'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label scapegoat. Show all posts

Showing posts with label scapegoat. Show all posts

Friday, 29 August 2025

Monday, 3 April 2017

Sky-gods and scapegoats: From Genesis to 9/11 to Khalid Masood, how righteous blame of 'the other' shapes human history

Andy Martin in The Independent

God as depicted in Michelangelo's fresco ‘The Creation of the Heavenly Bodies’ in the Sistine Chapel Michelangelo

Here’s a thing I bet not too many people know. Where are the new BBC offices in New York? Some may know the old location – past that neoclassical main post office in Manhattan, not far from the Empire State Building, going down towards the Hudson on 8th Avenue. But now we have brand new offices, with lots of glass and mind-numbing security. And they can be found on Liberty Street, just across West Street from Ground Zero. The site, in other words, of what was the Twin Towers. And therefore of 9/11. I’m living in Harlem so I went all the way downtown on the “A” train the other day to have a conversation with Rory Sutherland in London, who is omniscient in matters of marketing and advertising.

Here’s a thing I bet not too many people know. Where are the new BBC offices in New York? Some may know the old location – past that neoclassical main post office in Manhattan, not far from the Empire State Building, going down towards the Hudson on 8th Avenue. But now we have brand new offices, with lots of glass and mind-numbing security. And they can be found on Liberty Street, just across West Street from Ground Zero. The site, in other words, of what was the Twin Towers. And therefore of 9/11. I’m living in Harlem so I went all the way downtown on the “A” train the other day to have a conversation with Rory Sutherland in London, who is omniscient in matters of marketing and advertising.

There were 19 hijackers involved in 9/11, where Ground Zero now marks the World Trade Centre, but only one person was involved in the Westminster attack (Rex)

I was reminded as I came out again and gazed up at the imposing mass of the Freedom Tower, the top of which vanished into the mist, that just the week before I was going across Westminster Bridge, in the direction of the Houses of Parliament. It struck me, thinking in terms of sheer numbers, that over 15 years and several wars later, we have scaled down the damage from 19 highly organised hijackers in the 2001 attacks on America to one quasi-lone wolf this month in Westminster. But that it is also going to be practically impossible to eliminate random out-of-the-blue attacks like this one.

But I also had the feeling, probably shared by most people who were alive but not directly caught up in either Westminster or the Twin Towers back in 2001: there but for the grace of God go I. That, I thought, could have been me: the “falling man” jumping out of the 100th floor or the woman leaping off the bridge into the Thames. In other words, I was identifying entirely with the victims. If I wandered over to the 9/11 memorial I knew that I could see several thousand names recorded there for posterity. Those who died.

But I also had the feeling, probably shared by most people who were alive but not directly caught up in either Westminster or the Twin Towers back in 2001: there but for the grace of God go I. That, I thought, could have been me: the “falling man” jumping out of the 100th floor or the woman leaping off the bridge into the Thames. In other words, I was identifying entirely with the victims. If I wandered over to the 9/11 memorial I knew that I could see several thousand names recorded there for posterity. Those who died.

So I am not surprised that nearly everything that has been written (in English) in the days since the Westminster killings has been similarly slanted. “We must stand together” and all that. But it occurs to me now that “we” (whoever that may be) need to make more of an effort to get into the mind of the perpetrators and see the world from their point of view. Because it isn’t that difficult. You don’t have to be a Quranic scholar. Khalid Masood wasn’t. He was born, after all, Adrian Elms, and brought up in Tunbridge Wells (where my parents lived towards the end of their lives). He was one of “us”.

This second-thoughts moment was inspired in part by having lunch with thriller writer Lee Child, creator of the immortal Jack Reacher. I wrote a whole book which was about looking over his shoulder while he wrote one of his books (Make Me). He said, “You had one good thing in your book.” “Really?” says I. “What was that then?” “It was that bit where you call me ‘an evil mastermind bastard’. That has made me think a bit.”

When he finally worked out what was going on in “Mother’s Rest”, his sinister small American town, and gave me the big reveal, I had to point out the obvious, namely that he, the author, was just as much the bad guys of his narrative as the hero. He was the one who had dreamed up this truly evil plot. No one else. Those “hog farmers”, who were in fact something a lot worse than hog farmers, were his invention. Lee Child was shocked. Because up until that point he had been going along with the assumption of all fans that he is in fact Jack Reacher. He saw himself as the hero of his own story.

There were 19 hijackers involved in 9/11, where Ground Zero now marks the World Trade Centre, but only one person was involved in the Westminster attack (PA)

I only mention this because it strikes me that this “we are the good guys” mentality is so widespread and yet not in the least justified. Probably the most powerful case for saying, from a New York point of view, that we are the good guys was provided by René Girard, a French philosopher who became a fixture at Stanford, on the West Coast (dying in 2015). His name came up in the conversation with Rory Sutherland because he was taken up by Silicon Valley marketing moguls on account of his theory of “mimetic desire”. All of our desires, Girard would say, are mediated. They are not autonomous, but learnt, acquired, “imitated”. Therefore, they can be manufactured or re-engineered or shifted in the direction of eg buying a new smartphone or whatever. It is the key to all marketing. But Girard also took the view, more controversially, that Christianity was superior to all other religions. More advanced. More sympathetic. Morally ahead of the field.

And he also explains why it is that religion and violence are so intimately related. I know the Dalai Lama doesn’t agree. He reckons that there is no such thing as a “Muslim terrorist” or a “Buddhist terrorist” because as soon as you take up violence you are abandoning the peaceful imperatives of religion. Which is all about tolerance and sweetness and light. Oh no it isn’t, says Girard, in Violence and the Sacred. Taking a long evolutionary and anthropological view, Girard argues that sacrifice has been formative in the development of homo sapiens. Specifically, the scapegoat. We – the majority – resolve our internal divisions and strife by picking on a sacrificial victim. She/he/it is thrown to the wolves in order to overcome conflict. Greater violence is averted by virtue of some smaller but significant act of violence. All hail the Almighty who therefore deigns to spare us further suffering.

In other words, human history is dominated by the scapegoat mentality. Here I have no argument with Girard. Least of all in the United States right now, where the Scapegoater-in-chief occupies the White House. But Girard goes on to argue that Christianity is superior because (a) it agrees with him that all history is about scapegoats and (b) it incorporates this insight into the Passion narrative itself. Jesus Christ was required to become a scapegoat and thereby save humankind. But by the same token Christianity is a critique of scapegoating and enables us to get beyond it. And Girard even neatly takes comfort from the anti-Christ philosopher Nietzsche, who denounced Christianity on account of it being too soft-hearted and sentimental. Cool argument. The only problem is that it’s completely wrong.

I’ve recently been reading Harold Bloom’s analysis of the Bible in The Shadow of a Great Rock. He reminds us, if we needed reminding, that the Yahweh of the Old Testament is a wrathful freak of arbitrariness. A monstrous and unpredictable kind of god, perhaps partly because he contains a whole bunch of other lesser gods that preceded him in Mesopotamian history. So naturally he gets particularly annoyed by talk of rival gods and threatens to do very bad things to anyone who worships Baal or whoever.

And he also explains why it is that religion and violence are so intimately related. I know the Dalai Lama doesn’t agree. He reckons that there is no such thing as a “Muslim terrorist” or a “Buddhist terrorist” because as soon as you take up violence you are abandoning the peaceful imperatives of religion. Which is all about tolerance and sweetness and light. Oh no it isn’t, says Girard, in Violence and the Sacred. Taking a long evolutionary and anthropological view, Girard argues that sacrifice has been formative in the development of homo sapiens. Specifically, the scapegoat. We – the majority – resolve our internal divisions and strife by picking on a sacrificial victim. She/he/it is thrown to the wolves in order to overcome conflict. Greater violence is averted by virtue of some smaller but significant act of violence. All hail the Almighty who therefore deigns to spare us further suffering.

In other words, human history is dominated by the scapegoat mentality. Here I have no argument with Girard. Least of all in the United States right now, where the Scapegoater-in-chief occupies the White House. But Girard goes on to argue that Christianity is superior because (a) it agrees with him that all history is about scapegoats and (b) it incorporates this insight into the Passion narrative itself. Jesus Christ was required to become a scapegoat and thereby save humankind. But by the same token Christianity is a critique of scapegoating and enables us to get beyond it. And Girard even neatly takes comfort from the anti-Christ philosopher Nietzsche, who denounced Christianity on account of it being too soft-hearted and sentimental. Cool argument. The only problem is that it’s completely wrong.

I’ve recently been reading Harold Bloom’s analysis of the Bible in The Shadow of a Great Rock. He reminds us, if we needed reminding, that the Yahweh of the Old Testament is a wrathful freak of arbitrariness. A monstrous and unpredictable kind of god, perhaps partly because he contains a whole bunch of other lesser gods that preceded him in Mesopotamian history. So naturally he gets particularly annoyed by talk of rival gods and threatens to do very bad things to anyone who worships Baal or whoever.

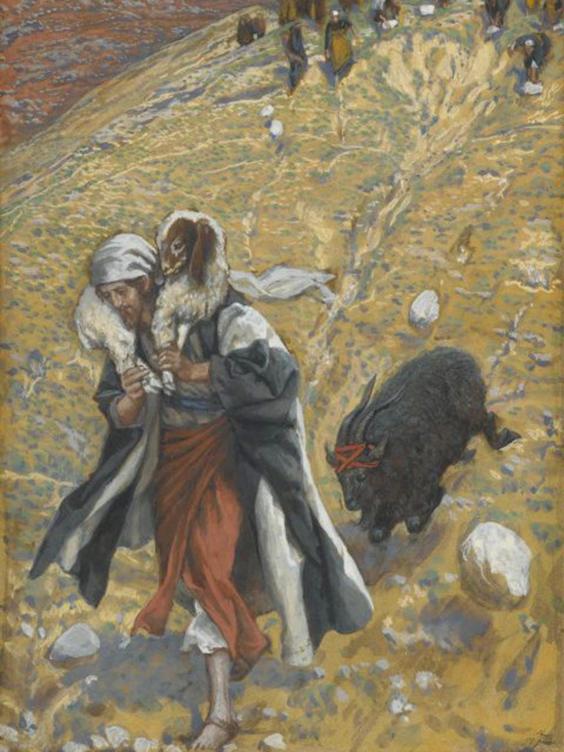

‘Agnus-Dei: The Scapegoat’ by James Tissot, painted between 1886 and 1894

Equally, if we fast forward to the very end of the Bible (ta biblia, the little books, all bundled together) we will find a lot of rabid talk about damnation and hellfire and apocalypse and the rapture and the Beast. If I remember right George Bush Jr was a great fan of the rapture, and possibly for all I know Tony Blair likewise, while they were on their knees praying together, and looked forward to the day when all true believers would be spirited off to heaven leaving the other deluded, benighted fools behind. Christianity ticks all the boxes of extreme craziness that put it right up there with the other patriarchal sky-god religions, Judaism and Islam.

But even if it were just the passion narrative, this is still a problem for the future of humankind because it suggests that scapegoating really works. It will save us from evil. “Us” being the operative word here. Because this is the argument that every “true” religion repeats over and over again, even when it appears to be saying (like the Dalai Lama) extremely nice and tolerant things: “we” are the just and the good and the saved, and “they” aren’t. There are believers and there are infidels. Insiders and outsiders (Frank Kermode makes this the crux of his study of Mark’s gospel, The Genesis of Secrecy, dedicated “To Those Outside”). Christianity never really got over the idea of the Chosen People and the Promised Land. Girard is only exemplifying and reiterating the Christian belief in their own (as the Americans used to say while annihilating the 500 nations) “manifest destiny”.

I find myself more on the side of Brigitte Bardot than René Girard. Once mythified by Roger Vadim in And God Created Woman, she is now unfairly caricatured as an Islamophobic fascist fellow-traveller. Whereas she would, I think, point out that, in terms of sacred texts, the problem begins right back in the book of Genesis, “in the beginning”, when God says “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth”. This “dominion” idea, of humans over every other entity, just like God over humans, and man over woman, is a stupid yet corrosive binary opposition that flies in the face of our whole evolutionary history.

This holier-than-thou attitude was best summed up for me in a little pamphlet a couple of besuited evangelists once put in my hand. It contained a cartoon of the world. This is what the world looks like (in their view): there are two cliffs, with a bottomless abyss between them. On the right-hand cliff we have a nice little family of well-dressed humans, man and wife and a couple of kids (all white by the way) standing outside their neat little house, with a gleaming car parked in the driveway. On the left-hand cliff we see a bunch of dumb animals, goats and sheep and cows mainly, gazing sheepishly across at the right-hand cliff, with a kind of awe and respect.

“We” are over here, “they” are over there. Us and them. “They are animals”. How many times have we heard that recently? It’s completely insane and yet a legitimate interpretation of the Bible. This is the real problem of the sky-god religions. It’s not that they are too transcendental; they are too humanist. Too anthropocentric. They just think too highly of human beings.

I’ve become an anti-humanist. I am not going to say “Je suis Charlie”. Or (least of all) “I am Khalid Masood“ either. I want to say: I am an animal. And not be ashamed of it. Which is why, when I die, I am not going to heaven. I want to be eaten by a bear. Or possibly wolves. Or creeping things that creepeth. Or even, who knows, if they are up for it, those poor old goats that we are always sacrificing.

But even if it were just the passion narrative, this is still a problem for the future of humankind because it suggests that scapegoating really works. It will save us from evil. “Us” being the operative word here. Because this is the argument that every “true” religion repeats over and over again, even when it appears to be saying (like the Dalai Lama) extremely nice and tolerant things: “we” are the just and the good and the saved, and “they” aren’t. There are believers and there are infidels. Insiders and outsiders (Frank Kermode makes this the crux of his study of Mark’s gospel, The Genesis of Secrecy, dedicated “To Those Outside”). Christianity never really got over the idea of the Chosen People and the Promised Land. Girard is only exemplifying and reiterating the Christian belief in their own (as the Americans used to say while annihilating the 500 nations) “manifest destiny”.

I find myself more on the side of Brigitte Bardot than René Girard. Once mythified by Roger Vadim in And God Created Woman, she is now unfairly caricatured as an Islamophobic fascist fellow-traveller. Whereas she would, I think, point out that, in terms of sacred texts, the problem begins right back in the book of Genesis, “in the beginning”, when God says “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth”. This “dominion” idea, of humans over every other entity, just like God over humans, and man over woman, is a stupid yet corrosive binary opposition that flies in the face of our whole evolutionary history.

This holier-than-thou attitude was best summed up for me in a little pamphlet a couple of besuited evangelists once put in my hand. It contained a cartoon of the world. This is what the world looks like (in their view): there are two cliffs, with a bottomless abyss between them. On the right-hand cliff we have a nice little family of well-dressed humans, man and wife and a couple of kids (all white by the way) standing outside their neat little house, with a gleaming car parked in the driveway. On the left-hand cliff we see a bunch of dumb animals, goats and sheep and cows mainly, gazing sheepishly across at the right-hand cliff, with a kind of awe and respect.

“We” are over here, “they” are over there. Us and them. “They are animals”. How many times have we heard that recently? It’s completely insane and yet a legitimate interpretation of the Bible. This is the real problem of the sky-god religions. It’s not that they are too transcendental; they are too humanist. Too anthropocentric. They just think too highly of human beings.

I’ve become an anti-humanist. I am not going to say “Je suis Charlie”. Or (least of all) “I am Khalid Masood“ either. I want to say: I am an animal. And not be ashamed of it. Which is why, when I die, I am not going to heaven. I want to be eaten by a bear. Or possibly wolves. Or creeping things that creepeth. Or even, who knows, if they are up for it, those poor old goats that we are always sacrificing.

Saturday, 3 October 2015

How to blame less and learn more

Mathew Syed in The Guardian

Accountability. We hear a lot about it. It’s a buzzword. Politicians should be accountable for their actions; social workers for the children they are supervising; nurses for their patients. But there’s a catastrophic problem with our concept of accountability.

Consider the case of Peter Connelly, better known as Baby P, a child who died at the hands of his mother, her boyfriend and her boyfriend’s brother in 2007. The perpetrators were sentenced to prison. But the media focused its outrage on a different group: mainly his social worker, Maria Ward, and Sharon Shoesmith, director of children’s services. The local council offices were surrounded by a crowd holding placards. In interviews, protesters and politicians demanded their sacking. “They must be held accountable,” it was said.

Many were convinced that the social work profession would improve its performance in the aftermath of the furore. This is what people think accountability looks like: a muscular response to failure. It is about forcing people to sit up and take responsibility. As one pundit put it: “It will focus minds.”

But what really happened? Did child services improve? In fact, social workers started leaving the profession en masse. The numbers entering the profession also plummeted. In one area, the council had to spend £1.5m on agency social work teams because it didn’t have enough permanent staff to handle a jump in referrals.

Those who stayed in the profession found themselves with bigger caseloads and less time to look after the interests of each child. They also started to intervene more aggressively, terrified that a child under their supervision would be harmed. The number of children removed from their families soared. £100m was needed to cope with new child protection orders.

Crucially, defensiveness started to infiltrate every aspect of social work. Social workers became cautious about what they documented. The bureaucratic paper trails got longer, but the words were no longer about conveying information, they were about back-covering. Precious information was concealed out of sheer terror of the consequences.

Almost every commentator estimates that the harm done to children following the attempt to “increase accountability” was high indeed. Performance collapsed. The number of children killed at the hands of their parents increased by more than 25% in the year following the outcry and remained higher for every one of the next three years.

Let us take a step back. One of the most well-established human biases is called the fundamental attribution error. It is about how the sense-making part of the brain blames individuals, rather than systemic factors, when things go wrong. When volunteers are shown a film of a driver cutting across lanes, for example, they infer that he is selfish and out of control. And this inference may indeed turn out to be true. But the situation is not always as cut-and-dried.

After all, the driver may have the sun in his eyes or be swerving to avoid a car. To most observers looking from the outside in, these factors do not register. It is not because they don’t think such possibilities are irrelevant, it is that often they don’t even consider them. The brain just sees the simplest narrative: “He’s a homicidal fool!”

Even in an absurdly simple event like this, then, it pays to pause to look beneath the surface, to challenge the most reductionist narrative. This is what aviation, as an industry, does. When mistakes are made, investigations are conducted. A classic example comes from the 1940s where there was a series of seemingly inexplicable accidents involving B-17 bombers. Pilots were pressing the wrong switches. Instead of pressing the switch to lift the flaps, they were pressing the switch to lift the landing gear.

Should they have been penalised? Or censured? The industry commissioned an investigator to probe deeper. He found that the two switches were identical and side by side. Under the pressure of a difficult landing, pilots were pressing the wrong switch. It was an error trap, an indication that human error often emerges from deeper systemic factors. The industry responded not by sacking the pilots but by attaching a rubber wheel to the landing-gear switch and a small flap shape to the flaps control. The buttons now had an intuitive meaning, easily identified under pressure. Accidents of this kind disappeared overnight.

This is sometimes called forward accountability: the responsibility to learn lessons so that future people are not harmed by avoidable mistakes.

But isn’t this soft? Won’t people get sloppy if they are not penalised for mistakes? The truth is quite the reverse. If, after proper investigation, it turns out that a person was genuinely negligent, then punishment is not only justifiable, but imperative. Professionals themselves demand this. In aviation, pilots are the most vocal in calling for punishments for colleagues who get drunk or demonstrate gross carelessness. And yet justifiable blame does not undermine openness. Management has the time to find out what really happened, giving professionals the confidence that they can speak up without being penalised for honest mistakes.

In 2001, the University of Michigan Health System introduced open reporting, guaranteeing that clinicians would not be pre-emptively blamed. As previously suppressed information began to flow, the system adapted. Reports of drug administration problems led to changes in labelling. Surgical errors led to redesigns of equipment. Malpractice claims dropped from 262 to 83. The number of claims against the University of Illinois Medical Centre fell by half in two years following a similar change. This is the power of forward accountability.

High-performance institutions, such as Google, aviation and pioneering hospitals, have grasped a precious truth. Failure is inevitable in a complex world. The key is to harness these lessons as part of a dynamic process of change. Kneejerk blame may look decisive, but it destroys the flow of information. World-class organisations interrogate errors, learn from them, and only blame after they have found out what happened.

And when Lord Laming reported on Baby P in 2009? Was blame of social workers justified? There were allegations that the report’s findings were prejudged. Even the investigators seemed terrified about what might happen to them if they didn’t appease the appetite for a scapegoat. It was final confirmation of how grotesquely distorted our concept of accountability has become.

Accountability. We hear a lot about it. It’s a buzzword. Politicians should be accountable for their actions; social workers for the children they are supervising; nurses for their patients. But there’s a catastrophic problem with our concept of accountability.

Consider the case of Peter Connelly, better known as Baby P, a child who died at the hands of his mother, her boyfriend and her boyfriend’s brother in 2007. The perpetrators were sentenced to prison. But the media focused its outrage on a different group: mainly his social worker, Maria Ward, and Sharon Shoesmith, director of children’s services. The local council offices were surrounded by a crowd holding placards. In interviews, protesters and politicians demanded their sacking. “They must be held accountable,” it was said.

Many were convinced that the social work profession would improve its performance in the aftermath of the furore. This is what people think accountability looks like: a muscular response to failure. It is about forcing people to sit up and take responsibility. As one pundit put it: “It will focus minds.”

But what really happened? Did child services improve? In fact, social workers started leaving the profession en masse. The numbers entering the profession also plummeted. In one area, the council had to spend £1.5m on agency social work teams because it didn’t have enough permanent staff to handle a jump in referrals.

Those who stayed in the profession found themselves with bigger caseloads and less time to look after the interests of each child. They also started to intervene more aggressively, terrified that a child under their supervision would be harmed. The number of children removed from their families soared. £100m was needed to cope with new child protection orders.

Crucially, defensiveness started to infiltrate every aspect of social work. Social workers became cautious about what they documented. The bureaucratic paper trails got longer, but the words were no longer about conveying information, they were about back-covering. Precious information was concealed out of sheer terror of the consequences.

Almost every commentator estimates that the harm done to children following the attempt to “increase accountability” was high indeed. Performance collapsed. The number of children killed at the hands of their parents increased by more than 25% in the year following the outcry and remained higher for every one of the next three years.

Let us take a step back. One of the most well-established human biases is called the fundamental attribution error. It is about how the sense-making part of the brain blames individuals, rather than systemic factors, when things go wrong. When volunteers are shown a film of a driver cutting across lanes, for example, they infer that he is selfish and out of control. And this inference may indeed turn out to be true. But the situation is not always as cut-and-dried.

After all, the driver may have the sun in his eyes or be swerving to avoid a car. To most observers looking from the outside in, these factors do not register. It is not because they don’t think such possibilities are irrelevant, it is that often they don’t even consider them. The brain just sees the simplest narrative: “He’s a homicidal fool!”

Even in an absurdly simple event like this, then, it pays to pause to look beneath the surface, to challenge the most reductionist narrative. This is what aviation, as an industry, does. When mistakes are made, investigations are conducted. A classic example comes from the 1940s where there was a series of seemingly inexplicable accidents involving B-17 bombers. Pilots were pressing the wrong switches. Instead of pressing the switch to lift the flaps, they were pressing the switch to lift the landing gear.

Should they have been penalised? Or censured? The industry commissioned an investigator to probe deeper. He found that the two switches were identical and side by side. Under the pressure of a difficult landing, pilots were pressing the wrong switch. It was an error trap, an indication that human error often emerges from deeper systemic factors. The industry responded not by sacking the pilots but by attaching a rubber wheel to the landing-gear switch and a small flap shape to the flaps control. The buttons now had an intuitive meaning, easily identified under pressure. Accidents of this kind disappeared overnight.

This is sometimes called forward accountability: the responsibility to learn lessons so that future people are not harmed by avoidable mistakes.

But isn’t this soft? Won’t people get sloppy if they are not penalised for mistakes? The truth is quite the reverse. If, after proper investigation, it turns out that a person was genuinely negligent, then punishment is not only justifiable, but imperative. Professionals themselves demand this. In aviation, pilots are the most vocal in calling for punishments for colleagues who get drunk or demonstrate gross carelessness. And yet justifiable blame does not undermine openness. Management has the time to find out what really happened, giving professionals the confidence that they can speak up without being penalised for honest mistakes.

In 2001, the University of Michigan Health System introduced open reporting, guaranteeing that clinicians would not be pre-emptively blamed. As previously suppressed information began to flow, the system adapted. Reports of drug administration problems led to changes in labelling. Surgical errors led to redesigns of equipment. Malpractice claims dropped from 262 to 83. The number of claims against the University of Illinois Medical Centre fell by half in two years following a similar change. This is the power of forward accountability.

High-performance institutions, such as Google, aviation and pioneering hospitals, have grasped a precious truth. Failure is inevitable in a complex world. The key is to harness these lessons as part of a dynamic process of change. Kneejerk blame may look decisive, but it destroys the flow of information. World-class organisations interrogate errors, learn from them, and only blame after they have found out what happened.

And when Lord Laming reported on Baby P in 2009? Was blame of social workers justified? There were allegations that the report’s findings were prejudged. Even the investigators seemed terrified about what might happen to them if they didn’t appease the appetite for a scapegoat. It was final confirmation of how grotesquely distorted our concept of accountability has become.

Monday, 15 December 2014

We are being lied to about immigration - it is politicians, not migrants, who have run down our public services

Ian Birrell in The Independent

Myths and mantras are swirling around the increasingly-toxic immigration debate as mainstream parties flounder in the

face of Ukip’s insurgency. These include the old favourite that no-one is ever

allowed to discuss the issue due to political correctness, when papers and

political discourse have been swamped by the subject for years. Or claims the

British public was never asked about allowing in floods of foreigners, despite

elections contested by parties displaying a range of stances from sympathy to

outright hostility.

But perhaps the

biggest falsehood, frequently heard reverberating around the Westminster

echo chamber, is that immigrants undermine Britain Westminster

Take the health

service. There is regular tiresome talk of crackdowns on ‘health tourism’,

although the young European migrants moving to this country are far less likely

to be a drain on health care than the one million mainly-elderly Britons who have

moved to Spain

Yet as Stephen

Nickell from the Office for Budget Responsibility reminded MPs last week, the

NHS would be in dire straits without migrant staff. They have come from more

than 200 countries. More than one quarter of doctors and one in seven of all

qualified clinical staff in hospitals and surgeries are foreign nationals -

along with a huge number of carers (as I have seen from grateful personal

experience with my profoundly disabled daughter).

Instead of condemning immigrants for

threatening the welfare state, politicians should be praising them to the

heavens for supporting the nation’s most precious public service. And this is

ignoring the dry economic reality that they contribute more to the exchequer

than they take out, as shown by scores of studies, as well as being more likely

than native-born Britons to set up businesses and less likely to claim benefits.

Then there are

schools. One of the most remarkable recent stories in global education has been

the astonishing turnaround of London Britain

Academics are

grappling with this phenomenon. And their studies indicate immigration lies

behind this transformation, as well as helping drive London Bristol

University

So much for Farage’s

claims that immigrants are wrecking public services and ruining the quality of

life in Britain

Clearly

there are pressures when a country’s population increases fast - although our

rise is also down to welcome increases in life expectancy and birthrates. Yet

migrants have become the proxy for any problem, the easy target for almost any

issue. But if there are too few doctors’ surgeries and primary schools, whose

fault is that? Who should be blamed for decades of failure to build enough

houses? Or for the low skills of too many school leavers and the shameful

poverty of expectation that failed generations of working class kids?

Immigrants contributing to our prosperity and public services - or politicians

who failed to plan for the future?

This stench of

hypocrisy wafts perhaps most strongly over the issue of housing. For at least

two decades, Britain

Now immigrants get

the blame and there are complaints of over-crowding; in fact, less than

one-tenth of England

Tuesday, 11 February 2014

Switzerland's immigration 'victory' over the EU is a fairytale sold by the far right

Eurosceptics are lining up in praise of the defiant vote, but the fallout for Swiss people could be devastating

The French National Front party leader Marine Le Pen. Photograph: Nicolas Tucat/AFP/Getty Images

The winners of the Swiss referendum on EU immigration now tell a story that has become ingrained in Swiss lore: that poor, powerless peasants have cast off their evil foreign lords and masters. Not surprising, then, that after engineering the victory, the billionaire member of parliament Christoph Blocher, of the populist rightwing Swiss Peoples Party (SVP), stated: "Now we take power in our own hands again, the government must represent the will of the Swiss people in Brussels – the sooner the better."

The supposed victory of the Swiss David over the EU Goliath has been applauded by Geert Wilders of the Dutch far-right Freedom Party (PVV) and in France by Marine Le Pen's National Front. The Eurosceptic FPÖ in Austria and the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) are also now demanding that voters in their countries should have the same say on EU matters, particularly immigration.

Switzerland, however, is a poor model for these countries to emulate. The Swiss don't need an EU exit because all they have is à la carte bilateral accords with the union. The free movement of citizens was the bitter pill the right had to swallow for goodies such as participation in EU research programmes, transit agreements, or police and asylum co-operation. Thanks to the latter, Switzerland can, for example, repatriate asylum seekers to EU countries.

If Britain, the Netherlands and other countries think they can break away from the EU while cherry-picking the bits they still want, like the Swiss have, they are dreaming. Switzerland could only ever opt for an all-or-nothing agreement – with a guillotine clause. This means that if one bilateral agreement is broken, as far as the EU is concerned all the rest is invalid too, and the fallout is potentially devastating. The Swiss business community, our hospitals, schools and colleges, tourism and the building industry which rely on an EU workforce are appalled. Students who benefit from EU exchange programmes and the energy sector which wants to sell its storage capacity to the EU all now fear that their future is called into question.

To see Switzerland as a role model for autonomy or the repatriation of sovereignty is a misjudgment of the reality. The more bilateral accords Switzerland gathered, the clearer it became that Switzerland was merely enacting EU law in a "self-governed" way. Autonomy was an illusion. In 2012, the council and the commission of the EU made clear to the Swiss that no new bilateral agreements would be possible unless Switzerland took on board all future EU reforms and developments. Since then, Swiss demands for a bilateral agreement on services and energy have stalled – and now there will be no accord anytime soon.

Of course, Blocher and his followers still believe that the EU will give us a helping hand whenever we need it. But what EU governments want from Switzerland is tax on the undeclared money of their citizens deposited in Swiss banks. Blocher's story of the poor peasant who opposes the foreign king is, in the face of Swiss wealth, ridiculous. The Italians whose workers are no longer welcome in Switzerland now say they want the tax being hidden by Italians in Swiss bank accounts – and if necessary they will name and shame tax dodgers like Germany does.

If anything Switzerland should be a bad model for EU countries. It was not only ultra-conservatives in the Swiss-German countryside who voted in favour of ending EU immigration. It was also the many workers, faced with competition from cheaper migrant labour, commuters in overcrowded trains and middle-class families who can no longer afford flats in the cities. Yet these moderate voters – they are estimated to account for 20% of the yes voters – received little to calm their fears. They wanted rent controls, measures to guard against wage dumping and minimum salaries. But there was no clear support from employer associations, the companies that profit most from the free movement of workers, nor the government.

So their perfectly rational concerns were exploited by the fear campaign waged by the rich Pied Pipers of the right. There are many more such Pied Pipers going around Europe with easy, popular solutions, including the scapegoating of immigrants, in an attempt to win the votes of those with justifiable fears. Switzerland has an unemployment rate of 3.5%; there is a lot to lose.

Switzerland is not a model for more wealth with autonomy in the EU. Its competitive advantages such as banking secrecy and low holding taxation are waning, and its most important resource, the brain power of the people, is now curtailed by immigration quotas. Switzerland is a stark warning to those EU companies, organisations and professionals who reap the fruits of the single market and the globalised economy, while giving little or no thought to the millions of ordinary workers who would miss out if the EU project came unstuck.

Wednesday, 15 January 2014

England's reusable scapegoat

Andrew Hughes in Cricinfo

"Some day, if you play your cards right, you just might turn into a proper sacrificial lamb" © AFP

Enlarge

Generally speaking, the Old Testament hasn't much to teach us about cricket. Yet as England continue to wander in a dry, harsh and unforgiving land in search of victory, it seems that certain members of that benighted tribe of outcasts have been taking advice from a passage in Leviticus:

Then he is to take the two goats and present them before the Lord at the entrance to the tent of meeting. He is to cast lots for the two goats - one lot for the Lord and the other for the scapegoat. The goat chosen by lot as the scapegoat shall be presented alive before the Lord to be used for making atonement by sending it into the wilderness…

It's a simple idea. If you've done something you're not too proud of, perhaps pretending you hadn't hit a ball with your bat when really you had, eating too many shellfish fairy cakes or losing five Test matches in a row, then simply find yourself a tame quadruped, stick a piece of paper inscribed with the words "Sorry about all that" on its horns, and point it in the general direction of the countryside. Hey presto, all is forgiven.

Still, as splendid as this tradition is, these days people are less likely to be impressed by goat-based rituals of atonement than they were in Biblical times. A higher order of mammal altogether is required. Step forward Kevin Peter Pietersen.

That's the great thing about having a talented foreigner in your team. Not only can he win matches for you, but when the time comes to turf him out, no one really minds because he isn't English anyway. KP has been particularly valuable because he's a reusable scapegoat, an economy that the profligate men of the Bible clearly hadn't considered.

The ritual is already well underway. Journalists are clamouring for blood, Andy Flower has been spotted picking up his sacrificial robes from the dry cleaners, and Alastair Cook has refused to speculate on the identity of the tall South African-born goat they've got in mind.

But Kevin should not despair. He may not enjoy playing the role of the shunned ruminant, but he should remember that the scapegoat generally fared better than your average Biblical goat, not to mention your average Biblical sheep, ram, bull or fatted calf.

And this particular version of the old Bible story is likely to turn out rather well for the goat when he falls in with some other goats, travels to India to play in the Indian Goat League, becomes one of the richest goats on the planet and tweets photographs of himself sitting in a stretch limousine eating fresh grass out of a solid gold manger to his adoring fans, while Flower and Cook sit huddled in their ECB bunker, contemplating their 27th consecutive Test defeat and considering whether to abandon little Joe Root on a mountain top in the hope that it might bring them good luck.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)

.png)

.png)