'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label slave. Show all posts

Showing posts with label slave. Show all posts

Sunday, 1 January 2023

Tuesday, 22 November 2022

Hypocrisy's Penalty Corner

Jawed Naqvi in The Dawn

THERE’S been severe criticism, primarily in the Western media, of the gross exploitation of migrant workers in Qatar’s bid to host football’s World Cup that began in Doha last week. There’s more than a grain of truth in the accusation, and there’s dollops of hypocrisy about it.

FIFA President Gianni Infantino brought it out nicely by calling out the Western media’s double standards in what is tantamount to shedding crocodile tears for the exploited workers.

The CNN, unsurprisingly, slammed Infantino’s anger, and quoted human rights groups as describing his comments as “crass” and an “insult” to migrant workers. Why is Infantino convinced that the Western media wallows in its own arrogance?

It is nobody’s secret that migrant workers in the Gulf are paid a pittance, which becomes more deplorable when compared to the enormous riches they help produce. As is evident, the workers’ exploitation is not specific to Qatar’s hosting of a football tournament, but a deeper malaise in which Western greed mocks its moral sermons.

As their earnings with hard labour abroad fetch them more than what they would get at home, the workers become unwitting partners in their own abuse. This has been the unwritten law around the generation of wealth in oil-rich Gulf countries, though their rulers are not alone in the exploitative venture.

Western colluders, nearly all of them champions of human rights, have used the oil extracted with cheap labour that plies Gulf economies, to control the world order. The West and the Gulf states have both benefited directly from dirt cheap workforce sourced from countries like India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the far away Philippines.

Making it considerably worse is the sullen cutthroat competition that has prevailed for decades between workers of different countries, thereby undercutting each other’s bargaining power. The bruising competition is not unknown to their respective governments that benefit enormously from the remittances from an exploited workforce. The disregard for work conditions is not only related to the Gulf workers, of course, but also migrant labour at home. In the case of India, we witnessed the criminal apathy they experienced in the Covid-19 emergency.

Asian women workers in the Gulf face quantifiably worse conditions. An added challenge they face is of sexual exploitation. Cheap labour imported from South Asia, therefore, answers to the overused though still germane term — Western imperialism. Infantino was spot on. Pity the self-absorbed Western press booed him down.

Sham outrage over a Gulf country hosting the World Cup is just one aspect of hypocrisy. A larger problem remains rooted in an undiscussed bias.

Moscow and Beijing in particular have been the Western media’s leading quarries from time immemorial. The boycott of the Moscow Olympics over the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan was dressed up as a moral proposition, which it might have been but for the forked tongue at play. That numerous Olympic contests went ahead undeterred in Western cities despite their illegal wars or support for dictators everywhere was never called out. What the West did with China, however, bordered on distilled criminality.

I was visiting Beijing in September 1993 with prime minister Narasimha Rao’s media team. The streets were lined with colourful buntings and slogans, which one mistook for a grand welcome for the visiting Indian leader. As it turned out the enthusiasm was all about Beijing’s bid to host the 2000 Olympics. It was fortunate Rao arrived on Sept 6 and could sign with Li Peng a landmark agreement for “peace and tranquility” on the Sino-Indian borders. Barely two week later, China would collapse into collective depression after Sydney snatched the 2000 Olympics from Beijing’s clasp. Western perfidy was at work again.

As it happened, other than Sydney and Beijing three other cities were also in the running — Manchester, Berlin and Istanbul — but, as The New York Times noted: “No country placed its prestige more on the line than China.” When the count began, China led the field with a clear margin over Sydney. Then the familiar mischief came into play.

Beijing led after each of the first three rounds, but was unable to win the required majority of the 89 voting members. One voter did not cast a ballot in the final two rounds. After the third round, in which Manchester won 11 votes, Beijing still led Sydney by 40 to 37 ballots. “But, confirming predictions that many Western delegates were eager to block Beijing’s bid, eight of Manchester’s votes went to Sydney and only three to the Chinese capital,” NYT reported. Human rights was cited as the cause. Hypocritically, that concern disappeared out of sight and Beijing hosted a grand Summer Olympics in 2008.

Football is a mesmerising game to watch. Its movements are comparable to musical notes of a riveting symphony. Above all, it’s a sport that cannot be easily fudged with. But its backstage in our era of the lucre stinks of pervasive corruption.

Anger in Beijing burst into the open when it was revealed in January 1999 that Australia’s Olympic Committee president John Coates promised two International Olympic Committee members $35,000 each for their national Olympic committees the night before the vote, which gave the games to Sydney by 45 votes to 43.

The Daily Mail described the “usual equanimity” with which Juan Antonio Samaranch, the then Spanish IOC president, tried to diminish the scam. The allegations against nine of the 10 IOC members accused of graft “have scant foundation and the remaining one has hardly done anything wrong”.

“In a speech to his countrymen,” recalled the Mail, “he blamed the press for ‘overreacting’ to the underhand tactics, including the hire of prostitutes, employed by Salt Lake City to host the next Winter Olympics.” Samaranch sidestepped any reference to the tactics employed by Sydney to stage the Millennium Summer Games.

This reality should never be obscured by other outrages, including the abominable working conditions of Asian workers in Qatar.

THERE’S been severe criticism, primarily in the Western media, of the gross exploitation of migrant workers in Qatar’s bid to host football’s World Cup that began in Doha last week. There’s more than a grain of truth in the accusation, and there’s dollops of hypocrisy about it.

FIFA President Gianni Infantino brought it out nicely by calling out the Western media’s double standards in what is tantamount to shedding crocodile tears for the exploited workers.

The CNN, unsurprisingly, slammed Infantino’s anger, and quoted human rights groups as describing his comments as “crass” and an “insult” to migrant workers. Why is Infantino convinced that the Western media wallows in its own arrogance?

It is nobody’s secret that migrant workers in the Gulf are paid a pittance, which becomes more deplorable when compared to the enormous riches they help produce. As is evident, the workers’ exploitation is not specific to Qatar’s hosting of a football tournament, but a deeper malaise in which Western greed mocks its moral sermons.

As their earnings with hard labour abroad fetch them more than what they would get at home, the workers become unwitting partners in their own abuse. This has been the unwritten law around the generation of wealth in oil-rich Gulf countries, though their rulers are not alone in the exploitative venture.

Western colluders, nearly all of them champions of human rights, have used the oil extracted with cheap labour that plies Gulf economies, to control the world order. The West and the Gulf states have both benefited directly from dirt cheap workforce sourced from countries like India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the far away Philippines.

Making it considerably worse is the sullen cutthroat competition that has prevailed for decades between workers of different countries, thereby undercutting each other’s bargaining power. The bruising competition is not unknown to their respective governments that benefit enormously from the remittances from an exploited workforce. The disregard for work conditions is not only related to the Gulf workers, of course, but also migrant labour at home. In the case of India, we witnessed the criminal apathy they experienced in the Covid-19 emergency.

Asian women workers in the Gulf face quantifiably worse conditions. An added challenge they face is of sexual exploitation. Cheap labour imported from South Asia, therefore, answers to the overused though still germane term — Western imperialism. Infantino was spot on. Pity the self-absorbed Western press booed him down.

Sham outrage over a Gulf country hosting the World Cup is just one aspect of hypocrisy. A larger problem remains rooted in an undiscussed bias.

Moscow and Beijing in particular have been the Western media’s leading quarries from time immemorial. The boycott of the Moscow Olympics over the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan was dressed up as a moral proposition, which it might have been but for the forked tongue at play. That numerous Olympic contests went ahead undeterred in Western cities despite their illegal wars or support for dictators everywhere was never called out. What the West did with China, however, bordered on distilled criminality.

I was visiting Beijing in September 1993 with prime minister Narasimha Rao’s media team. The streets were lined with colourful buntings and slogans, which one mistook for a grand welcome for the visiting Indian leader. As it turned out the enthusiasm was all about Beijing’s bid to host the 2000 Olympics. It was fortunate Rao arrived on Sept 6 and could sign with Li Peng a landmark agreement for “peace and tranquility” on the Sino-Indian borders. Barely two week later, China would collapse into collective depression after Sydney snatched the 2000 Olympics from Beijing’s clasp. Western perfidy was at work again.

As it happened, other than Sydney and Beijing three other cities were also in the running — Manchester, Berlin and Istanbul — but, as The New York Times noted: “No country placed its prestige more on the line than China.” When the count began, China led the field with a clear margin over Sydney. Then the familiar mischief came into play.

Beijing led after each of the first three rounds, but was unable to win the required majority of the 89 voting members. One voter did not cast a ballot in the final two rounds. After the third round, in which Manchester won 11 votes, Beijing still led Sydney by 40 to 37 ballots. “But, confirming predictions that many Western delegates were eager to block Beijing’s bid, eight of Manchester’s votes went to Sydney and only three to the Chinese capital,” NYT reported. Human rights was cited as the cause. Hypocritically, that concern disappeared out of sight and Beijing hosted a grand Summer Olympics in 2008.

Football is a mesmerising game to watch. Its movements are comparable to musical notes of a riveting symphony. Above all, it’s a sport that cannot be easily fudged with. But its backstage in our era of the lucre stinks of pervasive corruption.

Anger in Beijing burst into the open when it was revealed in January 1999 that Australia’s Olympic Committee president John Coates promised two International Olympic Committee members $35,000 each for their national Olympic committees the night before the vote, which gave the games to Sydney by 45 votes to 43.

The Daily Mail described the “usual equanimity” with which Juan Antonio Samaranch, the then Spanish IOC president, tried to diminish the scam. The allegations against nine of the 10 IOC members accused of graft “have scant foundation and the remaining one has hardly done anything wrong”.

“In a speech to his countrymen,” recalled the Mail, “he blamed the press for ‘overreacting’ to the underhand tactics, including the hire of prostitutes, employed by Salt Lake City to host the next Winter Olympics.” Samaranch sidestepped any reference to the tactics employed by Sydney to stage the Millennium Summer Games.

This reality should never be obscured by other outrages, including the abominable working conditions of Asian workers in Qatar.

Monday, 14 February 2022

Thursday, 27 May 2021

Tuesday, 18 May 2021

Thursday, 18 June 2020

Lying about our history? Now that's something Britain excels at

Protesters may be toppling statues, but millions of records about the end of empire and the slave trade were destroyed by the state by Ian Cobain in The Guardian

Members of the Devon Regiment assisting police in searching homes for Mau Mau rebels, Karoibangi, Kenya, circa 1954. Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty Images

It was inevitable that some would insist that ripping the statue of slave trader Edward Colston from its plinth and disposing of it in a harbour in Bristol was an act of historical revisionism; that others would argue that its removal was long overdue, and that the act itself was history in the making. After more statues were removed across the United States and Europe, Boris Johnson weighed in, arguing that “to tear [these statues] down would be to lie about our history”.

But lying about our history – and particularly about our late-colonial history – has been a habit of the British state for decades.

In 2013 I discovered that the Foreign and Commonwealth Office had been unlawfully concealing 1.2m historical files at a highly secure government compound at Hanslope Park, north of London.

Those files contained millions upon millions of pages of records stretching back to 1662, spanning the slave trade, the Boer wars, two world wars, the cold war and the UK’s entry into the European Common Market. More than 20,000 files concerned the withdrawal from empire.

There were so many of them that they took up 15 miles of floor-to-ceiling shelving at a specially built repository that a Foreign Office minister had opened in a private ceremony in 1992. Their retention was in breach of the Public Records Acts, and they had effectively been held beyond the reach of the Freedom of Information Act.

The FCO was not alone: at two warehouses in the English midlands, the UK’s Ministry of Defence was at the same time unlawfully hoarding 66,000 historical files, including many about the conflict in Northern Ireland.

When the files concerned with the withdrawal from empire began to be transferred to the UK’s National Archives – where they should have been for years, and where historians and members of the public could finally examine them – it became clear that enormous amounts of documentation had been destroyed during the process of decolonisation.

Helpfully perhaps, colonial officials had completed “destruction certificates”, in which they declared that they had disposed of sensitive papers, and many of these certificates had survived within the secret archive.

Beginning in India in 1947, government officials had incinerated material that would in any way embarrass Her Majesty’s government, her armed forces, or her colonial civil servants. At the end of that year, an Observer correspondent noted large palls of smoke appearing over government offices in Jerusalem.

As decolonisation gathered pace, British officials developed a series of parallel file registries in the colonies: one that was to be handed over to post-independence governments, and one that contained papers that were to be steadily destroyed or flown back to London.

As a consequence, newly independent governments found themselves attempting to administer their territories on the basis of an incomplete record of what had happened before.

In Uganda in March 1961, colonial officials gave this process a new name: Operation Legacy. Before long the term spread to neighbouring colonies, where only “British subjects of European descent” were to be involved in the weeding and destruction of documents, a process that was overseen by police special branch officers. A new security classification, the “W” or “Watch series”, was introduced, and sensitive papers were stamped with a red letter W.

Subsequently, there was the “Guard series” of papers stamped with a letter “G”. These could be shared with officials from Australia, Canada, South Africa and New Zealand, but whenever this happened “the information should be accompanied by an oral warning that it must not be communicated to the Americans”. The Americans, it seems to have been assumed, were likely to be less forgiving of the sins of empire.

In May that year the colonial secretary, Iain Macleod, issued instructions that the documents to be destroyed or smuggled back to London should include anything that might embarrass HMG; embarrass her military, police or public servants; that might compromise sources of intelligence; or which could be used “unethically” by post-independence governments.

By “unethically”, Macleod appears to mean that he did not wish to see the governments of newly independent nations expose, or threaten to expose, some of the more challenging aspects of the end of empire. There was certainly plenty to hide: the torture and murder of rebels in Kenya; the brutal suppression of insurgencies in Cyprus and later Aden; massacres in Malaya; the toppling of a democratically elected government in British Guiana.

Instructions were also issued on the means by which papers should be destroyed: when they were burned, “the waste should be reduced to ash and the ashes broken up”. In Kenya, officials were informed that “it is permissible, as an alternative to destruction by fire, for documents to packed in weighed crates and dumped in very deep and current-free waters at maximum practicable distance from the coast”.

Operation Legacy was, as one colonial official admitted, “an orgy of destruction”, and it was carried out across the globe between the late 1940s and the early 70s.

The operation – and its attempts to conceal and manipulate history in an attempt to sculpt an official narrative – speaks of a certain jitteriness on the part of the British state, as if it feared that interpretations of the past that were based upon its own records would find it difficult to celebrate the “greatness” of British history.

It seems likely that uncertainty about the imperial mission also played a part in the commissioning of Colston’s statue. It was erected in 1895, a full 174 years after his death, at a time when the British were anxious about their rapidly expanded empire. The first Boer war had ended badly for them, exposing the physical weakness of soldiers recruited from urban slums; the United States was emerging as an industrial force; and Germany appeared to be challenging the Royal Navy’s maritime dominance.

The answer, it seems, was the erection of statues, up and down the United Kingdom, of early “heroes” of empire – even slave traders – as an inspiring example to the adventurers and imperialists to come.

Now that’s an act of act of historical revisionism.

It was inevitable that some would insist that ripping the statue of slave trader Edward Colston from its plinth and disposing of it in a harbour in Bristol was an act of historical revisionism; that others would argue that its removal was long overdue, and that the act itself was history in the making. After more statues were removed across the United States and Europe, Boris Johnson weighed in, arguing that “to tear [these statues] down would be to lie about our history”.

But lying about our history – and particularly about our late-colonial history – has been a habit of the British state for decades.

In 2013 I discovered that the Foreign and Commonwealth Office had been unlawfully concealing 1.2m historical files at a highly secure government compound at Hanslope Park, north of London.

Those files contained millions upon millions of pages of records stretching back to 1662, spanning the slave trade, the Boer wars, two world wars, the cold war and the UK’s entry into the European Common Market. More than 20,000 files concerned the withdrawal from empire.

There were so many of them that they took up 15 miles of floor-to-ceiling shelving at a specially built repository that a Foreign Office minister had opened in a private ceremony in 1992. Their retention was in breach of the Public Records Acts, and they had effectively been held beyond the reach of the Freedom of Information Act.

The FCO was not alone: at two warehouses in the English midlands, the UK’s Ministry of Defence was at the same time unlawfully hoarding 66,000 historical files, including many about the conflict in Northern Ireland.

When the files concerned with the withdrawal from empire began to be transferred to the UK’s National Archives – where they should have been for years, and where historians and members of the public could finally examine them – it became clear that enormous amounts of documentation had been destroyed during the process of decolonisation.

Helpfully perhaps, colonial officials had completed “destruction certificates”, in which they declared that they had disposed of sensitive papers, and many of these certificates had survived within the secret archive.

Beginning in India in 1947, government officials had incinerated material that would in any way embarrass Her Majesty’s government, her armed forces, or her colonial civil servants. At the end of that year, an Observer correspondent noted large palls of smoke appearing over government offices in Jerusalem.

As decolonisation gathered pace, British officials developed a series of parallel file registries in the colonies: one that was to be handed over to post-independence governments, and one that contained papers that were to be steadily destroyed or flown back to London.

As a consequence, newly independent governments found themselves attempting to administer their territories on the basis of an incomplete record of what had happened before.

In Uganda in March 1961, colonial officials gave this process a new name: Operation Legacy. Before long the term spread to neighbouring colonies, where only “British subjects of European descent” were to be involved in the weeding and destruction of documents, a process that was overseen by police special branch officers. A new security classification, the “W” or “Watch series”, was introduced, and sensitive papers were stamped with a red letter W.

Subsequently, there was the “Guard series” of papers stamped with a letter “G”. These could be shared with officials from Australia, Canada, South Africa and New Zealand, but whenever this happened “the information should be accompanied by an oral warning that it must not be communicated to the Americans”. The Americans, it seems to have been assumed, were likely to be less forgiving of the sins of empire.

In May that year the colonial secretary, Iain Macleod, issued instructions that the documents to be destroyed or smuggled back to London should include anything that might embarrass HMG; embarrass her military, police or public servants; that might compromise sources of intelligence; or which could be used “unethically” by post-independence governments.

By “unethically”, Macleod appears to mean that he did not wish to see the governments of newly independent nations expose, or threaten to expose, some of the more challenging aspects of the end of empire. There was certainly plenty to hide: the torture and murder of rebels in Kenya; the brutal suppression of insurgencies in Cyprus and later Aden; massacres in Malaya; the toppling of a democratically elected government in British Guiana.

Instructions were also issued on the means by which papers should be destroyed: when they were burned, “the waste should be reduced to ash and the ashes broken up”. In Kenya, officials were informed that “it is permissible, as an alternative to destruction by fire, for documents to packed in weighed crates and dumped in very deep and current-free waters at maximum practicable distance from the coast”.

Operation Legacy was, as one colonial official admitted, “an orgy of destruction”, and it was carried out across the globe between the late 1940s and the early 70s.

The operation – and its attempts to conceal and manipulate history in an attempt to sculpt an official narrative – speaks of a certain jitteriness on the part of the British state, as if it feared that interpretations of the past that were based upon its own records would find it difficult to celebrate the “greatness” of British history.

It seems likely that uncertainty about the imperial mission also played a part in the commissioning of Colston’s statue. It was erected in 1895, a full 174 years after his death, at a time when the British were anxious about their rapidly expanded empire. The first Boer war had ended badly for them, exposing the physical weakness of soldiers recruited from urban slums; the United States was emerging as an industrial force; and Germany appeared to be challenging the Royal Navy’s maritime dominance.

The answer, it seems, was the erection of statues, up and down the United Kingdom, of early “heroes” of empire – even slave traders – as an inspiring example to the adventurers and imperialists to come.

Now that’s an act of act of historical revisionism.

Sunday, 7 June 2020

Britain is not America. But we too are disfigured by deep and pervasive racism

Yes, it would be foolish to see only parallels in the US and UK experience. But to downplay our own problems would be shameful writes David Olusoga in The Guardian

FacebookTwitterPinterest The British actor John Boyega speaks to the crowd during a Black Lives Matter protest in Hyde Park on 3 June 2020 in London, England. Photograph: Justin Setterfield/Getty Images

Yet in the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s death there was little reason to imagine anything would be any different this time around. For African Americans, one of the most appalling aspects of Floyd’s murder was that they had seen it all before. The same story with the same outcome, all that changed was the name of the victim – Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Walter Scott.

For many black Britons, Floyd’s death stirred memories of another list of names, those of the members of their community killed or rendered disabled in similar circumstances at the hands of the British police or immigration officers. On Tuesday, the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, south London – the closest thing we have in this country to a museum to the black British experience – tweeted the names and the photographs of some of them – Mark Duggan, Sheku Bayoh, Sean Rigg, Sarah Reed, Cherry Groce, Leon Briggs, Christopher Alder, Brian Douglas.

Yet almost instantly a predictable chorus of voices, emanating from predictable corners of British public life, rose up to dismiss the whole thing as an irrelevance. Using a familiar playbook, they accused those black Britons who see reflections of their own situation in the experiences of African Americans of making false comparisons.

The US situation is unique in both its depth and ferocity, they say, so that no parallels can be drawn with the situation in Britain. The smoke-and-mirrors aspect of this argument is that it attempts to focus attention solely on police violence, rather than the racism that inspired it. Those who make it usually point to the ubiquity of firearms in US law enforcement, as proof that the US reality is beyond meaningful comparison. But firearms had nothing to do with the killing of George Floyd. Neither were they a factor in the death of Freddie Gray or the sidewalk killing of Eric Garner, who, like Floyd, pleaded for his life, saying 11 times to the officers who pinned him down: “I can’t breathe”, the same words Floyd used in his final moments. Nor were guns involved in many of the cases when black people have died in custody or during arrest in Britain.

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history

When black Britons draw parallels between their experiences and those of African Americans, they are not suggesting that those experiences are identical. Few people would deny that in many respects life is better for non-white people in the UK than in the US. The problem is that it is not as “better” as some like to believe. Black men are stopped and searched at nine times the rate of white men. Black people make up 3% of the population of England and Wales but account for 12% of the prison population and not since 1971 have British police officers been prosecuted for the killing of a black man, and even then they were charged with the lesser crime of manslaughter and that charge was later dropped.

To say that the racism that infects parts of our police force and criminal justice system is less virulent than that which poisons the lives of 40 million African Americans is not much of a boast. Is that really the extent of our ambition – to be a somewhat less racist nation than one led by a man who describes white nationalists and members of the Ku Klux Klan as “very fine people”? Surely we who dwell in what the actor Laurence Fox recently assured us is “the most tolerant, lovely country in Europe” have higher hopes?

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history. It began in 1807, with the abolition of the slave trade and picked up steam three decades later with the end of British slavery, twin events that marked the beginning of 200 years of moral posturing and historical amnesia. The Victorian readers who rightly wept over Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, conveniently forgot which nation had carried his ancestors into slavery and didn’t dwell on the fact that most of the cotton produced by American slaves like him was shipped to Liverpool.

For two centuries, we have deployed American racism as a distraction. It’s as if we find it easier to recognise American forms of racism than we do our own home-grown varieties. Convenient, as pointing fingers is always more comforting than looking in the mirror.

Demonstrator at a Black Lives Matter protest on 6 June 2020 in Cardiff. Photograph: Matthew Horwood/Getty Images

One of the more pertinent statements made during this past extraordinary week appeared in one of the last places I would have thought to look – in the pages of Vogue, not a publication I instinctively turn to at a moment of profound political tension.

“Racism is a global issue. Racism is a British issue. It is not one that is merely confined to the United States – it is everywhere, and it is systemic,” wrote Edward Enninful, the editor-in-chief of the magazine’s British edition. The ubiquity of racism has been brought to stark and sudden attention by the killing of George Floyd and by the unprecedented wave of protests, demonstrations and rioting that followed.

Filmed by many witnesses and now viewed millions of times, the killing of Floyd by a Minnesota policeman, a 21st-century lynching, is so sickening a crime that the revulsion it has induced has become a global phenomenon.

The demonstrators and activists who have taken to the streets have, however, been motivated by more than revulsion. They have also been stirred to action by acknowledging a fundamental truth – that the killing of Floyd has to be understood as a symptom of systemic racism. By building their campaign around that reality they have promoted radical and challenging conversations – in countries on both sides of the Atlantic – about the nature of racism and the actions that people of all races can take in eliminating it. These are conversations that we have needed for a very long time.

Led by young people, many of them inspired by Black Lives Matter, and involving people of all ethnicities, the protests have morphed into a worldwide anti-racist movement. No longer is this moment solely about police violence nor is it limited to America. Both online and on the streets it is calling out racism, wherever it exists and in whatever forms it is found. In both the US and in Europe, people are asking, tentatively, if this might be a defining moment of change.

One of the more pertinent statements made during this past extraordinary week appeared in one of the last places I would have thought to look – in the pages of Vogue, not a publication I instinctively turn to at a moment of profound political tension.

“Racism is a global issue. Racism is a British issue. It is not one that is merely confined to the United States – it is everywhere, and it is systemic,” wrote Edward Enninful, the editor-in-chief of the magazine’s British edition. The ubiquity of racism has been brought to stark and sudden attention by the killing of George Floyd and by the unprecedented wave of protests, demonstrations and rioting that followed.

Filmed by many witnesses and now viewed millions of times, the killing of Floyd by a Minnesota policeman, a 21st-century lynching, is so sickening a crime that the revulsion it has induced has become a global phenomenon.

The demonstrators and activists who have taken to the streets have, however, been motivated by more than revulsion. They have also been stirred to action by acknowledging a fundamental truth – that the killing of Floyd has to be understood as a symptom of systemic racism. By building their campaign around that reality they have promoted radical and challenging conversations – in countries on both sides of the Atlantic – about the nature of racism and the actions that people of all races can take in eliminating it. These are conversations that we have needed for a very long time.

Led by young people, many of them inspired by Black Lives Matter, and involving people of all ethnicities, the protests have morphed into a worldwide anti-racist movement. No longer is this moment solely about police violence nor is it limited to America. Both online and on the streets it is calling out racism, wherever it exists and in whatever forms it is found. In both the US and in Europe, people are asking, tentatively, if this might be a defining moment of change.

FacebookTwitterPinterest The British actor John Boyega speaks to the crowd during a Black Lives Matter protest in Hyde Park on 3 June 2020 in London, England. Photograph: Justin Setterfield/Getty Images

Yet in the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s death there was little reason to imagine anything would be any different this time around. For African Americans, one of the most appalling aspects of Floyd’s murder was that they had seen it all before. The same story with the same outcome, all that changed was the name of the victim – Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Walter Scott.

For many black Britons, Floyd’s death stirred memories of another list of names, those of the members of their community killed or rendered disabled in similar circumstances at the hands of the British police or immigration officers. On Tuesday, the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, south London – the closest thing we have in this country to a museum to the black British experience – tweeted the names and the photographs of some of them – Mark Duggan, Sheku Bayoh, Sean Rigg, Sarah Reed, Cherry Groce, Leon Briggs, Christopher Alder, Brian Douglas.

Yet almost instantly a predictable chorus of voices, emanating from predictable corners of British public life, rose up to dismiss the whole thing as an irrelevance. Using a familiar playbook, they accused those black Britons who see reflections of their own situation in the experiences of African Americans of making false comparisons.

The US situation is unique in both its depth and ferocity, they say, so that no parallels can be drawn with the situation in Britain. The smoke-and-mirrors aspect of this argument is that it attempts to focus attention solely on police violence, rather than the racism that inspired it. Those who make it usually point to the ubiquity of firearms in US law enforcement, as proof that the US reality is beyond meaningful comparison. But firearms had nothing to do with the killing of George Floyd. Neither were they a factor in the death of Freddie Gray or the sidewalk killing of Eric Garner, who, like Floyd, pleaded for his life, saying 11 times to the officers who pinned him down: “I can’t breathe”, the same words Floyd used in his final moments. Nor were guns involved in many of the cases when black people have died in custody or during arrest in Britain.

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history

When black Britons draw parallels between their experiences and those of African Americans, they are not suggesting that those experiences are identical. Few people would deny that in many respects life is better for non-white people in the UK than in the US. The problem is that it is not as “better” as some like to believe. Black men are stopped and searched at nine times the rate of white men. Black people make up 3% of the population of England and Wales but account for 12% of the prison population and not since 1971 have British police officers been prosecuted for the killing of a black man, and even then they were charged with the lesser crime of manslaughter and that charge was later dropped.

To say that the racism that infects parts of our police force and criminal justice system is less virulent than that which poisons the lives of 40 million African Americans is not much of a boast. Is that really the extent of our ambition – to be a somewhat less racist nation than one led by a man who describes white nationalists and members of the Ku Klux Klan as “very fine people”? Surely we who dwell in what the actor Laurence Fox recently assured us is “the most tolerant, lovely country in Europe” have higher hopes?

Excusing or downplaying British racism with comparisons to the US is a bad habit with a long history. It began in 1807, with the abolition of the slave trade and picked up steam three decades later with the end of British slavery, twin events that marked the beginning of 200 years of moral posturing and historical amnesia. The Victorian readers who rightly wept over Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, conveniently forgot which nation had carried his ancestors into slavery and didn’t dwell on the fact that most of the cotton produced by American slaves like him was shipped to Liverpool.

For two centuries, we have deployed American racism as a distraction. It’s as if we find it easier to recognise American forms of racism than we do our own home-grown varieties. Convenient, as pointing fingers is always more comforting than looking in the mirror.

Saturday, 22 April 2017

How to overcome the Master Slave Dialectic in Capitalism

Prof. Wolff on Hegel's Master-Slave Dialectic

Friday, 19 February 2016

Forgotten heroes – the true story of India

In his history of the people who helped make India today, Sunil Khilnani (The Guardian) set out to complicate western stereotypes. He ended up also challenging the prejudices and stories Indians tell themselves about their past

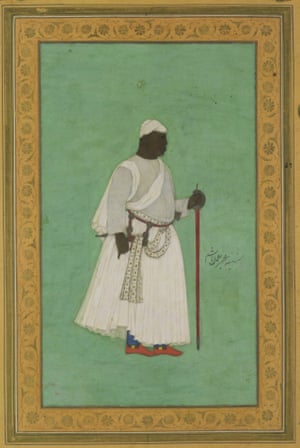

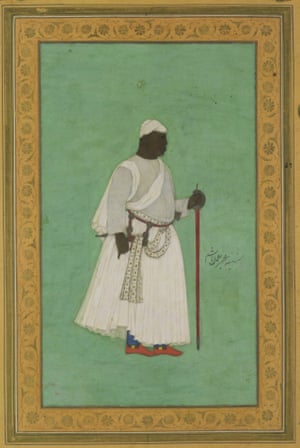

The rise and historical eclipse of the most powerful African in Indian history, Malik Ambar (1548-1626), is just one of the effacements and distortions I explored in Incarnations. I intended my book to complicate reigning western stereotypes – of India as a land of mystical but not intellectual traditions; of the Indian agrarian poor as meek and passive; of a culture and an economy only recently woken up to globalisation. But I wanted to wrestle as well with how Indians’ own prejudices and stereotypes – regarding race, faith, gender, caste and respect for individuality itself – contribute to the murky way Indian history gets told. Clarifying the story of Malik Ambar might be a good place to start.

***

We usually think of the African slave trade as running from east to west, but there was a thriving, little-remembered traffic that sailed eastwards to India, too. Indian rulers, particularly on Western India’s vast Deccan plain, acquired their human chattel from Arab traders in exchange for luxurious cloth. Kings and sultans, perpetually battling each other for territory and treasure, prized the African slaves as warriors. Thus in the mid-16th century, Malik Ambar was among the adolescent cargo offloaded on the Konkan coast.

Sold into slavery as a child by his impoverished parents, and converted by Muslim masters, the teenager arrived on the subcontinent having acquired an arsenal of non-martial skills – multiple languages, irrigation engineering, administration and accounting among them. As he passed through the hands of Deccan potentates, he became recognised not just as a soldier, but as a military and political strategist. Finally freed upon the death of a master whose power he had helped secure, he quickly amassed power of his own. Leading a mercenary army of crack horsemen that ultimately grew to a force of 50,000, he became a lethal accessory to Deccan rulers hoping to resist the expansionist aims of Mughal emperor Akbar and his son Jahangir. Through guerrilla tactics and night-time raids in the craggy, ravined landscape of the Deccan, Malik Ambar severed Mughal supply lines, stopped their southward thrust and gained control over large swaths of the region.

Malik Ambar

Emperor Jahangir, frustrated by his inability to defeat the powerful Ethiopian, actually took to commissioning gruesome miniature paintings in which he slayed his nemesis on paper. Jahangir might have been chuffed had he foreseen the future, which secured the elimination of Malik Ambar he so furiously sought. Malik Ambar wasn’t a Hindu native defending some ancient motherland. He was a dark-skinned, Muslim outsider, and thereby destined to be diminished. Descendents of African slaves now live poor and ghettoised, many of them in Gujarat, where I saw the legendary West Indian cricketers mocked as monkeys. And children growing up in those shunned communities will find no mention in their schoolbooks of a self-made power entrepreneur whose skin colour and lineage they share.

***

Both Indian and western approaches to the subcontinent’s past tend to ignore the experiences of individuals who don’t fit into grand narratives: stories (in India) of national uplift, religious unity or cultural cohesion, and (in the west) of a herd-like, prayerful and sometimes petulant nation just shaking off the hangover of colonisation. The misconstruals leave many people, inside and outside the country, with what is, at best gloss, a young-adult version of Indian history. To my mind, India’s real history is something like the Malik Ambar story writ large: unpredictable, eccentric, internationally connected and compelling fresh attention – not least for what it tells us about India now.

We have seen what happens when cultural biases run against a historical figure. So what if the biases run in the figure’s favour? That individual often gets turned into a demi-god, while the experiences of the actual, inconsistent human being fall away. As I chased down historical lives in far-flung communities, at archaeological sites, and in archives and texts, I sometimes noticed an almost comical gap between the superhero guises some figures are forced to wear today and their own self-critical sensibilities. One such was India’s first global guru, who brought yoga to the west: the baby-faced, proselytising monk known as Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902). Nowadays in India he is portrayed as the heroic personification of modern muscular Hinduism, a man insistent about the superiority of his religion over all others. (He is also a personal hero of Indian prime minister Narendra Modi.) Less well remembered is the Vivekananda who could be a perceptive critic of Hindu society.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Swami Vivekananda

Vivekananda’s fame derived from lectures on Hinduism that he delivered in flamboyant, saffron-robed style across America and Europe in the 1890s. But even as he took those audiences by storm (“I give them spirituality, and they give me money,” he wrote with a wink to one of his Indian patrons), he was deeply shaken by his first encounters with an egalitarianism and social progressiveness that his fellow Hindus lacked. Visiting a Massachusetts women’s penitentiary, he was astonished by the dignity even criminals were afforded. “Oh, how my heart ached to think of what we think of the poor, the low in India,” he wrote to a friend back home. “They have no chance, no escape, no way to climb up … They have forgotten that they too are men. And the result is slavery.”

The contradictions lacing Vivekananda’s speeches and letters – on whether caste was integral to Hinduism, on the validity of certain Hindu rituals and customs – intimate the depth of his intellectual struggle, and one of his greatest internal conflicts was with the effect of his faith on the powerless. “No religion on earth preaches the dignity of humanity in such a lofty strain as Hinduism,” he would write, “and no religion treads upon the necks of the poor and low in such a fashion as Hinduism.” But such contours in Vivekananda’s personality and intellectual life got flattened during his conversion into a laminated image: that of righteous Hindu nationalist avenger of the Muslim and colonial conquests of India, ambivalent about nothing at all.

***

In modern India, writers and historians have been intimidated – and libraries and bookshops ransacked – when they have dared to treat vaunted figures as historical beings. By insisting that favourites from India’s past be preserved in memory as godlike, full of certitude and above human consideration, we don’t just deny them their real natures, we sabotage their exemplary force.

Indian sexism being even more deeply rooted than racism, I can’t claim I was surprised to find that there were far fewer historical records for significant female lives than there were for their male counterparts. But what I saw more clearly is how an absence of documentary sources plays into our ridiculous cultural tendency to turn real women of intellect, judgment, fallibility and bravery into goddess-types

A procession held in 2015 to mark the anniversary of the birth of Bhim Rao Ambedkar in Mumbai, India. Photograph: Rafiq Maqbool/AP

And weren’t those minimally individuated Indians gentle and spiritual as they waited for their next karmic promotion? I was therefore delighted, visiting Mysore, to hold a tray bearing a palm leaf manuscript from around the turn of the Christian millennium that, when rediscovered a century ago, summarily exploded such cliches. The Arthashastra, a detailed treatise on statecraft and the art of government, gave counsel to kings that made Machiavelli’s look milquetoast (one gets a hint from the chapter titles, which feel as if they were written this year, perhaps by a parliamentary investigative committee: “Establishment of Clandestine Operatives”, “Pacifying a Territory Gained”, “Surveillance of People with Secret Income” and “Investigation through Interrogation and Torture”). The author was a man known as Kautilya, and, though all we have of him is this text, it gives a tantalising rebuttal to suggestions that ancient Indian interests were primarily spiritual.

As I worked, I was moved by how many of the 50 lives I studied posed pointed challenges to the Indian present

As does another work of analytic intellect, by the 5BCE master of the Sanskrit language, Panini. In what amounts to a mere 40 pages, he created the most complete linguistic system in history. This masterwork, known as The Ashtadhyayi, helped make Sanskrit the lingua franca of the Asian world for more than 1,000 years. Today, Panini’s system would be called a generative grammar, something modern linguistic philosophers such as Noam Chomsky and his students have been working for the past half century to develop. It is arguably from the Sanskrit tradition – whose logic Panini helped explain – that India’s present-day century software revolution emerged. And then there’s Ramanujan, the young mathematics prodigy whose century-old notebook scribblings are, as we speak, helping other scientists unravel the nature of the universe. Perhaps there’s something mystical there, in the postulates of quantum physics; though I don’t think it’s what the colonialists had in mind.

***

Other western misperceptions still present themselves on a daily basis – for instance, the notion that social conditions are uniformly dismal across India. Consider the unaddressed crimes and daily oppressions against Indian women, which have rightly provoked international outrage. Draw closer, and you will see that the outrage obscures telling differences between the opportunities for women in northern India and women in the more progressive south, where child marriage and fertility rates are far lower, and female literacy and work participation rates far higher. Some of that divergence has to do not with culture, but with reform-inspired historical crusades – including one led by a Tamil primary-school dropout known as Periyar (1879-1973).

He was an atheist and rationalist (beliefs that can get you killed in India today), and from the 1920s waged an intellectual campaign against the upper-caste northerners dominating the national movement. Setting himself up as the anti-Gandhi (wearing black, to counter Gandhi’s habit of dressing in white), he pressed for equal treatment of the lower castes, greater recognition of southern culture and language and, above all, greater freedoms for women in a country where wagons were still circled around the patriarchal family. For almost half a century, he advocated women’s rights and unhindered access to contraception. The further I delved into his story, and those of other social reformers, the more strongly I was reminded of how, under sustained pressure, even rigid societies can be changed.

***

Occasionally, walking through slum or village lanes to research Incarnations, I overheard teenagers cheerfully explaining to their friends what I was up to – it went along the lines of: “He’s telling the story of how India became number one.” Indeed, it is a habit of national histories to justify the present as the perfect and necessary outcome of what came before. But as I worked, I was moved by how many of the 50 lives I studied posed, like Malik Ambar’s life, pointed challenges to the Indian present.

Mahatma Gandhi with his two granddaughters in 1947. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

Through religious collisions, and philosophical and ethical explorations, those individuals were part of intense arguments that have kept going for millennia: about what kind of life is worth living, what kind of society is worth having, which hierarchies are morally legitimate, what role religion has in the political and legal order, what kind of love is valid, who owns the water and land, and what kind of place India should be. A civilisation able to produce a Buddha, a Mahavira, a Mirabai, a Birsa Munda, an Amrita Sher-Gil, a Muhammad Iqbal, an Ambedkar and a Gandhi is a place open both to radical experiments with self-definition and productive arguments about what a country and its people should value. That creative energy is worth recalling at a time when some in India seek to transform a ferment of ideas into a singular religious concoction.

Despite the current, cramped political climate, or maybe because of it, it seemed to me an essential moment to push for a deeper discussion of the Indian past – and not for the benefit of Indians alone. We are done now with the age in which what happened in India was considered peripheral to what used to be called the first world. Back then, those who wrote about the country had to make arguments for its relevance to, for instance, the larger story of democracy. Meanwhile, some of the most compelling minds from India’s past were forced to exist in splendid isolation, instead of being recognised for what they really were: figures engaged with other individuals and ideas across time, across borders. Today, India, in both its positive and negative aspects, is becoming central to discussions about the world at large. So it is time to reconsider not just the stories Indians like to tell themselves, but also the stories the world tells about us.

Bhutanatha Lake, Badami, India. Photograph: Chris Lisle/Corbis

Years ago, I scored a ticket to the first cricket Test match to be played in the city of Ahmedabad, Gujarat: India versus a West Indian 11 that included the peerless Viv Richards. I had expectations of an epic match as I joined other fans pushing into the brand new ground. But by the end, it was the performance of the spectators, not the players, that had staggered me. As the West Indians took the field, loud monkey-whoops filled the air, and banana skins rained down from the stands. The pelted players – probably the greatest West Indian team in history – stood there in their flannels, stunned.

Indians are rightly sensitive about racism directed at them; an Indian student beaten up in Australia, say, will swiftly become national news. Yet some Indians can be unthinkingly at ease with their own contempt for people of darker skin – a contradiction that warps both our present and our sense of the Indian past. As I travelled across India exploring the contemporary afterlives of 50 important historical figures spanning 2,500 years for Incarnations, my new book and 50-part BBC radio series, I heard dozens of young Indians extoll the bravery of Shivaji, the 17th-century Maratha warrior who defied the Mughals and serves today as a symbol of Hindu pride and resistance to Muslim rule. But when I mentioned a fierce resistor of Mughal expansion who came before Shivaji, young eyes went blank. For that forgotten leader doesn’t fall into any of the standard narrative silos of Indian history – Hindu, Muslim or European. Rather, he was an uncommonly clever and adaptive Ethiopian who had been shipped to India as a teenaged slave.

Years ago, I scored a ticket to the first cricket Test match to be played in the city of Ahmedabad, Gujarat: India versus a West Indian 11 that included the peerless Viv Richards. I had expectations of an epic match as I joined other fans pushing into the brand new ground. But by the end, it was the performance of the spectators, not the players, that had staggered me. As the West Indians took the field, loud monkey-whoops filled the air, and banana skins rained down from the stands. The pelted players – probably the greatest West Indian team in history – stood there in their flannels, stunned.

Indians are rightly sensitive about racism directed at them; an Indian student beaten up in Australia, say, will swiftly become national news. Yet some Indians can be unthinkingly at ease with their own contempt for people of darker skin – a contradiction that warps both our present and our sense of the Indian past. As I travelled across India exploring the contemporary afterlives of 50 important historical figures spanning 2,500 years for Incarnations, my new book and 50-part BBC radio series, I heard dozens of young Indians extoll the bravery of Shivaji, the 17th-century Maratha warrior who defied the Mughals and serves today as a symbol of Hindu pride and resistance to Muslim rule. But when I mentioned a fierce resistor of Mughal expansion who came before Shivaji, young eyes went blank. For that forgotten leader doesn’t fall into any of the standard narrative silos of Indian history – Hindu, Muslim or European. Rather, he was an uncommonly clever and adaptive Ethiopian who had been shipped to India as a teenaged slave.

The rise and historical eclipse of the most powerful African in Indian history, Malik Ambar (1548-1626), is just one of the effacements and distortions I explored in Incarnations. I intended my book to complicate reigning western stereotypes – of India as a land of mystical but not intellectual traditions; of the Indian agrarian poor as meek and passive; of a culture and an economy only recently woken up to globalisation. But I wanted to wrestle as well with how Indians’ own prejudices and stereotypes – regarding race, faith, gender, caste and respect for individuality itself – contribute to the murky way Indian history gets told. Clarifying the story of Malik Ambar might be a good place to start.

***

We usually think of the African slave trade as running from east to west, but there was a thriving, little-remembered traffic that sailed eastwards to India, too. Indian rulers, particularly on Western India’s vast Deccan plain, acquired their human chattel from Arab traders in exchange for luxurious cloth. Kings and sultans, perpetually battling each other for territory and treasure, prized the African slaves as warriors. Thus in the mid-16th century, Malik Ambar was among the adolescent cargo offloaded on the Konkan coast.

Sold into slavery as a child by his impoverished parents, and converted by Muslim masters, the teenager arrived on the subcontinent having acquired an arsenal of non-martial skills – multiple languages, irrigation engineering, administration and accounting among them. As he passed through the hands of Deccan potentates, he became recognised not just as a soldier, but as a military and political strategist. Finally freed upon the death of a master whose power he had helped secure, he quickly amassed power of his own. Leading a mercenary army of crack horsemen that ultimately grew to a force of 50,000, he became a lethal accessory to Deccan rulers hoping to resist the expansionist aims of Mughal emperor Akbar and his son Jahangir. Through guerrilla tactics and night-time raids in the craggy, ravined landscape of the Deccan, Malik Ambar severed Mughal supply lines, stopped their southward thrust and gained control over large swaths of the region.

Malik Ambar

Emperor Jahangir, frustrated by his inability to defeat the powerful Ethiopian, actually took to commissioning gruesome miniature paintings in which he slayed his nemesis on paper. Jahangir might have been chuffed had he foreseen the future, which secured the elimination of Malik Ambar he so furiously sought. Malik Ambar wasn’t a Hindu native defending some ancient motherland. He was a dark-skinned, Muslim outsider, and thereby destined to be diminished. Descendents of African slaves now live poor and ghettoised, many of them in Gujarat, where I saw the legendary West Indian cricketers mocked as monkeys. And children growing up in those shunned communities will find no mention in their schoolbooks of a self-made power entrepreneur whose skin colour and lineage they share.

***

Both Indian and western approaches to the subcontinent’s past tend to ignore the experiences of individuals who don’t fit into grand narratives: stories (in India) of national uplift, religious unity or cultural cohesion, and (in the west) of a herd-like, prayerful and sometimes petulant nation just shaking off the hangover of colonisation. The misconstruals leave many people, inside and outside the country, with what is, at best gloss, a young-adult version of Indian history. To my mind, India’s real history is something like the Malik Ambar story writ large: unpredictable, eccentric, internationally connected and compelling fresh attention – not least for what it tells us about India now.

We have seen what happens when cultural biases run against a historical figure. So what if the biases run in the figure’s favour? That individual often gets turned into a demi-god, while the experiences of the actual, inconsistent human being fall away. As I chased down historical lives in far-flung communities, at archaeological sites, and in archives and texts, I sometimes noticed an almost comical gap between the superhero guises some figures are forced to wear today and their own self-critical sensibilities. One such was India’s first global guru, who brought yoga to the west: the baby-faced, proselytising monk known as Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902). Nowadays in India he is portrayed as the heroic personification of modern muscular Hinduism, a man insistent about the superiority of his religion over all others. (He is also a personal hero of Indian prime minister Narendra Modi.) Less well remembered is the Vivekananda who could be a perceptive critic of Hindu society.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Swami Vivekananda

Vivekananda’s fame derived from lectures on Hinduism that he delivered in flamboyant, saffron-robed style across America and Europe in the 1890s. But even as he took those audiences by storm (“I give them spirituality, and they give me money,” he wrote with a wink to one of his Indian patrons), he was deeply shaken by his first encounters with an egalitarianism and social progressiveness that his fellow Hindus lacked. Visiting a Massachusetts women’s penitentiary, he was astonished by the dignity even criminals were afforded. “Oh, how my heart ached to think of what we think of the poor, the low in India,” he wrote to a friend back home. “They have no chance, no escape, no way to climb up … They have forgotten that they too are men. And the result is slavery.”

The contradictions lacing Vivekananda’s speeches and letters – on whether caste was integral to Hinduism, on the validity of certain Hindu rituals and customs – intimate the depth of his intellectual struggle, and one of his greatest internal conflicts was with the effect of his faith on the powerless. “No religion on earth preaches the dignity of humanity in such a lofty strain as Hinduism,” he would write, “and no religion treads upon the necks of the poor and low in such a fashion as Hinduism.” But such contours in Vivekananda’s personality and intellectual life got flattened during his conversion into a laminated image: that of righteous Hindu nationalist avenger of the Muslim and colonial conquests of India, ambivalent about nothing at all.

***

In modern India, writers and historians have been intimidated – and libraries and bookshops ransacked – when they have dared to treat vaunted figures as historical beings. By insisting that favourites from India’s past be preserved in memory as godlike, full of certitude and above human consideration, we don’t just deny them their real natures, we sabotage their exemplary force.

Indian sexism being even more deeply rooted than racism, I can’t claim I was surprised to find that there were far fewer historical records for significant female lives than there were for their male counterparts. But what I saw more clearly is how an absence of documentary sources plays into our ridiculous cultural tendency to turn real women of intellect, judgment, fallibility and bravery into goddess-types

.

The Accession of the Queen of India, 1858. Illustration: Print Collector/Getty Images

Consider Lakshmi Bai (1828-1858), the Rani or Queen of Jhansi, who gained mythic status in the colonial and nationalist Indian imagination because of her resistance to British rule during the uprising of 1857. Today, Indian schoolchildren know her for a single iconic image: astride a leaping horse, sword raised high, with her adopted son clinging to her back. The British military are about to conquer her fort, and instead of surrendering, she is making a dramatic midnight escape from the ramparts.

When I looked down from the fort walls she supposedly leapt from, only one word came to mind: “Splat.” An itinerant priest hiding in her fort at the time described a more plausible exit scenario: down a back staircase and into the night-black hills. For their part, the British preserved the queen in memory as a tempestuous 19th-century villainess. “This Jezebel Ranee”, as a British officer termed her, has since animated a host of adventure and romance novels.

Neither western nor Indian tales leave much room for the actual, practical, Earth-bound person who ruled over a mid-sized kingdom around 400km south of Delhi. So it is a relief to gain, from the priest’s observations, a glimpse of the sort of woman rarely seen in royal Indian annals. This strong-willed queen is athletic (weightlifting, wrestling and steeplechase were just her pre-breakfast routine); indifferent to regal trappings (in contrast to her crossdressing husband); and hands-on as a ruler (so much so that she punished criminals herself, with the whack of a stick).

Following the death of her husband, the land-hungry British annexed Jhansi under a doctrine that enabled them to snaffle up princely states. Lakshmi Bai tried to get her dominion back through a series of frustrating negotiations, but when diplomacy faltered, she decided that rebelling sepoys marching from the north in 1857 might help strengthen her claims. After she harboured them in her fort, though, they massacred British officers and their families, upon which the British bombed her fort, then breached the walls. Two months after her escape, they killed her.

To ascribe to Lakshmi Bai motivations more complex than protonational ones, or escapes that chime with the laws of physics, isn’t to cut her down to size; it is to acknowledge a woman whose independence and unconventionality are qualities more relevant to contemporary women then supposed supernatural powers.

Given how little documentation we have of powerful women in the pre-independence pantheon, what is lost when we turn away from real historical evidence is painful. Take a 20th-century icon from a different realm: the magnificent south Indian classical singer MS Subbulakshmi. Born in 1916 into the Devadasi tradition – a lineage of temple courtesans, whose job was to entertain and serve rich and upper-caste men – she built a career that took her from Madurai temple custom to film stardom to the embodiment of independent India’s national culture

The Accession of the Queen of India, 1858. Illustration: Print Collector/Getty Images

Consider Lakshmi Bai (1828-1858), the Rani or Queen of Jhansi, who gained mythic status in the colonial and nationalist Indian imagination because of her resistance to British rule during the uprising of 1857. Today, Indian schoolchildren know her for a single iconic image: astride a leaping horse, sword raised high, with her adopted son clinging to her back. The British military are about to conquer her fort, and instead of surrendering, she is making a dramatic midnight escape from the ramparts.

When I looked down from the fort walls she supposedly leapt from, only one word came to mind: “Splat.” An itinerant priest hiding in her fort at the time described a more plausible exit scenario: down a back staircase and into the night-black hills. For their part, the British preserved the queen in memory as a tempestuous 19th-century villainess. “This Jezebel Ranee”, as a British officer termed her, has since animated a host of adventure and romance novels.

Neither western nor Indian tales leave much room for the actual, practical, Earth-bound person who ruled over a mid-sized kingdom around 400km south of Delhi. So it is a relief to gain, from the priest’s observations, a glimpse of the sort of woman rarely seen in royal Indian annals. This strong-willed queen is athletic (weightlifting, wrestling and steeplechase were just her pre-breakfast routine); indifferent to regal trappings (in contrast to her crossdressing husband); and hands-on as a ruler (so much so that she punished criminals herself, with the whack of a stick).

Following the death of her husband, the land-hungry British annexed Jhansi under a doctrine that enabled them to snaffle up princely states. Lakshmi Bai tried to get her dominion back through a series of frustrating negotiations, but when diplomacy faltered, she decided that rebelling sepoys marching from the north in 1857 might help strengthen her claims. After she harboured them in her fort, though, they massacred British officers and their families, upon which the British bombed her fort, then breached the walls. Two months after her escape, they killed her.

To ascribe to Lakshmi Bai motivations more complex than protonational ones, or escapes that chime with the laws of physics, isn’t to cut her down to size; it is to acknowledge a woman whose independence and unconventionality are qualities more relevant to contemporary women then supposed supernatural powers.

Given how little documentation we have of powerful women in the pre-independence pantheon, what is lost when we turn away from real historical evidence is painful. Take a 20th-century icon from a different realm: the magnificent south Indian classical singer MS Subbulakshmi. Born in 1916 into the Devadasi tradition – a lineage of temple courtesans, whose job was to entertain and serve rich and upper-caste men – she built a career that took her from Madurai temple custom to film stardom to the embodiment of independent India’s national culture

.

MS Subbulakshmi

Standing in her modest childhood home, on an alleyway near a temple, I mentally tallied the series of steely calculations that launched the stigmatised, artistic child of a single mother into the Indian cultural canon. Once her prodigious gift was recognised, she broke with her mother and her home town, took a renowned musician and then a canny manager as lovers, and sought out the musicians she admired most, to help develop her talent. The few letters of hers not destroyed by image keepers are rife with attitude and passion. But her public persona was, and remains – she died aged 88 in 2004 – that of a demure housewife whose accomplishments were simply visited upon her by the gods. As in other stories of exceptional, hard-working Indian women, volition and ambition are denied their rightful roles.

***

A different narrowing of historical understanding happens when an individual is turned into a representative emblem of his group. Take Bhimrao Ambedkar, who was born an untouchable (as Dalits were formerly known) and then made himself one of the most educated men in India. Acquiring PhDs from the LSE and Columbia University, where his professors included the pragmatist philosopher John Dewey, Ambedkar returned home with a vision of India’s future unique among his mostly upper-caste nationalist contemporaries. Invited by them to play an important role in writing the Indian Constitution, he managed to implant within it some of its most radical ideas, including the principle of affirmative action.

In my travels I heard people of higher castes described Ambedkar as “the big boss” of the Dalits– as if Ambedkar was of no particular concern to other Indians. That chiselled-down identity made me wince, because he is also one of the 20th-century’s great, cranky public intellectuals, of any nation– India’s Tocqueville, really, with enduring insights into the structure and psychology of democracy in general. Where India’s nationalist elite put faith in parliaments and political rights, economic development, or social and cultural reform, Ambedkar saw educational equality as the essential bedrock of a truly democratic society. He understood the limitations of constitutions, and, in a prescient analysis, he argued that without the parity and fraternity created by making education equally accessible to Indians of every background and caste, social barriers would prevail and all efforts at reforming society (including radical ones) would founder.

***

British imperialists liked to suggest Indians were indifferent to their history, and inept at independent thinking to boot, because of their attachment to doll-like gods and caste rituals. This was a self-justifying analysis, of course, given that the Raj was pillaging the subcontinent’s historical wealth with the same voraciousness as it had plundered the teakwood and tea. Still, it was a longstanding colonial habit to picture the empire’s jewel as a congeries of religions, castes and languages: in effect, a black hole of community belonging and identity, from which few flickers of individuality escaped.

MS Subbulakshmi

Standing in her modest childhood home, on an alleyway near a temple, I mentally tallied the series of steely calculations that launched the stigmatised, artistic child of a single mother into the Indian cultural canon. Once her prodigious gift was recognised, she broke with her mother and her home town, took a renowned musician and then a canny manager as lovers, and sought out the musicians she admired most, to help develop her talent. The few letters of hers not destroyed by image keepers are rife with attitude and passion. But her public persona was, and remains – she died aged 88 in 2004 – that of a demure housewife whose accomplishments were simply visited upon her by the gods. As in other stories of exceptional, hard-working Indian women, volition and ambition are denied their rightful roles.

***

A different narrowing of historical understanding happens when an individual is turned into a representative emblem of his group. Take Bhimrao Ambedkar, who was born an untouchable (as Dalits were formerly known) and then made himself one of the most educated men in India. Acquiring PhDs from the LSE and Columbia University, where his professors included the pragmatist philosopher John Dewey, Ambedkar returned home with a vision of India’s future unique among his mostly upper-caste nationalist contemporaries. Invited by them to play an important role in writing the Indian Constitution, he managed to implant within it some of its most radical ideas, including the principle of affirmative action.

In my travels I heard people of higher castes described Ambedkar as “the big boss” of the Dalits– as if Ambedkar was of no particular concern to other Indians. That chiselled-down identity made me wince, because he is also one of the 20th-century’s great, cranky public intellectuals, of any nation– India’s Tocqueville, really, with enduring insights into the structure and psychology of democracy in general. Where India’s nationalist elite put faith in parliaments and political rights, economic development, or social and cultural reform, Ambedkar saw educational equality as the essential bedrock of a truly democratic society. He understood the limitations of constitutions, and, in a prescient analysis, he argued that without the parity and fraternity created by making education equally accessible to Indians of every background and caste, social barriers would prevail and all efforts at reforming society (including radical ones) would founder.

***

British imperialists liked to suggest Indians were indifferent to their history, and inept at independent thinking to boot, because of their attachment to doll-like gods and caste rituals. This was a self-justifying analysis, of course, given that the Raj was pillaging the subcontinent’s historical wealth with the same voraciousness as it had plundered the teakwood and tea. Still, it was a longstanding colonial habit to picture the empire’s jewel as a congeries of religions, castes and languages: in effect, a black hole of community belonging and identity, from which few flickers of individuality escaped.

A procession held in 2015 to mark the anniversary of the birth of Bhim Rao Ambedkar in Mumbai, India. Photograph: Rafiq Maqbool/AP

And weren’t those minimally individuated Indians gentle and spiritual as they waited for their next karmic promotion? I was therefore delighted, visiting Mysore, to hold a tray bearing a palm leaf manuscript from around the turn of the Christian millennium that, when rediscovered a century ago, summarily exploded such cliches. The Arthashastra, a detailed treatise on statecraft and the art of government, gave counsel to kings that made Machiavelli’s look milquetoast (one gets a hint from the chapter titles, which feel as if they were written this year, perhaps by a parliamentary investigative committee: “Establishment of Clandestine Operatives”, “Pacifying a Territory Gained”, “Surveillance of People with Secret Income” and “Investigation through Interrogation and Torture”). The author was a man known as Kautilya, and, though all we have of him is this text, it gives a tantalising rebuttal to suggestions that ancient Indian interests were primarily spiritual.

As I worked, I was moved by how many of the 50 lives I studied posed pointed challenges to the Indian present

As does another work of analytic intellect, by the 5BCE master of the Sanskrit language, Panini. In what amounts to a mere 40 pages, he created the most complete linguistic system in history. This masterwork, known as The Ashtadhyayi, helped make Sanskrit the lingua franca of the Asian world for more than 1,000 years. Today, Panini’s system would be called a generative grammar, something modern linguistic philosophers such as Noam Chomsky and his students have been working for the past half century to develop. It is arguably from the Sanskrit tradition – whose logic Panini helped explain – that India’s present-day century software revolution emerged. And then there’s Ramanujan, the young mathematics prodigy whose century-old notebook scribblings are, as we speak, helping other scientists unravel the nature of the universe. Perhaps there’s something mystical there, in the postulates of quantum physics; though I don’t think it’s what the colonialists had in mind.

***

Other western misperceptions still present themselves on a daily basis – for instance, the notion that social conditions are uniformly dismal across India. Consider the unaddressed crimes and daily oppressions against Indian women, which have rightly provoked international outrage. Draw closer, and you will see that the outrage obscures telling differences between the opportunities for women in northern India and women in the more progressive south, where child marriage and fertility rates are far lower, and female literacy and work participation rates far higher. Some of that divergence has to do not with culture, but with reform-inspired historical crusades – including one led by a Tamil primary-school dropout known as Periyar (1879-1973).