The claims made for Mrs Thatcher's transformative powers are grossly exaggerated

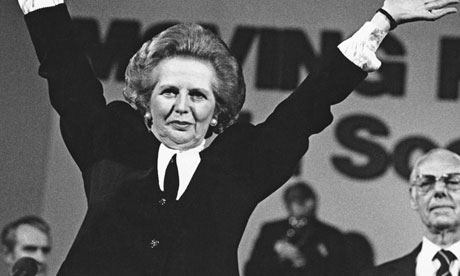

Margaret Thatcher speaking at Perth city hall, Scotland in 1987. Photograph: Neil Libbert/The Observer

The empress has no clothes or, at least, not the clothes in which so many want to robe her. Despite all the praise, Mrs Thatcher did not arrest British economic decline, launch an economic transformation or save Britain. She did, it is true, re-establish the British state's capacity to govern. But then, although she wanted to trigger a second industrial revolution and a surge of new British producers, she used the newly won state authority to worsen the very weaknesses that had plagued us for decades. The national conversation of the last six days has been based on a fraud. If the Thatcher revolution had been so transformatory, our situation today would not be so acute.

In the 20 years up to 1979, Britain's growth rate averaged 2.75%, although it had been weakening during the ills of the mid-1970s. In the years before the banking crisis, there was a vexed debate about whether the Thatcher reforms, essentially unchallenged by Blair and Brown, had succeeded in restoring the long-run growth rate to earlier levels. Certainly, the gap in per capita incomes between Britain, France and Germany had narrowed, as, apparently, had the productivity gap.

The question is whether any of it was sustainable. Now, there is a growing and dismaying recognition that too much growth in the past 30 years has been built on an unsustainable credit, banking and property bubble and that Britain's true long-run growth rate has fallen to around 2%. The productivity gap is widening. All that heightened inequality, the unbelievable executive remuneration, wholesale privatisation, taking "the shackles off business" and labour market flexibility has achieved nothing durable.

This bitter realisation has been sharpening in non-conservative circles for some months. The pound has fallen by 20% in real terms since 2008, yet the response of our export sector to the most sustained competitive advantage since we came off the gold standard has been disastrously weak. Britain's trade deficit in goods climbed to 6.9% of GDP in 2012 – the highest since 1948 – and February's numbers were cataclysmically bad. Britain simply does not have enough companies creating goods and even services that the rest of the world wants to buy, despite devaluation.

The legion of Mrs Thatcher's apologists argues she can hardly be blamed for what is happening 23 years after leaving office. But economic transformations should be enduring, shouldn't they? Thatcherism did not deliver because dynamic capitalism is achieved through a much more subtle interplay. She never understood that a complex ecosystem of public and private institutions is needed to support risk-taking, the creation of open innovation networks, sustained long-term investment and sophisticated human capital. Believing in the magic of markets and the inevitable destructiveness of the state, she never addressed these core issues. Instead, the demand for high financial returns steadily rose through her period of office, along with executive pay, even while investment and innovation sank. And the trends continued because none of her successors dared challenge what she had started.

Instead, her targets were trade unions and state-owned enterprise in the ideological project of brutally asserting the primacy of markets and the private sector, and thus a conservative hegemony, in the name of a fierce patriotism. This was real enough: she really did want to put Britain back on the map economically and politically and the task force sailing for the Falklands embodied the intensity of that impulse. But she did not pull it off, as even she acknowledged, in her more honest moments out of office.

Trade unions certainly needed the Thatcher treatment in terms of both accepting the rule of law and the need for responsibilities alongside their rights. But companies, shareholders, banks and wider finance also needed this treatment. But as "her people" and part of the hegemonic alliance she aimed to create, they would never get the same medicine. Instead, her Big Bang in 1986, allowing banks worldwide to combine investment and commercial banking in London, was a monster sweetheart deal to please her own constituency. Britain became the centre of a global financial boom, but at home this meant an intensification of the financial system's dysfunctionality, helped by little regulation and a self-defeating credit boom, worsening the anti-investment, short-termist that needed to be reformed. This is now obvious to all. But for nearly 30 years, the apparent success of Thatcherism hid the need.

However, in one serious respect, trade unions were a proper target. By the late 1970s, a handful of trade union leaders in effect co-ran the country, the beneficiaries of the failure of successive governments to bring free collective bargaining into a legal framework. This despite the fact that they could not deliver their members to agreed policies, and the third year of an incomes policy had collapsed. On this question, the Labour party was intellectually exhausted and politically bankrupt; the Conservative government under Heath had been defeated too. It had become a first order crisis of governability, even of democracy.

This was her opportunity and she seized it . The early employment acts and the victory over Arthur Scargill's NUM decisively reaffirmed that the fount of political power in the country is Parliament, at the time a crucial intervention. But she wildly overshot. Trade unions within a proper framework are a vital means of expressing employee voice and protecting worker interests. Labour market flexibility – code for deunionisation and removal of worker entitlements – has become another Thatcherite mantra that again hides the complexity of what is needed in the labour market: employee voice and engagement, skills and adaptability. When she left office, 64% of UK workers had no vocational qualifications.

The best thing that can be said about Thatcherism is that it may have been a necessary, if mistaken, staging post on the way to our economic reinvention. She resolved the crisis of governance but then demonstrated that simple anti-statism and pro-market solutions do not work. We need to do more sophisticated things than control inflation, reduce public debt, roll back the state and assert "market forces".

The coalition government is developing new-look industrial strategies, reforming the banking system and reintroducing the state – as a vital partner – into areas such as energy. New thinking is emerging everywhere. For example, in the north-east of England an economic commission chaired by Lord Adonis, of which I was a member, recently recommended the de facto reintroduction of the metropolitan authority in Newcastle, abolished by Mrs Thatcher. It would co-ordinate a pan-north-east redoubling of investment in skills and transport, along with winning more investment. And it wants the local economic partnership to work in the same building as the proposed new combined authority, driving forward an innovation and investment revolution. This complex interaction of private and public the commission is trying to develop is a world away from Thatcher – and widely welcomed.

The empress really has no clothes. Wednesday's funeral is a tribute to the myth and the conservative hegemony she created. If the royal family is concerned, as is reported, that the whole affair will be over the top, they are right. Mrs Thatcher capitalised on a moment of temporary ungovernability that, to her credit, she resolved, then sold her party and country an oversimple and false prospectus. The landslide Mr Blair won in 1997 was to challenge it, but he did not understand at the time, nor understand now, what his mandate meant. The force of events is at last moving us on. But Britain has been weakened, rather than strengthened, by the revolution she wreaked.