'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Wednesday, 27 December 2023

Thursday, 27 July 2023

Friday, 19 May 2023

Friday, 17 February 2023

Unreliable Macroeconomic Forecasts and Corporate Business Plans

Anne-Sylvaine Chassany in The FT

Top Ikea executive Jesper Brodin says he is not usually one to indulge in nostalgia. But at a pre-Christmas gathering for senior managers that used to work at the Swedish furniture group, he could not help but join with the chorus of those who said they missed the old times — when the world seemed relatively stable, trends were predictable and this could be translated into a more or less credible multiyear business plan.

Friday, 3 February 2023

How to fix the British economy

Tim Harford in The FT

I recently argued that the UK’s economic performance has been disastrous for 15 years. The consequences are plain to see: people are struggling to make ends meet; taxes are high, yet public services are overloaded; fights over a shrinking economic pie are leading to widespread strikes. All this is taking place at a time of low unemployment, so we cannot simply wait for the business cycle to rescue us.

If we could somehow improve the UK’s productivity growth rate, all of these problems would become easier to solve, and we could return to the business-as-usual of each generation being able to earn more than their parents, while working less and enjoying better conditions.

But how?

Start with a diagnosis of what ails the UK economy. The view from the right is that the UK is suffering from excessive taxes and red tape. This seems implausible. Taxes are certainly high by historical standards, but they have only recently spiked, yet productivity and growth have been disappointing since 2007. And there are plenty of richer economies with higher taxes.

Nor is red tape to blame. According to the OECD, UK product market regulations are among the most competitive.

The critique from the left focuses on inequality, but this is an old and mostly separate problem. Like any mixed-market economy, the UK is an unequal society, but income inequality in the UK is slightly lower now than at the time of the financial crisis and has barely changed over the past 20 years. A more relevant manifestation of inequality is the one between global titan London and regional capitals such as Manchester, which remain far behind in terms of value added per worker.

Then there’s the centrist critique: blame Brexit. Now I am as prone to highlight the idiocies of Brexit as anyone, but unless Nigel Farage has discovered a time machine, a referendum decision in 2016 cannot be blamed for poor productivity performance starting around 2007. Brexit has solved nothing, and by creating barriers to trade with our most important trading partners, along with endless uncertainty, it is demonstrably making the situation worse. But the UK’s economic problems became apparent long before the referendum.

The slightly tedious truth is that taxes, regulation, inequality and Brexit can all take a little bit of blame, alongside a gaggle of other culprits. (Professor Diane Coyle of Cambridge university has memorably likened the case to an Agatha Christie mystery: everybody did it.)

To pick a few of these culprits at random, the quality of management in British companies is the worst in the G7, according to research by economists Nick Bloom, Raffaella Sadun and John Van Reenen. The country skimps on investment; total investment was the lowest in the G7 over the four decades preceding the pandemic. As a result, energy and transport infrastructure is run down. The Transpennine railway project is a case in point: a decade of dithering, nearly £200mn wasted and a project which was supposed to have opened in 2019 still exists largely in the imagination. Why? Politicians were more interested in announcing plans than in planning.

Low investment from the private sector is now a more acute problem than in the public sector. Is this managerial incompetence? A lack of business finance from a too-concentrated retail banking sector? A logical response to the chronic political uncertainties of the past 15 years?

Then there is the education system. It works well at the top, where British universities are still magnets for talent, but schooling is patchy and many young people, especially from deprived backgrounds, are poorly served.

Kate Bingham, who chaired the UK’s Covid vaccine development programme, recently wrote in the FT that “short-term pressures are crowding out long-term solutions”. She was pleading the case for the UK’s life-science industry, but she could easily have been describing the British condition. Short-termism is now ubiquitous. For such a venerable polity, we have developed a shocking inability to think beyond the next few weeks.

The few examples of policy excellence in the past 15 years have been times where our politicians or civil servants have risen to the challenge in a moment of crisis: I would suggest the Brown-Darling plan to prevent the banking system collapsing in 2008, the Johnson administration’s vaccine task force in 2020 and Johnson’s full-throated early support for Ukraine in 2022. Even when the UK government excels, it is not thanks to patient long-term reform and investment.

It is easy to produce a list of sensible ways forward: modernise taxes to raise more revenue with fewer distortions; improve relations with the EU and streamline UK-EU trade, especially in services; liberalise planning rules to create jobs and cheaper, better homes. But all policy wonks and most politicians know this; nothing ever happens.

It is sobering to re-read the LSE’s Growth Commission report of 2017. Many of its proposals were not policy proposals, but institutional reforms to keep the politicians away from policy proposals: Bank of England independence, but for everything. Contemplate the recent accomplishments of Whitehall and Westminster, and you see where the Growth Commission was coming from.

While researching this column, I found a video of the commission’s co-chair, John Van Reenen, in which he described “what we need to do over the next 50 years”. It seemed an impossibly daunting timescale. Then I realised the video had been posted almost exactly 10 years ago. We could have started then. We didn’t, and we’ve gone backwards. We could at least start now.

Wednesday, 8 December 2021

Wednesday, 27 October 2021

Don’t blame Nehru’s Socialism for Air India fate. Read the 1944 Bombay Plan first

Air India’s privatisation is finally underway, albeit, belatedly. Consequently, this has led to conversations around the planned economy, and in turn blamed the Socialist economy for India’s woes. These debates presume that India was forced into planning; this assumption undermines the country’s economic history, and disregards the role that Indian businesses played in shaping economic policy leading up to Independence.

In 1944, during the height of the Bengal famine, and with the seeming inevitability of Independence, J.R.D. Tata and seven other industrialists and executives — G.D. Birla, Purushottam Das Thakurdas, Ardeshir Shroff, Kasturbhai Lalbhai, Ardeshir Dalal, John Matthai, and Lal Shri Ram — came together to write a manifesto on the future of the Indian economy post-Independence. This was known as the Bombay Plan, or more formally called A Plan of Economic Development for India. The authors of the plan helped set up the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), supported the Indian National Congress (INC) during the Freedom struggle and even sat on the viceroy’s executive council during WWII.

View on economy

The Bombay Plan aimed to express the authors’ views on the post-Independence economy. It had the following components: a transition from agricultural domination to industrialisation; the allocation of resources through centralised planning, and the division of industries into ‘basic industries’, dominated by the State, and ‘consumer industries’, left to the private sector. From its outset, the plan acknowledged the primacy of the State in organising the economy and providing basic necessities to citizens. Historians such as Medha Kudaisya call the plan “a revolutionary idea” in State planning since it adopted a middle way for the private sector to coexist in a planned economy. On the other hand, Vivek Chibber in Locked in Place, argues that the plan was a way for businesses to entrench their own vested interests. (Vivek Chibber, Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India (Princeton, N.J. ; Princeton University Press, 2006), 86.)

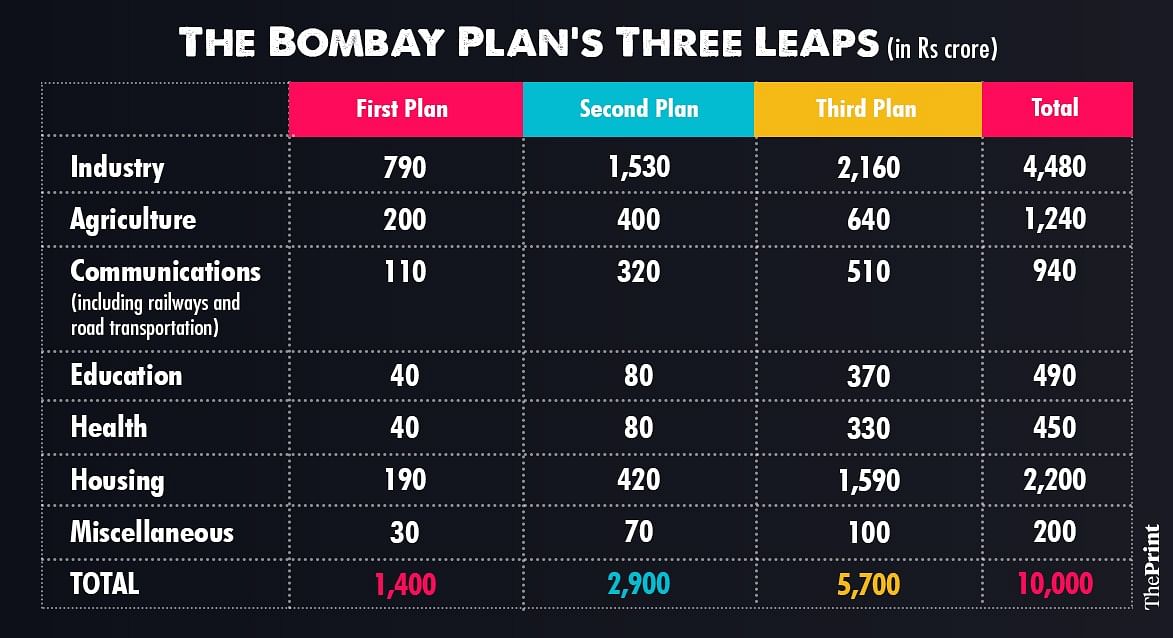

The principle objective of the plan was “to bring about a doubling of the present per capita income within a period of fifteen years from the time the plan comes into operation,” and increase production of power and capital goods. It then went on to define a reasonable living standard, cost of housing, clothing and food to individuals, housing requirements, and the provision of essential infrastructure like sewage treatment, water and electricity. It planned to achieve these aims in three ‘leaps’ spread over five years, analogous to the Five-Year Plans. The table below reflects these priorities.

Graphic by Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrint

Graphic by Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrintThe planners argued for a ‘mixed-economy’ model, where the government would take control of ‘basic industries,’ and the private sector would take charge of ‘consumer industries’. Basic industries included transportation, chemicals, power generation, and steel production. More significantly, they argued that nationalisation of basic industries could reduce income disparities and that the government had to prioritise basic industries over consumption to reduce poverty. The planners conclude this section by saying, “for the success of our economic plan that the basic industries, on which ultimately the whole economic development of the country depends, should be developed as rapidly as possible,” emphasising that the government needed to take a leading role in the economy to ensure their provision. This shows that the the business community conceded the centrality of the State in building India’s economy.

The plan was well received, with endorsements from FICCI, RBI Governor C.D. Deshmukh, and the viceroy, who in response to the plan document had established a Department of Planning and Development in 1944 (Tryst with Prosperity). Newspaper editorials in India and abroad supported the plan. The Glasgow Herald commended the planners for thinking about issues such as “public health, population control and education” that “Indian political leaders [could not] be induced to think about, however urgent.” The New York Times reported that “the main political factions in India do not seem to be coming forward with any such practical approaches,” reiterating the view that India’s political elite had not considered policy solutions to India’s problems. However, the plan document was criticised as well for being inaccurate and a vehicle for the elite to entrench their interests over the interests of the poor by K.T. Shah, general secretary of the 1937-38 NPC and Gulzarilal Nanda, future Planning Minister (1951-63)and other economists. Its calculations relied on statistics from 1932, making its assumptions highly outdated and it underestimated the costs of implementing its aims.

Influence on economic planning

The document was significant since it reframed debates on State planning — from arguing if the State should dominate the economy, to analysing the extent to which the State should be involved in the economy. Its influence on Indian economic planning is clearly seen in the immediate aftermath of WWII, and in the First and Second Five-Year Plans that prioritised agricultural development and industrial growth, respectively. It also paved the way for India to adopt a third way in structuring its political economy by providing an opportunity to the country to combine aspects of Western capitalism, Soviet planning, and Western Socialism, allowing India to chart its own independent course. To many, the plan was a way for businesses to signal to the INC leadership that it was willing to accept the supremacy of the State in the economy, while acknowledging the role of the private sector in supporting consumption activity.

Insisting that Nehruvian Socialism was the cause for India’s economic ills without acknowledging the political and economic contexts of post-Independence India reflects an incomplete understanding of India’s formative years after independence. The Bombay Plan is an essential document to understanding the events that led to the creation of India’s planned economy, and reiterates the view that planning was not imposed on the country, but was widely debated across the private and public sphere in the years leading up to Independence.

Thursday, 14 May 2020

The coronavirus slayer! How Kerala's rock star health minister helped save it from Covid-19

On 20 January, KK Shailaja phoned one of her medically trained deputies. She had read online about a dangerous new virus spreading in China. “Will it come to us?” she asked. “Definitely, Madam,” he replied. And so the health minister of the Indian state of Kerala began her preparations.

Four months later, Kerala has reported only 524 cases of Covid-19, four deaths and – according to Shailaja – no community transmission. The state has a population of about 35 million and a GDP per capita of only £2,200. By contrast, the UK (double the population, GDP per capita of £40,400) has reported more than 40,000 deaths, while the US (10 times the population, GDP per capita of £51,000) has reported more than 82,000 deaths; both countries have rampant community transmission.

As such, Shailaja Teacher, as the 63-year-old minister is affectionately known, has attracted some new nicknames in recent weeks – Coronavirus Slayer and Rockstar Health Minister among them. The names sit oddly with the merry, bespectacled former secondary school science teacher, but they reflect the widespread admiration she has drawn for demonstrating that effective disease containment is possible not only in a democracy, but in a poor one.

How has this been achieved? Three days after reading about the new virus in China, and before Kerala had its first case of Covid-19, Shailaja held the first meeting of her rapid response team. The next day, 24 January, the team set up a control room and instructed the medical officers in Kerala’s 14 districts to do the same at their level. By the time the first case arrived, on 27 January, via a plane from Wuhan, the state had already adopted the World Health Organization’s protocol of test, trace, isolate and support.

As the passengers filed off the Chinese flight, they had their temperatures checked. Three who were found to be running a fever were isolated in a nearby hospital. The remaining passengers were placed in home quarantine – sent there with information pamphlets about Covid-19 that had already been printed in the local language, Malayalam. The hospitalised patients tested positive for Covid-19, but the disease had been contained. “The first part was a victory,” says Shailaja. “But the virus continued to spread beyond China and soon it was everywhere.”

In late February, encountering one of Shailaja’s surveillance teams at the airport, a Malayali family returning from Venice was evasive about its travel history and went home without submitting to the now-standard controls. By the time medical personnel detected a case of Covid-19 and traced it back to them, their contacts were in the hundreds. Contact tracers tracked them all down, with the help of advertisements and social media, and they were placed in quarantine. Six developed Covid-19.

Another cluster had been contained, but by now large numbers of overseas workers were heading home to Kerala from infected Gulf states, some of them carrying the virus. On 23 March, all flights into the state’s four international airports were stopped. Two days later, India entered a nationwide lockdown.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Indian citizens arriving from the Gulf states are bussed to a quarantine centre. Photograph: Arunchandra Bose/AFP via Getty Images

At the height of the virus in Kerala, 170,000 people were quarantined and placed under strict surveillance by visiting health workers, with those who lacked an inside bathroom housed in improvised isolation units at the state government’s expense. That number has shrunk to 21,000. “We have also been accommodating and feeding 150,000 migrant workers from neighbouring states who were trapped here by the lockdown,” she says. “We fed them properly – three meals a day for six weeks.” Those workers are now being sent home on charter trains.

Shailaja was already a celebrity of sorts in India before Covid-19. Last year, a movie called Virus was released, inspired by her handling of an outbreak of an even deadlier viral disease, Nipah, in 2018. (She found the character who played her a little too worried-looking; in reality, she has said, she couldn’t afford to show fear.) She was praised not only for her proactive response, but also for visiting the village at the centre of the outbreak.

The villagers were terrified and ready to flee, because they did not understand how the disease was spreading. “I rushed there with my doctors, we organised a meeting in the panchayat [village council] office and I explained that there was no need to leave, because the virus could only spread through direct contact,” she says. “If you kept at least a metre from a coughing person, it couldn’t travel. When we explained that, they became calm – and stayed.”

Nipah prepared Shailaja for Covid-19, she says, because it taught her that a highly contagious disease for which there is no treatment or vaccine should be taken seriously. In a way, though, she had been preparing for both outbreaks all her life.

The Communist Party of India (Marxist), of which she is a member, has been prominent in Kerala’s governments since 1957, the year after her birth. (It was part of the Communist Party of India until 1964, when it broke away.) Born into a family of activists and freedom fighters – her grandmother campaigned against untouchability – she watched the so-called “Kerala model” be assembled from the ground up; when we speak, this is what she wants to talk about.

The foundations of the model are land reform – enacted via legislation that capped how much land a family could own and increased land ownership among tenant farmers – a decentralised public health system and investment in public education. Every village has a primary health centre and there are hospitals at each level of its administration, as well as 10 medical colleges.

This is true of other states, too, says MP Cariappa, a public health expert based in Pune, Maharashtra state, but nowhere else are people so invested in their primary health system. Kerala enjoys the highest life expectancy and the lowest infant mortality of any state in India; it is also the most literate state. “With widespread access to education, there is a definite understanding of health being important to the wellbeing of people,” says Cariappa.

Shailaja says: “I heard about those struggles – the agricultural movement and the freedom fight – from my grandma. She was a very good storyteller.” Although emergency measures such as the lockdown are the preserve of the national government, each Indian state sets its own health policy. If the Kerala model had not been in place, she insists, her government’s response to Covid-19 would not have been possible.

FacebookTwitterPinterest A walk-in test centre in Ernakulam, Kerala. Photograph: Reuters

That said, the state’s primary health centres had started to show signs of age. When Shailaja’s party came to power in 2016, it undertook a modernisation programme. One pre-pandemic innovation was to create clinics and a registry for respiratory disease – a big problem in India. “That meant we could spot conversion to Covid-19 and look out for community transmission,” Shailaja says. “It helped us very much.”

When the outbreak started, each district was asked to dedicate two hospitals to Covid-19, while each medical college set aside 500 beds. Separate entrances and exits were designated. Diagnostic tests were in short supply, especially after the disease reached wealthier western countries, so they were reserved for patients with symptoms and their close contacts, as well as for random sampling of asymptomatic people and those in the most exposed groups: health workers, police and volunteers.

Shailaja says a test in Kerala produces a result within 48 hours. “In the Gulf, as in the US and UK – all technologically fit countries – they are having to wait seven days,” she says. “What is happening there?” She doesn’t want to judge, she says, but she has been mystified by the large death tolls in those countries: “I think testing is very important – also quarantining and hospital surveillance – and people in those countries are not getting that.” She knows, because Malayalis living in those countries have phoned her to say so.

Places of worship were closed under the rules of lockdown, resulting in protests in some Indian states, but resistance has been noticeably absent in Kerala – in part, perhaps, because its chief minister, Pinarayi Vijayan, consulted with local faith leaders about the closures. Shailaja says Kerala’s high literacy level is another factor: “People understand why they must stay at home. You can explain it to them.”

The Indian government plans to lift the lockdown on 17 May (the date has been extended twice). After that, she predicts, there will be a huge influx of Malayalis to Kerala from the heavily infected Gulf region. “It will be a great challenge, but we are preparing for it,” she says. There are plans A, B and C, with plan C – the worst-case scenario – involving the requisitioning of hotels, hostels and conference centres to provide 165,000 beds. If they need more than 5,000 ventilators, they will struggle – although more are on order – but the real limiting factor will be manpower, especially when it comes to contact tracing. “We are training up schoolteachers,” Shailaja says.

Once the second wave has passed – if, indeed, there is a second wave – these teachers will return to schools. She hopes to do the same, eventually, because her ministerial term will finish with the state elections a year from now. Since she does not think the threat of Covid-19 will subside any time soon, what secret would she like to pass on to her successor? She laughs her infectious laugh, because the secret is no secret: “Proper planning.”

Wednesday, 20 June 2018

A BJP MP's Analysis of his government

Political discourse is at it’s lowest point in the country, at least in my lifetime. The partisanship bias is unbelievable and people continue to support their side no matter what the evidence, there is no remorse even when they’re proved to have been spreading fake news. This is something that everyone – the parties and the voters or supporters are to be blamed for.

BJP has done a great job at spreading some specific messages with incredibly effective propaganda, and these messages are the primary reason that I can’t support the party anymore. But before we get into any of that, I’d like everyone to understand that no party is totally bad, and no party is totally good. All governments have done some good and messed up on some fronts. This government is no different.

The Good:

1. Road construction is faster than it was earlier. There has been a change in methodology of counting road length, but even factoring that in it seems to be faster.

2. Electricity connection increased – all villages electrified and people getting electricity for more hours. (Congress did electrify over 500,000 villages and Modi finished the job by connecting the last 18,000 or so, you can weigh the achievement as you like. Similarly, the number of hours people get electricity has increased ever since independence, but it might be a larger increase during BJP).

3. Upper-level corruption is reduced (Also read Electoral Bonds below) – no huge cases at the ministerial level as of now (but the same was true of UPA, the alliance formed after the 2004 poll). Lower level seems to be about the same with increased amounts, no one seems to be able to control the thanedar, patwari (village policeman, headman) et al.

4. The Swachh Bharat Mission (clean-up campaign) is a success – more toilets built than before and Swachhta is something embedded in people’s minds now.

5. Ujjwala Yojana (LPG connection scheme) is a great initiative. How many people buy the second cylinder remains to be seen. The first one and a stove was free, but now people need to pay for it. The cost of cylinders has almost doubled since the government took over and now one costs more than 800 rupees.

6. Connectivity for the Northeast has undoubtedly increased. More trains, roads, flights and most importantly – the region is now discussed in the mainstream news channels.

7. Law and order is reportedly better than it was under regional parties.

Feel free to add achievements you can think of in the comments below, also achievements necessarily have caveats, failures are absolute!

The Bad:

It takes decades and centuries to build systems and nations, the biggest failure I see in BJP is that it has destroyed some great things on very flimsy grounds.

1. Electoral Bonds – these basically legalize corruption and allow corporates and foreign powers to just buy our political parties. The bonds are anonymous, so if a corporate says ‘I’ll give you an electoral bond of 1,000 crore [10 billion rupees] if you pass this specific policy’, there will be no prosecution. There just is no way to establish quid pro quo with an anonymous instrument. This also explains how corruption is reduced at the ministerial level – it isn’t per file or order, it is now like the US, at the policy level.

2. Planning Commission Reports – this used to be a major source for data. They audited government schemes and stated how things are going. With that gone, there just is no choice but to believe whatever data the government gives you (Comptroller and Auditor General audits come out after a long time!). NITI Aayog (the National Institute for Transforming India) doesn’t have this mandate and is basically a think tank and PR agency. Plan or non-plan distinction could be removed without removing this!

3. Misuse of CBI and ED (the Central Bureau of Investigation and the Enforcement Directorate) – it is being used for political purposes as far as I can see, but even if it isn’t the fear that these institutions will be unleashed on them if they speak up against anything Modi or Shah-related is real. This is enough to kill dissent, an integral component of democracy.

4. Failure to investigate Kalikho Pul’s suicide note, Judge Loya’s death, the Sohrabuddin murder, the defense of an MLA accused of rape who’s relative is accused of killing the girl’s father and a First Information Report (to police) wasn’t registered for over a year!

5. Demonetization – it failed, but worse is BJP’s inability to accept that it failed. All propaganda of it cutting terror funding, reducing cash, eliminating corruption is just absurd. It also killed off businesses.

6. GST Implementation – Implemented in a hurry and harmed business. Complicated structure, multiple rates on different items, complex filing… Hopefully, it’ll stabilize in time, but it did cause harm. Failure to acknowledge that from BJP is extremely arrogant.

7. The messed-up foreign policy with pure grandstanding – China has a port in Sri Lanka, huge interests in Bangladesh and Pakistan – we’re surrounded, the failure in the Maldives (Indian workers not getting visas anymore because of India’s foreign policy debacle) while Modi-ji goes out to foreign countries and keeps saying Indians had no respect in the world before 2014 and now they’re supremely respected. (This is nonsense. Indian respect in foreign countries was a direct result of our growing economy and IT sector; it hasn’t improved an ounce because of Modi. Might even have declined due to beef-based lynchings, threats to journalists, etc.)

8. Failure of schemes and failure to acknowledge and correct the course – Sansad Adarsh Gram Yojana (rural development), Make In India, Skill Development, Fasal Bima (crop insurance: look at reimbursements – the government is lining the pockets of insurance companies). Failure to acknowledge unemployment and farmers crisis, calling every real issue an opposition stunt.

9. The high prices of petrol and diesel – Modi-ji and all BJP ministers and supporters criticized Congress for it heavily and now all of them justify the high prices even though crude is cheaper than it was then! Just unacceptable.

10. Failure to engage with the most important basic issues – education and healthcare. There is just nothing on education, which is the nation’s biggest failure. The quality of government schools has deteriorated over the decades (ASER reports) and no action. They did nothing on healthcare for four years, then Ayushman Bharat (National Health Protection scheme) was announced. That scheme scares me more than nothing being done. Insurance schemes have a terrible track record and this is going the US route, which is a terrible destination for healthcare (watch ‘Sicko’ by Michael Moore)!

You can add some and subtract some based on personal understanding of the issue, but this is my assessment. The Electoral Bonds thing is huge and hopefully the Supreme Court will strike it down! Every government has some failures and some bad decisions though, the bigger issue I have is more on morals than anything else.

The Ugly:

The real negative of this government is how it has affected the national discourse with a well-considered strategy. This isn’t a failure, it’s the plan.

1. It has discredited the media, so now every criticism is brushed off as a journalist who didn’t get paid by BJP or is on the payrolls of Congress. I know several journalists for whom the allegation can’t be true, but more importantly, no one ever addresses the accusation or complaint – they just attack the person raising the issue and ignore the issue itself.

2. It has peddled a narrative that nothing happened in India in 70 years. This is patently false and the mentality is harmful to the nation. This government spent over Rs. 4,000 crore (40 billion rupees) of our taxpayers’ money on advertisements and now that will become the trend. Do small works and huge branding. He isn’t the first one to build roads – some of the best roads I’ve traveled on were pet projects of Mayawati and Akhilesh Yadav. India became an IT powerhouse from the 90s. It is easy to measure past performance and berate past leaders based on the circumstances of today, just one example of that:

“Why did Congress not build toilets in 70 years? They couldn’t even do something so basic. This argument sounds logical and I believed it too, until I started reading India’s history. When we gained independence in 1947 we were an extremely poor country, we didn’t have the resources for even basic infrastructure and no capital. To counteract this PM Nehru went down the socialist path and created the concept of Public Sector Undertakings. We had no capacity to build steel, so with the help of Russians the Heavy Engineering Corporation (HEC), Ranchi was set up that made machines to make steel in India – without this we would have no steel, and consequently no infrastructure. That was the agenda – basic industries and infra. We had frequent droughts (aakaal), every 2-3 years and a large number of people starved to death. The priority was to feed the people, toilets were a luxury no one cared for. The Green Revolution happened and the food shortages disappeared by the 1990s – now we have a surplus problem. The toilet situation is exactly like people asking 25 years from now why Modi couldn’t make all houses in India air-conditioned. That seems like a luxury today, toilets were also a luxury at some point of time. Maybe things could have happened sooner, maybe 10-15 years ago, but nothing happened in 70 years is a horrible lie to peddle.”

3. The spread and reliance on Fake News. There is some anti-BJP fake news too, but the pro-BJP and anti-opposition fake news outstrips that by miles in number and in reach. Some of it is supporters, but a lot of it comes from the party. It is often hateful and polarizing, which makes it even worse. The online news portals backed by this government are damaging society more than we know.

4. Hindu khatre mein hai – they’ve ingrained it into the minds of people that Hindus and Hinduism are in danger, and that Modi is the only option to save ourselves.r In reality Hindus have been living the same lives much before this government and nothing has changed except people’s mindset. Were we Hindus in danger in 2007? At least I didn’t hear about it everyday and I see no improvement in the condition of Hindus, just more fear mongering and hatred.

5. Speak against the government and you’re anti-national and more recently, anti-Hindu. Legitimate criticism of the government is shut up with this labeling. Prove your nationalism, sing Vande Mataram everywhere (even though BJP leaders don’t know the words themselves, they’ll force you to sing it!). I’m a proud nationalist and my nationalism won’t allow me to let anyone force me to showcase it! I will sing the national anthem and national song with pride when the occasion calls for it, or when I feel like it, but I won’t let anyone force me to sing it based on their whims!

6. Running news channels that are owned by BJP leaders who’s sole job is to debate Hindu-Muslim, National-Anti-national, India-Pakistan and derail the public discourse from issues and logic into polarizing emotions. You all know exactly which ones, and you all even know the debaters who’re being rewarded for spewing the vilest propaganda.

7. The polarization – all the message of development is gone. BJP’s strategy for the next election is polarization and inciting pseudo-nationalism. Modi-ji has basically said it himself in speeches – Jinnah; Nehru; Congress leaders didn’t meet Bhagat Singh in jail (fake news from the PM himself!); INC leaders met leaders in Pakistan to defeat Modi in Gujarat; Yogi-ji’s speech on how Maharana Pratap was greater than Akbar; Jawaharlal Univerity students are anti-national they’ll #TukdeTukdeChurChur India – this is all propaganda constructed for a very specific purpose: polarize and win elections. It isn’t the stuff I want to be hearing from my leaders and I refuse to follow anyone who is willing to let the nation burn in riots for political gain.

These are just some of the instances of how BJP is pushing the national discourse in a dark corner. This isn’t something I signed up for and it totally isn’t something I can support. That is why I am resigning from BJP.

PS: I supported BJP since 2013 because Narendra Modi-ji seemed like a ray of hope for India and I believed in his message of development – that message and the hope are now both gone. The negatives of this Narendra Modi and Amit Shah government now outweigh the positives for me, but that is a decision that every voter needs to make individually. Just know that history and reality are complicated. Buying into simplistic propaganda and espousing cult-like unquestioning faith are the worst thing you can do – it is against the interests of democracy and of this nation.

You all have your own decisions to make as the elections approach. Best of luck with that. My only hope is that we can all live and work harmoniously together, and contribute towards making a better, stronger, poverty-free and developed India, no matter what party or ideology we support. Always remember that there are good people on both sides, the voter needs to support them and they need to support each other even when they are in different parties.

Friday, 21 November 2014

Big supermarkets may be dying but they leave a plague on the landscape

Wednesday, 24 July 2013

Australian Cricket: hubris, despair, panic

| |||

Related Links

Players/Officials: Michael Clarke | Darren Lehmann

Series/Tournaments: Australia tour of England and Scotland

| |||

The idea will not leave me alone. A sneaking question keeps coming into my head: are Australia losing their cricketing edge? And I don't just mean the Ashes. I mean the whole legend of the Aussie battler that has been constructed over decades of flinty toughness…[Once] self-reliance was as central as toughness. Rod Marsh's coaching advice was simple: "Sort it out for yourself." That spirit ran through the great tradition. Bradman taught himself to bat by hitting a golf ball against a wall with a stick. Learning to bat was another form of looking after yourself, like pitching a tent in the outback. That resilience was compounded by the sense that Australians had a point to prove, that the world too often underestimated them. Cricket was a means of getting even…I was brought up on the received wisdom that it was the Australian system that made them so tough - the strong club cricket, the fierce inter-state rivalries. Each has now declined, at least to some extent. It may be a very long time indeed - a full turn of the dynastic wheel - before Australia will again be able to boast such a record of dominance.

let us leave behind the soap opera, the tidbits of gossip and intrigue. No causal truths reside there. What David Warner's brother thinks of Shane Watson did not lose Australia the Test match, nor did the sacking of Arthur, nor homework-gate, nor an incident in a nightclub

Wednesday, 26 June 2013

Politicians who demand inquiries should be taken out and shot