane of our existence). And mehngai (price rise)? Don’t even start talking about it.

Now you expect them to blame it all on the rulers. But a question about the performance of the Adityanath government gets a surprisingly positive response: “Achhi sarkar hai, theek kaam kiya hai (It’s a decent government, has done good work).” Before you can ask, they recount two benefits. Everyone got additional foodgrain, over and above the standard quota, plus cooking oil and chana. And almost everyone, including many Samajwadi Party (SP) voters, mentions improved law and order. “Hamari behen betiyan surakshit hain (our women are safe)” is a standard refrain.

But what about all the problems they just recounted? You ask this question and they get into rationalising on the BJP’s behalf. ‘What can the government do about these things? Coronavirus was global, so was inflation. Things would have been worse but for Modiji. Is he responsible for not feeding cows once they get old?’ While every small achievement of the BJP, real or imagined, was known to every voter, the SP could not make some of the biggest pain points into election issues. I hardly met any voter who would know some of the main poll planks of Akhilesh Yadav’s party.

It would be a mistake to place this commonsense in the standard register of pro- or anti-incumbency. This is not about a routine assessment of the work done by a government. The voters seem to have made up their mind before they start reasoning. They are not judges, but advocates. They know which side of the argument they stand, who stands with them. The BJP has set up an emotional bond with a vast segment of the voters. They are willing to suspend disbelief, condone misgovernance, undergo material suffering and still stay with their ‘own’ side. They do not mention Ayodhya or Kashi temple on their own, but the Hindu-Muslim divide is very much a subtext of this shared commonsense.

What about caste? Needless to say, this commonsense does not fully cut across all castes and communities. Yet the caste arithmetic does not work to the SP’s advantage. No doubt, the Yadavs were fully mobilised behind the SP, “110 per cent” as they say in Hindi. The Muslims had virtually no choice except the SP, notwithstanding the attractive rhetoric of Asaduddin Owaisi. The SP played smart by giving fewer tickets to Yadavs and Muslims. The Muslim voters in turn played wise by keeping a low profile, though Yadav support for SP was visible and aggressive. The Yadavs and Muslims refused to share the pro-incumbent commonsense. They would pick holes in every pro-government rationalisation. Their polarisation no doubt helped the SP, but that was never going to be enough.

Illusory SP wave?

I discovered that my friends had seriously over-estimated support for the SP among non-Yadav, non-Muslim voters. The famed disaffection of the Brahmins from the Thakur rule of CM Adityanath did not translate into anything on the ground. The so-called ‘upper’ castes continue to be the strongest caste vote bank for the BJP. There was some erosion among the farming communities like Jats, Kurmis and Mauryas, but much less than my friends imagined. With a few exceptions – Nishads at certain places, for example — the lower Other Backward Classes (OBCs) stayed solidly with the BJP. Every SP supporter counted on the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP)’s disaffected voters going to the SP. I found little evidence of that, except among a few Pasis. If anything, the former BSP voters and the ex-Congress supporters turned more towards the BJP than the SP.

So, was this impression of a wave in favour of Akhilesh Yadav and his party completely illusory? Not quite. There was, undoubtedly, a surge for the SP everywhere. The massive crowds for Akhilesh’s public meetings were for real. Exit polls suggest that the SP will better its best ever performance of 29 per cent in terms of votes. It needed to improve its 2017 performance by around 15 percentage points and bring the BJP down by at least 5 points to win this election. That was always a Herculean ask. While everyone noted, rightly, that the SP was gaining, not many asked the real question: how much and wide were its gains?

In a bipolar election, the threshold of victory goes up. The SP’s best was not going to be good enough. Also, the SP’s gains were not automatically the BJP’s losses. Exit polls confirm that a shift from multi-cornered contests to a two-horse race meant that while the SP has gained, the BJP has managed to retain or better its vote share. While those who shifted away from the BJP were visible and voluble, those who stayed with or shifted towards the BJP remained silent. The India Today-Axis My India exit poll reports a massive advantage to the BJP among women voters. Most observers, including this writer, missed this major factor.

Talk to voters

While I continue to believe and hope that the race is closer than predicted by the exit polls, I have one piece of advice for my friends. If the BJP wins this election, please don’t jump to conclusions about poll rigging. Not that the BJP is above such manipulation or that the Election Commission is in any position to withstand it. But in this instance, it is not about EVM rigging; it is about rigging the screen of our TV and smartphones. It is not booth capturing, but mindscape capturing, an effective capture of the moral and political commonsense.

This brings me to Philip Oldenburg, or Philip da as I call him, one of the most insightful though less celebrated scholars of Indian politics. In 1988 he wrote an article why most ‘political pundits’ and political activists failed to anticipate the Congress wave in the 1984 Lok Sabha election. His argument is very simple: a triad of political leaders, journalists and local informants keep speaking to one another about election trends and manufacture a consensus about the likely electoral outcome. The problem is that none of them deigns to speak to ordinary voters. This is what pollsters do and that is why they tend to get it right.

As I travelled through Uttar Pradesh across the last few weeks, this lesson came back to me again and again. I wish my friends would stop speaking to one another, stop listening to media noise and simply go out to speak to ordinary citizens. Our political challenge is to connect to and intervene into the shared moral and political commonsense of the voters. It is not too late to learn this lesson. We are still two years from 2024.

Thursday, 9 December 2021

Who will apologise for plasma therapy? It was a disaster for Covid-19, govt hospitals knew

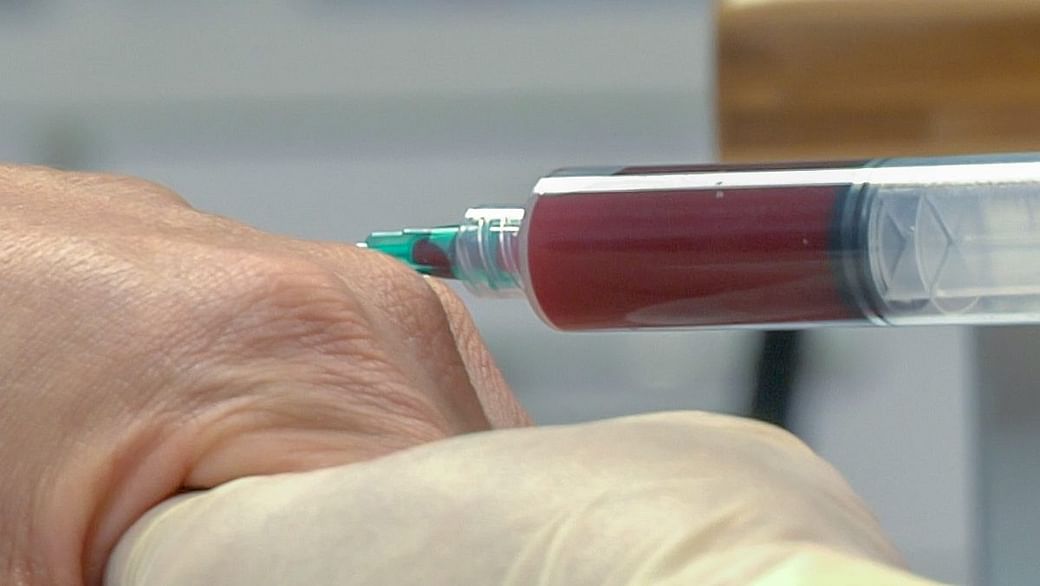

Plasma therapy was administered to Covid-19 patients during the second wave in India | Wikipedia

Plasma therapy was administered to Covid-19 patients during the second wave in India | WikipediaThe closing pages of the 18th-century masterpiece fiction The Story of the Stone revealed the essence of the Tao’s message. In Lao Tzu’s words, it means that “Things are not as they seem, that the Eloquent may Stammer, that Perfection may seem Flawed, that Truth is Fiction, Fiction Truth.”

The truth is neither black nor white, it’s grey—the handling of the second wave of Covid-19 is a testimony to that fact.

Disaster that escaped public eye

In the midst of the second wave of Covid-19 with panic all around, a lot of therapeutic disasters were played out, and without a doubt, they were inspired by a lack of knowledge. Instead, they were fueled with a desire for one-upmanship and copycat fame. Some of the doctors unwittingly orchestrated this therapeutic mess. On one side, we had the armchair experts who were not running Covid-19 centres and had shut down their institutes. On the other, doctors in central government hospitals like the Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in Delhi were running Out Patient Departments (OPDs) and wards. They were possibly following half-baked regimens with little proof, as there were lives at stake.

While some medications were possibly harmless and cheap like Ivermectin or HCQS, the others were ridiculously expensive, and no one was wiser about their efficacy. One of them was plasma therapy. Of course, the Indian medical system and healthcare did not have the time for a randomised trial to test a placebo. But the origin of the mess was thus created right here in the capital of the country.

One may ask—who would be the expert to decide on its efficacy? The clear answer is a clinician in a hospital, handling patients with an active plasma extraction centre. But what transpired is that a centre dedicated to liver care with nil experience in Covid-19 treatment proposed the idea that plasma might help. Then came the now-famous statement of Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, saying that Delhi opened the first plasma bank in the world. That set off a chain reaction, and within a few weeks, hospitals followed suit.

It wasn’t the solution

Plasma is a component of the blood that is believed to have antibodies to diseases. Here, it was believed that Covid-19 patients would benefit from such therapy. This was when even the use of Intravenous immunoglobulin (IV IgG), a related plasma-based therapy that had been available for years, wasn’t effective in most disorders. This was also when we all knew that the so-called antibody tests of Covid-19 patients are negative or low positive. In fact, what is even more comical is that the quantity of antibodies in plasma is probably too little to do anything. And the ultimate irony is that therapy works in isolation, but here we had a plethora of medicines being administered, and it was not possible to pinpoint what was working behind the treatment.

Plasma does not come cheap, as it has to be extracted from patients. Thanks to the CM calling for plasma donation with great zeal and fanfare, the concept spread like wildfire. Intermediaries and ‘scamsters’ came in, and patients paid lakhs to get treatment, that too with dubious efficacy. Most doctors were inundated with calls for plasma, and we didn’t know what and where to arrange it for so many patients.

I know of patients who sold their belongings and went broke, partly because of plasma therapy and of course, Remdesivir, which has now been yanked off from all the guidelines. One of the members of our department, who had recovered from Covid-19, needed to give plasma to her own grandfather. He was admitted to the hospital, administered plasma but to no avail.

Trading fact for fame

Therefore, it is a must to understand the value of a placebo trial. Here, an identical-looking therapy is given to assess whether the active therapy—plasma, in this case—does anything substantial. A 30 per cent response rate is considered to be mostly placebo, or inactive, and that is the value of a placebo-controlled study.

There are numerous variables that determine the success of therapy in Covid-19, and assigning the credit to plasma showed a remarkable lack of foresight. At this juncture, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), in a multicentric study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ), found that plasma wasn’t so good. But the public opinion swayed by the hospitals who pioneered the concept pilloried the paper and trashed it. Such was the distrust in our own country’s research that none wanted to get off the plasma bandwagon. Countless patients spent their life savings on what was a highly questionable therapy. And the charade continued till the second wave subsided.

The breakthrough

As always, we waited for a foreign journal to agree to a local finding, which was not surprising to a lot of us in the government hospitals. The landmark paper in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) showed that there was “No significant differences in clinical status or overall mortality between patients treated with convalescent plasma and those who received placebo.” It has been cited 455 times since it was published in February 2021. The number exceeds the citations of any of the papers published by the ‘experts’ who rolled out an untried therapy on the nation.

To add insult to injury, a section of the print media, which studiously avoided criticising them because their publications were the benefactors of full pages advertisements on plasma banks. To make it worse, some of the names suggested for the Padma awards this year included the plasma therapy pioneers.

Who takes the responsibility?

In retrospect, what needs to be asked is—who will pay for the loss of life savings and the death of patients who were given plasma therapy? Who will fill in the gaps for the distrust in medical care? Will the experts apologise? Who will apologise for pillorying the ICMR’s report that could have nipped this in the bud? But no one really apologises for such things in India.

As Donald Keough said, “The truth is, we are not that dumb and we are not that smart.” The plasma blitzkrieg was neither dumb nor smart; it was callous, and someone should be paying for the negligence today or tomorrow.

Friday, 29 October 2021

Wednesday, 6 October 2021

Tuesday, 14 September 2021

Thursday, 2 September 2021

Has Covid ended the neoliberal era?

by Adam Tooze in The Guardian

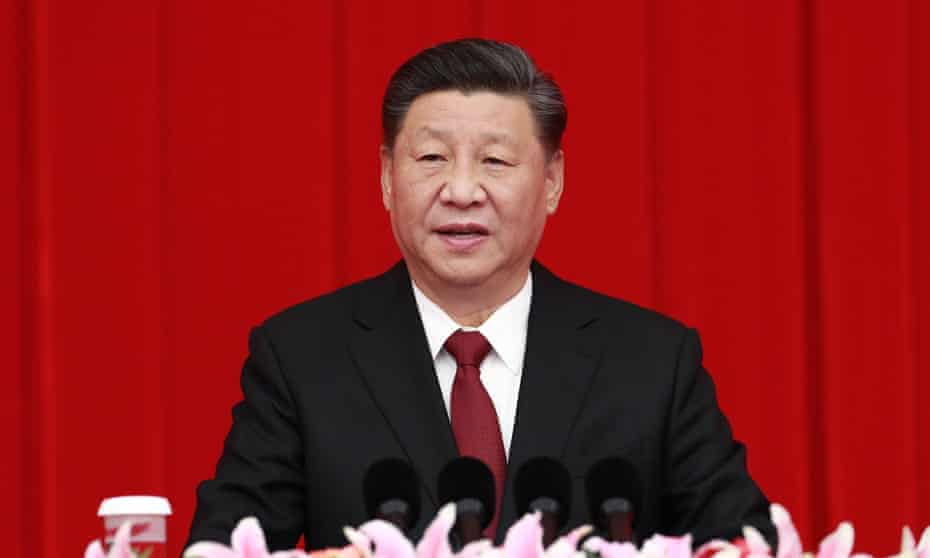

If one word could sum up the experience of 2020, it would be disbelief. Between Xi Jinping’s public acknowledgment of the coronavirus outbreak on 20 January 2020, and Joe Biden’s inauguration as the 46th president of the United States precisely a year later, the world was shaken by a disease that in the space of 12 months killed more than 2.2 million people and rendered tens of millions severely ill. Today the official death tolls stands at 4.51 million. The likely figure for excess deaths is more than twice that number. The virus disrupted the daily routine of virtually everyone on the planet, stopped much of public life, closed schools, separated families, interrupted travel and upended the world economy.

To contain the fallout, government support for households, businesses and markets took on dimensions not seen outside wartime. It was not just by far the sharpest economic recession experienced since the second world war, it was qualitatively unique. Never before had there been a collective decision, however haphazard and uneven, to shut large parts of the world’s economy down. It was, as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) put it, “a crisis like no other”.

Even before we knew what would hit us, there was every reason to think that 2020 might be tumultuous. The conflict between China and the US was boiling up. A “new cold war” was in the air. Global growth had slowed seriously in 2019. The IMF worried about the destabilising effect that geopolitical tension might have on a world economy that was already piled high with debt. Economists cooked up new statistical indicators to track the uncertainty that was dogging investment. The data strongly suggested that the source of the trouble was in the White House. The US’s 45th president, Donald Trump, had succeeded in turning himself into an unhealthy global obsession. He was up for reelection in November and seemed bent on discrediting the electoral process even if it yielded a win. Not for nothing, the slogan of the 2020 edition of the Munich Security Conference – the Davos for national security types – was “Westlessness”.

Apart from the worries about Washington, the clock on the Brexit negotiations was running out. Even more alarming for Europe as 2020 began was the prospect of a new refugee crisis. In the background lurked both the threat of a final grisly escalation in Syria’s civil war and the chronic problem of underdevelopment. The only way to remedy that was to energise investment and growth in the global south. The flow of capital, however, was unstable and unequal. At the end of 2019, half the lowest-income borrowers in sub-Saharan Africa were already approaching the point at which they could no longer service their debts.

The pervasive sense of risk and anxiety that hung around the world economy was a remarkable reversal. Not so long before, the west’s apparent triumph in the cold war, the rise of market finance, the miracles of information technology, and the widening orbit of economic growth appeared to cement the capitalist economy as the all-conquering driver of modern history. In the 1990s, the answer to most political questions had seemed simple: “It’s the economy, stupid.” As economic growth transformed the lives of billions, there was, Margaret Thatcher liked to say, “no alternative”. That is, there was no alternative to an order based on privatisation, light-touch regulation and the freedom of movement of capital and goods. As recently as 2005, Britain’s centrist prime minister Tony Blair could declare that to argue about globalisation made as much sense as arguing about whether autumn should follow summer.

By 2020, globalisation and the seasons were very much in question. The economy had morphed from being the answer to being the question. A series of deep crises – beginning in Asia in the late 90s and moving to the Atlantic financial system in 2008, the eurozone in 2010 and global commodity producers in 2014 – had shaken confidence in market economics. All those crises had been overcome, but by government spending and central bank interventions that drove a coach and horses through firmly held precepts about “small government” and “independent” central banks. The crises had been brought on by speculation, and the scale of the interventions necessary to stabilise them had been historic. Yet the wealth of the global elite continued to expand. Whereas profits were private, losses were socialised. Who could be surprised, many now asked, if surging inequality led to populist disruption? Meanwhile, with China’s spectacular ascent, it was no longer clear that the great gods of growth were on the side of the west.

And then, in January 2020, the news broke from Beijing. China was facing a full-blown epidemic of a novel coronavirus. This was the natural “blowback” that environmental campaigners had long warned us about, but whereas the climate crisis caused us to stretch our minds to a planetary scale and set a timetable in terms of decades, the virus was microscopic and all-pervasive, and was moving at a pace of days and weeks. It affected not glaciers and ocean tides, but our bodies. It was carried on our breath. It would put not just individual national economies but the world’s economy in question.

As it emerged from the shadows, Sars-CoV-2 had the look about it of a catastrophe foretold. It was precisely the kind of highly contagious, flu-like infection that virologists had predicted. It came from one of the places they expected it to come from – the region of dense interaction between wildlife, agriculture and urban populations sprawled across east Asia. It spread, predictably, through the channels of global transport and communication. It had, frankly, been a while coming.

There have been far more lethal pandemics. What was dramatically new about coronavirus in 2020 was the scale of the response. It was not just rich countries that spent enormous sums to support citizens and businesses – poor and middle-income countries were willing to pay a huge price, too. By early April, the vast majority of the world outside China, where it had already been contained, was involved in an unprecedented effort to stop the virus. “This is the real first world war,” said Lenín Moreno, president of Ecuador, one of the hardest-hit countries. “The other world wars were localised in [some] continents with very little participation from other continents … but this affects everyone. It is not localised. It is not a war from which you can escape.”

Lockdown is the phrase that has come into common use to describe our collective reaction. The very word is contentious. Lockdown suggests compulsion. Before 2020, it was a term associated with collective punishment in prisons. There were moments and places where that is a fitting description for the response to Covid. In Delhi, Durban and Paris, armed police patrolled the streets, took names and numbers, and punished those who violated curfews. In the Dominican Republic, an astonishing 85,000 people, almost 1% of the population, were arrested for violating the lockdown.

Even if no violence was involved, a government-mandated closure of all eateries and bars could feel repressive to their owners and clients. But lockdown seems a one-sided way of describing the economic reaction to the coronavirus. Mobility fell precipitately, well before government orders were issued. The flight to safety in financial markets began in late February. There was no jailer slamming the door and turning the key; rather, investors were running for cover. Consumers were staying at home. Businesses were closing or shifting to home working. By mid-March, shutting down became the norm. Those who were outside national territorial space, like hundreds of thousands of seafarers, found themselves banished to a floating limbo.

President Xi Jinping in January 2020. Photograph: Nareshkumar Shaganti/Alamy

President Xi Jinping in January 2020. Photograph: Nareshkumar Shaganti/AlamyThe widespread adoption of the term “lockdown” is an index of how contentious the politics of the virus would turn out to be. Societies, communities and families quarrelled bitterly over face masks, social distancing and quarantine. The entire experience was an example on the grandest scale of what the German sociologist Ulrich Beck in the 80s dubbed “risk society”. As a result of the development of modern society, we found ourselves collectively haunted by an unseen threat, visible only to science, a risk that remained abstract and immaterial until you fell sick, and the unlucky ones found themselves slowly drowning in the fluid accumulating in their lungs.

One way to react to such a situation of risk is to retreat into denial. That may work. It would be naive to imagine otherwise. Many pervasive diseases and social ills, including many that cause loss of life on a large scale, are ignored and naturalised, treated as “facts of life”. With regard to the largest environmental risks, notably the climate crisis, one might say that our normal mode of operation is denial and willful ignorance on a grand scale.

Facing up to the pandemic was what the vast majority of people all over the world tried to do. But the problem, as Beck said, is that getting to grips with the really large-scale, all-pervasive risks that modern society generates is easier said than done. It requires agreement on what the risk is. It also requires critical engagement with our own behaviour, and with the social order to which it belongs. It requires a willingness to make political choices about resource distribution and priorities at every level. Such choices clash with the prevalent desire of the last 40 years to depoliticise, to use markets or the law to avoid such decisions. This is the basic thrust behind neoliberalism, or the market revolution – to depoliticise distributional issues, including the very unequal consequences of societal risks, whether those be due to structural change in the global division of labour, environmental damage, or disease.

Coronavirus glaringly exposed our institutional lack of preparation, what Beck called our “organised irresponsibility”. It revealed the weakness of basic apparatuses of state administration, like up-to-date government databases. To face the crisis, we needed a society that gave far greater priority to care. Loud calls issued from unlikely places for a “new social contract” that would properly value essential workers and take account of the risks generated by the globalised lifestyles enjoyed by the most fortunate.

It fell to governments mainly of the centre and the right to meet the crisis. Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Donald Trump in the US experimented with denial. In Mexico, the notionally leftwing government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador also pursued a maverick path, refusing to take drastic action. Nationalist strongmen such as Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Narendra Modi in India, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey did not deny the virus, but relied on their patriotic appeal and bullying tactics to see them through.

It was the managerial centrist types who were under most pressure. Figures like Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer in the US, or Sebastián Piñera in Chile, Cyril Ramaphosa in South Africa, Emmanuel Macron, Angela Merkel, Ursula von der Leyen and their ilk in Europe. They accepted the science. Denial was not an option. They were desperate to demonstrate that they were better than the “populists”.

To meet the crisis, very middle-of-the-road politicians ended up doing very radical things. Most of it was improvisation and compromise, but insofar as they managed to put a programmatic gloss on their responses – whether in the form of the EU’s Next Generation programme or Biden’s Build Back Better programme in 2020 – it came from the repertoire of green modernisation, sustainable development and the Green New Deal.

The result was a bitter historic irony. Even as the advocates of the Green New Deal, such as Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, had gone down to political defeat, 2020 resoundingly confirmed the realism of their diagnosis. It was the Green New Deal that had squarely addressed the urgency of environmental challenges and linked it to questions of extreme social inequality. It was the Green New Deal that had insisted that in meeting these challenges, democracies could not allow themselves to be hamstrung by conservative economic doctrines inherited from the bygone battles of the 70s and discredited by the financial crisis of 2008. It was the Green New Deal that had mobilised engaged young citizens on whom democracy, if it was to have a hopeful future, clearly depended.

The Green New Deal had also, of course, demanded that rather than endlessly patching a system that produced and reproduced inequality, instability and crisis, it should be radically reformed. That was challenging for centrists. But one of the attractions of a crisis was that questions of the long-term future could be set aside. The year 2020 was all about survival.

The immediate economic policy response to the coronavirus shock drew directly on the lessons of 2008. Government spending and tax cuts to support the economy were even more prompt. Central bank interventions were even more spectacular. These fiscal and monetary policies together confirmed the essential insights of economic doctrines once advocated by radical Keynesians and made newly fashionable by doctrines such as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). State finances are not limited like those of a household. If a monetary sovereign treats the question of how to organise financing as anything more than a technical matter, that is itself a political choice. As John Maynard Keynes once reminded his readers in the midst of the second world war: “Anything we can actually do we can afford.” The real challenge, the truly political question, was to agree what we wanted to do and to figure out how to do it.

Experiments in economic policy in 2020 were not confined to the rich countries. Enabled by the abundance of dollars unleashed by the Fed, but drawing on decades of experience with fluctuating global capital flows, many emerging market governments, in Indonesia and Brazil for instance, displayed remarkable initiative in response to the crisis. They put to work a toolkit of policies that enabled them to hedge the risks of global financial integration. Ironically, unlike in 2008, China’s greater success in virus control left its economic policy looking relatively conservative. Countries such as Mexico and India, where the pandemic spread rapidly but governments failed to respond with large-scale economic policy, looked increasingly out of step with the times. The year would witness the head-turning spectacle of the IMF scolding a notionally leftwing Mexican government for failing to run a large enough budget deficit.

It was hard to avoid the sense that a turning point had been reached. Was this, finally, the death of the orthodoxy that had prevailed in economic policy since the 80s? Was this the death knell of neoliberalism? As a coherent ideology of government, perhaps. The idea that the natural envelope of economic activity – whether the disease environment or climate conditions – could be ignored or left to markets to regulate was clearly out of touch with reality. So, too, was the idea that markets could self-regulate in relation to all conceivable social and economic shocks. Even more urgently than in 2008, survival dictated interventions on a scale last seen in the second world war.

All this left doctrinaire economists gasping for breath. That in itself is not surprising. The orthodox understanding of economic policy was always unrealistic. In reality, neoliberalism had always been radically pragmatic. Its real history was that of a series of state interventions in the interests of capital accumulation, including the forceful deployment of state violence to bulldoze opposition. Whatever the doctrinal twists and turns, the social realities with which the market revolution had been entwined since the 1970s all endured until 2020. The historic force that finally burst the dykes of the neoliberal order was not radical populism or the revival of class struggle – it was a plague unleashed by heedless global growth and the massive flywheel of financial accumulation.

In 2008, the crisis had been brought on by the overexpansion of the banks and the excesses of mortgage securitisation. In 2020, the coronavirus hit the financial system from the outside, but the fragility that this shock exposed was internally generated. This time it was not banks that were the weak link, but the asset markets themselves. The shock went to the very heart of the system, the market for American Treasuries, the supposedly safe assets on which the entire pyramid of credit is based. If that had melted down, it would have taken the rest of the world with it.

The scale of stabilising interventions in 2020 was impressive. It confirmed the basic insistence of the Green New Deal that if the will was there, democratic states did have the tools they needed to exercise control over the economy. This was, however, a double-edged realisation, because if these interventions were an assertion of sovereign power, they were driven by crisis. As in 2008, they served the interests of those who had the most to lose. This time, not just individual banks but entire markets were declared too big to fail. To break that cycle of crisis and stabilising, and to make economic policy into a true exercise in democratic sovereignty, would require root-and-branch reform. That would require a real power shift, and the odds were stacked against that.

The massive economic policy interventions of 2020, like those of 2008, were Janus-faced. On the one hand, their scale exploded the bounds of neoliberal restraint and their economic logic confirmed the basic diagnosis of interventionist macroeconomics back to Keynes. When an economy was spiralling into recession, one did not have to accept the disaster as a natural cure, an invigorating purge. Instead, prompt and decisive government economic policy could prevent the collapse and forestall unnecessary unemployment, waste and social suffering.

These interventions could not but appear as harbingers of a new regime beyond neoliberalism. On the other hand, they were made from the top down. They were politically thinkable only because there was no challenge from the left and their urgency was impelled by the need to stabilise the financial system. And they delivered. Over the course of 2020, household net worth in the US increased by more than $15tn. Yet that overwhelmingly benefited the top 1%, who owned almost 40% of all stocks. The top 10%, between them, owned 84%. If this was indeed a “new social contract”, it was an alarmingly one-sided affair.

Nevertheless, 2020 was a moment not just of plunder, but of reformist experimentation. In response to the threat of social crisis, new modes of welfare provision were tried out in Europe, the US and many emerging market economies. And in search of a positive agenda, centrists embraced environmental policy and the issue of the climate crisis as never before. Contrary to the fear that Covid-19 would distract from other priorities, the political economy of the Green New Deal went mainstream. “Green Growth”, “Build Back Better”, “Green Deal” – the slogans varied, but they all expressed green modernisation as the common centrist response to the crisis.

Seeing 2020 as a comprehensive crisis of the neoliberal era – with regard to its environmental, social, economic and political underpinnings – helps us find our historical bearings. Seen in those terms, the coronavirus crisis marks the end of an arc whose origin is to be found in the 70s. It might also be seen as the first comprehensive crisis of the age of the Anthropocene – an era defined by the blowback from our unbalanced relationship to nature.

The year 2020 exposed how dependent economic activity was on the stability of the natural environment. A tiny virus mutation in a microbe could threaten the entire world’s economy. It also exposed how, in extremis, the entire monetary and financial system could be directed toward supporting markets and livelihoods. This forced the question of who was supported and how – which workers, which businesses would receive what benefits or which tax break? These developments tore down partitions that had been fundamental to the political economy of the last half-century – lines that divided the economy from nature, economics from social policy and from politics per se. On top of that, there was another major shift, which in 2020 finally dissolved the underlying assumptions of the era of neoliberalism: the rise of China.

When in 2005 Tony Blair scoffed at critics of globalisation, it was their fears that he mocked. He contrasted their parochial anxieties to the modernising energy of Asian nations, for which globalisation offered a bright horizon. The global security threats that Blair recognised, such as Islamic terrorism, were nasty. But they had no hope of actually changing the status quo. Therein lay their suicidal, otherworldly irrationality. In the decade after 2008, it was that confidence in the robustness of the status quo that was lost.

Russia was the first to expose the fact that global economic growth might shift the balance of power. Fuelled by exports of oil and gas, Moscow re-emerged as a challenge to US hegemony. Putin’s threat, however, was limited. China’s was not. In December 2017, the US issued its new National Security Strategy, which for the first time designated the Indo-Pacific as the decisive arena of great power competition. In March 2019, the EU issued a strategy document to the same effect. The UK, meanwhile, performed an extraordinary about-face, from celebrating a new “golden era” of Sino-UK relations in 2015 to deploying an aircraft carrier to the South China Sea.

The military logic was familiar. All great powers are rivals, or at least so goes the logic of “realist” thinking. In the case of China, there was the added factor of ideology. In 2021, the CCP did something its Soviet counterpart never got to do: it celebrated its centenary. While since the 80s it had permitted market-driven growth and private capital accumulation, Beijing made no secret of its adherence to an ideological heritage that ran by way of Marx and Engels to Lenin, Stalin and Mao. Xi Jinping could hardly have been more emphatic about the need to cleave to this tradition, and no clearer in his condemnation of Mikhail Gorbachev for losing hold of the Soviet Union’s ideological compass. So the “new” cold war was really the “old” cold war revived, the cold war in Asia, the one that the west had in fact never won.

There were, however, two major differences dividing the past from the present. The first was the economy. China posed a threat as a result of the greatest economic boom in history. That had hurt some workers in the west in manufacturing, but businesses and consumers across the western world and beyond had profited immensely from China’s development, and stood to profit even more in future. That created a quandary. A revived cold war with China made sense from every vantage point except “the economy, stupid”.

The second fundamental novelty was the global environmental problem, and the role of economic growth in accelerating it. When global climate politics first emerged in its modern form in the 90s, the US was the largest and most recalcitrant polluter. China was poor and its emissions barely figured in the global balance. By 2020, China emitted more carbon dioxide than the US and Europe put together, and the gap was poised to widen at least for another decade. You could no more envision a solution to the climate problem without China than you could imagine a response to the risk of emerging infectious diseases. China was the most powerful incubator of both.

In 2020, the green modernisers of the EU were still trying to resolve this double dilemma in their strategic documents by defining China all at the same time as a systemic rival, a strategic competitor and a partner in dealing with the climate crisis. The Trump administration made life easier for itself by denying the climate problem. But Washington, too, was impaled on the horns of the economic dilemma – between ideological denunciation of Beijing, strategic calculation, long-term corporate investments in China and the president’s desire to strike a quick deal. This was an unstable combination, and in 2020 it tipped. China was redefined as a threat to the US, strategically and economically. In reaction, the intelligence, security and judicial branches of the American government declared economic war on China. By closing markets and blocking the export of microchips and the equipment to make microchips, they set out to sabotage the development of China’s hi-tech sector, the heart of any modern economy.

It was to a degree accidental that this escalation took place when it did. China’s rise was a long-term world historic shift. But Beijing’s success in handling the coronavirus and the assertiveness that it unleashed were a red flag to the Trump administration. Meanwhile, it was growing increasingly clear that the US’s continued global strength in finance, tech and military power rested on domestic feet of clay. As Covid-19 painfully exposed, the US health system was ramshackle and its domestic social safety net left tens of millions at risk of poverty. If Xi’s “China dream” came through 2020 intact, the same cannot be said for its American counterpart.

The general crisis of neoliberalism in 2020 thus had a specific and traumatic significance for the US – and for one part of the American political spectrum in particular. The Republican party and its nationalist and conservative constituencies suffered in 2020 what can best be described as an existential crisis, with profoundly damaging consequences for the American government, for the American constitution and for America’s relations with the wider world. This culminated in the extraordinary period between 3 November 2020 and 6 January 2021, in which Trump refused to concede electoral defeat, a large part of the Republican party actively supported an effort to overturn the election, the social crisis and the pandemic were left unattended to, and finally, on 6 January, the president and other leading figures in his party encouraged a mob invasion of the Capitol.

For good reason, this raises deep concerns about the future of American democracy. And there are elements on the far right of American politics that can fairly be described as fascistoid. But two basic elements were missing from the original fascist equation in the US in 2020. One is total war. Americans remember the civil war and imagine future civil wars to come. They have recently engaged in expeditionary wars that have blown back on American society in militarised policing and paramilitary fantasies. But total war reconfigures society in quite a different way. It constitutes a mass body, not the individualised commandos of 2020.

The other missing ingredient in the classic fascist equation is social antagonism – a threat from the left, whether imagined or real, to the social and economic status quo. As the constitutional storm clouds gathered in 2020, American business aligned massively and squarely against Trump. Nor were the major voices of corporate America afraid to spell out the business case for doing so, including shareholder value, the problems of running companies with politically divided workforces, the economic importance of the rule of law and, astonishingly, the losses in sales to be expected in the event of a civil war.

This alignment of money with democracy in the US in 2020 should be reassuring, but only up to a point. Consider for a second an alternative scenario. What if the virus had arrived in the US a few weeks sooner, the spreading pandemic had rallied mass support for Bernie Sanders and his call for universal health care, and the Democratic primaries had swept an avowed socialist to the head of the ticket rather than Joe Biden? It is not difficult to imagine a scenario in which the full weight of American business was thrown the other way, for all the same reasons, backing Trump in order to ensure that Sanders was not elected. And what if Sanders had in fact won a majority? Then we would have had a true test of the American constitution and the loyalty of the most powerful social interests to it. The fact that we have to contemplate such scenarios is indicative of the extremity of the polycrisis of 2020.

The election of Joe Biden and the fact that his inauguration took place at the appointed time on 21 January 2021 restored a sense of calm. But when Biden boldly declares that “America is back”, it has become increasingly clear that the next question we need to ask is: which America? And back to what? The comprehensive crisis of neoliberalism may have unleashed creative intellectual energy even at the once-dead centre of politics. But an intellectual crisis does not a new era make. If it is energising to discover that we can afford anything we can actually do, it also puts us on the spot. What can and should we actually do? Who, in fact, is the we?

As Britain, the US and Brazil demonstrate, democratic politics is taking on strange and unfamiliar new forms. Social inequalities are more, not less extreme. At least in the rich countries, there is no collective countervailing force. Capitalist accumulation continues in channels that continuously multiply risks. The principal use to which our newfound financial freedom has been put are more and more grotesque efforts at financial stabilisation. The antagonism between the west and China divides huge chunks of the world, as not since the cold war. And now, in the form of Covid, the monster has arrived. The Anthropocene has shown its fangs – on an as yet modest scale. Covid is far from being the worst of what we should expect – 2020 was not the full alert. If we are dusting ourselves off and enjoying the recovery, we should reflect. Around the world the dead are unnumbered, but our best guess puts the figure at 10 million. Thousands are dying every day. And 2020 was a wake-up call.