By querying the the absolute autonomy of the marketplace, Pope Francis is hardly making a radical critique. But such 'red scares' have long history

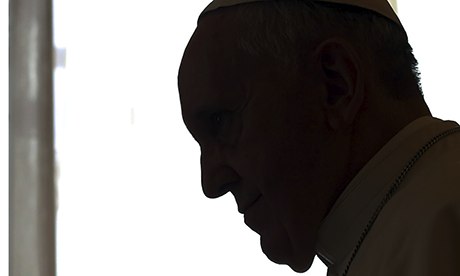

Pope Francis has been denounced as a Marxist by rightwingers for criticising 'unfettered capitalism'. Photograph: Alessandra Benedetti/Corbis

Some of his best friends are Marxists, Pope Francis announced last week. Well, not quite, but he has insisted that he knows some "Marxists who are good people". While making it clear that "Marxist ideology is wrong", the pontiff claimed he wasn't offended by being denounced as a Marxist by the US shock-jock, Rush Limbaugh. The conservative radio host and other rabid free-market ideologues have taken umbrage at the recent "apostolic exhortation" which criticised "unfettered capitalism" and the "globalisation of indifference" it has created.

The use of "Marxist" as a slur – along with kindred terms such as "socialist" and "communist" – is not a uniquely American phenomenon but is most familiar to us from the era of the infamous House Un-American Activities Committee, established in 1938 and, later, Joseph McCarthy's committee.

In that context, and during the "red scares" which followed it during the cold war, these were appellations used to identify and punish any criticism of capitalism, however sympathetic or merely reformist. Indeed, any dissent from mainstream dogma was "un-American".

America's first "red scare" took place in the wake of the 1918 Bolshevik revolution. To be a dissident from capitalism in any degree was to be a socialist or a "commie" and, therefore, "anti-American": the net of denunciation was cast wide enough to include immigrants, conscientious objectors, blacks and Jews.

American public culture is saturated with stories of "commie plots" and conspiracies and many, like the Hollywood Ten, the playwright Lillian Hellman, the actor Paul Robeson, and the writer Richard Wright were famously blacklisted for alleged communist connections. Even Martin Luther King has been accused of Marxism, as has John Kerry and, more recently, President Barack Obama was denounced as a "socialist" for bringing less well-off Americans into the ambit of corporate, very much capitalist, healthcare provision.

In Britain, while many Victorian liberals and radicals were careful to distance themselves from socialism, engagement with both Marxism and socialism has been historically less hostile than in the US. Nevertheless, the use of Marxist as an insult also indicating a treasonous lack of patriotism has been stepped up in recent years, featuring most prominently in the attacks on Ralph Miliband as "the man who hated Britain".

It is no accident that such terms are deliberately deployed as pejoratives at a time when an unregulated, rampant capitalism and its ideologues are in the dominant position but also fear growing unpopularity and subsequent challenge. In this context, "Marxism" refers not merely to thinking influenced by Karl Marx's magisterial three volumes laying bare the unavoidable exploitation at the heart of capitalism – it becomes a random, ill-conceived slur to stave off any and all criticism of its operations.

For a mainstream and still fundamentally conservative figure, Pope Francis has indeed gone further than many by poking the sacred cow that is trickle-down economics and querying "the absolute autonomy of the marketplace". These are not radical critiques of capitalism and have been made before by many, including Keynesian economists who would not consider themselves at all anti-capitalist but are more concerned with saving the system from its own ravages.

While Francis now appears to boldly advocate a church that is poor and "for the poor", he isn't about to tear up the Vatican's vast investment portfolio. We can welcoming the opening that his exhortation has provided for a discussion of the economic regime under which we labour and from which a few profit much more than others. Yet, it is also important to recognise that such criticism is of the sort which ultimately seeks to inoculate capitalism from disastrous meltdown by feeding it measured doses of healthy caution.

Perhaps it is time to properly revisit Marx's own insights into the workings of capitalism and ask how these remain relevant to understanding how the global economy functions. The pope's denunciation of the way in which "human beings are themselves considered consumer goods" was much more thoroughly anticipated in Marx's brilliant analysis of the commodity form which saw this process as central to capitalism, not merely an unhappy side effect of poor regulation.

"Exclusion" and "inequality" are similarly not happenstance spin-offs from a "new tyranny"; they are fundamental to a now old economic dynamic which seeks to concentrate the wealth in a few palms by extracting the labour from many hands. Of course capitalism is rife with "moral corruption", but we would also do well to look at how inequality is central to its very material workings.

There can be no moral regeneration that is not also a complete rejection of capitalism's essential immorality. It is futile to keep talking of "including the poor" within the ambit of capitalist opportunity: any good capitalist like our chancellor, George Osborne, understands very well that inequality and impoverishment (codename "austerity") is absolutely central to the creation and concentration of wealth. Anything less is simply to further the politics of illusion.