'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label prayer. Show all posts

Showing posts with label prayer. Show all posts

Saturday, 20 January 2024

Monday, 5 December 2022

Does religious faith lead to a happier, healthier life?

David Robson in The Guardian

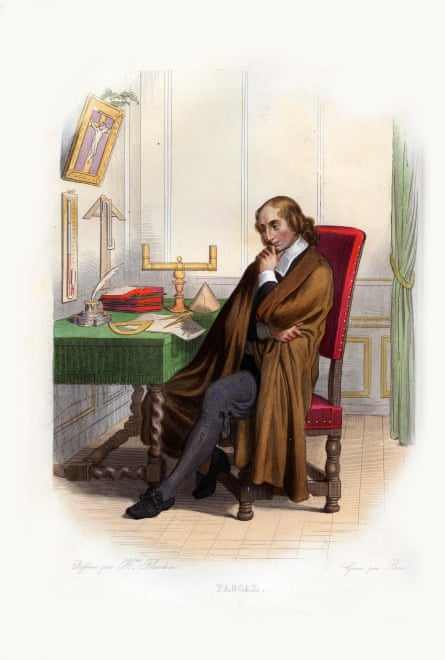

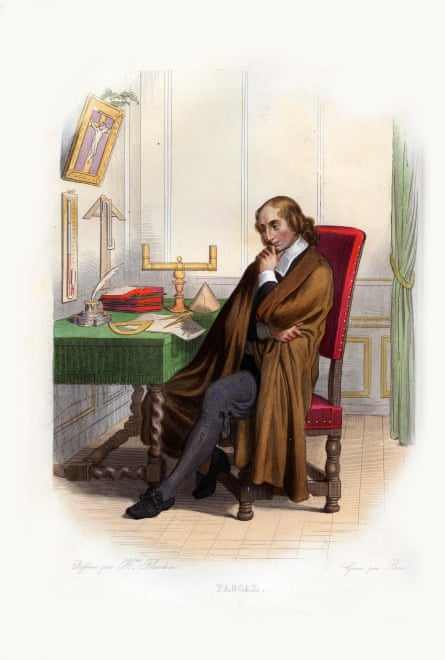

In his Pensées, published posthumously in 1670, the French philosopher Blaise Pascal appeared to establish a foolproof argument for religious commitment, which he saw as a kind of bet. If the existence of God was even minutely possible, he claimed, then the potential gain was so huge – an “eternity of life and happiness” – that taking the leap of faith was the mathematically rational choice.

Pascal’s wager implicitly assumes that religion has no benefits in the real world, but some sacrifices. But what if there were evidence that faith could also contribute to better wellbeing? Scientific studies suggest this is the case. Joining a church, synagogue or temple even appears to extend your lifespan.

These findings might appear to be proof of divine intervention, but few of the scientists examining these effects are making claims for miracles. Instead, they are interested in understanding the ways that it improves people’s capacity to deal with life’s stresses. “Religious and spiritual traditions give you access to different methods of coping that have distinctive benefits,” says Doug Oman, a professor in public health at the University of California Berkeley. “From the psychological perspective, religions offer a package of different ingredients,” agrees Prof Patty Van Cappellen at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

Studying the life-extending benefits of religious practice can therefore offer useful strategies for anyone – of any faith or none – to live a healthier and happier life. You may find yourself shaking your head in scepticism, but the evidence base linking faith to better health has been decades in the making and now encompasses thousands of studies. Much of this research took the form of longitudinal research, which involves tracking the health of a population over years and even decades. They each found that measures of someone’s religious commitment, such as how often they attended church, were consistently associated with a range of outcomes, including a lower risk of depression, anxiety and suicide and reduced cardiovascular disease and death from cancer.

In his Pensées, published posthumously in 1670, the French philosopher Blaise Pascal appeared to establish a foolproof argument for religious commitment, which he saw as a kind of bet. If the existence of God was even minutely possible, he claimed, then the potential gain was so huge – an “eternity of life and happiness” – that taking the leap of faith was the mathematically rational choice.

Pascal’s wager implicitly assumes that religion has no benefits in the real world, but some sacrifices. But what if there were evidence that faith could also contribute to better wellbeing? Scientific studies suggest this is the case. Joining a church, synagogue or temple even appears to extend your lifespan.

These findings might appear to be proof of divine intervention, but few of the scientists examining these effects are making claims for miracles. Instead, they are interested in understanding the ways that it improves people’s capacity to deal with life’s stresses. “Religious and spiritual traditions give you access to different methods of coping that have distinctive benefits,” says Doug Oman, a professor in public health at the University of California Berkeley. “From the psychological perspective, religions offer a package of different ingredients,” agrees Prof Patty Van Cappellen at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

Studying the life-extending benefits of religious practice can therefore offer useful strategies for anyone – of any faith or none – to live a healthier and happier life. You may find yourself shaking your head in scepticism, but the evidence base linking faith to better health has been decades in the making and now encompasses thousands of studies. Much of this research took the form of longitudinal research, which involves tracking the health of a population over years and even decades. They each found that measures of someone’s religious commitment, such as how often they attended church, were consistently associated with a range of outcomes, including a lower risk of depression, anxiety and suicide and reduced cardiovascular disease and death from cancer.

People who pray tend to have a more positive outlook on life – and those who pray for the wellbeing of others tend to live longer. Photograph: Kumar Sriskandan/Alamy

Unlike some other areas of scientific research suffering from the infamous “replication crisis”, these studies have examined populations across the globe, with remarkably consistent results. And the effect sizes are large. Dr Laura Wallace at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, for instance, recently examined obituaries of more than 1,000 people across the US and looked at whether the article recorded the person’s religious affiliation – a sign that their faith had been a major element of their identity.

Publishing her results in 2018, she reported that those people marked out for their faith lived for 5.6 years more, on average, than those whose religion had not been recorded; in a second sample, looking specifically at a set of obituaries from Des Moines in Iowa, the difference was even greater – about 10 years in total. “It’s on par with the avoidance of major health risks – like smoking,” says Wallace. To give another comparison: reducing hypertension adds about five years to someone’s life expectancy.

Health effects of this size demand explanation and scientists such as Wallace have been on the case. One obvious explanation for these findings is that people of faith live cleaner lives than the non-religious: studies show that churchgoers are indeed less likely to smoke, drink, take drugs or practise unsafe sex than people who do not attend a service regularly (though there are, of course, notable exceptions).

This healthier living may be the result of the religious teaching itself, which tends to encourage the principles of moderation and abstinence. But it could also be the fact that religious congregations are a self-selecting group. If you have sufficient willpower to get out of bed on a Sunday morning, for example, you may also have enough self-control to resist life’s other temptations.

Importantly, however, the health benefits of religion remain even when the scientists have controlled for these differences in behaviour, meaning that other factors must also contribute. Social connection comes top of the list. Feelings of isolation and loneliness are a serious source of stress in themselves and exacerbate the other challenges we face in life. Even something as simple as getting to work becomes far more difficult if you cannot call on a friend to give you a lift when your car breaks down.

Chronic stress response can result in physiological changes such as heightened inflammation, which, over the years, can damage tissue and increase your risk of illness. As a result, the size of someone’s social network and their subjective sense of connection with others can both predict their health and longevity, with one influential study by Prof Julianna Holt-Lunstad at Brigham Young University suggesting that the influence of loneliness is comparable to that of obesity or low physical exercise.

Unlike some other areas of scientific research suffering from the infamous “replication crisis”, these studies have examined populations across the globe, with remarkably consistent results. And the effect sizes are large. Dr Laura Wallace at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, for instance, recently examined obituaries of more than 1,000 people across the US and looked at whether the article recorded the person’s religious affiliation – a sign that their faith had been a major element of their identity.

Publishing her results in 2018, she reported that those people marked out for their faith lived for 5.6 years more, on average, than those whose religion had not been recorded; in a second sample, looking specifically at a set of obituaries from Des Moines in Iowa, the difference was even greater – about 10 years in total. “It’s on par with the avoidance of major health risks – like smoking,” says Wallace. To give another comparison: reducing hypertension adds about five years to someone’s life expectancy.

Health effects of this size demand explanation and scientists such as Wallace have been on the case. One obvious explanation for these findings is that people of faith live cleaner lives than the non-religious: studies show that churchgoers are indeed less likely to smoke, drink, take drugs or practise unsafe sex than people who do not attend a service regularly (though there are, of course, notable exceptions).

This healthier living may be the result of the religious teaching itself, which tends to encourage the principles of moderation and abstinence. But it could also be the fact that religious congregations are a self-selecting group. If you have sufficient willpower to get out of bed on a Sunday morning, for example, you may also have enough self-control to resist life’s other temptations.

Importantly, however, the health benefits of religion remain even when the scientists have controlled for these differences in behaviour, meaning that other factors must also contribute. Social connection comes top of the list. Feelings of isolation and loneliness are a serious source of stress in themselves and exacerbate the other challenges we face in life. Even something as simple as getting to work becomes far more difficult if you cannot call on a friend to give you a lift when your car breaks down.

Chronic stress response can result in physiological changes such as heightened inflammation, which, over the years, can damage tissue and increase your risk of illness. As a result, the size of someone’s social network and their subjective sense of connection with others can both predict their health and longevity, with one influential study by Prof Julianna Holt-Lunstad at Brigham Young University suggesting that the influence of loneliness is comparable to that of obesity or low physical exercise.

The 17th-century mathematician Blaise Pascal, author of the Pensées – and the famous wager. Photograph: Alamy

Religions, of course, tend to be built around a community of like-minded worshippers who meet regularly and have a shared set of beliefs. And many of the specific rituals will also contribute to a sense of communion with others. Christians, for example, are encouraged to pray on behalf of other people and this seems to bring its own health benefits, according to a brand new study by Prof Gail Ironson at the University of Miami.

Ironson has spent decades studying the ways that people with HIV cope with their infection and the influences of these psychological factors on the outcomes of disease. Examining data covering 17 years of 102 HIV patients’ lives, she found that people who regularly prayed for others were twice as likely to survive to the end of the study, compared with those who more regularly prayed for themselves. Importantly, the link remained even after Ironson had accounted for factors such as adherence to medications or substance abuse or the patient’s initial viral load.

Besides encouraging social connection, religion can help people to cultivate positive emotions that are good for our mental and physical wellbeing, such as gratitude and awe. Various studies show that regularly counting your blessings can help you to shift your focus away from the problems you are facing, preventing you from descending into the negative spirals of thinking that amplify stress. In the Christian church, you may be encouraged to thank God in your prayers, which encourages the cultivation of this protective emotion. “It’s a form of cognitive reappraisal,” says Van Cappellen. “It’s helping you to re-evaluate your situation in a more positive light.”

Awe, meanwhile, is the wonder we feel when we contemplate something much bigger and more important than ourselves. This can help people to cut through self-critical, ruminative thinking and to look beyond their daily concerns, so that they no longer make such a dent on your wellbeing.

Last, but not least, religious faiths can create a sense of purpose in someone’s life – the feeling that there is a reason and meaning to their existence. People with a sense of purpose tend to have better mental wellbeing, compared with those who feel that their lives lack direction, and – once again – this seems to have knock-on effects for physical health, including reduced mortality. “When people have a core set of values, it helps establish goals. And when those goals are established and pursued, that produces better psychological wellbeing,” says Prof Eric Kim at the University of British Columbia, who has researched the health benefits of purpose in life. Much like awe and gratitude, those positive feelings can then act as a buffer to stress.

Religions, of course, tend to be built around a community of like-minded worshippers who meet regularly and have a shared set of beliefs. And many of the specific rituals will also contribute to a sense of communion with others. Christians, for example, are encouraged to pray on behalf of other people and this seems to bring its own health benefits, according to a brand new study by Prof Gail Ironson at the University of Miami.

Ironson has spent decades studying the ways that people with HIV cope with their infection and the influences of these psychological factors on the outcomes of disease. Examining data covering 17 years of 102 HIV patients’ lives, she found that people who regularly prayed for others were twice as likely to survive to the end of the study, compared with those who more regularly prayed for themselves. Importantly, the link remained even after Ironson had accounted for factors such as adherence to medications or substance abuse or the patient’s initial viral load.

Besides encouraging social connection, religion can help people to cultivate positive emotions that are good for our mental and physical wellbeing, such as gratitude and awe. Various studies show that regularly counting your blessings can help you to shift your focus away from the problems you are facing, preventing you from descending into the negative spirals of thinking that amplify stress. In the Christian church, you may be encouraged to thank God in your prayers, which encourages the cultivation of this protective emotion. “It’s a form of cognitive reappraisal,” says Van Cappellen. “It’s helping you to re-evaluate your situation in a more positive light.”

Awe, meanwhile, is the wonder we feel when we contemplate something much bigger and more important than ourselves. This can help people to cut through self-critical, ruminative thinking and to look beyond their daily concerns, so that they no longer make such a dent on your wellbeing.

Last, but not least, religious faiths can create a sense of purpose in someone’s life – the feeling that there is a reason and meaning to their existence. People with a sense of purpose tend to have better mental wellbeing, compared with those who feel that their lives lack direction, and – once again – this seems to have knock-on effects for physical health, including reduced mortality. “When people have a core set of values, it helps establish goals. And when those goals are established and pursued, that produces better psychological wellbeing,” says Prof Eric Kim at the University of British Columbia, who has researched the health benefits of purpose in life. Much like awe and gratitude, those positive feelings can then act as a buffer to stress.

Volunteers sort produce at a food bank warehouse in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, in February this year. People who spend time helping others seem to live longer. Photograph: Vickie Flores/EPA

These are average effects, which don’t always take into account that huge variety of people’s experiences. While some Christians might see God as a benevolent figure, others might have been taught that he is judgmental and punishing and those views can make a big difference in the effects on our health. In her studies of HIV patients, Ironson found that people who believed in a vengeful God showed a faster disease progression – as measured by their declining white blood cell count – compared with those who believed that he was a merciful figure.

Ultimately, most people’s faith will arise from real convictions; it seems unlikely that many people would adopt a particular religious view solely for the health benefits. But even if you are agnostic, like me, or atheist, this research might inform your lifestyle.

You can start by considering contemplative techniques, which come in many more forms than the mindful breathing and body-scan techniques that have proved so popular. Scientists have become increasingly interested in “loving-kindness meditation”, for example, in which you spend a few moments thinking warm thoughts about friends, strangers, even enemies. The practice was inspired by the Buddhist principle of mettā, but it also resembles the Christian practice of intercessory prayer. When practised regularly, this increases people’s feelings of social connection and empathy with the consequent benefits for their mental health. Importantly, it also changes people’s real-life actions towards others, for instance encouraging more pro-social behaviour.

The power of religion is that it gives you this package of ingredients that are pre-made and organised for youProf Patty Van Cappellen

To build more gratitude into your life, meanwhile, you might keep a diary listing the things that you have appreciated each day and you can make a deliberate habit of thanking the people who have helped you; both strategies have been shown to improve people’s stress responses and to improve overall wellbeing. And to cultivate awe, you might go on a regular nature walk, visit a magnificent building within your city or watch a film that fills you with wonder.

If you have time and resources for greater commitments, you could also take up a voluntary activity for a cause that means a lot to you, a task that may help to boost your sense of purpose and which could also enhance your social life. Dr Wallace’s work has shown that the sheer amount of volunteering someone performs could, independently, explain part of the longevity boost of religious people, but charitable actions do not need to be linked to a particular faith for you to gain those benefits. “If people are able to plug into causes that really light up their intrinsic values, and then find a community that helps them reach their goals, that’s another way in which the framework of religion can be taken into a non-religious context,” says Prof Kim.

The challenge is to ensure that you build all these behaviours into your routine, so that you perform them with the same regularity and devotion normally reserved for spiritual practices. “The power of religion is that it gives you this package of ingredients that are pre-made and organised for you,” says Van Cappellen. “And if you are not religious you have to create it on your own.” You don’t need to make a leap of faith to see those benefits.

These are average effects, which don’t always take into account that huge variety of people’s experiences. While some Christians might see God as a benevolent figure, others might have been taught that he is judgmental and punishing and those views can make a big difference in the effects on our health. In her studies of HIV patients, Ironson found that people who believed in a vengeful God showed a faster disease progression – as measured by their declining white blood cell count – compared with those who believed that he was a merciful figure.

Ultimately, most people’s faith will arise from real convictions; it seems unlikely that many people would adopt a particular religious view solely for the health benefits. But even if you are agnostic, like me, or atheist, this research might inform your lifestyle.

You can start by considering contemplative techniques, which come in many more forms than the mindful breathing and body-scan techniques that have proved so popular. Scientists have become increasingly interested in “loving-kindness meditation”, for example, in which you spend a few moments thinking warm thoughts about friends, strangers, even enemies. The practice was inspired by the Buddhist principle of mettā, but it also resembles the Christian practice of intercessory prayer. When practised regularly, this increases people’s feelings of social connection and empathy with the consequent benefits for their mental health. Importantly, it also changes people’s real-life actions towards others, for instance encouraging more pro-social behaviour.

The power of religion is that it gives you this package of ingredients that are pre-made and organised for youProf Patty Van Cappellen

To build more gratitude into your life, meanwhile, you might keep a diary listing the things that you have appreciated each day and you can make a deliberate habit of thanking the people who have helped you; both strategies have been shown to improve people’s stress responses and to improve overall wellbeing. And to cultivate awe, you might go on a regular nature walk, visit a magnificent building within your city or watch a film that fills you with wonder.

If you have time and resources for greater commitments, you could also take up a voluntary activity for a cause that means a lot to you, a task that may help to boost your sense of purpose and which could also enhance your social life. Dr Wallace’s work has shown that the sheer amount of volunteering someone performs could, independently, explain part of the longevity boost of religious people, but charitable actions do not need to be linked to a particular faith for you to gain those benefits. “If people are able to plug into causes that really light up their intrinsic values, and then find a community that helps them reach their goals, that’s another way in which the framework of religion can be taken into a non-religious context,” says Prof Kim.

The challenge is to ensure that you build all these behaviours into your routine, so that you perform them with the same regularity and devotion normally reserved for spiritual practices. “The power of religion is that it gives you this package of ingredients that are pre-made and organised for you,” says Van Cappellen. “And if you are not religious you have to create it on your own.” You don’t need to make a leap of faith to see those benefits.

Monday, 6 June 2022

Sunday, 2 January 2022

Thursday, 3 July 2014

Rowan Williams: how Buddhism helps me pray

John Bingham in The Telegraph

The former Archbishop of Canterbury Lord Williams has disclosed that he spends up to 40 minutes a day squatting and repeating an Eastern Orthodox prayer while performing breathing exercises as part of a routine influenced by Buddhism.

He also spends time pacing slowly and repeatedly prostrating himself as part of an intense early morning ritual of silent meditation and prayer.

The normally private former Archbishop has given a glimpse of his personal devotions in an article for the New Statesman explaining the power of religious ritual in an increasingly secular world.

Lord Williams has spoken in the past about how in his youth he contemplated becoming a monk as well as joining the Orthodox church.

He explained that he draws daily inspiration from the practice, common to both the Greek and Russian orthodox churches, of meditating while repeatedly reciting the “Jesus Prayer”, which says: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy upon me, a sinner”.

“Over the years increasing exposure to and engagement with the Buddhist world in particular has made me aware of practices not unlike the ‘Jesus Prayer’ and introduced me to disciplines that further enforce the stillness and physical focus that the prayer entails,” he explained

“Walking meditation, pacing very slowly and coordinating each step with an out-breath, is something I have found increasingly important as a preparation for a longer time of silence.

“So: the regular ritual to begin the day when I’m in the house is a matter of an early rise and a brief walking meditation or sometimes a few slow prostrations, before squatting for 30 or 40 minutes (a low stool to support the thighs and reduce the weight on the lower legs) with the 'Jesus Prayer': repeating (usually silently) the words as I breathe out, leaving a moment between repetitions to notice the beating of the heart, which will slow down steadily over the period.”

Far from it being like a “magical invocation”, he explained that the routine helps him detach himself from “distracted, wandering images and thoughts”, picturing the human body as like a 'cave' through which breath passes.

“If you want to speak theologically about it, it’s a time when you are aware of your body as simply a place where life happens and where, therefore, God ‘happens’: a life lived in you,” he added.

He went on to explain that those who perform such rituals regularly could reach "advanced states" and become aware of an "unbroken inner light".

Monday, 27 May 2013

To be right on intellectual matters is of limited importance and interest to the outside world.

I'm an atheist but … I won't try to deconvert anyone

New atheism won't tolerate the freedom to believe in God. But life's far more interesting if we admit we might be wrong, right?

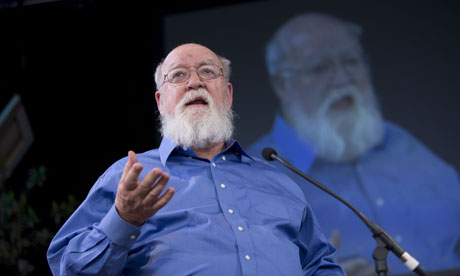

Philosopher and 'new atheist' Daniel Dennett speaking at the Hay Festival. Photograph: David Levenson/Getty Images

Last week I interviewed the philosopher Daniel Dennett about new atheism, (the interview will be up on this site soon). I haven't got the tape myself, so I can't swear to the verbatim accuracy of the quotes I remember, but at one stage I said something to the effect that new atheism seems to me to reproduce all the habits that made religion obnoxious, like heresy hunting. He asked what I meant, and I gave the example of "atheists but", a species of which he is particularly disdainful. They are the people who will say to him and his fellow zealots "I am an atheist, but I don't go along with your campaign." I'm one of them.

He accused me of a kind of intellectual snobbery – of believing that I am clever and brave and strong enough to understand that there is no God, but that this is a discovery too shattering for the common people who should be left in the comfort of their ignorance.

This was indeed the classic position of the anti-religious philosophers of the enlightenment. It is what Voltaire believed, and Gibbon, and Hume. So it's not as if you have to be an idiot to think that atheism is medicine too strong for most people. And when you see the relish with which some atheists dismiss their opponents as "morons" you might even suppose that even some atheists are attracted by the idea that they are of necessity cleverer than believers.

But that's not in fact my position at all. The reason that I don't go around trying to deconvert all my Christian friends is that they know the arguments against a belief in God so very much better than I do. I can entertain the possibility that Christianity is true. They have to take it seriously. I don't believe I ought to love my neighbour, however much patience and humility this takes. I know that prayers go unanswered: they know their own prayers do.

I am not the person who has to bury the tramps, to comfort the parents whose children have died, or to read the Bible in the hope that it will yield meaning. I don't even have to believe that the Holy Spirit works through the college of cardinals or General Synod, so that their deliberations are in some way connected with the redemption of the world.

Only the last of those duties is a mark of moral or intellectual weakness. In fact, since I like my friends to be admirable, which often means cleverer and nicer than I am, my Christian friends don't seem to me stupid or cowardly. I know lots of Christians who are both, of course. But that's true of atheists and Muslims as well.

There is a general point here about the inadequacy of all theological opinions. The "but" in "atheists but" is a mark of humility, to be worn with pride. To be right on intellectual matters is of limited importance and interest to the outside world. Assuming – rashly – that you are an intellectual, it is very much easier to be right about ideas than to work out their implications and act on them in real life. But that's the bit that matters more, if only because failure to act on your own beliefs involves lying to yourself, and this will over time corrupt the capacity for thought.

The "but" is a way of saying that the times when we are right are mostly less interesting than the times when we are wrong. They certainly demand our attention less. It's a way of saying that we might be wrong, and actually meaning it. It's a demand to try to listen to what the other person means, rather than dismiss what they say just because it makes no sense.

It is, in short, a rejection of all the values of online argument so it really can't be wrong. Discuss.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)