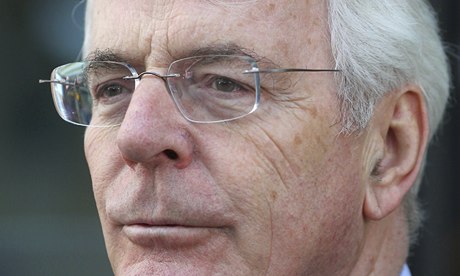

The former Prime Minister’s call for a one-off tax on the energy companies was eye-catching, but his broader argument was far more powerful. Without qualification, Major insisted that governments had a duty to intervene in failing markets. He made this statement as explicitly as Ed Miliband has done since the latter became Labour’s leader. The former Prime Minister disagrees with Miliband’s solution – a temporary price freeze – but he is fully behind the proposition that a government has a duty to act. He stressed that he was making the case as a committed Conservative.

Yet the proposition offends the ideological souls of those who currently lead the Conservative party. Today’s Tory leadership, the political children of Margaret Thatcher, is purer than the Lady herself in its disdain for state intervention. In developing his case, Major pointed the way towards a modern Tory party rather than one that looks to the 1980s for guidance. Yes, Tories should intervene in failing markets, but not in the way Labour suggests. He proposes a one-off tax on energy companies. At least he has a policy. In contrast, the generation of self-proclaimed Tory modernisers is paralysed, caught between its attachment to unfettered free markets and the practical reality that powerless consumers are being taken for a ride by a market that does not work.

Major went much further, outlining other areas in which the Conservatives could widen their appeal. They included the case for a subtler approach to welfare reform. He went as far as to suggest that some of those protesting at the injustice of current measures might have a point. He was powerful too on the impoverished squalor of some people’s lives, and on their sense of helplessness – suggesting that housing should be a central concern for a genuinely compassionate Conservative party. The language was vivid, most potently when Major outlined the choice faced by some in deciding whether to eat or turn the heating on. Every word was placed in the wider context of the need for the Conservatives to win back support in the north of England and Scotland.

Of course Major had an agenda beyond immediate politics. Former prime ministers are doomed to defend their record and snipe at those who made their lives hellish when they were in power. Parts of his speech inserted blades into old enemies. His record was not as good as he suggested, not least in relation to the abysmal state of public services by the time he left in 1997. But the period between 1990, when Major first became Prime Minister, and the election in 1992 is one that Tories should re-visit and learn from. Instead it has been virtually airbrushed out of their history.

In a very brief period of time Major and his party chairman Chris Patten speedily changed perceptions of their party after the fall of Margaret Thatcher. Major praised the BBC, spoke of the need to be at the heart of Europe while opting out of the single currency, scrapped the Poll Tax, placed a fresh focus on the quality of public services through the too easily derided Citizens’ Charter, and sought to help those on benefits or low incomes. As Neil Kinnock reflected later, voters thought there had been a change of government when Major replaced Thatcher, making it more difficult for Labour to claim that it was time for a new direction.

The key figures in the Conservative party were Major, Patten, Michael Heseltine, Ken Clarke and Douglas Hurd. Now it is Cameron, George Osborne, Michael Gove, William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith, Oliver Letwin and several others with similar views. They include Eurosceptics, plus those committed to a radical shrinking of the state and to transforming established institutions. All share a passion for the purity of markets in the public and private sectors. Yet in the Alice in Wonderland way in which politics is reported, the current leadership is portrayed as “modernisers” facing down “the Tory right”.

The degree to which the debate has moved rightwards at the top of the Conservative party and in the media can be seen from the bewildered, shocked reaction to Nick Clegg’s modest suggestion that teachers in free schools should be qualified to teach. The ideologues are so unused to being challenged they could not believe such comments were being made. Instead of addressing Clegg’s argument, they sought other reasons for such outrageous suggestions. Clegg was wooing Labour. Clegg was scared that his party would move against him. Clegg was seeking to woo disaffected voters. The actual proposition strayed well beyond their ideological boundaries.

This is why Major’s intervention has such an impact. He exposed the distorting way in which politics is currently reported. It is perfectly legitimate for the current Conservative leadership to seek to re-heat Thatcherism if it wishes to do so, but it cannot claim to be making a significant leap from the party’s recent past.

Nonetheless Cameron’s early attempts to embark on a genuinely modernising project are another reason why he and senior ministers should take note of what Major says. For leaders to retain authority and authenticity there has to be a degree of coherence and consistency of message. In his early years as leader, Cameron transmitted messages which had some similarities with Major’s speech, at least in terms of symbolism and tone. Cameron visited council estates, urged people to vote blue and to go green, spoke at trade union conferences rather than to the CBI, played down the significance of Europe as an issue, and was careful about how he framed his comments on immigration. If he enters the next election “banging on” about Europe, armed with populist policies on immigration while bashing “scroungers” on council estates and moaning about green levies, there will be such a disconnect with his earlier public self that voters will wonder about how substantial and credible he is.

Cameron faces a very tough situation, with Ukip breathing down his neck and a media urging him rightwards. But the evidence is overwhelming. The one-nation Major was the last Tory leader to win an overall majority. When Cameron affected a similar set of beliefs to Major’s, he was also well ahead in the polls. More recently the 80-year old Michael Heseltine pointed the way ahead with his impressive report on an active industrial strategy. Now Major, retired from politics, charts a credible route towards electoral recovery. How odd that the current generation of Tory leaders is more trapped by the party’s Thatcherite past than those who lived through it as ministers.