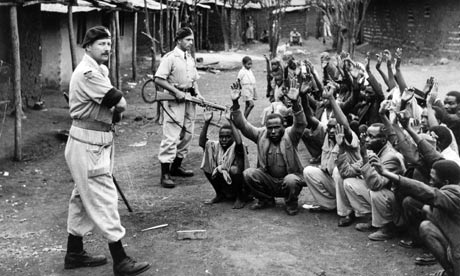

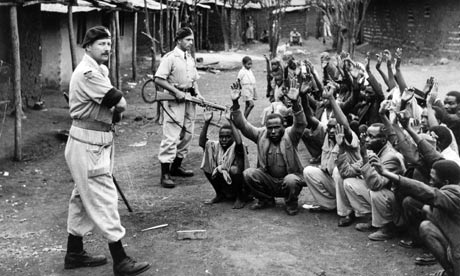

'Consider how Niall Ferguson deals with the Kenyan emergency: by suppressing it entirely in favour of a Kenyan idyll of 'our bungalow, our maid, our smattering of Swahili – and our sense of unshakeable security' in his book Empire.' Photograph: Popperfoto/Popperfoto/Getty Images

Scuttling away from India in 1947, after plunging the jewel in the crown into a

catastrophic partition, "the British", the novelist Paul Scott famously wrote, "came to the end of themselves as they were". The legacy of British rule, and the manner of their departures – civil wars and impoverished nation states locked expensively into antagonism, whether in the Middle East, Africa or the Malay Peninsula – was clearer by the time Scott completed his

Raj Quartet in the early 1970s. No more, he believed, could the British allow themselves any soothing illusions about the basis and consequences of their power.

Scott had clearly not anticipated the collective need to forget crimes and disasters. The Guardian reports that the British government is paying compensation to the nearly 10,000 Kenyans detained and tortured during the Mau Mau insurgency in the 1950s. In what has been described by the historian Caroline Elkins as Britain's own "Gulag", Africans resisting white settlers were roasted alive in addition to being hanged to death. Barack Obama's own grandfather had pins pushed into his fingers and his testicles squeezed between metal rods.

The British colonial government destroyed the evidence of its crimes. For a long time the Foreign and Commonwealth Office denied the existence of files pertaining to the abuse of tens of thousands of detainees. "It is an enduring feature of our democracy," the FCO now claims, "that we are willing to learn from our history."

But what kind of history? Consider how Niall Ferguson, the Conservative-led government's favourite historian, deals with the Kenyan "emergency" in his book Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World: by suppressing it entirely in favour of a Kenyan idyll of "our bungalow, our maid, our smattering of Swahili – and our sense of unshakeable security."

The British had slaughtered the Kikuyu a few years before. But for Ferguson "it was a magical time, which indelibly impressed on my consciousness the sight of the hunting cheetah, the sound of Kikuyu women singing, the smell of the first rains and the taste of ripe mango".

Contrast this with the story of Albert Camus, who was ostracised by his intellectual peers when a sentimental attachment to the Algeria of his childhood turned him into a reluctant defender of French imperialism. Humiliated at Dien Bien Phu, and trapped in a vicious counter-insurgency in Algeria, the French couldn't really set themselves up as a beacon of tolerance and decency. Other French thinkers, from Roland Barthes to Michel Foucault, were already working to uncover the self-deceptions of their imperial culture, and recording the provincialism disguised by their mission civilisatrice. Visiting Japan in the late 1960s, Barthes warned that "someday we must write the history of our own obscurity – manifest the density of our narcissism".

Perhaps narcissism and despair about their creeping obscurity, or just plain madness explains why in the early 21st century many Britons, long after losing their empire, thought they had found a new role: as boosters to their rich English-speaking cousins across the Atlantic.

Astonishingly, British imperialism, seen for decades by western scholars and anticolonial leaders alike as a racist, illegitimate and often predatory despotism, came to be repackaged in our own time as a benediction that, in Ferguson's words, "undeniably pioneered free trade, free capital movements and, with the abolition of slavery, free labour". Andrew Roberts, a leading mid-Atlanticist, also made the British empire seem like an American neocon wet dream in its alleged boosting of "free trade, free mobility of capital … low domestic taxation and spending and 'gentlemanly' capitalism".

Never mind that free trade, introduced to Asia through gunboats, destroyed nascent industry in conquered countries, that "free" capital mostly went to the white settler states of Australia and Canada, that indentured rather than "free" labour replaced slavery, and that laissez faire capitalism, which condemned millions to early death in famines, was anything but gentlemanly.

These fairytales about how Britain made the modern world weren't just aired at some furtive far-right conclave or hedge funders' retreat. The BBC and the broadsheets took the lead in making them seem intellectually respectable to a wide audience. Mainstream politicians as well as broadcasters deferred to their belligerent illogic. Looking for a more authoritative audience, the revanchists then crossed the Atlantic to provide intellectual armature to Americans trying to remake the modern world through military force.

Of course, like Camus – who never gave any speaking parts to Arabs when he deigned to include them in his novels set in Algeria – the new bards of empire almost entirely suppressed Asian and African voices. The omission didn't matter in a world where some crass psychologising about gay men triggers an instant mea culpa (as it did with Ferguson's Keynes apology), but no regret, let alone repentance, is deemed necessary for a counterfeit imperial history and minatory visions of hectically breeding Muslims – both enlisted in large-scale violence against voiceless peoples.

Such retro-style megalomania, however, cannot be sustained in a world where, for better and for worse, cultural as well as economic power is leaking away from the old Anglo-American establishment. An enlarged global public society, with its many dissenting and corrective voices, can quickly call the bluff of lavishly credentialled and smug intellectual elites. Furthermore, neo-imperialist assaults on Iraq and Afghanistan have served to highlight the actual legacy of British imperialism: tribal, ethnic and religious conflicts that stifled new nation states at birth, or doomed them to endless civil war punctuated by ruthless despotisms.

Defeat and humiliation have been compounded by the revelation that those charged with bringing civilisation from the west to the rest have indulged – yet again – in indiscriminate murder and torture. But then as

Randolph Bourne pointed out a century ago: "It is only liberal naivete that is shocked at arbitrary coercion and suppression. Willing war means willing all the evils that are organically bound up with it."

This is as true for the Japanese, the self-appointed sentinel of Asia and then its main despoiler during the second world war, as it is for the British. Certainly, imperial power is never peaceably acquired or maintained. The grandson of a Kenyan once tortured by the British knows this too well as: having failed to close down Guantánamo, he resorts to random executions through drone strikes.

The victims of such everyday violence have always seen through its humanitarian disguises. They have long known western nations, as James Baldwin wrote, to be "caught in a lie, the lie of their pretended humanism". They know, too, how the colonialist habits of ideological deceit trickle down and turn into the mendacities of postcolonial regimes, such as in Zimbabwe and Syria, or of terrorists who kill and maim in the cause of anti-imperialism.

Fantasies of moral superiority and exceptionalism are not only a sign of intellectual vapidity and moral torpor, they are politically, economically and diplomatically damaging. Japan's insistence on glossing over its brutal invasions and occupations in the first half of the 20th century has isolated it within Asia and kept toxic nationalisms on the boil all around it. In contrast, Germany's clear-eyed reckoning and decisive break with its history of violence has helped it become Europe's pre-eminent country.

Britain's extended imperial hangover can only elicit cold indifference from the US, which is undergoing epochal demographic shifts, isolation within Europe, and derision from its former Asian and African subjects. The revelations of atrocities in Kenya are just the tip of an emerging global history of violence, dispossession and resistance. They provide a new opportunity for the British ruling class and intelligentsia to break with threadbare imperial myths – to come to the end of themselves as they were, and remake Britain for the modern world.