'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label ban. Show all posts

Showing posts with label ban. Show all posts

Saturday, 11 May 2024

Monday, 24 May 2021

Sunday, 5 February 2017

Wednesday, 28 October 2015

Why are drugs illegal?

‘To enable Harry Anslinger to keep his army of drug enforcers [the Untouchables], he created a new drug threat, cannabis, which he called marijuana to make it sound more Mexican.’ Photograph: Tomas Rodriguez/Corbis

David Nutt in The Guardian

This is, of course, a flawed question but one that illustrates a major paradox in the UK and international laws on drugs. Some drugs – such as alcohol, caffeine and nicotine – are legal, whereas others – such as cannabis, cocaine and opium – are not. This has not always been the case.

In the 19th century extracts of these three now-illegal drugs were legal in the UK, and were sold in pharmacies and even corner shops. Queen Victoria’s physician was a great proponent of the value of tincture of cannabis and the monarch is reputed to have used it to counteract the pain of menstrual periods and childbirth. Now it is denied to people with severe enduring spasticity and pain from neurological disorders and cancer. Why?

David Nutt in The Guardian

This is, of course, a flawed question but one that illustrates a major paradox in the UK and international laws on drugs. Some drugs – such as alcohol, caffeine and nicotine – are legal, whereas others – such as cannabis, cocaine and opium – are not. This has not always been the case.

In the 19th century extracts of these three now-illegal drugs were legal in the UK, and were sold in pharmacies and even corner shops. Queen Victoria’s physician was a great proponent of the value of tincture of cannabis and the monarch is reputed to have used it to counteract the pain of menstrual periods and childbirth. Now it is denied to people with severe enduring spasticity and pain from neurological disorders and cancer. Why?

Activists to get high together in protest against psychoactive substances ban

The truth is unpalatable and goes back to the period of alcohol prohibition in the US in the 1920s. This was introduced as a harm-reduction measure because alcohol was seen (correctly) as a drug that seriously damaged families and children. But public demand for alcohol in the US did not abate and this fuelled a massive rise in bootleg alcohol and underground bars (known as speakeasys) that encouraged the rise of the mafia and other crime syndicates.

To combat this, the US government set up a special army of enforcers, under the command of Harry Anslinger, which became known as “the untouchables”. This army of enforcers was widely celebrated by the newspapers and the acclaim propelled Anslinger to national prominence. However, when public disquiet at the crime and social damage caused by alcohol prohibition led to its repeal, Anslinger saw his position as being in danger.

To enable him to keep his army of drug enforcers, he created a new drug threat: cannabis, which he called marijuana to make it sound more Mexican. Working with a newspaper magnate, William Randolph Hearst, he created hysteria around the impact of cannabis on American youth and proclaimed an invasion of marijuana-smoking Mexican men assaulting white women. The ensuing public anxiety led to the drug being banned. The US then imposed its anti-cannabis stance on other western countries and this was finally imposed on the rest of the world through the first UN convention on narcotic drugs in 1961.

Mexican soldiers burning marijuana, cocaine, heroin and other drugs in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua. Photograph: AFP/Getty

This process of vilifying drugs by engendering a fear of the “other people” who use them became a recurring theme in drug policy. Black Americans were stigmatised on account of heroin use in the 1950s. In the 1960s hippies and psychedelics were targeted because they opposed the Vietnam war. In the 1970s it was again inner-city black Americans who used crack cocaine who received the brunt of opprobrium, so much so that the penalties for crack possession were 100 times higher than those for powder cocaine, despite almost equivalent pharmacology. Then came “crystal” (methamphetamine) and the targeting of “poor whites”.

The UK has followed US trends over cannabis, heroin and psychedelics, and led the world in the vilification of MDMA (ecstasy). In the UK a hate campaign against young people behaving differently was instigated by the rightwing press. As with past campaigns, they hid their prejudice under the smokescreen of false health concerns. It was very effective and resulted in both MDMA and raves being banned. This occurred despite the police being largely comfortable with MDMA users since they were friendly – a stark contrast to those at alcohol-fuelled events.

Since the demise of ecstasy we have seen the rise and fall of several alternative legal highs, most notably mephedrone. This was banned following a relentless media campaign, despite no evidence of deaths and with little attempt to properly estimate its harm. Subsequently we have discovered that it saved more lives than it took because so many people switched from cocaine and amphetamine to mephedrone that deaths from these more toxic stimulants decreased by up to 40%. Since mephedrone was banned in 2010, cocaine deaths have risen again and are now above their pre-mephedrone levels.

As young people seek to find legal ways to enjoy altered consciousness without exposing themselves to the addictiveness and toxicity of alcohol or the danger of getting a criminal record, so the newspapers seek to get these ways banned too. Politicians collude as they are subservient to those newspapers that hate youth and they know that the drug-using population is much less likely to vote than the drug-fearing elderly. We have moved to a surreal new world in which the government, through the new psychoactive substances bill, has decided to put an end to the sale of any drug with psychoactive properties, known or yet to be discovered.

This ban is predicated on more media hysteria about legal highs such as nitrous oxide and the “head shops” that sell them. Lies about the number of legal high deaths abound, with Mike Penning, minister for policing and justice, quoting 129 last year in the bill’s second reading. The true figure is about five, as the “head shops” generally now sell safe mild stimulants because they don’t want their regular customers to die.

The UK has followed US trends over cannabis, heroin and psychedelics, and led the world in the vilification of MDMA (ecstasy). In the UK a hate campaign against young people behaving differently was instigated by the rightwing press. As with past campaigns, they hid their prejudice under the smokescreen of false health concerns. It was very effective and resulted in both MDMA and raves being banned. This occurred despite the police being largely comfortable with MDMA users since they were friendly – a stark contrast to those at alcohol-fuelled events.

Since the demise of ecstasy we have seen the rise and fall of several alternative legal highs, most notably mephedrone. This was banned following a relentless media campaign, despite no evidence of deaths and with little attempt to properly estimate its harm. Subsequently we have discovered that it saved more lives than it took because so many people switched from cocaine and amphetamine to mephedrone that deaths from these more toxic stimulants decreased by up to 40%. Since mephedrone was banned in 2010, cocaine deaths have risen again and are now above their pre-mephedrone levels.

As young people seek to find legal ways to enjoy altered consciousness without exposing themselves to the addictiveness and toxicity of alcohol or the danger of getting a criminal record, so the newspapers seek to get these ways banned too. Politicians collude as they are subservient to those newspapers that hate youth and they know that the drug-using population is much less likely to vote than the drug-fearing elderly. We have moved to a surreal new world in which the government, through the new psychoactive substances bill, has decided to put an end to the sale of any drug with psychoactive properties, known or yet to be discovered.

This ban is predicated on more media hysteria about legal highs such as nitrous oxide and the “head shops” that sell them. Lies about the number of legal high deaths abound, with Mike Penning, minister for policing and justice, quoting 129 last year in the bill’s second reading. The true figure is about five, as the “head shops” generally now sell safe mild stimulants because they don’t want their regular customers to die.

‘Queen Victoria’s physician was a great proponent of the value of tincture of cannabis, and she is reputed to have used it to counteract the pain of menstrual periods and childbirth.’ Photograph: Alamy

The attack on nitrous oxide is even more peculiar as this gas has been used for pain control for women in childbirth and surgical pain treatments for more than 100 years with minimal evidence of harm. But when a couple of premiership footballers are filmed inhaling a nitrous oxide balloon, then it becomes a public health hazard. In typical fashion the press renamed it “hippy crack” to scare people – what could me more frightening to elderly readers than an invasion of hippies on crack? In truth, the effect of nitrous oxide is nothing like crack and no self-respecting hippy would ever use it. Still, it seems likely it will be banned along with every other mind-altering substance that is not exempted.

The psychoactive substances bill is the most oppressive law in terms of controlling moral behaviour since the Act of Supremacy in 1558 that banned the practice of the Catholic faith. Both are based on a moral superiority that specifies the state will decide on acceptable actions and beliefs even if they don’t affect other people. Worse, it won’t work – evidence from other countries such as Poland and Ireland that have tried such blanket bans shows an increase in deaths as people go back to older illegal drugs such as cocaine and heroin.

Moreover, it may seriously impede research in brain disorders, one of the few scientific areas in which the UK is still world-leading. But hey, who cares about the consequences of laws, so long as the police and the press are appeased?

So the short answer to the question “why are (some) drugs illegal?” is simple. It’s because the editors of powerful newspapers want it that way. They see getting drugs banned as a tangible measure of success, a badge of honour. And behind them the alcohol industry continues secretly to express its opposition to anything that might challenge its monopoly of recreational drug sales. But that’s another story.

Tuesday, 23 December 2014

Why the bouncer is not essential to cricket

Pranay Sanklecha in Cricinfo

The bouncer: not worth the risk © Getty Images

Enlarge

The death of Phillip Hughes was also the death of a certain kind of false, if sincere, innocence about the game. We are reminded that cricket balls can kill. So what should we do about bouncers?

The standard answer - unanimous, even, when it comes to the old pros who constitute the majority of those who write and talk about cricket, is: nothing. There is nothing to do. Keep calm and carry on. We must understand that what happened to Hughes was a tragic but freak accident (by the way, as Andy Bull wrote in the Guardian, such tragedies happen more often than we might unthinkingly assume). Be sad because it's a tragedy, but don't let it change anything because it was a freakish one.

Let one view stand for the rest. This is what Mark Richardson had to say:

Don't get me wrong. I don't want to see people getting seriously hurt and what happened to Phillip Hughes is just awful but what people have to accept is that this was such a freak occurrence and serious injury is still so rare that it does not in any way suggest cricket has a problem with the short ball at all. In fact, if cricket took away the bouncer, then we would have a problem. So let's mourn the loss of Phillip Hughes but not use it to grandstand unnecessarily.

I agree. Let's not grandstand unnecessarily. But let's also realise that this is a difficult question, and to dismiss the view that bouncers ought to be banned is itself unnecessary grandstanding, just from the opposite direction.

Let's first realise that there is a moral question here. When you run in and bowl a bouncer, you are (often, not always) aiming it at the batsman. If you're even halfway quick, you know - or after the death of Hughes you ought to, anyway - that you're doing something that carries a risk of causing death, a much greater risk than most other actions carried out while playing cricket.

It doesn't follow that you ought not to do it, or that you are to blame for doing it. What does follow is that you need a valid justification for doing it, and this is not provided by the trope that the bowler doesn't intend to hurt the batsman. Good for the bowler, but it still doesn't address the question of whether he's morally justified in imposing the risk of a very great harm on the batsman.

Now imposing a risk of a very great harm is not the same as imposing a great risk of harm. For instance, each time you fly, you run a tiny risk of a very great harm, while if you gently lob a pebble at someone from a few metres away, you impose a very big risk of a very small harm.

We seem comfortable with the former. Driving, for example, kills hundreds of thousands of people every year, but we do not believe that it should be banned. Why not? Because of roughly these two reasons: first, we believe that the benefits of the practice of driving outweigh the harm of the tragedies it causes; second, we believe that the risk of causing those harms is to some extent unavoidable. We try to minimise those risks, but we accept that given current technology we cannot eliminate them, and we accept them because of the value to us of being able to drive.

And this has been roughly the argument when it comes to bouncers. People outline its benefits: it's thrilling (which Test cricket needs to stay alive), it maintains the balance between bat and ball, it's a test of courage and thereby reveals character (men from boys and all that), it is part of the tradition of the game.

We can accept all of that, for the sake of the argument. But even after we do, we haven't justified the use of bouncers because there is one crucial difference between the practices of driving and of bowling bouncers.

For the justification of driving, it's crucial that its benefits can't be realised without running the accompanying risks. If they could, there would be absolutely no justification left for running those risks.

The bouncer does indeed create benefits. But it does not seem indispensable to creating them. Tradition is not justification, and even if it were, our traditions are mostly the innovations of an earlier time. Eliminating the bouncer would end a tradition, but it would simply be part of the story of the evolution of cricket, and many other traditions would remain. And if you want thrilling Test cricket and a competitive balance between bat and ball, you can achieve both by the simple expedient of making pitches better.

Eliminating the bouncer would end a tradition, but it would simply be part of the story of the evolution of cricket, and many other traditions would remain

One way of doing this would be, of course, to make pitches bouncier, which would increase the risk of inflicting harm, and this might seem to contradict my argument. To quote Mill, via Kipling, "nay, nay, not so, but far otherwise". First, leaving grass on, and allowing pitches to take spin, both make pitches more competitive without necessarily imparting greater bounce. Second, a bouncy pitch would certainly make it more likely that harm will be inflicted, but it's short-pitched bowling that would make it more likely to inflict great harm. And my argument is in part to do with proportionality. I'm not saying take the risk of harm out of the game, I'm saying (well, I will be shortly) that I can't see a good argument from risk vs benefit for imposing the great risks of bowling bouncers.

Make boundaries bigger while you're at it. As for courage and revealing character, well, there are any number of ways cricket does that without the bouncer. Sacrificing your wicket, playing in an unnatural style, bowling into the wind, your response to defeat and victory and misfortune - all these things reveal character. Facing spin on turning pitches is a test of courage, of confronting the fear of looking stupid. Calling for a crucial catch, standing under a ball that steeples high into the air and on which the fate of the game depends - this requires courage.

Ah, but the bouncer is special, people will say, because it's about physical courage. I agree with the latter but disagree with the former. A game with a hard ball travelling at speed will necessarily test physical courage. A game that requires the kind of unnatural exertion demanded of fast bowlers will necessarily test physical courage. A game that people play with niggling injuries, with broken fingers and torn hamstrings, as with in Michael Clarke's case basically no back - this game will test physical courage.

Some may have the intellectual honesty here to go the extreme position. The bouncer is special, they will say, because it tests - especially now, after the death of Hughes - the fear of death. And this testing creates benefits that nothing else can.

But even this, sadly, isn't true. It is not special in carrying the risk of death. To take the most recent example, think of the Israeli umpire who died because of a shot that ricocheted off the stumps. Simply by virtue of the hard ball, and the speeds at which it can be thrown and struck, cricket will always intrinsically carry the risk of causing death. People can die without bouncers being bowled. So even if you maintain that the fear of death is an essential part of cricket, you don't need bouncers to do it.

The point is not that we must make the game riskless. The only way this could even be attempted to be done is to make the ball soft. This would indeed destroy cricket. The point is that we must aim to reduce unnecessary risks. What are unnecessary risks? Well, a pretty good example is something which is not essential to creating the benefits associated with it, and something which directly increases the risk of deaths on the cricket field.

The bouncer.

I love the bouncer. It's electrifying, both to play and to watch. Atherton v Donald, Morkel v Clarke, Johnson 2.0 (or 3 or 4 or 7.7, new Mitch, moustachioed Mitch) v everyone. Who doesn't want to see that?

But I can't see an argument from the morality of risk that justifies it. I can see one other possibility, an argument from, roughly, the value of self-realisation. But reasons of space mean that will have to be the topic of a separate piece.

Wednesday, 19 February 2014

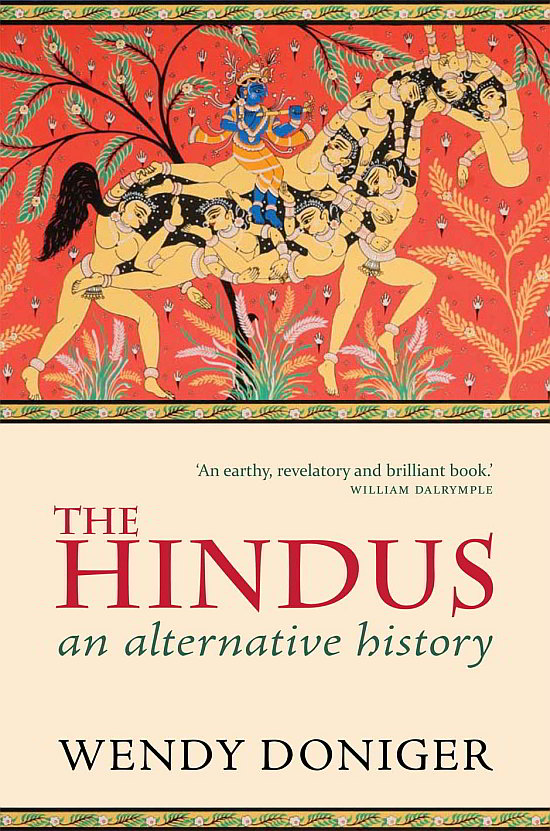

A great defence of the decision to stop publication of 'The Hindus by Wendy Doniger'

CONTROVERSY

Untangling The Knot

The many strands entangled in l' affaire Doniger involve issues that are too important to be left to the predictable and somewhat stale rhetoric about Hindutva fanatics or lamenting the role of the Indian government and judiciary

The controversy about Penguin India’s decision to withdraw and pulp Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternative History brings to the surface issues likely to trouble scholars of India for years to come. First, the obvious: the banning of any book violates academic or intellectual freedom. Rightly so, this leads to moral indignation among the intelligentsia of India and the West. Our ancestors fought for this freedom, sometimes sacrificing their lives. Not to protect it amounts to betraying their legacy.

Yet, in this case, the rhetoric is predictable and somewhat stale:

So many strands are entangled in this knotty affair that it is no longer clear what is at stake. To move ahead we first need to untangle the knot, but this requires that we take unexpected perspectives and question entrenched convictions. Drawing on the work of S.N. Balagangadhara, this piece hopes to give one such perspective.

I

Imagine you are born in the 1950s as a Hindu boy with intellectual inclinations. As you grow up, your mother takes you to the temple and shows you how to do puja. Your grandparents tell you stories about Bhima’s strength, Krishna’s appetite, Durvasa’s temper… Perhaps you rejoice when Rama rescues Sita, feel afraid when Kali fights demons, or cry when Drona demands Ekalavya’s thumb as gurudakshina. Your father is indifferent to most of this stuff, but then he is very moody so you prefer to stay away from him in any case.

In school, you are taught about the history of India. You learn that Hinduism grew out of the Brahmanism imported during the Aryan invasion. The caste system is a fourfold hierarchy imposed by the Brahmin priesthood, so you are told, and untouchability is the bane of Hindu society. Caste discrimination needs to be eradicated, as Gandhi said, while the scientific temper should displace superstitious tradition, as Nehru taught.

Your teachers present this account as the truth, along with Newton’s physics and Darwin’s evolutionary theory. You feel bad about your “backward religion” and ashamed about “the massive injustice of caste.” For some time, as a student, you also mouth this story in the name of progress and social justice. Yet you feel that there is something fundamentally wrong with it. You sense that it misrepresents you and your traditions—it distorts your practices, your people, and your experience, but you don’t know what to do about it.

What is the problem? Well, the current discourse on Indian culture and society is deeply flawed, even though it dominates the educational system and the media. This story about “Hindu religion” and “the caste system” started out as an attempt by European minds to make sense of their experience of India. Missionaries, travellers, and colonial officials collected their observations; Orientalists and other scholars ordered these into a coherent image of India. In the process, they drew on a set of commonplaces widespread in European societies, which all too often reflected a Christian critique of false religion.

The resulting story transforms India into a deficient culture:

II

Back to the 1970s now: you are studying hard, for your parents want you to become an engineer. Yet you are more interested in history and the social sciences. You want to make sense of your unease with the dominant story about Indian culture. So you turn to the works of eminent professors at elite universities from the Ivy League to JNU. What do you find? They repeat the same story, in a jargon that makes it even more opaque. You become more frustrated. Everywhere you turn, people just reproduce the same story about Hinduism and caste as the worst thing that ever happened to humanity: politicians, activists, teachers, professors, newspapers, television shows… They may add some qualifications but to no avail. After spending a few years in America, you return to India, get married, and have two kids. They come home from school with questions about “the wrongs of Hinduism and the caste system.” You don’t know what to tell them. Your frustration and anger rise to boiling point. You feel betrayed by the intellectual classes.

What are the options of Indians going through similar experiences? They cannot challenge the story about Hinduism and caste intellectually for they do not possess the tools to do so. They are neither scholars nor social scientists so they cannot be expected to grasp the conceptual foundations of the dominant story, let alone develop an alternative. Maximally, they can condemn it as “racist” or “imperialist.” Even there, they are ambiguous. They feel that the West is ahead of India in so many ways. In their society, corruption is the rule and the caste system refuses to go away, but then most people around them nevertheless appear to be good men and women. How to make sense of this? There are no thinkers able to help them solve these problems.

III

When you turn 45, your children leave home. One fine day a colleague tells you he is with the RSS and hands you some literature. Here is an outlet for venting your anger and frustration, the rhetoric of Hindu nationalism:

“Be a patriotic Indian; the Hindu nation is great; caste is only a blot on its glory; Indian intellectuals are communists engaged in an anti-Indian conspiracy; and foreign scholars must be out to divide the country.”

This rhetoric does not give you any enlightenment or insights into your traditions; actually, it feels quite shallow. But it at least gives some relief and puts an end to the blame and insult heaped onto your traditions. With some fellow warriors you decide that the miseducation of India should stop. What is the next step?

At this point, there are ready made traps. First, it is difficult not to notice how those in power in India decide what gets written in the textbooks. Under British rule, it was the classical Orientalist account. Mrs Gandhi allowed the Marxists to take control of the relevant government bodies (they could acquire only “soft power” there, after all) and reject Indian culture as a particularly backward instance of false consciousness. For decades now, secularists have set the agenda and funded research projects and centres for “humiliation and exclusion studies.” Once the BJP comes to power, why not rewrite the textbooks and run educational bodies according to Hindutva tastes?

Second, there are examples of successful attempts at having books banned in the name of religion. Rushdie’s Satanic Verses is the cause célèbre. The relevant section of the Indian Penal Code crystallized in the context of early 20th-century controversies about texts that ridiculed the Prophet Muhammad. At the time, some jurists argued that non-Muslims could not be expected to endorse the special status given by Muslims to Muhammad as the messenger of God. That would indirectly force all citizens to accept Islam as true religion. Yet it was precisely there that Muslim litigants succeeded. If one group could use the law to indirectly compel all citizens to accept its claims concerning its holy book, religious doctrines and divine prophet, why not follow the same route?

Third, American scholars of religion came in handy for once. They had identified some questions they considered central to religious studies: What is the relation between insider and outsider perspectives? Who has the right to speak for a religion, the believer or the scholar? Originally, these were questions essential to a religion like Christianity, where accepting God’s revelation is the precondition of grasping its message. Yet the potential answers turned out to be useful to others: “Only Hindus should speak for Hinduism and scholarship can be allowed only in so far as it respects the believer’s perspective.”

What gives Hindu nationalists the capacity to conform so easily to these models? This is because they generally reproduce the Orientalist story about Hinduism, just adding another value judgement. They may believe they are fighting the secularists; in fact, they are also prisoners of what Balagangadhara has called “colonial consciousness.” That is, the Western discourse about India functions as the descriptive framework through which Hindu nationalists understand themselves and their culture. They also accept that this culture is constituted by a religion with its own sacred scriptures, gods, revelations, and doctrines. Within this framework, they can then easily mimic Islamic and Christian concerns about blasphemy and offence. Add the 19th-century Victorian prudishness adopted by the Indian middle class and you get prominent strands of the Doniger affair.

Consider the petition by Dinanath Batra and the Shiksha Bachao Andolan Samiti. Doniger’s suggestion that the Ramayana is a work of fiction written by human authors—a claim that would hardly create a stir in most Indians—is now transformed into a violation of the sacred scriptures of Hinduism. The petition claims that the cover of the book is offensive because “Lord Krishna is shown sitting on buttocks of a naked woman surrounded by other naked women” and that Doniger’s approach is that “of a woman hungry of sex.” It expresses shock at her claim that some Sanskrit texts reflect the “glorious sexual openness and insight” of the era in which they were written. To anyone familiar with the harm caused by Christian attitudes towards sex-as-sin, this would count as a reason to be proud of Indian culture. Yet the grips of Victorian morality have made these Hindus ashamed of a beautiful dimension of their traditions.

IV

In the meantime, our middle-aged gentleman’s daughter has gone into the humanities and her excellent results give her entry to a PhD programme in religious studies at an Ivy League university. After some months, she begins to feel disappointed by the shallowness of the teaching and research. When compared to, say, the study of Buddhism, where a variety of perspectives flourish, Hinduism studies appears to be in a state of theoretical poverty. Refusing to take on the role of the native informant, she begins to voice her disagreement with her teachers. This is not appreciated and she soon learns that she has been branded “Hindutva.”

Around the same time, she detects a series of factual howlers and flawed translations in the works of eminent American scholars of Hinduism. When she points these out, several of her professors turn cold towards her. She is no longer invited to reading groups and is avoided at the annual meetings of the American Academy of Religion. In response, this budding researcher begins to engage in self-censorship and looks for comfort among NRI families living nearby. Her dissertation, considered groundbreaking by some international colleagues, gets hardly any response from her supervisors. Looking for a job, the difficulties grow: she needs references from her professors but whom can she ask? She applies to some excellent universities but is never shortlisted. Confidentially, a senior colleague tells her that her reputation as a Hindutva sympathiser precedes her. Eventually, she gets a tenure-track position at some university in small-town Virginia, where she feels so isolated and miserable that she decides to return to India.

Intellectual freedom can be curbed in many ways. The current academic discourse on Indian culture is as dogmatic as its advocates are intolerant of alternative paradigms. They trivialize genuine critique by reducing this to some variety of “Hindu nationalism” or “romantic revivalism.” All too often ad hominem considerations (about the presumed ideological sympathies of an author) override cognitive assessment. Thus, alternative voices in the academic study of Indian culture are actively marginalized. This modus operandi constitutes one of the causes behind the growing hostility towards the doyens of Hinduism studies.

Again this strand surfaces in the Doniger affair. When critics pointed out factual blunders from the pages of The Hindus, this appears to have been happily ignored by Doniger and her publisher. She is known for her dismissal of all opposition to her work as tantrums of the Hindutva brigade. The debates on online forums like Kafila.org (a blog run by “progressive” South Asian intellectuals) smack of contempt for the “Hindu fanatics,” “fundamentalists” or “fascists” (read Arundathi Roy’s open letter to Penguin). More importantly, they show a refusal to examine the possibility that books by Doniger and other “eminent” scholars might be problematic because of purely cognitive reasons.

For instance, the petition charges Doniger with an agenda of Christian proselytizing hidden behind the “tales of sex and violence” she tells about Hinduism. This generates ridicule: Doniger is Jewish and she is a philologist not a missionary. Indeed, this point appears ludicrous and lacks credibility when put so crudely. As said, it also reflects the Victorian prudishness to which some social layers have succumbed. Yet, it pays off to try and understand this issue from a cognitive point of view.

A major problem of early Christianity in the Roman Empire was how to distinguish true Christians from pagan idolaters. Originally, martyrdom had been a helpful criterion but, once Christianity became dominant, the persecution ended and there were no more martyrs to be found. The distinction between true and false religion could not limit itself to specific religious acts. Those who followed the true God should also be demarcated from the followers of false gods by their everyday behaviour. Sex became a central criterion here. Christians were characterized in terms of chastity as opposed to pagan debauchery. (If you wish to see how this image of Greco-Roman paganism lives on in America, watch an episode of the television series Spartacus.)

From then on, Christians believed they could recognize false religion and its followers in terms of lewd sexual practices. Early travel reports sent from India to Europe, like those of the Italian traveller Ludovico di Varthema, confirmed this image of pagan idolatry: “Brahmin priests” and “superstitious believers” engaged in a variety of “obscene” practices from deflowering virgins in various ways to swapping wives for a night or two. Conversion to Christianity would entail conversion to chastity.

Reinforced by Victorian obsessions, this style of representing Indian religion reached its climax in the late 19th century. Hinduism was said to be the prime instance of “sex worship” and “phallicism,” notions popular at the time for explaining the origin of religion. Take a work by Hargrave Jennings—cleric, freemason, amateur of comparative religion—imaginatively titledPhallic Miscellanies; Facts and Phases of Ancient and Modern Sex Worship, As Illustrated Chiefly in the Religions of India (1891). The opening sentence goes thus: “India, beyond all countries on the face of the earth, is pre-eminently the home of the worship of the Phallus—the Linga puja; it has been so for ages and remains so still. This adoration is said to be one of the chief, if not the leading dogma of the Hindu religion…”It goes on to explain that “according to the Hindus, the Linga is God and God is the Linga; the fecundator, the generator, the creator in fact.” In other words, the Hindus view the phallus as their divine Creator and its worship is their dogma. This is one of a series of works from this period, expressing both fascination and disgust.

This focus on sex remained central to the popular image of Indian religion in the Western world. In her infamous Mother India (1927), the American Katherine Mayo writes that the Hindu infant that survives the birth-strain, “a feeble creature at best, bankrupt in bone-stuff and vitality, often venereally poisoned, always predisposed to any malady that may be afloat,” is raised by a mother guided by primitive superstitions. “Because of her place in the social system, child-bearing and matters of procreation are the woman’s one interest in life, her one subject of conversation, be her caste high or low. Therefore, the child growing up in the home learns, from earliest grasp of word and act, to dwell upon sex relations” . From there, Mayo turns to a reflection on the obsession for “the male generative organ” in Hindu religion. Among the consequences are child marriage and other immoral practices: “Little in the popular Hindu code suggests self-restraint in any direction, least of all in sex relations” .

In short, the connection established between Hinduism and sexuality was based in a Christian frame that served to distinguish pagan idolaters from true believers. Wendy Doniger’s work builds on this tradition. Like some of her predecessors, she appreciates the sexual freedom involved, but then she also tends to stress two aspects: sex and caste. This is not a coincidence, for these always counted as two major properties allowing Western audiences to appreciate the supposed inferiority of Hinduism. In other words, the sense that the current depiction of Indian traditions in terms of caste and sex is connected to earlier Christian critiques of false religion cannot be dismissed so easily.

Does this mean that researchers should give in to the campaigns of holier-than-thou bigots? Does it justify the banning or withdrawal of books? Not at all! First, who will decide what counts as true knowledge and what as salacious or gratuitous insult? In the US, evangelicals would like to remove Darwin’s Origin of Species from schools because they consider it unscientific and offensive. If it continues to follow its current route, the Indian judiciary may well end up banning a variety of such books. Second, book bans fail to have any fundamental effect on the kind of work produced about India. The epitome of the “sex and caste” genre, Arthur Miles’ The Land of the Lingam(1937), was banned many decades ago. Even though political correctness altered the language use and removed explicit mockery, many works continue to represent Hinduism along similar lines. Third, the Kama Sutra and the Koka Shastra, the temples of Khajuraho and Konarak, Tantric traditions and the Indian science of erotics are all fascinating phenomena, which need to be studied and understood. But we have an equal responsibility to make sense of the concerns of Indians horrified by the currently dominant depiction of their traditions. All this research should happen in complete freedom or it shall not happen at all.

V

The dispute about Doniger’s book is a product of all these forces, including the peculiarities of the Indian Penal Code (better left to legal experts). What is the way out? How can we untangle the knot?

To cope with complex cases like these, the first step should take the form of scientific research. The disagreement with the work of Doniger and other scholars can be expressed in a reasonable manner. The theoretical poverty and shoddy way of dealing with facts and translations exhibited by such works can be challenged on cognitive grounds. This is the only way to alleviate the frustration of our Hindu gentleman (a grandfather by now) and to illuminate the intellectual concerns of his daughter. In any case, we need to appreciate how the current story about Hinduism and caste continues to reproduce ideas derived from Christianity and its conceptual frameworks. As long as we keep selling the experience that one form of life (Western culture) has had of another (Indian culture) as God-given truth, the current conflict will not abate and our understanding of India will not progress.

But the same goes for using the Indian Penal Code to have books banned. Inevitably, this has chilling effects on the search for knowledge, at a time when India needs free research more than ever to save it from catastrophe. As is always the case, scientific research will bring about unexpected and unorthodox results. At any point, some or another group may feel offended by these, but this should never prevent us from continuing to pursue truth.

Unfortunately, the Indian government and judiciary have taken the route of succumbing to “offence” and “atrocity” claims by all kinds of communities. Given the political situation, this is unlikely to change any time soon. We can express moral outrage today. But tomorrow the challenge is to develop hypotheses that make sense of the current developments in India, including the violent rejection of the dominant representations of Indian culture. These need to show the way to new solutions so that an end may be brought to the banning and destruction of books in a culture that was always known for its intellectual freedom.

Yet, in this case, the rhetoric is predictable and somewhat stale:

“Another bunch of Hindutva fanatics have succeeded in having a book by a respected academic banned because they feel offended by its contents. They have not understood the book, give ridiculous reasons, and threaten publisher and author with dire consequences if the book is not withdrawn. The Indian judiciary is caving in to religious fanaticism and practically abolishing freedom of speech in India.”This readymade reaction may sound cogent but it covers up major questions: What brings Hindu organizations to filing petitions that make them the butt of ridicule and contempt? Whence the frustration among so many Indians about the way their culture is depicted? Why is this battle not fought out in the free intellectual debate so typical of India in the past?

So many strands are entangled in this knotty affair that it is no longer clear what is at stake. To move ahead we first need to untangle the knot, but this requires that we take unexpected perspectives and question entrenched convictions. Drawing on the work of S.N. Balagangadhara, this piece hopes to give one such perspective.

I

Imagine you are born in the 1950s as a Hindu boy with intellectual inclinations. As you grow up, your mother takes you to the temple and shows you how to do puja. Your grandparents tell you stories about Bhima’s strength, Krishna’s appetite, Durvasa’s temper… Perhaps you rejoice when Rama rescues Sita, feel afraid when Kali fights demons, or cry when Drona demands Ekalavya’s thumb as gurudakshina. Your father is indifferent to most of this stuff, but then he is very moody so you prefer to stay away from him in any case.

In school, you are taught about the history of India. You learn that Hinduism grew out of the Brahmanism imported during the Aryan invasion. The caste system is a fourfold hierarchy imposed by the Brahmin priesthood, so you are told, and untouchability is the bane of Hindu society. Caste discrimination needs to be eradicated, as Gandhi said, while the scientific temper should displace superstitious tradition, as Nehru taught.

Your teachers present this account as the truth, along with Newton’s physics and Darwin’s evolutionary theory. You feel bad about your “backward religion” and ashamed about “the massive injustice of caste.” For some time, as a student, you also mouth this story in the name of progress and social justice. Yet you feel that there is something fundamentally wrong with it. You sense that it misrepresents you and your traditions—it distorts your practices, your people, and your experience, but you don’t know what to do about it.

What is the problem? Well, the current discourse on Indian culture and society is deeply flawed, even though it dominates the educational system and the media. This story about “Hindu religion” and “the caste system” started out as an attempt by European minds to make sense of their experience of India. Missionaries, travellers, and colonial officials collected their observations; Orientalists and other scholars ordered these into a coherent image of India. In the process, they drew on a set of commonplaces widespread in European societies, which all too often reflected a Christian critique of false religion.

The resulting story transforms India into a deficient culture:

“India has its dominant religion, Hinduism, created by cunning Brahmin priests; this religion sanctions social injustice in the form of a fixed caste hierarchy; instead of freedom and equality, it represents inequality and social constraint; it is basically immoral.”With some internal variation, this story is presented as a truthful description of Indian culture. Contemporary authors use different conceptual vocabularies to explain or interpret “Hinduism” and “caste,” from Marx and Freud to Foucault and Žižek. But the so-called “facts” they seek to explain are already claims of the Orientalist discourse, structured around theological ideas in secular guise. In fact, they are nothing more than reflections of how Europeans experienced India. No wonder then that the story does not make sense to those who do not share this experience.

II

Back to the 1970s now: you are studying hard, for your parents want you to become an engineer. Yet you are more interested in history and the social sciences. You want to make sense of your unease with the dominant story about Indian culture. So you turn to the works of eminent professors at elite universities from the Ivy League to JNU. What do you find? They repeat the same story, in a jargon that makes it even more opaque. You become more frustrated. Everywhere you turn, people just reproduce the same story about Hinduism and caste as the worst thing that ever happened to humanity: politicians, activists, teachers, professors, newspapers, television shows… They may add some qualifications but to no avail. After spending a few years in America, you return to India, get married, and have two kids. They come home from school with questions about “the wrongs of Hinduism and the caste system.” You don’t know what to tell them. Your frustration and anger rise to boiling point. You feel betrayed by the intellectual classes.

What are the options of Indians going through similar experiences? They cannot challenge the story about Hinduism and caste intellectually for they do not possess the tools to do so. They are neither scholars nor social scientists so they cannot be expected to grasp the conceptual foundations of the dominant story, let alone develop an alternative. Maximally, they can condemn it as “racist” or “imperialist.” Even there, they are ambiguous. They feel that the West is ahead of India in so many ways. In their society, corruption is the rule and the caste system refuses to go away, but then most people around them nevertheless appear to be good men and women. How to make sense of this? There are no thinkers able to help them solve these problems.

III

When you turn 45, your children leave home. One fine day a colleague tells you he is with the RSS and hands you some literature. Here is an outlet for venting your anger and frustration, the rhetoric of Hindu nationalism:

“Be a patriotic Indian; the Hindu nation is great; caste is only a blot on its glory; Indian intellectuals are communists engaged in an anti-Indian conspiracy; and foreign scholars must be out to divide the country.”

This rhetoric does not give you any enlightenment or insights into your traditions; actually, it feels quite shallow. But it at least gives some relief and puts an end to the blame and insult heaped onto your traditions. With some fellow warriors you decide that the miseducation of India should stop. What is the next step?

At this point, there are ready made traps. First, it is difficult not to notice how those in power in India decide what gets written in the textbooks. Under British rule, it was the classical Orientalist account. Mrs Gandhi allowed the Marxists to take control of the relevant government bodies (they could acquire only “soft power” there, after all) and reject Indian culture as a particularly backward instance of false consciousness. For decades now, secularists have set the agenda and funded research projects and centres for “humiliation and exclusion studies.” Once the BJP comes to power, why not rewrite the textbooks and run educational bodies according to Hindutva tastes?

Second, there are examples of successful attempts at having books banned in the name of religion. Rushdie’s Satanic Verses is the cause célèbre. The relevant section of the Indian Penal Code crystallized in the context of early 20th-century controversies about texts that ridiculed the Prophet Muhammad. At the time, some jurists argued that non-Muslims could not be expected to endorse the special status given by Muslims to Muhammad as the messenger of God. That would indirectly force all citizens to accept Islam as true religion. Yet it was precisely there that Muslim litigants succeeded. If one group could use the law to indirectly compel all citizens to accept its claims concerning its holy book, religious doctrines and divine prophet, why not follow the same route?

Third, American scholars of religion came in handy for once. They had identified some questions they considered central to religious studies: What is the relation between insider and outsider perspectives? Who has the right to speak for a religion, the believer or the scholar? Originally, these were questions essential to a religion like Christianity, where accepting God’s revelation is the precondition of grasping its message. Yet the potential answers turned out to be useful to others: “Only Hindus should speak for Hinduism and scholarship can be allowed only in so far as it respects the believer’s perspective.”

What gives Hindu nationalists the capacity to conform so easily to these models? This is because they generally reproduce the Orientalist story about Hinduism, just adding another value judgement. They may believe they are fighting the secularists; in fact, they are also prisoners of what Balagangadhara has called “colonial consciousness.” That is, the Western discourse about India functions as the descriptive framework through which Hindu nationalists understand themselves and their culture. They also accept that this culture is constituted by a religion with its own sacred scriptures, gods, revelations, and doctrines. Within this framework, they can then easily mimic Islamic and Christian concerns about blasphemy and offence. Add the 19th-century Victorian prudishness adopted by the Indian middle class and you get prominent strands of the Doniger affair.

Consider the petition by Dinanath Batra and the Shiksha Bachao Andolan Samiti. Doniger’s suggestion that the Ramayana is a work of fiction written by human authors—a claim that would hardly create a stir in most Indians—is now transformed into a violation of the sacred scriptures of Hinduism. The petition claims that the cover of the book is offensive because “Lord Krishna is shown sitting on buttocks of a naked woman surrounded by other naked women” and that Doniger’s approach is that “of a woman hungry of sex.” It expresses shock at her claim that some Sanskrit texts reflect the “glorious sexual openness and insight” of the era in which they were written. To anyone familiar with the harm caused by Christian attitudes towards sex-as-sin, this would count as a reason to be proud of Indian culture. Yet the grips of Victorian morality have made these Hindus ashamed of a beautiful dimension of their traditions.

IV

In the meantime, our middle-aged gentleman’s daughter has gone into the humanities and her excellent results give her entry to a PhD programme in religious studies at an Ivy League university. After some months, she begins to feel disappointed by the shallowness of the teaching and research. When compared to, say, the study of Buddhism, where a variety of perspectives flourish, Hinduism studies appears to be in a state of theoretical poverty. Refusing to take on the role of the native informant, she begins to voice her disagreement with her teachers. This is not appreciated and she soon learns that she has been branded “Hindutva.”

Around the same time, she detects a series of factual howlers and flawed translations in the works of eminent American scholars of Hinduism. When she points these out, several of her professors turn cold towards her. She is no longer invited to reading groups and is avoided at the annual meetings of the American Academy of Religion. In response, this budding researcher begins to engage in self-censorship and looks for comfort among NRI families living nearby. Her dissertation, considered groundbreaking by some international colleagues, gets hardly any response from her supervisors. Looking for a job, the difficulties grow: she needs references from her professors but whom can she ask? She applies to some excellent universities but is never shortlisted. Confidentially, a senior colleague tells her that her reputation as a Hindutva sympathiser precedes her. Eventually, she gets a tenure-track position at some university in small-town Virginia, where she feels so isolated and miserable that she decides to return to India.

Intellectual freedom can be curbed in many ways. The current academic discourse on Indian culture is as dogmatic as its advocates are intolerant of alternative paradigms. They trivialize genuine critique by reducing this to some variety of “Hindu nationalism” or “romantic revivalism.” All too often ad hominem considerations (about the presumed ideological sympathies of an author) override cognitive assessment. Thus, alternative voices in the academic study of Indian culture are actively marginalized. This modus operandi constitutes one of the causes behind the growing hostility towards the doyens of Hinduism studies.

Again this strand surfaces in the Doniger affair. When critics pointed out factual blunders from the pages of The Hindus, this appears to have been happily ignored by Doniger and her publisher. She is known for her dismissal of all opposition to her work as tantrums of the Hindutva brigade. The debates on online forums like Kafila.org (a blog run by “progressive” South Asian intellectuals) smack of contempt for the “Hindu fanatics,” “fundamentalists” or “fascists” (read Arundathi Roy’s open letter to Penguin). More importantly, they show a refusal to examine the possibility that books by Doniger and other “eminent” scholars might be problematic because of purely cognitive reasons.

For instance, the petition charges Doniger with an agenda of Christian proselytizing hidden behind the “tales of sex and violence” she tells about Hinduism. This generates ridicule: Doniger is Jewish and she is a philologist not a missionary. Indeed, this point appears ludicrous and lacks credibility when put so crudely. As said, it also reflects the Victorian prudishness to which some social layers have succumbed. Yet, it pays off to try and understand this issue from a cognitive point of view.

A major problem of early Christianity in the Roman Empire was how to distinguish true Christians from pagan idolaters. Originally, martyrdom had been a helpful criterion but, once Christianity became dominant, the persecution ended and there were no more martyrs to be found. The distinction between true and false religion could not limit itself to specific religious acts. Those who followed the true God should also be demarcated from the followers of false gods by their everyday behaviour. Sex became a central criterion here. Christians were characterized in terms of chastity as opposed to pagan debauchery. (If you wish to see how this image of Greco-Roman paganism lives on in America, watch an episode of the television series Spartacus.)

From then on, Christians believed they could recognize false religion and its followers in terms of lewd sexual practices. Early travel reports sent from India to Europe, like those of the Italian traveller Ludovico di Varthema, confirmed this image of pagan idolatry: “Brahmin priests” and “superstitious believers” engaged in a variety of “obscene” practices from deflowering virgins in various ways to swapping wives for a night or two. Conversion to Christianity would entail conversion to chastity.

Reinforced by Victorian obsessions, this style of representing Indian religion reached its climax in the late 19th century. Hinduism was said to be the prime instance of “sex worship” and “phallicism,” notions popular at the time for explaining the origin of religion. Take a work by Hargrave Jennings—cleric, freemason, amateur of comparative religion—imaginatively titledPhallic Miscellanies; Facts and Phases of Ancient and Modern Sex Worship, As Illustrated Chiefly in the Religions of India (1891). The opening sentence goes thus: “India, beyond all countries on the face of the earth, is pre-eminently the home of the worship of the Phallus—the Linga puja; it has been so for ages and remains so still. This adoration is said to be one of the chief, if not the leading dogma of the Hindu religion…”It goes on to explain that “according to the Hindus, the Linga is God and God is the Linga; the fecundator, the generator, the creator in fact.” In other words, the Hindus view the phallus as their divine Creator and its worship is their dogma. This is one of a series of works from this period, expressing both fascination and disgust.

This focus on sex remained central to the popular image of Indian religion in the Western world. In her infamous Mother India (1927), the American Katherine Mayo writes that the Hindu infant that survives the birth-strain, “a feeble creature at best, bankrupt in bone-stuff and vitality, often venereally poisoned, always predisposed to any malady that may be afloat,” is raised by a mother guided by primitive superstitions. “Because of her place in the social system, child-bearing and matters of procreation are the woman’s one interest in life, her one subject of conversation, be her caste high or low. Therefore, the child growing up in the home learns, from earliest grasp of word and act, to dwell upon sex relations” . From there, Mayo turns to a reflection on the obsession for “the male generative organ” in Hindu religion. Among the consequences are child marriage and other immoral practices: “Little in the popular Hindu code suggests self-restraint in any direction, least of all in sex relations” .

In short, the connection established between Hinduism and sexuality was based in a Christian frame that served to distinguish pagan idolaters from true believers. Wendy Doniger’s work builds on this tradition. Like some of her predecessors, she appreciates the sexual freedom involved, but then she also tends to stress two aspects: sex and caste. This is not a coincidence, for these always counted as two major properties allowing Western audiences to appreciate the supposed inferiority of Hinduism. In other words, the sense that the current depiction of Indian traditions in terms of caste and sex is connected to earlier Christian critiques of false religion cannot be dismissed so easily.

Does this mean that researchers should give in to the campaigns of holier-than-thou bigots? Does it justify the banning or withdrawal of books? Not at all! First, who will decide what counts as true knowledge and what as salacious or gratuitous insult? In the US, evangelicals would like to remove Darwin’s Origin of Species from schools because they consider it unscientific and offensive. If it continues to follow its current route, the Indian judiciary may well end up banning a variety of such books. Second, book bans fail to have any fundamental effect on the kind of work produced about India. The epitome of the “sex and caste” genre, Arthur Miles’ The Land of the Lingam(1937), was banned many decades ago. Even though political correctness altered the language use and removed explicit mockery, many works continue to represent Hinduism along similar lines. Third, the Kama Sutra and the Koka Shastra, the temples of Khajuraho and Konarak, Tantric traditions and the Indian science of erotics are all fascinating phenomena, which need to be studied and understood. But we have an equal responsibility to make sense of the concerns of Indians horrified by the currently dominant depiction of their traditions. All this research should happen in complete freedom or it shall not happen at all.

V

The dispute about Doniger’s book is a product of all these forces, including the peculiarities of the Indian Penal Code (better left to legal experts). What is the way out? How can we untangle the knot?

To cope with complex cases like these, the first step should take the form of scientific research. The disagreement with the work of Doniger and other scholars can be expressed in a reasonable manner. The theoretical poverty and shoddy way of dealing with facts and translations exhibited by such works can be challenged on cognitive grounds. This is the only way to alleviate the frustration of our Hindu gentleman (a grandfather by now) and to illuminate the intellectual concerns of his daughter. In any case, we need to appreciate how the current story about Hinduism and caste continues to reproduce ideas derived from Christianity and its conceptual frameworks. As long as we keep selling the experience that one form of life (Western culture) has had of another (Indian culture) as God-given truth, the current conflict will not abate and our understanding of India will not progress.

But the same goes for using the Indian Penal Code to have books banned. Inevitably, this has chilling effects on the search for knowledge, at a time when India needs free research more than ever to save it from catastrophe. As is always the case, scientific research will bring about unexpected and unorthodox results. At any point, some or another group may feel offended by these, but this should never prevent us from continuing to pursue truth.

Unfortunately, the Indian government and judiciary have taken the route of succumbing to “offence” and “atrocity” claims by all kinds of communities. Given the political situation, this is unlikely to change any time soon. We can express moral outrage today. But tomorrow the challenge is to develop hypotheses that make sense of the current developments in India, including the violent rejection of the dominant representations of Indian culture. These need to show the way to new solutions so that an end may be brought to the banning and destruction of books in a culture that was always known for its intellectual freedom.

Thursday, 1 August 2013

Audi Drivers

Audi Drivers

Girish Menon

1/08/2013

Your speed limit is @ seventy

To protect each road user

But I'll drive my Audi @ one sixty

Coz I am not a loser

The judge banned me for three years

And fined me five one five

Fine, I said, will you take cash

It's time for my next drive

None of your laws will stop me

I've got more cash than you think

I can buy your cops and judges

With my tax haven market riches

Your income tax is @ 45 percent

To protect every lazy Briton

But I will pay @ zero percent

Coz I am not a cretin

The taxman may audit my books

To get cash for the treasury

His mates help me cook the books

And I won't share my luxury

None of your laws will stop me

I've got more cash than you think

I can buy your rulers and judges

With my tax haven market riches

Girish Menon

1/08/2013

Your speed limit is @ seventy

To protect each road user

But I'll drive my Audi @ one sixty

Coz I am not a loser

The judge banned me for three years

And fined me five one five

Fine, I said, will you take cash

It's time for my next drive

None of your laws will stop me

I've got more cash than you think

I can buy your cops and judges

With my tax haven market riches

Your income tax is @ 45 percent

To protect every lazy Briton

But I will pay @ zero percent

Coz I am not a cretin

The taxman may audit my books

To get cash for the treasury

His mates help me cook the books

And I won't share my luxury

None of your laws will stop me

I've got more cash than you think

I can buy your rulers and judges

With my tax haven market riches

Thursday, 4 July 2013

Ban qat? Theresa May might as well ban cats

A simple analogy shows how absurd the basis for the home secretary's drug prohibition plan really is

Qat and a cat – equally harmful to society? Photographs: Martin Godwin for the Guardian (left); Chip Mitchell/Getty Images (right)

Now this is embarrassing. I'm expected to have something to say about Theresa May's intention to ban the plant-drug qat, but due to a texting error by a new intern, I'd been preparing my thoughts on the Tory plan to ban cats, a plan which I now learn may not exist. Fortunately for her, I find that many of the same arguments apply, so I'm not quite back at square one.

The proponents of a ban on cats qat may be well intentioned, but rely on a mixture of exaggerated, selective, anecdotal, prejudiced and most frequently erroneous and illogical arguments. Cats are Qat is indeed associated with harm, which can be very serious at times, but it is unwise to generalise from the most extreme cases, or assume that cats areqat is solely to blame for complex problems of owners users.

Advocates for a ban are sometimes prone to demonise cats qat and, cynically or credulously, to fuel unfounded fears against owners users. Historically, cat owners were persecuted as witches. Qat users find themselves linked spuriously to terrorists, the ultimate folk-devils of our era.

Despite all the rhetoric, when detailed studies are made that explore the actual empirical evidence, suspicions about the dangers of cats qat are revealed time after time to have little basis in reality. A balanced assessment also exposes the prejudices of those campaigning for a ban on cats qat. Theresa May, who wants to disregard expert advisers and label as criminals any people who possess cats qat, has disregarded the evidence before, personally undermining her own government's promise to reduce the far greater harms caused by dogs alcohol.

By nearly every possible objective measure, dogs cause alcohol causes far greater danger to health, life and society at large than cats qat, or indeed any other pet drug. People rightly worry about the harm caused to society when people are irresponsible with dogsalcohol: the thousands of hospital admissions; the mess and intimidation we encounter on our city streets. However, insight and experience show that these harms to society can best be minimised through education, co-operation and maybe regulation, not by criminalisation and ostracism. Bans offer an opportunity for governments to posture and express their toughness to the electorate, but our legislative agenda should be driven not by the naive assumption that simple bans solve complex problems, but by evidence of what might actually best serve the interests of the public.

Those wanting a ban on cats qat might do well to consider the historical precedent. Driven by tabloid hysteria, the UK government introduced The Dangerous Dogs Act 1991, banning four breeds of dog. Since then, hospitalisations for dog bites have more thanquadrupled, with experts highlighting the absurdity of criminalising possession of particular types of dog instead of addressing issues of owner behaviour and responsibility. Driven by a moral agenda, alcohol was banned in the US in the 1920s, successfully handing the trade to organised crime networks. While prohibition probably reduced consumption, overall harm rose as the people most harmed by alcohol were denied the help they needed and were instead branded criminals. Now in the UK, the freedom of individuals to lawfully own a dog drink is respected, and we recognise even that petsalcohol might have some social value too.

Those who don't like going near dogs alcohol, who think that dog owners drinkers are wasting good money on dog food alcohol and valuable family time going on walkies to the pub have a valid opinion, but we don't think their values should be imposed on others through the criminal justice system. The same is true of cats qat: no one should mistake their inalienable right to find cats qat disgusting with a right to interfere with the personal choices and pleasures of others.

The risks associated with dogs and cats alcohol and qat are not something we should take lightly, but bans are an excuse to do nothing productive to address a problem, which the government has been doing very well already. Twice they have asked the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) to review the harms of qat, (they are obliged to get expert advice before they ban it), and twice the ACMD has said that a ban would be inappropriate and disproportionate, while making a series of considered recommendations for awareness-raising and community engagement, access to treatment services and improving health standards of qat cafes. While the government has no problems collecting millions in tax on qat imports, it seems reluctant to consider any investment in looking after qat users, except if they are in prison cells.

All right, I think we've chewed over the qat/cat analogy long enough, but there is a serious point to be made here. I got into a little trouble for comparing the risks of death and serious injury from horse-riding and ecstasy, so I should be sure to say that whilst horse-riding really is comparably risky to the class A drug, in terms of acute harm, I expect that khat use is more often seriously problematic than cat-ownership. However, we should be comfortable with the idea of comparing the risks of drug use with other risks we might face: cooking, trampolining, sunbathing or pet ownership. Our drug laws are purportedly there to protect individuals and society from harm – they are not meant to be there to uphold any specific moral values and punish deviance from them. If politicians wish to argue for drug prohibitions on a moral basis, because they think it is obnoxious and dissolute to sit around getting high from leaves or intoxicated by drink, that's fine, let them make the case, and see whether parliament or the electorate have an interest in policing people's personal habits. What they must not be allowed to do is to push a moral agenda against an already marginalised group through laws intended to regulate drugs on the basis of evidence of their harmfulness.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)