Sport is no different from politics. There is a syndrome that means it's all but impossible for one star to follow another

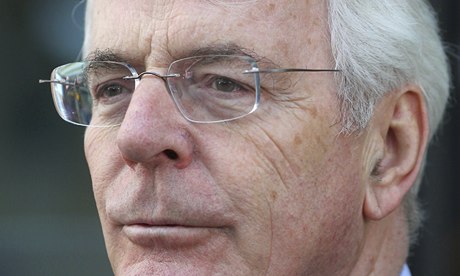

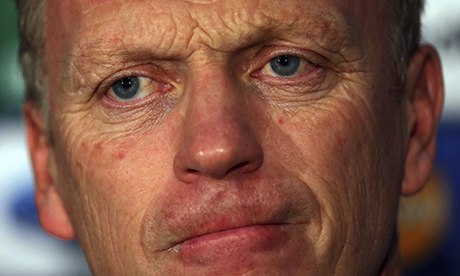

Manchester United manager David Moyes is discovering how hard it is to follow a predecessor of star quality Photograph: Dave Thompson/PA

You don't have to be a football fan to understand the trouble with David Moyes. Anyone familiar with the highest reaches of politics will recognise his predicament immediately. For those who turn rarely to the back pages, Moyes is in his first season as the manager of Manchester United. He inherited a team that had just won yet another title as Premier League champions, but under him they are struggling. Now ninth in the league, they are a full 13 points off the top spot. What's more, Moyes has broken a few awkward records. Under him, the team have lost at home to Everton (his old club) for the first time in 21 years and on Saturday lost to Newcastle at Old Trafford for the first time since 1972. Tonight another unwanted feat threatens. If they lose to the Ukrainian team Shakhtar Donetsk, it will be the first time United have suffered three successive home defeats in 50 years.

Watch Moyes attempt to explain these results, or defend his performance, in a post-match interview or press conference and, if you're a political anorak, you instantly think of one man: John Major. Or, if you're an American, perhaps the first George Bush. For what you are witnessing is a classic case of a syndrome that recurs in politics: the pale successor fated to follow a charismatic leader and forever doomed by the comparison.

Major may be earning some late kudos and revision of his reputation now, but while prime minister he was in the permanent shadow of his predecessor, Margaret Thatcher. Bush the elder was always going to be dull after the man who went before him, Ronald Reagan. So it is with Moyes, who was given the hardest possible act to follow – inheriting from one of the footballing greats, Sir Alex Ferguson.

It's a pattern that recurs with near-universal regularity. Tony Blair was prime minister for 10 years; Gordon Brown never hit the same heights and only managed three. Same with Jean Chrétien of Canada and his luckless successor Paul Martin. Or, fitting for this day, consider the case of Thabo Mbeki whose destiny was to be the man who took over from Nelson Mandela and so was all but preordained to be a disappointment.

It's as if an almost Newtonian law applies: the charisma of a leader exists in inverse proportion to the charisma of his or her predecessor. Moyes is only the latest proof.

What could explain the syndrome? Does nature abhor one star following another in immediate succession?

One theory suggests itself, though it draws more from psychology than physics. Note the role, direct or indirect, many of these great leaders had in choosing their successors. Could it be that some part of them actually wanted a lacklustre heir, all the better to enhance their own reputation? United could have had any one of the biggest, most glamorous names in football at the helm, yet Ferguson handpicked Moyes. Did Sir Alex do that to ensure he would look even better?

For this is how it works. Once the great man or woman has gone, and everything falls apart, their apparent indispensability becomes all the harder to deny. Manchester United fans look at the same players who were champions a few months ago, now faring so badly, and conclude: Ferguson was the reason we won.

If that was his unconscious purpose in picking the former Everton boss, then Sir Alex chose very wisely. And Moyes can comfort himself that, in this regard at least – like Major, Bush, Brown and so many others before him – he's doing his job perfectly.