'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label atheism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label atheism. Show all posts

Tuesday, 24 October 2023

Tuesday, 4 July 2023

Tuesday, 6 June 2023

Thursday, 11 June 2020

Monday, 22 October 2018

On Sabarimala - Why are rational, scientific women upset?

By Girish Menon

“I do not wish to join any club that will accept me as a

member” quipped Groucho Marx once. I will pass on this wisdom to women of

menstruating age whose efforts to enter Sabarimala have been stopped by their

own sisters, male priests and political activists.

In essence the Indian Supreme Court has decided in favour of

allowing all women to worship at Sabarimala as failing to do so could be

interpreted as discriminatory and in violation of every Indian’s fundamental

right to equality guaranteed by the constitution.

The recent violence is testimony to the failure of the

Indian state as it could not ensure protection to those women who wished to

worship at Sabarimala. This is a replay of Ayodhya 1992 when a mob destroyed

the Babri Masjid in violation of court strictures.

I have read reports that those opposed to the Supreme Court

verdict in the Sabarimala case have now filed an appeal with the Supreme Court.

This is a welcome move and should have been the first step in their protests

instead of physically stopping women from entering the temple.

In a democracy the legislature is superior to the courts. So

it should have been up to the political activists to pass legislation that

suits their political views. However, such legislation will always be of

secondary status to the fundamental rights of every Indian which can only be

curtailed under special circumstances, if at all.

Tradition

Tradition has been quoted as the main argument to defend the

practices of Sabarimala. Leaders of most denominations use this argument to

protest against demands for reforms. This argument gains most momentum because

of the historical failure to pass a uniform civil code bill that applies to

every Indian uniformly.

In the case of Hindus, The Paliyam Satyagraha in Chendamangalam

in 1947-48 enabled a break with tradition as lower caste Hindus were hereafter allowed

to enter temples. Thus tradition is only a convenient term to fight against

reform and modernity.

Uniting all Hindus

The demographic changes in India

In the book The Global Minotaur the author Yanis Varoufakis

defines the term aporia

–

that state of

intense puzzlement in which we find

ourselves when our certainties fall to pieces ; when suddenly we get caught in

an impasse, at a loss to explain what our eyes can see, our fingers can touch,

our ears can hear. At those rare moments, as our reason valiantly struggles to

fathom what the senses are reporting, our aporia humbles us and readies the

prepared mind for previously unbearable truths.

For Indians the moment of aporia has arrived. Now maybe the best time to introduce the

uniform civil code and ban religious conversions. Else the charge of India

On the other hand, why would modern, rational women with a

scientific bent of mind and a claim that ‘God does not exist’ fight for rights

to worship Ayyappa is something that I have found hard to understand.

Monday, 17 September 2018

What is your brand of atheism?

Arvind Sharma in The Wire.In

The modern world is nothing if not plural in the number of possible world views it offers in terms of religions, creeds and ideologies. The profusion can be quite perplexing, even bewildering. And atheism too is an important component of the cocktail.

The book under review – John Gray’s Seven Types of Atheism – acts like a ‘guide to the perplexed’ in the modern Western world by bestowing the same kind of critical attention to atheism as theologians do to theism, and historians of religion do to the world religions.

In doing so, it identifies seven types of atheism: (1) new atheism, or an atheism which is simply interested in discrediting religion; (2) ‘secular atheism’, better described as secular humanism, which seeks salvation of the world within the world through progress; (3) ‘scientific atheism’, which turns science into a religion – a category in which the author includes ‘evolutionary humanism, Mesmerism, dialectical materialism, and contemporary transhumanism’; (4) ‘political atheism’, a category in which fall what the author considers to be modern political religions such as Jacobinism, Communism, Nazism and contemporary evangelical liberalism; (5) ‘antitheistic atheism’ or misotheism, the kind of atheism characterized by hatred of God of such people as Marquis de Sade, Dostoevsky’s character Ivan Karamazov (in a famous novel) and William Empson; (6) ‘non-humanistic atheism’, of the kind associated with the positions of George Santayana and Joseph Conrad who rejected the idea of a creator God but did not go on to cultivate benevolence towards humanity, so characteristic of secular atheism; and (7) mystical atheism, associated with the names of Schopenhauer, Spinoza, and the Russian thinker Leo Shestov. The author states his position in relation to these seven types candidly; he is repelled (his word) by the first five but feels drawn to the last two.

The seminal insight of the book, in the Western context, is that according “contemporary atheism is a continuation of monotheism by other means”. The author returns to the point again and again so that this insight enables us to examine both religion and atheism in tandem. It is thus an admirable book on atheism in the Western world and is strewn with nuggets such as:

“Scientific inquiry answers a demand for explanation. The practice of religion expresses a need for meaning…”;

“The human mind is programmed for survival, not truth”;

“Science can never close the gap between fact and value”;

“The fundamental conflict in ethics is not between self-interest and general welfare but between general welfare and desires of the moment”;

“It is not only the assertion that ‘moral’ values must take precedence over all others that has been inherited from Christianity. So has the belief that all human beings must live by the same morality”;

“… beliefs that have depended on falsehood need not themselves be false”;

“Some values may be humanly universal – being tortured or persecuted is bad for all human beings. But universal values do not make a universal morality, for these values often conflict with each other”;

“Liberal societies are not templates of a universal political order but instances of a particular form of life. Yet liberals persist in imagining that only ignorance prevents their gospel from being accepted by all of humankind – a vision inherited from Christianity”;

“Causing others to suffer could produce an excitement far beyond any achieved through mere debauchery”;

“Prayer is no less natural than sex, virtue as much as vice”;

“Continuing progress is possible only in technology and the mechanical arts. Progress in this sense may well accelerate as the quality of civilisation declines”;

“Any prospect of a worthwhile life without illusions might itself be an illusion”;

“If Nietzsche shouted the death of God from the rooftops, Arthur Schopenhauer gave the Deity a quiet burial”;

“The liberated individual entered into a realm where the will is silent”;

“Human life… is purposeless striving… But from another point of view this aimless world is pure play”;

“If the human mind mirrors the cosmos, it may be because they are both fundamentally chaotic”; and so on.

Its provocative ideas and brilliant summaries notwithstanding, the book is bound by a limitation; its scope is limited to the West. The author does touch on Buddhism and even Sankhya but only as they have implications for the West; he does not cover Asian ideas of atheism alongside the Western. Neither Confucianism nor Daoism are hung up on a creator god and thus seem to demand attention, if atheism is defined as “the idea of the absence of a creator-god”. Similarly, in Hindu theism, the relation between the universe and the ultimate reality is posited as ontological rather than cosmological.

The concept of atheism also needs to be refined further in relation to Indian religions. In this context it is best to speak of the nontheism of Buddhism (which denies a creator god but not gods as such), and the transtheism of Advaita Vedanta (which accepts a God-like reality but denies it the status of the ultimate reality). In fact, the discussion in this book is perhaps better understood if we invoke some other categories related to the idea of God, such as transcendence and immanence. God is understood as transcendent in the Abrahamic traditions. God no doubt creates the universe but also transcends it; in the Hindu traditions, god is considered both transcendent and immanent – God ‘creates’ the universe and transcends it but also pervades it, just as the number seven transcends the number five but also contains it.

The many atheisms described in the book are really cases of denying the transcendence of god as the ultimate reality and identifying ultimate reality with something immanent in the universe. This enables one to see the atheisms of the West in an even broader light than when described as crypto-monotheisms.

One may conclude the discussion of such a heavy topic on a lighter note. Could one not think of something which is best called ‘devout agnosticism’ as a solution to rampant atheism in the West, if atheism is perceived as a problem? Such would be the situation if one prayed to a God, whose existence had been bracketed by one.

Crying for help from such a God in an emergency, is like crying for help in a less dire situation in which one shouts for help without knowing whether there is any one within earshot. Even the communists in Kerala might have found this possibility useful if the torrential rains filled them with the ‘fear of God’.

The modern world is nothing if not plural in the number of possible world views it offers in terms of religions, creeds and ideologies. The profusion can be quite perplexing, even bewildering. And atheism too is an important component of the cocktail.

The book under review – John Gray’s Seven Types of Atheism – acts like a ‘guide to the perplexed’ in the modern Western world by bestowing the same kind of critical attention to atheism as theologians do to theism, and historians of religion do to the world religions.

In doing so, it identifies seven types of atheism: (1) new atheism, or an atheism which is simply interested in discrediting religion; (2) ‘secular atheism’, better described as secular humanism, which seeks salvation of the world within the world through progress; (3) ‘scientific atheism’, which turns science into a religion – a category in which the author includes ‘evolutionary humanism, Mesmerism, dialectical materialism, and contemporary transhumanism’; (4) ‘political atheism’, a category in which fall what the author considers to be modern political religions such as Jacobinism, Communism, Nazism and contemporary evangelical liberalism; (5) ‘antitheistic atheism’ or misotheism, the kind of atheism characterized by hatred of God of such people as Marquis de Sade, Dostoevsky’s character Ivan Karamazov (in a famous novel) and William Empson; (6) ‘non-humanistic atheism’, of the kind associated with the positions of George Santayana and Joseph Conrad who rejected the idea of a creator God but did not go on to cultivate benevolence towards humanity, so characteristic of secular atheism; and (7) mystical atheism, associated with the names of Schopenhauer, Spinoza, and the Russian thinker Leo Shestov. The author states his position in relation to these seven types candidly; he is repelled (his word) by the first five but feels drawn to the last two.

The seminal insight of the book, in the Western context, is that according “contemporary atheism is a continuation of monotheism by other means”. The author returns to the point again and again so that this insight enables us to examine both religion and atheism in tandem. It is thus an admirable book on atheism in the Western world and is strewn with nuggets such as:

“Scientific inquiry answers a demand for explanation. The practice of religion expresses a need for meaning…”;

“The human mind is programmed for survival, not truth”;

“Science can never close the gap between fact and value”;

“The fundamental conflict in ethics is not between self-interest and general welfare but between general welfare and desires of the moment”;

“It is not only the assertion that ‘moral’ values must take precedence over all others that has been inherited from Christianity. So has the belief that all human beings must live by the same morality”;

“… beliefs that have depended on falsehood need not themselves be false”;

“Some values may be humanly universal – being tortured or persecuted is bad for all human beings. But universal values do not make a universal morality, for these values often conflict with each other”;

“Liberal societies are not templates of a universal political order but instances of a particular form of life. Yet liberals persist in imagining that only ignorance prevents their gospel from being accepted by all of humankind – a vision inherited from Christianity”;

“Causing others to suffer could produce an excitement far beyond any achieved through mere debauchery”;

“Prayer is no less natural than sex, virtue as much as vice”;

“Continuing progress is possible only in technology and the mechanical arts. Progress in this sense may well accelerate as the quality of civilisation declines”;

“Any prospect of a worthwhile life without illusions might itself be an illusion”;

“If Nietzsche shouted the death of God from the rooftops, Arthur Schopenhauer gave the Deity a quiet burial”;

“The liberated individual entered into a realm where the will is silent”;

“Human life… is purposeless striving… But from another point of view this aimless world is pure play”;

“If the human mind mirrors the cosmos, it may be because they are both fundamentally chaotic”; and so on.

Its provocative ideas and brilliant summaries notwithstanding, the book is bound by a limitation; its scope is limited to the West. The author does touch on Buddhism and even Sankhya but only as they have implications for the West; he does not cover Asian ideas of atheism alongside the Western. Neither Confucianism nor Daoism are hung up on a creator god and thus seem to demand attention, if atheism is defined as “the idea of the absence of a creator-god”. Similarly, in Hindu theism, the relation between the universe and the ultimate reality is posited as ontological rather than cosmological.

The concept of atheism also needs to be refined further in relation to Indian religions. In this context it is best to speak of the nontheism of Buddhism (which denies a creator god but not gods as such), and the transtheism of Advaita Vedanta (which accepts a God-like reality but denies it the status of the ultimate reality). In fact, the discussion in this book is perhaps better understood if we invoke some other categories related to the idea of God, such as transcendence and immanence. God is understood as transcendent in the Abrahamic traditions. God no doubt creates the universe but also transcends it; in the Hindu traditions, god is considered both transcendent and immanent – God ‘creates’ the universe and transcends it but also pervades it, just as the number seven transcends the number five but also contains it.

The many atheisms described in the book are really cases of denying the transcendence of god as the ultimate reality and identifying ultimate reality with something immanent in the universe. This enables one to see the atheisms of the West in an even broader light than when described as crypto-monotheisms.

One may conclude the discussion of such a heavy topic on a lighter note. Could one not think of something which is best called ‘devout agnosticism’ as a solution to rampant atheism in the West, if atheism is perceived as a problem? Such would be the situation if one prayed to a God, whose existence had been bracketed by one.

Crying for help from such a God in an emergency, is like crying for help in a less dire situation in which one shouts for help without knowing whether there is any one within earshot. Even the communists in Kerala might have found this possibility useful if the torrential rains filled them with the ‘fear of God’.

Thursday, 26 October 2017

On Militant Atheism - Why the Soviet attempt to stamp out religion failed

Giles Fraser in The Guardian

The Russian revolution had started earlier in February. The tsar had already abdicated. And a provisional bourgeois government had begun to establish itself. But it was the occupation of government buildings in Petrograd, on 25 October 1917, by the Red Guards of the Bolsheviks that marks the beginning of the Communist era proper. And it was from this date that an experiment wholly unprecedented in world history began: the systematic, state-sponsored attempt to eliminate religion. “Militant atheism is not merely incidental or marginal to Communist policy. It is not a side effect, but the central pivot,” wrote Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Lenin compared religion to venereal disease.

Within just weeks of the October revolution, the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment was established to remove all references to religion from school curriculums. In the years that followed, churches and monasteries were destroyed or turned into public toilets. Their land and property was appropriated. Thousands of bishops, monks and clergy were systematically murdered by the security services. Specialist propaganda units were formed, like the League of the Godless. Christian intellectuals were rounded up and sent to camps.

The Soviets had originally believed that when the church had been deprived of its power, religion would quickly wither away. When this did not happen, they redoubled their efforts. In Stalin’s purges of 1936 and 1937 tens of thousands of clergy were rounded up and shot. Under Khrushchev it became illegal to teach religion to your own children. From 1917 to the perestroika period of the 1980s, the more religion persisted, the more the Soviets would seek new and inventive ways to eradicate it. Today the Russian Orthodox churches are packed full. Once the grip of oppression had been released, the faithful returned to church in their millions.

The Soviet experiment manifestly failed. If you want to know why it failed, you could do no better than go along to the British Museum in London next week when the Living with Gods exhibition opens. In collaboration with a BBC Radio 4 series, this exhibition describes some of the myriad ways in which faith expresses itself, using religious objects to examine how people believe rather than what they believe. The first sentence of explanation provided by the British Museum is very telling: “The practice and experience of beliefs are natural to all people.” From prayer flags to a Leeds United kippah, from water jugs to processional chariots, this exhibition tells the story of humanity’s innate and passionate desire to make sense of the world beyond the strictly empirical.

Jill Cook, the exhibition’s curator, remembers going into pre-glasnost churches like Kazan Cathedral in St Petersburg, which had been converted into a museum of atheism. One of the items she has included in the exhibition is a 1989 velvet and silk embroidered image of Christ, for the back of a cope. The person who made this image had no other vestments to work from – they had all been destroyed – other than those she had seen lampooning Christianity in the museum of atheism. What had been a piss-take has been repurposed into a devotional object. Services resumed in Kazan Cathedral in 1992.

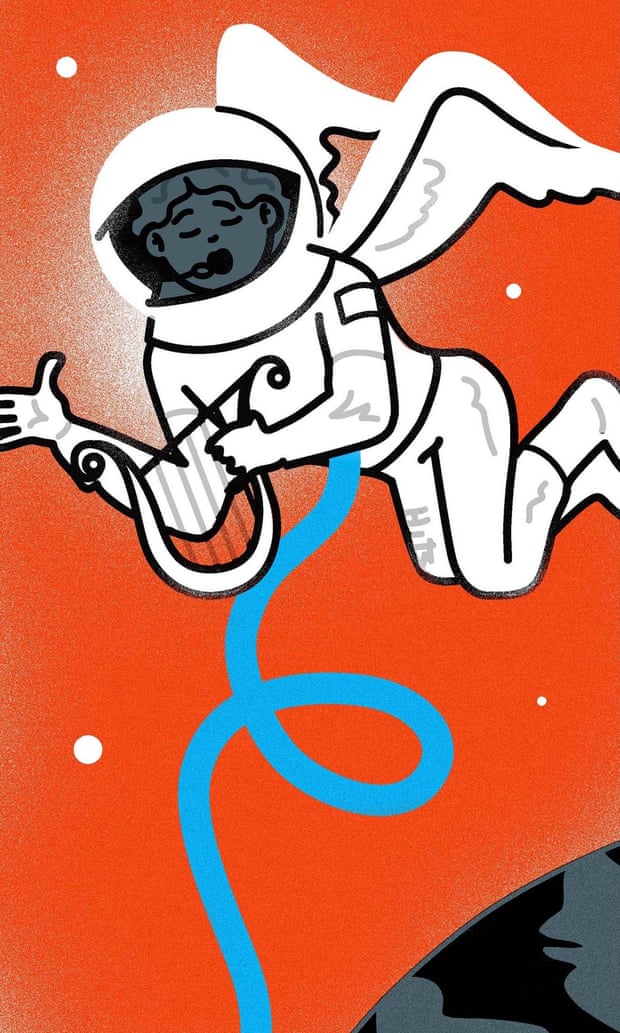

The penultimate image of the exhibition is a 1975 poster of a cheeky-looking cosmonaut walking around in space and declaring: “There is no god.” Below him, on Earth, a church is falling over. This was from the period of so-called scientific atheism.

A poster showing a cosmonaut walking in space and saying: ‘There is no god.’ By Vladimir Menshikow, 1975. Photograph: British Museum

But there is one last exhibit to go. Round the corner, a glass case contains small model boats with burnt matchsticks in them representing people huddled together. And two tiny shirts that had been used as shrouds for drowned children. At the side of them is a small cross, made from the wood of a ship that was wrecked off the Italian island of Lampedusa on 11 October 2013. The ship contained Somali and Eritrean Christian refugees, fleeing poverty and persecution. Francesco Tuccio, the local Lampedusa carpenter, desperately wanted to do something for them, in whatever way he could. So he did all he knew and made them a cross. Just like a famous carpenter before him, I suppose. And what this exhibition demonstrates is that nothing – not decades of propaganda nor state-sponsored terror – will be able to quash that instinct from human life.

The Russian revolution had started earlier in February. The tsar had already abdicated. And a provisional bourgeois government had begun to establish itself. But it was the occupation of government buildings in Petrograd, on 25 October 1917, by the Red Guards of the Bolsheviks that marks the beginning of the Communist era proper. And it was from this date that an experiment wholly unprecedented in world history began: the systematic, state-sponsored attempt to eliminate religion. “Militant atheism is not merely incidental or marginal to Communist policy. It is not a side effect, but the central pivot,” wrote Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Lenin compared religion to venereal disease.

Within just weeks of the October revolution, the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment was established to remove all references to religion from school curriculums. In the years that followed, churches and monasteries were destroyed or turned into public toilets. Their land and property was appropriated. Thousands of bishops, monks and clergy were systematically murdered by the security services. Specialist propaganda units were formed, like the League of the Godless. Christian intellectuals were rounded up and sent to camps.

The Soviets had originally believed that when the church had been deprived of its power, religion would quickly wither away. When this did not happen, they redoubled their efforts. In Stalin’s purges of 1936 and 1937 tens of thousands of clergy were rounded up and shot. Under Khrushchev it became illegal to teach religion to your own children. From 1917 to the perestroika period of the 1980s, the more religion persisted, the more the Soviets would seek new and inventive ways to eradicate it. Today the Russian Orthodox churches are packed full. Once the grip of oppression had been released, the faithful returned to church in their millions.

The Soviet experiment manifestly failed. If you want to know why it failed, you could do no better than go along to the British Museum in London next week when the Living with Gods exhibition opens. In collaboration with a BBC Radio 4 series, this exhibition describes some of the myriad ways in which faith expresses itself, using religious objects to examine how people believe rather than what they believe. The first sentence of explanation provided by the British Museum is very telling: “The practice and experience of beliefs are natural to all people.” From prayer flags to a Leeds United kippah, from water jugs to processional chariots, this exhibition tells the story of humanity’s innate and passionate desire to make sense of the world beyond the strictly empirical.

Jill Cook, the exhibition’s curator, remembers going into pre-glasnost churches like Kazan Cathedral in St Petersburg, which had been converted into a museum of atheism. One of the items she has included in the exhibition is a 1989 velvet and silk embroidered image of Christ, for the back of a cope. The person who made this image had no other vestments to work from – they had all been destroyed – other than those she had seen lampooning Christianity in the museum of atheism. What had been a piss-take has been repurposed into a devotional object. Services resumed in Kazan Cathedral in 1992.

The penultimate image of the exhibition is a 1975 poster of a cheeky-looking cosmonaut walking around in space and declaring: “There is no god.” Below him, on Earth, a church is falling over. This was from the period of so-called scientific atheism.

A poster showing a cosmonaut walking in space and saying: ‘There is no god.’ By Vladimir Menshikow, 1975. Photograph: British Museum

But there is one last exhibit to go. Round the corner, a glass case contains small model boats with burnt matchsticks in them representing people huddled together. And two tiny shirts that had been used as shrouds for drowned children. At the side of them is a small cross, made from the wood of a ship that was wrecked off the Italian island of Lampedusa on 11 October 2013. The ship contained Somali and Eritrean Christian refugees, fleeing poverty and persecution. Francesco Tuccio, the local Lampedusa carpenter, desperately wanted to do something for them, in whatever way he could. So he did all he knew and made them a cross. Just like a famous carpenter before him, I suppose. And what this exhibition demonstrates is that nothing – not decades of propaganda nor state-sponsored terror – will be able to quash that instinct from human life.

Saturday, 9 April 2016

Sunday, 13 March 2016

Are we ready to confront death without religion?

A rise in atheist funerals shows that fewer of us need to rely on faith when confronted with mortality

Adam Lee in The Guardian

For centuries, the Christian church wrote the script for how westerners deal with death. There was the deathbed confession, the last rites, the pallbearers, the obligatory altar call, the burial ceremony, the stone, the angels-and-harps imagery. Yet that archaic and stereotypical vision of death, like a mossy and weather-worn statue, is crumbling – and in its place, something new and better has a chance to grow.

Traditional funerals and burials are declining in popularity (to the point where churches are bemoaning the trend), in favor of alternatives like green burial and cremation. Personalized humanist funerals and secular celebrants are becoming more common, echoing a trend that’s also occurring with weddings.

As younger generations turn away from religion, the US is slowly but surely becoming more secular. As mortician and “good death” advocate Caitlin Doughty writes in her book, Smoke Gets In Your Eyes & Other Lessons from the Crematory, America is seeing a sea-change in traditions and rituals surrounding mortality.

Doughty and others see this shift not as something to be lamented, but to be embraced. Instead of following a script that’s been written for us, we can create our own customs and choose for ourselves how we want to be remembered. We can design funerals that emphasize the good we did, the moments that made our lives meaningful and the lessons we’d like to pass on.

Rather than the same handful of biblical passages, we can have readings from any book, poem or song in the whole broad tapestry of human culture. Rather than mourning, gloom and sermons on sin, we can have ceremonies that are joyful celebrations of the deceased person’s life.

But the rise of humanism isn’t just influencing what funerals look like; it’s changing how we die. For ages, when the church’s word was law, suicide was deemed a mortal sin. Even today, studies find that more fervent religious devotion correlates to more desire for aggressive and medically futile end-of-life intervention, not less.

The most famous case in recent years was Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old woman with terminal brain cancer who ended her life in 2014 under Oregon’s death-with-dignity law. Maynard’s story put a sympathetic public face on the right-to-die movement, which proved decisive when California Governor Jerry Brown, a former Jesuit seminarian, signed a similar bill the next year despite heavy pressure from religious groups. He, too, cited the value of autonomy and freedom from suffering:

“In the end, I was left to reflect on what I would want in the face of my own death,” Brown wrote in a signing message. “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain” he added.

In California and elsewhere, the staunchest adversaries of the right to die are churches and religious believers who assert that the time, place and manner of each person’s death is chosen by God, and that we have no right to change that regardless of the human cost.

And yet, almost without notice, that’s become a minority position. Gallup polls now find that as many as 70% of Americans now support a right to aid in dying. This position entails that, when people are suffering without hope of recovery, they should be allowed to end their lives painlessly, with medical help, at a time of their choosing.

This, too, is a deeply humanist conception of death. It springs from the idea that needless suffering is the greatest evil there is and that autonomy is the supreme value. If we’re the ultimate owners of our own lives, then we have the right to lay them down when we judge they’ve become unbearable.

Even as religious trappings linger in our rituals and attitudes around death, society is coming to adopt the humanist viewpoint on mortality, neither fearing nor denying it, but gracefully accepting it as an inevitable part of the human experience. The sooner we bury our religious past, the better.

Adam Lee in The Guardian

For centuries, the Christian church wrote the script for how westerners deal with death. There was the deathbed confession, the last rites, the pallbearers, the obligatory altar call, the burial ceremony, the stone, the angels-and-harps imagery. Yet that archaic and stereotypical vision of death, like a mossy and weather-worn statue, is crumbling – and in its place, something new and better has a chance to grow.

Traditional funerals and burials are declining in popularity (to the point where churches are bemoaning the trend), in favor of alternatives like green burial and cremation. Personalized humanist funerals and secular celebrants are becoming more common, echoing a trend that’s also occurring with weddings.

As younger generations turn away from religion, the US is slowly but surely becoming more secular. As mortician and “good death” advocate Caitlin Doughty writes in her book, Smoke Gets In Your Eyes & Other Lessons from the Crematory, America is seeing a sea-change in traditions and rituals surrounding mortality.

Doughty and others see this shift not as something to be lamented, but to be embraced. Instead of following a script that’s been written for us, we can create our own customs and choose for ourselves how we want to be remembered. We can design funerals that emphasize the good we did, the moments that made our lives meaningful and the lessons we’d like to pass on.

Rather than the same handful of biblical passages, we can have readings from any book, poem or song in the whole broad tapestry of human culture. Rather than mourning, gloom and sermons on sin, we can have ceremonies that are joyful celebrations of the deceased person’s life.

But the rise of humanism isn’t just influencing what funerals look like; it’s changing how we die. For ages, when the church’s word was law, suicide was deemed a mortal sin. Even today, studies find that more fervent religious devotion correlates to more desire for aggressive and medically futile end-of-life intervention, not less.

The most famous case in recent years was Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old woman with terminal brain cancer who ended her life in 2014 under Oregon’s death-with-dignity law. Maynard’s story put a sympathetic public face on the right-to-die movement, which proved decisive when California Governor Jerry Brown, a former Jesuit seminarian, signed a similar bill the next year despite heavy pressure from religious groups. He, too, cited the value of autonomy and freedom from suffering:

“In the end, I was left to reflect on what I would want in the face of my own death,” Brown wrote in a signing message. “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain” he added.

In California and elsewhere, the staunchest adversaries of the right to die are churches and religious believers who assert that the time, place and manner of each person’s death is chosen by God, and that we have no right to change that regardless of the human cost.

And yet, almost without notice, that’s become a minority position. Gallup polls now find that as many as 70% of Americans now support a right to aid in dying. This position entails that, when people are suffering without hope of recovery, they should be allowed to end their lives painlessly, with medical help, at a time of their choosing.

This, too, is a deeply humanist conception of death. It springs from the idea that needless suffering is the greatest evil there is and that autonomy is the supreme value. If we’re the ultimate owners of our own lives, then we have the right to lay them down when we judge they’ve become unbearable.

Even as religious trappings linger in our rituals and attitudes around death, society is coming to adopt the humanist viewpoint on mortality, neither fearing nor denying it, but gracefully accepting it as an inevitable part of the human experience. The sooner we bury our religious past, the better.

Saturday, 24 October 2015

My atheism does not make me superior to believers. It's a leap of faith too

Ijeoma Olua in The Guardian

I don’t believe in a higher power, but the fact we’ve never proven there isn’t one means there could be a God.

There are many different ways in which people come to atheism. Many come to it in their early adult years, after a childhood in the church. Some are raised in atheism by atheist parents. Some come to atheism after years of religious study. I came to atheism the way that many Christians come to Christianity – through faith.

I was six years old, sitting in my frilly yellow Easter dress, throwing black jelly beans out into the yard, when my mom explained the story of Easter to me. She explained Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection as the son of God, going into great detail. And when she was finished telling me the story that had been a foundation of her faith for the majority of her life, I looked at her and said: “I don’t think that really happened.”

I didn’t come to this conclusion because the story of a man waking from the dead made no sense – I wasn’t an overly analytical child. I still enthusiastically believed in Santa Claus and the Easter bunny. But when I searched myself for any sense of belief in a higher power, it just wasn’t there. I wanted it to be there – how comforting to have a God. But it wasn’t there, and it isn’t to this day.

The same confidence that many of my friends have in the belief that Jesus walks with them is the confidence that I have that nobody walks with me. The cold truth that when I die I will cease to exist in anything but the memory of those I leave behind, that those I love who leave are lost forever, is always with me.

These are my truths. I don’t like these truths. As a mother, I’d give anything to believe that if anything were to happen to my children they would live forever in the kingdom of a loving God. But I don’t believe that.

But my conviction that there is no God is nonetheless a leap of faith. Just as we have been unable to prove there is a God, we have also been unable to prove that there isn’t one. The feeling that I have in my being that there is no God is what I go by, but I’m not deluded into thinking that feeling is in any way more factual than the deep conviction by theists that God exists.

I keep this fact in mind – that my atheism is a leap of faith – because otherwise it’s easy to get cocky. It’s easy to look at acts of terror committed in the names of different gods, debates about the role of women in various churches, unfamiliar and elaborate religious rules and rituals and think, look at these foolish religious folk. It’s easy to view religion as the root of society’s ills.

But atheism as a faith is quickly catching up in its embrace of divisive and oppressive attitudes. We have websites dedicated to insulting Islam and Christianity. We have famous atheist thought-leaders spouting misogyny and calling for the profiling of Muslims. As a black atheist, I encounter just as much racism amongst other atheists as anywhere else. We have hundreds of thousands of atheists blindly following atheist leaders like Richard Dawkins, hurling insults and even threats at those who dare question them.

Look through new atheist websites and twitter feeds. You’ll see the same hatred and bigotry that theists have been spouting against other theists for millennia. But when confronted about this bigotry, we say “But I feel this way about all religion,” as if that somehow makes it better. But our belief that we are right while everyone else is wrong; our belief that our atheism is more moral; our belief that others are lost: none of it is original.

Perhaps this is not religion, but human nature. Perhaps when left to our own devices, we jockey for power by creating an “other” and rallying against it. Perhaps we’re all part of a system that creates hierarchies based on class, gender, race and ethnicity because it’s the easiest way for the few to overpower the many. Perhaps we all fall in line because we look for any social system – be it Christianity, Islam, socialism, atheism – to make sense of it all and to feel like we matter in a world that shows time and time again that we don’t.

If we truly want to free ourselves from the racist, sexist, classist, homophobic tendencies of society, we need to go beyond religion. Yes, religion does need to be examined and debated regularly and fervently. But we also need to examine our school systems, our medical systems, our economic systems, our environmental policies.

Faith is not the enemy, and words in a book are not responsible for the atrocities we commit as human beings. We need to constantly examine and expose our nature as pack animals who are constantly trying to define the other in order to feel safe through all of the systems we build in society. Only then will we be as free from dogma as we atheists claim to be.

There are many different ways in which people come to atheism. Many come to it in their early adult years, after a childhood in the church. Some are raised in atheism by atheist parents. Some come to atheism after years of religious study. I came to atheism the way that many Christians come to Christianity – through faith.

I was six years old, sitting in my frilly yellow Easter dress, throwing black jelly beans out into the yard, when my mom explained the story of Easter to me. She explained Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection as the son of God, going into great detail. And when she was finished telling me the story that had been a foundation of her faith for the majority of her life, I looked at her and said: “I don’t think that really happened.”

I didn’t come to this conclusion because the story of a man waking from the dead made no sense – I wasn’t an overly analytical child. I still enthusiastically believed in Santa Claus and the Easter bunny. But when I searched myself for any sense of belief in a higher power, it just wasn’t there. I wanted it to be there – how comforting to have a God. But it wasn’t there, and it isn’t to this day.

The same confidence that many of my friends have in the belief that Jesus walks with them is the confidence that I have that nobody walks with me. The cold truth that when I die I will cease to exist in anything but the memory of those I leave behind, that those I love who leave are lost forever, is always with me.

These are my truths. I don’t like these truths. As a mother, I’d give anything to believe that if anything were to happen to my children they would live forever in the kingdom of a loving God. But I don’t believe that.

But my conviction that there is no God is nonetheless a leap of faith. Just as we have been unable to prove there is a God, we have also been unable to prove that there isn’t one. The feeling that I have in my being that there is no God is what I go by, but I’m not deluded into thinking that feeling is in any way more factual than the deep conviction by theists that God exists.

I keep this fact in mind – that my atheism is a leap of faith – because otherwise it’s easy to get cocky. It’s easy to look at acts of terror committed in the names of different gods, debates about the role of women in various churches, unfamiliar and elaborate religious rules and rituals and think, look at these foolish religious folk. It’s easy to view religion as the root of society’s ills.

But atheism as a faith is quickly catching up in its embrace of divisive and oppressive attitudes. We have websites dedicated to insulting Islam and Christianity. We have famous atheist thought-leaders spouting misogyny and calling for the profiling of Muslims. As a black atheist, I encounter just as much racism amongst other atheists as anywhere else. We have hundreds of thousands of atheists blindly following atheist leaders like Richard Dawkins, hurling insults and even threats at those who dare question them.

Look through new atheist websites and twitter feeds. You’ll see the same hatred and bigotry that theists have been spouting against other theists for millennia. But when confronted about this bigotry, we say “But I feel this way about all religion,” as if that somehow makes it better. But our belief that we are right while everyone else is wrong; our belief that our atheism is more moral; our belief that others are lost: none of it is original.

Perhaps this is not religion, but human nature. Perhaps when left to our own devices, we jockey for power by creating an “other” and rallying against it. Perhaps we’re all part of a system that creates hierarchies based on class, gender, race and ethnicity because it’s the easiest way for the few to overpower the many. Perhaps we all fall in line because we look for any social system – be it Christianity, Islam, socialism, atheism – to make sense of it all and to feel like we matter in a world that shows time and time again that we don’t.

If we truly want to free ourselves from the racist, sexist, classist, homophobic tendencies of society, we need to go beyond religion. Yes, religion does need to be examined and debated regularly and fervently. But we also need to examine our school systems, our medical systems, our economic systems, our environmental policies.

Faith is not the enemy, and words in a book are not responsible for the atrocities we commit as human beings. We need to constantly examine and expose our nature as pack animals who are constantly trying to define the other in order to feel safe through all of the systems we build in society. Only then will we be as free from dogma as we atheists claim to be.

Saturday, 8 August 2015

Rediscovering God with Rupert Sheldrake

Rediscovering God by Rupert Sheldrake

Also watch

The Science Delusion by Rupert Sheldrake

Rupert Sheldrake - The Science Delusion: Why Materialism is not the Answer

Friday, 17 April 2015

Tuesday, 3 March 2015

What scares the new atheists: The vocal fervour of today’s missionary atheism conceals a panic that religion is not only refusing to decline – but in fact flourishing

John Gray in The Guardian

In 1929, the Thinker’s Library, a series established by the Rationalist Press Association to advance secular thinking and counter the influence of religion in Britain, published an English translation of the German biologist Ernst Haeckel’s 1899 book The Riddle of the Universe. Celebrated as “the German Darwin”, Haeckel was one of the most influential public intellectuals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century; The Riddle of the Universe sold half a million copies in Germany alone, and was translated into dozens of other languages. Hostile to Jewish and Christian traditions, Haeckel devised his own “religion of science” called Monism, which incorporated an anthropology that divided the human species into a hierarchy of racial groups. Though he died in 1919, before the Nazi Party had been founded, his ideas, and widespread influence in Germany, unquestionably helped to create an intellectual climate in which policies of racial slavery and genocide were able to claim a basis in science.

The Thinker’s Library also featured works by Julian Huxley, grandson of TH Huxley, the Victorian biologist who was known as “Darwin’s bulldog” for his fierce defence of evolutionary theory. A proponent of “evolutionary humanism”, which he described as “religion without revelation”, Julian Huxley shared some of Haeckel’s views, including advocacy of eugenics. In 1931, Huxley wrote that there was “a certain amount of evidence that the negro is an earlier product of human evolution than the Mongolian or the European, and as such might be expected to have advanced less, both in body and mind”. Statements of this kind were then commonplace: there were many in the secular intelligentsia – including HG Wells, also a contributor to the Thinker’s Library – who looked forward to a time when “backward” peoples would be remade in a western mould or else vanish from the world.

But by the late 1930s, these views were becoming suspect: already in 1935, Huxley admitted that the concept of race was “hardly definable in scientific terms”. While he never renounced eugenics, little was heard from him on the subject after the second world war. The science that pronounced western people superior was bogus – but what shifted Huxley’s views wasn’t any scientific revelation: it was the rise of Nazism, which revealed what had been done under the aegis of Haeckel-style racism.

It has often been observed that Christianity follows changing moral fashions, all the while believing that it stands apart from the world. The same might be said, with more justice, of the prevalent version of atheism. If an earlier generation of unbelievers shared the racial prejudices of their time and elevated them to the status of scientific truths, evangelical atheists do the same with the liberal values to which western societies subscribe today – while looking with contempt upon “backward” cultures that have not abandoned religion. The racial theories promoted by atheists in the past have been consigned to the memory hole – and today’s most influential atheists would no more endorse racist biology than they would be seen following the guidance of an astrologer. But they have not renounced the conviction that human values must be based in science; now it is liberal values which receive that accolade. There are disputes, sometimes bitter, over how to define and interpret those values, but their supremacy is hardly ever questioned. For 21st century atheist missionaries, being liberal and scientific in outlook are one and the same.

It’s a reassuringly simple equation. In fact there are no reliable connections – whether in logic or history – between atheism, science and liberal values. When organised as a movement and backed by the power of the state, atheist ideologies have been an integral part of despotic regimes that also claimed to be based in science, such as the former Soviet Union. Many rival moralities and political systems – most of them, to date, illiberal – have attempted to assert a basis in science. All have been fraudulent and ephemeral. Yet the attempt continues in atheist movements today, which claim that liberal values can be scientifically validated and are therefore humanly universal.

Fortunately, this type of atheism isn’t the only one that has ever existed. There have been many modern atheisms, some of them more cogent and more intellectually liberating than the type that makes so much noise today. Campaigning atheism is a missionary enterprise, aiming to convert humankind to a particular version of unbelief; but not all atheists have been interested in propagating a new gospel, and some have been friendly to traditional faiths.

Evangelical atheists today view liberal values as part of an emerging global civilisation; but not all atheists, even when they have been committed liberals, have shared this comforting conviction. Atheism comes in many irreducibly different forms, among which the variety being promoted at the present time looks strikingly banal and parochial.

In itself, atheism is an entirely negative position. In pagan Rome, “atheist” (from the Greek atheos) meant anyone who refused to worship the established pantheon of deities. The term was applied to Christians, who not only refused to worship the gods of the pantheon but demanded exclusive worship of their own god. Many non-western religions contain no conception of a creator-god – Buddhism and Taoism, in some of their forms, are atheist religions of this kind – and many religions have had no interest in proselytising. In modern western contexts, however, atheism and rejection of monotheism are practically interchangeable. Roughly speaking, an atheist is anyone who has no use for the concept of God – the idea of a divine mind, which has created humankind and embodies in a perfect form the values that human beings cherish and strive to realise. Many who are atheists in this sense (including myself) regard the evangelical atheism that has emerged over the past few decades with bemusement. Why make a fuss over an idea that has no sense for you? There are untold multitudes who have no interest in waging war on beliefs that mean nothing to them. Throughout history, many have been happy to live their lives without bothering about ultimate questions. This sort of atheism is one of the perennial responses to the experience of being human.

As an organised movement, atheism is never non-committal in this way. It always goes with an alternative belief-system – typically, a set of ideas that serves to show the modern west is the high point of human development. In Europe from the late 19th century until the second world war, this was a version of evolutionary theory that marked out western peoples as being the most highly evolved. Around the time Haeckel was promoting his racial theories, a different theory of western superiority was developed by Marx. While condemning liberal societies and prophesying their doom, Marx viewed them as the high point of human development to date. (This is why he praised British colonialism in India as an essentially progressive development.) If Marx had serious reservations about Darwinism – and he did – it was because Darwin’s theory did not frame evolution as a progressive process.

The predominant varieties of atheist thinking, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, aimed to show that the secular west is the model for a universal civilisation. The missionary atheism of the present time is a replay of this theme; but the west is in retreat today, and beneath the fervour with which this atheism assaults religion there is an unmistakable mood of fear and anxiety. To a significant extent, the new atheism is the expression of a liberal moral panic.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Illustration by Christoph Hitz

Sam Harris, the American neuroscientist and author of The End of Faith: Religion, Terror and the Future of Reason (2004) and The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Moral Values (2010), who was arguably the first of the “new atheists”, illustrates this point. Following many earlier atheist ideologues, he wants a “scientific morality”; but whereas earlier exponents of this sort of atheism used science to prop up values everyone would now agree were illiberal, Harris takes for granted that what he calls a “science of good and evil” cannot be other than liberal in content. (Not everyone will agree with Harris’s account of liberal values, which appears to sanction the practice of torture: “Given what many believe are the exigencies of our war on terrorism,” he wrote in 2004, “the practice of torture, in certain circumstances, would seem to be not only permissible but necessary.”)

Harris’s militancy in asserting these values seems to be largely a reaction to Islamist terrorism. For secular liberals of his generation, the shock of the 11 September attacks went beyond the atrocious loss of life they entailed. The effect of the attacks was to place a question mark over the belief that their values were spreading – slowly, and at times fitfully, but in the long run irresistibly – throughout the world. As society became ever more reliant on science, they had assumed, religion would inexorably decline. No doubt the process would be bumpy, and pockets of irrationality would linger on the margins of modern life; but religion would dwindle away as a factor in human conflict. The road would be long and winding. But the grand march of secular reason would continue, with more and more societies joining the modern west in marginalising religion. Someday, religious belief would be no more important than personal hobbies or ethnic cuisines.

Today, it’s clear that no grand march is under way. The rise of violent jihadism is only the most obvious example of a rejection of secular life. Jihadist thinking comes in numerous varieties, mixing strands from 20th century ideologies, such as Nazism and Leninism, with elements deriving from the 18th century Wahhabist Islamic fundamentalist movement. What all Islamist movements have in common is a categorical rejection of any secular realm. But the ongoing reversal in secularisation is not a peculiarly Islamic phenomenon.

The resurgence of religion is a worldwide development. Russian Orthodoxy is stronger than it has been for over a century, while China is the scene of a reawakening of its indigenous faiths and of underground movements that could make it the largest Christian country in the world by the end of this century. Despite tentative shifts in opinion that have been hailed as evidence it is becoming less pious, the US remains massively and pervasively religious – it’s inconceivable that a professed unbeliever could become president, for example.

For secular thinkers, the continuing vitality of religion calls into question the belief that history underpins their values. To be sure, there is disagreement as to the nature of these values. But pretty well all secular thinkers now take for granted that modern societies must in the end converge on some version of liberalism. Never well founded, this assumption is today clearly unreasonable. So, not for the first time, secular thinkers look to science for a foundation for their values.

It’s probably just as well that the current generation of atheists seems to know so little of the longer history of atheist movements. When they assert that science can bridge fact and value, they overlook the many incompatible value-systems that have been defended in this way. There is no more reason to think science can determine human values today than there was at the time of Haeckel or Huxley. None of the divergent values that atheists have from time to time promoted has any essential connection with atheism, or with science. How could any increase in scientific knowledge validate values such as human equality and personal autonomy? The source of these values is not science. In fact, as the most widely-read atheist thinker of all time argued, these quintessential liberal values have their origins in monotheism.

* * *

The new atheists rarely mention Friedrich Nietzsche, and when they do it is usually to dismiss him. This can’t be because Nietzsche’s ideas are said to have inspired the Nazi cult of racial inequality – an unlikely tale, given that the Nazis claimed their racism was based in science. The reason Nietzsche has been excluded from the mainstream of contemporary atheist thinking is that he exposed the problem atheism has with morality. It’s not that atheists can’t be moral – the subject of so many mawkish debates. The question is which morality an atheist should serve.

It’s a familiar question in continental Europe, where a number of thinkers have explored the prospects of a “difficult atheism” that doesn’t take liberal values for granted. It can’t be said that anything much has come from this effort. Georges Bataille’s postmodern project of “atheology” didn’t produce the godless religion he originally intended, or any coherent type of moral thinking. But at least Bataille, and other thinkers like him, understood that when monotheism has been left behind morality can’t go on as before. Among other things, the universal claims of liberal morality become highly questionable.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Illustration by Christoph Hitz

It’s impossible to read much contemporary polemic against religion without the impression that for the “new atheists” the world would be a better place if Jewish and Christian monotheism had never existed. If only the world wasn’t plagued by these troublesome God-botherers, they are always lamenting, liberal values would be so much more secure. Awkwardly for these atheists, Nietzsche understood that modern liberalism was a secular incarnation of these religious traditions. As a classical scholar, he recognised that a mystical Greek faith in reason had shaped the cultural matrix from which modern liberalism emerged. Some ancient Stoics defended the ideal of a cosmopolitan society; but this was based in the belief that humans share in the Logos, an immortal principle of rationality that was later absorbed into the conception of God with which we are familiar. Nietzsche was clear that the chief sources of liberalism were in Jewish and Christian theism: that is why he was so bitterly hostile to these religions. He was an atheist in large part because he rejected liberal values.

To be sure, evangelical unbelievers adamantly deny that liberalism needs any support from theism. If they are philosophers, they will wheel out their rusty intellectual equipment and assert that those who think liberalism relies on ideas and beliefs inherited from religion are guilty of a genetic fallacy. Canonical liberal thinkers such as John Locke and Immanuel Kant may have been steeped in theism; but ideas are not falsified because they originate in errors. The far-reaching claims these thinkers have made for liberal values can be detached from their theistic beginnings; a liberal morality that applies to all human beings can be formulated without any mention of religion. Or so we are continually being told. The trouble is that it’s hard to make any sense of the idea of a universal morality without invoking an understanding of what it is to be human that has been borrowed from theism. The belief that the human species is a moral agent struggling to realise its inherent possibilities – the narrative of redemption that sustains secular humanists everywhere – is a hollowed-out version of a theistic myth. The idea that the human species is striving to achieve any purpose or goal – a universal state of freedom or justice, say – presupposes a pre-Darwinian, teleological way of thinking that has no place in science. Empirically speaking, there is no such collective human agent, only different human beings with conflicting goals and values. If you think of morality in scientific terms, as part of the behaviour of the human animal, you find that humans don’t live according to iterations of a single universal code. Instead, they have fashioned many ways of life. A plurality of moralities is as natural for the human animal as the variety of languages.

At this point, the dread spectre of relativism tends to be raised. Doesn’t talk of plural moralities mean there can be no truth in ethics? Well, anyone who wants their values secured by something beyond the capricious human world had better join an old-fashioned religion. If you set aside any view of humankind that is borrowed from monotheism, you have to deal with human beings as you find them, with their perpetually warring values.

This isn’t the relativism celebrated by postmodernists, which holds that human values are merely cultural constructions. Humans are like other animals in having a definite nature, which shapes their experiences whether they like it or not. No one benefits from being tortured or persecuted on account of their religion or sexuality. Being chronically poor is rarely, if ever, a positive experience. Being at risk of violent death is bad for human beings whatever their culture. Such truisms could be multiplied. Universal human values can be understood as something like moral facts, marking out goods and evils that are generically human. Using these universal values, it may be possible to define a minimum standard of civilised life that every society should meet; but this minimum won’t be the liberal values of the present time turned into universal principles.

Universal values don’t add up to a universal morality. Such values are very often conflicting, and different societies resolve these conflicts in divergent ways. The Ottoman empire, during some of its history, was a haven of toleration for religious communities who were persecuted in Europe; but this pluralism did not extend to enabling individuals to move from one community to another, or to form new communities of choice, as would be required by a liberal ideal of personal autonomy. The Hapsburg empire was based on rejecting the liberal principle of national self-determination; but – possibly for that very reason – it was more protective of minorities than most of the states that succeeded it. Protecting universal values without honouring what are now seen as core liberal ideals, these archaic imperial regimes were more civilised than a great many states that exist today.

For many, regimes of this kind are imperfect examples of what all human beings secretly want – a world in which no one is unfree. The conviction that tyranny and persecution are aberrations in human affairs is at the heart of the liberal philosophy that prevails today. But this conviction is supported by faith more than evidence. Throughout history there have been large numbers who have been happy to relinquish their freedom as long as those they hate – gay people, Jews, immigrants and other minorities, for example – are deprived of freedom as well. Many have been ready to support tyranny and oppression. Billions of human beings have been hostile to liberal values, and there is no reason for thinking matters will be any different in future.

An older generation of liberal thinkers accepted this fact. As the late Stuart Hampshire put it:

“It is not only possible, but, on present evidence, probable that most conceptions of the good, and most ways of life, which are typical of commercial, liberal, industrialised societies will often seem altogether hateful to substantial minorities within these societies and even more hateful to most of the populations within traditional societies … As a liberal by philosophical conviction, I think I ought to expect to be hated, and to be found superficial and contemptible, by a large part of mankind.”

Today this a forbidden thought. How could all of humankind not want to be as we imagine ourselves to be? To suggest that large numbers hate and despise values such as toleration and personal autonomy is, for many people nowadays, an intolerable slur on the species. This is, in fact, the quintessential illusion of the ruling liberalism: the belief that all human beings are born freedom-loving and peaceful and become anything else only as a result of oppressive conditioning. But there is no hidden liberal struggling to escape from within the killers of the Islamic State and Boko Haram, any more than there was in the torturers who served the Pol Pot regime. To be sure, these are extreme cases. But in the larger sweep of history, faith-based violence and persecution, secular and religious, are hardly uncommon – and they have been widely supported. It is peaceful coexistence and the practice of toleration that are exceptional.

* * *

Considering the alternatives that are on offer, liberal societies are well worth defending. But there is no reason for thinking these societies are the beginning of a species-wide secular civilisation of the kind of which evangelical atheists dream.

In ancient Greece and Rome, religion was not separate from the rest of human activity. Christianity was less tolerant than these pagan societies, but without it the secular societies of modern times would hardly have been possible. By adopting the distinction between what is owed to Caesar and what to God, Paul and Augustine – who turned the teaching of Jesus into a universal creed – opened the way for societies in which religion was no longer coextensive with life. Secular regimes come in many shapes, some liberal, others tyrannical. Some aim for a separation of church and state as in the US and France, while others – such as the Ataturkist regime that until recently ruled in Turkey – assert state control over religion. Whatever its form, a secular state is no guarantee of a secular culture. Britain has an established church, but despite that fact – or more likely because of it – religion has a smaller role in politics than in America and is less publicly divisive than it is in France.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Illustration by Christoph Hitz

There is no sign anywhere of religion fading away, but by no means all atheists have thought the disappearance of religion possible or desirable. Some of the most prominent – including the early 19th-century poet and philosopherGiacomo Leopardi, the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, the Austro-Hungarian philosopher and novelist Fritz Mauthner (who published a four-volume history of atheism in the early 1920s) and Sigmund Freud, to name a few – were all atheists who accepted the human value of religion. One thing these atheists had in common was a refreshing indifference to questions of belief. Mauthner – who is remembered today chiefly because of a dismissive one-line mention in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus – suggested that belief and unbelief were both expressions of a superstitious faith in language. For him, “humanity” was an apparition which melts away along with the departing Deity. Atheism was an experiment in living without taking human concepts as realities. Intriguingly, Mauthner saw parallels between this radical atheism and the tradition of negative theology in which nothing can be affirmed of God, and described the heretical medieval Christian mystic Meister Eckhart as being an atheist in this sense.

Above all, these unevangelical atheists accepted that religion is definitively human. Though not all human beings may attach great importance to them, every society contains practices that are recognisably religious. Why should religion be universal in this way? For atheist missionaries this is a decidedly awkward question. Invariably they claim to be followers of Darwin. Yet they never ask what evolutionary function this species-wide phenomenon serves. There is an irresolvable contradiction between viewing religion naturalistically – as a human adaptation to living in the world – and condemning it as a tissue of error and illusion. What if the upshot of scientific inquiry is that a need for illusion is built into in the human mind? If religions are natural for humans and give value to their lives, why spend your life trying to persuade others to give them up?

The answer that will be given is that religion is implicated in many human evils. Of course this is true. Among other things, Christianity brought with it a type of sexual repression unknown in pagan times. Other religions have their own distinctive flaws. But the fault is not with religion, any more than science is to blame for the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction or medicine and psychology for the refinement of techniques of torture. The fault is in the intractable human animal. Like religion at its worst, contemporary atheism feeds the fantasy that human life can be remade by a conversion experience – in this case, conversion to unbelief.

Evangelical atheists at the present time are missionaries for their own values. If an earlier generation promoted the racial prejudices of their time as scientific truths, ours aims to give the illusions of contemporary liberalism a similar basis in science. It’s possible to envision different varieties of atheism developing – atheisms more like those of Freud, which didn’t replace God with a flattering image of humanity. But atheisms of this kind are unlikely to be popular. More than anything else, our unbelievers seek relief from the panic that grips them when they realise their values are rejected by much of humankind. What today’s freethinkers want is freedom from doubt, and the prevailing version of atheism is well suited to give it to them.

In 1929, the Thinker’s Library, a series established by the Rationalist Press Association to advance secular thinking and counter the influence of religion in Britain, published an English translation of the German biologist Ernst Haeckel’s 1899 book The Riddle of the Universe. Celebrated as “the German Darwin”, Haeckel was one of the most influential public intellectuals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century; The Riddle of the Universe sold half a million copies in Germany alone, and was translated into dozens of other languages. Hostile to Jewish and Christian traditions, Haeckel devised his own “religion of science” called Monism, which incorporated an anthropology that divided the human species into a hierarchy of racial groups. Though he died in 1919, before the Nazi Party had been founded, his ideas, and widespread influence in Germany, unquestionably helped to create an intellectual climate in which policies of racial slavery and genocide were able to claim a basis in science.

The Thinker’s Library also featured works by Julian Huxley, grandson of TH Huxley, the Victorian biologist who was known as “Darwin’s bulldog” for his fierce defence of evolutionary theory. A proponent of “evolutionary humanism”, which he described as “religion without revelation”, Julian Huxley shared some of Haeckel’s views, including advocacy of eugenics. In 1931, Huxley wrote that there was “a certain amount of evidence that the negro is an earlier product of human evolution than the Mongolian or the European, and as such might be expected to have advanced less, both in body and mind”. Statements of this kind were then commonplace: there were many in the secular intelligentsia – including HG Wells, also a contributor to the Thinker’s Library – who looked forward to a time when “backward” peoples would be remade in a western mould or else vanish from the world.

But by the late 1930s, these views were becoming suspect: already in 1935, Huxley admitted that the concept of race was “hardly definable in scientific terms”. While he never renounced eugenics, little was heard from him on the subject after the second world war. The science that pronounced western people superior was bogus – but what shifted Huxley’s views wasn’t any scientific revelation: it was the rise of Nazism, which revealed what had been done under the aegis of Haeckel-style racism.

It has often been observed that Christianity follows changing moral fashions, all the while believing that it stands apart from the world. The same might be said, with more justice, of the prevalent version of atheism. If an earlier generation of unbelievers shared the racial prejudices of their time and elevated them to the status of scientific truths, evangelical atheists do the same with the liberal values to which western societies subscribe today – while looking with contempt upon “backward” cultures that have not abandoned religion. The racial theories promoted by atheists in the past have been consigned to the memory hole – and today’s most influential atheists would no more endorse racist biology than they would be seen following the guidance of an astrologer. But they have not renounced the conviction that human values must be based in science; now it is liberal values which receive that accolade. There are disputes, sometimes bitter, over how to define and interpret those values, but their supremacy is hardly ever questioned. For 21st century atheist missionaries, being liberal and scientific in outlook are one and the same.

It’s a reassuringly simple equation. In fact there are no reliable connections – whether in logic or history – between atheism, science and liberal values. When organised as a movement and backed by the power of the state, atheist ideologies have been an integral part of despotic regimes that also claimed to be based in science, such as the former Soviet Union. Many rival moralities and political systems – most of them, to date, illiberal – have attempted to assert a basis in science. All have been fraudulent and ephemeral. Yet the attempt continues in atheist movements today, which claim that liberal values can be scientifically validated and are therefore humanly universal.

Fortunately, this type of atheism isn’t the only one that has ever existed. There have been many modern atheisms, some of them more cogent and more intellectually liberating than the type that makes so much noise today. Campaigning atheism is a missionary enterprise, aiming to convert humankind to a particular version of unbelief; but not all atheists have been interested in propagating a new gospel, and some have been friendly to traditional faiths.

Evangelical atheists today view liberal values as part of an emerging global civilisation; but not all atheists, even when they have been committed liberals, have shared this comforting conviction. Atheism comes in many irreducibly different forms, among which the variety being promoted at the present time looks strikingly banal and parochial.

In itself, atheism is an entirely negative position. In pagan Rome, “atheist” (from the Greek atheos) meant anyone who refused to worship the established pantheon of deities. The term was applied to Christians, who not only refused to worship the gods of the pantheon but demanded exclusive worship of their own god. Many non-western religions contain no conception of a creator-god – Buddhism and Taoism, in some of their forms, are atheist religions of this kind – and many religions have had no interest in proselytising. In modern western contexts, however, atheism and rejection of monotheism are practically interchangeable. Roughly speaking, an atheist is anyone who has no use for the concept of God – the idea of a divine mind, which has created humankind and embodies in a perfect form the values that human beings cherish and strive to realise. Many who are atheists in this sense (including myself) regard the evangelical atheism that has emerged over the past few decades with bemusement. Why make a fuss over an idea that has no sense for you? There are untold multitudes who have no interest in waging war on beliefs that mean nothing to them. Throughout history, many have been happy to live their lives without bothering about ultimate questions. This sort of atheism is one of the perennial responses to the experience of being human.

As an organised movement, atheism is never non-committal in this way. It always goes with an alternative belief-system – typically, a set of ideas that serves to show the modern west is the high point of human development. In Europe from the late 19th century until the second world war, this was a version of evolutionary theory that marked out western peoples as being the most highly evolved. Around the time Haeckel was promoting his racial theories, a different theory of western superiority was developed by Marx. While condemning liberal societies and prophesying their doom, Marx viewed them as the high point of human development to date. (This is why he praised British colonialism in India as an essentially progressive development.) If Marx had serious reservations about Darwinism – and he did – it was because Darwin’s theory did not frame evolution as a progressive process.

The predominant varieties of atheist thinking, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, aimed to show that the secular west is the model for a universal civilisation. The missionary atheism of the present time is a replay of this theme; but the west is in retreat today, and beneath the fervour with which this atheism assaults religion there is an unmistakable mood of fear and anxiety. To a significant extent, the new atheism is the expression of a liberal moral panic.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Illustration by Christoph Hitz

Sam Harris, the American neuroscientist and author of The End of Faith: Religion, Terror and the Future of Reason (2004) and The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Moral Values (2010), who was arguably the first of the “new atheists”, illustrates this point. Following many earlier atheist ideologues, he wants a “scientific morality”; but whereas earlier exponents of this sort of atheism used science to prop up values everyone would now agree were illiberal, Harris takes for granted that what he calls a “science of good and evil” cannot be other than liberal in content. (Not everyone will agree with Harris’s account of liberal values, which appears to sanction the practice of torture: “Given what many believe are the exigencies of our war on terrorism,” he wrote in 2004, “the practice of torture, in certain circumstances, would seem to be not only permissible but necessary.”)