Kenya’s eruption of protests, riots and government repression is the result of decades of failed western financial prescriptions writes Fadhel Kaboub in The Guardian

It took several days of peaceful popular uprisings, violent confrontations with the police and the army, the illegal arrests and detention of protesters, the tragic death of several protesters at the hands of state security forces, and the burning of its parliament building for the Kenyan government to finally withdraw a finance bill that would have imposed the most extreme form of austerity in Kenya’s history.

Protesters held signs directly blaming the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for last year’s increases in VAT taxes, fuel and food prices, and for the new tax hikes proposed in the now defunct 2024 finance bill. This was in fact what the IMF has imposed on Kenya under the 2021 loan agreement for a 38-month program unlocking $3.9bn subject to periodic reviews designed to verify that Nairobi is actually doing what the IMF wants: to increase taxes, reduce subsidies and cut government waste (a code word for privatisation of state-owned enterprises).

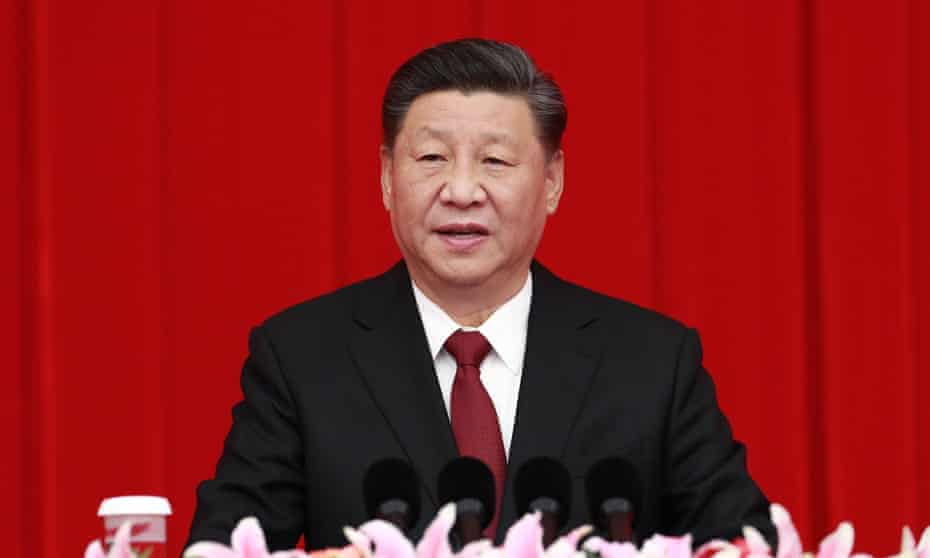

Protesters also know that IMF-imposed austerity is backed by the United States, which, as the main shareholder in the organization, essentially holds a veto power on its programs. And every Kenyan knows that President William Ruto has become the new darling of the US and the G7 for agreeing to send Kenyan troops to Haiti, for not being too radical in his demands for reforming international financial architecture, for being conservative in representing Africa’s position in climate negotiations, and for accepting financing terms that favor the interests of foreign investors.

Kenya can have democracy or neocolonial extraction, but not both – because democracy means addressing the demands of the Kenyan people for jobs, healthcare, education, housing, transportation and basic social protections under a fair and equitable fiscal regime, while colonial extraction means the destruction of economic and monetary sovereignty, austerity for the poor, extravagant lifestyles for the elites, corruption, injustice and socioeconomic exclusion under a fiscal regime that accelerates the engines of economic entrapment.

One cannot democratize a system that hasn’t been structurally and economically decolonized yet. Despite Kenya’s democratic institutions, transparent elections, independent judiciary, freedom of speech and vibrant civil society spaces, its elected governments systematically undermine the social and economic demands of Kenya’s population – less because those governments wish to ignore the mandate given to them by the electorate, but because they face financial pressures from abroad that force them to prioritize external debt service and the financial needs of creditors and foreign investors.

In 2019, Kenya used 19% of its export revenues to service external debt; today that number has jumped up to nearly 50%. When a country uses half of its export revenues to pay interest on its external debt instead of investing in the basic pillars of development and prosperity, it is not surprising to see the kind of revolt that we have seen in Nairobi against the 2024 finance bill.

This makes Kenya a classic case of an economy steered from abroad, by colonial design rather than by accident.

The fact that Kenya is in a debt trap after decades of following IMF policy prescriptions means that either the IMF is incompetent or it is engaging in intentional economic entrapment. I believe it’s the latter. It is time to end the entrapment and to decolonize the Kenyan economy.

Decolonizing the Kenyan economy means escaping the colonial roles that were imposed on Kenya to serve as 1) the source of cheap raw materials, 2) the consumer of industrial output and technologies from the global north and 3) the recipient of obsolete technologies and outsourced assembly line manufacturing that is no longer needed in the industrialized countries, thus locking Kenya permanently at the bottom of the global value chain.

In fact, Kenya’s external debt crisis is the symptom of neocolonial structural traps that include food, energy and manufacturing deficits. First, Kenya’s largest agricultural exports are tea, cut flowers and coffee (colonial cash crops), while its imports include core crops like wheat, rice and corn. Second, Kenya’s largest import items are refined petroleum products.

And third, the kind of manufacturing that Kenya was allowed to have requires importing the machines, the fuel to power its factories, the intermediate components to be assembled by low-cost labor and even the packaging. As a result, Kenya’s exports have low value-added content, while its imports have high value-added content, which is why Kenya is locked at the bottom of the global value chain like the rest of the global south.

These structural trade deficits constantly weaken the Kenyan shilling relative to the US dollar, and with a weaker currency anything Kenya imports (food, fuel, medicine) becomes more expensive. Therefore, Kenya imports inflation with the most sensitive consumer items, which forces the Kenyan government to protect the most vulnerable people with defensive Band-Aid policies like food and fuel subsidies and exchange-rate management policies that require more external borrowing to stabilize the value of the shilling, thus accelerating the external debt crisis.

Decolonizing the Kenyan economy requires strategic investments in food sovereignty, agroecology, renewable energy sovereignty, and regional and Pan-African industrial policies. These are precisely the agenda items that are never discussed with G7, EU and US counterparts when they roll out the red carpet for President Ruto.

Unfortunately, despite being aware of these structural traps, Ruto has opted to listen to policy advice from global north institutions rather than Kenyan and Pan-African independent experts, thinktanks and civil society organizations.

Instead of limiting his demands for reforming the global financial architecture to lower borrowing rates, Ruto should be demanding the transfer of life-saving technologies to decolonize African economies, debt cancellation (not restructuring) and grants (not loans) for climate action. That would be the foundation for a finance bill that will meet the democratic needs and aspirations of the Kenyan people.