'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Christianity. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Christianity. Show all posts

Friday, 8 September 2023

Wednesday, 22 July 2020

Friday, 14 April 2017

Faith still a potent presence in Western politics

Harriet Sherwood in The Guardian

Faith remains a potent presence at the highest level of UK politics despite a growing proportion of the country’s population defining themselves as non-religious, according to the author of a new book examining the faith of prominent politicians.

Nick Spencer, research director of the Theos thinktank and the lead author of The Mighty and the Almighty: How Political Leaders Do God, uses the example that all but one of Britain’s six prime ministers in the past four decades have been practising Christians to make his point.

The book examines the faith of 24 prominent politicians, mostly in Europe, the US and Australia, since 1979. “The presence and prevalence of Christian leaders, not least in some of the world’s most secular, plural and ‘modern’ countries, remains noteworthy. The idea that ‘secularisation’ would purge politics of religious commitment is surely misguided,” it concludes.

It includes “theo-political biographies” of Theresa May, an Anglican vicar’s daughter who has spoken publicly about her Christianity since taking office last July, and her predecessors David Cameron, Gordon Brown, Tony Blair and Margaret Thatcher. Only John Major is absent from the post-1979 lineup.

Spencer writes that May is a “politician with strong views rather than a strong ideology, and those views were seemingly shaped by her Christian upbringing and faith. That Christianity gives her, in her own words, ‘a moral backing to what I do, and I would hope that the decisions I take are taken on the basis of my faith’.”

May told Desert Island Discs in 2014 that Christianity had helped to frame her thinking but it was “right that we don’t flaunt these things here in British politics”. According to Spencer, “in this regard at very least, May practises what she preaches”.

However, the prime minister’s apparent reticence did not stop her lambasting Cadbury’s and the National Trust this month over their supposed downgrading of the word Easter in promotional materials and packaging.

Elsewhere, the book looks at five US presidents – Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump – five European leaders, three Australian prime ministers and Vladimir Putin of Russia. Five leaders from other countries – including Nelson Mandela – complete the list.

The “great secular hope” was that religion would fade out of the political landscape, Spencer writes. But “the last 40 years have turned out somewhat different”, with the emergence of political Islam, the strength of Catholicism in central and south America and the explosion of Pentecostalism in the global south.

Even in the west, “Christian political leaders have hardly become less prominent over recent decades, and may, in fact, have become more so,” he says.

But Spencer told the Guardian: “There is no one size fits all, politically. You don’t find them clustering on the political spectrum.”

At the rightwing end were Thatcher and Reagan. At the other was Fernando Lugo, the president of Paraguay between 2008 and 2012, a prominent Catholic “bishop of the poor”, liberation theologist and part of a wave of leftwing leaders in Latin America.

There were also significant differences in the political contexts in which Christian politicians were operating, Spencer said. “There are places where you stand to make a lot of political capital by talking about your faith – such as the US or Russia.

“But in countries like the UK, Australia, Germany, France, where electorates are hyper-sceptical, politicians stand to lose political capital. No politician in the UK or France talks about their faith in order to win over the electorate.”

Tony Blair in 2001. Photograph: Jonathan Evans/Reuters

Blair’s communications chief Alastair Campbell famously warned a television interviewer against asking the then prime minister about his faith, saying: “We don’t do God.” He believed the British public was instinctively distrustful of religiously-minded politicians.

After he left Downing Street, Blair spoke of the difficulties of talking about “religious faith in our political system. If you are in the American political system or others then you can talk about religious faith and people say ‘yes, that’s fair enough’ and it is something they respond to quite naturally. You talk about it in our system and, frankly, people do think you’re a nutter.”

Although Blair’s faith reportedly shaped all his key policy decisions in office, the same was not true of all politicians, said Spencer. “There are some politicians for whom faith has shaped politics, and others for whom you can be more confident that politics are shaping faith. Trump is an example of that,” he said.

According to the chapter on Trump – a late addition to the book – the president “is not known for his interest in theology, the church or religion. His statements about faith, not least his own faith, have been infrequent and vague. And yet, Trump is insistent that he believes in God, loves the Bible and has a good relationship with the church … Simply to dismiss Trump’s faith talk would be to dismiss Trump, and 2016 showed that that is a mistake”.

Leaders’ faith

Theresa May Daughter of an Anglican vicar, the British prime minister goes to church most Sundays and has said her Christian faith is “part of who I am and therefore how I approach things ... [it] helps to frame my thinking and my approach”.

Vladimir Putin The Russian president has increasingly presented himself as a man of serious personal faith, which some suggest is connected to a nationalist agenda. He reportedly prays daily in a small Orthodox chapel next to the presidential office.

Angela Merkel The German chancellor is a serious Christian believer but one whose faith is very private. “I am a member of the evangelical church. I believe in God and religion is also my constant companion, and has been for the whole of my life,” she told an interviewer in 2012.

Fernando Lugo The former president of Paraguay was also a prominent Catholic bishop, a champion of the poor and a leading advocate of liberation theology. He urged “defending the gospel values of truth against so many lies, justice against so much injustice, and peace against so much violence”.

Viktor Orbán A relatively recent convert to faith, the Hungarian prime minister frequently invokes the need to defend “Christian Europe” against Muslim migrants. “Christianity is not only a religion, but is also a culture on which we have built a whole civilisation,” he said in 2014.

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf The president of Liberia and a Nobel peace laureate, Sirleaf was brought up in a devout family and has frequently appealed for “God’s help and guidance” during her 10 years as head of state. In a 2010 speech, she described religion and spirituality as “the cornerstone of hope, faith and love for all peoples and races”.

Faith remains a potent presence at the highest level of UK politics despite a growing proportion of the country’s population defining themselves as non-religious, according to the author of a new book examining the faith of prominent politicians.

Nick Spencer, research director of the Theos thinktank and the lead author of The Mighty and the Almighty: How Political Leaders Do God, uses the example that all but one of Britain’s six prime ministers in the past four decades have been practising Christians to make his point.

The book examines the faith of 24 prominent politicians, mostly in Europe, the US and Australia, since 1979. “The presence and prevalence of Christian leaders, not least in some of the world’s most secular, plural and ‘modern’ countries, remains noteworthy. The idea that ‘secularisation’ would purge politics of religious commitment is surely misguided,” it concludes.

It includes “theo-political biographies” of Theresa May, an Anglican vicar’s daughter who has spoken publicly about her Christianity since taking office last July, and her predecessors David Cameron, Gordon Brown, Tony Blair and Margaret Thatcher. Only John Major is absent from the post-1979 lineup.

Spencer writes that May is a “politician with strong views rather than a strong ideology, and those views were seemingly shaped by her Christian upbringing and faith. That Christianity gives her, in her own words, ‘a moral backing to what I do, and I would hope that the decisions I take are taken on the basis of my faith’.”

May told Desert Island Discs in 2014 that Christianity had helped to frame her thinking but it was “right that we don’t flaunt these things here in British politics”. According to Spencer, “in this regard at very least, May practises what she preaches”.

However, the prime minister’s apparent reticence did not stop her lambasting Cadbury’s and the National Trust this month over their supposed downgrading of the word Easter in promotional materials and packaging.

Elsewhere, the book looks at five US presidents – Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump – five European leaders, three Australian prime ministers and Vladimir Putin of Russia. Five leaders from other countries – including Nelson Mandela – complete the list.

The “great secular hope” was that religion would fade out of the political landscape, Spencer writes. But “the last 40 years have turned out somewhat different”, with the emergence of political Islam, the strength of Catholicism in central and south America and the explosion of Pentecostalism in the global south.

Even in the west, “Christian political leaders have hardly become less prominent over recent decades, and may, in fact, have become more so,” he says.

But Spencer told the Guardian: “There is no one size fits all, politically. You don’t find them clustering on the political spectrum.”

At the rightwing end were Thatcher and Reagan. At the other was Fernando Lugo, the president of Paraguay between 2008 and 2012, a prominent Catholic “bishop of the poor”, liberation theologist and part of a wave of leftwing leaders in Latin America.

There were also significant differences in the political contexts in which Christian politicians were operating, Spencer said. “There are places where you stand to make a lot of political capital by talking about your faith – such as the US or Russia.

“But in countries like the UK, Australia, Germany, France, where electorates are hyper-sceptical, politicians stand to lose political capital. No politician in the UK or France talks about their faith in order to win over the electorate.”

Tony Blair in 2001. Photograph: Jonathan Evans/Reuters

Blair’s communications chief Alastair Campbell famously warned a television interviewer against asking the then prime minister about his faith, saying: “We don’t do God.” He believed the British public was instinctively distrustful of religiously-minded politicians.

After he left Downing Street, Blair spoke of the difficulties of talking about “religious faith in our political system. If you are in the American political system or others then you can talk about religious faith and people say ‘yes, that’s fair enough’ and it is something they respond to quite naturally. You talk about it in our system and, frankly, people do think you’re a nutter.”

Although Blair’s faith reportedly shaped all his key policy decisions in office, the same was not true of all politicians, said Spencer. “There are some politicians for whom faith has shaped politics, and others for whom you can be more confident that politics are shaping faith. Trump is an example of that,” he said.

According to the chapter on Trump – a late addition to the book – the president “is not known for his interest in theology, the church or religion. His statements about faith, not least his own faith, have been infrequent and vague. And yet, Trump is insistent that he believes in God, loves the Bible and has a good relationship with the church … Simply to dismiss Trump’s faith talk would be to dismiss Trump, and 2016 showed that that is a mistake”.

Leaders’ faith

Theresa May Daughter of an Anglican vicar, the British prime minister goes to church most Sundays and has said her Christian faith is “part of who I am and therefore how I approach things ... [it] helps to frame my thinking and my approach”.

Vladimir Putin The Russian president has increasingly presented himself as a man of serious personal faith, which some suggest is connected to a nationalist agenda. He reportedly prays daily in a small Orthodox chapel next to the presidential office.

Angela Merkel The German chancellor is a serious Christian believer but one whose faith is very private. “I am a member of the evangelical church. I believe in God and religion is also my constant companion, and has been for the whole of my life,” she told an interviewer in 2012.

Fernando Lugo The former president of Paraguay was also a prominent Catholic bishop, a champion of the poor and a leading advocate of liberation theology. He urged “defending the gospel values of truth against so many lies, justice against so much injustice, and peace against so much violence”.

Viktor Orbán A relatively recent convert to faith, the Hungarian prime minister frequently invokes the need to defend “Christian Europe” against Muslim migrants. “Christianity is not only a religion, but is also a culture on which we have built a whole civilisation,” he said in 2014.

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf The president of Liberia and a Nobel peace laureate, Sirleaf was brought up in a devout family and has frequently appealed for “God’s help and guidance” during her 10 years as head of state. In a 2010 speech, she described religion and spirituality as “the cornerstone of hope, faith and love for all peoples and races”.

Monday, 3 April 2017

Sky-gods and scapegoats: From Genesis to 9/11 to Khalid Masood, how righteous blame of 'the other' shapes human history

Andy Martin in The Independent

God as depicted in Michelangelo's fresco ‘The Creation of the Heavenly Bodies’ in the Sistine Chapel Michelangelo

Here’s a thing I bet not too many people know. Where are the new BBC offices in New York? Some may know the old location – past that neoclassical main post office in Manhattan, not far from the Empire State Building, going down towards the Hudson on 8th Avenue. But now we have brand new offices, with lots of glass and mind-numbing security. And they can be found on Liberty Street, just across West Street from Ground Zero. The site, in other words, of what was the Twin Towers. And therefore of 9/11. I’m living in Harlem so I went all the way downtown on the “A” train the other day to have a conversation with Rory Sutherland in London, who is omniscient in matters of marketing and advertising.

Here’s a thing I bet not too many people know. Where are the new BBC offices in New York? Some may know the old location – past that neoclassical main post office in Manhattan, not far from the Empire State Building, going down towards the Hudson on 8th Avenue. But now we have brand new offices, with lots of glass and mind-numbing security. And they can be found on Liberty Street, just across West Street from Ground Zero. The site, in other words, of what was the Twin Towers. And therefore of 9/11. I’m living in Harlem so I went all the way downtown on the “A” train the other day to have a conversation with Rory Sutherland in London, who is omniscient in matters of marketing and advertising.

There were 19 hijackers involved in 9/11, where Ground Zero now marks the World Trade Centre, but only one person was involved in the Westminster attack (Rex)

I was reminded as I came out again and gazed up at the imposing mass of the Freedom Tower, the top of which vanished into the mist, that just the week before I was going across Westminster Bridge, in the direction of the Houses of Parliament. It struck me, thinking in terms of sheer numbers, that over 15 years and several wars later, we have scaled down the damage from 19 highly organised hijackers in the 2001 attacks on America to one quasi-lone wolf this month in Westminster. But that it is also going to be practically impossible to eliminate random out-of-the-blue attacks like this one.

But I also had the feeling, probably shared by most people who were alive but not directly caught up in either Westminster or the Twin Towers back in 2001: there but for the grace of God go I. That, I thought, could have been me: the “falling man” jumping out of the 100th floor or the woman leaping off the bridge into the Thames. In other words, I was identifying entirely with the victims. If I wandered over to the 9/11 memorial I knew that I could see several thousand names recorded there for posterity. Those who died.

But I also had the feeling, probably shared by most people who were alive but not directly caught up in either Westminster or the Twin Towers back in 2001: there but for the grace of God go I. That, I thought, could have been me: the “falling man” jumping out of the 100th floor or the woman leaping off the bridge into the Thames. In other words, I was identifying entirely with the victims. If I wandered over to the 9/11 memorial I knew that I could see several thousand names recorded there for posterity. Those who died.

So I am not surprised that nearly everything that has been written (in English) in the days since the Westminster killings has been similarly slanted. “We must stand together” and all that. But it occurs to me now that “we” (whoever that may be) need to make more of an effort to get into the mind of the perpetrators and see the world from their point of view. Because it isn’t that difficult. You don’t have to be a Quranic scholar. Khalid Masood wasn’t. He was born, after all, Adrian Elms, and brought up in Tunbridge Wells (where my parents lived towards the end of their lives). He was one of “us”.

This second-thoughts moment was inspired in part by having lunch with thriller writer Lee Child, creator of the immortal Jack Reacher. I wrote a whole book which was about looking over his shoulder while he wrote one of his books (Make Me). He said, “You had one good thing in your book.” “Really?” says I. “What was that then?” “It was that bit where you call me ‘an evil mastermind bastard’. That has made me think a bit.”

When he finally worked out what was going on in “Mother’s Rest”, his sinister small American town, and gave me the big reveal, I had to point out the obvious, namely that he, the author, was just as much the bad guys of his narrative as the hero. He was the one who had dreamed up this truly evil plot. No one else. Those “hog farmers”, who were in fact something a lot worse than hog farmers, were his invention. Lee Child was shocked. Because up until that point he had been going along with the assumption of all fans that he is in fact Jack Reacher. He saw himself as the hero of his own story.

There were 19 hijackers involved in 9/11, where Ground Zero now marks the World Trade Centre, but only one person was involved in the Westminster attack (PA)

I only mention this because it strikes me that this “we are the good guys” mentality is so widespread and yet not in the least justified. Probably the most powerful case for saying, from a New York point of view, that we are the good guys was provided by René Girard, a French philosopher who became a fixture at Stanford, on the West Coast (dying in 2015). His name came up in the conversation with Rory Sutherland because he was taken up by Silicon Valley marketing moguls on account of his theory of “mimetic desire”. All of our desires, Girard would say, are mediated. They are not autonomous, but learnt, acquired, “imitated”. Therefore, they can be manufactured or re-engineered or shifted in the direction of eg buying a new smartphone or whatever. It is the key to all marketing. But Girard also took the view, more controversially, that Christianity was superior to all other religions. More advanced. More sympathetic. Morally ahead of the field.

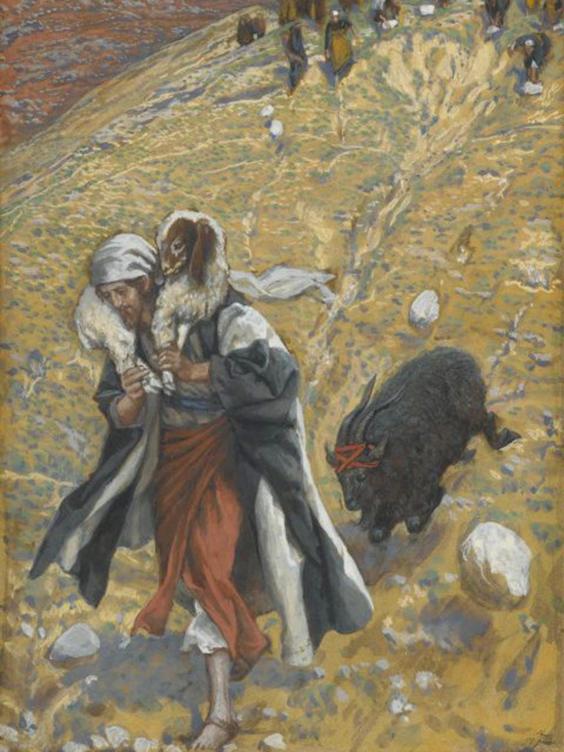

And he also explains why it is that religion and violence are so intimately related. I know the Dalai Lama doesn’t agree. He reckons that there is no such thing as a “Muslim terrorist” or a “Buddhist terrorist” because as soon as you take up violence you are abandoning the peaceful imperatives of religion. Which is all about tolerance and sweetness and light. Oh no it isn’t, says Girard, in Violence and the Sacred. Taking a long evolutionary and anthropological view, Girard argues that sacrifice has been formative in the development of homo sapiens. Specifically, the scapegoat. We – the majority – resolve our internal divisions and strife by picking on a sacrificial victim. She/he/it is thrown to the wolves in order to overcome conflict. Greater violence is averted by virtue of some smaller but significant act of violence. All hail the Almighty who therefore deigns to spare us further suffering.

In other words, human history is dominated by the scapegoat mentality. Here I have no argument with Girard. Least of all in the United States right now, where the Scapegoater-in-chief occupies the White House. But Girard goes on to argue that Christianity is superior because (a) it agrees with him that all history is about scapegoats and (b) it incorporates this insight into the Passion narrative itself. Jesus Christ was required to become a scapegoat and thereby save humankind. But by the same token Christianity is a critique of scapegoating and enables us to get beyond it. And Girard even neatly takes comfort from the anti-Christ philosopher Nietzsche, who denounced Christianity on account of it being too soft-hearted and sentimental. Cool argument. The only problem is that it’s completely wrong.

I’ve recently been reading Harold Bloom’s analysis of the Bible in The Shadow of a Great Rock. He reminds us, if we needed reminding, that the Yahweh of the Old Testament is a wrathful freak of arbitrariness. A monstrous and unpredictable kind of god, perhaps partly because he contains a whole bunch of other lesser gods that preceded him in Mesopotamian history. So naturally he gets particularly annoyed by talk of rival gods and threatens to do very bad things to anyone who worships Baal or whoever.

And he also explains why it is that religion and violence are so intimately related. I know the Dalai Lama doesn’t agree. He reckons that there is no such thing as a “Muslim terrorist” or a “Buddhist terrorist” because as soon as you take up violence you are abandoning the peaceful imperatives of religion. Which is all about tolerance and sweetness and light. Oh no it isn’t, says Girard, in Violence and the Sacred. Taking a long evolutionary and anthropological view, Girard argues that sacrifice has been formative in the development of homo sapiens. Specifically, the scapegoat. We – the majority – resolve our internal divisions and strife by picking on a sacrificial victim. She/he/it is thrown to the wolves in order to overcome conflict. Greater violence is averted by virtue of some smaller but significant act of violence. All hail the Almighty who therefore deigns to spare us further suffering.

In other words, human history is dominated by the scapegoat mentality. Here I have no argument with Girard. Least of all in the United States right now, where the Scapegoater-in-chief occupies the White House. But Girard goes on to argue that Christianity is superior because (a) it agrees with him that all history is about scapegoats and (b) it incorporates this insight into the Passion narrative itself. Jesus Christ was required to become a scapegoat and thereby save humankind. But by the same token Christianity is a critique of scapegoating and enables us to get beyond it. And Girard even neatly takes comfort from the anti-Christ philosopher Nietzsche, who denounced Christianity on account of it being too soft-hearted and sentimental. Cool argument. The only problem is that it’s completely wrong.

I’ve recently been reading Harold Bloom’s analysis of the Bible in The Shadow of a Great Rock. He reminds us, if we needed reminding, that the Yahweh of the Old Testament is a wrathful freak of arbitrariness. A monstrous and unpredictable kind of god, perhaps partly because he contains a whole bunch of other lesser gods that preceded him in Mesopotamian history. So naturally he gets particularly annoyed by talk of rival gods and threatens to do very bad things to anyone who worships Baal or whoever.

‘Agnus-Dei: The Scapegoat’ by James Tissot, painted between 1886 and 1894

Equally, if we fast forward to the very end of the Bible (ta biblia, the little books, all bundled together) we will find a lot of rabid talk about damnation and hellfire and apocalypse and the rapture and the Beast. If I remember right George Bush Jr was a great fan of the rapture, and possibly for all I know Tony Blair likewise, while they were on their knees praying together, and looked forward to the day when all true believers would be spirited off to heaven leaving the other deluded, benighted fools behind. Christianity ticks all the boxes of extreme craziness that put it right up there with the other patriarchal sky-god religions, Judaism and Islam.

But even if it were just the passion narrative, this is still a problem for the future of humankind because it suggests that scapegoating really works. It will save us from evil. “Us” being the operative word here. Because this is the argument that every “true” religion repeats over and over again, even when it appears to be saying (like the Dalai Lama) extremely nice and tolerant things: “we” are the just and the good and the saved, and “they” aren’t. There are believers and there are infidels. Insiders and outsiders (Frank Kermode makes this the crux of his study of Mark’s gospel, The Genesis of Secrecy, dedicated “To Those Outside”). Christianity never really got over the idea of the Chosen People and the Promised Land. Girard is only exemplifying and reiterating the Christian belief in their own (as the Americans used to say while annihilating the 500 nations) “manifest destiny”.

I find myself more on the side of Brigitte Bardot than René Girard. Once mythified by Roger Vadim in And God Created Woman, she is now unfairly caricatured as an Islamophobic fascist fellow-traveller. Whereas she would, I think, point out that, in terms of sacred texts, the problem begins right back in the book of Genesis, “in the beginning”, when God says “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth”. This “dominion” idea, of humans over every other entity, just like God over humans, and man over woman, is a stupid yet corrosive binary opposition that flies in the face of our whole evolutionary history.

This holier-than-thou attitude was best summed up for me in a little pamphlet a couple of besuited evangelists once put in my hand. It contained a cartoon of the world. This is what the world looks like (in their view): there are two cliffs, with a bottomless abyss between them. On the right-hand cliff we have a nice little family of well-dressed humans, man and wife and a couple of kids (all white by the way) standing outside their neat little house, with a gleaming car parked in the driveway. On the left-hand cliff we see a bunch of dumb animals, goats and sheep and cows mainly, gazing sheepishly across at the right-hand cliff, with a kind of awe and respect.

“We” are over here, “they” are over there. Us and them. “They are animals”. How many times have we heard that recently? It’s completely insane and yet a legitimate interpretation of the Bible. This is the real problem of the sky-god religions. It’s not that they are too transcendental; they are too humanist. Too anthropocentric. They just think too highly of human beings.

I’ve become an anti-humanist. I am not going to say “Je suis Charlie”. Or (least of all) “I am Khalid Masood“ either. I want to say: I am an animal. And not be ashamed of it. Which is why, when I die, I am not going to heaven. I want to be eaten by a bear. Or possibly wolves. Or creeping things that creepeth. Or even, who knows, if they are up for it, those poor old goats that we are always sacrificing.

But even if it were just the passion narrative, this is still a problem for the future of humankind because it suggests that scapegoating really works. It will save us from evil. “Us” being the operative word here. Because this is the argument that every “true” religion repeats over and over again, even when it appears to be saying (like the Dalai Lama) extremely nice and tolerant things: “we” are the just and the good and the saved, and “they” aren’t. There are believers and there are infidels. Insiders and outsiders (Frank Kermode makes this the crux of his study of Mark’s gospel, The Genesis of Secrecy, dedicated “To Those Outside”). Christianity never really got over the idea of the Chosen People and the Promised Land. Girard is only exemplifying and reiterating the Christian belief in their own (as the Americans used to say while annihilating the 500 nations) “manifest destiny”.

I find myself more on the side of Brigitte Bardot than René Girard. Once mythified by Roger Vadim in And God Created Woman, she is now unfairly caricatured as an Islamophobic fascist fellow-traveller. Whereas she would, I think, point out that, in terms of sacred texts, the problem begins right back in the book of Genesis, “in the beginning”, when God says “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth”. This “dominion” idea, of humans over every other entity, just like God over humans, and man over woman, is a stupid yet corrosive binary opposition that flies in the face of our whole evolutionary history.

This holier-than-thou attitude was best summed up for me in a little pamphlet a couple of besuited evangelists once put in my hand. It contained a cartoon of the world. This is what the world looks like (in their view): there are two cliffs, with a bottomless abyss between them. On the right-hand cliff we have a nice little family of well-dressed humans, man and wife and a couple of kids (all white by the way) standing outside their neat little house, with a gleaming car parked in the driveway. On the left-hand cliff we see a bunch of dumb animals, goats and sheep and cows mainly, gazing sheepishly across at the right-hand cliff, with a kind of awe and respect.

“We” are over here, “they” are over there. Us and them. “They are animals”. How many times have we heard that recently? It’s completely insane and yet a legitimate interpretation of the Bible. This is the real problem of the sky-god religions. It’s not that they are too transcendental; they are too humanist. Too anthropocentric. They just think too highly of human beings.

I’ve become an anti-humanist. I am not going to say “Je suis Charlie”. Or (least of all) “I am Khalid Masood“ either. I want to say: I am an animal. And not be ashamed of it. Which is why, when I die, I am not going to heaven. I want to be eaten by a bear. Or possibly wolves. Or creeping things that creepeth. Or even, who knows, if they are up for it, those poor old goats that we are always sacrificing.

Friday, 30 December 2016

Christian India

by Girish Menon

I studied in a Christian school

I speak and think in English

I have crossed the ocean

I eat animals and the holy cow

Am I a Hindu?

The government regulates my temples

'Free will' applies to the church

Ghar wapasi is frowned upon

Love crusade is the norm

How do I practise as a Hindu?

Christian India, Christian India

No Hindus left in Christian India

But look at the demographic change

The army of Jesus grows faster

With their offshore bureaucratic might

How do I survive as a

Hindu?

The Congress party hates us

So do the Communists,

Muslims and Dalits

The parliament loves Americans,

free marketers and evangelists

How do I survive as a Hindu?

Christian India, Christian India

No Hindus left in Christian India

Africans and Koreans have seen the light

Many Chinese believe in Jesus

The Nagas all used their 'free will'

to embrace the Holy Father’s gospel

The missionaries work in stealth

How do I survive as a Hindu?

Christian India, Christian India

No Hindus left in Christian India

Wednesday, 31 December 2014

Conversion: With targets & incentives, new breed of evangelical groups are like start-ups

T V Mohandas Pai in The Economic Times

The Rajya Sabha has been paralysed by the Opposition on the “Ghar Vapasi” programe of a few organisations from the right. However, if you follow the debate, it is clear that this is a political battle by the left and the left of centre parties to embarrass and discredit the right of centre party in power. Maybe even with the intent to show up the government as incapable of bringing in reforms and development. The so-called conversion debate was an excuse to paralyse the Rajya Sabha, and a great opportunity was missed to debate the issue of large-scale surreptitious conversions across India (which is the real problem).

There is no doubt that large scale conversions have been taking place across India, accelerating over the last 5 years led by evangelical groups from the West. The North East has been converted with Arunachal and Tripura being now targeted. Tribal belts across Odisha, Jharkhand, Gujarat and MP have seen large-scale conversions for several years now.

The new phenomenon over the last 5 years has been the huge increase in evangelical conversions in Chennai and Tamil Nadu, clearly visible via the vehement advertising on particular channels on TV. Andhra Pradesh, particularly the interiors, Hyderabad and the coastal regions, has been specifically targeted due to the red carpet laid by a now deceased Chief Minister whose son-in-law is a Pastor with his own outfit. The visible impact across this region to any observer shows clearly that a huge amount of money has come in and that there is targeted conversion going on. Some evangelical groups have claimed that 9-12% of undivided AP has been converted, and have sought special benefits from the State (which has been reported in the media).

There is a very sophisticated operation in place by the evangelical groups, with a clear target for souls, marketing campaigns, mass prayer and fraudulent healing meetings. Evidence is available in plenty on videos on YouTube, social media, press reports, and on the ground. Pastors have been openly tweeting about souls converted, and saving people from idol worshippers. Some pastors have tweeted with glee about converts reaching 60 million, declaring a target of 100 million, and have also requested for financial support for this openly. Violence in some areas due to this has vitiated the atmosphere. The traditional institutions of both denominations are losing out to the new age evangelicals with their sophisticated marketing, money and legion of supporters from the West. One can almost classify these groups as hyper-growth startups – with a cost per acquisition, a roadmap for acquiring followers, a fund-raising machine, and a gamified approach (with rewards and incentives) to “conquering” new markets.

Our Constitution guarantees the freedom of religion, which includes the right of the individual to choose her religion. This is not in question, and is a very important concept for a nation like ours. But this right is terribly constrained by religions, which severely punish apostasy. Our laws prohibit conversion due to inducement, allurement, undue influence, coercion, or use of supernatural threats. Every debate on TV misses this point -people argue on grounds of constitutional rights and abuse right wings groups who protest such conversion forgetting that these new age evangelicals are clearly breaking the law! They go to the desperate, and prey on their insecurities by offering education for their children, medical services for the sick, and abuse existing religious practices and traditions.

People also point to the approximate 2.3% share of this minority in the last 3 censuses to deny such conversions. Of course, the 2011 census figures on religion has strangely not been released and we need this data. However, the reason why inthe conversion numbers do not show up in the census is that conversions are happening in communities entitled to reservation benefits. It appears that they are clearly told not to reveal their conversion in the census or officially to prevent loss of benefits. Most conversions happen amongst the tribals and rural and urban poor, who are soft targets to inducements.

I have a personal experience of evangelical groups trying to convert members of my family. Two house maids who converted said that the school where their children went raised fees and due to their inability to pay, they were told they would waive it if they converted (which they were forced to do). Of course, the school was rabid in their evangelism with these children. I use a taxi company for travel over the last ten years. I have noticed over 30% of drivers have converted over the last 5 years.

When asked, inevitably they spoke about evangelicals groups that gave them free education for children and paid their medical bills, provided they converted.

It is obvious that large-scale conversion by illegal means is happening in many places and the impact is clearly visible to anybody who would choose to see openly. Some apologists ask – where are the complaints about inducement or coercion? The law needs enforcement by the police independent of complaints, as is happening when rightist groups proudly announce conversions. These rightist groups lack sophistication, but they have squarely focused attention on this large-scale conversion activity. Law enforcers need to act before this becomes a bigger flashpoint.

Reconversion to Hinduism - Challenges of Ghar Wapsi

Jug Suraiya in the Times of India

The ‘ghar wapsi’ campaign needs to rebuild the ‘ghar’ they want people to return to.

The RSS, the Hindu Mahasabha and other elements of the Sangh Parivar who want to turn India into a Hindu rashtra through mass conversions called ‘ghar wapsi’ have their work cut out for them, because they face a couple of serious obstacles in achieving their objective. And these obstacles are not their ideological opponents like Congress and Mulayam Singh Yadav’s Samajwadi Party. Nor is it the trifling matter of the Constitution, which clearly defines India as a secular republic.

No, the real problem with the so-called ‘ghar wapsi’ campaign is that many of those whom the Parivar is urging to come wapsi-ing back to their ghar didn’t belong to the ghar in the first place, which makes it difficult, semantically at least, for them to come back to it. For a lot of people being targeted for ‘reconversion’ by the Parivar belongs to tribal communities, which by and large were animists and did not belong to the Hindu fold. Indeed, as the story of Eklavya in the Mahabharata shows, tribals were given short shrift by mainstream Hinduism with its caste hierarchy: Eklavya, a tribal, is made to cut off his thumb and give it to Dronacharya as guru-dakshina because Dronacharya fears that his ‘low-born’ pupil will outdo the ‘high-born’ Arjuna in archery.

Tribals apart, many of those being ‘reconverted’ are dalits who, if anything, have been even more badly treated than tribals by casteist Hinduism, which looked down on them as being ‘untouchables’, literally and metaphorically. It was this enforced ‘untouchability’ which impelled many dalits to embrace religions like Buddhism. How can those who were considered outcasts – or ‘outcastes’- be brought back to a Hinduism which excluded them to begin with?

But perhaps the biggest problem faced by the ‘reconversionists’ is that, unlike Islam and Christianity, Hinduism has never been a proselytising religion. Before the Arya Samaj leader Swami Shraddhanand launched a programme of mass conversions in the 1920s, Hinduism never had a tradition of conversions, much less ‘reconversions’.

So before the Hindu brotherhood of the Sangh Parivar goes about converting, or ‘reconverting’, people to Hinduism it might have to do a bit of converting of Hinduism itself so as to bring proselytising within its purview. In order to bring in recruits to swell its ranks, Hinduism might have to convert, or reinvent, itself.

But should it do so, it might run a risk. To paraphrase Groucho Marx, recruits to Hinduism could well say that they did not want to join a religion which would have them as converted members.

Wednesday, 19 February 2014

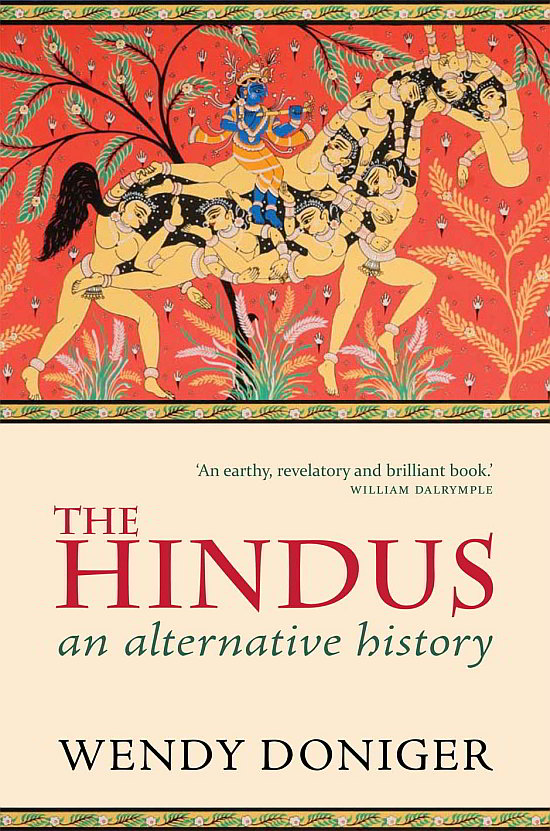

A great defence of the decision to stop publication of 'The Hindus by Wendy Doniger'

CONTROVERSY

Untangling The Knot

The many strands entangled in l' affaire Doniger involve issues that are too important to be left to the predictable and somewhat stale rhetoric about Hindutva fanatics or lamenting the role of the Indian government and judiciary

The controversy about Penguin India’s decision to withdraw and pulp Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternative History brings to the surface issues likely to trouble scholars of India for years to come. First, the obvious: the banning of any book violates academic or intellectual freedom. Rightly so, this leads to moral indignation among the intelligentsia of India and the West. Our ancestors fought for this freedom, sometimes sacrificing their lives. Not to protect it amounts to betraying their legacy.

Yet, in this case, the rhetoric is predictable and somewhat stale:

So many strands are entangled in this knotty affair that it is no longer clear what is at stake. To move ahead we first need to untangle the knot, but this requires that we take unexpected perspectives and question entrenched convictions. Drawing on the work of S.N. Balagangadhara, this piece hopes to give one such perspective.

I

Imagine you are born in the 1950s as a Hindu boy with intellectual inclinations. As you grow up, your mother takes you to the temple and shows you how to do puja. Your grandparents tell you stories about Bhima’s strength, Krishna’s appetite, Durvasa’s temper… Perhaps you rejoice when Rama rescues Sita, feel afraid when Kali fights demons, or cry when Drona demands Ekalavya’s thumb as gurudakshina. Your father is indifferent to most of this stuff, but then he is very moody so you prefer to stay away from him in any case.

In school, you are taught about the history of India. You learn that Hinduism grew out of the Brahmanism imported during the Aryan invasion. The caste system is a fourfold hierarchy imposed by the Brahmin priesthood, so you are told, and untouchability is the bane of Hindu society. Caste discrimination needs to be eradicated, as Gandhi said, while the scientific temper should displace superstitious tradition, as Nehru taught.

Your teachers present this account as the truth, along with Newton’s physics and Darwin’s evolutionary theory. You feel bad about your “backward religion” and ashamed about “the massive injustice of caste.” For some time, as a student, you also mouth this story in the name of progress and social justice. Yet you feel that there is something fundamentally wrong with it. You sense that it misrepresents you and your traditions—it distorts your practices, your people, and your experience, but you don’t know what to do about it.

What is the problem? Well, the current discourse on Indian culture and society is deeply flawed, even though it dominates the educational system and the media. This story about “Hindu religion” and “the caste system” started out as an attempt by European minds to make sense of their experience of India. Missionaries, travellers, and colonial officials collected their observations; Orientalists and other scholars ordered these into a coherent image of India. In the process, they drew on a set of commonplaces widespread in European societies, which all too often reflected a Christian critique of false religion.

The resulting story transforms India into a deficient culture:

II

Back to the 1970s now: you are studying hard, for your parents want you to become an engineer. Yet you are more interested in history and the social sciences. You want to make sense of your unease with the dominant story about Indian culture. So you turn to the works of eminent professors at elite universities from the Ivy League to JNU. What do you find? They repeat the same story, in a jargon that makes it even more opaque. You become more frustrated. Everywhere you turn, people just reproduce the same story about Hinduism and caste as the worst thing that ever happened to humanity: politicians, activists, teachers, professors, newspapers, television shows… They may add some qualifications but to no avail. After spending a few years in America, you return to India, get married, and have two kids. They come home from school with questions about “the wrongs of Hinduism and the caste system.” You don’t know what to tell them. Your frustration and anger rise to boiling point. You feel betrayed by the intellectual classes.

What are the options of Indians going through similar experiences? They cannot challenge the story about Hinduism and caste intellectually for they do not possess the tools to do so. They are neither scholars nor social scientists so they cannot be expected to grasp the conceptual foundations of the dominant story, let alone develop an alternative. Maximally, they can condemn it as “racist” or “imperialist.” Even there, they are ambiguous. They feel that the West is ahead of India in so many ways. In their society, corruption is the rule and the caste system refuses to go away, but then most people around them nevertheless appear to be good men and women. How to make sense of this? There are no thinkers able to help them solve these problems.

III

When you turn 45, your children leave home. One fine day a colleague tells you he is with the RSS and hands you some literature. Here is an outlet for venting your anger and frustration, the rhetoric of Hindu nationalism:

“Be a patriotic Indian; the Hindu nation is great; caste is only a blot on its glory; Indian intellectuals are communists engaged in an anti-Indian conspiracy; and foreign scholars must be out to divide the country.”

This rhetoric does not give you any enlightenment or insights into your traditions; actually, it feels quite shallow. But it at least gives some relief and puts an end to the blame and insult heaped onto your traditions. With some fellow warriors you decide that the miseducation of India should stop. What is the next step?

At this point, there are ready made traps. First, it is difficult not to notice how those in power in India decide what gets written in the textbooks. Under British rule, it was the classical Orientalist account. Mrs Gandhi allowed the Marxists to take control of the relevant government bodies (they could acquire only “soft power” there, after all) and reject Indian culture as a particularly backward instance of false consciousness. For decades now, secularists have set the agenda and funded research projects and centres for “humiliation and exclusion studies.” Once the BJP comes to power, why not rewrite the textbooks and run educational bodies according to Hindutva tastes?

Second, there are examples of successful attempts at having books banned in the name of religion. Rushdie’s Satanic Verses is the cause célèbre. The relevant section of the Indian Penal Code crystallized in the context of early 20th-century controversies about texts that ridiculed the Prophet Muhammad. At the time, some jurists argued that non-Muslims could not be expected to endorse the special status given by Muslims to Muhammad as the messenger of God. That would indirectly force all citizens to accept Islam as true religion. Yet it was precisely there that Muslim litigants succeeded. If one group could use the law to indirectly compel all citizens to accept its claims concerning its holy book, religious doctrines and divine prophet, why not follow the same route?

Third, American scholars of religion came in handy for once. They had identified some questions they considered central to religious studies: What is the relation between insider and outsider perspectives? Who has the right to speak for a religion, the believer or the scholar? Originally, these were questions essential to a religion like Christianity, where accepting God’s revelation is the precondition of grasping its message. Yet the potential answers turned out to be useful to others: “Only Hindus should speak for Hinduism and scholarship can be allowed only in so far as it respects the believer’s perspective.”

What gives Hindu nationalists the capacity to conform so easily to these models? This is because they generally reproduce the Orientalist story about Hinduism, just adding another value judgement. They may believe they are fighting the secularists; in fact, they are also prisoners of what Balagangadhara has called “colonial consciousness.” That is, the Western discourse about India functions as the descriptive framework through which Hindu nationalists understand themselves and their culture. They also accept that this culture is constituted by a religion with its own sacred scriptures, gods, revelations, and doctrines. Within this framework, they can then easily mimic Islamic and Christian concerns about blasphemy and offence. Add the 19th-century Victorian prudishness adopted by the Indian middle class and you get prominent strands of the Doniger affair.

Consider the petition by Dinanath Batra and the Shiksha Bachao Andolan Samiti. Doniger’s suggestion that the Ramayana is a work of fiction written by human authors—a claim that would hardly create a stir in most Indians—is now transformed into a violation of the sacred scriptures of Hinduism. The petition claims that the cover of the book is offensive because “Lord Krishna is shown sitting on buttocks of a naked woman surrounded by other naked women” and that Doniger’s approach is that “of a woman hungry of sex.” It expresses shock at her claim that some Sanskrit texts reflect the “glorious sexual openness and insight” of the era in which they were written. To anyone familiar with the harm caused by Christian attitudes towards sex-as-sin, this would count as a reason to be proud of Indian culture. Yet the grips of Victorian morality have made these Hindus ashamed of a beautiful dimension of their traditions.

IV

In the meantime, our middle-aged gentleman’s daughter has gone into the humanities and her excellent results give her entry to a PhD programme in religious studies at an Ivy League university. After some months, she begins to feel disappointed by the shallowness of the teaching and research. When compared to, say, the study of Buddhism, where a variety of perspectives flourish, Hinduism studies appears to be in a state of theoretical poverty. Refusing to take on the role of the native informant, she begins to voice her disagreement with her teachers. This is not appreciated and she soon learns that she has been branded “Hindutva.”

Around the same time, she detects a series of factual howlers and flawed translations in the works of eminent American scholars of Hinduism. When she points these out, several of her professors turn cold towards her. She is no longer invited to reading groups and is avoided at the annual meetings of the American Academy of Religion. In response, this budding researcher begins to engage in self-censorship and looks for comfort among NRI families living nearby. Her dissertation, considered groundbreaking by some international colleagues, gets hardly any response from her supervisors. Looking for a job, the difficulties grow: she needs references from her professors but whom can she ask? She applies to some excellent universities but is never shortlisted. Confidentially, a senior colleague tells her that her reputation as a Hindutva sympathiser precedes her. Eventually, she gets a tenure-track position at some university in small-town Virginia, where she feels so isolated and miserable that she decides to return to India.

Intellectual freedom can be curbed in many ways. The current academic discourse on Indian culture is as dogmatic as its advocates are intolerant of alternative paradigms. They trivialize genuine critique by reducing this to some variety of “Hindu nationalism” or “romantic revivalism.” All too often ad hominem considerations (about the presumed ideological sympathies of an author) override cognitive assessment. Thus, alternative voices in the academic study of Indian culture are actively marginalized. This modus operandi constitutes one of the causes behind the growing hostility towards the doyens of Hinduism studies.

Again this strand surfaces in the Doniger affair. When critics pointed out factual blunders from the pages of The Hindus, this appears to have been happily ignored by Doniger and her publisher. She is known for her dismissal of all opposition to her work as tantrums of the Hindutva brigade. The debates on online forums like Kafila.org (a blog run by “progressive” South Asian intellectuals) smack of contempt for the “Hindu fanatics,” “fundamentalists” or “fascists” (read Arundathi Roy’s open letter to Penguin). More importantly, they show a refusal to examine the possibility that books by Doniger and other “eminent” scholars might be problematic because of purely cognitive reasons.

For instance, the petition charges Doniger with an agenda of Christian proselytizing hidden behind the “tales of sex and violence” she tells about Hinduism. This generates ridicule: Doniger is Jewish and she is a philologist not a missionary. Indeed, this point appears ludicrous and lacks credibility when put so crudely. As said, it also reflects the Victorian prudishness to which some social layers have succumbed. Yet, it pays off to try and understand this issue from a cognitive point of view.

A major problem of early Christianity in the Roman Empire was how to distinguish true Christians from pagan idolaters. Originally, martyrdom had been a helpful criterion but, once Christianity became dominant, the persecution ended and there were no more martyrs to be found. The distinction between true and false religion could not limit itself to specific religious acts. Those who followed the true God should also be demarcated from the followers of false gods by their everyday behaviour. Sex became a central criterion here. Christians were characterized in terms of chastity as opposed to pagan debauchery. (If you wish to see how this image of Greco-Roman paganism lives on in America, watch an episode of the television series Spartacus.)

From then on, Christians believed they could recognize false religion and its followers in terms of lewd sexual practices. Early travel reports sent from India to Europe, like those of the Italian traveller Ludovico di Varthema, confirmed this image of pagan idolatry: “Brahmin priests” and “superstitious believers” engaged in a variety of “obscene” practices from deflowering virgins in various ways to swapping wives for a night or two. Conversion to Christianity would entail conversion to chastity.

Reinforced by Victorian obsessions, this style of representing Indian religion reached its climax in the late 19th century. Hinduism was said to be the prime instance of “sex worship” and “phallicism,” notions popular at the time for explaining the origin of religion. Take a work by Hargrave Jennings—cleric, freemason, amateur of comparative religion—imaginatively titledPhallic Miscellanies; Facts and Phases of Ancient and Modern Sex Worship, As Illustrated Chiefly in the Religions of India (1891). The opening sentence goes thus: “India, beyond all countries on the face of the earth, is pre-eminently the home of the worship of the Phallus—the Linga puja; it has been so for ages and remains so still. This adoration is said to be one of the chief, if not the leading dogma of the Hindu religion…”It goes on to explain that “according to the Hindus, the Linga is God and God is the Linga; the fecundator, the generator, the creator in fact.” In other words, the Hindus view the phallus as their divine Creator and its worship is their dogma. This is one of a series of works from this period, expressing both fascination and disgust.

This focus on sex remained central to the popular image of Indian religion in the Western world. In her infamous Mother India (1927), the American Katherine Mayo writes that the Hindu infant that survives the birth-strain, “a feeble creature at best, bankrupt in bone-stuff and vitality, often venereally poisoned, always predisposed to any malady that may be afloat,” is raised by a mother guided by primitive superstitions. “Because of her place in the social system, child-bearing and matters of procreation are the woman’s one interest in life, her one subject of conversation, be her caste high or low. Therefore, the child growing up in the home learns, from earliest grasp of word and act, to dwell upon sex relations” . From there, Mayo turns to a reflection on the obsession for “the male generative organ” in Hindu religion. Among the consequences are child marriage and other immoral practices: “Little in the popular Hindu code suggests self-restraint in any direction, least of all in sex relations” .

In short, the connection established between Hinduism and sexuality was based in a Christian frame that served to distinguish pagan idolaters from true believers. Wendy Doniger’s work builds on this tradition. Like some of her predecessors, she appreciates the sexual freedom involved, but then she also tends to stress two aspects: sex and caste. This is not a coincidence, for these always counted as two major properties allowing Western audiences to appreciate the supposed inferiority of Hinduism. In other words, the sense that the current depiction of Indian traditions in terms of caste and sex is connected to earlier Christian critiques of false religion cannot be dismissed so easily.

Does this mean that researchers should give in to the campaigns of holier-than-thou bigots? Does it justify the banning or withdrawal of books? Not at all! First, who will decide what counts as true knowledge and what as salacious or gratuitous insult? In the US, evangelicals would like to remove Darwin’s Origin of Species from schools because they consider it unscientific and offensive. If it continues to follow its current route, the Indian judiciary may well end up banning a variety of such books. Second, book bans fail to have any fundamental effect on the kind of work produced about India. The epitome of the “sex and caste” genre, Arthur Miles’ The Land of the Lingam(1937), was banned many decades ago. Even though political correctness altered the language use and removed explicit mockery, many works continue to represent Hinduism along similar lines. Third, the Kama Sutra and the Koka Shastra, the temples of Khajuraho and Konarak, Tantric traditions and the Indian science of erotics are all fascinating phenomena, which need to be studied and understood. But we have an equal responsibility to make sense of the concerns of Indians horrified by the currently dominant depiction of their traditions. All this research should happen in complete freedom or it shall not happen at all.

V

The dispute about Doniger’s book is a product of all these forces, including the peculiarities of the Indian Penal Code (better left to legal experts). What is the way out? How can we untangle the knot?

To cope with complex cases like these, the first step should take the form of scientific research. The disagreement with the work of Doniger and other scholars can be expressed in a reasonable manner. The theoretical poverty and shoddy way of dealing with facts and translations exhibited by such works can be challenged on cognitive grounds. This is the only way to alleviate the frustration of our Hindu gentleman (a grandfather by now) and to illuminate the intellectual concerns of his daughter. In any case, we need to appreciate how the current story about Hinduism and caste continues to reproduce ideas derived from Christianity and its conceptual frameworks. As long as we keep selling the experience that one form of life (Western culture) has had of another (Indian culture) as God-given truth, the current conflict will not abate and our understanding of India will not progress.

But the same goes for using the Indian Penal Code to have books banned. Inevitably, this has chilling effects on the search for knowledge, at a time when India needs free research more than ever to save it from catastrophe. As is always the case, scientific research will bring about unexpected and unorthodox results. At any point, some or another group may feel offended by these, but this should never prevent us from continuing to pursue truth.

Unfortunately, the Indian government and judiciary have taken the route of succumbing to “offence” and “atrocity” claims by all kinds of communities. Given the political situation, this is unlikely to change any time soon. We can express moral outrage today. But tomorrow the challenge is to develop hypotheses that make sense of the current developments in India, including the violent rejection of the dominant representations of Indian culture. These need to show the way to new solutions so that an end may be brought to the banning and destruction of books in a culture that was always known for its intellectual freedom.

Yet, in this case, the rhetoric is predictable and somewhat stale:

“Another bunch of Hindutva fanatics have succeeded in having a book by a respected academic banned because they feel offended by its contents. They have not understood the book, give ridiculous reasons, and threaten publisher and author with dire consequences if the book is not withdrawn. The Indian judiciary is caving in to religious fanaticism and practically abolishing freedom of speech in India.”This readymade reaction may sound cogent but it covers up major questions: What brings Hindu organizations to filing petitions that make them the butt of ridicule and contempt? Whence the frustration among so many Indians about the way their culture is depicted? Why is this battle not fought out in the free intellectual debate so typical of India in the past?

So many strands are entangled in this knotty affair that it is no longer clear what is at stake. To move ahead we first need to untangle the knot, but this requires that we take unexpected perspectives and question entrenched convictions. Drawing on the work of S.N. Balagangadhara, this piece hopes to give one such perspective.

I

Imagine you are born in the 1950s as a Hindu boy with intellectual inclinations. As you grow up, your mother takes you to the temple and shows you how to do puja. Your grandparents tell you stories about Bhima’s strength, Krishna’s appetite, Durvasa’s temper… Perhaps you rejoice when Rama rescues Sita, feel afraid when Kali fights demons, or cry when Drona demands Ekalavya’s thumb as gurudakshina. Your father is indifferent to most of this stuff, but then he is very moody so you prefer to stay away from him in any case.

In school, you are taught about the history of India. You learn that Hinduism grew out of the Brahmanism imported during the Aryan invasion. The caste system is a fourfold hierarchy imposed by the Brahmin priesthood, so you are told, and untouchability is the bane of Hindu society. Caste discrimination needs to be eradicated, as Gandhi said, while the scientific temper should displace superstitious tradition, as Nehru taught.

Your teachers present this account as the truth, along with Newton’s physics and Darwin’s evolutionary theory. You feel bad about your “backward religion” and ashamed about “the massive injustice of caste.” For some time, as a student, you also mouth this story in the name of progress and social justice. Yet you feel that there is something fundamentally wrong with it. You sense that it misrepresents you and your traditions—it distorts your practices, your people, and your experience, but you don’t know what to do about it.

What is the problem? Well, the current discourse on Indian culture and society is deeply flawed, even though it dominates the educational system and the media. This story about “Hindu religion” and “the caste system” started out as an attempt by European minds to make sense of their experience of India. Missionaries, travellers, and colonial officials collected their observations; Orientalists and other scholars ordered these into a coherent image of India. In the process, they drew on a set of commonplaces widespread in European societies, which all too often reflected a Christian critique of false religion.

The resulting story transforms India into a deficient culture:

“India has its dominant religion, Hinduism, created by cunning Brahmin priests; this religion sanctions social injustice in the form of a fixed caste hierarchy; instead of freedom and equality, it represents inequality and social constraint; it is basically immoral.”With some internal variation, this story is presented as a truthful description of Indian culture. Contemporary authors use different conceptual vocabularies to explain or interpret “Hinduism” and “caste,” from Marx and Freud to Foucault and Žižek. But the so-called “facts” they seek to explain are already claims of the Orientalist discourse, structured around theological ideas in secular guise. In fact, they are nothing more than reflections of how Europeans experienced India. No wonder then that the story does not make sense to those who do not share this experience.

II

Back to the 1970s now: you are studying hard, for your parents want you to become an engineer. Yet you are more interested in history and the social sciences. You want to make sense of your unease with the dominant story about Indian culture. So you turn to the works of eminent professors at elite universities from the Ivy League to JNU. What do you find? They repeat the same story, in a jargon that makes it even more opaque. You become more frustrated. Everywhere you turn, people just reproduce the same story about Hinduism and caste as the worst thing that ever happened to humanity: politicians, activists, teachers, professors, newspapers, television shows… They may add some qualifications but to no avail. After spending a few years in America, you return to India, get married, and have two kids. They come home from school with questions about “the wrongs of Hinduism and the caste system.” You don’t know what to tell them. Your frustration and anger rise to boiling point. You feel betrayed by the intellectual classes.

What are the options of Indians going through similar experiences? They cannot challenge the story about Hinduism and caste intellectually for they do not possess the tools to do so. They are neither scholars nor social scientists so they cannot be expected to grasp the conceptual foundations of the dominant story, let alone develop an alternative. Maximally, they can condemn it as “racist” or “imperialist.” Even there, they are ambiguous. They feel that the West is ahead of India in so many ways. In their society, corruption is the rule and the caste system refuses to go away, but then most people around them nevertheless appear to be good men and women. How to make sense of this? There are no thinkers able to help them solve these problems.

III

When you turn 45, your children leave home. One fine day a colleague tells you he is with the RSS and hands you some literature. Here is an outlet for venting your anger and frustration, the rhetoric of Hindu nationalism:

“Be a patriotic Indian; the Hindu nation is great; caste is only a blot on its glory; Indian intellectuals are communists engaged in an anti-Indian conspiracy; and foreign scholars must be out to divide the country.”

This rhetoric does not give you any enlightenment or insights into your traditions; actually, it feels quite shallow. But it at least gives some relief and puts an end to the blame and insult heaped onto your traditions. With some fellow warriors you decide that the miseducation of India should stop. What is the next step?

At this point, there are ready made traps. First, it is difficult not to notice how those in power in India decide what gets written in the textbooks. Under British rule, it was the classical Orientalist account. Mrs Gandhi allowed the Marxists to take control of the relevant government bodies (they could acquire only “soft power” there, after all) and reject Indian culture as a particularly backward instance of false consciousness. For decades now, secularists have set the agenda and funded research projects and centres for “humiliation and exclusion studies.” Once the BJP comes to power, why not rewrite the textbooks and run educational bodies according to Hindutva tastes?

Second, there are examples of successful attempts at having books banned in the name of religion. Rushdie’s Satanic Verses is the cause célèbre. The relevant section of the Indian Penal Code crystallized in the context of early 20th-century controversies about texts that ridiculed the Prophet Muhammad. At the time, some jurists argued that non-Muslims could not be expected to endorse the special status given by Muslims to Muhammad as the messenger of God. That would indirectly force all citizens to accept Islam as true religion. Yet it was precisely there that Muslim litigants succeeded. If one group could use the law to indirectly compel all citizens to accept its claims concerning its holy book, religious doctrines and divine prophet, why not follow the same route?

Third, American scholars of religion came in handy for once. They had identified some questions they considered central to religious studies: What is the relation between insider and outsider perspectives? Who has the right to speak for a religion, the believer or the scholar? Originally, these were questions essential to a religion like Christianity, where accepting God’s revelation is the precondition of grasping its message. Yet the potential answers turned out to be useful to others: “Only Hindus should speak for Hinduism and scholarship can be allowed only in so far as it respects the believer’s perspective.”

What gives Hindu nationalists the capacity to conform so easily to these models? This is because they generally reproduce the Orientalist story about Hinduism, just adding another value judgement. They may believe they are fighting the secularists; in fact, they are also prisoners of what Balagangadhara has called “colonial consciousness.” That is, the Western discourse about India functions as the descriptive framework through which Hindu nationalists understand themselves and their culture. They also accept that this culture is constituted by a religion with its own sacred scriptures, gods, revelations, and doctrines. Within this framework, they can then easily mimic Islamic and Christian concerns about blasphemy and offence. Add the 19th-century Victorian prudishness adopted by the Indian middle class and you get prominent strands of the Doniger affair.

Consider the petition by Dinanath Batra and the Shiksha Bachao Andolan Samiti. Doniger’s suggestion that the Ramayana is a work of fiction written by human authors—a claim that would hardly create a stir in most Indians—is now transformed into a violation of the sacred scriptures of Hinduism. The petition claims that the cover of the book is offensive because “Lord Krishna is shown sitting on buttocks of a naked woman surrounded by other naked women” and that Doniger’s approach is that “of a woman hungry of sex.” It expresses shock at her claim that some Sanskrit texts reflect the “glorious sexual openness and insight” of the era in which they were written. To anyone familiar with the harm caused by Christian attitudes towards sex-as-sin, this would count as a reason to be proud of Indian culture. Yet the grips of Victorian morality have made these Hindus ashamed of a beautiful dimension of their traditions.

IV

In the meantime, our middle-aged gentleman’s daughter has gone into the humanities and her excellent results give her entry to a PhD programme in religious studies at an Ivy League university. After some months, she begins to feel disappointed by the shallowness of the teaching and research. When compared to, say, the study of Buddhism, where a variety of perspectives flourish, Hinduism studies appears to be in a state of theoretical poverty. Refusing to take on the role of the native informant, she begins to voice her disagreement with her teachers. This is not appreciated and she soon learns that she has been branded “Hindutva.”

Around the same time, she detects a series of factual howlers and flawed translations in the works of eminent American scholars of Hinduism. When she points these out, several of her professors turn cold towards her. She is no longer invited to reading groups and is avoided at the annual meetings of the American Academy of Religion. In response, this budding researcher begins to engage in self-censorship and looks for comfort among NRI families living nearby. Her dissertation, considered groundbreaking by some international colleagues, gets hardly any response from her supervisors. Looking for a job, the difficulties grow: she needs references from her professors but whom can she ask? She applies to some excellent universities but is never shortlisted. Confidentially, a senior colleague tells her that her reputation as a Hindutva sympathiser precedes her. Eventually, she gets a tenure-track position at some university in small-town Virginia, where she feels so isolated and miserable that she decides to return to India.

Intellectual freedom can be curbed in many ways. The current academic discourse on Indian culture is as dogmatic as its advocates are intolerant of alternative paradigms. They trivialize genuine critique by reducing this to some variety of “Hindu nationalism” or “romantic revivalism.” All too often ad hominem considerations (about the presumed ideological sympathies of an author) override cognitive assessment. Thus, alternative voices in the academic study of Indian culture are actively marginalized. This modus operandi constitutes one of the causes behind the growing hostility towards the doyens of Hinduism studies.

Again this strand surfaces in the Doniger affair. When critics pointed out factual blunders from the pages of The Hindus, this appears to have been happily ignored by Doniger and her publisher. She is known for her dismissal of all opposition to her work as tantrums of the Hindutva brigade. The debates on online forums like Kafila.org (a blog run by “progressive” South Asian intellectuals) smack of contempt for the “Hindu fanatics,” “fundamentalists” or “fascists” (read Arundathi Roy’s open letter to Penguin). More importantly, they show a refusal to examine the possibility that books by Doniger and other “eminent” scholars might be problematic because of purely cognitive reasons.

For instance, the petition charges Doniger with an agenda of Christian proselytizing hidden behind the “tales of sex and violence” she tells about Hinduism. This generates ridicule: Doniger is Jewish and she is a philologist not a missionary. Indeed, this point appears ludicrous and lacks credibility when put so crudely. As said, it also reflects the Victorian prudishness to which some social layers have succumbed. Yet, it pays off to try and understand this issue from a cognitive point of view.

A major problem of early Christianity in the Roman Empire was how to distinguish true Christians from pagan idolaters. Originally, martyrdom had been a helpful criterion but, once Christianity became dominant, the persecution ended and there were no more martyrs to be found. The distinction between true and false religion could not limit itself to specific religious acts. Those who followed the true God should also be demarcated from the followers of false gods by their everyday behaviour. Sex became a central criterion here. Christians were characterized in terms of chastity as opposed to pagan debauchery. (If you wish to see how this image of Greco-Roman paganism lives on in America, watch an episode of the television series Spartacus.)

From then on, Christians believed they could recognize false religion and its followers in terms of lewd sexual practices. Early travel reports sent from India to Europe, like those of the Italian traveller Ludovico di Varthema, confirmed this image of pagan idolatry: “Brahmin priests” and “superstitious believers” engaged in a variety of “obscene” practices from deflowering virgins in various ways to swapping wives for a night or two. Conversion to Christianity would entail conversion to chastity.

Reinforced by Victorian obsessions, this style of representing Indian religion reached its climax in the late 19th century. Hinduism was said to be the prime instance of “sex worship” and “phallicism,” notions popular at the time for explaining the origin of religion. Take a work by Hargrave Jennings—cleric, freemason, amateur of comparative religion—imaginatively titledPhallic Miscellanies; Facts and Phases of Ancient and Modern Sex Worship, As Illustrated Chiefly in the Religions of India (1891). The opening sentence goes thus: “India, beyond all countries on the face of the earth, is pre-eminently the home of the worship of the Phallus—the Linga puja; it has been so for ages and remains so still. This adoration is said to be one of the chief, if not the leading dogma of the Hindu religion…”It goes on to explain that “according to the Hindus, the Linga is God and God is the Linga; the fecundator, the generator, the creator in fact.” In other words, the Hindus view the phallus as their divine Creator and its worship is their dogma. This is one of a series of works from this period, expressing both fascination and disgust.