At the start of the 2008 academic year, Pablo Iglesias, a 29-year-old lecturer with a pierced eyebrow and a ponytail greeted his students at the political sciences faculty of the Complutense University in Madrid by inviting them to stand on their chairs. The idea was to re-enact a scene from the film Dead Poets Society. Iglesias’s message was simple. His students were there to study power, and the powerful can be challenged. This stunt was typical of him. Politics, Iglesias thought, was not just something to be studied. It was something you either did, or let others do to you. As a professor, he was smart, hyperactive and – as a founder of a university organisation called Counter-Power – quick to back student protest. He did not fit the classic profile of a doctrinaire intellectual from Spain’s communist-led left. But he was clear about what was to blame for the world’s ills: the unfettered, globalised capitalism that, in the wake of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, had installed itself as the developed world’s dominant ideology.

Iglesias and the students, ex-students and faculty academics worked hard to spread their ideas. They produced political television shows and collaborated with their Latin American heroes – left-leaning populist leaders such as Rafael Correa of Ecuador or Evo Morales of Bolivia. But when they launched their own political party on 17 January 2014 and gave it the name Podemos (“We Can”), many dismissed it. With no money, no structure and few concrete policies, it looked like just one of several angry, anti-austerity parties destined to fade away within months.

A year later, on 31 January 2015, Iglesias strode across a stage in Madrid’s emblematic central square, the Puerta del Sol. It was filled with 150,000 people, squeezed in so tightly that it was impossible to move. He addressed the crowd with the impassioned rhetoric for which opponents have branded him a dangerous leftwing populist. He railed against the monsters of “financial totalitarianism” who had humiliated them all. He told Podemos’s followers to dream and, like that noble madman Don Quixote, “take their dreams seriously”.Spain was in the grip of historic, convulsive change. The serried crowd were heirs to the common folk who – armed with knives, flowerpots and stones – had rebelled against Napoleonic troops in nearby streets two centuries earlier. “We can dream, we can win!” he shouted.

Polls suggest that he is right. Since 1982, Spain has been governed by only two parties. Yet El País newspaper now places Podemos at 22%, ahead of both the ruling conservative Partido Popular (PP) and its leftwing opposition Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE). If Podemos can grow further, Iglesias could become prime minister after elections that are expected in November. This would be an almost unheard-of achievement for such a young party.

Many in the Puerta del Sol longed to see that day. “Yes we can! Yes we can!” they chanted. Other onlookers shivered, recalling Iglesias’s praise for Venezuela’s late president Hugo Chávez and fearing an eruption of Latin American-style populism in a country gripped by debt, austerity and unemployment. But without Podemos, supporters feared, Spain faced the prospect of becoming like Greece, with its disintegrating welfare state, crumbling middle class and rampant inequality.

On stage that day, Iglesias declared that Podemos would take back power from self-serving elites and hand it over to the people. To do that, the new party needs votes. If that means arousing emotions and being accused of populism, so be it. And, as the party’s founders have already shown, if they have to renounce some of their ideas in order to broaden their appeal, or risk upsetting some in their grassroots movement by tightening central control, they are ready to do that, too. The aim, after all, is to win.

At first glance, Podemos’s dizzying rise looks miraculous. In truth, the project evolved over a long time, though even the organisers did not know it would eventually spawn a party, or that a global financial crisis would provide their opportunity. In Spain today, one-third of the labour force is either jobless or earns less than the minimum annual salary of €9,080. In big cities, the sight of people raiding bins for food or things to sell – a rarity in pre-crisis Spain – is no longer shocking. A fatalistic gloom has settled over a country that rode a wave of optimism for three decades after it transformed itself from dictatorship to democracy. After years of economic growth, the financial crisis burst Spain’s construction bubble. Countless corruption cases – involving both the PP and PSOE – have stoked widespread anger towards the established political class. “A political crisis is a moment for daring,” Iglesias told an audience recently. “It is when a revolutionary is capable of looking people in the eye and telling them, ‘Look, those people are your enemies.’”

He is not the first Pablo Iglesias to shake Spain’s political order. He is named after the man who founded the PSOE in 1879. (His parents first met at a remembrance ceremony in front of Iglesias’s tomb.) As a teenager, Iglesias was a member of the Communist Youth in Vallecas, one of Madrid’s poorest and proudest barrios. He still lives there today, in a modest apartment on a graffiti-daubed 1980s estate of medium- and high-rise blocks. (“Defend your happiness, organise your rage,” reads one graffiti slogan.) Even as a teenager, he was “a leader and great seducer”, recalled a senior Podemos member who had attended the same youth group. Iglesias studied law at the Complutense University before taking a second undergraduate degree in political science. He went on to write a PhD thesis on disobedience and anti-globalisation protests that was awarded a prestigious cum laude grade

.

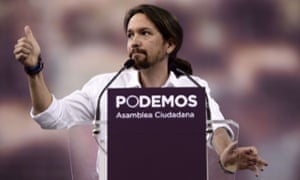

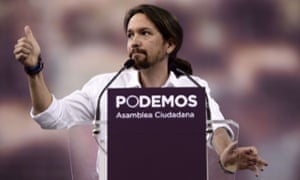

Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias rails against the monsters of ‘financial totalitarianism’, and tells the party’s followers to ‘take their dreams seriously’. Photograph: Dani Pozo/AFP/Getty

It was at Complutense, where he began to lecture after receiving his doctorate, that Iglesias met the key figures who would help him found Podemos. Deeply influenced by Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist thinker who argued that a key battle was over the machinery that shaped public opinion, this group also found inspiration at the University of Essex. There, the Argentine academic Ernesto Laclau began in the 1970s to write a series of works on Marxism, populism and demoracy which, along with work by his Belgian wife Chantal Mouffe (now at the University of Westminister), have had a profound impact on Podemos’s leadership. Their complex 1985 book, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, remains a key point of reference for Podemos’s leadership.

Socialism, Laclau and Mouffe argued, should no longer focus on class warfare. Instead, socialists should seek to unite discontented groups – such as feminists, gay people, environmentalists, the unemployed – against a clearly defined enemy, usually the establishment. One way of doing this was through a charismatic leader who would fight the powerful on behalf of the underdogs. Laclau and Mouffe encouraged this new left to appeal to voters with simple, emotionally engaging rhetoric. They argued that liberal elites decry such tactics as populism because they are scared of ordinary people becoming involved in politics.

“There is too much consensus and not enough dissent [in leftwing politics],” said Mouffe, an elegant 71-year-old, at her London apartment in February. To her, the rise of rightwing populists such as Marine Le Pen’s Front National in France or Nigel Farage’s Ukip in the UK is proof that the post-Thatcherite consensus – cemented by “third way” social democrats such as Tony Blair – has left a dangerous vacuum. “The choice today is between rightwing or leftwing populism,” Mouffe told Iglesias in a TV interview in February.

If Iglesias had long seen neoliberals as the enemy and social democrats as sellouts, he eventually came to view the traditional far left as well-meaning fools. They damned television as lowbrow and manipulative, refusing to see that people’s politics were increasingly defined by the media they consumed rather than by loyalty to parties. This was something Spain’s aggressive far-right pundits had grasped in the mid-2000s, setting up television channels that exercised much the same pressure on the PP as Fox News does on the Republicans in the US. Iglesias believed it was time for the left to do something similar.

In May 2010 he organised a faculty debate that limited speakers to turns of 99 seconds. He named the event after the ska anthem One Step Beyond. Iglesias asked Tele-K, a neighbourhood TV channel partly housed in a disused Vallecas garage, to record them. “I was amazed by Pablo’s skills as a presenter, and by the care they had taken in setting it up,” Tele-K director Paco Pérez told me. He was sufficiently impressed to invite Iglesias to produce and present a debate series. Iglesias and his small team of students and activists took the idea seriously, although the station’s audience was tiny. “Pablo would even rehearse – something we’d never seen,” said Pérez. “The amazing thing was that we started to get a big online audience. It became a cult show.” La Tuerka (a play on the Spanish word for nut or screw), an initially earnest round-table debate show, became the seed for Podemos.

* * *

On 15 May 2011, Íñigo Errejón, the man who would become Podemos’s No 2, reached Madrid from Quito, Ecuador. Errejón was days away from presenting a PhD thesis at Complutense University that linked the success of Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, to the ideas of Gramsci, Mouffe and Laclau. Friends suggested that he head straight to the Puerta del Sol, where something extraordinary was happening.

Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias rails against the monsters of ‘financial totalitarianism’, and tells the party’s followers to ‘take their dreams seriously’. Photograph: Dani Pozo/AFP/Getty

It was at Complutense, where he began to lecture after receiving his doctorate, that Iglesias met the key figures who would help him found Podemos. Deeply influenced by Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist thinker who argued that a key battle was over the machinery that shaped public opinion, this group also found inspiration at the University of Essex. There, the Argentine academic Ernesto Laclau began in the 1970s to write a series of works on Marxism, populism and demoracy which, along with work by his Belgian wife Chantal Mouffe (now at the University of Westminister), have had a profound impact on Podemos’s leadership. Their complex 1985 book, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, remains a key point of reference for Podemos’s leadership.

Socialism, Laclau and Mouffe argued, should no longer focus on class warfare. Instead, socialists should seek to unite discontented groups – such as feminists, gay people, environmentalists, the unemployed – against a clearly defined enemy, usually the establishment. One way of doing this was through a charismatic leader who would fight the powerful on behalf of the underdogs. Laclau and Mouffe encouraged this new left to appeal to voters with simple, emotionally engaging rhetoric. They argued that liberal elites decry such tactics as populism because they are scared of ordinary people becoming involved in politics.

“There is too much consensus and not enough dissent [in leftwing politics],” said Mouffe, an elegant 71-year-old, at her London apartment in February. To her, the rise of rightwing populists such as Marine Le Pen’s Front National in France or Nigel Farage’s Ukip in the UK is proof that the post-Thatcherite consensus – cemented by “third way” social democrats such as Tony Blair – has left a dangerous vacuum. “The choice today is between rightwing or leftwing populism,” Mouffe told Iglesias in a TV interview in February.

If Iglesias had long seen neoliberals as the enemy and social democrats as sellouts, he eventually came to view the traditional far left as well-meaning fools. They damned television as lowbrow and manipulative, refusing to see that people’s politics were increasingly defined by the media they consumed rather than by loyalty to parties. This was something Spain’s aggressive far-right pundits had grasped in the mid-2000s, setting up television channels that exercised much the same pressure on the PP as Fox News does on the Republicans in the US. Iglesias believed it was time for the left to do something similar.

In May 2010 he organised a faculty debate that limited speakers to turns of 99 seconds. He named the event after the ska anthem One Step Beyond. Iglesias asked Tele-K, a neighbourhood TV channel partly housed in a disused Vallecas garage, to record them. “I was amazed by Pablo’s skills as a presenter, and by the care they had taken in setting it up,” Tele-K director Paco Pérez told me. He was sufficiently impressed to invite Iglesias to produce and present a debate series. Iglesias and his small team of students and activists took the idea seriously, although the station’s audience was tiny. “Pablo would even rehearse – something we’d never seen,” said Pérez. “The amazing thing was that we started to get a big online audience. It became a cult show.” La Tuerka (a play on the Spanish word for nut or screw), an initially earnest round-table debate show, became the seed for Podemos.

* * *

On 15 May 2011, Íñigo Errejón, the man who would become Podemos’s No 2, reached Madrid from Quito, Ecuador. Errejón was days away from presenting a PhD thesis at Complutense University that linked the success of Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, to the ideas of Gramsci, Mouffe and Laclau. Friends suggested that he head straight to the Puerta del Sol, where something extraordinary was happening.

Demonstrators gather near Madrid’s Puerta del Sol for a ‘March for Change’ organised by Podemos in January. Photograph: Gerard Julien/AFP/Getty

Somehow a protest march had turned into a camp that eventually drew tens of thousands of protesters. The indignados, who would inspire the Occupy movement, then took over city squares across the country, railing against politicians. “They don’t represent us!” became the rallying cry. Polls showed that 80% of the public backed the protestors. Some even carried Spain’s red-and-gold flag, a sign that this was bigger than the standard leftwing protests at which the purple, gold and red flag of Spain’s long-lost Republic usually dominated. The indignados debated at open-air assemblies, taking turns to speak and using hand gestures – raised waving hands for “yes”, crossed arms for “no” – to express agreement or disagreement.

For Iglesias and his fellow theorists at Complutense University, the protests made perfect sense. The consensus between Spain’s two biggest parties around German-imposed austerity had turned many citizens into political orphans, with no one to represent them. “Those with the power still governed, but they no longer convinced people,” Errejón told me recently.

Still, a month after the protests began, the squares had emptied. Six months later, at the end of 2011, Spain elected a new government, amid warnings that, whoever won, German chancellor Angela Merkel would be in charge. Disillusioned voters saw that even the PSOE offered little more than cowed obedience to Merkel’s demands for more austerity. Following a low turnout, Mariano Rajoy’s PP won an absolute majority and introduced further cuts while slowly taming budget deficits that had topped 11%. The indignado spirit, it seemed, had been crushed.

In fact, indignado assemblies continued to meet, and for the most politically active, La Tuerka became essential viewing. With time, the show moved to the online news site Público, and became more polished. Each show would begin with Iglesias or his fellow Complutense professor Juan Carlos Monedero delivering a monologue, followed by debate and rap music. When Iran’s state-run Spanish-language television service, HispanTV, asked for an Iglesias-presented show, starting in January 2013, the team jumped at it. The show, called Fort Apache, opened with Iglesias astride a Harley Davidson Sportster motorbike, placing a helmet over his head and – after a close-up of his eyes – slinging a massive crossbow across his back before roaring off. “Watch your head, white man. This is Fort Apache!” he warned in the trailers. They were still, however, preaching mostly to a small number of the already converted.

All that changed on 25 April 2013, when Iglesias appeared on a rightwing debate show on the small channel Intereconomia. “It is a pleasure to cross enemy lines and talk,” said Iglesias by way of introduction. He was outnumbered. He would be debating against four conservative pundits. But Iglesias had come prepared and acquitted himself well. Soon, he was receiving invitations to appear on debate shows on Spain’s mainstream channels. Ratings surged as Iglesias, equipped with endless facts and a series of simple messages, wiped the floor with fellow debaters. The cocksure young lecturer usually sat with one ankle resting on a knee and an arm casually thrown behind his chair, his smile occasionally slipping into condescension. He repeated, mantra-like, that the blame for Spain’s woes lay with “la casta”, his name for the corrupt political and business elites he claimed had sold the country to the banks. The other enemy was Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel and the unelected officials who oversaw the euro from the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. Iglesias did not want Spain to leave the European Union, but he was not satisfied with it either. Above all, he wanted Spaniards to recover “sovereignty”, a concept that, like many others, remained fuzzy.

Ratings surged as Iglesias, equipped with endless facts and simple messages, wiped the floor with fellow debaters

A media star had been born. Many knew him just as “el coletas” (“the pony-tailed one”). Iglesias had spent years honing his technique, doing theatre and even attending a presenter’s course at state television RTVE’s academy. Communication, he had already declared in his PhD thesis, was key to protest. For years he and Monedero had been telling Spain’s communist-led leftwing coalition Izquierda Unida (IU) that it should learn from the Latin Americans and widen its appeal. Now they proposed a broad leftwing movement, with open primaries at which outside candidates such as Iglesias could stand. They received a firm no from IU leader Cayo Lara, who later declared that Iglesias had “the principles of Groucho Marx”. So they created it themselves.

* * *

The Podemos plan was cemented over a dinner in August 2013, during the four-day “summer university” of a tiny, radical party called Izquierda Anticapitalista (IA). Iglesias and IA heavyweight Miguel Urbán, then a then 33-year-old veteran of multiple protest movements agreed to work together, creating the strange and tense marriage between a single, charismatic leader – Iglesias – and an organisation that hates hierachy. “Pablo had political and media prestige, but that was not enough,” Urbán told me. “We needed an organisational base that stretched across the country, and that was IA.”

The plan was daring and highly improbable. It was to be an 18-month assault on power, with the ultimate aim being to replace the PSOE as leaders of the left and unseat Prime Minister Rajoy at the 2015 general election. The core clique of like-minded academics from the Complutense political sciences faculty, who were veterans of La Tuerka, would manage the campaign. At last, they would be able to try out their ideas on a national scale.

The first test for Podemos would be the May 2014 European elections. Many voters view the European parliament as toothless because the EU’s major decisions are taken elsewhere. With so little at stake, they take risks in the polling booth. Iglesias and Urbán saw the European elections as a potential springboard for their 2015 general election campaign. The party’s name – which echoes not just Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign slogan, but also a TV jingle for Spain’s European and World Cup-winning football team – came during a car journey a few months after the forming of the initial pact between Iglesias and Urbán. “We thought of ‘Yes you can!’, but that already existed,” said Urbán. “So then we went for Podemos [We Can]. It was nicely affirmative.”

On January 17 2014, Iglesias officially announced the creation of Podemos at a small theatre in Lavapiés, the hip Madrid district that over the past decade has filled up with alternative bookshops, galleries and bars. Iglesias (his eyebrow stud now removed in order to improve his electoral image) explained that a cornerstone of the Podemos project would be indignado-style “circles”, or assemblies. These circles, built around local communities or shared political interests, could meet, debate or vote in person or online. He told the crowd that if 50,000 people signed a petition on the Podemos website, he would lead a list of candidates at the European parliamentary elections in May. The target was reached within 24 hours, despite the website crashing for part of that time.

Pablo Echenique got involved with Podemos via its regional ‘circles’, and was elected as an MEP in 2014. Photograph: Jose Luis Cuesta/Cordon Press/Corbis

The Podemos project was born with two contradictions that would become increasingly apparent over time. First, it would be both radical and pragmatic in its pursuit of power. Second, it pledged to hand control to grassroots activists, despite the fact the party depended on one man’s popularity. But at the beginning, these tensions were far from most people’s minds. Excitement and idealism were the norm.

Pablo Echenique, a research physicist with spinal muscular atrophy, saw the Lavapiés speech on YouTube at his home in Zaragoza, central Spain. Three years earlier, Echenique had bumped along Zaragoza’s streets in his electric wheelchair to join the indignado protesters. He was excited by the debates, but frustrated by the lack of action. “They had no bite,” he told me. “There was no answer about what to do next.” When, four days after the Lavapiés speech, Iglesias travelled to a cultural centre beside Plaza San Agustín in Zaragoza for his first European election campaign meeting , Echenique got there early, but the 180-seat hall filled quickly. “Soon there were 500 people outside, so Pablo said: ‘I know it’s cold, but it’s worse not to have a job. We don’t fit here, so let’s go out into the plaza.’ It was freezing.”

It was in Zaragoza that Urbán first realised that Podemos might succeed. “As I waited at the door, someone asked whether I was from Podemos in Zaragoza,” Urbán told me. “I was in charge of Podemos’s organisation, but thought we didn’t really exist yet, so I just said I had come from Madrid. He replied, ‘Well, I’m from Podemos in Calatayud.’ That’s a town with just 20,000 inhabitants. Suddenly I realised that something really had changed. It was the political equivalent of occupying the squares.” A pattern was set, of packed campaign meetings that were generally ignored by the press. For those involved, it was exhilarating. Urbán took home the money gathered at the meetings to count. “We would get €2,000 from a single meeting. It was like belonging to a church,” he said.

Iglesias said politics was like sex: you start off doing it badly, but learn with experience

Echenique was inspired. “I told Pablo, ‘You say we should get organised, but I’ve never been in an organised political party. Can you give me some ideas?’ Pablo said it was like sex: you start off doing it badly, but learn with experience.” Echenique joined two circles, one in Zaragoza and one online-based group for people with disabilities. He was one of 150 candidates put forward by circles for the European parliament. These were ranked in order by 33,000 people who signed on for free to the party website. Iglesias came first and Echenique was fifth. Only one of the top 12 candidates was over 36 years old.

Podemos then embarked on the complex process of writing a “participative” election manifesto, based on ideas from the circles and then voted for online. The result was original, but also impractical and uncosted. It called for a basic state salary for all citizens and non-payment of “illegitimate” parts of the public debt, although the manifesto did not specify which parts these were – two measures that Podemos has since back-pedalled on.

The Podemos project was born with two contradictions that would become increasingly apparent over time. First, it would be both radical and pragmatic in its pursuit of power. Second, it pledged to hand control to grassroots activists, despite the fact the party depended on one man’s popularity. But at the beginning, these tensions were far from most people’s minds. Excitement and idealism were the norm.

Pablo Echenique, a research physicist with spinal muscular atrophy, saw the Lavapiés speech on YouTube at his home in Zaragoza, central Spain. Three years earlier, Echenique had bumped along Zaragoza’s streets in his electric wheelchair to join the indignado protesters. He was excited by the debates, but frustrated by the lack of action. “They had no bite,” he told me. “There was no answer about what to do next.” When, four days after the Lavapiés speech, Iglesias travelled to a cultural centre beside Plaza San Agustín in Zaragoza for his first European election campaign meeting , Echenique got there early, but the 180-seat hall filled quickly. “Soon there were 500 people outside, so Pablo said: ‘I know it’s cold, but it’s worse not to have a job. We don’t fit here, so let’s go out into the plaza.’ It was freezing.”

It was in Zaragoza that Urbán first realised that Podemos might succeed. “As I waited at the door, someone asked whether I was from Podemos in Zaragoza,” Urbán told me. “I was in charge of Podemos’s organisation, but thought we didn’t really exist yet, so I just said I had come from Madrid. He replied, ‘Well, I’m from Podemos in Calatayud.’ That’s a town with just 20,000 inhabitants. Suddenly I realised that something really had changed. It was the political equivalent of occupying the squares.” A pattern was set, of packed campaign meetings that were generally ignored by the press. For those involved, it was exhilarating. Urbán took home the money gathered at the meetings to count. “We would get €2,000 from a single meeting. It was like belonging to a church,” he said.

Iglesias said politics was like sex: you start off doing it badly, but learn with experience

Echenique was inspired. “I told Pablo, ‘You say we should get organised, but I’ve never been in an organised political party. Can you give me some ideas?’ Pablo said it was like sex: you start off doing it badly, but learn with experience.” Echenique joined two circles, one in Zaragoza and one online-based group for people with disabilities. He was one of 150 candidates put forward by circles for the European parliament. These were ranked in order by 33,000 people who signed on for free to the party website. Iglesias came first and Echenique was fifth. Only one of the top 12 candidates was over 36 years old.

Podemos then embarked on the complex process of writing a “participative” election manifesto, based on ideas from the circles and then voted for online. The result was original, but also impractical and uncosted. It called for a basic state salary for all citizens and non-payment of “illegitimate” parts of the public debt, although the manifesto did not specify which parts these were – two measures that Podemos has since back-pedalled on.

.

Alexis Tsipras (left), leader of Greece’s Syriza party and now the country’s prime minister, with Podemos leader Igelsias. Photograph: Lefteris Pitarakis/AP

Little more than a month before the European elections, Podemos’s own polling revealed that only 8% of Spaniards had heard of them. However, 50% knew who Pablo Iglesias was. The party took the controversial step of changing its logo, putting Iglesias’s face on it to ensure it would go on the ballot slips. Eighteen days before the vote, the state-run pollster CIS said Podemos might scrape one seat.

On the night of the election, Podemos surprised everybody. It took 8% of the vote, with Iglesias, Echenique and three others becoming MEPs. Amid all the celebration, Iglesias remained cool. The PP was still in government, he warned. The battle had only just begun.

* * *

Eight months after the elections, on a flight back to Madrid from Athens in January, Iglesias sat, as he always does, in a budget seat. He had just helped Alexis Tsipras of Syriza close a campaign rally with a line by Leonard Cohen – “First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin” – and a few well-pronounced words in Greek. It was an early start after a late night, but he was already in work mode. “I drink Red Bull so that I can read on long flights,” he said in the lounge, as a Greek businessman who owned restaurants in Madrid insisted on paying for our cafe freddo at the coffee kiosk and enthused about the changes coming to both countries.

In person, Iglesias’s combative public persona gives way to careful politeness (“Like the perfect son-in-law,” according to Mouffe). Unlike other leading politicians, he refuses to ride around in official cars, but he has lost his freedom to walk down the street or go into a bar without being stopped. When we arrived at Madrid’s Barajas airport, a lottery ticket vendor who caught sight of him stopped in her tracks. “You don’t have to buy. Just win!” she said, eyes bulging.

Iglesias was energised by his Athens visit, but Tsipras had been less effusive the night before, when, at a party on the terrace of a nightclub with spectacular views of the Parthenon, I asked him whether a future Podemos victory was key toSyriza. Not really, he answered. “Their elections are not for a while,” said the man who, three days later, became Europe’s lone austerity rebel. “I think we will open roads for them.”

Spain is not Greece. Austerity may be hurting – the Roman Catholic charity Caritas distributed food, clothes and help to 2.5 million people (one in 20 Spaniards) last year – but it has not produced the scenes of deprivation that one regularly sees on the streets of Athens, such as the queues at charity pharmacies where those excluded from state medical care go for medicines. Still, “if this can happen to us,” said Iliopoulou Vassiliki, a pharmacy volunteer, expressing a fear shared by many Podemos supporters, “who will be next?”

A few days after Iglesias returned from Athens, Iglesias visited Valencia for a rally. Podemos will win much of the youth vote at the general election, but those who attend their rallies – many of them members of local Podemos circles – are mostly older. Activism comes more easily to those in their forties and above, many of whom recall the heady early years of Spain’s democratic transition and are surprised by the younger generation’s passivity. Loudspeakers pumped out Patti Smith’s People Have the Power to 8,000 people packed into the basketball stadium. “Here comes the rockstar moment,” warned a Spanish journalist as Iglesias and Errejón appeared to raucous applause. A middle-aged woman in leopardskin-print trousers bellowed: “Presidente! Presidente!” Someone else shouted: “Long live the mother who gave birth to you!”

As capital of a region notorious for political corruption, Valencia is fertile ground for Podemos. Iglesias read out a letter from Nerea, a girl who was there on her ninth birthday. “We like you because you help people,” it said. “Thank you for giving my parents hope again.” The father held the girl above his head. “They [the establishment] aren’t afraid of me, Nerea. They are afraid of you and families who have said, ‘That’s enough!’,” said Iglesias, before segueing into a series of slogans: “The smiles have changed sides”; “Of course we can!” John Carlin, an El País writer, says Iglesias is selling a religious tale similar to that of Jesus expelling the money changers. The implication is that Podemos’s followers prefer the uplifting feeling of shared faith to cool reason. I recalled a volunteer in a Podemos office in Madrid who surprised me by confiding that he would not vote for them. “There is too much emotion,” he said.

Podemos activist Irene Camps had come to the rally with circle members from Manises, a struggling industrial town near Valencia’s airport where a former PP mayor is being tried for (which he denies). One evening a few weeks after the rally, Camps and I stood outside the local Consum supermarket with half a dozen women who were waiting to go through its bins for food. Nearby, a huge theatre, the construction of which started during Spain’s boom days before the 2007 crash, sat unfinished. “Everyone’s talking about Podemos. We should give them a chance,” said Paqui Fernández, the women’s self-appointed leader. She and her friends recalled that this land was occupied by “cave-houses” – homes built from holes in the rock – in the 1950s. It was a reminder of how far Spain has come since the death of Francisco Franco in 1975, but also that memories of poverty are not that old. Camps is part of Spain’s recently expanded, but now shrinking and scared, middle class. “If we don’t change things,” she said. “I’ll end up like Paqui.”

The party’s use of transparency websites, voting tools and online debate is already cutting-edge

The next day, bathed in winter sunshine, Camps helped at an open-air Podemos assembly on a ramshackle estate of detached houses in countryside outside Manises. Timid locals stepped into a circle of earnest, purple-shirted activists and were applauded for airing their fears. The party’s 900-odd circles are key to Podemos’s participative approach and local popularity, but they are hard to control. (The party still does not have a full list of them.) Anyone can join in and vote.

If Podemos wants to be more than a traditional party or a top-heavy populist movement then it must deliver on direct democracy. The party’s use of transparency websites (detailing all spending, including salaries), voting tools and online debate is already cutting-edge. Its Plaza Podemos debating site regularly attracts between 10,000 and 20,000 daily visitors. “Nothing on this scale using online tools is happening anywhere else in the world,” Ben Knight, one of the entrepreneurs behind a collaborative decision-making app, Loomio, told me.

Alexis Tsipras (left), leader of Greece’s Syriza party and now the country’s prime minister, with Podemos leader Igelsias. Photograph: Lefteris Pitarakis/AP

Little more than a month before the European elections, Podemos’s own polling revealed that only 8% of Spaniards had heard of them. However, 50% knew who Pablo Iglesias was. The party took the controversial step of changing its logo, putting Iglesias’s face on it to ensure it would go on the ballot slips. Eighteen days before the vote, the state-run pollster CIS said Podemos might scrape one seat.

On the night of the election, Podemos surprised everybody. It took 8% of the vote, with Iglesias, Echenique and three others becoming MEPs. Amid all the celebration, Iglesias remained cool. The PP was still in government, he warned. The battle had only just begun.

* * *

Eight months after the elections, on a flight back to Madrid from Athens in January, Iglesias sat, as he always does, in a budget seat. He had just helped Alexis Tsipras of Syriza close a campaign rally with a line by Leonard Cohen – “First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin” – and a few well-pronounced words in Greek. It was an early start after a late night, but he was already in work mode. “I drink Red Bull so that I can read on long flights,” he said in the lounge, as a Greek businessman who owned restaurants in Madrid insisted on paying for our cafe freddo at the coffee kiosk and enthused about the changes coming to both countries.

In person, Iglesias’s combative public persona gives way to careful politeness (“Like the perfect son-in-law,” according to Mouffe). Unlike other leading politicians, he refuses to ride around in official cars, but he has lost his freedom to walk down the street or go into a bar without being stopped. When we arrived at Madrid’s Barajas airport, a lottery ticket vendor who caught sight of him stopped in her tracks. “You don’t have to buy. Just win!” she said, eyes bulging.

Iglesias was energised by his Athens visit, but Tsipras had been less effusive the night before, when, at a party on the terrace of a nightclub with spectacular views of the Parthenon, I asked him whether a future Podemos victory was key toSyriza. Not really, he answered. “Their elections are not for a while,” said the man who, three days later, became Europe’s lone austerity rebel. “I think we will open roads for them.”

Spain is not Greece. Austerity may be hurting – the Roman Catholic charity Caritas distributed food, clothes and help to 2.5 million people (one in 20 Spaniards) last year – but it has not produced the scenes of deprivation that one regularly sees on the streets of Athens, such as the queues at charity pharmacies where those excluded from state medical care go for medicines. Still, “if this can happen to us,” said Iliopoulou Vassiliki, a pharmacy volunteer, expressing a fear shared by many Podemos supporters, “who will be next?”

A few days after Iglesias returned from Athens, Iglesias visited Valencia for a rally. Podemos will win much of the youth vote at the general election, but those who attend their rallies – many of them members of local Podemos circles – are mostly older. Activism comes more easily to those in their forties and above, many of whom recall the heady early years of Spain’s democratic transition and are surprised by the younger generation’s passivity. Loudspeakers pumped out Patti Smith’s People Have the Power to 8,000 people packed into the basketball stadium. “Here comes the rockstar moment,” warned a Spanish journalist as Iglesias and Errejón appeared to raucous applause. A middle-aged woman in leopardskin-print trousers bellowed: “Presidente! Presidente!” Someone else shouted: “Long live the mother who gave birth to you!”

As capital of a region notorious for political corruption, Valencia is fertile ground for Podemos. Iglesias read out a letter from Nerea, a girl who was there on her ninth birthday. “We like you because you help people,” it said. “Thank you for giving my parents hope again.” The father held the girl above his head. “They [the establishment] aren’t afraid of me, Nerea. They are afraid of you and families who have said, ‘That’s enough!’,” said Iglesias, before segueing into a series of slogans: “The smiles have changed sides”; “Of course we can!” John Carlin, an El País writer, says Iglesias is selling a religious tale similar to that of Jesus expelling the money changers. The implication is that Podemos’s followers prefer the uplifting feeling of shared faith to cool reason. I recalled a volunteer in a Podemos office in Madrid who surprised me by confiding that he would not vote for them. “There is too much emotion,” he said.

Podemos activist Irene Camps had come to the rally with circle members from Manises, a struggling industrial town near Valencia’s airport where a former PP mayor is being tried for (which he denies). One evening a few weeks after the rally, Camps and I stood outside the local Consum supermarket with half a dozen women who were waiting to go through its bins for food. Nearby, a huge theatre, the construction of which started during Spain’s boom days before the 2007 crash, sat unfinished. “Everyone’s talking about Podemos. We should give them a chance,” said Paqui Fernández, the women’s self-appointed leader. She and her friends recalled that this land was occupied by “cave-houses” – homes built from holes in the rock – in the 1950s. It was a reminder of how far Spain has come since the death of Francisco Franco in 1975, but also that memories of poverty are not that old. Camps is part of Spain’s recently expanded, but now shrinking and scared, middle class. “If we don’t change things,” she said. “I’ll end up like Paqui.”

The party’s use of transparency websites, voting tools and online debate is already cutting-edge

The next day, bathed in winter sunshine, Camps helped at an open-air Podemos assembly on a ramshackle estate of detached houses in countryside outside Manises. Timid locals stepped into a circle of earnest, purple-shirted activists and were applauded for airing their fears. The party’s 900-odd circles are key to Podemos’s participative approach and local popularity, but they are hard to control. (The party still does not have a full list of them.) Anyone can join in and vote.

If Podemos wants to be more than a traditional party or a top-heavy populist movement then it must deliver on direct democracy. The party’s use of transparency websites (detailing all spending, including salaries), voting tools and online debate is already cutting-edge. Its Plaza Podemos debating site regularly attracts between 10,000 and 20,000 daily visitors. “Nothing on this scale using online tools is happening anywhere else in the world,” Ben Knight, one of the entrepreneurs behind a collaborative decision-making app, Loomio, told me.

Spain has not suffered the same deprivations as Greece, but austerity is hurting, and there is widespread anger towards the established political class. Photograph: Pablo Blazquez Dominguez/Getty Images

But on the wider use of direct democracy, as with other matters, Podemos does not yet have a settled strategy. The only fixed principles are that senior party members, including Iglesias, should be sackable by referendum, and that post-electoral coalitions must be voted on by supporters. Whether Podemos can balance the demands of its grassroots activists, who expect to shape policy, with the powerful influence of Iglesias and his clique of Complutense academics, remains one of the most challenging questions for the party’s future.

When it came to finally deciding on the party’s structure at an open assembly last autumn, Iglesias’s team wanted a strong leader. Echenique’s rival proposal for a shared, three-person leadership gained the backing of many activist circles, but won just a fifth of the 112,000 votes cast online. “You could say that Iglesias got the more superficial votes,” said Miguel Arana Catania of LaboDemo, a digital consultancy that advises Podemos. “These were the people who had seen him on television.” It is only at a local level, or when turnout is low, that the Complutense group loses control.

* * *

Charismatic leadership is hardwired into Podemos. Senior members admit the project would be impossible without Iglesias’s vision, television skills and leadership. That does not make him a Hugo Chávez, as some would like to claim, but it does raise questions about how much power he might accumulate. “I am not irreplaceable,” Iglesias himself has declared. “I’m an activist, not an alpha male, and I place myself under the orders of the majority.”

Members of his close-knit team of 60 people, who have mostly worked out of cramped offices with curling carpets and broken doorbells, often profess undying loyalty. “I take attacks on him personally,” admitted one. Many of his team have shed their studies, careers or relationships over the past year as the Podemos project has taken off. Those with children – a tiny minority, since the average age is 26 – complain that the work is too draining. Men predominate, though the party presents “zipper” lists of candidates (so-called after the teeth of a zip), with men and women alternating, for public posts. Others who would like to work for Podemos say the salary cap of €1,900 per month is prohibitive. (Earnings above that from public positions are donated to the party and other causes.)

Iglesias is aware of the paradox of a party with anti-capitalist roots bidding to administer a market-based economy

Podemos has a new Madrid headquarters a few floors down from the scruffy rooms where it had set up camp after the European elections. It was in this bland office block that, 13 months after founding his party, Iglesias agreed to meet for a sit-down interview. “At last, the world’s most sought-after man,” joked one of his staff as we waited outside his door. Iglesias looked oddly out of place in this pristine but anodyne new home, with its hotel-style fitted carpets and shiny wooden doors. His bracelets and his hair, neatly gathered in a colourful elasticated band, contrast with his unflashy day-to-day uniform of checked shirts, jeans or cheap chinos and trainers. (“None of them are interested in money,” a fellow lecturer said of Podemos’s Complutense core.) He admitted he was tired, and a slightly gaunt look emphasised the sense of asceticism.

Iglesias is aware of the paradox of a party with anti-capitalist roots bidding to administer a market-based economy. “In the short term we are limited to using the state to redistribute a little more, have fairer taxes, boost the economy and start building a model that recovers industry and brings back sovereignty. We accept that the euro is inescapable. The change we represent is, in some way, about recovering a consensus that 20 years ago would even have included some parts of Christian democracy.” Among other measures, he would stimulate the economy by redistributing money to the poor and boosting the public payroll, adding more tax inspectors, judges and social-service workers, and paying for this with higher taxes.

An Iglesias government would take some lessons from Syriza. He did not see the deal that Syriza made in February, which gave Greece a four-month extension on its bailout, as a climb-down by his friend Tsipras. “A small, weak country that is much less important to the eurozone and the EU than Spain, has changed the way things are done – by adopting a tough, stony-faced stance,” he said. In negotiations, Iglesias would use Spain’s muscle as the eurozone’s fourth-largest economy (which, implicitly, makes it big enough to bring the currency down). “You can’t get everything you want, but if you start out hard-faced and tough, then the results are completely different.”

Iglesias likes to deflect questions about populism by pointing to Rajoy’s 2011 electoral pledge to create 3.5m jobs, when the economy has actually shed 600,000 since then. “The real populists are those who make impossible promises,” he said. But the party ties itself in knots over the description. Errejón told me opponents were both right and wrong to call them populists. “The establishment uses populism as a synonym for telling the impoverished majority what it wants to hear,” he said. “That takes us straight back to the idea that only the better-off should vote. It is as if the masses were childlike.” Iglesias sidestepped the issue with a flash of intellectual arrogance. “Laclau would never use the concept of populism in the way that readers of the Guardian would understand it,” he said, denying that there was any demagoguery in Podemos and adding that, to Laclau, most politics was populism anyway.

His bid for greater sovereignty for Spaniards includes a wider separation ofEurope from the US, which he feels dictated EU policy over Ukraine. “I don’t feel any ideological sympathy for Putin, but I think the EU was wrong to take such a belligerent stance with Russia,” he said. Referring to the Maidan protests that eventually led to the revolution, he said: “It was unreasonable to back what – to use a softer expression than coup d’etat – was an illegal displacement of political power.”

Iglesias saw no conflict between Podemos’s values and presenting a programme on what many see as a propaganda channel for Iran’s repressive theocracy. “In Fort Apache, I have complete control over style and content,” he said. Were he prime minister, Iglesias would happily keep presenting shows and conducting interviews with actors, film directors, intellectuals and politicians. “It would be a way of showing that you can devote yourself to politics without stopping doing other things,” he said. “I don’t know whether it would be possible in practice. The diary of a prime minister brings limitations, but we are here to change things.”

One journalist wrote that Iglesias is selling a religious tale similar to that of Jesus expelling the money-changers

Regional elections on 24 May will show whether Podemos has peaked. In recent months, Ciudadanos, a new centre-right rival, has transformed the political landscape once again. With its pledge to oust the establishment and usher in a new era of transparent, corruption-free politics, Ciudadanos offers a safe alternative to those scared of Podemos. It even has, in Albert Rivera, a young and charismatic – but far more orthodox – leader to rival Iglesias. A resurgent Spanish economy, now growing and creating jobs much faster than most of Europe, may boost Rajoy at the general election or, at least, hand a semi-healed economy to whoever succeeds him. Press scrutiny, which has shone light on the close links between some senior Podemos people and Venezuela, also hurt their brand just before March 22 elections for the parliament of the strongly socialist southern region of Andalucia, where they nevertheless doubled their vote (from European elections) to 15%.

But the Podemos earthquake has already shattered the status quo, forcing the PSOE into electing a young new leader – Pedro Sánchez – while IU disintegrates into bitter infighting over whether to ally with the party that may prove its nemesis. El País’s pollster narrowly makes Podemos Spain’s most popular party, but the party cannot enter government without seeking coalition allies among the “old” parties it damns as part of “la casta”. That may force it into opposition. “Hopefully Podemos would be willing to work with us,” former PSOE minister Juan Fernando López Aguilar told me in Brussels in December. “But so far, I perceive a threatening mix of arrogance, self-infatuation and condescension.”

It is tempting to see Podemos as a well-planned operation by a group of talented academics, following a populist script written by a line of radical thinkers, but that would be too simple. It is really the result of an open-ended effort by unorthodox idealists to effect change, combining youthful conviction with a desire to test out their ideas in the real world. As it attempts to forge a new consensus, however, it is inevitably drifting away from its radical roots. At a class Iglesias gave to visiting students at the European parliament in December – perhaps his last for a long time – he recognised that if he governs by Europe’s current capitalist rules, leftwing critics will accuse him of being a cowardly reformist. “The answer to that is: ‘And where are your arms for getting rid of capitalism?’” he said. Realism, then, as much as idealism, will dictate Podemos’s future. Only when put into practice will we discover how, or if, the Podemos participative “method” changes democracy, European politics or ordinary lives. But what is certain is that Iglesias has proved the point he liked to make to his students: the powerful really can be challenged.