'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label sacrifice. Show all posts

Showing posts with label sacrifice. Show all posts

Thursday, 23 December 2021

Monday, 27 July 2020

Lay-offs are the worst of the bleak options facing recession-hit companies

Some groups are becoming more creative, offering short-time working rather than redundancies observes Andrew Hill in the FT

From the videotapes to the workplace hugs, much of Broadcast News, the 1987 satire on media, looks old-fashioned. But when I watched the film again recently, as an escape from pandemic-provoked gloom, the scene where the network announces a round of redundancies seemed raw and relevant.

“If there’s anything I can do,” says the network director, relieved at how a veteran newsman has accepted the news of his forced early retirement. “Well, I certainly hope you die soon,” responds the departing colleague.

Similar scenes are playing out at companies around the world. Marks and Spencer, the retailer, Melrose, which owns venerable manufacturer GKN, New York-based Macy’s department store, and European aircraft-maker Airbus have all announced potential cuts in recent weeks. Manufacturing trade group Make UK has warned of a “jobs bloodbath”. Newsrooms have been particularly hard hit.

One added twist is that some of today’s lay-off conversations with unlucky staff will take place by video link rather than in person — easier for nervous managers, but crueller for the people they are laying off.

Another, more positive, development is that companies are becoming more creative as they brace for recession, turning to short-time working rather than lay-offs. As governments remove subsidies, what was a simple decision to hold staff in reserve, rather than fire them, will become more complicated. But avoiding permanent cuts makes sense, according to David Cote, former chief executive of Honeywell. The sheer cost of severance — in time, money and administrative hassle — mounts up. Often you have to hire the staff back to meet demand as the economy recovers.

“If someone told you that it would take you six months to build a factory, six months to recover your investment, you’ll get a return for six months, and then you’ll shut it down, you’d never go for it because it would be ridiculous,” he writes in his new book Winning Now, Winning Later. “Yet somehow leaders think it makes sense to do the same with people.”

Honeywell’s reliance on furlough — combined with its commitment to customers, sustained long-term investment, and attention to supplier relations — helped it bounce back.

Research also backs up the hunch on which Mr Cote acted 12 years ago. A 2011 OECD review of 19 countries’ experience of short-time working confirmed such schemes preserved permanent workers’ jobs beyond recession. In a recent article for Harvard Business Review, Sandra Sucher and Shalene Gupta applaud US companies such as Tesla and Marriott for using furlough to soften the blow of this crisis. Such schemes let companies “maintain connections with their employees, cut costs while still providing employee benefits, and create a path to a seamless recovery”.

Yet defending the decision in 2008 was one of the toughest points of Mr Cote’s tenure as Honeywell’s boss.

Management, employees and investors were not “trained” to accept short-time working as a solution, he told me. Laws differed from country to country, and even state to state. In regions where furlough was put to a vote, support varied in line with the enthusiasm of managers for the measure. Elsewhere, while workers backed short-time working publicly, as Honeywell pushed through successive rounds of furlough, Mr Cote received private notes from staff urging him to “lay off 10 per cent of our people and have done with it”. As one FT reader commented when we asked recently about individuals’ experience of furlough: “Loneliness, anxiety, depression and guilt are hourly occurrences.”

“All recessions are different,” Mr Cote says, “but they all feel miserable.” He remains convinced, though, that irreversible job cuts would have undermined Honeywell’s ability to respond to an economic upturn, ultimately harming staff, investors and customers.

Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, has declared that “this is not a normal recession”. Mr Cote suggests, rather, that 80 per cent of the actions companies take to respond to recession are common across downturns, whether triggered by oil crises, inflation, terror attacks or mortgage mis-selling. To managers, he offers this advice: don’t panic; think independently; keep investing for the long term; communicate; and “whatever you do, let people know you’re sacrificing too”.

Some things, though, don’t change. “This is a brutal lay-off,” remarks Jack Nicholson’s smug anchorman, visiting the newsroom in Broadcast News, supposedly in solidarity with his colleagues. “You can make it a little less brutal by knocking a million dollars or so off your salary,” says his boss, before rapidly backtracking in the face of the trademark Nicholson glare.

From the videotapes to the workplace hugs, much of Broadcast News, the 1987 satire on media, looks old-fashioned. But when I watched the film again recently, as an escape from pandemic-provoked gloom, the scene where the network announces a round of redundancies seemed raw and relevant.

“If there’s anything I can do,” says the network director, relieved at how a veteran newsman has accepted the news of his forced early retirement. “Well, I certainly hope you die soon,” responds the departing colleague.

Similar scenes are playing out at companies around the world. Marks and Spencer, the retailer, Melrose, which owns venerable manufacturer GKN, New York-based Macy’s department store, and European aircraft-maker Airbus have all announced potential cuts in recent weeks. Manufacturing trade group Make UK has warned of a “jobs bloodbath”. Newsrooms have been particularly hard hit.

One added twist is that some of today’s lay-off conversations with unlucky staff will take place by video link rather than in person — easier for nervous managers, but crueller for the people they are laying off.

Another, more positive, development is that companies are becoming more creative as they brace for recession, turning to short-time working rather than lay-offs. As governments remove subsidies, what was a simple decision to hold staff in reserve, rather than fire them, will become more complicated. But avoiding permanent cuts makes sense, according to David Cote, former chief executive of Honeywell. The sheer cost of severance — in time, money and administrative hassle — mounts up. Often you have to hire the staff back to meet demand as the economy recovers.

“If someone told you that it would take you six months to build a factory, six months to recover your investment, you’ll get a return for six months, and then you’ll shut it down, you’d never go for it because it would be ridiculous,” he writes in his new book Winning Now, Winning Later. “Yet somehow leaders think it makes sense to do the same with people.”

Honeywell’s reliance on furlough — combined with its commitment to customers, sustained long-term investment, and attention to supplier relations — helped it bounce back.

Research also backs up the hunch on which Mr Cote acted 12 years ago. A 2011 OECD review of 19 countries’ experience of short-time working confirmed such schemes preserved permanent workers’ jobs beyond recession. In a recent article for Harvard Business Review, Sandra Sucher and Shalene Gupta applaud US companies such as Tesla and Marriott for using furlough to soften the blow of this crisis. Such schemes let companies “maintain connections with their employees, cut costs while still providing employee benefits, and create a path to a seamless recovery”.

Yet defending the decision in 2008 was one of the toughest points of Mr Cote’s tenure as Honeywell’s boss.

Management, employees and investors were not “trained” to accept short-time working as a solution, he told me. Laws differed from country to country, and even state to state. In regions where furlough was put to a vote, support varied in line with the enthusiasm of managers for the measure. Elsewhere, while workers backed short-time working publicly, as Honeywell pushed through successive rounds of furlough, Mr Cote received private notes from staff urging him to “lay off 10 per cent of our people and have done with it”. As one FT reader commented when we asked recently about individuals’ experience of furlough: “Loneliness, anxiety, depression and guilt are hourly occurrences.”

“All recessions are different,” Mr Cote says, “but they all feel miserable.” He remains convinced, though, that irreversible job cuts would have undermined Honeywell’s ability to respond to an economic upturn, ultimately harming staff, investors and customers.

Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, has declared that “this is not a normal recession”. Mr Cote suggests, rather, that 80 per cent of the actions companies take to respond to recession are common across downturns, whether triggered by oil crises, inflation, terror attacks or mortgage mis-selling. To managers, he offers this advice: don’t panic; think independently; keep investing for the long term; communicate; and “whatever you do, let people know you’re sacrificing too”.

Some things, though, don’t change. “This is a brutal lay-off,” remarks Jack Nicholson’s smug anchorman, visiting the newsroom in Broadcast News, supposedly in solidarity with his colleagues. “You can make it a little less brutal by knocking a million dollars or so off your salary,” says his boss, before rapidly backtracking in the face of the trademark Nicholson glare.

Monday, 3 April 2017

Sky-gods and scapegoats: From Genesis to 9/11 to Khalid Masood, how righteous blame of 'the other' shapes human history

Andy Martin in The Independent

God as depicted in Michelangelo's fresco ‘The Creation of the Heavenly Bodies’ in the Sistine Chapel Michelangelo

Here’s a thing I bet not too many people know. Where are the new BBC offices in New York? Some may know the old location – past that neoclassical main post office in Manhattan, not far from the Empire State Building, going down towards the Hudson on 8th Avenue. But now we have brand new offices, with lots of glass and mind-numbing security. And they can be found on Liberty Street, just across West Street from Ground Zero. The site, in other words, of what was the Twin Towers. And therefore of 9/11. I’m living in Harlem so I went all the way downtown on the “A” train the other day to have a conversation with Rory Sutherland in London, who is omniscient in matters of marketing and advertising.

Here’s a thing I bet not too many people know. Where are the new BBC offices in New York? Some may know the old location – past that neoclassical main post office in Manhattan, not far from the Empire State Building, going down towards the Hudson on 8th Avenue. But now we have brand new offices, with lots of glass and mind-numbing security. And they can be found on Liberty Street, just across West Street from Ground Zero. The site, in other words, of what was the Twin Towers. And therefore of 9/11. I’m living in Harlem so I went all the way downtown on the “A” train the other day to have a conversation with Rory Sutherland in London, who is omniscient in matters of marketing and advertising.

There were 19 hijackers involved in 9/11, where Ground Zero now marks the World Trade Centre, but only one person was involved in the Westminster attack (Rex)

I was reminded as I came out again and gazed up at the imposing mass of the Freedom Tower, the top of which vanished into the mist, that just the week before I was going across Westminster Bridge, in the direction of the Houses of Parliament. It struck me, thinking in terms of sheer numbers, that over 15 years and several wars later, we have scaled down the damage from 19 highly organised hijackers in the 2001 attacks on America to one quasi-lone wolf this month in Westminster. But that it is also going to be practically impossible to eliminate random out-of-the-blue attacks like this one.

But I also had the feeling, probably shared by most people who were alive but not directly caught up in either Westminster or the Twin Towers back in 2001: there but for the grace of God go I. That, I thought, could have been me: the “falling man” jumping out of the 100th floor or the woman leaping off the bridge into the Thames. In other words, I was identifying entirely with the victims. If I wandered over to the 9/11 memorial I knew that I could see several thousand names recorded there for posterity. Those who died.

But I also had the feeling, probably shared by most people who were alive but not directly caught up in either Westminster or the Twin Towers back in 2001: there but for the grace of God go I. That, I thought, could have been me: the “falling man” jumping out of the 100th floor or the woman leaping off the bridge into the Thames. In other words, I was identifying entirely with the victims. If I wandered over to the 9/11 memorial I knew that I could see several thousand names recorded there for posterity. Those who died.

So I am not surprised that nearly everything that has been written (in English) in the days since the Westminster killings has been similarly slanted. “We must stand together” and all that. But it occurs to me now that “we” (whoever that may be) need to make more of an effort to get into the mind of the perpetrators and see the world from their point of view. Because it isn’t that difficult. You don’t have to be a Quranic scholar. Khalid Masood wasn’t. He was born, after all, Adrian Elms, and brought up in Tunbridge Wells (where my parents lived towards the end of their lives). He was one of “us”.

This second-thoughts moment was inspired in part by having lunch with thriller writer Lee Child, creator of the immortal Jack Reacher. I wrote a whole book which was about looking over his shoulder while he wrote one of his books (Make Me). He said, “You had one good thing in your book.” “Really?” says I. “What was that then?” “It was that bit where you call me ‘an evil mastermind bastard’. That has made me think a bit.”

When he finally worked out what was going on in “Mother’s Rest”, his sinister small American town, and gave me the big reveal, I had to point out the obvious, namely that he, the author, was just as much the bad guys of his narrative as the hero. He was the one who had dreamed up this truly evil plot. No one else. Those “hog farmers”, who were in fact something a lot worse than hog farmers, were his invention. Lee Child was shocked. Because up until that point he had been going along with the assumption of all fans that he is in fact Jack Reacher. He saw himself as the hero of his own story.

There were 19 hijackers involved in 9/11, where Ground Zero now marks the World Trade Centre, but only one person was involved in the Westminster attack (PA)

I only mention this because it strikes me that this “we are the good guys” mentality is so widespread and yet not in the least justified. Probably the most powerful case for saying, from a New York point of view, that we are the good guys was provided by René Girard, a French philosopher who became a fixture at Stanford, on the West Coast (dying in 2015). His name came up in the conversation with Rory Sutherland because he was taken up by Silicon Valley marketing moguls on account of his theory of “mimetic desire”. All of our desires, Girard would say, are mediated. They are not autonomous, but learnt, acquired, “imitated”. Therefore, they can be manufactured or re-engineered or shifted in the direction of eg buying a new smartphone or whatever. It is the key to all marketing. But Girard also took the view, more controversially, that Christianity was superior to all other religions. More advanced. More sympathetic. Morally ahead of the field.

And he also explains why it is that religion and violence are so intimately related. I know the Dalai Lama doesn’t agree. He reckons that there is no such thing as a “Muslim terrorist” or a “Buddhist terrorist” because as soon as you take up violence you are abandoning the peaceful imperatives of religion. Which is all about tolerance and sweetness and light. Oh no it isn’t, says Girard, in Violence and the Sacred. Taking a long evolutionary and anthropological view, Girard argues that sacrifice has been formative in the development of homo sapiens. Specifically, the scapegoat. We – the majority – resolve our internal divisions and strife by picking on a sacrificial victim. She/he/it is thrown to the wolves in order to overcome conflict. Greater violence is averted by virtue of some smaller but significant act of violence. All hail the Almighty who therefore deigns to spare us further suffering.

In other words, human history is dominated by the scapegoat mentality. Here I have no argument with Girard. Least of all in the United States right now, where the Scapegoater-in-chief occupies the White House. But Girard goes on to argue that Christianity is superior because (a) it agrees with him that all history is about scapegoats and (b) it incorporates this insight into the Passion narrative itself. Jesus Christ was required to become a scapegoat and thereby save humankind. But by the same token Christianity is a critique of scapegoating and enables us to get beyond it. And Girard even neatly takes comfort from the anti-Christ philosopher Nietzsche, who denounced Christianity on account of it being too soft-hearted and sentimental. Cool argument. The only problem is that it’s completely wrong.

I’ve recently been reading Harold Bloom’s analysis of the Bible in The Shadow of a Great Rock. He reminds us, if we needed reminding, that the Yahweh of the Old Testament is a wrathful freak of arbitrariness. A monstrous and unpredictable kind of god, perhaps partly because he contains a whole bunch of other lesser gods that preceded him in Mesopotamian history. So naturally he gets particularly annoyed by talk of rival gods and threatens to do very bad things to anyone who worships Baal or whoever.

And he also explains why it is that religion and violence are so intimately related. I know the Dalai Lama doesn’t agree. He reckons that there is no such thing as a “Muslim terrorist” or a “Buddhist terrorist” because as soon as you take up violence you are abandoning the peaceful imperatives of religion. Which is all about tolerance and sweetness and light. Oh no it isn’t, says Girard, in Violence and the Sacred. Taking a long evolutionary and anthropological view, Girard argues that sacrifice has been formative in the development of homo sapiens. Specifically, the scapegoat. We – the majority – resolve our internal divisions and strife by picking on a sacrificial victim. She/he/it is thrown to the wolves in order to overcome conflict. Greater violence is averted by virtue of some smaller but significant act of violence. All hail the Almighty who therefore deigns to spare us further suffering.

In other words, human history is dominated by the scapegoat mentality. Here I have no argument with Girard. Least of all in the United States right now, where the Scapegoater-in-chief occupies the White House. But Girard goes on to argue that Christianity is superior because (a) it agrees with him that all history is about scapegoats and (b) it incorporates this insight into the Passion narrative itself. Jesus Christ was required to become a scapegoat and thereby save humankind. But by the same token Christianity is a critique of scapegoating and enables us to get beyond it. And Girard even neatly takes comfort from the anti-Christ philosopher Nietzsche, who denounced Christianity on account of it being too soft-hearted and sentimental. Cool argument. The only problem is that it’s completely wrong.

I’ve recently been reading Harold Bloom’s analysis of the Bible in The Shadow of a Great Rock. He reminds us, if we needed reminding, that the Yahweh of the Old Testament is a wrathful freak of arbitrariness. A monstrous and unpredictable kind of god, perhaps partly because he contains a whole bunch of other lesser gods that preceded him in Mesopotamian history. So naturally he gets particularly annoyed by talk of rival gods and threatens to do very bad things to anyone who worships Baal or whoever.

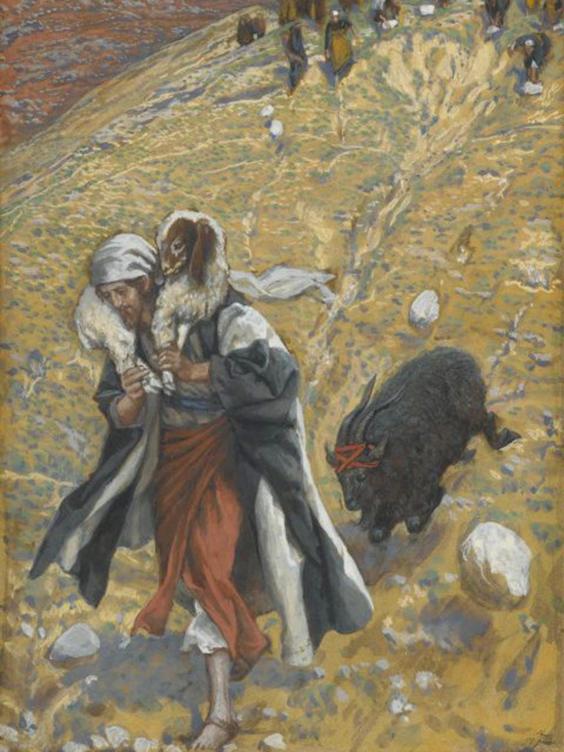

‘Agnus-Dei: The Scapegoat’ by James Tissot, painted between 1886 and 1894

Equally, if we fast forward to the very end of the Bible (ta biblia, the little books, all bundled together) we will find a lot of rabid talk about damnation and hellfire and apocalypse and the rapture and the Beast. If I remember right George Bush Jr was a great fan of the rapture, and possibly for all I know Tony Blair likewise, while they were on their knees praying together, and looked forward to the day when all true believers would be spirited off to heaven leaving the other deluded, benighted fools behind. Christianity ticks all the boxes of extreme craziness that put it right up there with the other patriarchal sky-god religions, Judaism and Islam.

But even if it were just the passion narrative, this is still a problem for the future of humankind because it suggests that scapegoating really works. It will save us from evil. “Us” being the operative word here. Because this is the argument that every “true” religion repeats over and over again, even when it appears to be saying (like the Dalai Lama) extremely nice and tolerant things: “we” are the just and the good and the saved, and “they” aren’t. There are believers and there are infidels. Insiders and outsiders (Frank Kermode makes this the crux of his study of Mark’s gospel, The Genesis of Secrecy, dedicated “To Those Outside”). Christianity never really got over the idea of the Chosen People and the Promised Land. Girard is only exemplifying and reiterating the Christian belief in their own (as the Americans used to say while annihilating the 500 nations) “manifest destiny”.

I find myself more on the side of Brigitte Bardot than René Girard. Once mythified by Roger Vadim in And God Created Woman, she is now unfairly caricatured as an Islamophobic fascist fellow-traveller. Whereas she would, I think, point out that, in terms of sacred texts, the problem begins right back in the book of Genesis, “in the beginning”, when God says “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth”. This “dominion” idea, of humans over every other entity, just like God over humans, and man over woman, is a stupid yet corrosive binary opposition that flies in the face of our whole evolutionary history.

This holier-than-thou attitude was best summed up for me in a little pamphlet a couple of besuited evangelists once put in my hand. It contained a cartoon of the world. This is what the world looks like (in their view): there are two cliffs, with a bottomless abyss between them. On the right-hand cliff we have a nice little family of well-dressed humans, man and wife and a couple of kids (all white by the way) standing outside their neat little house, with a gleaming car parked in the driveway. On the left-hand cliff we see a bunch of dumb animals, goats and sheep and cows mainly, gazing sheepishly across at the right-hand cliff, with a kind of awe and respect.

“We” are over here, “they” are over there. Us and them. “They are animals”. How many times have we heard that recently? It’s completely insane and yet a legitimate interpretation of the Bible. This is the real problem of the sky-god religions. It’s not that they are too transcendental; they are too humanist. Too anthropocentric. They just think too highly of human beings.

I’ve become an anti-humanist. I am not going to say “Je suis Charlie”. Or (least of all) “I am Khalid Masood“ either. I want to say: I am an animal. And not be ashamed of it. Which is why, when I die, I am not going to heaven. I want to be eaten by a bear. Or possibly wolves. Or creeping things that creepeth. Or even, who knows, if they are up for it, those poor old goats that we are always sacrificing.

But even if it were just the passion narrative, this is still a problem for the future of humankind because it suggests that scapegoating really works. It will save us from evil. “Us” being the operative word here. Because this is the argument that every “true” religion repeats over and over again, even when it appears to be saying (like the Dalai Lama) extremely nice and tolerant things: “we” are the just and the good and the saved, and “they” aren’t. There are believers and there are infidels. Insiders and outsiders (Frank Kermode makes this the crux of his study of Mark’s gospel, The Genesis of Secrecy, dedicated “To Those Outside”). Christianity never really got over the idea of the Chosen People and the Promised Land. Girard is only exemplifying and reiterating the Christian belief in their own (as the Americans used to say while annihilating the 500 nations) “manifest destiny”.

I find myself more on the side of Brigitte Bardot than René Girard. Once mythified by Roger Vadim in And God Created Woman, she is now unfairly caricatured as an Islamophobic fascist fellow-traveller. Whereas she would, I think, point out that, in terms of sacred texts, the problem begins right back in the book of Genesis, “in the beginning”, when God says “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth”. This “dominion” idea, of humans over every other entity, just like God over humans, and man over woman, is a stupid yet corrosive binary opposition that flies in the face of our whole evolutionary history.

This holier-than-thou attitude was best summed up for me in a little pamphlet a couple of besuited evangelists once put in my hand. It contained a cartoon of the world. This is what the world looks like (in their view): there are two cliffs, with a bottomless abyss between them. On the right-hand cliff we have a nice little family of well-dressed humans, man and wife and a couple of kids (all white by the way) standing outside their neat little house, with a gleaming car parked in the driveway. On the left-hand cliff we see a bunch of dumb animals, goats and sheep and cows mainly, gazing sheepishly across at the right-hand cliff, with a kind of awe and respect.

“We” are over here, “they” are over there. Us and them. “They are animals”. How many times have we heard that recently? It’s completely insane and yet a legitimate interpretation of the Bible. This is the real problem of the sky-god religions. It’s not that they are too transcendental; they are too humanist. Too anthropocentric. They just think too highly of human beings.

I’ve become an anti-humanist. I am not going to say “Je suis Charlie”. Or (least of all) “I am Khalid Masood“ either. I want to say: I am an animal. And not be ashamed of it. Which is why, when I die, I am not going to heaven. I want to be eaten by a bear. Or possibly wolves. Or creeping things that creepeth. Or even, who knows, if they are up for it, those poor old goats that we are always sacrificing.

Wednesday, 7 December 2016

India’s Demonetization Disaster

Shashi Tharoor in Project Syndicate

On November 8, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that, at the stroke of midnight, some 14 trillion rupees worth of 500- and 1,000-rupee notes – 86% of all the currency in circulation – would no longer be legal tender. With that, India’s economy was plunged into chaos.

Modi’s stated goal was to make good on his campaign pledge to fight “black money”: the illicit proceeds – often held as cash – of tax evasion, crime, and corruption. He also hoped to render worthless the counterfeit notes reportedly printed by Pakistan to fuel terrorism against India. Nearly a month later, however, all the demonetization drive has achieved is severe economic disruption. Far from being a masterstroke, Modi’s decision seems to have been a miscalculation of epic proportions.

The announcement immediately triggered a mad scramble to unload the expiring banknotes. Though people have until the end of the year to deposit the notes in bank accounts, doing so in large quantities could expose them to high taxes and fines. So they rushed to gas pumps, to jewelry shops, and to creditors to repay loans. Long queues snaked in, out, and around banks, foreign-exchange counters, and ATMs – anywhere where people might exchange the soon-to-be-defunct notes.

But, upon getting to the front of the line, people were often met with strict withdrawal limits, because, in a display of shocking ineptitude, not enough new currency was printed prior to the announcement. Worse, the new notes’ design prevents them from fitting into existing ATMs, and their denomination – 2,000 rupees – is too high to be useful for most people, especially given that the government’s failure to print enough smaller-denomination notes means that few can make change.

India’s previously booming economy has now ground to a halt. All indicators – sales, traders’ incomes, production, and employment – are down. Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh estimates that India’s GDP will shrink by 1-2% in the current fiscal year.

But, as is so often the case, the impact is not being felt equally by all. India’s wealthy, who are less reliant on cash and are more likely to hold credit cards, are relatively unaffected. The poor and the lower middle classes, however, rely on cash for their daily activities, and thus are the main victims of this supposedly “pro-poor” policy.

Small producers, lacking capital to stay afloat, are already shutting down. India’s huge number of daily wage workers can’t find employers with the cash to pay them. Local industries have suspended work for lack of money. The informal financial sector – which conducts 40% of India’s total lending, largely in rural areas – has all but collapsed.

India’s fishing industry, which depends on cash sales of freshly caught fish, is wrecked. Traders are losing perishable stocks. Farmers have been unloading produce below cost, because no one has the money to purchase it, and the winter crop could not be sown in time, because no one had cash for seeds.

Despite all of this, ordinary Indians have reacted with stoicism, seemingly willing to heed Modi’s call to be patient for 50 days, even though it could be much longer – anywhere between four months and a year – before the normal money supply is restored. The government’s assiduous public relations – which portrays people’s difficulties as a small sacrifice needed for the good of the country – seems to have done its job. “If our soldiers can stand for hours every day guarding our borders,” one popular social media meme asks, “why can’t we stand for a few hours in bank queues?”

But the sacrifice extends far beyond queues. Hospitals are turning away patients who have only old banknotes; families cannot buy food; and middle-class workers are unable to buy needed medicine. As many as 82 people have reportedly died in cash queues or related events. Furthermore, it seems likely that many of the short-term effects of the demonetization could persist – and intensify – in the longer term, with closed businesses unable to reopen. It could also cause lasting damage to India’s financial institutions, especially the Reserve Bank of India, whose reputation has already suffered.

Perhaps the worst part is that these sacrifices are not likely to achieve the government’s stated goal. Not all black money is in cash, and not all cash is black money. Those who held large quantities of black money seem to have found creative ways to launder it, rather than destroying it to avoid attracting the taxman’s attention, as the government expected. As a result, most of the black money believed to have been in circulation has now flooded into banks, depriving the government of its expected dividend.

On top of all of this, the government’s plan does nothing to control the source of black money. It will not be long before old habits – under-invoicing, fake purchase orders and bills, reporting of non-existent transactions, and blatant bribery – generates a new store of black money.

Many Modi supporters claim that the demonetization policy’s problems are a result of inept implementation. But the truth is that its design was fundamentally flawed. There was no “policy skeleton,” no cost-benefit analysis, and no evidence that alternative policy options were considered. Judging by the blizzard of policy tweaks since the announcement, it seems clear that no impact study was carried out.

Yet, rather than recognize the mounting risks of the non-transparent policy environment he has created, Modi has been discussing going even further, moving India to an entirely “cashless society.” Does he not know that more than 90% of financial transactions in India are conducted in cash, or that over 90% of retail outlets lack so much as a card reader? Is he unaware that over 85% of workers are paid in cash, and that more than half of the population is unbanked?

Modi came to power in 2014 promising to boost growth, create jobs for India’s youthful population, and encourage investment. His poorly conceived demonetization has made a mockery of these objectives, while bruising his reputation as an efficient and competent manager. How long it will take for India to recover is anyone’s guess.

On November 8, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that, at the stroke of midnight, some 14 trillion rupees worth of 500- and 1,000-rupee notes – 86% of all the currency in circulation – would no longer be legal tender. With that, India’s economy was plunged into chaos.

Modi’s stated goal was to make good on his campaign pledge to fight “black money”: the illicit proceeds – often held as cash – of tax evasion, crime, and corruption. He also hoped to render worthless the counterfeit notes reportedly printed by Pakistan to fuel terrorism against India. Nearly a month later, however, all the demonetization drive has achieved is severe economic disruption. Far from being a masterstroke, Modi’s decision seems to have been a miscalculation of epic proportions.

The announcement immediately triggered a mad scramble to unload the expiring banknotes. Though people have until the end of the year to deposit the notes in bank accounts, doing so in large quantities could expose them to high taxes and fines. So they rushed to gas pumps, to jewelry shops, and to creditors to repay loans. Long queues snaked in, out, and around banks, foreign-exchange counters, and ATMs – anywhere where people might exchange the soon-to-be-defunct notes.

But, upon getting to the front of the line, people were often met with strict withdrawal limits, because, in a display of shocking ineptitude, not enough new currency was printed prior to the announcement. Worse, the new notes’ design prevents them from fitting into existing ATMs, and their denomination – 2,000 rupees – is too high to be useful for most people, especially given that the government’s failure to print enough smaller-denomination notes means that few can make change.

India’s previously booming economy has now ground to a halt. All indicators – sales, traders’ incomes, production, and employment – are down. Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh estimates that India’s GDP will shrink by 1-2% in the current fiscal year.

But, as is so often the case, the impact is not being felt equally by all. India’s wealthy, who are less reliant on cash and are more likely to hold credit cards, are relatively unaffected. The poor and the lower middle classes, however, rely on cash for their daily activities, and thus are the main victims of this supposedly “pro-poor” policy.

Small producers, lacking capital to stay afloat, are already shutting down. India’s huge number of daily wage workers can’t find employers with the cash to pay them. Local industries have suspended work for lack of money. The informal financial sector – which conducts 40% of India’s total lending, largely in rural areas – has all but collapsed.

India’s fishing industry, which depends on cash sales of freshly caught fish, is wrecked. Traders are losing perishable stocks. Farmers have been unloading produce below cost, because no one has the money to purchase it, and the winter crop could not be sown in time, because no one had cash for seeds.

Despite all of this, ordinary Indians have reacted with stoicism, seemingly willing to heed Modi’s call to be patient for 50 days, even though it could be much longer – anywhere between four months and a year – before the normal money supply is restored. The government’s assiduous public relations – which portrays people’s difficulties as a small sacrifice needed for the good of the country – seems to have done its job. “If our soldiers can stand for hours every day guarding our borders,” one popular social media meme asks, “why can’t we stand for a few hours in bank queues?”

But the sacrifice extends far beyond queues. Hospitals are turning away patients who have only old banknotes; families cannot buy food; and middle-class workers are unable to buy needed medicine. As many as 82 people have reportedly died in cash queues or related events. Furthermore, it seems likely that many of the short-term effects of the demonetization could persist – and intensify – in the longer term, with closed businesses unable to reopen. It could also cause lasting damage to India’s financial institutions, especially the Reserve Bank of India, whose reputation has already suffered.

Perhaps the worst part is that these sacrifices are not likely to achieve the government’s stated goal. Not all black money is in cash, and not all cash is black money. Those who held large quantities of black money seem to have found creative ways to launder it, rather than destroying it to avoid attracting the taxman’s attention, as the government expected. As a result, most of the black money believed to have been in circulation has now flooded into banks, depriving the government of its expected dividend.

On top of all of this, the government’s plan does nothing to control the source of black money. It will not be long before old habits – under-invoicing, fake purchase orders and bills, reporting of non-existent transactions, and blatant bribery – generates a new store of black money.

Many Modi supporters claim that the demonetization policy’s problems are a result of inept implementation. But the truth is that its design was fundamentally flawed. There was no “policy skeleton,” no cost-benefit analysis, and no evidence that alternative policy options were considered. Judging by the blizzard of policy tweaks since the announcement, it seems clear that no impact study was carried out.

Yet, rather than recognize the mounting risks of the non-transparent policy environment he has created, Modi has been discussing going even further, moving India to an entirely “cashless society.” Does he not know that more than 90% of financial transactions in India are conducted in cash, or that over 90% of retail outlets lack so much as a card reader? Is he unaware that over 85% of workers are paid in cash, and that more than half of the population is unbanked?

Modi came to power in 2014 promising to boost growth, create jobs for India’s youthful population, and encourage investment. His poorly conceived demonetization has made a mockery of these objectives, while bruising his reputation as an efficient and competent manager. How long it will take for India to recover is anyone’s guess.

Sunday, 13 May 2012

Aamir Khan on Satyameva Jayate

Aamir Khan’s 13-episode Satyameva Jayate which

fuses together the mass appeal of celebrity with the mass reach of the

TV medium to raise awareness on social issues, is already the toast of

drawing rooms. But it has also sparked questions: do hi-glitz shows such

as this have a lasting impact? Or could this, like other shows, end up

being just another platform to peddle products? Aamir spoke to Namrata

Joshi in Jaipur. Excerpts:

Did you expect the programme would strike such a chord?

I was hoping it would be this huge. It has been a dream response.

Is the response due to the issue, the cause or the sheer power of your stardom?

No, it’s not about my stardom. Perhaps in a broad way people would come to the show thinking let’s see what he is saying. But it’s a combination of the research work of my team and the strength of TV which can, potentially, take change to every home. I am the via media in getting people to watch the show, to see the extraordinary stories of ordinary people.

Female foeticide (the topic of the first episode) has been much covered in the media. But Aamir Khan has got everyone talking about it now. Is the star turning into a citizen journalist here?

I am happy to be called a journalist. The first phase of our job, when we were dealing with research work I was a journalist. What I am doing here is empowering the viewers with 360 degree information on an issue. The information is emotional, social, legal, economic about the possible solutions and the way forward. Of course it is limited to my understanding of it. How my team and I, to the best of our ability, have understood various issues after two years of research.

But I get creative when it comes to taking that material to people. I am interested in reaching people on a human level. It's about what is the most effective way to touch your hearts. I am using entertainment to reach out. Which is not to say I am using fun and games. It's more about underlining things with emotions. Like I did with the issue of childcare and education in a film like Taare Zameen Par. The information people get from a newspaper and magazine article doesn't change their heart. Very few people cry on reading newspapers. I try to affect them emotionally.

The show has been criticised by some for being too manipulative...

I am using honest emotions to say something good. Look at the manner in which I open the show. I talk about mothers and motherhood. Then go on to pick one mother to show how we treat our mothers. I don't say the word foeticide immediately at the start of the show but after two cases have been discussed. I gradually take you to the issue. I am a communicator. I scare you with its eventualities when I talk of women being bought and sold. I am not limited by the format of an article. I am on a general entertainment channel. I am a person who makes feature films. These are my skillsets and I am using them to deal with the issues. Am good at engaging with people emotionally. That's what I have a passion for and am good at and I am using that ability.

Do such shows bring about change? Or do people engage and move on?

Often the stance on any problem is why doesn't the police, the government do something about it. However, here I am asking people to do what I am doing myself which is to look within and ask what am I doing about it. It's not about physical action but an internal, personal journey. The biggest change we can bring about is in ourselves. I am not asking people to come on the roads and take out a dharna. Three crore female foetuses have been aborted in the last 30-40 years. Female foeticide is a crime planned in our bedrooms and we can't have cops in the bedrooms to monitor us. But if we get even a hint that something like this is being planned in our family or by our friends we can create a ruckus. I won't tell you to decide. I won't judge you if you don't do anything. The choice has to be yours, I can't force it on you. I hope people do find courage and desire to change. So if a doctor who has been involved in foeticides decides after seeing the show that he or she won't do it anymore bas mera kaam ho gaya. Even if one girl child is saved then the show is a success.

I will be on TV. I will also be on Vividh Bharati, AIR, Radio Mirchi, Star News. I will write a column in HT. With every issue I want to go wide on many platforms. It's a deep and concentrated approach to reach out in as many different ways as possible. I hope it will make people understand an issue for a life. I hope it will have them converted for life.

People are critical of the way you get involved with a cause and then get out. For instance, the Narmada protest, which you joined briefly.

I find it a very faulty critique. It's actually your desire of seeing me as a full time, 24X7 social activist. I am not that. It's not what I claim to be. I can agree, support, endorse but I can't leave my job which is films. Talaash is delayed right now. But I will go back to it. Am doing Dhoom 3 and P.K. next. But I will continue to support causes while doing my work. I can't measure up to the 500% expectations that you have of me. I am consistent with what I am committing myself to. It's like I have just said that I will come and have tea with you but it's you who are assuming that I am going to come and live with you for life. If my involvement with an issue seems less to you then why don't you do the good work?

You can question me two months hence that you had done a show on this issue and why don't you remain with it your entire life. According to me it's for the state and administration to take forward the job. You, as an individual, also need to take a call, be responsible and decisive.

There are whispers about your charging Rs 3 crore per episode for a show on serious social issues...

I never discuss my fee. But since you asked I am getting Rs 3.5 crore per episode. Firstly what I get is none of anyone's business. Main apni mehnat ki kama aur khaa raha hoon. [I am earning and enjoying the benefits of my hard-work]. I am not doing anything wrong. Main izzat se, achchaa kaam karke roti kama raha hoon aur mujhe fakr hai is baat ka [I am honourably, by doing good work, earning my bread, and I am proud of it]. Secondly to clear the misconception this amount includes the cost of the episode also. The bulk of the money goes into the cost and some of the episodes may have overshot the amount. Thirdly, I have endorsements deals of about Rs 100-125 crore per year. I have stopped them for a year while the show is on. There's no logic in the decision, it's purely emotional. But tell me who has ever said no to Rs 100 crore for a cause?

So what issues do we see next?

We started off with 20 topics of which we fleshed out 16 and eventually locked in 13. These are topics which affect every Indian. But the topic of next week will not be revealed in advance. Even when I start the episode you wouldn't know immediately. It's not just the topic that's important but also on how I present it and get you engaged and involved with it.

Will you discuss contentious political topics like Gujarat, Kashmir, North East?

The issues will be social more than political. At this point I want to concentrate only on social issues. But it's impossible to cut away political aspects from any issue. Also if we bring about change in the people and their perceptions our political processes will also change over time.

You'll see all kinds of India: the India I have seen. There are heart-breaking and traumatic stories, inspiring stories of great courage and high values and ideals.

Do we see you taking to politics like stars abroad?

I have always been categorical about my no to politics. Political alignments, party affiliations I am not interested in.

--------

Did you expect the programme would strike such a chord?

I was hoping it would be this huge. It has been a dream response.

Is the response due to the issue, the cause or the sheer power of your stardom?

No, it’s not about my stardom. Perhaps in a broad way people would come to the show thinking let’s see what he is saying. But it’s a combination of the research work of my team and the strength of TV which can, potentially, take change to every home. I am the via media in getting people to watch the show, to see the extraordinary stories of ordinary people.

Female foeticide (the topic of the first episode) has been much covered in the media. But Aamir Khan has got everyone talking about it now. Is the star turning into a citizen journalist here?

I am happy to be called a journalist. The first phase of our job, when we were dealing with research work I was a journalist. What I am doing here is empowering the viewers with 360 degree information on an issue. The information is emotional, social, legal, economic about the possible solutions and the way forward. Of course it is limited to my understanding of it. How my team and I, to the best of our ability, have understood various issues after two years of research.

But I get creative when it comes to taking that material to people. I am interested in reaching people on a human level. It's about what is the most effective way to touch your hearts. I am using entertainment to reach out. Which is not to say I am using fun and games. It's more about underlining things with emotions. Like I did with the issue of childcare and education in a film like Taare Zameen Par. The information people get from a newspaper and magazine article doesn't change their heart. Very few people cry on reading newspapers. I try to affect them emotionally.

The show has been criticised by some for being too manipulative...

I am using honest emotions to say something good. Look at the manner in which I open the show. I talk about mothers and motherhood. Then go on to pick one mother to show how we treat our mothers. I don't say the word foeticide immediately at the start of the show but after two cases have been discussed. I gradually take you to the issue. I am a communicator. I scare you with its eventualities when I talk of women being bought and sold. I am not limited by the format of an article. I am on a general entertainment channel. I am a person who makes feature films. These are my skillsets and I am using them to deal with the issues. Am good at engaging with people emotionally. That's what I have a passion for and am good at and I am using that ability.

Do such shows bring about change? Or do people engage and move on?

Often the stance on any problem is why doesn't the police, the government do something about it. However, here I am asking people to do what I am doing myself which is to look within and ask what am I doing about it. It's not about physical action but an internal, personal journey. The biggest change we can bring about is in ourselves. I am not asking people to come on the roads and take out a dharna. Three crore female foetuses have been aborted in the last 30-40 years. Female foeticide is a crime planned in our bedrooms and we can't have cops in the bedrooms to monitor us. But if we get even a hint that something like this is being planned in our family or by our friends we can create a ruckus. I won't tell you to decide. I won't judge you if you don't do anything. The choice has to be yours, I can't force it on you. I hope people do find courage and desire to change. So if a doctor who has been involved in foeticides decides after seeing the show that he or she won't do it anymore bas mera kaam ho gaya. Even if one girl child is saved then the show is a success.

I will be on TV. I will also be on Vividh Bharati, AIR, Radio Mirchi, Star News. I will write a column in HT. With every issue I want to go wide on many platforms. It's a deep and concentrated approach to reach out in as many different ways as possible. I hope it will make people understand an issue for a life. I hope it will have them converted for life.

People are critical of the way you get involved with a cause and then get out. For instance, the Narmada protest, which you joined briefly.

I find it a very faulty critique. It's actually your desire of seeing me as a full time, 24X7 social activist. I am not that. It's not what I claim to be. I can agree, support, endorse but I can't leave my job which is films. Talaash is delayed right now. But I will go back to it. Am doing Dhoom 3 and P.K. next. But I will continue to support causes while doing my work. I can't measure up to the 500% expectations that you have of me. I am consistent with what I am committing myself to. It's like I have just said that I will come and have tea with you but it's you who are assuming that I am going to come and live with you for life. If my involvement with an issue seems less to you then why don't you do the good work?

You can question me two months hence that you had done a show on this issue and why don't you remain with it your entire life. According to me it's for the state and administration to take forward the job. You, as an individual, also need to take a call, be responsible and decisive.

There are whispers about your charging Rs 3 crore per episode for a show on serious social issues...

I never discuss my fee. But since you asked I am getting Rs 3.5 crore per episode. Firstly what I get is none of anyone's business. Main apni mehnat ki kama aur khaa raha hoon. [I am earning and enjoying the benefits of my hard-work]. I am not doing anything wrong. Main izzat se, achchaa kaam karke roti kama raha hoon aur mujhe fakr hai is baat ka [I am honourably, by doing good work, earning my bread, and I am proud of it]. Secondly to clear the misconception this amount includes the cost of the episode also. The bulk of the money goes into the cost and some of the episodes may have overshot the amount. Thirdly, I have endorsements deals of about Rs 100-125 crore per year. I have stopped them for a year while the show is on. There's no logic in the decision, it's purely emotional. But tell me who has ever said no to Rs 100 crore for a cause?

So what issues do we see next?

We started off with 20 topics of which we fleshed out 16 and eventually locked in 13. These are topics which affect every Indian. But the topic of next week will not be revealed in advance. Even when I start the episode you wouldn't know immediately. It's not just the topic that's important but also on how I present it and get you engaged and involved with it.

Will you discuss contentious political topics like Gujarat, Kashmir, North East?

The issues will be social more than political. At this point I want to concentrate only on social issues. But it's impossible to cut away political aspects from any issue. Also if we bring about change in the people and their perceptions our political processes will also change over time.

You'll see all kinds of India: the India I have seen. There are heart-breaking and traumatic stories, inspiring stories of great courage and high values and ideals.

Do we see you taking to politics like stars abroad?

I have always been categorical about my no to politics. Political alignments, party affiliations I am not interested in.

--------

Jump cut - His Star Grounded

He was not aspiring to be Balraj Sahni. He was a superstar and he wanted to be accorded his rightful place.

Bishwadeep Moitra

The

summer of 2007 brought me a rather unusual invitation. Unusual, because

the round table conference in Florida that I was invited to participate

in—pompously called the Leadership Project—had little in common with my

vocation. But the real hook for me was the opportunity to meet Aamir

Khan, who too had been invited—and had consented to come.

Aamir came across like the character he had played in Dil Chahta Hai, charmingly unassuming. He took his wife Kiran Rao’s environmental concerns seriously. When she objected to the engine of our monstrous safari jeep idling every time we stopped for a sighting in the 7,400-acre Wild Oak park, Aamir dutifully went up to the driver and asked him to switch the engine off.

Finally, after doing our bit to save the world in three sessions, we had some time to luxuriate at the sprawling facility. All of us had been allotted chalets to be shared with a fellow delegate. Aamir and Kiran, of course, had been given a chalet of their own, complete with a swimming pool and a sauna. They very generously invited some of us to hang out in their chalet. And what an afternoon it turned out to be.

Aamir’s entourage consisted of a three-member personal staff. A bodyguard who doubled as a physical trainer, another who did his suitcases, and a third who was his feeder (read on). Aamir was about to shoot for Ghajini and had to look big and brawny. Mr Feeder’s job was to make sure Aamir followed the dietary regimen. Every hour, he would bring an egg yolk balanced precariously on a spoon to pour into Aamir’s mouth. This, a rather strange ritual, went about in a very matter-of-fact way.

All evening, Aamir regaled us with anecdotes about the co-stars, producers, directors he had worked with, and his family with great candour. He told us that when Tahir Hussain (Aamir’s producer-father) offered Jeetendra a double-role, Jumping Jack quipped: “Mujhse ek role ki acting to hoti nahin hai, double role kaise karoonga!” He said he watched few films, but read a lot. He didn’t think much of Sholay or any other film—save his own.

Our adda eventually thinned out and I could feel the star becoming more at ease. But I could also sense a rancour. Aamir could not hide his disappointment that he was still not regarded like a Amitabh Bachchan or a Dilip Kumar despite two decades of stardom and a dozen runaway hits. Ghajini, Taare Zameen Par and 3 Idiots had not yet happened; another Khan was King.

Aamir felt Shahrukh Khan managed the media very well, giving the impression that SRK’s movies were all superhits. He rattled off box-office figures to prove that all of his movies had fared better than SRK’s. The Aamir Khan I was now chatting with had shades of Satyajit Ray’s protagonist Arindam Mukherjee, played by Uttam Kumar, in Nayak. A superstar at the helm of stardom, struggling to be at peace with himself.

I then advance a meek defence, saying, “Outlook has put you on its cover twice.” To which Aamir charged, “But India Today had me on its cover three times.” I said, “Look Aamir, the dignity and gravitas you bring with the characters you play and the high probity you display in public life makes you the modern-day Balraj Sahni, a fine actor and an exemplary citizen.”

The moment he heard the B-word, Aamir’s expression changed from an accommodative amiability to a grim grey.

By way of placation, I attempted another salvo. “When Amitabh Bachchan, hailing from a literary family, wanted to join the debauched film industry, his first director in Saat Hindustani, K.A. Abbas, cited Balraj Sahni to AB’s father Harivanshrai: ‘An industry with which a man like Balraj Sahni could associate himself, your son too should be able to survive honourably’,” I said.

Aamir saw red. He was not aspiring to be Balraj Sahni. He was a superstar and he wanted to be accorded his rightful place. Saat saal baad, surely he has got it?

Bishwadeep Moitra is executive editor, Outlook

Aamir came across like the character he had played in Dil Chahta Hai, charmingly unassuming. He took his wife Kiran Rao’s environmental concerns seriously. When she objected to the engine of our monstrous safari jeep idling every time we stopped for a sighting in the 7,400-acre Wild Oak park, Aamir dutifully went up to the driver and asked him to switch the engine off.

Finally, after doing our bit to save the world in three sessions, we had some time to luxuriate at the sprawling facility. All of us had been allotted chalets to be shared with a fellow delegate. Aamir and Kiran, of course, had been given a chalet of their own, complete with a swimming pool and a sauna. They very generously invited some of us to hang out in their chalet. And what an afternoon it turned out to be.

Aamir’s entourage consisted of a three-member personal staff. A bodyguard who doubled as a physical trainer, another who did his suitcases, and a third who was his feeder (read on). Aamir was about to shoot for Ghajini and had to look big and brawny. Mr Feeder’s job was to make sure Aamir followed the dietary regimen. Every hour, he would bring an egg yolk balanced precariously on a spoon to pour into Aamir’s mouth. This, a rather strange ritual, went about in a very matter-of-fact way.

All evening, Aamir regaled us with anecdotes about the co-stars, producers, directors he had worked with, and his family with great candour. He told us that when Tahir Hussain (Aamir’s producer-father) offered Jeetendra a double-role, Jumping Jack quipped: “Mujhse ek role ki acting to hoti nahin hai, double role kaise karoonga!” He said he watched few films, but read a lot. He didn’t think much of Sholay or any other film—save his own.

Our adda eventually thinned out and I could feel the star becoming more at ease. But I could also sense a rancour. Aamir could not hide his disappointment that he was still not regarded like a Amitabh Bachchan or a Dilip Kumar despite two decades of stardom and a dozen runaway hits. Ghajini, Taare Zameen Par and 3 Idiots had not yet happened; another Khan was King.

Aamir felt Shahrukh Khan managed the media very well, giving the impression that SRK’s movies were all superhits. He rattled off box-office figures to prove that all of his movies had fared better than SRK’s. The Aamir Khan I was now chatting with had shades of Satyajit Ray’s protagonist Arindam Mukherjee, played by Uttam Kumar, in Nayak. A superstar at the helm of stardom, struggling to be at peace with himself.

I then advance a meek defence, saying, “Outlook has put you on its cover twice.” To which Aamir charged, “But India Today had me on its cover three times.” I said, “Look Aamir, the dignity and gravitas you bring with the characters you play and the high probity you display in public life makes you the modern-day Balraj Sahni, a fine actor and an exemplary citizen.”

The moment he heard the B-word, Aamir’s expression changed from an accommodative amiability to a grim grey.

By way of placation, I attempted another salvo. “When Amitabh Bachchan, hailing from a literary family, wanted to join the debauched film industry, his first director in Saat Hindustani, K.A. Abbas, cited Balraj Sahni to AB’s father Harivanshrai: ‘An industry with which a man like Balraj Sahni could associate himself, your son too should be able to survive honourably’,” I said.

Aamir saw red. He was not aspiring to be Balraj Sahni. He was a superstar and he wanted to be accorded his rightful place. Saat saal baad, surely he has got it?

Bishwadeep Moitra is executive editor, Outlook

Sunday, 5 February 2012

An Ode to India's Batting Triumvirate

Show me a hero, wrote novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald, and I will write you a tragedy. Sporting heroes come pre-loaded with the tragedy gene. A Muhammad Ali who goes one fight too far, a Kapil Dev who is carried around till he breaks a record, a Michael Schumacher who returns to the scenes of his triumphs but as an also-ran—sport is cruel. The sportsman’s dilemma is simply stated: should he retire when the performances sag or give it one last shot so he can go out on a high? At either end of the performance scale, the temptation is to carry on—either to prove yourself worthy, or to establish there is life in the old dog yet.

Australia’s Ricky Ponting was on the verge of being dropped when he made a century and then a double against India, and must be wondering now how far he ought to push. His inspiration to continue playing, Sachin Tendulkar and Rahul Dravid, are probably wondering too. They have had phases before when nothing went right, but it was business as usual soon enough.

Last year, Dravid made more runs than anybody else in world cricket; the previous year, that record belonged to Tendulkar. Great sportsmen hate to go gentle into that good night; they, like fans on their behalf, rage against the dying of the light. For over a decade-and-a-half, these two, V.V.S. Laxman and the oldest of the group, Sourav Ganguly, gave India their best batting line-up, their greatest victories and their top ranking in world cricket.

Tendulkar made his debut in the same year as the Berlin Wall fell; Nelson Mandela was still in jail, and Mike Tyson was the world heavyweight champion. Now pieces of the Berlin Wall decorate homes of tourists who have visited the site, Mandela has graduated from being a president to a concept, and no one knows who the heavyweight champion is. But Tendulkar plays on, a boyish eminence grise in a country whose average age is nearly the number of years he has been an international cricketer.

Pundits have been calling for the heads of the champions, but what is startling is the reaction of the average fan. That no effigies were burnt and no players’ houses stoned after the Australia tour suggests a level of indifference that is painful to behold.

Clearly, we are in the mourning period; in sport, mourning sometimes precedes the end. But mourning can also be a period of celebration. These cricketers have meant something special to a nation shaking free the coils of mediocrity in so many fields and emerging self-confident and ready to take on the world on its own terms.

At 18, V.V.S. Laxman decided to give himself four years to make it as a cricketer; plan B was a career in medicine, the profession of his parents and many relatives. At 22, Rahul Dravid told a friend, “I do not want to be just another Test cricketer; I want to be bracketed with Sunil Gavaskar and G.R. Vishwanath.” Sachin Tendulkar was 17 when he responded to the standard query on the distractions of big money thus: “I will never forget that it is my success on the field that is the cause of the riches off it.”

How distant the 1990s seem now. A new India was dawning. A feted finance minister breathed life into the vision of a prime minister whose version of glasnost and perestroika was filed under the less romantic label of “market reforms”. Politicians tend to make poor poster boys of their own reforms. Happily, Tendulkar presented himself as the candidate.

It all seems ordained now, but that is only time imposing order and meaning to events. Tendulkar had everything—he was a Test cricketer at 16, and by 19 had made centuries in both England and Australia. He was so obviously mama’s boy—the manager on his first tour of England, Bishan Bedi, spoke of how all the older women wanted to mother him and the younger ones seduce him—and patently non-controversial. And he had the best straight drive in the business; and in the early days a fierce way of handling the short-pitched delivery that reduced those fielding on the leg side boundary to mere ball boys and collectors of the cricket ball from the crowd.

Received wisdom is that India’s climb to the top of the rankings began with that epic Calcutta Test against Steve Waugh’s Australians, who had won their previous 16 Tests in a row. Laxman’s 281 and the 376-run partnership with Dravid ensured India won the match after following on.

The more likely candidate for the turnaround is the Headingley Test of 2002. India won the toss on a seaming track made-to-order for the England bowlers. Nine times out of ten, they would have, as a defensive measure, fielded first on winning the toss. But this was a new India and new captain Ganguly decided to bat. India played two spinners and didn’t pick opener S.S. Das who had made 250 against Essex in their previous match, preferring Sanjay Bangar for his medium pace bowling and adhesive batting.

It worked. India made over 600, with centuries from Tendulkar, Dravid and Ganguly, and won by an innings. It was reward for boldness, imagination and supreme self-confidence.

For a decade and more, that middle order (now strengthened by the arrival at the top of Virender Sehwag) planted the Indian flag on grounds all over the world—at Leeds and Adelaide, Multan and Harare, Kingston, Johannesburg, Nottingham, Perth, Galle and Colombo.

Individual records came as byproducts of team efforts. Tendulkar’s driving on either side of the wicket was sheer joy. As a 16-year-old, he attacked the leg spinner Abdul Qadir, hitting him for 27 runs in an over. It wasn’t an official international, but it brought together the batsman’s impetuosity and creativity in one nice packet. He was actually beaten in flight once, but trusted his instinct and his forearms to hit high into the crowd.

Where were you when Tendulkar made his Test debut? In India, opposition parties were coming together under the banner of the National Front and projecting V.P. Singh as the “clean” alternative to prime minister Rajiv Gandhi. V.P. Singh took charge while the Indian team was in Pakistan, and Tendulkar was taking his first steps towards cricketing immortality. Those not yet born when Tendulkar made his debut are well over the voting age now.

For one, it is entirely possible that Indian cricket itself might have taken a long time to recover from the match-fixing allegations a decade ago. Skipper Mohammed Azharuddin confessed to having manipulated results and without the obvious integrity of men like Dravid and Laxman, and those who have retired like Ganguly, Anil Kumble, Javagal Srinath and Venkatesh Prasad, the game might have been destroyed.

Significantly, these batsmen brought to the game an Indianness, the inherited technique and uniqueness of a nation that is sometimes reduced to the cliche, ‘oriental magic’. You can bowl to Laxman anywhere you want, and he will use his wrists to send it between fielders on either side of the wicket. There is no apparent effort, only the most elegant of bat swings, visually all curves and gentle arcs. Laxman’s bat makes no angles to the wind.

Dravid, the man who chose to “walk” when on 95 on his debut at Lord’s, formed a wonderful relationship with Laxman. They have taken over 300 catches between them at slips, and they relax, as Dravid explained, “by talking about our families, the plumbers and carpenters when we were building houses and so on”. When you saw a serious look on the ever smiling face of vvs at slip, it was probably because he had just realised that plumbers in Hyderabad charged more than those in Bangalore. It didn’t matter. What mattered was the camaraderie, and the fact that nearly every catch was taken.

These three players have played 118 Tests with each other. For Tendulkar and Dravid, make that 146. That’s nearly two years in number of days, and if you add the one-day matches, the travel, practice days and camps to that, that’s more days spent in each other’s company than many couples stay married.

Dravid has scored more runs for India than Tendulkar in the same period, a statistic that is not widely known or appreciated. One of the great sights in recent years has been his authoritative square cut or the pull that brooked no response, played while his helmet dripped honest sweat over a long innings. Year after year, we believed when he was batting that god was in his heaven and all was right with the world.

In their growing years, players make huge sacrifices, leading an almost monastic life, the focus on the game and nothing else. By the late 30s, when other professionals—the accountants and managers who do not cause a nation to stand up and demand their resignation—are looking to settle down, the life of a sportsman is over. Your brief career is done, but you have a lot of life left. How do you cope if you are not into the media or coaching or the cauldron of politics known as cricket administration? Especially since cricket is all you know. At 30, Tendulkar was asked what his favourite book was, and he answered with child-like charm, “I haven’t started reading yet.”

The players may not fully understand their future yet; but ironically, we do not fully understand their present (or past) either. The Owl of Minerva, wrote Hegel, “spreads its wings only with the falling of dusk”. We understand a historical condition just as it passes away. In the next couple of years, as we come to a greater understanding of what Tendulkar and company meant to us, let us not regret anything crass in the manner their twilight years were handled. Indianness and integrity have been important aspects of the cricket of the threesome. Indian cricket needs to handle such stalwarts with dignity and maturity.

There is a sense that an Indian team will change from being an old-fashioned one (in terms of behaviour, “old-fashioned” is a compliment) into a modern, unimaginative one where joy, sorrow, exasperation, irritation, ecstasy, sense of achievement, aggression, love and all emotions are expressed with a four-letter word or its many Indian versions involving close relatives. Virat Kohli is a superb batsman and a future India captain, but his response on getting to a century in Adelaide was juvenile. The Kohlis and others like him need to learn from the earlier generation about self-respect and respecting the game itself.

Not that the older lot have been pussycats, rolling over to be tickled. Initially, Dravid’s shyness was mistaken for weakness, but not after he responded to an Allan Donald taunt in the course of his first century in South Africa. The Bangalore boy told the fastest bowler in the world to assume an impossible anatomical posture, not in those words exactly, but in a crisp, short phrase.

The message went home not only to that bowler but to all bowlers around the world. No one tried riling either Dravid or the other two again.

Indian cricket may be at the crossroads; the retirement of the great players will see the end of a civilisation as we know it. But the Tendulkars, Dravids and Laxmans—seen by many as part of the problem now—can easily be part of the solution. India’s next series outside the subcontinent is in Zimbabwe in July 2013. Then come the series in SA and New Zealand. Time enough to rebuild.

Not so long ago, we used to canonise our heroes. The modern method is to spit at them. Our great players deserve better.

(Suresh Menon is editor, Wisden India Almanack, and author of Bishan: The Portrait of a Cricketer.)

Wednesday, 7 December 2011

NIMBY - the death of altruism

With little but economic gloom on the horizon, David Cameron likes to

appeal to Britain's better instincts, insisting: "We're all in this

together." Whether the average citizen is listening to the Prime

Minister's entreaties is open to doubt: Britons appear to be more

selfish and less interested in the common good than ever before.

The latest British Social Attitudes report suggests that levels of

altruism are falling in these straitened times. People are hostile to

housebuilding in their neighbourhoods, less likely to make personal

sacrifices to protect the environment and increasingly resistant to

paying more for hospitals and schools.

They are also sceptical about the Government's ability to change things for the better, with a growing belief that is down to individuals to sort out their problems for themselves. Support for tax rises to boost spending on services such as health and education has fallen to 31 per cent – half of the 63 per cent of people in favour just nine years ago.

The number willing to pay higher prices to safeguard the environment, such as by buying Fair Trade goods, has fallen from 43 per cent in 2001 to 26 per cent today, while the proportion prepared to pay more tax for the same reason is down from 31 per cent to 22 per cent.

Researchers also uncovered evidence of an entrenched "not in my backyard" mentality over housebuilding, with 45 per cent of people opposing any new development near them, compared with 30 per cent in favour. Opposition is strongest in areas where property is in shortest supply – 58 per cent in outer London and 50 per cent in the South-east of England.

The survey, now in its 29th year, acknowledged that three-quarters of the public believe the income gap between rich and poor is too large. Yet only 35 per cent believe the Coalition should redistribute more to lessen the disparity.

Paradoxically, 54 per cent of the public believe jobless benefits are too high and discourage the unemployed from finding work, up from 35 per cent in 1983, the first year of the survey. And although people were concerned about child poverty levels, 63 per cent pinned some of the blame for the problem on parents who "don't want to work".

The survey, by the independent social research institute NatCen, found Britons increasingly relaxed about private healthcare. In 1999, 38 per cent said it was wrong; today the figure has fallen to 24 per cent.

45 Percentage of Britons who oppose any new development near their homes. In outer London the figure is 58 per cent.

26 Percentage of people willing to pay more for ethical goods to save the environment – down from 43 per cent 10 years ago.

They are also sceptical about the Government's ability to change things for the better, with a growing belief that is down to individuals to sort out their problems for themselves. Support for tax rises to boost spending on services such as health and education has fallen to 31 per cent – half of the 63 per cent of people in favour just nine years ago.

The number willing to pay higher prices to safeguard the environment, such as by buying Fair Trade goods, has fallen from 43 per cent in 2001 to 26 per cent today, while the proportion prepared to pay more tax for the same reason is down from 31 per cent to 22 per cent.

Researchers also uncovered evidence of an entrenched "not in my backyard" mentality over housebuilding, with 45 per cent of people opposing any new development near them, compared with 30 per cent in favour. Opposition is strongest in areas where property is in shortest supply – 58 per cent in outer London and 50 per cent in the South-east of England.

The survey, now in its 29th year, acknowledged that three-quarters of the public believe the income gap between rich and poor is too large. Yet only 35 per cent believe the Coalition should redistribute more to lessen the disparity.

Paradoxically, 54 per cent of the public believe jobless benefits are too high and discourage the unemployed from finding work, up from 35 per cent in 1983, the first year of the survey. And although people were concerned about child poverty levels, 63 per cent pinned some of the blame for the problem on parents who "don't want to work".