'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label atheist. Show all posts

Showing posts with label atheist. Show all posts

Thursday, 28 August 2025

Friday, 17 March 2023

Monday, 26 July 2021

Saturday, 28 September 2019

Tuesday, 27 February 2018

Overcoming superstition - Persuasion lessons for rationalists

Rahul Siddharthan in The Hindu

The Indian Constitution is unique in listing, among fundamental duties, the duty of each citizen “to develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform” (Article 51A). Jawaharlal Nehru was the first to use the expression “scientific temper”, which he described with his usual lucidity in The Discovery of India (while also quoting Blaise Pascal on the limits of reason). And yet, decades later, superstitious practices abound in India, including among the highly educated.

Superstition exists

India may be unusual in the degree and variety of superstitious practices, even among the educated, but superstition exists everywhere. In his recent Editorial page article, “Science should have the last word” (The Hindu, February 17), Professor Jayant V. Narlikar, cosmologist and a life-long advocate for rationality, cites Czech astronomer Jiří Grygar’s observation that though the Soviets suppressed superstitious ideas in then-Czechoslovakia during the occupation, superstition arose again in the “free-thinking”, post-Soviet days. Superstition never went away: people just hesitated to discuss it in public.

Similarly, China suppressed superstition and occult practices during Mao Zedong’s rule. But after the economic reforms and relative openness that began in the late 1970s, superstition reportedly made a comeback, with even top party officials consulting soothsayers on their fortunes. In India, the rationalist movements of Periyar and others have barely made a dent. No country, no matter its scientific prowess, has conquered superstition.

On the positive side, internationally, increasing numbers of people live happily without need for superstition. The most appalling beliefs and rituals have largely been eradicated the world over — such as blood-letting in medicine to human sacrifice, and in India, practices such as sati. This is due to the efforts put in by social reform campaigners, education and empowerment (of women in particular). Yet, surviving superstitions can be dangerous too, for example when they contradict medical advice.

Explaining it

Why is it so hard to remove superstitions? Fundamentally, a belief may be difficult to shake off simply because of deep-seated habituation. In his memoir Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, the physicist Richard P. Feynman wrote about being hypnotised voluntarily (hypnosis is always voluntary) on stage, doing what was asked, and thinking to himself that he was just agreeing to everything to not “disturb the situation”. Finally, the hypnotist announced that Feynman would not go straight back to his chair but would walk all around the room first. Feynman decided that this was ridiculous; he would walk straight back to his seat. “But then,” he said, “an annoying feeling came over me: I felt so uncomfortable that I couldn’t continue. I walked all the way around the hall.”

We have all had such “uncomfortable feelings” when trying to do something differently, even if it seems to be logically better: whether it’s a long-standing kitchen practice, or an entrenched approach to classroom teaching, or something else in daily life. Perhaps we are all hypnotised by our previous experiences, and superstition, in particular, is a form of deep-seated hypnosis that is very hard to undo. It is undone only when the harm is clear and evident, as in the medieval practices alluded to earlier. Such beliefs are strengthened by a confirmation bias (giving importance to facts that agree with our preconceptions and ignoring others) and other logical holes. Recent research even shows how seeing the same evidence can simultaneously strengthen oppositely-held beliefs (a phenomenon called Bayesian belief polarisation).

Disagreement in science

Dogmatism about science can be unjustified too. All scientific theories have limitations. Newton’s theories of mechanics and gravitation were superseded by Einstein’s. Einstein’s theory of gravity has no known limitations at the cosmological scale, but is incompatible with quantum mechanics. The evolution of species is an empirical fact: the fossil record attests it, and we can also observe it in action in fast-breeding species. Darwinism is a theory to explain how it occurs. Today’s version is a combination of Darwin’s original ideas, Mendelian genetics and population biology, with much empirical validation and no known failures. But it does have gaps. For example, epigenetic inheritance is not well understood and remains an active area of research. Incidentally, Dr. Narlikar in his article has suggested that Darwinism’s inability to explain the origin of life is a gap. Few evolutionary biologists would agree. Darwin’s book was after all titled The Origin of Species, and the origin of life would seem beyond its scope. But this is an example of how scientists can disagree on details while agreeing on the big picture.

How then does one eradicate superstition? Not, as the evidence suggests, by preaching or legislating against it. Awareness campaigns against dangerous superstitions along with better education and scientific outreach may have some impact but will be a slow process.

Today, the topic of “persuasion” is popular in the psychology, social science and marketing communities. Perhaps scientists have something to learn here too. Pascal, whom Nehru cited on reason, wrote on persuasion too. He observed that the first step is to see the matter from the other person’s point of view and acknowledge the validity of their perception, and then bring in its limitations. “People are generally better persuaded by the reasons which they have themselves discovered than by those which have come into the mind of others.”

Such a strategy may be more successful than the aggressive campaigns of rationalists such as Richard Dawkins. Nevertheless, “harmless” superstitions are likely to remain with humanity forever.

The Indian Constitution is unique in listing, among fundamental duties, the duty of each citizen “to develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform” (Article 51A). Jawaharlal Nehru was the first to use the expression “scientific temper”, which he described with his usual lucidity in The Discovery of India (while also quoting Blaise Pascal on the limits of reason). And yet, decades later, superstitious practices abound in India, including among the highly educated.

Superstition exists

India may be unusual in the degree and variety of superstitious practices, even among the educated, but superstition exists everywhere. In his recent Editorial page article, “Science should have the last word” (The Hindu, February 17), Professor Jayant V. Narlikar, cosmologist and a life-long advocate for rationality, cites Czech astronomer Jiří Grygar’s observation that though the Soviets suppressed superstitious ideas in then-Czechoslovakia during the occupation, superstition arose again in the “free-thinking”, post-Soviet days. Superstition never went away: people just hesitated to discuss it in public.

Similarly, China suppressed superstition and occult practices during Mao Zedong’s rule. But after the economic reforms and relative openness that began in the late 1970s, superstition reportedly made a comeback, with even top party officials consulting soothsayers on their fortunes. In India, the rationalist movements of Periyar and others have barely made a dent. No country, no matter its scientific prowess, has conquered superstition.

On the positive side, internationally, increasing numbers of people live happily without need for superstition. The most appalling beliefs and rituals have largely been eradicated the world over — such as blood-letting in medicine to human sacrifice, and in India, practices such as sati. This is due to the efforts put in by social reform campaigners, education and empowerment (of women in particular). Yet, surviving superstitions can be dangerous too, for example when they contradict medical advice.

Explaining it

Why is it so hard to remove superstitions? Fundamentally, a belief may be difficult to shake off simply because of deep-seated habituation. In his memoir Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, the physicist Richard P. Feynman wrote about being hypnotised voluntarily (hypnosis is always voluntary) on stage, doing what was asked, and thinking to himself that he was just agreeing to everything to not “disturb the situation”. Finally, the hypnotist announced that Feynman would not go straight back to his chair but would walk all around the room first. Feynman decided that this was ridiculous; he would walk straight back to his seat. “But then,” he said, “an annoying feeling came over me: I felt so uncomfortable that I couldn’t continue. I walked all the way around the hall.”

We have all had such “uncomfortable feelings” when trying to do something differently, even if it seems to be logically better: whether it’s a long-standing kitchen practice, or an entrenched approach to classroom teaching, or something else in daily life. Perhaps we are all hypnotised by our previous experiences, and superstition, in particular, is a form of deep-seated hypnosis that is very hard to undo. It is undone only when the harm is clear and evident, as in the medieval practices alluded to earlier. Such beliefs are strengthened by a confirmation bias (giving importance to facts that agree with our preconceptions and ignoring others) and other logical holes. Recent research even shows how seeing the same evidence can simultaneously strengthen oppositely-held beliefs (a phenomenon called Bayesian belief polarisation).

Disagreement in science

Dogmatism about science can be unjustified too. All scientific theories have limitations. Newton’s theories of mechanics and gravitation were superseded by Einstein’s. Einstein’s theory of gravity has no known limitations at the cosmological scale, but is incompatible with quantum mechanics. The evolution of species is an empirical fact: the fossil record attests it, and we can also observe it in action in fast-breeding species. Darwinism is a theory to explain how it occurs. Today’s version is a combination of Darwin’s original ideas, Mendelian genetics and population biology, with much empirical validation and no known failures. But it does have gaps. For example, epigenetic inheritance is not well understood and remains an active area of research. Incidentally, Dr. Narlikar in his article has suggested that Darwinism’s inability to explain the origin of life is a gap. Few evolutionary biologists would agree. Darwin’s book was after all titled The Origin of Species, and the origin of life would seem beyond its scope. But this is an example of how scientists can disagree on details while agreeing on the big picture.

How then does one eradicate superstition? Not, as the evidence suggests, by preaching or legislating against it. Awareness campaigns against dangerous superstitions along with better education and scientific outreach may have some impact but will be a slow process.

Today, the topic of “persuasion” is popular in the psychology, social science and marketing communities. Perhaps scientists have something to learn here too. Pascal, whom Nehru cited on reason, wrote on persuasion too. He observed that the first step is to see the matter from the other person’s point of view and acknowledge the validity of their perception, and then bring in its limitations. “People are generally better persuaded by the reasons which they have themselves discovered than by those which have come into the mind of others.”

Such a strategy may be more successful than the aggressive campaigns of rationalists such as Richard Dawkins. Nevertheless, “harmless” superstitions are likely to remain with humanity forever.

Saturday, 29 April 2017

Why they lynched Mashal Khan. Lessons for humans.

Pervez Hoodbhoy in The Dawn

THE mental state of men ready and poised to kill has long fascinated scientists. The Nobel Prize winning ethologist, Konrad Lorenz, says such persons experience the ‘Holy Shiver’ (called Heiliger Schauer in German) just moments before performing the deed. In his famous book On Aggression, Lorenz describes it as a tingling of the spine prior to performing a heroic act in defence of their communities.

This feeling, he says, is akin to the pre-human reflex that raises hair on an animal’s back as it zeroes in for the kill. He writes: “A shiver runs down the back and along the outside of both arms. All obstacles become unimportant … instinctive inhibitions against hurting or killing disappear … Men enjoy the feeling of absolute righteousness even as they commit atrocities.”

While they stripped naked and beat their colleague Mashal Khan with sticks and bricks, the 20-25 students of the Mardan university enjoyed precisely this feeling of righteousness. They said Khan had posted content disrespectful of Islam on his Facebook page and so they took it upon themselves to punish him. Finally, one student took out his pistol and shot him dead. Hundreds of others watched approvingly and, with their smartphone cameras, video-recorded the killing for distribution on their Facebook pages. A meeting of this self-congratulatory group resolved to hide the identity of the shooter.

Khan had blasphemed! Until this was finally shown to be false, no proper funeral was possible in his home village. Sympathy messages from Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and opposition leaders such as Bilawal Bhutto came only after it had been established that Khan performed namaz fairly regularly.

Significantly, no protests of significance followed. University campuses were silent and meetings discussing the murder were disallowed. A demonstration at the Islamabad Press Club drew about 450, a miniscule figure against the estimated 200,000 who attended Mumtaz Qadri’s last rites.

This suggests that much of the Pakistani public, whether tacitly or openly, endorses violent punishment of suspected blasphemers. Why? How did so many Pakistanis become bloodthirsty vigilantes? Evening TV talk shows — at least those I have either seen or participated in — circle around two basic explanations.

One, favoured by the liberal-minded, blames the blasphemy law and implicitly demands its repeal (an explicit call would endanger one’s life). The other, voiced by the religiously orthodox, says vigilantism occurs only because our courts act too slowly against accused blasphemers.

Both claims are not just wrong, they are farcical. Subsequent to Khan’s killing, at least two other incidents show that gut reactions — not what some law says — is really what counts. In one, three armed burqa-clad sisters shot dead a man near Sialkot who had been accused of committing blasphemy 13 years ago. In the other, a visibly mentally ill man in Chitral uttered remarks inside a mosque and escaped lynching only upon the imam’s intervention. The mob subsequently burned the imam’s car. Heiliger Schauer!

While searching for a real explanation, let’s first note that religiously charged mobs are also in motion across the border. As more people flock to mandirs or masjids, the outcomes are strikingly similar. In an India that is now rapidly Hinduising, crowds are cheering enraged gau rakshaks who smash the skulls of Muslims suspected of consuming or transporting cows. In fact India has its own Khan — Pehlu Khan.

Accused of cattle-smuggling, Pehlu Khan was lynched and killed by cow vigilantes earlier this month before a cheering crowd in Alwar, with the episode also video-recorded. Minister Gulab Chand Kataria declared that Khan belonged to a family of cow smugglers and he had no reason to feel sorry. Now that cow slaughter has been hyped as the most heinous of crimes, no law passed in India can reverse vigilantism.

Vigilantism is best explained by evolutionary biology and sociology. A fundamental principle there says only actions and thoughts that help strengthen group identity are well received, others are not. In common with our ape ancestors, we humans instinctively band together in groups because strength lies in unity. The benefits of group membership are immense — access to social networks, enhanced trust, recognition, etc. Of course, as in a club, membership carries a price tag. Punishing cow-eaters or blasphemers (even alleged ones will do) can be part payment. You become a real hero by slaying a villain — ie someone who challenges your group’s ethos. Your membership dues are also payable by defending or eulogising heroes.

Celebration of such ‘heroes’ precedes Qadri. The 19-year old illiterate who killed Raj Pal, the Hindu publisher of a controversial book on the Prophet (PBUH), was subsequently executed by the British but the youth was held in the highest esteem. Ghazi Ilm Din is venerated by a mausoleum over his grave in Lahore. An 8th grade KP textbook chapter eulogising him tells us that Ilm Din’s body remained fresh days after the execution.

In recent times, backed by the formidable power of the state, Hindu India and Islamic Pakistan have vigorously injected religion into both politics and society. The result is their rapid re-tribalisation through ‘meme transmission’ of primal values. A concept invented by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, the meme is a ‘piece of thought’ transferrable from person to person by imitation. Like computer viruses, memes can jump from mind to mind.

Memes containing notions of religious or cultural superiority have been ‘cut-and-pasted’ into millions of young minds. Consequently, more than ever before, today’s youth uncritically accepts the inherent morality of their particular group, engages in self-censorship, rationalises the group’s decisions, and engages in moral policing.

Groupthink and deadly memes caused the lynching and murder of the two Khans. Is a defence against such viral afflictions ever possible? Can the subcontinent move away from its barbaric present to a civilised future? One can so hope. After all, like fleas, memes and thought packages can jump from person to person. But they don’t bite everybody! A robust defence can be built by educating people into the spirit of critical inquiry, helping them become individuals rather than groupies, and encouraging them to introspect. A sense of humour, and maybe poetry, would also help.

THE mental state of men ready and poised to kill has long fascinated scientists. The Nobel Prize winning ethologist, Konrad Lorenz, says such persons experience the ‘Holy Shiver’ (called Heiliger Schauer in German) just moments before performing the deed. In his famous book On Aggression, Lorenz describes it as a tingling of the spine prior to performing a heroic act in defence of their communities.

This feeling, he says, is akin to the pre-human reflex that raises hair on an animal’s back as it zeroes in for the kill. He writes: “A shiver runs down the back and along the outside of both arms. All obstacles become unimportant … instinctive inhibitions against hurting or killing disappear … Men enjoy the feeling of absolute righteousness even as they commit atrocities.”

While they stripped naked and beat their colleague Mashal Khan with sticks and bricks, the 20-25 students of the Mardan university enjoyed precisely this feeling of righteousness. They said Khan had posted content disrespectful of Islam on his Facebook page and so they took it upon themselves to punish him. Finally, one student took out his pistol and shot him dead. Hundreds of others watched approvingly and, with their smartphone cameras, video-recorded the killing for distribution on their Facebook pages. A meeting of this self-congratulatory group resolved to hide the identity of the shooter.

Khan had blasphemed! Until this was finally shown to be false, no proper funeral was possible in his home village. Sympathy messages from Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and opposition leaders such as Bilawal Bhutto came only after it had been established that Khan performed namaz fairly regularly.

Significantly, no protests of significance followed. University campuses were silent and meetings discussing the murder were disallowed. A demonstration at the Islamabad Press Club drew about 450, a miniscule figure against the estimated 200,000 who attended Mumtaz Qadri’s last rites.

This suggests that much of the Pakistani public, whether tacitly or openly, endorses violent punishment of suspected blasphemers. Why? How did so many Pakistanis become bloodthirsty vigilantes? Evening TV talk shows — at least those I have either seen or participated in — circle around two basic explanations.

One, favoured by the liberal-minded, blames the blasphemy law and implicitly demands its repeal (an explicit call would endanger one’s life). The other, voiced by the religiously orthodox, says vigilantism occurs only because our courts act too slowly against accused blasphemers.

Both claims are not just wrong, they are farcical. Subsequent to Khan’s killing, at least two other incidents show that gut reactions — not what some law says — is really what counts. In one, three armed burqa-clad sisters shot dead a man near Sialkot who had been accused of committing blasphemy 13 years ago. In the other, a visibly mentally ill man in Chitral uttered remarks inside a mosque and escaped lynching only upon the imam’s intervention. The mob subsequently burned the imam’s car. Heiliger Schauer!

While searching for a real explanation, let’s first note that religiously charged mobs are also in motion across the border. As more people flock to mandirs or masjids, the outcomes are strikingly similar. In an India that is now rapidly Hinduising, crowds are cheering enraged gau rakshaks who smash the skulls of Muslims suspected of consuming or transporting cows. In fact India has its own Khan — Pehlu Khan.

Accused of cattle-smuggling, Pehlu Khan was lynched and killed by cow vigilantes earlier this month before a cheering crowd in Alwar, with the episode also video-recorded. Minister Gulab Chand Kataria declared that Khan belonged to a family of cow smugglers and he had no reason to feel sorry. Now that cow slaughter has been hyped as the most heinous of crimes, no law passed in India can reverse vigilantism.

Vigilantism is best explained by evolutionary biology and sociology. A fundamental principle there says only actions and thoughts that help strengthen group identity are well received, others are not. In common with our ape ancestors, we humans instinctively band together in groups because strength lies in unity. The benefits of group membership are immense — access to social networks, enhanced trust, recognition, etc. Of course, as in a club, membership carries a price tag. Punishing cow-eaters or blasphemers (even alleged ones will do) can be part payment. You become a real hero by slaying a villain — ie someone who challenges your group’s ethos. Your membership dues are also payable by defending or eulogising heroes.

Celebration of such ‘heroes’ precedes Qadri. The 19-year old illiterate who killed Raj Pal, the Hindu publisher of a controversial book on the Prophet (PBUH), was subsequently executed by the British but the youth was held in the highest esteem. Ghazi Ilm Din is venerated by a mausoleum over his grave in Lahore. An 8th grade KP textbook chapter eulogising him tells us that Ilm Din’s body remained fresh days after the execution.

In recent times, backed by the formidable power of the state, Hindu India and Islamic Pakistan have vigorously injected religion into both politics and society. The result is their rapid re-tribalisation through ‘meme transmission’ of primal values. A concept invented by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, the meme is a ‘piece of thought’ transferrable from person to person by imitation. Like computer viruses, memes can jump from mind to mind.

Memes containing notions of religious or cultural superiority have been ‘cut-and-pasted’ into millions of young minds. Consequently, more than ever before, today’s youth uncritically accepts the inherent morality of their particular group, engages in self-censorship, rationalises the group’s decisions, and engages in moral policing.

Groupthink and deadly memes caused the lynching and murder of the two Khans. Is a defence against such viral afflictions ever possible? Can the subcontinent move away from its barbaric present to a civilised future? One can so hope. After all, like fleas, memes and thought packages can jump from person to person. But they don’t bite everybody! A robust defence can be built by educating people into the spirit of critical inquiry, helping them become individuals rather than groupies, and encouraging them to introspect. A sense of humour, and maybe poetry, would also help.

Sunday, 22 January 2017

Wednesday, 17 June 2015

The Pope can see what many atheist greens will not

George Monbiot in The Guardian

Who wants to see the living world destroyed? Who wants an end to birdsong, bees and coral reefs, the falcon’s stoop, the salmon’s leap? Who wants to see the soil stripped from the land, the sea rimed with rubbish?

No one. And yet it happens. Seven billion of us allow fossil fuel companies to push shut the narrow atmospheric door through which humanity stepped. We permit industrial farming to tear away the soil, banish trees from the hills, engineer another silent spring. We let the owners of grouse moors, 1% of the 1%, shoot and poison hen harriers, peregrines and eagles. We watch mutely as a small fleet of monster fishing ships trashes the oceans.

Why are the defenders of the living world so ineffective? It is partly, of course, that everyone is complicit; we have all been swept off our feet by the tide of hyperconsumption, our natural greed excited, corporate propaganda chiming with a will to believe that there is no cost. But perhaps environmentalism is also afflicted by a deeper failure: arising possibly from embarrassment or fear, a failure of emotional honesty

.

FacebookTwitterPinterest ‘We have all been swept off our feet by the tide of hyperconsumption, our natural greed excited, corporate propaganda chiming with a will to believe that there is no cost’.

I have asked meetings of green-minded people to raise their hands if they became defenders of nature because they were worried about the state of their bank accounts. Never has one hand appeared. Yet I see the same people base their appeal to others on the argument that they will lose money if we don’t protect the natural world.

Such claims are factual, but they are also dishonest: we pretend that this is what animates us, when in most cases it does not. The reality is that we care because we love. Nature appealed to our hearts, when we were children, long before it appealed to our heads, let alone our pockets. Yet we seem to believe we can persuade people to change their lives through the cold, mechanical power of reason, supported by statistics.

I see the encyclical by Pope Francis, which will be published on Thursday, as a potential turning point. He will argue that not only the physical survival of the poor, but also our spiritual welfare depends on the protection of the natural world; and in both respects he is right.

I don’t mean that a belief in God is the answer to our environmental crisis. Among Pope Francis’s opponents is the evangelical US-based Cornwall Alliance for the Stewardship of Creation, which has written to him arguing that we have a holy duty to keep burning fossil fuel, as “the heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament proclaims his handiwork”. It also insists that exercising the dominion granted to humankind in Genesis means tilling “the whole Earth”, transforming it “from wilderness to garden and ultimately to garden city”.

There are similar tendencies within the Vatican. Cardinal George Pell, its head of finance, currently immersed in a scandal involving paedophile priests in Australia, is a prominent climate change denier. His lecture to the Global Warming Policy Foundation was the usual catalogue of zombie myths (discredited claims that keep resurfacing), nonsequiturs and outright garbage championing, for example, the groundless claim that undersea volcanoes could be responsible for global warming. There are plenty of senior Catholics seeking to undermine the pope’s defence of the living world, which could explain why a draft of his encyclical was leaked. What I mean is that Pope Francis, a man with whom I disagree profoundly on matters such as equal marriage and contraception, reminds us that the living world provides not only material goods and tangible services, but is also essential to other aspects of our wellbeing. And you don’t have to believe in God to endorse that view.

In his beautiful book The Moth Snowstorm, Michael McCarthy suggests that a capacity to love the natural world, rather than merely to exist within it, might be a uniquely human trait. When we are close to nature, we sometimes find ourselves, as Christians put it, surprised by joy: “A happiness with an overtone of something more, which we might term an elevated or, indeed, a spiritual quality.”

He believes we are wired to develop a rich emotional relationship with nature. A large body of research suggests that contact with the living world is essential to our psychological and physiological wellbeing. (A paper published this week, for example, claims that green spaces around city schools improve children’s mental performance.)

This does not mean that all people love nature; what it means, McCarthy proposes, is that there is a universal propensity to love it, which may be drowned out by the noise that assails our minds. As I’ve found while volunteering with the outdoor education charity Wide Horizons, this love can be provoked almost immediately, even among children who have never visited the countryside before. Nature, McCarthy argues, remains our home, “the true haven for our psyches”, and retains an astonishing capacity to bring peace to troubled minds.

Acknowledging our love for the living world does something that a library full of papers on sustainable development and ecosystem services cannot: it engages the imagination as well as the intellect. It inspires belief; and this is essential to the lasting success of any movement.

Is this a version of the religious conviction from which Pope Francis speaks? Or could his religion be a version of a much deeper and older love? Could a belief in God be a way of explaining and channelling the joy, the burst of love that nature sometimes inspires in us? Conversely, could the hyperconsumption that both religious and secular environmentalists lament be a response to ecological boredom: the void that a loss of contact with the natural world leaves in our psyches?

Of course, this doesn’t answer the whole problem. If the acknowledgement of love becomes the means by which we inspire environmentalism in others, how do we translate it into political change? But I believe it’s a better grounding for action than pretending that what really matters to us is the state of the economy. By being honest about our motivation we can inspire in others the passions that inspire us.

Who wants to see the living world destroyed? Who wants an end to birdsong, bees and coral reefs, the falcon’s stoop, the salmon’s leap? Who wants to see the soil stripped from the land, the sea rimed with rubbish?

No one. And yet it happens. Seven billion of us allow fossil fuel companies to push shut the narrow atmospheric door through which humanity stepped. We permit industrial farming to tear away the soil, banish trees from the hills, engineer another silent spring. We let the owners of grouse moors, 1% of the 1%, shoot and poison hen harriers, peregrines and eagles. We watch mutely as a small fleet of monster fishing ships trashes the oceans.

Why are the defenders of the living world so ineffective? It is partly, of course, that everyone is complicit; we have all been swept off our feet by the tide of hyperconsumption, our natural greed excited, corporate propaganda chiming with a will to believe that there is no cost. But perhaps environmentalism is also afflicted by a deeper failure: arising possibly from embarrassment or fear, a failure of emotional honesty

.

FacebookTwitterPinterest ‘We have all been swept off our feet by the tide of hyperconsumption, our natural greed excited, corporate propaganda chiming with a will to believe that there is no cost’.

I have asked meetings of green-minded people to raise their hands if they became defenders of nature because they were worried about the state of their bank accounts. Never has one hand appeared. Yet I see the same people base their appeal to others on the argument that they will lose money if we don’t protect the natural world.

Such claims are factual, but they are also dishonest: we pretend that this is what animates us, when in most cases it does not. The reality is that we care because we love. Nature appealed to our hearts, when we were children, long before it appealed to our heads, let alone our pockets. Yet we seem to believe we can persuade people to change their lives through the cold, mechanical power of reason, supported by statistics.

I see the encyclical by Pope Francis, which will be published on Thursday, as a potential turning point. He will argue that not only the physical survival of the poor, but also our spiritual welfare depends on the protection of the natural world; and in both respects he is right.

I don’t mean that a belief in God is the answer to our environmental crisis. Among Pope Francis’s opponents is the evangelical US-based Cornwall Alliance for the Stewardship of Creation, which has written to him arguing that we have a holy duty to keep burning fossil fuel, as “the heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament proclaims his handiwork”. It also insists that exercising the dominion granted to humankind in Genesis means tilling “the whole Earth”, transforming it “from wilderness to garden and ultimately to garden city”.

There are similar tendencies within the Vatican. Cardinal George Pell, its head of finance, currently immersed in a scandal involving paedophile priests in Australia, is a prominent climate change denier. His lecture to the Global Warming Policy Foundation was the usual catalogue of zombie myths (discredited claims that keep resurfacing), nonsequiturs and outright garbage championing, for example, the groundless claim that undersea volcanoes could be responsible for global warming. There are plenty of senior Catholics seeking to undermine the pope’s defence of the living world, which could explain why a draft of his encyclical was leaked. What I mean is that Pope Francis, a man with whom I disagree profoundly on matters such as equal marriage and contraception, reminds us that the living world provides not only material goods and tangible services, but is also essential to other aspects of our wellbeing. And you don’t have to believe in God to endorse that view.

In his beautiful book The Moth Snowstorm, Michael McCarthy suggests that a capacity to love the natural world, rather than merely to exist within it, might be a uniquely human trait. When we are close to nature, we sometimes find ourselves, as Christians put it, surprised by joy: “A happiness with an overtone of something more, which we might term an elevated or, indeed, a spiritual quality.”

He believes we are wired to develop a rich emotional relationship with nature. A large body of research suggests that contact with the living world is essential to our psychological and physiological wellbeing. (A paper published this week, for example, claims that green spaces around city schools improve children’s mental performance.)

This does not mean that all people love nature; what it means, McCarthy proposes, is that there is a universal propensity to love it, which may be drowned out by the noise that assails our minds. As I’ve found while volunteering with the outdoor education charity Wide Horizons, this love can be provoked almost immediately, even among children who have never visited the countryside before. Nature, McCarthy argues, remains our home, “the true haven for our psyches”, and retains an astonishing capacity to bring peace to troubled minds.

Acknowledging our love for the living world does something that a library full of papers on sustainable development and ecosystem services cannot: it engages the imagination as well as the intellect. It inspires belief; and this is essential to the lasting success of any movement.

Is this a version of the religious conviction from which Pope Francis speaks? Or could his religion be a version of a much deeper and older love? Could a belief in God be a way of explaining and channelling the joy, the burst of love that nature sometimes inspires in us? Conversely, could the hyperconsumption that both religious and secular environmentalists lament be a response to ecological boredom: the void that a loss of contact with the natural world leaves in our psyches?

Of course, this doesn’t answer the whole problem. If the acknowledgement of love becomes the means by which we inspire environmentalism in others, how do we translate it into political change? But I believe it’s a better grounding for action than pretending that what really matters to us is the state of the economy. By being honest about our motivation we can inspire in others the passions that inspire us.

Friday, 16 January 2015

Perspective on Charlie Hebdo, Peshawar killings; In maya, the killer and the killed

Jan 14, 2015 12:21 AM , By Devdutt Pattanaik in The Hindu |

Emotional violence is not measurable. Physical violence is, which makes it a crime that can be proven and hence a greater crime, especially when emotional violence is directed at something as notional as religion

When the Pandavas invited Krishna to be the chief guest at the coronation of Yudhishtira, Shishupala felt insulted and began abusing Krishna. Everyone became upset, but not Krishna who was listening calmly. However, after the hundredth insult, Krishna hurled his razor-sharp discus and beheaded Shishupala. For the limit of forgiveness was up.

Charlie Hebdo, a French satirical weekly, published cartoons; offensive cartoons that I have never seen, and would never have, had someone not killed its staff. With that Charlie became a person, a victim, a martyr to the cause of the freedom of expression. We became heroes by condemning the killing. And so millions have walked in Paris to declare that they are Charlie.

Will there be a march where people identify themselves with Charlie’s killers? Is that allowed? Who are the killers? Muslim, bad Muslim, mad Muslim, un-Islamic Muslim? The editorials are undecided, as in the attack in Peshawar on schoolchildren. The victims there did not even provoke; their parents probably did.

The provocation in Charlie’s case was this: perceived insult to the Prophet Muhammad, hence Islam. Charlie, however, was functioning within the laws of a land renowned for the phrase, “Liberty, Equality and Brotherhood!” Islam is also about brotherhood (Ummah, in Arabic) and equality, though not so much about liberty since Islam does mean submission, a submission to the word of god that brings peace.

Managing the measurable

The two siblings, believers in equality and their own version of liberty decided to hurt each other, one emotionally, the other physically. Emotional violence is not measurable. Physical violence is. That makes the latter a crime that can be proven, hence a greater crime, especially when emotional violence is directed at something as notional as religion. Because we are scientific, you see.

The two siblings, believers in equality and their own version of liberty decided to hurt each other, one emotionally, the other physically. Emotional violence is not measurable. Physical violence is. That makes the latter a crime that can be proven, hence a greater crime, especially when emotional violence is directed at something as notional as religion. Because we are scientific, you see.

And here is the problem — measurement, that cornerstone of science and objectivity.

We can manage the measurable. But what about the non-measurable? Does it matter at all? Emotions cannot be measured. The mind cannot be measured, which is why purists refer to psychology and behavioural science as pseudoscience. God cannot be measured. For the scientist, god is therefore not fact. It is at best a notion. This annoys the Muslim, for he/she believes in god, and for him/her god is fact, not measurable fact, but fact nevertheless. It is subjective truth. My truth. Does it matter?

Where do we locate subjective truth: as fact or fiction? Some people have given themselves the “Freedom of Expression” and others have given themselves a “God, who is the one True God.” Both are subjective truths. They shape our reality. They matter. But we just do not know how to locate them, for they are not measurable.

We cannot measure the hurt Charlie’s cartoons caused the Muslim community. We cannot measure the Muslim community’s sensitivity or over-sensitivity. But we can measure the outcome of the actions of the killers. We can therefore easily condemn violence. That it caused hurt, rage, humiliation, enough for some people to grab guns, is a non-measurable assumption, a belief. Belief is a joke for the rational atheist.

The intellectual can hurt with his/her words. The soldier can hurt with his/her weapons. We live in the world where the former is acceptable, even encouraged. The latter is not. It is a neo-Brahminism that the global village has adopted. Those who think and speak are superior to those who beat and kill, even if the wounds created by word-missiles can be deeper, last longer and fester forever. Gandhi, the non-violent sage, is thus pitted against Godse, the violent brute. I, the intellectual, have the right to provoke; but you, the barbarian who only knows to wield violence, have no right to get provoked and respond the only way you know how to. If you do get provoked, you have to respond in my language, not yours, brain not brawn, because the brain is superior. I, the intellectual Brahmin, make the rules. Did you not know that?

Non-violence is the new god, the one true god. When we say violence, we are actually referring only to the physical violence of the barbarian. The mental violence of the intellectual elite is not considered violence. So, one has sanction to mock Hinduism intellectually on film (PK by Rajkumar Hirani and Aamir Khan) and in books (The Hindus: An Alternative History by Wendy Doniger), but those who demand the film be banned and the books be pulped are brutes, barbarians, enemies of civic discourse, who resort to violence. They are not as bad as the Charlie killers, but seem to be on the same path.

Role of the thinker

We refuse to see arguments as brutal bloodless warfare, mental warfare. We don’t see debating societies as battlegrounds. Mental torture, we are told, is merely a concept, not truth: difficult to measure hence prove. The husband who mentally tortures can never be caught; the husband who strikes the wife can be caught. We empathise with the latter, not the former (she is over-sensitive, we rationalise). Should the mentally tortured wife kill her husband, it is she who will be hauled to jail, not the husband. Her crime can be proved. Not his.

We refuse to see arguments as brutal bloodless warfare, mental warfare. We don’t see debating societies as battlegrounds. Mental torture, we are told, is merely a concept, not truth: difficult to measure hence prove. The husband who mentally tortures can never be caught; the husband who strikes the wife can be caught. We empathise with the latter, not the former (she is over-sensitive, we rationalise). Should the mentally tortured wife kill her husband, it is she who will be hauled to jail, not the husband. Her crime can be proved. Not his.

The thinker we are told is not a doer. The killings provoked by the thinker thus goes unnoticed. The thinker — the seed of the violence — chuckles as the barbarian, whose only vocabulary is physical, will be caught and punished while mental warfare will go on with brutal precision. When the ill-equipped barbarian even attempts to fight back using words, we mock him as the troll.

In Sanskrit, the root of the world maya is ma, to measure. We translate the word as illusion or delusion but it technically means a world constructed through measurement. Thus, the scientific word, the rational world, based on measurement, is maya. And that is neither a good or bad thing. It is not a judgement. It is an observation. A world based on measurement will focus on the tangible and lose perspective of the intangible. It will assume measured truth as Truth, rather than limited truth.

Those who felt gleeful self-righteousness in mocking the Prophet are in maya. So are those who took such serious offence to it. The killer is in maya and so is the killed. Those who judge one as the victim and the other as the villain are also in maya. We all live in our constructed realities, some based on measurement, some indifferent to measurement, each one eager to dismiss the other, rendering them irrelevant: The other is the barbarian who needs to be educated. The other is also the intellectual who is best killed.

Essentially, maya makes us to judge. For when we measure, we wonder which is small and what is big, what is up and what is down, what is right and what is wrong, what matters and what does not matter. Different measuring scales lead to different judgments. Wendy Doniger is convinced she is the hero, and martyr, who fights for the subaltern Indian in her writings. Dinanath Batra is convinced he is the hero who opposes her wilful misunderstanding of sanatana dharma. Baba Ramdev feels he has a right to demand the banning of PK. And the producers of the film respond predictably about the freedom of speech and rationality, as they laugh their way to the bank. Everyone is right, in his or her maya.

Every action has consequences. And consequences are good and bad only in hindsight. The age of Enlightenment was also the age of Colonisation. The most brutal wars of the 20th century, from the world wars to the Cold Wars, were secular. Non-violent thought manifests itself in non-violent words which give rise to violent action. The fruit is measurable, not the seed. To separate seed from fruit, thought from action, is like separating stimulus from response. It results in a wrong diagnosis and a wrong prescription. The killer does not kill thought. The thought creates more killers.

What goes around always comes around. Outrage over violence feeds outrage over cartoons. Hindu philosophy (not Hindutva philosophy) calls this karma. We don’t want to break the cycle by letting go of either non-violent outrage or violent protests. Ideas such as maya and karma annoy the westernised mind for they disempower them: they who are determined to save the world with measuring tools dismiss astute observation of the human condition as fatalism.

In his past life, Shishupala was the doorkeeper Jaya of Vaikuntha who was cursed by the Sanat rishis that he would be born on earth, away from Vishnu, for daring to block their entry. The doorkeeper Jaya argued that he was doing his job but the curse stuck and Jaya was reborn as Shishupala. Vishnu had promised to liberate him and to expedite his departure, Shishupala practised viparit-bhakti, reverse-devotion, displaying love through abuse. So he insulted Krishna, knowing full well that Krishna was Vishnu and would be forced to act. There is a limit to forgiveness. But there should be no limit to love.

Tuesday, 23 December 2014

Christmas is a face-off between people who are spiritual and people who are consumerist

How do you formulate an anti-consumerist worldview that doesn’t involve becoming a killjoy?

Christmas is a face-off between people who are spiritual and people who are consumerist. The consumerists never call themselves that, they’re just really keen to let you know that they don’t believe in God. The spiritual ones never call themselves spiritual, they are just very anti-consumerist. It’s the dialectic method of identity building: I hate crackers and piped music, ergo I am deep; I hate superstition and unprovable things, ergo I am fun. It’s like a zero-sum game in which the shops helpfully give the spiritualists something to kick against, and the churches, especially with their midnight shenanigans, give the consumerists something to laugh at.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t leave you much room for manoeuvre if you are both anti-consumerist and an atheist. Pretty much everything you say will deliver you into the hands of the wrong ally. Up until now, I have always just succumbed to one side, in order to avoid getting crushed by the competing plates. Between about 1983 and 2013, assuming myself – on the final throw of the dice – to be more of an atheist than an anti-consumerist, I swallowed the shop-fest whole. I remember standing in Marks & Spencer buying a slipper bag for my uncle, crying with laughter at the scope of the needlessness. Who needs a bag to put their slippers in? It’s like having a special wallet for handkerchieves. Probably, if he’d lived a bit longer, I’d have bought him one of those too. None of this ever struck me as at all obscene; it was all at one remove from obscenity, like a cartoon of someone accidentally chopping off their arm.

But having kids has tipped me over the edge. It isn’t their spiritual wellbeing I’m worried about – they have grandparents for that. It’s the volume of plastic tat I have to throw out every year, to make way for the next tranche of plastic tat. It’s like an anxiety dream, this act: shovelling gigantic, brightly coloured items that have detained nobody for one second longer than the time it takes to render them incomplete or no longer working. They are almost new, and completely pointless. I don’t want to blight another household with them, but I can’t face putting them in the bin, so the whole lot from last year spent six months in a sort of staging post, some inconvenient place while I waited for some other person to throw them out for me. If they’re battery powered it’s 10 times worse, because the added complexity is like an accusation. They are all battery powered.

This is when you’re faced with the question that you should have squared up to 20 years ago: how do you formulate an anti-consumerist worldview that doesn’t involve becoming a killjoy? How do you eschew consumption while still maintaining your spiritual hollowness? The people buying the plastic have annexed the space “fun”, while the people with the baby in the manger have appropriated “thought”. I have no ideological home in this season. But I do love the drinking.

Monday, 14 July 2014

The Science Delusion by Rupert Sheldrake - A review

The Science Delusion - Sheldrake

The Day the Universe Changed - James Burke

We must find a new way of understanding human beings

Dogs: do they really know when you're coming home? Photograph: Laurie and Charles/Getty Images

The unlucky fact that our current form of mechanistic materialism rests on muddled, outdated notions of matter isn't often mentioned today. It's a mess that can be ignored for everyday scientific purposes, but for our wider thinking it is getting very destructive. We can't approach important mind-body topics such as consciousness or the origins of life while we still treat matter in 17th-century style as if it were dead, inert stuff, incapable of producing life. And we certainly can't go on pretending to believe that our own experience – the source of all our thought – is just an illusion, which it would have to be if that dead, alien stuff were indeed the only reality.

We need a new mind-body paradigm, a map that acknowledges the many kinds of things there are in the world and the continuity of evolution. We must somehow find different, more realistic ways of understanding human beings – and indeed other animals – as the active wholes that they are, rather than pretending to see them as meaningless consignments of chemicals.

Rupert Sheldrake, who has long called for this development, spells out this need forcibly in his new book. He shows how materialism has gradually hardened into a kind of anti-Christian faith, an ideology rather than a scientific principle, claiming authority to dictate theories and to veto inquiries on topics that don't suit it, such as unorthodox medicine, let alone religion. He shows how completely alien this static materialism is to modern physics, where matter is dynamic. And, to mark the strange dilemmas that this perverse fashion poses for us, he ends each chapter with some very intriguing "Questions for Materialists", questions such as "Have you been programmed to believe in materialism?", "If there are no purposes in nature, how can you have purposes yourself?", "How do you explain the placebo response?" and so on.

In short, he shows just how unworkable the assumptions behind today's fashionable habits have become. The "science delusion" of his title is the current popular confidence in certain fixed assumptions – the exaltation of today's science, not as the busy, constantly changing workshop that it actually is but as a final, infallible oracle preaching a crude kind of materialism.

In trying to replace it he needs, of course, to suggest alternative assumptions. But here the craft of paradigm-building has chronic difficulties. Our ancestors only finally stopped relying on the familiar astrological patterns when they had grown accustomed to machine-imagery instead – first becoming fascinated by the clatter of clockwork and later by the ceaseless buzz of computers, so that they eventually felt sure that they were getting new knowledge. Similarly, if we are told today that a mouse is a survival-machine, or that it has been programmed to act as it does, we may well feel that we have been given a substantial explanation, when all we have really got is one more optional imaginative vision – "you can try looking at it this way".

That is surely the right way to take new suggestions – not as rival theories competing with current ones but as extra angles, signposts towards wider aspects of the truth. Sheldrake's proposal that we should think of natural regularities as habits rather than as laws is not just an arbitrary fantasy. It is a new analogy, brought in to correct what he sees as a chronic exaggeration of regularity in current science. He shows how carefully research conventions are tailored to smooth out the data, obscuring wide variations by averaging many results, and, in general, how readily scientists accept results that fit in with their conception of eternal laws.

He points out too, that the analogy between natural regularities and habit is not actually new. Several distinctly non-negligible thinkers – CS Peirce, Nietzsche, William James,AN Whitehead – have already suggested it because they saw the huge difference between the kind of regularity that is found among living things and the kind that is expected of a clock or a calcium atom.

Whether or no we want to follow Sheldrake's further speculations on topics such asmorphic resonance, his insistence on the need to attend to possible wider ways of thinking is surely right. And he has been applying it lately in fields that might get him an even wider public. He has been making claims about two forms of perception that are widely reported to work but which mechanists hold to be impossible: a person's sense of being looked at by somebody behind them, and the power of animals – dogs, say – to anticipate their owners' return. Do these things really happen?

Sheldrake handles his enquiries soberly. People and animals do, it seems, quite often perform these unexpected feats, and some of them regularly perform them much better than others, which is perhaps not surprising. He simply concludes that we need to think much harder about such things.

Orthodox mechanistic believers might have been expected to say what they think is wrong with this research. In fact, not only have scientists mostly ignored it but, more interestingly still, two professed champions of scientific impartiality, Lewis Wolpert and Richard Dawkins, who did undertake to discuss it, reportedly refused to look at the evidence (see two pages in this book). This might indeed be a good example of what Sheldrake means by the "science delusion".

Friday, 28 February 2014

It’s no good, Dawkins. No one’s going to abandon religion because some atheist is banging on at them about science

Mark Steel in The Independent

There’s a religious slot broadcast every morning on the radio, called Thought for the Day, and it’s marvellous. Because it usually involves some bishop telling you what he did the day before, and shovelling Jesus into it somehow. So it will go: “Last night I was watching an episode of Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares, in which a poor hapless restaurateur once again found himself on the wrong end of Gordon’s somewhat ribald invective. And I began to think to myself ‘Isn’t this a bit like Jesus’? Because Jesus too went out for supper one night, and that turned into a bit of a nightmare. Good morning.”

The fact that this quaint tradition endures with few complaints, despite a campaign led by the National Secular Society, suggests that the modern atheists are losing. So does the popularity of The Book of Mormon, the gloriously blasphemous musical I’ve finally seen, which, despite a swearing, camp Jesus and a plot revolving around religion being made-up nonsense, is strangely affectionate towards religion. You’re invited to judge the evangelists on what they do, rather than on what they believe, and that may be a vital part of its success, compared with the modern atheists whose attitude is: “Of COURSE Jesus didn’t rise from the dead, you idiots.”

Richard Dawkins, for example, complained that a Muslim political writer wasn’t a “serious journalist” because he “believes Mohamed flew to heaven on a winged horse”. I suppose if Dawkins had been in Washington when Martin Luther King made his famous speech, he’d have shouted: “Never mind your dream, how can Jonah have lived in a whale, you silly Christian knob?”

Followers of this ideal just can’t have it that some people are religious, even if they’re not doing any harm. I expect that during Ramadan they wander around Muslim areas in daylight shoving sandwiches in Muslims’ mouths, while reading from a biological paper on the workings of the digestive system.

One flaw in this approach is that it isn’t likely to win many converts. In all the debates in which Dawkins has argued with believers, there can’t have been many occasions when someone has said: “Ah NOW I see: we’re organisms composed of a complex series of particles. So that goddess with all the arms must be a load of bollocks.”

He can’t seem to grasp that what’s obvious to him might not look that way if you’ve been brought up in Catholic rural Spain or on the banks of the Ganges, so dealing with the intricacies of people’s ideas requires more than yelling science at them. If Dawkins were asked to treat an anorexic, he’d say: “This will be easy,” and shout, “Look – you’re NOT FAT, I’ll pick you up and chuck you over the wardrobe. THEN you’ll calculate that a man of my years couldn’t throw an adult unless they were in need of fattening up. So get these down you – they’re some pork pies I’ve got left over from Ramadan.”

The modern atheist often points to atrocities carried out by religious institutions, such as the tyranny of the Taliban or the child abuse of the Catholic Church, but isn’t it the actions of these people that are vile, not the religion itself? Unless your attitude is: “Those priests are a disgrace. They sexually abused children, covered it up for decades, then to top it all they give out stupid wafers in their service. How sick can you get”?

The contradictions of religion are certainly confusing. I spent a morning at a Sikh temple recently, where 4,000 free meals are provided for anyone who wants one, and hypnotic musicians play all day amid an addictive tranquillity. Everyone you meet exudes joy and respect, until I thought: “I reckon I could be a Sikh.” Then an elder informed me of the guru who fought for the Sikh people with such courage, that when his head was chopped off he carried on fighting for the rest of the day, blessed as he was by God. And if I’m honest, I think that’s where we had to agree to differ.

Even so, there’s so much to experience and discuss with followers at this temple – the process that led them from the Punjab to west London, the food, customs, community and music – so to start your acquaintance by explaining to them that you can’t run around without a head, maybe by performing a series of experiments with goats on the steps of the temple, would cut you off from any of that. In any case, if you turned up at Richard Dawkins’s house with 4,000 mates, I’d be surprised if you all got a meal out of him.

It’s almost as if the modern atheist is in agreement with the religious fundamentalist that a person’s attitude towards God is the most important aspect of their character.

This may be why, even among atheists, the strident anti-religious stance of those like Richard Dawkins appears less attractive than The Book of Mormon, whose creators said: “We wanted to write a love letter from atheists to religion.”

That must be the most heartening attitude of all, though if you were to take Cliff Richard and Abu Hamza to see it, they would probably literally explode in a fireball. Then millions from round the world would flock to see the site of such a miracle.

Friday, 27 December 2013

Why Atheists need rituals too

To move many away from religion, atheism has to weave itself into the social fabric and shed its image of dour grumpiness

- Suzanne Moore for New Humanist, part of the Guardian Comment Network

- theguardian.com,

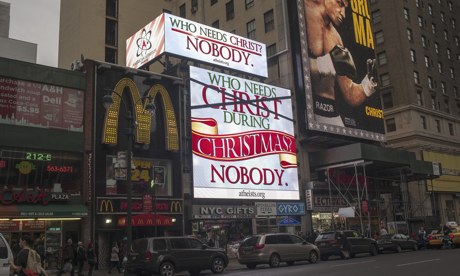

A billboard sponsored by the American Atheists organisation in New York. Photograph: Richard Levine/Demotix/Corbis

The last time I put my own atheism through the spin cycle rather than simply wiping it clean was when I wanted to make a ceremony after the birth of my third child. Would it be a blessing? From who? What does the common notion of a new baby as a gift mean? How would we make it meaningful to the people we invited who were from different faiths? And, importantly, what would it look like?

One of the problems I have with the New Atheism is that it fixates on ethics, ignoring aesthetics at its peril. It tends also towards atomisation, relying on abstracts such as "civic law" to conjure a collective experience. But I love ritual, because it is through ritual that we remake and strengthen our social bonds. As I write, down the road there is a memorial being held for Lou Reed, hosted by the local Unitarian church. Most people there will have no belief in God but will feel glad to be part of a shared appreciation of a man whose god was rock'n'roll.

When it came to making a ceremony, I really did not want the austerity of some humanist events I have attended, where I feel the sensual world is rejected. This is what I mean about aesthetics. Do we cede them to the religious and just look like a bunch of Calvinists? I found myself turning to flowers, flames and incense. Is there anything more beautiful than the offerings made all over the world, of tiny flames and blossom on leaves floating on water?

Already, I am revealing a kind of neo-paganism that hardcore rationalist will find unacceptable. But they find most human things unacceptable. For me, not believing in God does not mean one has to forgo poetry, magic, the chaos of ritual, the remaking of shared bonds. I fear ultra-orthodox atheism has come to resemble a rigid and patriarchal faith itself.

This is not about reclaiming "feeling" as female and reason as male. Put simply, it seems to be fundamentally human to seek narratives, find patterns and create rituals to include others in the meanings we make. If we want a more secular society – and we most certainly do – there is nothing wrong with making it look and feel good.

Yet as I attend yet another overpoweringly religious funeral of a woman who was not religious – as I did recently – I see that people do not know what else to do. They turn to organised religion's hatch 'em, match 'em and dispatch 'em certainties. For while humanists work hard to create new ceremonies, many find them vapid. Funerals are problematic, as one is bound by law to dispose of the body in a certain way. I always remember the startled look of the platitudinous young vicar who visited our house after my grandad died, when my mum said, "Don't come round here with your mumbo-jumbo. If I had my way I'd put him in the vegetable patch with some lime on him."

Unless someone has planned their own funeral it can be difficult, but naming or partnership ceremonies are a chance to think about what it is we are celebrating. A new person, love, being part of a community. For my daughter's, we pieced together what we wanted, but I found some of the humanist suggestions strange. "Odd parents" for godparents? No thanks. I guess it's just a matter of taste.

What, then, makes ceremony powerful? It is the recognition of common humanity; and it is very hard to do this without borrowing from traditional symbols. We need to create a space outside of everyday life to do this. We can call it sacred space but the demarcation of special times or spaces is not the prerogative only of the religious. One of the best ceremonies of late was the opening of the Olympics, where Danny Boyle created a massive spectacle that communicated shared values in a non-religious way. It was big-budget joy. Most of us don't have such a budget but there has to be some nuance here. We may not have God. We may find the fuzziness of new age thinking with its emphasis on "nature" and "spirit" impure, but to dismiss the human need to express transcendence and connection with others as stupid is itself stupid.

Our ceremony had flowers and fires and Dylan, a Baptist minister and the Jabberwocky, half-Mexican siblings and symbols, a Catholic grandparent reading her prayer, a Muslim godparent and kids off their heads on helium at the party. A right old mishmash, then, but our mishmash.

In saying this I realise I am not a good atheist. Rather like mothering, perhaps I can only be a good enough one. But to move many away from religion, a viable atheism has to weave itself into the social fabric and shed this image of dour grumpiness. What can be richer than the celebration of our common humanity? Here is magic, colour, poetry. Life.

Saturday, 16 November 2013

Why even atheists should be praying for Pope Francis

Francis could replace Obama as the pin-up on every liberal and leftist wall. He is now the world's clearest voice for change

'On Thursday, Pope Francis visited the Italian president, arriving in a blue Ford Focus, with not a blaring siren to be heard.' Photograph: Gregorio Borgia/AP

That Obama poster on the wall, promising hope and change, is looking a little faded now. The disappointments, whether over drone warfare or a botched rollout of healthcare reform, have left the world's liberals and progressives searching for a new pin-up to take the US president's place. As it happens, there's an obvious candidate: the head of an organisation those same liberals and progressives have long regarded as sexist, homophobic and, thanks to a series of child abuse scandals, chillingly cruel. The obvious new hero of the left is the pope.

Only installed in March, Pope Francis has already become a phenomenon. His is the most talked-about name on the internet in 2013, ranking ahead of "Obamacare" and "NSA". In fourth place comes Francis's Twitter handle, @Pontifex. In Italy, Francesco has fast become the most popular name for new baby boys. Rome reports a surge in tourist numbers, while church attendance is said to be up – both trends attributed to "the Francis effect".

His popularity is not hard to fathom. The stories of his personal modesty have become the stuff of instant legend. He carries his own suitcase. He refused the grandeur of the papal palace, preferring to live in a simple hostel. When presented with the traditional red shoes of the pontiff, he declined; instead he telephoned his 81-year-old cobbler in Buenos Aires and asked him to repair his old ones. On Thursday, Francis visited the Italian president – arriving in a blue Ford Focus, with not a blaring siren to be heard.

Some will dismiss these acts as mere gestures, even publicity stunts. But they convey a powerful message, one of almost elemental egalitarianism. He is in the business of scraping away the trappings, the edifice of Vatican wealth accreted over centuries, and returning the church to its core purpose, one Jesus himself might have recognised. He says he wants to preside over "a poor church, for the poor". It's not the institution that counts, it's the mission.

All this would warm the heart of even the most fervent atheist, except Francis has gone much further. It seems he wants to do more than simply stroke the brow of the weak. He is taking on the system that has made them weak and keeps them that way.

"My thoughts turn to all who are unemployed, often as a result of a self-centred mindset bent on profit at any cost," he tweeted in May. A day earlier he denounced as "slave labour" the conditions endured by Bangladeshi workers killed in a building collapse. In September he said that God wanted men and women to be at the heart of the world and yet we live in a global economic order that worships "an idol called money".

There is no denying the radicalism of this message, a frontal and sustained attack on what he calls "unbridled capitalism", with its "throwaway" attitude to everything from unwanted food to unwanted old people. His enemies have certainly not missed it. If a man is to be judged by his opponents, note that this week Sarah Palin denounced him as "kind of liberal" while the free-market Institute of Economic Affairs has lamented that this pope lacks the "sophisticated" approach to such matters of his predecessors. Meanwhile, an Italian prosecutor has warned that Francis's campaign against corruption could put him in the crosshairs of that country's second most powerful institution: the mafia.

As if this weren't enough to have Francis's 76-year-old face on the walls of the world's student bedrooms, he also seems set to lead a church campaign on the environment. He was photographed this week with anti-fracking activists, while his biographer, Paul Vallely, has revealed that the pope has made contact with Leonardo Boff, an eco-theologian previously shunned by Rome and sentenced to "obsequious silence" by the office formerly known as the "Inquisition". An encyclical on care for the planet is said to be on the way.

Many on the left will say that's all very welcome, but meaningless until the pope puts his own house in order. But here, too, the signs are encouraging. Or, more accurately, stunning. Recently, Francis told an interviewer the church had become "obsessed" with abortion, gay marriage and contraception. He no longer wanted the Catholic hierarchy to be preoccupied with "small-minded rules". Talking to reporters on a flight – an occurrence remarkable in itself – he said: "If a person is gay and seeks God and has good will, who am I to judge?" His latest move is to send the world's Catholics a questionnaire, seeking their attitude to those vexed questions of modern life. It's bound to reveal a flock whose practices are, shall we say, at variance with Catholic teaching. In politics, you'd say Francis was preparing the ground for reform.

Witness his reaction to a letter – sent to "His Holiness Francis, Vatican City" – from a single woman, pregnant by a married man who had since abandoned her. To her astonishment, the pope telephoned her directly and told her that if, as she feared, priests refused to baptise her baby, he would perform the ceremony himself. (Telephoning individuals who write to him is a Francis habit.) Now contrast that with the past Catholic approach to such "fallen women", dramatised so powerfully in the current film Philomena. He is replacing brutality with empathy.

Of course, he is not perfect. His record in Argentina during the era of dictatorship and "dirty war" is far from clean. "He started off as a strict authoritarian, reactionary figure," says Vallely. But, aged 50, Francis underwent a spiritual crisis from which, says his biographer, he emerged utterly transformed. He ditched the trappings of high church office, went into the slums and got his hands dirty.

Now inside the Vatican, he faces a different challenge – to face down the conservatives of the curia and lock in his reforms, so that they cannot be undone once he's gone. Given the guile of those courtiers, that's quite a task: he'll need all the support he can get.

Some will say the world's leftists and liberals shouldn't hanker for a pin-up, that the urge is infantile and bound to end in disappointment. But the need is human and hardly confined to the left: think of the Reagan and Thatcher posters that still adorn the metaphorical walls of conservatives, three decades on. The pope may have no army, no battalions or divisions, but he has a pulpit – and right now he is using it to be the world's loudest and clearest voice against the status quo. You don't have to be a believer to believe in that.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)

.png)