These relics of empire pay hardly any UK tax – but when the neighbours cut up nasty, they demand the British protect them

La Linea. ‘People living in the colonies have a right to be considered, but this has never overridden political reality. Photograph: Oli Scarff/Getty

Nothing beats a gunboat. HMS Illustrious glided out of Portsmouth on Monday, past HMS Victory and cheering crowds of patriots. Within a week it will be off Gibraltar, a mere cannon shot from Cape Trafalgar. The nation's breast heaves, the tears prick. The Olympic spirit is off to singe the king of Spain's beard. How dare they keep honest British citizens waiting six hours at Spanish border control? Have they forgotten the Armada?

The British empire had much to be said for it, but it is over – dead, deceased, struck off, no more. The idea of a British warship supposedly menacing Spain is ludicrous. Is it meant to bomb Cadiz? Will its guns lift a rush-hour tailback in a colony that most Britons regard as awash with tax dodgers, drug dealers and right-wing whingers? The Gibraltarians have rights, but why British taxpayers should send warships to enforce them, even if just "on exercise", is a mystery.

Any study of Britain's currently contentious colonies, Gibraltar and the Falklands, can reach only two conclusions. One is that Britain's claim to them in international law is wholly sound, the other is that it is nowadays wholly daft.

Twenty-first century nation states will no longer tolerate even the mild humiliation of hosting the detritus of 18th- and 19th-century empires. Most European empires were born of the realpolitik of power, mostly the treaties of Utrecht (1713) and Paris (1763). The same realpolitik now ordains their dismantling. An early purpose of the United Nations was to bring this about.

Of course those living in these colonies have a right to be considered, but such rights have never overridden political reality. Nor has Britain claimed so, at least when circumstance dictated. The residents of Hong Kong and Diego Garcia were not consulted, let alone granted "self-determination", when Britain wanted to dump them in the dustbin of history. Hong Kong was handed to China in 1997 when the New Territories lease ended. Diego Garcia was demanded by and handed to the Pentagon in 1973. The Hong Kong British were denied passports, and the Diego Garcians were summarily evicted to Mauritius and the Seychelles.

Britain's security does not need these places. It does not depend on coaling stations in the Atlantic. France survives without any longer owning Senegal and Pondicherry, and Portugal without São Tomé and Goa. When the Indians seized Goa in 1961, the world did not object. Indeed the Argentinian invasion plan for the Falklands in 1982 was called Operation Goa, as Buenos Aires assumed it would likewise be seen as a post-imperial clear-up.

Relics of the British empire now mostly survive in the interstices of the global economy. They are the major winners from the fiscal haemorrhage that has resulted from financial globalisation. Many have become synonymous with sleaze. American tax authorities wax furious over Bermuda. George Osborne is out to get the tax dodgers of the Caymans and British Virgin Islands.

Spain has long held grievances over Gibraltar's role in aiding people smuggling, money laundering and offshore gambling beyond its own regulatory reach. This culminated in a 2007 IMF report on shortcomings in the colony's financial regulation. Gibraltar's status as a tax haven has brought it surging wealth, fuelling Spain's rage at so much money pouring untaxed through what it regards as its own territory.

Such colonies claim to be "more British than the British", except that they pay no UK tax and act as tax havens for funds from Britain. Gibraltar has made a particular specialism of internet gambling. Colonies claim allegiance to the crown, but not to its exchequer, or its financial police. They are Churchillian theme parks of red pillar boxes, fish and chips and warm beer. But they want the smooth without the rough. When the neighbours cut up nasty, they demand that those whose taxes protect them should send soldiers, diplomats and lawyers to their aid.

The legal argument between Britain and Spain is in Britain's favour. Though Britain failed to join the Schengen area with free border crossings, all EU states supposedly ease the movement of their citizens. Spain's proposed £43 admission charge is excessive. It might seem ironic for Tory ministers to plead their cause before the hated European courts, but that is the right place to go. Law-law is better than play-acting at war-war.

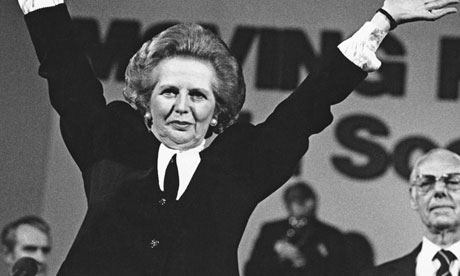

That said, it is beyond belief that an honest broker could not resolve this centuries-old dispute. Britain has, on several occasions, sought a compromise deal on Gibraltar's sovereignty. Thatcher initiated talks in 1984, after successfully settling both Rhodesia and Hong Kong. The Spaniards offered Gibraltar fully devolved status, like the Basques and Catalans, respecting language, culture and a degree of fiscal autonomy. As Hong Kong has shown, sovereignty transfer does not mean political absorption.

The curse has been Spanish ineptitude feeding Gibraltarian intransigence. Border hold-ups are counterproductive to winning hearts and minds, as were blundering Argentinian landings on the outer Falklands. Spain demanded sovereignty now – despite itself having colonies in north Africa. This pushed British governments to the wall and made them vulnerable to colonial lobbyists wielding the demand for self-determination. A 2002 Gibraltar referendum gave 98% support for continued colonial status – a Falklands vote gave a similar result. It's a far cry from Thatcher's readiness to surrender Hong Kong and accept "sovereignty with leaseback" from both Madrid and Buenos Aires.

The truth is that Britain's tax-haven colonies feel more secure than ever, blessed by history with British protection and free to skim the dark side of the global economy for cash. This has bred a tribe of gilded "Britons" who live in a perpetual other-world. When I asked a Gibraltarian who claimed to be "150% British" why he should not at least pay 100% British taxes, he replied: "Why should I pay for people thousands of miles away?"

While they deny the logic of history and geography, neither Gibraltar nor the Falklands will ever be truly "safe". One day these hangovers will somehow merge into their hinterlands and cease to be grit in the shoe of international relations. This day will be hastened if world governments take action to end tax havens.

Meanwhile, the inhabitants of Gibraltar can go on voting "to stay British" as long as they like. But if they do not accept the taxes and disciplines most Europeans accept, while sucking business from Europe's financial centres, they can hardly expect one EU state to protect them from another. An occasional six-hour queue at La Linea is a small price to pay for declining to join the real world.

• This article was amended on 14 August 2013. It originally stated that the US department of state had called Gibraltar "a major European centre of money laundering". In fact, it was referring to Spain. This has now been corrected.