Owen Jones in The Guardian

Unless there is a dramatic and unlikely political upset, Jeremy Corbyn will again win the Labour leadership contest. It will be a victory gifted by his opponents. Last year, his triumph was dismissed as a combination of madness, petulance and zealotry. But many commentators lack any understanding or curiosity about political movements outside their comfort zone. Political analysts who scramble over one another to understand, say, the rise of Ukip have precious little interest in a similar treatment of Corbynism, abandoning scholarship for sneers. The likes of Ukip or Donald Trump or the French Front National are understood as manifestations, however unfortunate, of genuine grievances: the movements behind Bernie Sanders, Podemos and Jeremy Corbyn are dismissed as armies of the self-indulgent and the deluded.

A few days ago, I wrote a piece about the Labour leadership’s desperate need to get a handle on strategy, vision and competence, and reach beyond its comfort zone. A failure to do so could mean not just its own eventual demise, but that of Labour and the left for a generation or more. Among some, this piece provoked dismay and even fury. Yet Corbyn’s victory is all but assured, and if the left wishes to govern and transform the country as well as a political party, these are questions that have to be addressed – and a leadership contest that may be swiftly followed by a potentially disastrous snap election is exactly the right time. But that is of limited comfort to Corbyn’s opponents – some of whom are now dragging their own party’s membership through the courts. They often seem incapable of soul-searching or reflection.

Corbyn originally stood not to become leader, but to shift the terms of debate. His leadership campaign believed it was charging at a door made of reinforced steel. It turned out to be made of paper. Corbyn’s rise was facilitated by the abolition of Labour’s electoral college and the introduction of a registered supporters scheme. The biggest cheerleaders included Blairites; much of the left was opposed, regarding it – quite legitimately – as an attempt to dilute Labour’s trade union link. When the reform package was introduced, Tony Blair called it “bold and strong”, adding that he probably “should have done it when I was leader”. Two years ago, arch-Blairite columnist John Rentoul applauded the reforms, believing they helped guarantee Ed Miliband would be succeeded by a Blairite. Whoops.

Here was a semi-open primary in which candidates had an opportunity to enthuse the wider public: Corbyn’s opponents failed to do so. The French Socialists managed to attract 2.5 million people to select their presidential candidate in 2011; a similar number voted in the Italian Democratic party’s primary in 2013. In the early stages of last year’s leadership contest, members of Liz Kendall’s team were briefing that she could end up with a million votes. The hubris. The candidates preaching electability had the least traction with a wider electorate. There are many decent Labour MPs, but it is difficult to think of any with the stature of the party’s past giants: Barbara Castle, Nye Bevan, Ernie Bevin, Herbert Morrison, Margaret Bondfield, Harold Wilson, Stafford Cripps, Ellen Wilkinson. Machine politics hollowed out the party, and at great long-term cost. If, last year, there had been a Labour leadership candidate with a clear shot at winning a general election, Labour members might have compromised on their beliefs: there wasn’t, and so they didn’t.

When a political party faces a catastrophic election defeat, a protracted period of reflection and self-criticism is normally expected. Why were we rejected, and how do we win people back? But in Labour’s internal battle, there has been precious little soul-searching by the defeated. Mirroring those on the left who blame media brainwashing for the Tories’ electoral victories, they simply believe they have been invaded by hordes of far-left zombies assembled by Momentum. The membership are reduced to, at best, petulant children; at worst, sinister hate-filled mobs. Some of those now mustering outrage at Corbynistas for smearing Labour critics as Tories were the same people who applied “Trot” as a blanket term for leftwingers in the Blair era. Although Tom Watson (no Blairite) accepts there are Momentum members “deeply interested in political change”, he has raised the spectre of the shrivelled remnants of British Trotskyism manipulating younger members; but surely he accepts they have agency and are capable of thinking for themselves? Arch critics reduce Corbynism to a personality cult, which is wrong. In any case, when Blair was leader, I recall his staunchest devotees behaving like boy-band groupies. I remember Blair’s final speech to party conference – delegates produced supposedly homemade placards declaring“TB 4 eva” and “We love you Tony”.

Corbynism is assailed for having an authoritarian grip on the party, mostly because it wins victories through internal elections and court judgments: ironic, given that Blairism used to be a byword for “control freakery”. Corbyn’s harshest critics claimed superior political nous, judgment and strategy, then launched a disastrously incompetent coup in the midst of a post-Brexit national crisis, deflecting attention from the Tories, sending Labour’s polling position hurtling from poor to calamitous, and provoking almost all-out war between Labour’s membership and the parliamentary party: all for the sake of possibly gifting their enemy an even greater personal mandate. They denounce Corbyn’s foreign associations, but have little to say about former leader Blair literally having been in the pay of Kazakhstan’s dictator Nursultan Nazarbayev, whose regime stands accused of torture and the killing of opponents. Corbyn’s bitterest enemies preach the need to win over middle-class voters, then sneer at Corbynistas for being too middle class (even though, as a point of fact, polling last year found that Corbyn’s voters were the least middle class). They dismiss Corbynistas as entryists lacking loyalty to the Labour party, then leak plans to the Telegraph – the Tories’ in-house paper – to split the party.

It is the absence of any compelling vision that, above all else, created the vacuum Corbyn filled. Despite New Labour’s many limitations and failings, in its heyday it offered something: a minimum wage, a windfall tax on privatised utilities, LGBT rights, tax credits, devolution, public investment. What do Corbyn’s staunchest opponents within Labour actually stand for? Vision was abandoned in favour of finger-wagging about electability with no evidence to back it up. Owen Smith offers no shortage of policies: but it is last summer’s political insurgency within Labour’s ranks one must thank for putting them on the agenda. Some MPs now back him not because they believe in these policies – they certainly do not, and follow Blair’s line that he would prefer a party on a clearly leftwing programme to lose – but because they believe he is a stop-gap.

Anything other than gratitude for New Labour’s record is regarded as unforgivable self-indulgence. The Iraq war – which took the lives of countless civilians and soldiers, plunged the region into chaos and helped spawn Islamic State – is regarded as a freakish, irrational, leftwing obsession. The left defended New Labour against the monstrously untruthful charge that overspending caused the crash, but the failure to properly regulate the banks (yes, the Tories wanted even less regulation) certainly made it far worse, with dire consequences. On these, two of the biggest judgment calls of our time, the left was right and still seethes with resentment that it wasn’t listened to.

The problems go much deeper, of course. Social democracy is in crisis across Europe: there are many factors responsible, from the changing nature of the modern workforce to the current model of globalisation, to the financial crash, to its support for cuts and privatisation. Still, that is no excuse for a failure to reflect. Corbyn’s opponents have long lacked a compelling vision, a significant support base and a strategy to win. When Labour fails at the ballot box, its cheerleaders are often accused of blaming their opponents rather than examining their own failures.

The same accusation can be levelled now at Corbyn’s opponents. They are, by turns, bewildered, infuriated, aghast, miserable about the rise of Corbynism. But they should take ownership of it, because it is their creation. Unless they reflect on their own failures – rather than spit fury at the success of others – they have no future. Deep down, they know it themselves.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Podemos. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Podemos. Show all posts

Thursday, 11 August 2016

Thursday, 4 February 2016

First Corbyn, now Sanders: how young voters' despair is fuelling movements on the left

Owen Jones in The Guardian

On both sides of the Atlantic, economic insecurity is fuelling the rise of new movements on the left.

Bernie Sanders was neck and neck with Hillary Clinton in this week’s Iowa caucus. Photograph: Yin Bogu/Xinhua Press/Corbis

He’s the septuagenarian powered by youth. The figures behind Bernie Sanders’ triumph in Iowa – in which his grassroots insurgency scored a virtual tie against what he rightly described as “the most powerful political organisation” in the US – are astonishing. Among Iowa Democrats aged between 17 and 29, 84% opted for this unlikely youth icon; among those aged 30-44, Sanders still had a 21-point lead over Hillary Clinton. It was older Americans who flocked to Clinton’s camp: nearly seven out of 10 of those aged over 65. The generations appeared separated by a political chasm.

Here is a phenomenon far from specific to the United States. It is a story of young people facing a present and future defined by economic security, often apparently doomed to a worse lot in life than their parents. They often feel unrepresented, ignored, betrayed or outright attacked by the political elite. They are far more progressive on social issues than their grandparents’ generation. And they are helping to drive movements from Sanders’ to Podemos in Spain, from Syriza to Jeremy Corbyn.

That’s not to exaggerate or oversimplify. A “generation” is itself a sweeping generalisation: it may include the retired white billionaire and the black pensioner shivering in a cold home, or the daughter of a miner and the privately educated young man whose rich parents pay his mortgage deposit. Only a minority of young people are meaningfully politically engaged, let alone politically active, and that includes those who opt for conservative or even far-right parties.

But there’s no question that a swath of disenfranchised youth is powering the new movements of the left. Political attitudes have changed. Labour’s rout last May is often compared to the party’s 1983 disaster; but when Labour was defeated under Michael Foot, the Tories had a nine-point lead among 18- to 24-year-olds, while in 2015, Labour achieved a 16-point lead among 18- to 24-year-olds. What’s more, younger Britons were twice as likely to opt for the leftwing Greens as the rest of the population. While a poll last month found that a derisory 16% of those over the age of 60 think Jeremy Corbyn is doing well, the figure rises to 41% among 18- to 24-year-olds. During the leadership contest that swept Corbyn to power, it’s reported that an influx of relatively young members drove the party’s average age down from 53 to 42.

He’s the septuagenarian powered by youth. The figures behind Bernie Sanders’ triumph in Iowa – in which his grassroots insurgency scored a virtual tie against what he rightly described as “the most powerful political organisation” in the US – are astonishing. Among Iowa Democrats aged between 17 and 29, 84% opted for this unlikely youth icon; among those aged 30-44, Sanders still had a 21-point lead over Hillary Clinton. It was older Americans who flocked to Clinton’s camp: nearly seven out of 10 of those aged over 65. The generations appeared separated by a political chasm.

Here is a phenomenon far from specific to the United States. It is a story of young people facing a present and future defined by economic security, often apparently doomed to a worse lot in life than their parents. They often feel unrepresented, ignored, betrayed or outright attacked by the political elite. They are far more progressive on social issues than their grandparents’ generation. And they are helping to drive movements from Sanders’ to Podemos in Spain, from Syriza to Jeremy Corbyn.

That’s not to exaggerate or oversimplify. A “generation” is itself a sweeping generalisation: it may include the retired white billionaire and the black pensioner shivering in a cold home, or the daughter of a miner and the privately educated young man whose rich parents pay his mortgage deposit. Only a minority of young people are meaningfully politically engaged, let alone politically active, and that includes those who opt for conservative or even far-right parties.

But there’s no question that a swath of disenfranchised youth is powering the new movements of the left. Political attitudes have changed. Labour’s rout last May is often compared to the party’s 1983 disaster; but when Labour was defeated under Michael Foot, the Tories had a nine-point lead among 18- to 24-year-olds, while in 2015, Labour achieved a 16-point lead among 18- to 24-year-olds. What’s more, younger Britons were twice as likely to opt for the leftwing Greens as the rest of the population. While a poll last month found that a derisory 16% of those over the age of 60 think Jeremy Corbyn is doing well, the figure rises to 41% among 18- to 24-year-olds. During the leadership contest that swept Corbyn to power, it’s reported that an influx of relatively young members drove the party’s average age down from 53 to 42.

Is it all just youthful naivete? “In 1984 and 1988,” notes the US journalist Peter Beinart, “young voters backed Ronald Reagan and George HW Bush by large margins,” just as Margaret Thatcher attracted a level of youth support that has eluded David Cameron. The evidence that people become naturally more conservative as they age is not conclusive; indeed, on social issues, older people are often simply keeping the conservative attitudes of their youth. “Change is most often toward increased tolerance rather than increased conservatism,” notes one US study. For older Britons, the left may be associated with the disastrous failure of Soviet totalitarianism and the breakdown of the postwar consensus. For younger Britons, the aftermath of financial collapse and a self-evidently profoundly unequal society may loom larger. It’s the fall of Lehman Brothers, not the Berlin Wall, that may be more significant.

The generations seem to live on different political planets. American youth are far more likely to support immigration than their elders, and to have a positive view of Muslims; and while the over-35s are slightly more likely to believe government does too much, the under-35s are decisively more likely to believe it does too little. Here is a generation that has grown up in a world defined by market failure rather than one shaped by cold war rivalries. As a self-described socialist, Sanders is an exceptionally rare breed of American politician. But it is notable that, while just 15% of Americans over 65 have a positive view of socialism, that rises to 36% among the 18- to 29-year-olds, just three points fewer than those who opt for capitalism.

Yet it is surely economic insecurity that drives today’s young radicalism. A poll last year found that nearly half of so-called “millennial” Americans – those aged 18 to 35 – believed that they faced a “dimmer future than their parents”. Forty million Americans are now saddled with student debt, helping to suppress their living standards and leaving them with less disposable income for, say, a mortgage or a car. Home ownership across the Atlantic – the linchpin of the “American dream” – is now at its lowest level for nearly half a century. The economic recovery is an abstraction for many young Americans, all too often driven into insecure and low-paid occupations with little prospect of rising wages or a standard of living they believe they deserve.

A similar picture could be painted in Britain, of course. Government policies have disproportionately targeted younger people: whether it be the punishing of educational aspiration with the trebling of student fees, the cutting of youth services, the scrapping of the Educational Maintenance Allowance, a minimum wage that discriminates against the young, cuts to youth services or a fall in living standards that older Britons have not had to endure. A young person may find that attending university – which now means accruing a huge pile of debt – does not open doors it once did. Home ownership is at its lowest level for a quarter of a century, and it has particularly plummeted among the young, with evidence that many have given up saving up for a deposit altogether. There are now more private tenants than social tenants, and half of those in an often unregulated private rented sector with what can be income-devouring rents are under 34.

But here is the danger. Like other western nations, Britain is an ageing society, and older voters are both decisively opting for the Conservatives, and turning out to vote in great number. The new movements face a formidable task: to both inspire younger voters to turn out in greater number, and persuade a substantial number of older Britons of their cause. A failure to do so will doom these movements. But the mainstream political elite should not feel complacent. They seem to believe they can abandon the young and face no political consequences. They may find that, one day, they run out of luck.

The generations seem to live on different political planets. American youth are far more likely to support immigration than their elders, and to have a positive view of Muslims; and while the over-35s are slightly more likely to believe government does too much, the under-35s are decisively more likely to believe it does too little. Here is a generation that has grown up in a world defined by market failure rather than one shaped by cold war rivalries. As a self-described socialist, Sanders is an exceptionally rare breed of American politician. But it is notable that, while just 15% of Americans over 65 have a positive view of socialism, that rises to 36% among the 18- to 29-year-olds, just three points fewer than those who opt for capitalism.

Yet it is surely economic insecurity that drives today’s young radicalism. A poll last year found that nearly half of so-called “millennial” Americans – those aged 18 to 35 – believed that they faced a “dimmer future than their parents”. Forty million Americans are now saddled with student debt, helping to suppress their living standards and leaving them with less disposable income for, say, a mortgage or a car. Home ownership across the Atlantic – the linchpin of the “American dream” – is now at its lowest level for nearly half a century. The economic recovery is an abstraction for many young Americans, all too often driven into insecure and low-paid occupations with little prospect of rising wages or a standard of living they believe they deserve.

A similar picture could be painted in Britain, of course. Government policies have disproportionately targeted younger people: whether it be the punishing of educational aspiration with the trebling of student fees, the cutting of youth services, the scrapping of the Educational Maintenance Allowance, a minimum wage that discriminates against the young, cuts to youth services or a fall in living standards that older Britons have not had to endure. A young person may find that attending university – which now means accruing a huge pile of debt – does not open doors it once did. Home ownership is at its lowest level for a quarter of a century, and it has particularly plummeted among the young, with evidence that many have given up saving up for a deposit altogether. There are now more private tenants than social tenants, and half of those in an often unregulated private rented sector with what can be income-devouring rents are under 34.

But here is the danger. Like other western nations, Britain is an ageing society, and older voters are both decisively opting for the Conservatives, and turning out to vote in great number. The new movements face a formidable task: to both inspire younger voters to turn out in greater number, and persuade a substantial number of older Britons of their cause. A failure to do so will doom these movements. But the mainstream political elite should not feel complacent. They seem to believe they can abandon the young and face no political consequences. They may find that, one day, they run out of luck.

Sunday, 20 September 2015

The Guardian's pessimistic take on Corbyn let our readers down

Ed Vulliamy in The Guardian

For many of our readers and potential readers, the Labour leadership result was a singular moment of hope, even euphoria. It was the first time many of our young readers felt anything like relevance to, let alone empowerment within, a political system that has alienated them utterly.

The Observer – a broad church, to which I’m doggedly loyal – responded to Jeremy Corbyn’s landslide with an editorial foreseeing inevitable failure at a general election of the mandate on which he won. For what it’s worth, I felt we let down many readers and others by not embracing at least the spirit of the result, propelled as it was by moral principles of equality, peace and justice. These are no longer tap-room dreams but belong to a mass movement in Britain, as elsewhere in Europe.

It came as a disappointment – as I suspect it did to others who supported Corbyn, or were interested – to find such a consensus ready to pour cold water on the parade. To behold so little curiosity towards, let alone sympathy with, why this happened.

Of course the rest of the media were in on the offensive. Our sister paper the Guardian had endorsed a candidate who lost, humiliated; the Tory press barons performed to script. Here was a chance for the Observer to stand out from the crowd. But instead, we conjoined the chorus with our own – admittedly more progressive – version of this obsession with electoral strategy with little regard to what Corbyn says about the principles of justice, peace and equality (or less inequality). It came across as churlish, I’m sure, to many readers on a rare day of something different.

I accept that we are a reformist paper, and within those parameters one has to get elected. But that should not mean a digging-in by, and with, the parliamentary inside-baseball Labour party whose days and ways of presenting politics like corporate management selling a product (or explaining a product fault) have just been soundly rejected by its membership. Why embed with MPs in a parliament no one trusts against the democratic vote outside it?

And anyway, what if? Who, five years ago, would have predicted Syriza’s victory in Greece or bet on Podemos taking Madrid and Barcelona, now preparing for a role in government? It’s not as though the Observer’s accumulated editorials disagree that much with Corbyn.

During Ed Miliband’s Labour, the Observer robustly questioned the health of capitalism – our columnist Will Hutton calls it “turbo-capitalism”. We urged support for a living wage and the working poor, and the likes of Robert Reich and David Simon have filled our pages with more radical critiques of capitalism than Corbyn’s.

Anyway, how much of what Corbyn argues do most voters disagree with, if they stop to think? Do people approve of bewildering, high tariffs set by the cartel of energy companies, while thousands of elderly people die each winter of cold-related diseases? Do students and parents from middle- and low-income families want tuition fees?

Do people like paying ludicrous fares for signal-failure, delays and overcrowding on inept railways? Do people urge tax evasion by multinationals and billionaires, which they then subsidise with cuts to the NHS? Post-cold war, who exactly are we supposed to kill en masse with these expensive nuclear missiles? What’s so good about the things Corbyn wants to drastically change?

Even more fundamental is the appeal to principle and morality – peace, justice and internationalism – which drove the Labour grassroots vote, and was spoken at the rally for refugees which Corbyn made his first engagement and for which this newspaper stands absolutely. Why not embrace those principles, or at least show an interest in the fact that hundreds of thousands of people just did? Which better reflects the Britain we want: Corbyn’s “open your hearts” or Cameron’s “swarm”?

The parliamentary bubble – and our editorial – calculate that we cannot fundamentally change Britain on the basis of these aspirations, even if many people yearn to. In the acceptance speech, Corbyn should have appealed beyond the party in which he is steeped; perhaps he too inhabits a different echo-chamber.

But this isn’t about Corbyn, it’s about why he’s suddenly there. And what an appalling lesson to draw: someone is overwhelmingly elected to falteringly but seriously challenge that stasis and order of things – by urging peace, justice, republic and equality – only to be evicted by the deep system into a lethal ice-storm the moment he leaves the tent, like Captain Oates, though not of his own volition.

And even if middle England is more adverse to radical politics than middle Spain or Greece, does that mean we have to align with this mainstream stasis, just because it is so? What’s the point of principles if their trade-off for power is a principle in itself? Why have principles at all?

The legal philosopher Costas Douzinas argues for a separation of words: using “politics” to describe horse-trading between parties, which feign differences but actually agree, and “the political” to describe antagonisms that really exist in society. On that basis, why start with the stasis of “politics” to approach “the political”, rather than the reverse: invoke “the political” to challenge the stasis of “politics”? Especially alongside Greece, Spain and elsewhere.

Instead of a stirring leader, which did not have to endorse Corbyn but could celebrate the spirit of the vote along with those who delivered it, we’ve left a lot of good, loyal and decent people who read our newspaper feeling betrayed.

“There’s something happening in here / What it is ain’t exactly clear”, wrote Stephen Stills in 1967. It’s a good description of where we are with all this – we don’t as yet have the map whence this came, where it’s going or even what it is.

Dave Crosby sang: “Don’t try to get yourself elected” (from a mighty number called “Long Time Gone”). Along with almost half this country, I was inclined to agree, but Corbyn’s election throws Crosby’s dictum into question, just as to cut Corbyn down would prove Crosby right. “We can change the world” sang Graham Nash. But are we only allowed to try if middle England, the media and parliament try too?

For many of our readers and potential readers, the Labour leadership result was a singular moment of hope, even euphoria. It was the first time many of our young readers felt anything like relevance to, let alone empowerment within, a political system that has alienated them utterly.

The Observer – a broad church, to which I’m doggedly loyal – responded to Jeremy Corbyn’s landslide with an editorial foreseeing inevitable failure at a general election of the mandate on which he won. For what it’s worth, I felt we let down many readers and others by not embracing at least the spirit of the result, propelled as it was by moral principles of equality, peace and justice. These are no longer tap-room dreams but belong to a mass movement in Britain, as elsewhere in Europe.

It came as a disappointment – as I suspect it did to others who supported Corbyn, or were interested – to find such a consensus ready to pour cold water on the parade. To behold so little curiosity towards, let alone sympathy with, why this happened.

Of course the rest of the media were in on the offensive. Our sister paper the Guardian had endorsed a candidate who lost, humiliated; the Tory press barons performed to script. Here was a chance for the Observer to stand out from the crowd. But instead, we conjoined the chorus with our own – admittedly more progressive – version of this obsession with electoral strategy with little regard to what Corbyn says about the principles of justice, peace and equality (or less inequality). It came across as churlish, I’m sure, to many readers on a rare day of something different.

I accept that we are a reformist paper, and within those parameters one has to get elected. But that should not mean a digging-in by, and with, the parliamentary inside-baseball Labour party whose days and ways of presenting politics like corporate management selling a product (or explaining a product fault) have just been soundly rejected by its membership. Why embed with MPs in a parliament no one trusts against the democratic vote outside it?

And anyway, what if? Who, five years ago, would have predicted Syriza’s victory in Greece or bet on Podemos taking Madrid and Barcelona, now preparing for a role in government? It’s not as though the Observer’s accumulated editorials disagree that much with Corbyn.

During Ed Miliband’s Labour, the Observer robustly questioned the health of capitalism – our columnist Will Hutton calls it “turbo-capitalism”. We urged support for a living wage and the working poor, and the likes of Robert Reich and David Simon have filled our pages with more radical critiques of capitalism than Corbyn’s.

Anyway, how much of what Corbyn argues do most voters disagree with, if they stop to think? Do people approve of bewildering, high tariffs set by the cartel of energy companies, while thousands of elderly people die each winter of cold-related diseases? Do students and parents from middle- and low-income families want tuition fees?

Do people like paying ludicrous fares for signal-failure, delays and overcrowding on inept railways? Do people urge tax evasion by multinationals and billionaires, which they then subsidise with cuts to the NHS? Post-cold war, who exactly are we supposed to kill en masse with these expensive nuclear missiles? What’s so good about the things Corbyn wants to drastically change?

Even more fundamental is the appeal to principle and morality – peace, justice and internationalism – which drove the Labour grassroots vote, and was spoken at the rally for refugees which Corbyn made his first engagement and for which this newspaper stands absolutely. Why not embrace those principles, or at least show an interest in the fact that hundreds of thousands of people just did? Which better reflects the Britain we want: Corbyn’s “open your hearts” or Cameron’s “swarm”?

The parliamentary bubble – and our editorial – calculate that we cannot fundamentally change Britain on the basis of these aspirations, even if many people yearn to. In the acceptance speech, Corbyn should have appealed beyond the party in which he is steeped; perhaps he too inhabits a different echo-chamber.

But this isn’t about Corbyn, it’s about why he’s suddenly there. And what an appalling lesson to draw: someone is overwhelmingly elected to falteringly but seriously challenge that stasis and order of things – by urging peace, justice, republic and equality – only to be evicted by the deep system into a lethal ice-storm the moment he leaves the tent, like Captain Oates, though not of his own volition.

And even if middle England is more adverse to radical politics than middle Spain or Greece, does that mean we have to align with this mainstream stasis, just because it is so? What’s the point of principles if their trade-off for power is a principle in itself? Why have principles at all?

The legal philosopher Costas Douzinas argues for a separation of words: using “politics” to describe horse-trading between parties, which feign differences but actually agree, and “the political” to describe antagonisms that really exist in society. On that basis, why start with the stasis of “politics” to approach “the political”, rather than the reverse: invoke “the political” to challenge the stasis of “politics”? Especially alongside Greece, Spain and elsewhere.

Instead of a stirring leader, which did not have to endorse Corbyn but could celebrate the spirit of the vote along with those who delivered it, we’ve left a lot of good, loyal and decent people who read our newspaper feeling betrayed.

“There’s something happening in here / What it is ain’t exactly clear”, wrote Stephen Stills in 1967. It’s a good description of where we are with all this – we don’t as yet have the map whence this came, where it’s going or even what it is.

Dave Crosby sang: “Don’t try to get yourself elected” (from a mighty number called “Long Time Gone”). Along with almost half this country, I was inclined to agree, but Corbyn’s election throws Crosby’s dictum into question, just as to cut Corbyn down would prove Crosby right. “We can change the world” sang Graham Nash. But are we only allowed to try if middle England, the media and parliament try too?

Saturday, 20 June 2015

Greek debt crisis is the Iraq War of finance

Guardians of financial stability are deliberately provoking a bank run and endangering Europe's system in their zeal to force Greece to its knees.

By Ambrose Evans-Pritchard in The Telegraph 6:29PM BST 19 Jun 2015

Rarely in modern times have we witnessed such a display of petulance and bad judgment by those supposed to be in charge of global financial stability, and by those who set the tone for the Western world.

The spectacle is astonishing. The European Central Bank, the EMU bail-out fund, and the International Monetary Fund, among others, are lashing out in fury against an elected government that refuses to do what it is told. They entirely duck their own responsibility for five years of policy blunders that have led to this impasse.

They want to see these rebel Klephts hanged from the columns of the Parthenon – or impaled as Ottoman forces preferred, deeming them bandits - even if they degrade their own institutions in the process.

If we want to date the moment when the Atlantic liberal order lost its authority – and when the European Project ceased to be a motivating historic force – this may well be it. In a sense, the Greek crisis is the financial equivalent of the Iraq War, totemic for the Left, and for Souverainistes on the Right, and replete with its own “sexed up” dossiers.

Does anybody dispute that the ECB – via the Bank of Greece - is actively inciting a bank run in a country where it is also the banking regulator by issuing this report on Wednesday?

It warned of an "uncontrollable crisis" if there is no creditor deal, followed by soaring inflation, "an exponential rise in unemployment", and a "collapse of all that the Greek economy has achieved over the years of its EU, and especially its euro area, membership".

The guardian of financial stability is consciously and deliberately accelerating a financial crisis in an EMU member state - with possible risks of pan-EMU and broader global contagion – as a negotiating tactic to force Greece to the table.

It did so days after premier Alexis Tsipras accused the creditors of "laying traps" in the negotiations and acting with a political motive. He more or less accused them of trying to destroy an elected government and bring about regime change by financial coercion.

I leave it to lawyers to decide whether this report is a prima facie violation of the ECB’s primary duty under the EU treaties. It is certainly unusual. The ECB has just had to increase emergency liquidity to the Greek banks by €1.8bn (enough to last to Monday night) to offset the damage from rising deposit flight.

In its report, the Bank of Greece claimed that failure to meet creditor demands would “most likely” lead to the country’s ejection from the European Union. Let us be clear about the meaning of this. It is not the expression of an opinion. It is tantamount to a threat by the ECB to throw the Greeks out of the EU if they resist.

This is not the first time that the ECB has strayed far from its mandate. It forced the Irish state to make good the claims of junior bondholders of Anglo-Irish Bank, saddling Irish taxpayers with extra debt equal to 20pc of GDP.

This was done purely in order to save the European banking system at a time when the ECB was refusing to do the job itself, betraying the primary task of a central bank to act as a lender of last resort.

It sent secret letters to the elected leaders of Spain and Italy in August 2011 demanding detailed changes to internal laws for which it had no mandate or technical competence, even meddling in neuralgic issues of labour law that had previously led to the assassination of two Italian officials by the Red Brigades. It demanded changes to the Spanish constitution.

When Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi balked, the ECB switched off bond purchases, driving 10-year yields to 7.5pc. He was forced from office in a back-room coup d’etat, albeit one legitimised by the ageing ex-Stalinist EU fanatic who then happened to be president of Italy.

Lest we forget, it parachuted in its vice-president – Lucas Papademos – to take over Greece when premier George Papandreou merely suggested that he might submit the EMU bail-out package to a referendum, a wise idea in retrospect. That makes two coups d’etat. Now Syriza fears they are angling for a third.

The creditor power structure has lost its way. The IMF is in confusion. It is enforcing a contractionary austerity policy in Greece – with no debt relief, exchange cushion, or offsetting investment - that has been discredited by its own elite research department as scientifically unsound.

The Fund’s culpability in this fiasco is by now well known. As I argued last week, its own internal documents show that the original bail-out in 2010 was designed to rescue the EMU banking system and monetary union at a time when it had no defences against contagion. Greece was sacrificed.

One should have thought that the IMF would wish to lower the political temperature, given that its own credibility and long-term survival are at stake. But no, Christine Lagarde has upped the political ante by stating that Greece will fall into arrears immediately if it misses a €1.6bn payment to the Fund on June 30.

In my view, this is a discretionary escalation. The normal procedure is to notify the IMF Board after 30 days. This period is a de facto grace period, and in a number of past cases the arrears were cleared up quietly during the interval before the matter ever reached the Board.

The IMF could have let this process run in the case of Greece. It has chosen not to do so, ostensibly on the grounds that the sums are unusually large.

Klaus Regling, head of the eurozone bail-out fund (EFSF), entered on cue to hint strongly that his organisation would trigger cross-default clauses on its Greek bonds – 45pc of the Greek package – even though there is no necessary reason why it should do so. It is an optional matter for the EFSF board.

He seems to be threatening an EFSF default, even though the Greeks themselves are not doing so, a remarkable state of affairs.

It is obvious what is happening. The creditors are acting in concert. Instead of stopping to reflect for one moment on the deeper wisdom of their strategy, they are doubling down mechanically, appearing to assume that terror tactics will cow the Greeks at the twelfth hour.

Personally, I am a Burkean conservative with free market views. Ideologically, Syriza is not my cup tea. Yet we Burkeans do like democracy – and we don’t care for monetary juntas – even if it leads to the election of a radical-Left government.

As it happens, Edmund Burke would have found the plans presented to the Eurogroup last night by finance minister Yanis Varoufakis to be rational, reasonable, fair, and proportionate.

They include a debt swap with ECB bonds coming due in July and August exchanged for bonds from the bail-out fund. They would have longer maturities and lower interest rates, reflecting the market borrowing cost of the creditors.

Syriza said from the outset that it was eager to work on market reforms with the OECD, the leading authority. It wants to team up with the International Labour Organisation on Scandinavian style flexi-security and labour reforms, a valid alternative to the German-style Hartz IV reforms that have impoverished the bottom fifth of German society and which no Left-wing movement can stomach.

It wished to push through a more radical overhaul of the Greek state that anything yet done under five years of Troika rule – and much has been done, to be fair.

As Mr Varoufakis told Die Zeit: “Why does a kilometer of freeway cost three times as much where we are as it does in Germany? Because we’re dealing with a system of cronyism and corruption. That’s what we have to tackle. But, instead, we’re debating pharmacy opening times."

The Troika pushed privatisation of profitable state assets at knock-down depression prices to private monopolies, to the benefit of an entrenched elite. To call that reforms invites a bitter cynicism.

The only reason that the Troika pushed this policy was in order to extract money. It was acting at a debt collector. “The reforms were a smokescreen. Whenever I tried talking about proposals, they were bored. I could see it in their body language," Mr Varoufakis told me.

The truth is that the creditor power structure never even looked at the Greek proposals. They never entertained the possibility of tearing up their own stale, discredited, legalistic, fatuous Troika script.

The decision was made from the outset to demand strict enforcement of the terms agreed in the original Memorandum, which even the last conservative pro-Troika government was unable to implement - regardless of whether it makes any sense, or actually increases the chance that Germany and other lenders will recoup their money.

At best, it is bureaucratic inertia, a prime exhibit of why the EU has become unworkable, almost genetically incapable of recognising and correcting its own errors.

At worst, it is nasty, bullying, insistence on ritual capitulation for the sake of it.

We all know the argument. The EU is worried about political “moral hazard”, about what Podemos might achieve in Spain, or the eurosceptics in Italy, or the Front National in France, if Syriza is seen to buck the system and get away with it.

But do the proponents of this establishment view – and one hears it a lot – really think that Podemos can be defeated by crushing Syriza, or that they can discourage Marine Le Pen by violating the sovereignty and sensibilities of a nation?

Do they think that the EU’s ever-declining hold on the loyalty of Europe’s youth can be reversed by creating a martyr state on the Left? Do they not realize that this is their own Guatemala, the radical experiment of Jacobo Arbenz that was extinguished by the CIA in 1954, only to set off the Cuban revolution and thirty years of guerrilla warfare across Latin America? Don’t these lawyers – and yes they are almost all lawyers - ever look beyond their noses?

The Versailles victors assumed reflexively that they had the full weight of moral authority on their side when they imposed their Carthiginian settlement on a defeated Germany in 1919 and demanded the payment of debts that they themselves invented. History judged otherwise.

Thursday, 2 April 2015

Greek defiance mounts as Alexis Tsipras turns to Russia and China

Ambrose Evans Pritchard in The Telegraph

Two months of EU bluster and reproof have failed to cow Greece. It is becoming clear that Europe’s creditor powers have misjudged the nature of the Greek crisis and can no longer avoid facing the Morton’s Fork in front of them.

Any deal that goes far enough to assuage Greece’s justly-aggrieved people must automatically blow apart the austerity settlement already fraying in the rest of southern Europe. The necessary concessions would embolden populist defiance in Spain, Portugal and Italy, and bring German euroscepticism to the boil.

Emotional consent for monetary union is ebbing dangerously in Bavaria and most of eastern Germany, even if formulaic surveys do not fully catch the strength of the undercurrents.

This week's resignation of Bavarian MP Peter Gauweiler over Greece’s bail-out extension can, of course, be over-played. He has long been a foe of EMU. But his protest is unquestionably a warning shot for Angela Merkel's political family.

Mr Gauweiler was made vice-chairman of Bavaria's Social Christians (CSU) in 2013 for the express purpose of shoring up the party's eurosceptic wing and heading off threats from the anti-euro Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD).

Yet if the EMU powers persist mechanically with their stale demands - even reverting to terms that the previous pro-EMU government in Athens rejected in December - they risk setting off a political chain-reaction that can only eviscerate the EU Project as a motivating ideology in Europe.

Jean-Claude Juncker, the European Commission’s chief, understands the risk perfectly, warning anybody who will listen that Grexit would lead to an “irreparable loss of global prestige for the whole EU” and crystallize Europe’s final fall from grace.

When Warren Buffett suggests that Europe might emerge stronger after a salutary purge of its weak link in Greece, he confirms his own rule that you should never dabble in matters beyond your ken.

Alexis Tsipras leads the first radical-Leftist government elected in Europe since the Second World War. His Syriza movement is, in a sense, totemic for the European Left, even if sympathisers despair over its chaotic twists and turns. As such, it is a litmus test of whether progressives can pursue anything resembling an autonomous economic policy within EMU.

There are faint echoes of what happened to the elected government of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala, a litmus test for the Latin American Left in its day. His experiment in land reform was famously snuffed out by a CIA coup in 1954, with lasting consequences. It was the moment of epiphany for Che Guevara (below), then working as a volunteer doctor in the country.

A generation of students from Cuba to Argentina drew the conclusion that the US would never let the democratic Left hold power, and therefore that power must be seized by revolutionary force.

We live in gentler times today, yet any decision to eject Greece and its Syriza rebels from the euro by cutting off liquidity to the Greek banking system would amount to the same thing, since the EU authorities do not have a credible justification or a treaty basis for acting in such a way. Rebuking Syriza for lack of “reform” sticks in the craw, given the way the EU-IMF Troika winked at privatisation deals that violated the EU’s own competition rules, and chiefly enriched a politically-connected elite.

Forced Grexit would entrench a pervasive suspicion that EU bodies are ultimately agents of creditor enforcement. It would expose the Project’s post-war creed of solidarity as so much humbug.

Willem Buiter, Citigroup’s chief economist, warns that Greece faces an “economic show of horrors” if it returns to the drachma, but it will not be a pleasant affair for Europe either. “Monetary union is meant to be unbreakable and irrevocable. If it is broken, and if it is revoked, the question will arise over which country is next,” he said.

“People have tried to make Greece into a uniquely eccentric member of the eurozone, accusing them of not doing this or not doing that, but a number of countries share the same weaknesses. You think the Greek economy is far too closed? Welcome to Portugal. You think there is little social capital in Greece, and no trust between the government and citizens? Welcome to southern Europe,” he said.

Greece could not plausibly remain in Nato if ejected from EMU in acrimonious circumstances. It would drift into the Russian orbit, where Hungary’s Viktor Orban already lies. The southeastern flank of Europe’s security system would fall apart.

Rightly or wrongly, Mr Tsipras calculates that the EU powers cannot allow any of this to happen, and therefore that their bluff can be called. “We are seeking an honest compromise, but don't expect an unconditional agreement from us," he told the Greek parliament this week.

If it were not for the fact that a sovereign default on €330bn of debts – bail-out loans and Target2 liabilities within the ECB system – would hurt taxpayers in fellow Club Med states that are also in distress, most Syriza deputies would almost relish the chance to detonate this neutron bomb.

Mr Tsipras is now playing the Russian card with an icy ruthlessness, more or less threatening to veto fresh EU measures against the Kremlin as the old set expires. “We disagree with sanctions. The new European security architecture must include Russia,” he told the TASS news agency.

He offered to turn Greece into a strategic bridge, linking the two Orthodox nations. “Russian-Greek relations have very deep roots in history,” he said, hitting all the right notes before his trip to Moscow next week.

The Kremlin has its own troubles as Russian companies struggle to meet redemptions on $630bn of dollar debt, forcing them to seek help from state’s reserve funds. Russia’s foreign reserves are still $360bn – down from $498bn a year ago – but the disposable sum is far less given a raft of implicit commitments. Even so, President Vladimir Putin must be sorely tempted to take a strategic punt on Greece, given the prize at hand.

Panagiotis Lafazanis, Greece’s energy minister and head of Syriza’s Left Platform, was in Moscow this week meeting Gazprom officials. He voiced a “keen interest” in the Kremlin’s new pipeline plan though Turkey, known as "Turkish Stream".

Operating in parallel, Greece’s deputy premier, Yannis Drakasakis, vowed to throw open the Port of Piraeus to China’s shipping group Cosco, giving it priority in a joint-venture with the Greek state’s remaining 67pc stake in the ports. On cue, China has bought €100m of Greek T-bills, helping to plug a funding shortfall as the ECB orders Greek banks to step back.

One might righteously protest at what amounts to open blackmail by Mr Tsipras, deeming such conduct to be a primary violation of EU club rules. Yet this is to ignore what has been done to Greece over the past four years, and why the Greek people are so angry.

Leaked IMF minutes from 2010 confirm what Syriza has always argued: the country was already bankrupt and needed debt relief rather than new loans. This was overruled in order to save the euro and to save Europe’s banking system at a time when EMU had no defences against contagion.

Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras and finance minister Yanis Varoufakis

Finance minister Yanis Varoufakis rightly calls it “a cynical transfer of private losses from the banks’ books onto the shoulders of Greece’s most vulnerable citizens”. A small fraction of the €240bn of loans remained in the Greek economy. Some 90pc was rotated back to banks and financial creditors. The damage was compounded by austerity overkill. The economy contracted so violently that the debt-ratio rocketed instead of coming down, defeating the purpose.

India’s member on the IMF board warned that such policies could not work without offsetting monetary stimulus. "Even if, arguably, the programme is successfully implemented, it could trigger a deflationary spiral of falling prices, falling employment and falling fiscal revenues that could eventually undermine the programme itself.” He was right in every detail.

Marc Chandler, from Brown Brothers Harriman, says the liabilities incurred – pushing Greece’s debt to 180pc of GDP - almost fit the definition of “odious debt” under international law. “The Greek people have not been bailed out. The economy has contracted by a quarter. With deflation, nominal growth has collapsed and continues to contract,” he said.

The Greeks know this. They have been living it for five years, victims of the worst slump endured by any industrial state in 80 years, and worse than European states in the Great Depression. The EMU creditors have yet to acknowledge in any way that Greece was sacrificed to save monetary union in the white heat of the crisis, and therefore that it merits a special duty of care. Once you start to see events through Greek eyes – rather than through the eyes of the north European media and the Brussels press corps - the drama takes on a different character.

It is this clash of two entirely different and conflicting narratives that makes the crisis so intractable. Mr Tsipras told his own inner circle privately before his election in January that if pushed to the wall by the EMU creditor powers, he would tell them “to do their worst”, bringing the whole temple crashing down on their heads. Everything he has done since suggests that he may just mean it.

Tuesday, 31 March 2015

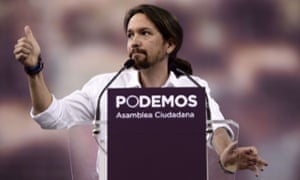

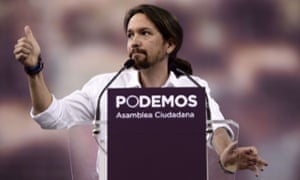

The Podemos revolution: how a small group of radical academics changed European politics

At the start of the 2008 academic year, Pablo Iglesias, a 29-year-old lecturer with a pierced eyebrow and a ponytail greeted his students at the political sciences faculty of the Complutense University in Madrid by inviting them to stand on their chairs. The idea was to re-enact a scene from the film Dead Poets Society. Iglesias’s message was simple. His students were there to study power, and the powerful can be challenged. This stunt was typical of him. Politics, Iglesias thought, was not just something to be studied. It was something you either did, or let others do to you. As a professor, he was smart, hyperactive and – as a founder of a university organisation called Counter-Power – quick to back student protest. He did not fit the classic profile of a doctrinaire intellectual from Spain’s communist-led left. But he was clear about what was to blame for the world’s ills: the unfettered, globalised capitalism that, in the wake of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, had installed itself as the developed world’s dominant ideology.

Iglesias and the students, ex-students and faculty academics worked hard to spread their ideas. They produced political television shows and collaborated with their Latin American heroes – left-leaning populist leaders such as Rafael Correa of Ecuador or Evo Morales of Bolivia. But when they launched their own political party on 17 January 2014 and gave it the name Podemos (“We Can”), many dismissed it. With no money, no structure and few concrete policies, it looked like just one of several angry, anti-austerity parties destined to fade away within months.

A year later, on 31 January 2015, Iglesias strode across a stage in Madrid’s emblematic central square, the Puerta del Sol. It was filled with 150,000 people, squeezed in so tightly that it was impossible to move. He addressed the crowd with the impassioned rhetoric for which opponents have branded him a dangerous leftwing populist. He railed against the monsters of “financial totalitarianism” who had humiliated them all. He told Podemos’s followers to dream and, like that noble madman Don Quixote, “take their dreams seriously”.Spain was in the grip of historic, convulsive change. The serried crowd were heirs to the common folk who – armed with knives, flowerpots and stones – had rebelled against Napoleonic troops in nearby streets two centuries earlier. “We can dream, we can win!” he shouted.

Polls suggest that he is right. Since 1982, Spain has been governed by only two parties. Yet El País newspaper now places Podemos at 22%, ahead of both the ruling conservative Partido Popular (PP) and its leftwing opposition Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE). If Podemos can grow further, Iglesias could become prime minister after elections that are expected in November. This would be an almost unheard-of achievement for such a young party.

Many in the Puerta del Sol longed to see that day. “Yes we can! Yes we can!” they chanted. Other onlookers shivered, recalling Iglesias’s praise for Venezuela’s late president Hugo Chávez and fearing an eruption of Latin American-style populism in a country gripped by debt, austerity and unemployment. But without Podemos, supporters feared, Spain faced the prospect of becoming like Greece, with its disintegrating welfare state, crumbling middle class and rampant inequality.

On stage that day, Iglesias declared that Podemos would take back power from self-serving elites and hand it over to the people. To do that, the new party needs votes. If that means arousing emotions and being accused of populism, so be it. And, as the party’s founders have already shown, if they have to renounce some of their ideas in order to broaden their appeal, or risk upsetting some in their grassroots movement by tightening central control, they are ready to do that, too. The aim, after all, is to win.

At first glance, Podemos’s dizzying rise looks miraculous. In truth, the project evolved over a long time, though even the organisers did not know it would eventually spawn a party, or that a global financial crisis would provide their opportunity. In Spain today, one-third of the labour force is either jobless or earns less than the minimum annual salary of €9,080. In big cities, the sight of people raiding bins for food or things to sell – a rarity in pre-crisis Spain – is no longer shocking. A fatalistic gloom has settled over a country that rode a wave of optimism for three decades after it transformed itself from dictatorship to democracy. After years of economic growth, the financial crisis burst Spain’s construction bubble. Countless corruption cases – involving both the PP and PSOE – have stoked widespread anger towards the established political class. “A political crisis is a moment for daring,” Iglesias told an audience recently. “It is when a revolutionary is capable of looking people in the eye and telling them, ‘Look, those people are your enemies.’”

He is not the first Pablo Iglesias to shake Spain’s political order. He is named after the man who founded the PSOE in 1879. (His parents first met at a remembrance ceremony in front of Iglesias’s tomb.) As a teenager, Iglesias was a member of the Communist Youth in Vallecas, one of Madrid’s poorest and proudest barrios. He still lives there today, in a modest apartment on a graffiti-daubed 1980s estate of medium- and high-rise blocks. (“Defend your happiness, organise your rage,” reads one graffiti slogan.) Even as a teenager, he was “a leader and great seducer”, recalled a senior Podemos member who had attended the same youth group. Iglesias studied law at the Complutense University before taking a second undergraduate degree in political science. He went on to write a PhD thesis on disobedience and anti-globalisation protests that was awarded a prestigious cum laude grade

.

Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias rails against the monsters of ‘financial totalitarianism’, and tells the party’s followers to ‘take their dreams seriously’. Photograph: Dani Pozo/AFP/Getty

It was at Complutense, where he began to lecture after receiving his doctorate, that Iglesias met the key figures who would help him found Podemos. Deeply influenced by Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist thinker who argued that a key battle was over the machinery that shaped public opinion, this group also found inspiration at the University of Essex. There, the Argentine academic Ernesto Laclau began in the 1970s to write a series of works on Marxism, populism and demoracy which, along with work by his Belgian wife Chantal Mouffe (now at the University of Westminister), have had a profound impact on Podemos’s leadership. Their complex 1985 book, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, remains a key point of reference for Podemos’s leadership.

Socialism, Laclau and Mouffe argued, should no longer focus on class warfare. Instead, socialists should seek to unite discontented groups – such as feminists, gay people, environmentalists, the unemployed – against a clearly defined enemy, usually the establishment. One way of doing this was through a charismatic leader who would fight the powerful on behalf of the underdogs. Laclau and Mouffe encouraged this new left to appeal to voters with simple, emotionally engaging rhetoric. They argued that liberal elites decry such tactics as populism because they are scared of ordinary people becoming involved in politics.

“There is too much consensus and not enough dissent [in leftwing politics],” said Mouffe, an elegant 71-year-old, at her London apartment in February. To her, the rise of rightwing populists such as Marine Le Pen’s Front National in France or Nigel Farage’s Ukip in the UK is proof that the post-Thatcherite consensus – cemented by “third way” social democrats such as Tony Blair – has left a dangerous vacuum. “The choice today is between rightwing or leftwing populism,” Mouffe told Iglesias in a TV interview in February.

If Iglesias had long seen neoliberals as the enemy and social democrats as sellouts, he eventually came to view the traditional far left as well-meaning fools. They damned television as lowbrow and manipulative, refusing to see that people’s politics were increasingly defined by the media they consumed rather than by loyalty to parties. This was something Spain’s aggressive far-right pundits had grasped in the mid-2000s, setting up television channels that exercised much the same pressure on the PP as Fox News does on the Republicans in the US. Iglesias believed it was time for the left to do something similar.

In May 2010 he organised a faculty debate that limited speakers to turns of 99 seconds. He named the event after the ska anthem One Step Beyond. Iglesias asked Tele-K, a neighbourhood TV channel partly housed in a disused Vallecas garage, to record them. “I was amazed by Pablo’s skills as a presenter, and by the care they had taken in setting it up,” Tele-K director Paco Pérez told me. He was sufficiently impressed to invite Iglesias to produce and present a debate series. Iglesias and his small team of students and activists took the idea seriously, although the station’s audience was tiny. “Pablo would even rehearse – something we’d never seen,” said Pérez. “The amazing thing was that we started to get a big online audience. It became a cult show.” La Tuerka (a play on the Spanish word for nut or screw), an initially earnest round-table debate show, became the seed for Podemos.

* * *

On 15 May 2011, Íñigo Errejón, the man who would become Podemos’s No 2, reached Madrid from Quito, Ecuador. Errejón was days away from presenting a PhD thesis at Complutense University that linked the success of Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, to the ideas of Gramsci, Mouffe and Laclau. Friends suggested that he head straight to the Puerta del Sol, where something extraordinary was happening.

Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias rails against the monsters of ‘financial totalitarianism’, and tells the party’s followers to ‘take their dreams seriously’. Photograph: Dani Pozo/AFP/Getty

It was at Complutense, where he began to lecture after receiving his doctorate, that Iglesias met the key figures who would help him found Podemos. Deeply influenced by Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist thinker who argued that a key battle was over the machinery that shaped public opinion, this group also found inspiration at the University of Essex. There, the Argentine academic Ernesto Laclau began in the 1970s to write a series of works on Marxism, populism and demoracy which, along with work by his Belgian wife Chantal Mouffe (now at the University of Westminister), have had a profound impact on Podemos’s leadership. Their complex 1985 book, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, remains a key point of reference for Podemos’s leadership.

Socialism, Laclau and Mouffe argued, should no longer focus on class warfare. Instead, socialists should seek to unite discontented groups – such as feminists, gay people, environmentalists, the unemployed – against a clearly defined enemy, usually the establishment. One way of doing this was through a charismatic leader who would fight the powerful on behalf of the underdogs. Laclau and Mouffe encouraged this new left to appeal to voters with simple, emotionally engaging rhetoric. They argued that liberal elites decry such tactics as populism because they are scared of ordinary people becoming involved in politics.

“There is too much consensus and not enough dissent [in leftwing politics],” said Mouffe, an elegant 71-year-old, at her London apartment in February. To her, the rise of rightwing populists such as Marine Le Pen’s Front National in France or Nigel Farage’s Ukip in the UK is proof that the post-Thatcherite consensus – cemented by “third way” social democrats such as Tony Blair – has left a dangerous vacuum. “The choice today is between rightwing or leftwing populism,” Mouffe told Iglesias in a TV interview in February.

If Iglesias had long seen neoliberals as the enemy and social democrats as sellouts, he eventually came to view the traditional far left as well-meaning fools. They damned television as lowbrow and manipulative, refusing to see that people’s politics were increasingly defined by the media they consumed rather than by loyalty to parties. This was something Spain’s aggressive far-right pundits had grasped in the mid-2000s, setting up television channels that exercised much the same pressure on the PP as Fox News does on the Republicans in the US. Iglesias believed it was time for the left to do something similar.

In May 2010 he organised a faculty debate that limited speakers to turns of 99 seconds. He named the event after the ska anthem One Step Beyond. Iglesias asked Tele-K, a neighbourhood TV channel partly housed in a disused Vallecas garage, to record them. “I was amazed by Pablo’s skills as a presenter, and by the care they had taken in setting it up,” Tele-K director Paco Pérez told me. He was sufficiently impressed to invite Iglesias to produce and present a debate series. Iglesias and his small team of students and activists took the idea seriously, although the station’s audience was tiny. “Pablo would even rehearse – something we’d never seen,” said Pérez. “The amazing thing was that we started to get a big online audience. It became a cult show.” La Tuerka (a play on the Spanish word for nut or screw), an initially earnest round-table debate show, became the seed for Podemos.

* * *

On 15 May 2011, Íñigo Errejón, the man who would become Podemos’s No 2, reached Madrid from Quito, Ecuador. Errejón was days away from presenting a PhD thesis at Complutense University that linked the success of Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, to the ideas of Gramsci, Mouffe and Laclau. Friends suggested that he head straight to the Puerta del Sol, where something extraordinary was happening.

Demonstrators gather near Madrid’s Puerta del Sol for a ‘March for Change’ organised by Podemos in January. Photograph: Gerard Julien/AFP/Getty

Somehow a protest march had turned into a camp that eventually drew tens of thousands of protesters. The indignados, who would inspire the Occupy movement, then took over city squares across the country, railing against politicians. “They don’t represent us!” became the rallying cry. Polls showed that 80% of the public backed the protestors. Some even carried Spain’s red-and-gold flag, a sign that this was bigger than the standard leftwing protests at which the purple, gold and red flag of Spain’s long-lost Republic usually dominated. The indignados debated at open-air assemblies, taking turns to speak and using hand gestures – raised waving hands for “yes”, crossed arms for “no” – to express agreement or disagreement.

For Iglesias and his fellow theorists at Complutense University, the protests made perfect sense. The consensus between Spain’s two biggest parties around German-imposed austerity had turned many citizens into political orphans, with no one to represent them. “Those with the power still governed, but they no longer convinced people,” Errejón told me recently.

Still, a month after the protests began, the squares had emptied. Six months later, at the end of 2011, Spain elected a new government, amid warnings that, whoever won, German chancellor Angela Merkel would be in charge. Disillusioned voters saw that even the PSOE offered little more than cowed obedience to Merkel’s demands for more austerity. Following a low turnout, Mariano Rajoy’s PP won an absolute majority and introduced further cuts while slowly taming budget deficits that had topped 11%. The indignado spirit, it seemed, had been crushed.

In fact, indignado assemblies continued to meet, and for the most politically active, La Tuerka became essential viewing. With time, the show moved to the online news site Público, and became more polished. Each show would begin with Iglesias or his fellow Complutense professor Juan Carlos Monedero delivering a monologue, followed by debate and rap music. When Iran’s state-run Spanish-language television service, HispanTV, asked for an Iglesias-presented show, starting in January 2013, the team jumped at it. The show, called Fort Apache, opened with Iglesias astride a Harley Davidson Sportster motorbike, placing a helmet over his head and – after a close-up of his eyes – slinging a massive crossbow across his back before roaring off. “Watch your head, white man. This is Fort Apache!” he warned in the trailers. They were still, however, preaching mostly to a small number of the already converted.

All that changed on 25 April 2013, when Iglesias appeared on a rightwing debate show on the small channel Intereconomia. “It is a pleasure to cross enemy lines and talk,” said Iglesias by way of introduction. He was outnumbered. He would be debating against four conservative pundits. But Iglesias had come prepared and acquitted himself well. Soon, he was receiving invitations to appear on debate shows on Spain’s mainstream channels. Ratings surged as Iglesias, equipped with endless facts and a series of simple messages, wiped the floor with fellow debaters. The cocksure young lecturer usually sat with one ankle resting on a knee and an arm casually thrown behind his chair, his smile occasionally slipping into condescension. He repeated, mantra-like, that the blame for Spain’s woes lay with “la casta”, his name for the corrupt political and business elites he claimed had sold the country to the banks. The other enemy was Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel and the unelected officials who oversaw the euro from the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. Iglesias did not want Spain to leave the European Union, but he was not satisfied with it either. Above all, he wanted Spaniards to recover “sovereignty”, a concept that, like many others, remained fuzzy.

Ratings surged as Iglesias, equipped with endless facts and simple messages, wiped the floor with fellow debaters

A media star had been born. Many knew him just as “el coletas” (“the pony-tailed one”). Iglesias had spent years honing his technique, doing theatre and even attending a presenter’s course at state television RTVE’s academy. Communication, he had already declared in his PhD thesis, was key to protest. For years he and Monedero had been telling Spain’s communist-led leftwing coalition Izquierda Unida (IU) that it should learn from the Latin Americans and widen its appeal. Now they proposed a broad leftwing movement, with open primaries at which outside candidates such as Iglesias could stand. They received a firm no from IU leader Cayo Lara, who later declared that Iglesias had “the principles of Groucho Marx”. So they created it themselves.

* * *

The Podemos plan was cemented over a dinner in August 2013, during the four-day “summer university” of a tiny, radical party called Izquierda Anticapitalista (IA). Iglesias and IA heavyweight Miguel Urbán, then a then 33-year-old veteran of multiple protest movements agreed to work together, creating the strange and tense marriage between a single, charismatic leader – Iglesias – and an organisation that hates hierachy. “Pablo had political and media prestige, but that was not enough,” Urbán told me. “We needed an organisational base that stretched across the country, and that was IA.”

The plan was daring and highly improbable. It was to be an 18-month assault on power, with the ultimate aim being to replace the PSOE as leaders of the left and unseat Prime Minister Rajoy at the 2015 general election. The core clique of like-minded academics from the Complutense political sciences faculty, who were veterans of La Tuerka, would manage the campaign. At last, they would be able to try out their ideas on a national scale.

The first test for Podemos would be the May 2014 European elections. Many voters view the European parliament as toothless because the EU’s major decisions are taken elsewhere. With so little at stake, they take risks in the polling booth. Iglesias and Urbán saw the European elections as a potential springboard for their 2015 general election campaign. The party’s name – which echoes not just Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign slogan, but also a TV jingle for Spain’s European and World Cup-winning football team – came during a car journey a few months after the forming of the initial pact between Iglesias and Urbán. “We thought of ‘Yes you can!’, but that already existed,” said Urbán. “So then we went for Podemos [We Can]. It was nicely affirmative.”

On January 17 2014, Iglesias officially announced the creation of Podemos at a small theatre in Lavapiés, the hip Madrid district that over the past decade has filled up with alternative bookshops, galleries and bars. Iglesias (his eyebrow stud now removed in order to improve his electoral image) explained that a cornerstone of the Podemos project would be indignado-style “circles”, or assemblies. These circles, built around local communities or shared political interests, could meet, debate or vote in person or online. He told the crowd that if 50,000 people signed a petition on the Podemos website, he would lead a list of candidates at the European parliamentary elections in May. The target was reached within 24 hours, despite the website crashing for part of that time.

Pablo Echenique got involved with Podemos via its regional ‘circles’, and was elected as an MEP in 2014. Photograph: Jose Luis Cuesta/Cordon Press/Corbis

The Podemos project was born with two contradictions that would become increasingly apparent over time. First, it would be both radical and pragmatic in its pursuit of power. Second, it pledged to hand control to grassroots activists, despite the fact the party depended on one man’s popularity. But at the beginning, these tensions were far from most people’s minds. Excitement and idealism were the norm.

Pablo Echenique, a research physicist with spinal muscular atrophy, saw the Lavapiés speech on YouTube at his home in Zaragoza, central Spain. Three years earlier, Echenique had bumped along Zaragoza’s streets in his electric wheelchair to join the indignado protesters. He was excited by the debates, but frustrated by the lack of action. “They had no bite,” he told me. “There was no answer about what to do next.” When, four days after the Lavapiés speech, Iglesias travelled to a cultural centre beside Plaza San Agustín in Zaragoza for his first European election campaign meeting , Echenique got there early, but the 180-seat hall filled quickly. “Soon there were 500 people outside, so Pablo said: ‘I know it’s cold, but it’s worse not to have a job. We don’t fit here, so let’s go out into the plaza.’ It was freezing.”

It was in Zaragoza that Urbán first realised that Podemos might succeed. “As I waited at the door, someone asked whether I was from Podemos in Zaragoza,” Urbán told me. “I was in charge of Podemos’s organisation, but thought we didn’t really exist yet, so I just said I had come from Madrid. He replied, ‘Well, I’m from Podemos in Calatayud.’ That’s a town with just 20,000 inhabitants. Suddenly I realised that something really had changed. It was the political equivalent of occupying the squares.” A pattern was set, of packed campaign meetings that were generally ignored by the press. For those involved, it was exhilarating. Urbán took home the money gathered at the meetings to count. “We would get €2,000 from a single meeting. It was like belonging to a church,” he said.

Iglesias said politics was like sex: you start off doing it badly, but learn with experience

Echenique was inspired. “I told Pablo, ‘You say we should get organised, but I’ve never been in an organised political party. Can you give me some ideas?’ Pablo said it was like sex: you start off doing it badly, but learn with experience.” Echenique joined two circles, one in Zaragoza and one online-based group for people with disabilities. He was one of 150 candidates put forward by circles for the European parliament. These were ranked in order by 33,000 people who signed on for free to the party website. Iglesias came first and Echenique was fifth. Only one of the top 12 candidates was over 36 years old.

Podemos then embarked on the complex process of writing a “participative” election manifesto, based on ideas from the circles and then voted for online. The result was original, but also impractical and uncosted. It called for a basic state salary for all citizens and non-payment of “illegitimate” parts of the public debt, although the manifesto did not specify which parts these were – two measures that Podemos has since back-pedalled on.

The Podemos project was born with two contradictions that would become increasingly apparent over time. First, it would be both radical and pragmatic in its pursuit of power. Second, it pledged to hand control to grassroots activists, despite the fact the party depended on one man’s popularity. But at the beginning, these tensions were far from most people’s minds. Excitement and idealism were the norm.