'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label compensation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label compensation. Show all posts

Thursday, 19 January 2023

Saturday, 19 December 2020

Monday, 10 June 2013

This battle over how Britain's military and colonial history is taught is also a battle for Britain's future

by Yasmin Alibhai Brown in The Independent

The Government has just agreed to pay £20m to over 5,000 Kenyans tortured under British rule during the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s. William Hague, in a commendably sober speech, accepted that the victims had suffered pain and grief. Out rode military expert Sir Max Hastings, apoplectic, a very furious Mad Max. Gabriel Gatehouse, the BBC Radio 4 reporter who interviewed survivors, “should die of shame”, roared the Knight of the Realm. Kenyan Human Rights organisations and native oral testimonies could not be trusted; the real baddies were the Mau Mau; no other nation guilty of crimes ever pays compensation and expresses endless guilt and finally there “comes a moment when you have to draw a line under it”. Actually Sir, the Japanese did compensate our PoWs in 2000, and Germany has never stopped paying for what it did to Jewish people.

The UK chooses to relive historical episodes of glory, and there were indeed many of those. But we also glorify those periods which were anything but glorious, and wilfully edit out the dark, unholy, inconvenient parts of the national story. Several other ex-imperial nations do the same. In Turkey, it is illegal to talk publicly about the Armenian Genocide by the Ottomans. France has neatly erased its vicious rule in Arab lands; the US only remembers its own dead in the Vietnam War, not the devastation of that country and its people. Britain proudly remembers the Abolitionists but gets very tetchy when asked to remember slavery, without which there would have been no need for Abolition. The Raj is still seen as a civilizing mission, not as a project of greed and subjugation. Not all the empire builders were personally evil, but occupation and unwanted rule is always morally objectionable. Tony Blair was probably taught too much of the aggrandising stuff and not enough about the ethics of Empire. The Scots, in any case, in spite of being totally involved, have offloaded all culpability for slavery and Empire on to the English. Their post-devolution history has been polished up well. But it is a flattering, falsifying mirror.

Indian history, as retold by William Dalrymple and Pankaj Mishra, among others, is very different from the “patriotic” accounts Britons have been fed for over a century. The 1857 Indian Uprising, for example, was a violent rebellion during which British men, women and children were murdered – so too was the Mau Mau insurrection – but the reprisals were much crueller and against many more people, many innocent. Our War on Terror is just as asymmetrical.

Today we get to hear plans to mark the centenary of the start of the First World War. The Coalition Government wants to spin this terrible conflict into another victory fest in 2014. Brits addicted to war memorialising will cheer. Michael Gove will have our children remembering only the “greatness” of the Great War and David Cameron will pledge millions of pounds for events which will stress the national spirit and be as affirming as “the diamond Jubilee celebrations”. I bet Max Hastings won’t ask for a line to be drawn under that bit of the nation’s past.

A group of writers, actors and politicians, including Jude Law, Tony Benn, Harriet Walter, Tim Pigott-Smith, Ralph Steadman, Simon Callow, Michael Morpurgo and Carol Ann Duffy has expressed concern that such a “military disaster and human catastrophe” is to be turned into another big party: “We believe it is important to remember that this was a war that was driven by big powers’ competition for influence around the globe and caused a degree of suffering all too clear in the statistical record of 16 million people dead and 20 million wounded”. After 1916, soldiers were conscripted from the poorest of families. The officer classes saw them as fodder. Traumatised soldiers, as we know, were shot. In school back in Uganda, I learnt the only words of Latin I know, Wilfred Owen’s Dulce et Decorum Est. His poems got into my heart and there they stay.

Let’s not expect the Establishment keepers of our past to dwell unduly on those facts and figures; or to acknowledge the land grabs in Africa in the latter part of the 19th-century which led to that gruesome war; or to remember how it played out on that continent. With the focus forever on the fields of Flanders, forgotten are those other theatres of that war, in East Africa, Iraq, Egypt and elsewhere.

In Tanganyika, where my mother was born, the Germans played dirty and the British fought back using over 130,000 African and Indian soldiers, thousands of them who died horrible deaths. Her father told her stories of, yes, torture by whites on both sides, trees bent over with strung up bodies, some pregnant women, and fear you could smell on people and in homes. Edward Paice’s book Tip and Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great Warin Africa, finally broke the long conspiracy of partiality.

The historical truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth matters. It is hard to get at and forever contested, but the aspiration still matters more than almost anything else in a nation’s self-portrait. With incomplete verities and doctored narratives, younger generations are bound to repeat the mistakes and vanities of the past. There will be a third global war because not enough lessons were learnt about earlier, major modern conflicts. And then our world will end.

Thursday, 9 May 2013

The sun is at last setting on Britain's imperial myth

The atrocities in Kenya are the tip of a history of violence that reveals the repackaging of empire for the fantasy it is

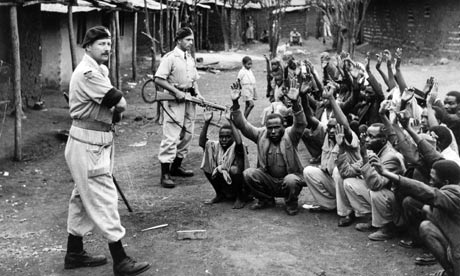

'Consider how Niall Ferguson deals with the Kenyan emergency: by suppressing it entirely in favour of a Kenyan idyll of 'our bungalow, our maid, our smattering of Swahili – and our sense of unshakeable security' in his book Empire.' Photograph: Popperfoto/Popperfoto/Getty Images

Scuttling away from India in 1947, after plunging the jewel in the crown into a catastrophic partition, "the British", the novelist Paul Scott famously wrote, "came to the end of themselves as they were". The legacy of British rule, and the manner of their departures – civil wars and impoverished nation states locked expensively into antagonism, whether in the Middle East, Africa or the Malay Peninsula – was clearer by the time Scott completed his Raj Quartet in the early 1970s. No more, he believed, could the British allow themselves any soothing illusions about the basis and consequences of their power.

Scott had clearly not anticipated the collective need to forget crimes and disasters. The Guardian reports that the British government is paying compensation to the nearly 10,000 Kenyans detained and tortured during the Mau Mau insurgency in the 1950s. In what has been described by the historian Caroline Elkins as Britain's own "Gulag", Africans resisting white settlers were roasted alive in addition to being hanged to death. Barack Obama's own grandfather had pins pushed into his fingers and his testicles squeezed between metal rods.

The British colonial government destroyed the evidence of its crimes. For a long time the Foreign and Commonwealth Office denied the existence of files pertaining to the abuse of tens of thousands of detainees. "It is an enduring feature of our democracy," the FCO now claims, "that we are willing to learn from our history."

But what kind of history? Consider how Niall Ferguson, the Conservative-led government's favourite historian, deals with the Kenyan "emergency" in his book Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World: by suppressing it entirely in favour of a Kenyan idyll of "our bungalow, our maid, our smattering of Swahili – and our sense of unshakeable security."

The British had slaughtered the Kikuyu a few years before. But for Ferguson "it was a magical time, which indelibly impressed on my consciousness the sight of the hunting cheetah, the sound of Kikuyu women singing, the smell of the first rains and the taste of ripe mango".

Clearly awed by this vision of the British empire, the current minister for education asked Ferguson to advise on the history syllabus. Schoolchildren may soon be informed that the British empire, as Dominic Sandbrook wrote in the Daily Mail, "stands out as a beacon of tolerance, decency and the rule of law".

Contrast this with the story of Albert Camus, who was ostracised by his intellectual peers when a sentimental attachment to the Algeria of his childhood turned him into a reluctant defender of French imperialism. Humiliated at Dien Bien Phu, and trapped in a vicious counter-insurgency in Algeria, the French couldn't really set themselves up as a beacon of tolerance and decency. Other French thinkers, from Roland Barthes to Michel Foucault, were already working to uncover the self-deceptions of their imperial culture, and recording the provincialism disguised by their mission civilisatrice. Visiting Japan in the late 1960s, Barthes warned that "someday we must write the history of our own obscurity – manifest the density of our narcissism".

Perhaps narcissism and despair about their creeping obscurity, or just plain madness explains why in the early 21st century many Britons, long after losing their empire, thought they had found a new role: as boosters to their rich English-speaking cousins across the Atlantic.

Astonishingly, British imperialism, seen for decades by western scholars and anticolonial leaders alike as a racist, illegitimate and often predatory despotism, came to be repackaged in our own time as a benediction that, in Ferguson's words, "undeniably pioneered free trade, free capital movements and, with the abolition of slavery, free labour". Andrew Roberts, a leading mid-Atlanticist, also made the British empire seem like an American neocon wet dream in its alleged boosting of "free trade, free mobility of capital … low domestic taxation and spending and 'gentlemanly' capitalism".

Never mind that free trade, introduced to Asia through gunboats, destroyed nascent industry in conquered countries, that "free" capital mostly went to the white settler states of Australia and Canada, that indentured rather than "free" labour replaced slavery, and that laissez faire capitalism, which condemned millions to early death in famines, was anything but gentlemanly.

These fairytales about how Britain made the modern world weren't just aired at some furtive far-right conclave or hedge funders' retreat. The BBC and the broadsheets took the lead in making them seem intellectually respectable to a wide audience. Mainstream politicians as well as broadcasters deferred to their belligerent illogic. Looking for a more authoritative audience, the revanchists then crossed the Atlantic to provide intellectual armature to Americans trying to remake the modern world through military force.

Of course, like Camus – who never gave any speaking parts to Arabs when he deigned to include them in his novels set in Algeria – the new bards of empire almost entirely suppressed Asian and African voices. The omission didn't matter in a world where some crass psychologising about gay men triggers an instant mea culpa (as it did with Ferguson's Keynes apology), but no regret, let alone repentance, is deemed necessary for a counterfeit imperial history and minatory visions of hectically breeding Muslims – both enlisted in large-scale violence against voiceless peoples.

Such retro-style megalomania, however, cannot be sustained in a world where, for better and for worse, cultural as well as economic power is leaking away from the old Anglo-American establishment. An enlarged global public society, with its many dissenting and corrective voices, can quickly call the bluff of lavishly credentialled and smug intellectual elites. Furthermore, neo-imperialist assaults on Iraq and Afghanistan have served to highlight the actual legacy of British imperialism: tribal, ethnic and religious conflicts that stifled new nation states at birth, or doomed them to endless civil war punctuated by ruthless despotisms.

Defeat and humiliation have been compounded by the revelation that those charged with bringing civilisation from the west to the rest have indulged – yet again – in indiscriminate murder and torture. But then as Randolph Bourne pointed out a century ago: "It is only liberal naivete that is shocked at arbitrary coercion and suppression. Willing war means willing all the evils that are organically bound up with it."

This is as true for the Japanese, the self-appointed sentinel of Asia and then its main despoiler during the second world war, as it is for the British. Certainly, imperial power is never peaceably acquired or maintained. The grandson of a Kenyan once tortured by the British knows this too well as: having failed to close down Guantánamo, he resorts to random executions through drone strikes.

The victims of such everyday violence have always seen through its humanitarian disguises. They have long known western nations, as James Baldwin wrote, to be "caught in a lie, the lie of their pretended humanism". They know, too, how the colonialist habits of ideological deceit trickle down and turn into the mendacities of postcolonial regimes, such as in Zimbabwe and Syria, or of terrorists who kill and maim in the cause of anti-imperialism.

Fantasies of moral superiority and exceptionalism are not only a sign of intellectual vapidity and moral torpor, they are politically, economically and diplomatically damaging. Japan's insistence on glossing over its brutal invasions and occupations in the first half of the 20th century has isolated it within Asia and kept toxic nationalisms on the boil all around it. In contrast, Germany's clear-eyed reckoning and decisive break with its history of violence has helped it become Europe's pre-eminent country.

Britain's extended imperial hangover can only elicit cold indifference from the US, which is undergoing epochal demographic shifts, isolation within Europe, and derision from its former Asian and African subjects. The revelations of atrocities in Kenya are just the tip of an emerging global history of violence, dispossession and resistance. They provide a new opportunity for the British ruling class and intelligentsia to break with threadbare imperial myths – to come to the end of themselves as they were, and remake Britain for the modern world.

Thursday, 29 November 2012

Parkinson's sufferer wins six figure payout from GlaxoSmithKline over drug that turned him into a 'gay sex and gambling addict'

A French appeals court has upheld a ruling ordering GlaxoSmithKline to pay €197,000 (£159,000) to a man who claimed a drug given to him to treat Parkinson's turned him into a 'gay sex addict'.

Didier Jambart, 52, was prescribed the drug Requip in 2003 to treat his illness.

Within two years of beginning to take the drug the married father-of-two says he developed an uncontrollable passion for gay sex and gambling - at one point even selling his children's toys to fund his addiction.

He was awarded £160,000 in damages after a court in Rennes, France, upheld his claims.

The ruling, which is considered ground-breaking, was made yesterday by the appeal court, which awarded damages to Mr Jambart.

Following the decision Mr Jambart appeared outside the court with his wife Christine beside him.

Jambart broke down in tears as judges upheld his claim that his life had become 'hell' after he started taking Requip, a drug made by GSK.

Mr Jambart began taking the drug for Parkinson's in 2003, he had formerly worked as a well-respected bank manager and local councillor, and is a father of two.

In total Mr Jambert said he gambled away 82,000 euros, mostly through internet betting on horse races. He also said he engaged in frantic searches for gay sex.

He started exhibiting himself on websites and arranging encounters, one of which he claimed resulted in him being raped.

He said his family had not understood what was going on at first.

Mr Jambert said he realised the drug was responsible when he stumbled across a website that made a connection between the drug and addictions in 2005. When he stopped the drug he claims his behaviour returned to normal.

"It's a great day," he said. "It's been a seven-year battle with our limited means for recognition of the fact that GSK lied to us and shattered our lives."

He added: 'I am happy that justice has been done. I am happy for my wife and my children. I am at last going to be able to sleep at night and profit from life. '

He added that the money awarded would, 'never replace the years of pain.'

The court heard that Requip's side-effects had been made public in 2006, but had reportedly been known for years.

Mr Jambert said that GSK patients should have been informed earlier.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)