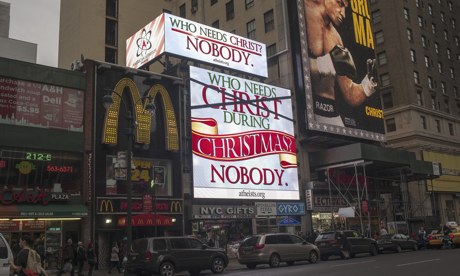

A billboard sponsored by the American Atheists organisation in New York. Photograph: Richard Levine/Demotix/Corbis

The last time I put my own atheism through the spin cycle rather than simply wiping it clean was when I wanted to make a ceremony after the birth of my third child. Would it be a blessing? From who? What does the common notion of a new baby as a gift mean? How would we make it meaningful to the people we invited who were from different faiths? And, importantly, what would it look like?

One of the problems I have with the New Atheism is that it fixates on ethics, ignoring aesthetics at its peril. It tends also towards atomisation, relying on abstracts such as "civic law" to conjure a collective experience. But I love ritual, because it is through ritual that we remake and strengthen our social bonds. As I write, down the road there is a memorial being held for Lou Reed, hosted by the local Unitarian church. Most people there will have no belief in God but will feel glad to be part of a shared appreciation of a man whose god was rock'n'roll.

When it came to making a ceremony, I really did not want the austerity of some humanist events I have attended, where I feel the sensual world is rejected. This is what I mean about aesthetics. Do we cede them to the religious and just look like a bunch of Calvinists? I found myself turning to flowers, flames and incense. Is there anything more beautiful than the offerings made all over the world, of tiny flames and blossom on leaves floating on water?

Already, I am revealing a kind of neo-paganism that hardcore rationalist will find unacceptable. But they find most human things unacceptable. For me, not believing in God does not mean one has to forgo poetry, magic, the chaos of ritual, the remaking of shared bonds. I fear ultra-orthodox atheism has come to resemble a rigid and patriarchal faith itself.

This is not about reclaiming "feeling" as female and reason as male. Put simply, it seems to be fundamentally human to seek narratives, find patterns and create rituals to include others in the meanings we make. If we want a more secular society – and we most certainly do – there is nothing wrong with making it look and feel good.

Yet as I attend yet another overpoweringly religious funeral of a woman who was not religious – as I did recently – I see that people do not know what else to do. They turn to organised religion's hatch 'em, match 'em and dispatch 'em certainties. For while humanists work hard to create new ceremonies, many find them vapid. Funerals are problematic, as one is bound by law to dispose of the body in a certain way. I always remember the startled look of the platitudinous young vicar who visited our house after my grandad died, when my mum said, "Don't come round here with your mumbo-jumbo. If I had my way I'd put him in the vegetable patch with some lime on him."

Unless someone has planned their own funeral it can be difficult, but naming or partnership ceremonies are a chance to think about what it is we are celebrating. A new person, love, being part of a community. For my daughter's, we pieced together what we wanted, but I found some of the humanist suggestions strange. "Odd parents" for godparents? No thanks. I guess it's just a matter of taste.

What, then, makes ceremony powerful? It is the recognition of common humanity; and it is very hard to do this without borrowing from traditional symbols. We need to create a space outside of everyday life to do this. We can call it sacred space but the demarcation of special times or spaces is not the prerogative only of the religious. One of the best ceremonies of late was the opening of the Olympics, where Danny Boyle created a massive spectacle that communicated shared values in a non-religious way. It was big-budget joy. Most of us don't have such a budget but there has to be some nuance here. We may not have God. We may find the fuzziness of new age thinking with its emphasis on "nature" and "spirit" impure, but to dismiss the human need to express transcendence and connection with others as stupid is itself stupid.

Our ceremony had flowers and fires and Dylan, a Baptist minister and the Jabberwocky, half-Mexican siblings and symbols, a Catholic grandparent reading her prayer, a Muslim godparent and kids off their heads on helium at the party. A right old mishmash, then, but our mishmash.

In saying this I realise I am not a good atheist. Rather like mothering, perhaps I can only be a good enough one. But to move many away from religion, a viable atheism has to weave itself into the social fabric and shed this image of dour grumpiness. What can be richer than the celebration of our common humanity? Here is magic, colour, poetry. Life.

No comments:

Post a Comment