'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Manchester. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Manchester. Show all posts

Tuesday, 14 September 2021

Thursday, 19 August 2021

No surprise Leeds lost to Manchester United, just look at the wage bills

Although teams can often defy financial logic for a time, to move up a tier is incredibly difficult

The easy thing is to blame the manager. It has become football’s default response to any crisis. A team hits a poor run or loses a big game: get rid of the manager. As Alex Ferguson said as many as 14 years ago, we live in “a mocking culture” and reality television has fostered the idea people should be voted off with great regularity (that he was trying to defend Steve McClaren’s reign as England manager should not undermine the wider point).

Managers are expendable. Rejigging squads takes time and money and huge amounts of effort in terms of research and recruitment, whereas anybody can look at who is doing well in Portugal or Greece or the Championship and spy a potential messiah. Then there are the structural factors, the underlying economic issues it is often preferable to ignore because to acknowledge them is to accept how little agency the people we shout about every week really have in football.

That point reared its head after Manchester United’s 5-1 victory over Leeds on Saturday. There was plenty to discuss: are Leeds overreliant on Kalvin Phillips, who was absent? Why does Marcelo Bielsa’s version of pressing so often lead to heavy defeats? Can Mason Greenwood’s movement allow Ole Gunnar Solskjær to field Paul Pogba and Bruno Fernandes without sacrificing a holding midfielder and, if it does, what does that mean for Marcus Rashford?

Yet there was a weird strand of coverage that insisted Solskjær had somehow outwitted Bielsa, even in some quarters that Bielsa needed to be replaced if Leeds are to kick on. (They finished ninth last season with 59 points, the highest points total by a promoted club for two decades). A Bielsa meltdown is possible; they do happen and he has never managed a fourth season at a club. There should be some concern that, like last season, Leeds lost by four goals at Old Trafford, insufficient lessons were learned, even if Bielsa said this was a better performance. But fundamentally, Manchester United’s wage bill is five times that of Leeds.

Everton, who finished a place below Leeds last season, had a wage bill three times bigger. Of last season’s Premier League, only West Brom and Sheffield United had wage bills lower than that of Leeds. To have finished ninth is an extraordinary achievement and nobody should think to slip back three or four places this season would be a failure. Modern football is starkly stratified and although teams can often defy financial logic for a time, to move up a tier is incredibly difficult.

There is still a tendency to talk of a Big Six in English football and while it is true six clubs last season had a weekly wage bill in excess of £2.5m, it is also true that within that grouping there are three with clear advantages: Manchester City (who had kept their wage bill relatively low, although if they do add Harry Kane to Jack Grealish that would clearly change) and Chelsea because their funding is not reliant on footballing success, and Manchester United because of the legacy that has allowed them to attach their name to a preposterous range of products across the globe.

Mikel Arteta is struggling to revive Arsenal. Photograph: Tom Jenkins/The Guardian

Mikel Arteta is struggling to revive Arsenal. Photograph: Tom Jenkins/The Guardian

Liverpool can perhaps challenge for the title this season, but their wage spending is 74% of that of United. That they were as good as they were in the two seasons before last was remarkable, but last season showed how vulnerable a team like Liverpool can be to a couple of injuries. Similarly, Leicester’s two fifth-place finishes with the eighth-highest wage bill are a striking achievement, their decline towards the end of the past two seasons less the result of them bottling it or any sort of psychological failure than of the limitations of their squad being exposed.

Which brings us to the other two members of the Big Six: Arsenal and Tottenham. Spurs’ last game at White Hart Lane, in 2017, brought a 2-1 win over Manchester United that guaranteed they finished second. Since when Spurs have bought Davinson Sánchez, Lucas Moura, Serge Aurier, Fernando Llorente, Juan Foyth, Tanguy Ndombele, Steven Bergwijn, Ryan Sessegnon, Giovani Lo Celso, Cristian Romero and Bryan Gil, while United have bought, among others, Alexis Sánchez, Victor Lindelöf, Nemanja Matic, Romelu Lukaku, Fred, Daniel James, Aaron Wan-Bissaka, Bruno Fernandes, Harry Maguire, Donny van de Beek, Raphaël Varane and Jadon Sancho. Money may not be everything in football, but it does help.

The irony of the situation is that it was investment in the infrastructure that should allow Spurs to generate additional revenues and better develop their own talent (much cheaper than buying it) that led to the lack of investment in players largely responsible for the staleness resulting in Mauricio Pochettino’s departure. That Daniel Levy compounded the problem by appointing José Mourinho – acting like a big club as though to jolt them to the next level – should not obscure the fact that until that point he had pursued a ruthless and successful economic logic.

Arsenal had gone through a similar process the previous decade, investing heavily in a new stadium at the expense of the squad, only to discover that by the time it was ready the financial environment had changed and the petro-fuelled era had begun. It was easy after the timid performance against Brentford on Friday to blame Mikel Arteta and ask why he gets such an easy ride. For all that Arsenal have finished the past two seasons relatively well, that criticism will only increase if there are not signs the tanker is being turned round. But the gulf to the top of the table is vast and a desperation to bridge that has contributed to a bizarre transfer policy.

That does not mean managers are beyond reproach and limp displays like Arsenal’s deserve criticism. But equally we should probably remember that where a side finishes in the league has far more to do with economic strata than any of the individuals involved.

Manchester United’s Fred celebrates celebrates after completing Manchester United’s 5-1 victory over Leeds. Photograph: Jon Super/AP

Jonathan Wilson in The Guardian

Jonathan Wilson in The Guardian

The easy thing is to blame the manager. It has become football’s default response to any crisis. A team hits a poor run or loses a big game: get rid of the manager. As Alex Ferguson said as many as 14 years ago, we live in “a mocking culture” and reality television has fostered the idea people should be voted off with great regularity (that he was trying to defend Steve McClaren’s reign as England manager should not undermine the wider point).

Managers are expendable. Rejigging squads takes time and money and huge amounts of effort in terms of research and recruitment, whereas anybody can look at who is doing well in Portugal or Greece or the Championship and spy a potential messiah. Then there are the structural factors, the underlying economic issues it is often preferable to ignore because to acknowledge them is to accept how little agency the people we shout about every week really have in football.

That point reared its head after Manchester United’s 5-1 victory over Leeds on Saturday. There was plenty to discuss: are Leeds overreliant on Kalvin Phillips, who was absent? Why does Marcelo Bielsa’s version of pressing so often lead to heavy defeats? Can Mason Greenwood’s movement allow Ole Gunnar Solskjær to field Paul Pogba and Bruno Fernandes without sacrificing a holding midfielder and, if it does, what does that mean for Marcus Rashford?

Yet there was a weird strand of coverage that insisted Solskjær had somehow outwitted Bielsa, even in some quarters that Bielsa needed to be replaced if Leeds are to kick on. (They finished ninth last season with 59 points, the highest points total by a promoted club for two decades). A Bielsa meltdown is possible; they do happen and he has never managed a fourth season at a club. There should be some concern that, like last season, Leeds lost by four goals at Old Trafford, insufficient lessons were learned, even if Bielsa said this was a better performance. But fundamentally, Manchester United’s wage bill is five times that of Leeds.

Everton, who finished a place below Leeds last season, had a wage bill three times bigger. Of last season’s Premier League, only West Brom and Sheffield United had wage bills lower than that of Leeds. To have finished ninth is an extraordinary achievement and nobody should think to slip back three or four places this season would be a failure. Modern football is starkly stratified and although teams can often defy financial logic for a time, to move up a tier is incredibly difficult.

There is still a tendency to talk of a Big Six in English football and while it is true six clubs last season had a weekly wage bill in excess of £2.5m, it is also true that within that grouping there are three with clear advantages: Manchester City (who had kept their wage bill relatively low, although if they do add Harry Kane to Jack Grealish that would clearly change) and Chelsea because their funding is not reliant on footballing success, and Manchester United because of the legacy that has allowed them to attach their name to a preposterous range of products across the globe.

Mikel Arteta is struggling to revive Arsenal. Photograph: Tom Jenkins/The Guardian

Mikel Arteta is struggling to revive Arsenal. Photograph: Tom Jenkins/The GuardianLiverpool can perhaps challenge for the title this season, but their wage spending is 74% of that of United. That they were as good as they were in the two seasons before last was remarkable, but last season showed how vulnerable a team like Liverpool can be to a couple of injuries. Similarly, Leicester’s two fifth-place finishes with the eighth-highest wage bill are a striking achievement, their decline towards the end of the past two seasons less the result of them bottling it or any sort of psychological failure than of the limitations of their squad being exposed.

Which brings us to the other two members of the Big Six: Arsenal and Tottenham. Spurs’ last game at White Hart Lane, in 2017, brought a 2-1 win over Manchester United that guaranteed they finished second. Since when Spurs have bought Davinson Sánchez, Lucas Moura, Serge Aurier, Fernando Llorente, Juan Foyth, Tanguy Ndombele, Steven Bergwijn, Ryan Sessegnon, Giovani Lo Celso, Cristian Romero and Bryan Gil, while United have bought, among others, Alexis Sánchez, Victor Lindelöf, Nemanja Matic, Romelu Lukaku, Fred, Daniel James, Aaron Wan-Bissaka, Bruno Fernandes, Harry Maguire, Donny van de Beek, Raphaël Varane and Jadon Sancho. Money may not be everything in football, but it does help.

The irony of the situation is that it was investment in the infrastructure that should allow Spurs to generate additional revenues and better develop their own talent (much cheaper than buying it) that led to the lack of investment in players largely responsible for the staleness resulting in Mauricio Pochettino’s departure. That Daniel Levy compounded the problem by appointing José Mourinho – acting like a big club as though to jolt them to the next level – should not obscure the fact that until that point he had pursued a ruthless and successful economic logic.

Arsenal had gone through a similar process the previous decade, investing heavily in a new stadium at the expense of the squad, only to discover that by the time it was ready the financial environment had changed and the petro-fuelled era had begun. It was easy after the timid performance against Brentford on Friday to blame Mikel Arteta and ask why he gets such an easy ride. For all that Arsenal have finished the past two seasons relatively well, that criticism will only increase if there are not signs the tanker is being turned round. But the gulf to the top of the table is vast and a desperation to bridge that has contributed to a bizarre transfer policy.

That does not mean managers are beyond reproach and limp displays like Arsenal’s deserve criticism. But equally we should probably remember that where a side finishes in the league has far more to do with economic strata than any of the individuals involved.

Sunday, 24 December 2017

Who pays for Manchester City’s beautiful game?

Nick Cohen in The Guardian

Even though I come from the red side of Manchester, I want Manchester City to win every game they play now. Hoping City fail is like hoping a great singer’s voice cracks or prima ballerina’s tendons tear. Journalists have written and broadcast millions of words about the intensity of Manchester City’s game and the beauty of its movement. You watch and gasp as each perfect pass finds its man and each impossible move becomes possible after all.

Everything that can be said should have been said. But here are words you never hear on the BBC or Sky and hear only rarely from the best sports writers. Manchester City’s success is built on the labour extracted by the rulers of a modern feudal state. Sheikh Mansour, its owner, is the half-brother of Sheikh Khalifa, the absolute monarch of the United Arab Emirates: an accident of birth that has given him a mountain of cash and Manchester City the Premier League’s best players.

An absolute monarchy is merely a dictatorship decked in fine robes. The usual restrictions of free speech, a free press, the rule of law, an independent judiciary and democratic elections still apply in the Emirates federation of seven sultanates. Critics are as likely to disappear or be held without due process as they are in less glamorous destinations. The riches that supply Pep Guardiola’s £15m salary and ensure the £264m wage bill for the players is met on time do not just come from oil. The Emirate monarchies, Qatar and Saudi Arabia rely on a system of economic exploitation you struggle to find a precedent for.

In the UAE as a whole, only 13% of the population are full nationals. In the glittering tourist resort of Dubai, citizenship rises slightly to 15% and in the Abu Dhabi emirate to 20%, but everywhere a subclass of immigrants does the bulk of the work. The obvious comparison is with apartheid: Arab nationals sit at the top, white expats have some privileges, as the coloureds and Asians had in the last days of the South African regime, while the dirty work – from construction to cleaning – is done by despised immigrants from south Asia.

But comparisons with apartheid or the Israeli occupation of the West Bank or America’s old deep south miscarry because the Arab princelings import their working class rather than rule over subdued inhabitants. It’s like Spartans bringing in Helots. Or if images of stern Spartan militarists feel incongruous when imposed on the flabby bodies of Gulf aristocrats, Eloi importing Morlocks. Timid labour reforms are meant to have improved the lot of the serfs. In law, employers can no longer keep them in line with the threat of deportation to India or the Philippines if they do not please a capricious boss. In practice, absolute monarchies repress the lawyers and campaigners who might take up their cases. Now, as always, activists are silenced and workers fear the cost of speaking out.

You should be able to praise Manchester City’s football and condemn it owners. Or, if that is asking too much, you should at least be able to talk about its owners or mention the source of their wealth. If only in passing. If only the once. Instead, there is silence. With Mansour building a global consortium of clubs, Qataris owning Paris Saint-Germain and Emirate money poised to buy Newcastle United, rich dictatorial states are engaging in competitive conspicuous consumption. They are creating the world’s best clubs and may one day take them off into an oligarchs’ league. You are not “bringing politics into football” when you worry about Sheikh Mansour. You are recognising that the future of football is political.

The silence about the fate of the national game covers much of national life. Everywhere you look, you are struck by the arguments that are not being made.

Mainstream Conservatives refuse to join Tory rebels in speaking out against the dangers of Brexit. They like to boast that they are stable and commonsensical types, with no time for dangerous experiments. When confronted with the reckless nationalism of the Tory right, however, they prefer the safe option of keeping quiet until public opinion shifts. Many Labour MPs and leftwing journalists deplore Corbyn and the far left. I speak from experience when I say they talk with great eloquence in private, but will not utter a squeak of dissent in public until Corbyn’s popularity among party members falls. They, too, will speak out when, and only when, they can be certain that it is too late for speaking out to make a difference.

We think of ourselves as more liberated than our ancestors, but the same repressive mechanisms silence us. In the 18th and 19th centuries, few wanted to say that gorgeous stately homes and fine public buildings had been built because the British looted Indians and enslaved Africans. Today, it feels equally “inappropriate” – to use a modern word that stinks of Victorian prudery – to say that a beautiful football club has been built on the proceeds of exploitation.

Football supporters reserve their hatred for owners such as the Glazers, who bought Manchester United with borrowed money and siphoned off the club’s profits to pay down the debt. If billions are available to turn Manchester City or Paris Saint-Germain into world-class clubs, the fans do not care where the money came from. Nor do neutrals who love football for its own sake. For them, it is as miserablist to talk about Manchester City’s owners on Match of the Day as to talk about the factory farming of turkeys at the Christmas lunch table.

Honest sports writers fear the accusation that they are joyless puritan nags whose sole pleasure is ruining the pleasure of others. In Britain’s vacuous politics, Conservatives fear accusations of ignoring the will of the people on Brexit. Labour MPs fear their activists rather than their voters. In both the Tory and Labour cases, the worst that can happen to MPs is deselection. Mail or Express journalists who came out against Brexit would, I imagine, risk their jobs or being moved on to a different story. But no leftwing paper would sack a columnist who criticised Corbyn. The worst they would endure is frosty words from line managers and twaddle on Twitter.

We do not live in Abu Dhabi. The police do not pick up dissidents. Jailers don’t torture them. Yet peer pressure and trivial fears are enough to suppress necessary arguments. If you do not yet have a New Year resolution, it’s worth resolving to treat both with the contempt they deserve.

Thursday, 9 February 2017

How three students caused a global crisis in economics - A review of The Econocracy

Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

In the autumn of 2011, as the world’s financial system lurched from crash to crisis, the authors of this book began, as undergraduates, to study economics. While their lectures took place at the University of Manchester the eurozone was in flames. The students’ first term would last longer than the Greek government. Banks across the west were still on life support. And David Cameron was imposing on Britons year on year of swingeing spending cuts.

Joe Earle, centre, with the Post-Crash Economics Society at Manchester University. Photograph: Jon Super

The Econocracy makes three big arguments. First, economics has shoved its way into all aspects of our public life. Flick through any newspaper and you’ll find it is not enough for mental illness to cause suffering, or for people to enjoy paintings: both must have a specific cost or benefit to GDP. It is as if Gradgrind had set up a boutique consultancy, offering mandatory but spurious quantification for any passing cause.

Second, the economics being pushed is narrow and of recent invention. It sees the economy “as a distinct system that follows a particular, often mechanical logic” and believes this “can be managed using a scientific criteria”. It would not be recognised by Keynes or Marx or Adam Smith.

In the 1930s, economists began describing the economy as a unitary entity. For decades, Treasury officials produced forecasts in English. That changed only in 1961, when they moved to formal equations and reams of numbers. By the end of the 1970s, 99 organisations were generating projections for the UK economy. Forecasting had become a numerical alchemy: turning base human assumptions and frailty into the marketable gold of rigorous-seeming science.

By making their discipline all-pervasive, and pretending it is the physics of social science, economists have turned much of our democracy into a no-go zone for the public. This is the authors’ ultimate charge: “We live in a nation divided between a minority who feel they own the language of economics and a majority who don’t.”

This status quo works well for the powerful and wealthy and it will be fiercely defended. As Ed Miliband and Jeremy Corbyn have found, suggest policies that challenge the narrow orthodoxy and you will be branded an economic illiterate – even if they add up. Academics who follow different schools of economic thought are often exiled from the big faculties and journals.

The most devastating evidence in this book concerns what goes into making an economist. The authors analysed 174 economics modules for seven Russell Group universities, making this the most comprehensive curriculum review I know of. Focusing on the exams that undergraduates were asked to prepare for, they found a heavy reliance on multiple choice. The vast bulk of the questions asked students either to describe a model or theory, or to show how economic events could be explained by them. Rarely were they asked to assess the models themselves. In essence, they were being tested on whether they had memorised the catechism and could recite it under invigilation.

Critical thinking is not necessary to win a top economics degree. Of the core economics papers, only 8% of marks awarded asked for any critical evaluation or independent judgment. At one university, the authors write, 97% of all compulsory modules “entailed no form of critical or independent thinking whatsoever”.

The high priests of economics still hold power, but they no longer have legitimacy

Remember that these students shell out £9,000 a year for what is an elevated form of rote learning. Remember, too, that some of these graduates will go on to work in the City, handle multimillion pound budgets at FTSE businesses, head Whitehall departments, and set policy for the rest of us. Yet, as the authors write: “The people who are entrusted to run our economy are in almost no way taught to think about it critically.”

They aren’t the only ones worried. Soon after Earle and co started at university, the Bank of England held a day-long conference titled Are Economics Graduates Fit for Purpose?. Interviewing Andy Haldane, chief economist at the Bank of England, in 2014, I asked: what was the answer? There was an audible gulp, and a pause that lasted most of a minute. Finally, an answer limped out: “Not yet.”

The Manchester undergraduates were told by an academic that alternative approaches were as much use as a tobacco-smoke enema. Which is to say, he was as likely to take Friedrich Hayek or Joseph Schumpeter seriously as he was to blow smoke up someone’s arse.

The students’ entrepreneurialism is evident in this book. Packed with original research, it comes with pages of endorsements, evidently harvested by the students themselves, from Vince Cable to Noam Chomsky. Yet the text is rarely angry. Its tone is of a strained politeness, as if the authors were talking politics with a putative father-in-law.

More thoughtful academics have accepted the need for change – but strictly on their own terms, within the limits only they decide. That professional defensiveness has done them no favours. When Michael Gove compared economists to the scientists who worked for Nazi Germany and declared the “people of this country have had enough of experts”, he was shamelessly courting a certain type of Brexiter. But that he felt able to say it at all says a lot about how low the standing of economists has sunk.

The high priests of economics still hold power, but they no longer have legitimacy. In proving so resistant to serious reform, they have sent the message to a sceptical public that they are unreformable. Which makes The Econocracy a case study for the question we should all be asking since the crash: how, after all that, have the elites – in Westminster, in the City, in economics – stayed in charge?

In the autumn of 2011, as the world’s financial system lurched from crash to crisis, the authors of this book began, as undergraduates, to study economics. While their lectures took place at the University of Manchester the eurozone was in flames. The students’ first term would last longer than the Greek government. Banks across the west were still on life support. And David Cameron was imposing on Britons year on year of swingeing spending cuts.

Yet the bushfires those teenagers saw raging each night on the news got barely a mention in the seminars they sat through, they say: the biggest economic catastrophe of our times “wasn’t mentioned in our lectures and what we were learning didn’t seem to have any relevance to understanding it”, they write in The Econocracy. “We were memorising and regurgitating abstract economic models for multiple-choice exams.”

Part of this book describes what happened next: how the economic crisis turned into a crisis of economics. It deserves a good account, since the activities of these Manchester students rank among the most startling protest movements of the decade.

After a year of being force-fed irrelevancies, say the students, they formed the Post-Crash Economics Society, with a sympathetic lecturer giving them evening classes on the events and perspectives they weren’t being taught. They lobbied teachers for new modules, and when that didn’t work, they mobilised hundreds of undergraduates to express their disappointment in the influential National Student Survey. The economics department ended up with the lowest score of any at the university: the professors had been told by their pupils that they could do better.

The protests spread to other economics faculties – in Glasgow, Istanbul, Kolkata. Working at speed, students around the world published a joint letter to their professors calling for nothing less than a reformation of their discipline.

Economics has been challenged by would-be reformers before, but never on this scale. What made the difference was the crash of 2008. Students could now argue that their lecturers hadn’t called the biggest economic event of their lifetimes – so their commandments weren’t worth the stone they were carved on. They could also point to the way in which the economic model in the real world was broken and ask why the models they were using had barely changed.

The protests found an attentive audience among fellow undergraduates – the sort who in previous years would have kept their heads down and waited for the “milk round” to deliver an accountancy traineeship, but were now facing the prospect of hiring freezes, moving back home and paying off their giant student debt with poor wages.

I covered this uprising from the outset, and later served as an unpaid trustee for the network now called Rethinking Economics. To me, it has two key features in common with other social movements that sprang up in the aftermath of the banking crash. Like the Occupy protests, it was ultimately about democracy: who gets to have a say, and who gets silenced. It also shared with the student fees protests of 2010 deep discomfort at the state of modern British universities. What are supposed to be forums for speculative thought more often resemble costly finishing schools for the sons of Chinese communist party cadres and the daughters of wealthy Russians.

Much of the post-crash dissent has disintegrated into trace elements. A line can be drawn from Occupy to Bernie Sanders and Black Lives Matter; some of those undergraduates who were kettled by the police in 2010 are now signed-up Corbynistas. But the economics movement remains remarkably intact. Rethinking Economics has grown to 43 student campaigns across 15 countries, from America to China. Some of its alumni went into the civil service, where they have established an Exploring Economics network to push for alternative approaches to economics in policy making. There are evening classes, and then there is this book, which formalises and expands the case first made five years ago.

Part of this book describes what happened next: how the economic crisis turned into a crisis of economics. It deserves a good account, since the activities of these Manchester students rank among the most startling protest movements of the decade.

After a year of being force-fed irrelevancies, say the students, they formed the Post-Crash Economics Society, with a sympathetic lecturer giving them evening classes on the events and perspectives they weren’t being taught. They lobbied teachers for new modules, and when that didn’t work, they mobilised hundreds of undergraduates to express their disappointment in the influential National Student Survey. The economics department ended up with the lowest score of any at the university: the professors had been told by their pupils that they could do better.

The protests spread to other economics faculties – in Glasgow, Istanbul, Kolkata. Working at speed, students around the world published a joint letter to their professors calling for nothing less than a reformation of their discipline.

Economics has been challenged by would-be reformers before, but never on this scale. What made the difference was the crash of 2008. Students could now argue that their lecturers hadn’t called the biggest economic event of their lifetimes – so their commandments weren’t worth the stone they were carved on. They could also point to the way in which the economic model in the real world was broken and ask why the models they were using had barely changed.

The protests found an attentive audience among fellow undergraduates – the sort who in previous years would have kept their heads down and waited for the “milk round” to deliver an accountancy traineeship, but were now facing the prospect of hiring freezes, moving back home and paying off their giant student debt with poor wages.

I covered this uprising from the outset, and later served as an unpaid trustee for the network now called Rethinking Economics. To me, it has two key features in common with other social movements that sprang up in the aftermath of the banking crash. Like the Occupy protests, it was ultimately about democracy: who gets to have a say, and who gets silenced. It also shared with the student fees protests of 2010 deep discomfort at the state of modern British universities. What are supposed to be forums for speculative thought more often resemble costly finishing schools for the sons of Chinese communist party cadres and the daughters of wealthy Russians.

Much of the post-crash dissent has disintegrated into trace elements. A line can be drawn from Occupy to Bernie Sanders and Black Lives Matter; some of those undergraduates who were kettled by the police in 2010 are now signed-up Corbynistas. But the economics movement remains remarkably intact. Rethinking Economics has grown to 43 student campaigns across 15 countries, from America to China. Some of its alumni went into the civil service, where they have established an Exploring Economics network to push for alternative approaches to economics in policy making. There are evening classes, and then there is this book, which formalises and expands the case first made five years ago.

Joe Earle, centre, with the Post-Crash Economics Society at Manchester University. Photograph: Jon Super

The Econocracy makes three big arguments. First, economics has shoved its way into all aspects of our public life. Flick through any newspaper and you’ll find it is not enough for mental illness to cause suffering, or for people to enjoy paintings: both must have a specific cost or benefit to GDP. It is as if Gradgrind had set up a boutique consultancy, offering mandatory but spurious quantification for any passing cause.

Second, the economics being pushed is narrow and of recent invention. It sees the economy “as a distinct system that follows a particular, often mechanical logic” and believes this “can be managed using a scientific criteria”. It would not be recognised by Keynes or Marx or Adam Smith.

In the 1930s, economists began describing the economy as a unitary entity. For decades, Treasury officials produced forecasts in English. That changed only in 1961, when they moved to formal equations and reams of numbers. By the end of the 1970s, 99 organisations were generating projections for the UK economy. Forecasting had become a numerical alchemy: turning base human assumptions and frailty into the marketable gold of rigorous-seeming science.

By making their discipline all-pervasive, and pretending it is the physics of social science, economists have turned much of our democracy into a no-go zone for the public. This is the authors’ ultimate charge: “We live in a nation divided between a minority who feel they own the language of economics and a majority who don’t.”

This status quo works well for the powerful and wealthy and it will be fiercely defended. As Ed Miliband and Jeremy Corbyn have found, suggest policies that challenge the narrow orthodoxy and you will be branded an economic illiterate – even if they add up. Academics who follow different schools of economic thought are often exiled from the big faculties and journals.

The most devastating evidence in this book concerns what goes into making an economist. The authors analysed 174 economics modules for seven Russell Group universities, making this the most comprehensive curriculum review I know of. Focusing on the exams that undergraduates were asked to prepare for, they found a heavy reliance on multiple choice. The vast bulk of the questions asked students either to describe a model or theory, or to show how economic events could be explained by them. Rarely were they asked to assess the models themselves. In essence, they were being tested on whether they had memorised the catechism and could recite it under invigilation.

Critical thinking is not necessary to win a top economics degree. Of the core economics papers, only 8% of marks awarded asked for any critical evaluation or independent judgment. At one university, the authors write, 97% of all compulsory modules “entailed no form of critical or independent thinking whatsoever”.

The high priests of economics still hold power, but they no longer have legitimacy

Remember that these students shell out £9,000 a year for what is an elevated form of rote learning. Remember, too, that some of these graduates will go on to work in the City, handle multimillion pound budgets at FTSE businesses, head Whitehall departments, and set policy for the rest of us. Yet, as the authors write: “The people who are entrusted to run our economy are in almost no way taught to think about it critically.”

They aren’t the only ones worried. Soon after Earle and co started at university, the Bank of England held a day-long conference titled Are Economics Graduates Fit for Purpose?. Interviewing Andy Haldane, chief economist at the Bank of England, in 2014, I asked: what was the answer? There was an audible gulp, and a pause that lasted most of a minute. Finally, an answer limped out: “Not yet.”

The Manchester undergraduates were told by an academic that alternative approaches were as much use as a tobacco-smoke enema. Which is to say, he was as likely to take Friedrich Hayek or Joseph Schumpeter seriously as he was to blow smoke up someone’s arse.

The students’ entrepreneurialism is evident in this book. Packed with original research, it comes with pages of endorsements, evidently harvested by the students themselves, from Vince Cable to Noam Chomsky. Yet the text is rarely angry. Its tone is of a strained politeness, as if the authors were talking politics with a putative father-in-law.

More thoughtful academics have accepted the need for change – but strictly on their own terms, within the limits only they decide. That professional defensiveness has done them no favours. When Michael Gove compared economists to the scientists who worked for Nazi Germany and declared the “people of this country have had enough of experts”, he was shamelessly courting a certain type of Brexiter. But that he felt able to say it at all says a lot about how low the standing of economists has sunk.

The high priests of economics still hold power, but they no longer have legitimacy. In proving so resistant to serious reform, they have sent the message to a sceptical public that they are unreformable. Which makes The Econocracy a case study for the question we should all be asking since the crash: how, after all that, have the elites – in Westminster, in the City, in economics – stayed in charge?

The Econocracy is published by Manchester University.

Saturday, 10 May 2014

University economics teaching isn't an education: it's a £9,000 lobotomy

Economics took a battering after the financial crisis, but faculties are refusing to teach alternative views. It's as if there's only one way to run an economy

The Post-Crash Economics Society at Manchester University has arranged an evening class on bubbles, panics and crashes. Photograph: Jon Super for the Guardian

"I don't care who writes a nation's laws – or crafts its treatises – if I can write its economics textbooks," said Paul Samuelson. The Nobel prizewinner grasped that what was true of gadgets was also true for economies: he who produces the instruction manual defines how the object will be used, and to what ends.

Samuelson's axiom held good until the collapse of Lehman Brothers, which triggered both an economic crisis and a crisis in economics. In the six years since, the reputations of those high priests of capitalism, academic economists, have taken a battering.

The Queen herself asked why hardly any of them saw the crash coming, while the Bank of England's Andy Haldane has noted how it rendered his colleagues' enchantingly neat models as good as useless: "The economy in crisis behaved more like slime descending a warehouse wall than Newton's pendulum." And this week, economics students from Kolkata to Manchester have gone on the warpath demanding radical changes in what they're taught.

In a manifesto signed by 42 university economics associations from 19 countries, the students decry a "dramatic narrowing of the curriculum" that presents the economy "in a vacuum". The result is that the generation next in line to run our economy, from Whitehall departments or corporate corner-offices, discuss policy without touching on "broader social impacts and moral implications of economic decisions".

The problem is summed up by one of the manifesto's coordinators, Faheem Rokadiya, at the University of Glasgow: "Whenever I sit an economics exam, I have to turn myself into a robot." But he and his fellow reformers aren't seeking to skimp on algebra, or calling for a bonfire of the works of the Chicago school. They simply object to the notion that there is one true way to do economics, especially after that apparently scientific method has been found so badly wanting.

In their battle to open up economics, Rokadiya et al have one hell of a fight on their hands, for the same reason that it has proved so hard to democratise so many aspects of the post-crash order: the forces of conservatism are just too powerful. To see how fiercely the academics fight back, take a look at the University of Manchester.

Since last autumn, members of the university's Post-Crash Economics Society have been campaigning for reform of their narrow syllabus. They've put on their own lectures from non-mainstream, heterodox economists, even organising evening classes on bubbles, panics and crashes. You might think academics would be delighted to see such undergraduate engagement, or that economists would be swift to respond to the market.

Not a bit of it. Manchester's economics faculty recently announced that it wouldn't renew the contract of the temporary lecturer of the bubbles course, and that students who wanted to learn about the crash would have to go to the business school.

The most significant economics event of our lifetime isn't being taught in any depth at one of the largest economics faculties in the country. So what exactly is a Russell Group university teaching our future economists? Last month the Post-Crash members published a report on the deficiencies of the teaching they receive. It is thorough and thoughtful, and reports: "Tutorials consist of copying problem sets off the board rather than discussing economic ideas, and 18 out of 48 modules have 50% or more marks given by multiple choice." Students point out that they are trained to digest economic theory and regurgitate it in exams, but never to question the assumptions that underpin it. This isn't an education: it's a nine-grand lobotomy.

The Manchester example is part of a much broader trend in which non-mainstream economists have been evicted from economics faculties and now hole up in geography departments or business schools. "Intellectual talibanisation" is how one renowned economist describes it in private. This isn't just bad for academia: the logical extension of the argument that you can only study economics in one way is that you can only run the economy in one way.

Mainstream economics still has debates, but they tend to be technical in nature. The Nobel prizewinner Paul Krugman has pointed to the recent work of Thomas Piketty as proof that mainstream economics is plenty wide-ranging enough. Yet when Piketty visited the Guardian last week, he complained that economists generate "sophisticated models with very little or no empirical basis … there's a lot of ideology and self-interest".

Like so many other parts of the post-crash order, mainstream economists are liberal in theory but can be authoritarian in practice. The reason for that is brilliantly summed up by that non-economist Upton Sinclair: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it."

Wednesday, 7 May 2014

Uefa and Michel Platini are missing the real targets with their £50 million fine for Manchester City

Paul Hayward in The Telegraph

When Abu Dhabi’s rulers first decided to build a bonfire of hundreds of millions of pounds at Manchester City they would have laughed at the idea that blowing money was a crime punishable by Uefa sanctions. Imagine that: a sport where they throw a £50 million penalty at you for excessive generosity.

Strictly, Financial Fair Play (FFP) is an anti-subsidy initiative by a game that prostrates itself to foreign billionaires and then ticks them off for investing too much. It defiles the World Cup by awarding it to Qatar, then disapproves of Qatari spending at Paris St-Germain.

It says little about rampant ticket price inflation, the huge sums extracted by agents or grotesque individual player salaries. Whichever way you turn it, Uefa’s clumsy lunge at “fairness” has ended up being about two gulf states who jumped into football as an act of future-proofing because their oil was running out.

No torch is being held here for sovereign wealth. But the distortion of the London house market by foreign speculators, for example, is a far more serious issue than City paying Sergio Agüero’s wages via a so-called sweetheart deal with Etihad Airways.

Uefa-ologists might have spotted that president Michel Platini enjoys a cosy relationship with Qatar, who chose Paris as their investment outlet, and that it might have been somewhat awkward for Europe’s governing body to punish PSG without also directing their disapproval at City.

The clubs hit hardest by these arbitrary actions are those who had to spend heavily to raise underperforming clubs into the elite. City and PSG both fit this profile.

It was no surprise, then, to find Roman Abramovich broadly supportive of the FFP principle. Chelsea’s owner had already torched the kind of cash City and PSG have burned in the last three years. By endorsing the move to have such extravagance cast as a crime, Abramovich was simply blocking the way to new tycoons and therefore protecting his competitive advantage.

From Sheikh Mansour of Abu Dhabi’s viewpoint, a £50 million fine doubtless leaves a kind of moral stain. It implies financial doping, or even cheating, with its suggestion that the £35 million-a-year Etihad deal was really a polite way to cook the books.

As with PSG and the Qatari tourist board (£167 million), Uefa clearly believe that the deal was inflated to allow one part of an oil-rich state to subsidise another. And they might be right.

Yet the people who struck those deals are unlikely to appreciate being singled out in an industry that is synonymous with creative accounting. If in doubt, consider the mess Barcelona got themselves into over Neymar.

Nobody wants an unregulated free for all, or illegality, or the crushing of the poor by the rich. But Uefa’s punishment of City takes no account of the direction in which the club is heading or the socially constructive investment in the Etihad Campus in a deprived part of Manchester. Shiekh Mansour and his entourage are not philanthropists, but nor does their spending fit the template of outright decadence.

So far all that expenditure has bought them one Premier League title and not much headway in Europe. There is no wholesale buying of trophies because the Premier League is too competitive to allow it. This season City have had to fight Liverpool and Chelsea for the championship. The seductive allure of FFP is that helps the poorer against the richer. All it might do in this case is to make Abu Dhabi resent being stigmatised and cause them to question Uefa’s motives. You can see the speech bubble now: “They take our money and then fine us for giving it to them?”

A much greater problem, certainly in England, is clubs being ram-raided by speculators who seek to suck money out, not put it in. Portsmouthand Birmingham City are just two examples of clubs that have been treated like lumps of meat on an “investment” menu.

Many of us would like to see regulation attack that issue before the Uefa bureaucracy drives through arbitrary penalties against a club (City) who are putting money in, rather than taking it out, however vulgar it might sometimes seem.

Where is the £50 million fine for the Glazers for servicing their debts from Manchester United’s revenues? On this evidence, FFP is mere grandstanding.

Tuesday, 10 December 2013

David Moyes, just like John Major, is destined to fail

Sport is no different from politics. There is a syndrome that means it's all but impossible for one star to follow another

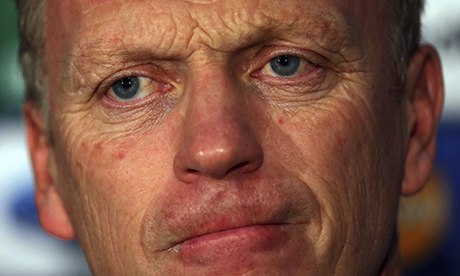

Manchester United manager David Moyes is discovering how hard it is to follow a predecessor of star quality Photograph: Dave Thompson/PA

You don't have to be a football fan to understand the trouble with David Moyes. Anyone familiar with the highest reaches of politics will recognise his predicament immediately. For those who turn rarely to the back pages, Moyes is in his first season as the manager of Manchester United. He inherited a team that had just won yet another title as Premier League champions, but under him they are struggling. Now ninth in the league, they are a full 13 points off the top spot. What's more, Moyes has broken a few awkward records. Under him, the team have lost at home to Everton (his old club) for the first time in 21 years and on Saturday lost to Newcastle at Old Trafford for the first time since 1972. Tonight another unwanted feat threatens. If they lose to the Ukrainian team Shakhtar Donetsk, it will be the first time United have suffered three successive home defeats in 50 years.

Watch Moyes attempt to explain these results, or defend his performance, in a post-match interview or press conference and, if you're a political anorak, you instantly think of one man: John Major. Or, if you're an American, perhaps the first George Bush. For what you are witnessing is a classic case of a syndrome that recurs in politics: the pale successor fated to follow a charismatic leader and forever doomed by the comparison.

Major may be earning some late kudos and revision of his reputation now, but while prime minister he was in the permanent shadow of his predecessor, Margaret Thatcher. Bush the elder was always going to be dull after the man who went before him, Ronald Reagan. So it is with Moyes, who was given the hardest possible act to follow – inheriting from one of the footballing greats, Sir Alex Ferguson.

It's a pattern that recurs with near-universal regularity. Tony Blair was prime minister for 10 years; Gordon Brown never hit the same heights and only managed three. Same with Jean Chrétien of Canada and his luckless successor Paul Martin. Or, fitting for this day, consider the case of Thabo Mbeki whose destiny was to be the man who took over from Nelson Mandela and so was all but preordained to be a disappointment.

It's as if an almost Newtonian law applies: the charisma of a leader exists in inverse proportion to the charisma of his or her predecessor. Moyes is only the latest proof.

What could explain the syndrome? Does nature abhor one star following another in immediate succession?

One theory suggests itself, though it draws more from psychology than physics. Note the role, direct or indirect, many of these great leaders had in choosing their successors. Could it be that some part of them actually wanted a lacklustre heir, all the better to enhance their own reputation? United could have had any one of the biggest, most glamorous names in football at the helm, yet Ferguson handpicked Moyes. Did Sir Alex do that to ensure he would look even better?

For this is how it works. Once the great man or woman has gone, and everything falls apart, their apparent indispensability becomes all the harder to deny. Manchester United fans look at the same players who were champions a few months ago, now faring so badly, and conclude: Ferguson was the reason we won.

If that was his unconscious purpose in picking the former Everton boss, then Sir Alex chose very wisely. And Moyes can comfort himself that, in this regard at least – like Major, Bush, Brown and so many others before him – he's doing his job perfectly.

Wednesday, 19 October 2011

In the Premier League the endgame of rampant capitalism is being played out

An unsustainable system where the rich win and the poor go to the wall. We see it in English football – and beyond

Illustration by Belle Mellor

It's a newspaper convention that the front and back pages are a

world apart, as if news and sport inhabit two different spheres with

little to say to each other. Indeed, it used to be an article of faith

that "sport and politics don't mix", with the former no more than a form

of escapism from the latter. And yet the Occupy Wall Street and London Stock Exchange

protests that led the weekend news bulletins might not be entirely

unrelated to the Premier League results that closed them. For the

current state of our football sheds a rather revealing light on the

current state of both our politics and our economy. Or, as one sage of

the sport puts it: "As ever, the national game reflects the nation's

times."

What that reflection says is that Britain, or England, has become the home of a turbo-capitalism that leaves even the land of the let-it-rip free market – the United States – for dust. If capitalism is often described metaphorically as a race in which the richest always win, football has turned that metaphor into an all too literal reality.

Let's take as our text a series of reports written by the sage just quoted, namely the Guardian's David Conn, who has carved a unique niche investigating the politics and commercialisation of football. Conn elicited a candid admission from the new American owners of Liverpool Football Club, who confessed that part of the lure of buying a stake in what they called the "EPL" – the English Premier League – was that they get to keep all the money they make, rather than having to share it as they would have to under the – their phrase – "very socialistic" rules that operate in US sport. In other words, England has become a magnet for those drawn to behave in a way they couldn't get away with at home.

Start with first principles. Of course, inequality is built into sport: some people are simply stronger or faster than others. What makes sport compelling is watching closely matched individuals or teams compete to come out on top.

But a different kind of inequality matters too: money. A rich club can buy up all the best players and win every time. That's the story of today's Premier League, as super-flush Manchester United sweep all before them, challenged only by local rivals Manchester City – now endowed by an oil billionaire – and Chelsea, funded to the hilt by a Russian oligarch. This, then, becomes a different kind of competition, a battle not of skill, pace and temperament but of pounds, shillings and pence. The clearest manifestation of that came at the close of the transfer window, when the biggest teams splashed out millions to buy the top talent. It means the half-dozen top sides, already at a different level from the rest, soared even higher towards the stratosphere and out of reach – in just the same way that the super-rich float ever further away from everyone else, the 1% in a different league from the 99%, as the Occupy protesters would put it.

Nothing you can do about that, says dogmatic capitalism. You can no more stop the richest teams dominating football than you can prevent the fastest sprinter winning gold. That's the force of the market, all but a law of nature.

Except along comes American sport to show us another way. First, there are those rules on revenue-sharing that so frustrated Liverpool's new owners. All the money that, say, a baseball team makes – from tickets, TV rights and merchandise – is taxed by the major league that runs the sport and spread around the other clubs, so that the richest cannot dwarf the rest. That isn't because the titans of Major League Baseball have read too much Marx. It's because they understand that their sport is worth nothing if it stops being a real competition, if only a handful of the wealthiest teams ever have a chance of winning. Redistributing the wealth around the league ensures their sport doesn't become boring. It does not level the playing field, but it comes very close.

The proof is in the stats so beloved of sporting obsessives. Over the past 19 seasons, 12 different teams have won baseball's biggest prize. In the 19 seasons since the Premier League was created, only four teams have won; Manchester United alone have won the title 12 of those 19 times.

It's not just revenue-sharing that ensures true competition. In American football and basketball a salary cap applies, limiting how much each club can pay in wages and thereby preventing the richest teams making their domination permanent by snapping up all the best players. (A "luxury tax" performs a similar function in baseball.) In the same spirit, teams in all major US sports submit to a "draft", in which they take turns picking from a pool of newly eligible players, so that the equivalent of Chelsea or Manchester City can't gobble up all the fresh talent, but instead have to let the Blackburns or Wigans have a go.

Put like that, it seems fantastical. Who can imagine Old Trafford voluntarily snaffling less of the pie, so that clubs in smaller cities with smaller grounds, and therefore weaker gate receipts, get a look in? And yet English football used to work just like that. When the founders of the Football League gathered in a Manchester hotel in 1888, they fretted over how they might ensure that a fixture between, say, Derby County and Everton remained a real contest. They agreed the home side should give a proportion of its takings to the visitors, a system that held firm till 1983.

Clubs shared the TV money when it came too, spreading it around all 92 league clubs. But the big teams always resented subsidising the minnows; indeed, the Premier League was formed out of the biggest 20 clubs' express desire to keep Rupert Murdoch's millions for themselves. That TV money is at least partly spread throughout the Premier League, but now there are noises about ending even that small nod towards wealth-sharing, so that the biggest half-dozen teams can keep every penny for themselves.

Not for the first time, it's fallen to Europe to act. Upcoming Uefa "financial fair play" rules will require teams to live within their earnings, which should put an end to the sugar daddy handouts of Man City and Chelsea. But that 2014 change will push clubs to maximise their revenue, which is bound, in turn, to mean even less sharing. Football will still be a game determined by who has most money.

There are three consequences of this strange gulf between our rules and those across the Atlantic. First, football's most storied clubs have become attractive to foreign tycoons who sniff a licence to print money, unrestricted. Second, we've established a model that is inherently unsustainable, involving colossal debts that cripple all those without a billionaire to bail them out. Since 1992, league clubs and one Premier League team – Portsmouth – have fallen insolvent 55 times. Third, we risk killing the golden goose, turning an activity that should be thrilling into a non-contest whose outcome is all but preordained.

Hmm, a system that sees our biggest names falling to leveraged takeovers – think Kraft's buy-up of Cadbury – thereby selling off the crown jewels of our collective culture in the name of a rampant capitalism that is both unsustainable and ultimately joyless. That doesn't just sound like the state of the national game, that sounds like the state of the nation.

What that reflection says is that Britain, or England, has become the home of a turbo-capitalism that leaves even the land of the let-it-rip free market – the United States – for dust. If capitalism is often described metaphorically as a race in which the richest always win, football has turned that metaphor into an all too literal reality.

Let's take as our text a series of reports written by the sage just quoted, namely the Guardian's David Conn, who has carved a unique niche investigating the politics and commercialisation of football. Conn elicited a candid admission from the new American owners of Liverpool Football Club, who confessed that part of the lure of buying a stake in what they called the "EPL" – the English Premier League – was that they get to keep all the money they make, rather than having to share it as they would have to under the – their phrase – "very socialistic" rules that operate in US sport. In other words, England has become a magnet for those drawn to behave in a way they couldn't get away with at home.

Start with first principles. Of course, inequality is built into sport: some people are simply stronger or faster than others. What makes sport compelling is watching closely matched individuals or teams compete to come out on top.

But a different kind of inequality matters too: money. A rich club can buy up all the best players and win every time. That's the story of today's Premier League, as super-flush Manchester United sweep all before them, challenged only by local rivals Manchester City – now endowed by an oil billionaire – and Chelsea, funded to the hilt by a Russian oligarch. This, then, becomes a different kind of competition, a battle not of skill, pace and temperament but of pounds, shillings and pence. The clearest manifestation of that came at the close of the transfer window, when the biggest teams splashed out millions to buy the top talent. It means the half-dozen top sides, already at a different level from the rest, soared even higher towards the stratosphere and out of reach – in just the same way that the super-rich float ever further away from everyone else, the 1% in a different league from the 99%, as the Occupy protesters would put it.

Nothing you can do about that, says dogmatic capitalism. You can no more stop the richest teams dominating football than you can prevent the fastest sprinter winning gold. That's the force of the market, all but a law of nature.

Except along comes American sport to show us another way. First, there are those rules on revenue-sharing that so frustrated Liverpool's new owners. All the money that, say, a baseball team makes – from tickets, TV rights and merchandise – is taxed by the major league that runs the sport and spread around the other clubs, so that the richest cannot dwarf the rest. That isn't because the titans of Major League Baseball have read too much Marx. It's because they understand that their sport is worth nothing if it stops being a real competition, if only a handful of the wealthiest teams ever have a chance of winning. Redistributing the wealth around the league ensures their sport doesn't become boring. It does not level the playing field, but it comes very close.

The proof is in the stats so beloved of sporting obsessives. Over the past 19 seasons, 12 different teams have won baseball's biggest prize. In the 19 seasons since the Premier League was created, only four teams have won; Manchester United alone have won the title 12 of those 19 times.

It's not just revenue-sharing that ensures true competition. In American football and basketball a salary cap applies, limiting how much each club can pay in wages and thereby preventing the richest teams making their domination permanent by snapping up all the best players. (A "luxury tax" performs a similar function in baseball.) In the same spirit, teams in all major US sports submit to a "draft", in which they take turns picking from a pool of newly eligible players, so that the equivalent of Chelsea or Manchester City can't gobble up all the fresh talent, but instead have to let the Blackburns or Wigans have a go.

Put like that, it seems fantastical. Who can imagine Old Trafford voluntarily snaffling less of the pie, so that clubs in smaller cities with smaller grounds, and therefore weaker gate receipts, get a look in? And yet English football used to work just like that. When the founders of the Football League gathered in a Manchester hotel in 1888, they fretted over how they might ensure that a fixture between, say, Derby County and Everton remained a real contest. They agreed the home side should give a proportion of its takings to the visitors, a system that held firm till 1983.

Clubs shared the TV money when it came too, spreading it around all 92 league clubs. But the big teams always resented subsidising the minnows; indeed, the Premier League was formed out of the biggest 20 clubs' express desire to keep Rupert Murdoch's millions for themselves. That TV money is at least partly spread throughout the Premier League, but now there are noises about ending even that small nod towards wealth-sharing, so that the biggest half-dozen teams can keep every penny for themselves.

Not for the first time, it's fallen to Europe to act. Upcoming Uefa "financial fair play" rules will require teams to live within their earnings, which should put an end to the sugar daddy handouts of Man City and Chelsea. But that 2014 change will push clubs to maximise their revenue, which is bound, in turn, to mean even less sharing. Football will still be a game determined by who has most money.

There are three consequences of this strange gulf between our rules and those across the Atlantic. First, football's most storied clubs have become attractive to foreign tycoons who sniff a licence to print money, unrestricted. Second, we've established a model that is inherently unsustainable, involving colossal debts that cripple all those without a billionaire to bail them out. Since 1992, league clubs and one Premier League team – Portsmouth – have fallen insolvent 55 times. Third, we risk killing the golden goose, turning an activity that should be thrilling into a non-contest whose outcome is all but preordained.

Hmm, a system that sees our biggest names falling to leveraged takeovers – think Kraft's buy-up of Cadbury – thereby selling off the crown jewels of our collective culture in the name of a rampant capitalism that is both unsustainable and ultimately joyless. That doesn't just sound like the state of the national game, that sounds like the state of the nation.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)