The current India tour of Australia has already had a bowling allrounder, a lower-order batsman, miss the T20I series because of a concussion. A key bowler is missing three Tests of the series with a broken arm. An opening batsman has missed out on a potential Test debut because of a hit to his head, which gave him his ninth concussion before the age of 22. All three players were hit by accurate, high-pace short-pitched bowling, which takes extreme skill, and some luck, to keep out.

The concussed bowling allrounder is now back. He scored a fifty at the MCG that frustrated the home side, who have been accustomed to rolling India over once they lose five wickets. India's additions from five-down in their last six innings in Test cricket: 64, 43, 48, 40, 48, 21. In Melbourne, the sixth wicket alone added 121 because this bowling allrounder hung around with his captain, one of only five specialist batsmen, a bold selection by the visiting side after 36 all out.

The fast bowler whose bouncer in the T20I ended up concussing this allrounder goes back to the bouncer plan in the Test. Experts on TV feel he has been too late getting there, that he has not been nasty enough. The allrounder shows he can handle himself, dropping his wrists and head out of the way of a couple of snorters, but he eventually plays a hook and is caught in the deep.

The next few batsmen are much less adept at handling this kind of bowling - the kind of players who have yielded low returns for India batting lower in the order. Bouncer after bouncer follows. One batsman has to call for help after getting hit in the chest. The other is hit twice on the forearm. All told, the bowler bowls 23 consecutive short balls at Nos. 7-9. Welcome to the land of "broken f****** elbows".

****

This is Australia. This is the land of tough, "hard but fair" cricket. This is also the place where there was an exemplary inquest into safety standards in cricket after the tragic death of young Phillip Hughes on a cricket field. Hughes was a specialist batsman, it was not a high-pressure Test match, and he was not facing an express bowler. He was hit in the side of the neck by a bouncer, just where the helmet ends.

It was a moment of awakening in cricket; of realisation that we have been extremely lucky, given the number of blows batsmen take, that we have not had too many such grave injuries. That it needn't be an inept tailender, that it needn't be 150kph, that it needn't be particularly nasty at first look, that any of the large number of bouncers we see and enjoy could be fatal for any of the practitioners of this highly skilled sport.

No. 9: the blow in the Sydney tour game was the ninth time Will Pucovski had been concussed playing cricket Getty Images

Imagine the number of concussions we have missed, now that we know how likely a blow to the head from a fast-paced bouncer is likely to cause one. In 2019, in the aftermath of the Steven Smith concussion, Mark Butcher told ESPNcricinfo's podcast Switch Hit how he faced a barrage from Tino Best and Fidel Edwards in 2004, wore one on the head, went off for bad light, didn't tell anyone how he felt, came back and batted with the same compromised helmet on. He is pretty certain he has batted through concussions. "You just batted on as long as you saw straight."

A concussion is a head injury that causes the head and the brain to shake back and forth quickly, not too unlike a pinball. It can make you dizzy, it can disorient you, it can slow your instincts down, its symptoms can show up at the time of impact or five minutes after, or an hour later, or at any time over the next couple of days. Just imagine the number of players who have continued risking what is potentially often a much graver "second impact", which can be caused in part by slowed instincts because of the first impact.

Australia is the land trying hard to normalise going off when you've had a head injury. It led cricket into instituting concussion substitutes. Six years on from Hughes' death, we are in the middle of a series between two highly skilled pace attacks capable of aiming high-speed, accurate short-pitched bowling at the bodies of batsmen.

Imagine the number of concussions we have missed, now that we know how likely a blow to the head from a fast-paced bouncer is likely to cause one. In 2019, in the aftermath of the Steven Smith concussion, Mark Butcher told ESPNcricinfo's podcast Switch Hit how he faced a barrage from Tino Best and Fidel Edwards in 2004, wore one on the head, went off for bad light, didn't tell anyone how he felt, came back and batted with the same compromised helmet on. He is pretty certain he has batted through concussions. "You just batted on as long as you saw straight."

A concussion is a head injury that causes the head and the brain to shake back and forth quickly, not too unlike a pinball. It can make you dizzy, it can disorient you, it can slow your instincts down, its symptoms can show up at the time of impact or five minutes after, or an hour later, or at any time over the next couple of days. Just imagine the number of players who have continued risking what is potentially often a much graver "second impact", which can be caused in part by slowed instincts because of the first impact.

Australia is the land trying hard to normalise going off when you've had a head injury. It led cricket into instituting concussion substitutes. Six years on from Hughes' death, we are in the middle of a series between two highly skilled pace attacks capable of aiming high-speed, accurate short-pitched bowling at the bodies of batsmen.

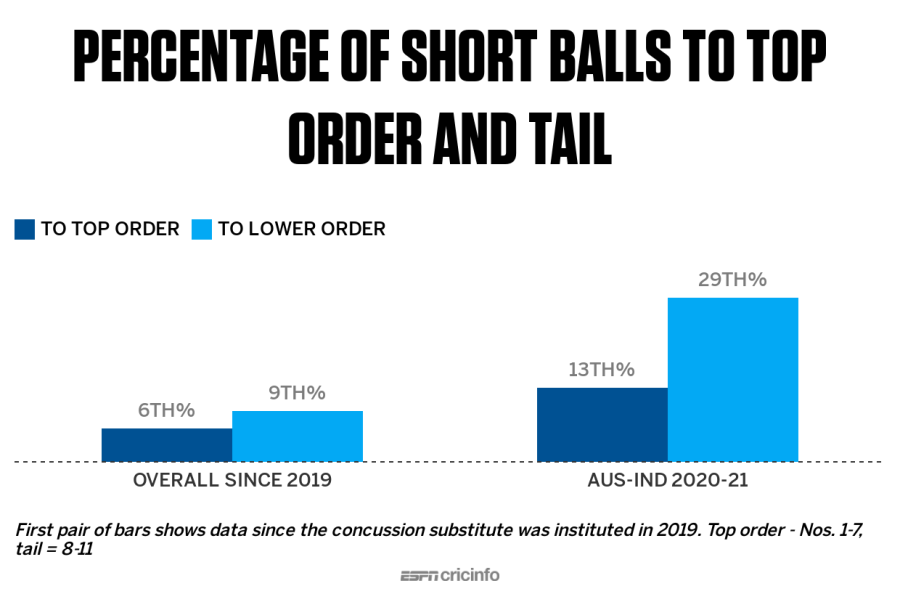

While there is conversation around making cricket safer, the threat for lesser-skilled batsmen is going up: 13% of deliveries from fast bowlers to those batting from Nos. 1 to 7 has been short in this series; for the lesser batsmen, batting from 8 to 11, this number has gone up to a whopping 29%, or roughly two short balls an over. The corresponding numbers in the recently concluded series between New Zealand and West Indies were 9% and 13%, which is still higher than the norm in Test cricket: 6% for batsmen 1 to 7 and 9% for the tail since concussions substitutes were introduced in July 2019.

****

Cricket is a weird sport. If you are a tail-end batsman, you often have to go out and let millions watch you do something you are inept at - sometimes hilariously so. And do it against opponents who are almost lethally good at doing what they are doing. The less you like it, the more you get it.

Opposing fast bowlers have stopped looking after each other now, what with protective equipment improving and lower-order batsmen increasingly placing higher prices on their wickets. When you are hit by a bouncer, you know there are former cricketers, some of whom you grew up idolising, waiting to label you soft should you show pain, let alone walk off.

"You just batted on as long as you saw straight:" Mark Butcher gets hit by one from Tino Best Getty Images

When Ravindra Jadeja, the previously mentioned bowling allrounder, took a concussion substitute in the T20I, the predominant conversation was about the need to watch out against the misuse of the concussion substitute. Perhaps because Jadeja batted on for three more balls after he was hit - which was also a sign that not all teams take concussions seriously enough. Not every batsman has a stem guard at the back of his helmet, an appendage that might have saved Hughes' life.

Mark Taylor's response is a good summation of what the pundits thought: "The concussion rules are there to protect players. If they are abused, there's a chance it will go like the runner's rule. The reason runners were outlawed was because it started to be abused. It's up to the players to make sure they use the concussion sub fairly and responsibly. I'm not suggesting that didn't happen last night."

Taylor is a former Test captain, a former ICC cricket committee member, and a current administrator. He is better informed than many. During India's home season in 2019, when Bangladesh's batsmen were hit again and again in less-than-ideal viewing conditions in a hurriedly organised first day-night Test in India, commentators questioned their courage and called the repeated concussion tests ridiculous.

****

Mitchell Starc is the bowler whose bouncer resulted in the concussion to Jadeja. He is the one who bowled 23 short balls in a row at India's lower-order batsmen. He has had to deal with criticism from former players for being too soft at various points in his career. He saw his batsmen score just 195 after winning the toss in Melbourne, and was part of the bowling group that was asked once again to bail the team out. India batted extremely well, five catches went down, the pitch was easing out a little, and the deficit was growing. There was a microscope over Starc now.

When Ravindra Jadeja, the previously mentioned bowling allrounder, took a concussion substitute in the T20I, the predominant conversation was about the need to watch out against the misuse of the concussion substitute. Perhaps because Jadeja batted on for three more balls after he was hit - which was also a sign that not all teams take concussions seriously enough. Not every batsman has a stem guard at the back of his helmet, an appendage that might have saved Hughes' life.

Mark Taylor's response is a good summation of what the pundits thought: "The concussion rules are there to protect players. If they are abused, there's a chance it will go like the runner's rule. The reason runners were outlawed was because it started to be abused. It's up to the players to make sure they use the concussion sub fairly and responsibly. I'm not suggesting that didn't happen last night."

Taylor is a former Test captain, a former ICC cricket committee member, and a current administrator. He is better informed than many. During India's home season in 2019, when Bangladesh's batsmen were hit again and again in less-than-ideal viewing conditions in a hurriedly organised first day-night Test in India, commentators questioned their courage and called the repeated concussion tests ridiculous.

****

Mitchell Starc is the bowler whose bouncer resulted in the concussion to Jadeja. He is the one who bowled 23 short balls in a row at India's lower-order batsmen. He has had to deal with criticism from former players for being too soft at various points in his career. He saw his batsmen score just 195 after winning the toss in Melbourne, and was part of the bowling group that was asked once again to bail the team out. India batted extremely well, five catches went down, the pitch was easing out a little, and the deficit was growing. There was a microscope over Starc now.

Umesh Yadav gets out of the way of a Starc bouncer. "You don't hit me, I won't hit you" doesn't apply among fast bowlers anymore Getty Images

Test-match cricket is no ordinary workplace. You have to do whatever is within the laws to get your wickets. Almost everyone is so good at what they do that errors have to be prised out, sometimes forced. Every weakness is preyed upon for whatever small advantage it might yield. It is not far-fetched to imagine Will Pucovski, the previously mentioned repeatedly concussed opening batsman, will be peppered if and when he makes his Test debut. This Indian team has fast bowlers who can give as good as they get, and they have got some from the Australian bowlers.

For over after over, fast bowlers do what their bodies are not biomechanically meant to be doing. You have to find a way to get a wicket. The bouncer is a legitimate ploy to get wickets, to mess with the batsman's footwork, to let them know they can't plonk the front foot down and keep driving or defending them, and even to send a message out to the remaining batsmen. That line between bowling bouncers to get wickets and doing it to hurt can get blurred. If you have an awesome power and no one has a way to tell with certainty that if you are always using it with good intent, there are chances you will end up misusing it once in a while.

It might sound extremely cynical, but if a blow to the head is highly likely to get a concussion substitute in, thus putting a front-line bowler out for at least a week and denying the opposition their ideal XI for the next Test, is it that difficult to imagine a fast bowler trying that extra bouncer before going for the full ball? Test match cricket is no ordinary workplace.

****

"I didn't want just that bloke to be scared," Len Pascoe said to me in 2015. "I wanted the guys in the dressing room to be scared too. If you got him scared, that's it. Often when I took wickets, I would get them in batches. One, two, bang. You just hit hard, hit hard."

Pascoe is a man after whom a hospital ward was named in the New South Wales town where he lived. Back then in the 1970s, every Saturday, Bankstown hospital would receive cricket victims in the Thomson-Pascoe ward. (And that despite being told years later by the groundsman at Bankstown that because of Thomson and Pascoe he used to make incredibly flat pitches.)

Test-match cricket is no ordinary workplace. You have to do whatever is within the laws to get your wickets. Almost everyone is so good at what they do that errors have to be prised out, sometimes forced. Every weakness is preyed upon for whatever small advantage it might yield. It is not far-fetched to imagine Will Pucovski, the previously mentioned repeatedly concussed opening batsman, will be peppered if and when he makes his Test debut. This Indian team has fast bowlers who can give as good as they get, and they have got some from the Australian bowlers.

For over after over, fast bowlers do what their bodies are not biomechanically meant to be doing. You have to find a way to get a wicket. The bouncer is a legitimate ploy to get wickets, to mess with the batsman's footwork, to let them know they can't plonk the front foot down and keep driving or defending them, and even to send a message out to the remaining batsmen. That line between bowling bouncers to get wickets and doing it to hurt can get blurred. If you have an awesome power and no one has a way to tell with certainty that if you are always using it with good intent, there are chances you will end up misusing it once in a while.

It might sound extremely cynical, but if a blow to the head is highly likely to get a concussion substitute in, thus putting a front-line bowler out for at least a week and denying the opposition their ideal XI for the next Test, is it that difficult to imagine a fast bowler trying that extra bouncer before going for the full ball? Test match cricket is no ordinary workplace.

****

"I didn't want just that bloke to be scared," Len Pascoe said to me in 2015. "I wanted the guys in the dressing room to be scared too. If you got him scared, that's it. Often when I took wickets, I would get them in batches. One, two, bang. You just hit hard, hit hard."

Pascoe is a man after whom a hospital ward was named in the New South Wales town where he lived. Back then in the 1970s, every Saturday, Bankstown hospital would receive cricket victims in the Thomson-Pascoe ward. (And that despite being told years later by the groundsman at Bankstown that because of Thomson and Pascoe he used to make incredibly flat pitches.)

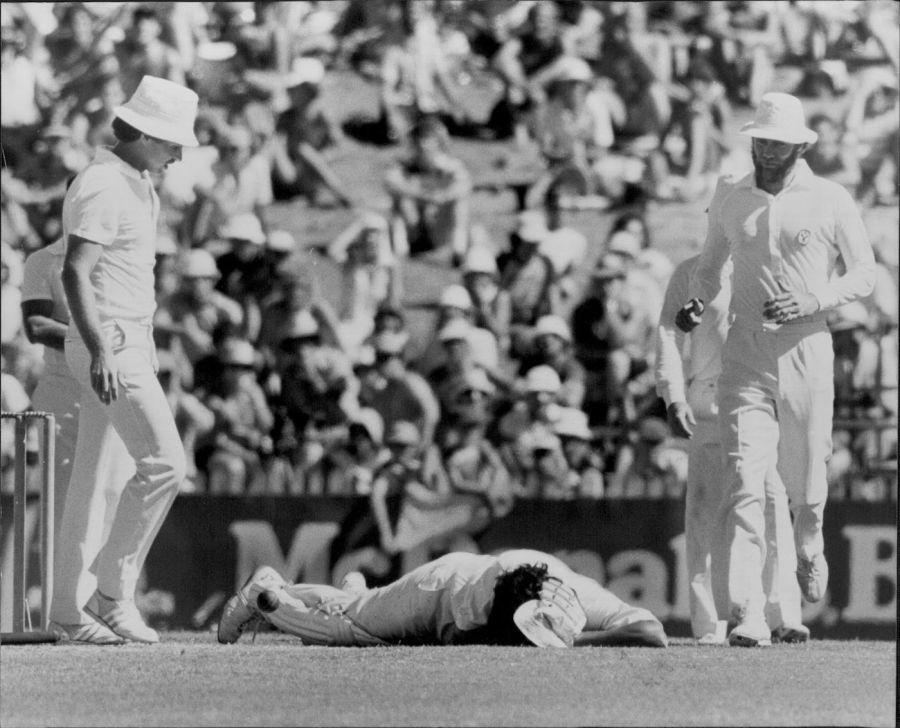

Sandeep Patil is felled by Len Pascoe in Sydney in 1981 Getty Images

Pascoe was a young fast bowler, son of an immigrant brick carter, who grew up with racial abuse. To him, the man standing in the way of everything he wanted was the one across the 22 yards. He would do anything to get him out, and his captains and batsmen loved using him to do that. He bowled in an era when it was commonplace to hear chants of "Lillee Lillee, kill kill" at cricket rounds. In those days, any discussion around player safety was arguably mostly a ploy to neutralise West Indies, who had by then developed a pace battery that could match if not outdo any pace attack blow for blow.

The injuries Pascoe caused concerned him. Once, a batsman, George Griffith of South Australia, told him in a hospital after a day's play that had he been hit half an inch either side of where he had been, he wouldn't probably have been around to accept the apology. When Pascoe next hit a batsman badly - Sutherland's Glenn Bailey in a grade game, who then vomited blood - his mate Thomson had only recently lost his former flat-mate, 22-year-old Martin Bedkober, felled by a blow to the chest while batting in a Queensland grade match.

The young Pascoe kept doing it despite his discomfort, kept rationalising it to himself, comparing it to the risk a policeman or an army man takes, but when, at 32, he hit Sandeep Patil, a blow that knocked the batsman off his feet, he had had enough. He saw Patil stagger off the field, barely conscious, swaying this way and that despite support from the medical staff. Pascoe told his captain, Ian Chappell, he was walking away. Pascoe said Chappell asked him, "What if he hits you for six? Do you think he feels sorry for you?" That kept Pascoe going for another season but his heart was not in it.

Pascoe never injured another batsman. As a coach now, he teaches young bowlers to use the bouncer responsibly: bowl the first one well over the leg stump, only as a fact-finding mission to see where the feet are going. Bowl to get wickets, not to injure batsmen. It is important to instil fear, but it is equally important to not get addicted to instilling that fear.

****

Test cricket in New Zealand is played upside down. As matches progress, the pitches get slower and better to bat on. The best time to bat is the fourth innings. Everywhere else in the world, no matter how green the pitch, you win the toss and bat if no time has been lost to rain before the toss. New Zealand is the only place in the world where you win the toss and bowl first, because dismissals have to be manufactured in the second innings.

Pascoe was a young fast bowler, son of an immigrant brick carter, who grew up with racial abuse. To him, the man standing in the way of everything he wanted was the one across the 22 yards. He would do anything to get him out, and his captains and batsmen loved using him to do that. He bowled in an era when it was commonplace to hear chants of "Lillee Lillee, kill kill" at cricket rounds. In those days, any discussion around player safety was arguably mostly a ploy to neutralise West Indies, who had by then developed a pace battery that could match if not outdo any pace attack blow for blow.

The injuries Pascoe caused concerned him. Once, a batsman, George Griffith of South Australia, told him in a hospital after a day's play that had he been hit half an inch either side of where he had been, he wouldn't probably have been around to accept the apology. When Pascoe next hit a batsman badly - Sutherland's Glenn Bailey in a grade game, who then vomited blood - his mate Thomson had only recently lost his former flat-mate, 22-year-old Martin Bedkober, felled by a blow to the chest while batting in a Queensland grade match.

The young Pascoe kept doing it despite his discomfort, kept rationalising it to himself, comparing it to the risk a policeman or an army man takes, but when, at 32, he hit Sandeep Patil, a blow that knocked the batsman off his feet, he had had enough. He saw Patil stagger off the field, barely conscious, swaying this way and that despite support from the medical staff. Pascoe told his captain, Ian Chappell, he was walking away. Pascoe said Chappell asked him, "What if he hits you for six? Do you think he feels sorry for you?" That kept Pascoe going for another season but his heart was not in it.

Pascoe never injured another batsman. As a coach now, he teaches young bowlers to use the bouncer responsibly: bowl the first one well over the leg stump, only as a fact-finding mission to see where the feet are going. Bowl to get wickets, not to injure batsmen. It is important to instil fear, but it is equally important to not get addicted to instilling that fear.

****

Test cricket in New Zealand is played upside down. As matches progress, the pitches get slower and better to bat on. The best time to bat is the fourth innings. Everywhere else in the world, no matter how green the pitch, you win the toss and bat if no time has been lost to rain before the toss. New Zealand is the only place in the world where you win the toss and bowl first, because dismissals have to be manufactured in the second innings.

Life is nasty, brutish and short when you're facing Neil Wagner Getty Images

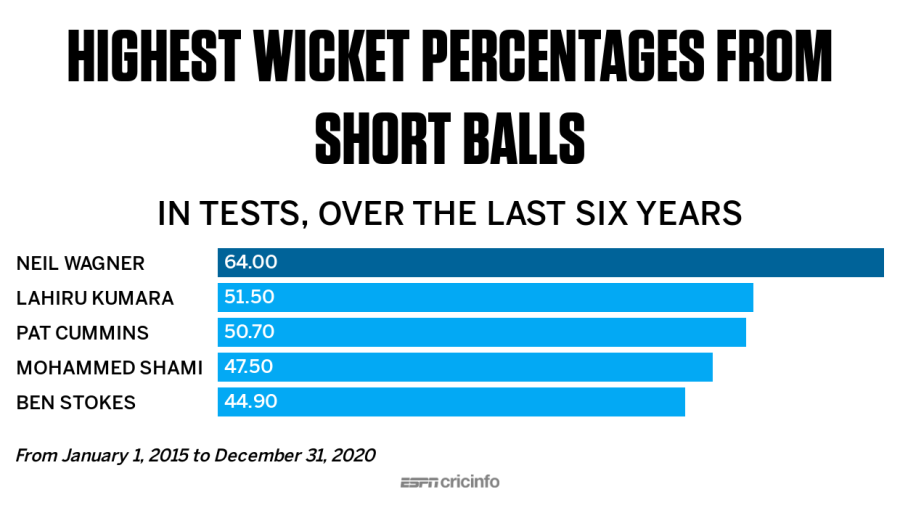

These conditions have given rise to a phenom called Neil Wagner. But for Wagner's style of bowling - persistent short balls between the chest and the head of the batsmen - there would be a high rate of draws in New Zealand. Since his debut, Wagner has bowled more short balls and taken more wickets with them than anyone else. He trains like a madman so that he can keep doing it over extremely long spells.

Two days after Starc possibly flirted with the line between bowling bouncers for wickets and bowling them for the hurt, Wagner goes to work on a dead pitch in the face of a stubborn Pakistan resistance to try to draw the Test. Running in on two broken toes, over an 11-over spell, Wagner bowls bouncer after bouncer from varied angles at varied heights and paces, and finally manages to get the wicket of century-maker Fawad Alam with a short ball from round the wicket.

The tail dig in their heels, and we go into the last hour with two wickets still in hand. Wagner figures the batsmen can block if he keeps pitching it up. So he digs it in short, and gets Shaheen Shah Afridi in the head in the 11th over of his spell. Over the next few overs, Afridi is tested repeatedly for a possible concussion.

This Wagner spell is compelling to watch. One man against the conditions, against his own hurting foot, against stubborn batsmen, trying to win his side a Test match in the dying minutes of the final day. The tail, emboldened by the improved protective equipment batsmen get to wear, braving blows to the body, trying to save a Test match. The fast bowler, fitter and stronger than he has ever been, able to sustain hostility and accuracy over longer spells than ever before.

These conditions have given rise to a phenom called Neil Wagner. But for Wagner's style of bowling - persistent short balls between the chest and the head of the batsmen - there would be a high rate of draws in New Zealand. Since his debut, Wagner has bowled more short balls and taken more wickets with them than anyone else. He trains like a madman so that he can keep doing it over extremely long spells.

Two days after Starc possibly flirted with the line between bowling bouncers for wickets and bowling them for the hurt, Wagner goes to work on a dead pitch in the face of a stubborn Pakistan resistance to try to draw the Test. Running in on two broken toes, over an 11-over spell, Wagner bowls bouncer after bouncer from varied angles at varied heights and paces, and finally manages to get the wicket of century-maker Fawad Alam with a short ball from round the wicket.

The tail dig in their heels, and we go into the last hour with two wickets still in hand. Wagner figures the batsmen can block if he keeps pitching it up. So he digs it in short, and gets Shaheen Shah Afridi in the head in the 11th over of his spell. Over the next few overs, Afridi is tested repeatedly for a possible concussion.

This Wagner spell is compelling to watch. One man against the conditions, against his own hurting foot, against stubborn batsmen, trying to win his side a Test match in the dying minutes of the final day. The tail, emboldened by the improved protective equipment batsmen get to wear, braving blows to the body, trying to save a Test match. The fast bowler, fitter and stronger than he has ever been, able to sustain hostility and accuracy over longer spells than ever before.

ESPNcricinfo Ltd

ESPNcricinfo Ltd****

"The bowling of short-pitched deliveries is dangerous if the bowler's end umpire considers that, taking into consideration the skill of the striker, by their speed, length, height and direction they are likely to inflict physical injury on him/her. The fact that the striker is wearing protective equipment shall be disregarded."

The MCC leaves it to the umpires to decide what is dangerous. In most cases the umpires are professional enough to prevent things from getting bad enough to be visible to those watching from the outside. Often a quiet word when the bowler is walking back to their mark is enough. Yet the times that it does get out of hand, the umpire can call a dangerous delivery a no-ball, followed by a "first and final warning" and suspension from bowling should the bowler repeat the offence. It is near impossible to remember when such a no-ball was called, let alone a suspension.

The one time in recent memory when it did look like it got out of hand was when Brett Lee bowled four straight bouncers at Makhaya Ntini and Nantie Hayward in Adelaide back in 2002. Ntini was hit on the head twice before staggering through for a leg-bye, with Ian Chappell on air observing he was "perhaps a little dazed". After the fourth short ball, which chased Hayward's head as he backed away towards square leg, umpire Simon Taufel had a quiet word, resulting in two full deliveries.

Often under fire from commentators - former players themselves - and fans, umpires can be reluctant to draw any attention to themselves. The common refrain they have to deal with: "They have come to watch us play, not you umpire." Umpires don't want to be seen as overly officious - when it comes to policing player behaviour or in ball management or pitch management or ensuring player safety.

If the umpire steps in in the case of Starc, it will certainly be controversial in this high-profile contest. If he steps in to prevent Wagner from bouncing Afridi, he knows his one quiet word could end up being the difference between a win and a draw for New Zealand. The umpire has to ensure player safety but without compromising the integrity of the contest or attracting vitriol from former players and media. It is an extremely tight rope.

****

Those running the sport stand at a crucial crossroads. A lot of sports - especially those played by teams - have their roots in military training or colonisation. They were originally played to keep troops fit and ready for war, to hone a killer instinct for real war by indulging in a phony war; for voyeuristic entertainment; or to discipline the people of a new country so as to control and spread the right messages among the colonised. The war analogies endure but we have come a long way from sport's original purpose. Player safety standards might need to catch up.

Brett Lee to Makhaya Ntini, 2001: welcome to Adelaide Getty Images

One of the reasons bouncers are such a thrilling spectacle is the real danger they carry. At that pace and that height, you can't always control what is happening. To watch an expert batsman try to tame this force through technique, skill, courage and luck is a rush. There has to be a rush involved in bowling or facing them too. But only till someone gets hurt again, especially knowing as we do now what even a moderate-looking impact can do to a player's health. The rush gives way to unease pretty quickly these days.

Any new regulation that aims to limit this damage will be tricky to enforce. The existing regulations, which limit the number of short balls that are head-high (and not, for instance, chest-high) might need to be looked at too. In the last decade there were two recorded instances of club cricketers not surviving blows to the chest.

At first glance, the idea of regulating the use of bouncers seems ridiculous, given how integral the bouncer is to the game of cricket. There must have been a time, too, when the idea of a concussion substitute must have seemed ridiculous. When it must have been okay for players to compromise their safety by carrying on playing with potential brain injuries.

There will have to be a time when it might not be considered ridiculous for player safety to take precedence over the desire to preserve the bouncer. It seems more a matter of when than if. Any decision will involve carefully examining what the sport will end up losing. A length-ball outswinger might not be as effective if the batsman knows he can keep planting his front foot down to cover the movement. We might end up losing out on a whole genre of bowling: Wagnering, if you will. It will make the umpires' job even more difficult, bringing more subjectivity into it as they rule one bouncer dangerous and another passable.

Then again, do we, and the sport, have it in us to wait for another grave injury - or lawsuits in some countries - before we make that move?

One of the reasons bouncers are such a thrilling spectacle is the real danger they carry. At that pace and that height, you can't always control what is happening. To watch an expert batsman try to tame this force through technique, skill, courage and luck is a rush. There has to be a rush involved in bowling or facing them too. But only till someone gets hurt again, especially knowing as we do now what even a moderate-looking impact can do to a player's health. The rush gives way to unease pretty quickly these days.

Any new regulation that aims to limit this damage will be tricky to enforce. The existing regulations, which limit the number of short balls that are head-high (and not, for instance, chest-high) might need to be looked at too. In the last decade there were two recorded instances of club cricketers not surviving blows to the chest.

At first glance, the idea of regulating the use of bouncers seems ridiculous, given how integral the bouncer is to the game of cricket. There must have been a time, too, when the idea of a concussion substitute must have seemed ridiculous. When it must have been okay for players to compromise their safety by carrying on playing with potential brain injuries.

There will have to be a time when it might not be considered ridiculous for player safety to take precedence over the desire to preserve the bouncer. It seems more a matter of when than if. Any decision will involve carefully examining what the sport will end up losing. A length-ball outswinger might not be as effective if the batsman knows he can keep planting his front foot down to cover the movement. We might end up losing out on a whole genre of bowling: Wagnering, if you will. It will make the umpires' job even more difficult, bringing more subjectivity into it as they rule one bouncer dangerous and another passable.

Then again, do we, and the sport, have it in us to wait for another grave injury - or lawsuits in some countries - before we make that move?