'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Friday, 12 July 2024

Monday, 20 November 2023

Thursday, 17 August 2023

What India’s foreign-news coverage says about its world-view

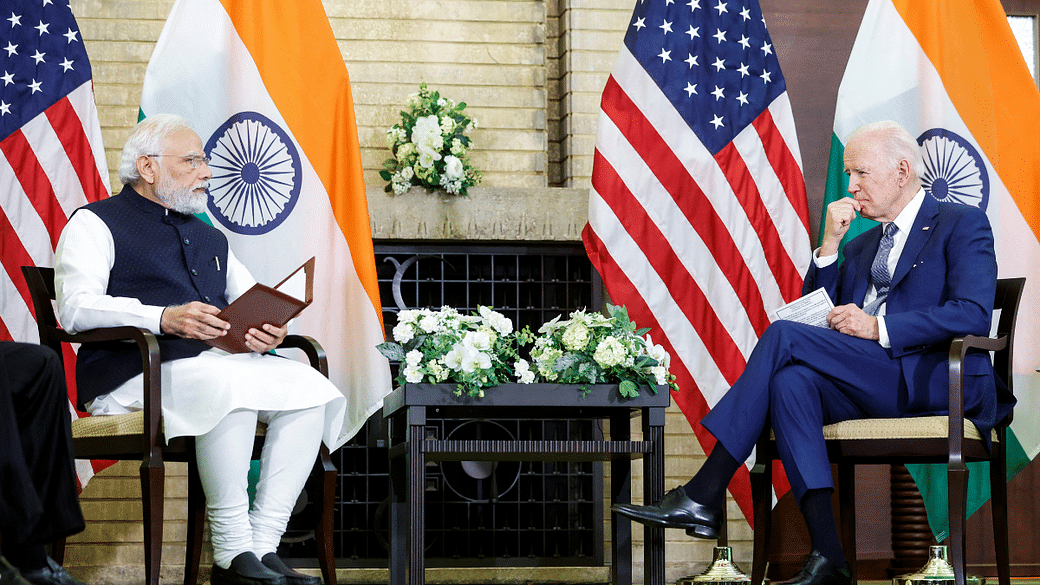

When Narendra Modi visited Washington in June, Indian cable news channels spent days discussing their country’s foreign-policy priorities and influence. This represents a significant change. The most popular shows, which consist of a studio host and supporters of the Hindu-nationalist prime minister jointly browbeating his critics, used to be devoted to domestic issues. Yet in recent years they have made room for foreign-policy discussion, too.

Much of the credit for expanding Indian media’s horizons goes to Mr Modi and his foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, who have skilfully linked foreign and domestic interests. What happens in the world outside, they explain, affects India’s future as a rising power. Mr Modi has also given the channels a lot to discuss; a visit to France and the United Arab Emirates in July was his 72nd foreign outing. India’s presidency of the G20 has brought the world even closer. Meetings have been scheduled in over 30 cities, all of which are now festooned with G20 paraphernalia.

Yet it is hard to detect much deep interest in, or knowledge of, the world in these developments. There are probably fewer Indian foreign correspondents today than two decades ago, notes Sanjaya Baru, a former editor of the Business Standard, a broadsheet. The new media focus on India’s role in the world tends to be hyperpartisan, nationalistic and often stunningly ill-informed.

This represents a business opportunity that Subhash Chandra, a media magnate, has seized on. In 2016 he launched wion, or “World Is One News”, to cover the world from an Indian perspective. It was such a hit that its prime-time host, Palki Sharma, was poached by a rival network to start a similar show.

What is the Indian perspective? Watch Ms Sharma and a message emerges: everywhere else is terrible. Both on wion and at her new home, Network18, Ms Sharma relentlessly bashes China and Pakistan. Given India’s history of conflict with the two countries, that is hardly surprising. Yet she also castigates the West, with which India has cordial relations. Europe is taunted as weak, irrelevant, dependent on America and suffering from a “colonial mindset”. America is a violent, racist, dysfunctional place, an ageing and irresponsible imperial power.

This is not an expression of the confident new India Mr Modi claims to represent. Mindful of the criticism India often draws, especially for Mr Modi’s Muslim-bashing and creeping authoritarianism, Ms Sharma and other pro-Modi pundits insist that India’s behaviour and its problems are no worse than any other country’s. A report on the recent riots in France on Ms Sharma’s show included a claim that the French interior ministry was intending to suspend the internet in an attempt to curb violence. “And thank God it’s in Europe! If it was elsewhere it would have been a human-rights violation,” she sneered. In fact, India leads the world in shutting down the internet for security and other reasons. The French interior ministry had anyway denied the claim a day before the show aired.

Bridling at lectures by hypocritical foreign powers is a longstanding feature of Indian diplomacy. Yet the new foreign news coverage’s hyper-defensive championing of Mr Modi, and its contrast with the self-confident new India the prime minister describes, are new and striking. Such coverage has two aims, says Manisha Pande of Newslaundry, a media-watching website: to position Mr Modi as a global leader who has put India on the map, and to promote the theory that there is a global conspiracy to keep India down. “Coverage is driven by the fact that most tv news anchors are propagandists for the current government.”

This may be fuelling suspicion of the outside world, especially the West. In a recent survey by Morning Consult, Indians identified China as their country’s biggest military threat. America was next on the list. A survey by the Pew Research Centre found confidence in the American president at its highest level since the Obama years. But negative views were also at their highest since Pew started asking the question.

That is at odds with Mr Modi’s aim to deepen ties with the West. And nationalists are seldom able to control the forces they unleash. China has recently sought to tamp down its aggressive “wolf-warrior diplomacy” rhetoric. But its social media remain mired in nationalism. Mr Modi, a vigorous champion for India abroad, should take note. By letting his propagandists drum up hostility to the world, he is laying a trap for himself.

Friday, 23 June 2023

Attacking Modi in US shows IAMC using Indian Muslims as pawns

While PM Modi’s state visit to the US is being noticed across world capitals, his opponents in the US are busy doing what they love most — criticising him for his human rights record and accusing his government of suppressing dissent and implementing discriminatory policies against Muslims and other minority groups.

It is not uncommon to witness certain groups initiating campaigns on foreign soil, portraying a narrative of persecution of Indian Muslims. Raising one’s voice for human rights is indeed a crucial and meaningful endeavour. However, challenges arise when human rights issues are exploited as a tool for propaganda, distorting and manipulating the truth about a nation.

Being an Indian Pasmanda Muslim, I frequently witness the propagation of these false narratives against my homeland. Hence it is my sincere duty to raise my voice against them. India, as a nation, not only embraces the homeland of over one billion Hindus but also stands as a diverse abode for 200 million Muslims, 28 million Christians, 21 million Sikhs, 12 million Buddhists, 4.45 million Jains, and countless others.

It is truly disheartening to witness the portrayal of a nation with such a rich and inclusive history as a place where Muslims are purportedly on the verge of facing genocide. Such narratives often rely on select stories, and it is concerning that the Western media often accepts them without delving into the ground realities and comprehending the policies implemented by the Indian State. It is important for such storytellers to seek a more nuanced understanding by examining the comprehensive picture and taking into account the complexities and intricacies.

To begin with, organisations like the Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC) claim to represent the voice of Indian Muslims. However, they frequently disseminate false and misleading information through their tweets. Moreover, there have been instances where their tweets have been provocative and inflammatory. For instance, they tweeted an unsubstantiated claim stating that all victims in the Delhi riots were Muslims. This organisation has scheduled a protest outside the White House, which raises legitimate questions about their true intentions– do they genuinely prioritise the welfare of Indian Muslims or have ulterior motives and agendas at play?

Indian Muslims, stop being a pawn of anti-India forces

It is high time the Western media and geopolitical interest groups refrain from exploiting the term “Indian Muslims” for their own agendas. As for Indian Muslims, it is important that they themselves comprehend how they are being manipulated as pawns on the global stage, working against their own nation’s interests. It is imperative for them to speak out against these false narratives. We lead peaceful lives, enjoy equal rights and opportunities, have the freedom to practise our religion and make choices, and receive our fair share of benefits from welfare schemes run by the government. Our future is intertwined with our nation’s interests, and anything that generates an anti-India narrative ultimately goes against our own well-being.

Organisations like IAMC, which have no genuine connection with Indian Muslims, falsely claim to represent us while using us as pawns to further their own agendas. It is essential for Muslim intellectuals to see through these manipulations. First, the Muslim community was exploited as a mere vote bank. Now there is a risk of them being used as tools to perpetuate an anti-India narrative.

Examine Western media bias

The Western media has consistently portrayed a negative image of India since its Independence. Interestingly, failed states and countries in the middle of civil wars receive minimal attention.

PM Modi, during a national executive meeting of the BJP, clearly expressed a desire for outreach to the Muslim community, acknowledging that many within the community wish to connect with the party. He emphasised the importance of engaging with not only the economically disadvantaged Pasmanda and Bora Muslims but also educated Muslims. Previously, Modi has highlighted the integration of Pasmanda Muslims with the BJP, urging positive programmes to attract their support.

When BJP leaders have made objectionable statements about Muslims, leading to a tense atmosphere in the country, the party has taken disciplinary action against them too. Under the Modi government, a significant number of minority students have received education scholarships, surpassing previous administrations. Muslim women beneficiaries have expressed their gratitude for various government schemes, such as free ration, the abolition of instant divorce practices, free Covid vaccinations, Ujjawala cooking gas connections, and free housing, which have improved their lives. These initiatives demonstrate efforts to ensure the inclusion and well-being of Muslim communities in India.

It is important to address how Western media and human rights organisations often depict Indian Muslims as ostracised and living in a genocidal environment. For instance, the IAMC played a significant role in lobbying against India in 2019, leading to US Commission on International Religious Freedom recommending India to be blacklisted. For four consecutive years, the USCIRF has advised the US administration to designate India as a “Country of Particular Concern.” Ironically, in their assessments, they did not take into account the reality experienced by Indian Muslims. According to Pew Research, 98 per cent of Indian Muslims are free to practise their religion without hindrance. This stark contrast highlights the disconnect between the exaggerated narratives and the ground realities of religious freedom for Indian Muslims.

Don’t weaponise discourse

In their commentary, Western media and human rights organisations fail to carry voices of ordinary Indian Muslims. Providing a comprehensive and accurate understanding, based on data, helps avoid weaponisation of narratives that serve geopolitical interests.

Data often highlights the disparities in perceptions of discrimination among different communities. According to the Pew study, 80 per cent of African-Americans, 46 per cent of Hispanic Americans, and 42 per cent of Asian Americans stated they experience “a lot of discrimination” in the US. In comparison, 24 per cent of Indian Muslims say that there is widespread discrimination against them in India. Furthermore, the majority of Indian Muslims expressed pride in their Indian identity.

These statistics challenge the narrative of widespread persecution of Indian Muslims within their own nation. It raises the question of whether the same level of scrutiny should be applied to the United States, considering the reported discrimination experienced by minority communities there. It prompts us to reflect on whether the labelling of human rights violations should be applied selectively. And what explains the timing of such mongering — just before a State head is about to visit the country.

Saturday, 21 January 2023

Monday, 12 December 2022

How the West fell out of love with economic growth

From The Economist

This year has been a good one for the West. The alliance has surprised observers with its united front against Russian aggression. As authoritarian China suffers one of its weakest periods of growth since Chairman Mao, the American economy roars along. A wave of populism across rich countries, which began in 2016 with Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, looks like it may have crested.

Yet away from the world’s attention, rich democracies face a profound, slow-burning problem: weak economic growth. In the year before covid-19 advanced economies’ gdp grew by less than 2%. High-frequency measures suggest that rich-world productivity, the ultimate source of improved living standards, is at best stagnant and may be declining. Official forecasts suggest that by 2027 per-person gdp growth in the median rich country will be less than 1.5% a year. Some places, such as Canada and Switzerland, will see numbers closer to zero.

Perhaps rich countries are destined for weak growth. Many have fast-ageing populations. Once labour markets are open to women, and university education democratised, an important source of growth is exhausted. Much low-hanging technological fruit, such as the flush toilet, cars and the internet, has been plucked. This growth problem is surmountable, however. Policymakers could make it easier to trade across borders, giving globalisation a boost. They could reform planning to make it possible to build, reducing outrageous housing costs. They could welcome migrants to replace retiring workers. All of these reforms would raise the growth rate.

Growing pains

Unfortunately, economic growth has fallen out of fashion. According to our analysis of data from the Manifesto Project, which collects information on the manifestos of political parties over decades, those in the oecd, a group of mostly rich countries, are about half as focused on growth as they were in the 1980s (see chart 1). Modern politicians are less likely to extol the benefits of free markets than their predecessors, for instance. They are more likely to express anti-growth sentiments, such as positive mentions of government control over the economy.

When they do talk about growth, politicians do so in an unsophisticated manner. In 1994 a reference by Gordon Brown, Britain’s shadow chancellor, to “post neo-classical endogenous growth theory” was mocked, but it at least indicated serious engagement with the issue. Politicians such as Lyndon Johnson, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan offered policies based on a coherent theory of the relationship between individual and state. gdp’s small coterie of modern champions, such as Mr Trump and Liz Truss, offer little more than reheated Reaganism.

Apathy towards growth is not merely rhetorical. Britain hints at a wider loss of zeal. In the 1970s the average budget contained tax reforms worth 2% of gdp. By the late 2010s policies made half as much impact. A paper published in 2020 by Alberto Alesina, a late economist at Harvard University, and colleagues at the imf and Georgetown University measured the significance of structural reforms (such as changes to regulations) over time. In the 1980s and 1990s politicians in advanced economies implemented a large number, making their economies sleeker. By the 2010s, however, they had lost their oomph: reforms practically ground to a halt.

Our analysis of data from the World Bank suggests that progress has slowed still further in recent years, and may even have reversed (see chart 2). The American government introduced 12,000 new regulations in 2021, a rise on recent years. From 2010 to 2020 rich countries’ tariff restrictions imposed on imports doubled. Britain voted for and implemented Brexit. Other countries have turned against immigration. In 2007 almost 6m people, on net, migrated to rich countries. In 2019 the number was down to just 4m.

Governments have also become less friendly to new construction, whether of housing or infrastructure. A paper by Knut Are Aastveit, Bruno Albuquerque and André Anundsen, three economists, finds that American housing “supply elasticities”—ie, the extent to which construction responds to higher demand—have fallen since the housing boom of the 2000s. This is likely to reflect tougher land-use policies and more powerful nimbys. Housing construction across the rich world is about two-thirds its level in that decade.

Politicians prefer splurging the proceeds of what growth exists. Governments are spending a lot more on welfare, such as pensions and, in particular, health care. In 1979 the bottom fifth of American earners received means-tested transfers worth less than a third of their pre-tax income, according to the Congressional Budget Office. By 2018 the figure was more than two-thirds. According to a report in 2019, health spending per person in the oecd will grow at an average annual rate of 3% and reach 10% of gdp by 2030, up from 9% in 2018.

Politics is increasingly an arms race with promises of more money for health care and social protection. “Thirty or 40 years ago it was taken for granted that the elderly were not good candidates for organ transplantation, dialysis or advanced surgical procedures,” Daniel Callahan, an ethicist, has written. “That has changed.” Greater wealth has enabled this. Yet politicians rarely ask whether an extra dollar on health care is the best use of cash. Britons in their 90s receive health and social care that costs the country about £15,000 ($17,000) a year, about half Britain’s gdp per person. Must budgets rise year after year to meet growing demand, even as the price of providing that care is also likely to increase? If yes, where is the limit?

People may see spending on health care and pensions as self-evidently good. But it comes with downsides. More people work in an area where productivity gains, and therefore improvements in overall living standards, are hard to induce. Perfectly fit older people drop out of work to receive a pension. Funding this requires higher taxes or cuts elsewhere. Since the early 1980s government spending across the oecd on research and development, as a share of gdp, has fallen by about a third.

Much of the extra spending comes at times of crisis. Politicians are increasingly concerned with preventing bad things from happening to people or compensating them when they do. The enormous system of credit guarantees, eviction moratoriums and debt forgiveness introduced during the pandemic brought bankruptcies and defaults to a halt. This was radical, but also the thin end of the wedge.

In America, for instance, the federal government has assumed huge contingent liabilities. It guarantees an ever-larger quantity of people’s bank deposits; it forgives student loans; it offers a wide variety of implicit and explicit backstops to everything from airports to highways. We have previously estimated that Uncle Sam is on the hook for liabilities worth more than six times America’s gdp. This year European governments have fallen over themselves to offer financial support to households and firms during the continent’s energy crisis. Even Germany, normally Europe’s most disciplined spender, has allocated funding worth 7% of gdp for this purpose.

No one cheers when a firm goes bust or someone falls into poverty. But the bail-out state makes economies less adaptable, ultimately constraining growth by preventing resources shifting from unproductive to productive uses. Already there is evidence that fiscal help doled out during the pandemic has created more “zombie” firms—those which are going concerns, but which create little economic value. Governments’ huge implicit liabilities also mean higher spending in times of trouble, which reinforces the trend towards higher taxation.

Grey power

Why has the West turned away from growth? One possible answer relates to ageing populations. People who are not working, or are near the end of their working lives, tend to be less interested in getting richer. They will support things which directly benefit them, such as health care, but oppose those that only produce benefits after they are gone, such as immigration or homebuilding. Their turnout at elections tends to be high, so their views carry weight.

Yet Western populations have been ageing for decades, including during the reformist 1980s and 1990s. Thus the change in the environment in which policy is made may play a role. Before social media and 24-hour rolling news it was easier to implement tough reforms. The losers from a policy—a business exposed to greater competition from abroad, say—often had little choice but to suffer in silence. In 1936 Franklin Roosevelt, speaking about opponents to his New Deal, felt able to “welcome” his opponents’ hatred. Now the aggrieved have more ways to complain. As a result, policymakers have more incentive to limit the number of people who lose out, resulting in what Ben Ansell of Oxford University calls “countrywide decision by committee”.

High levels of debt have also constrained policymakers’ room for manoeuvre. Across the g7 group of rich, powerful countries, private debt has risen by the equivalent of 30 percentage points of gdp since 2000. Even small declines in cash flows could make servicing the debt harder. This means politicians quickly intervene when anything goes wrong. Their focus is keeping the show on the road—avoiding a repeat of the financial crisis of 2007-09—rather than accepting pain today as the price of a brighter future.

Quite what would push the West in a new direction is unclear. There is no sign of a shift just yet, beyond the misguided attempts of Mr Trump and Ms Truss. Would another financial crisis do the job? Will a change have to wait until the baby boomers are no longer around? Whatever the answer, until growth speeds up Western policymakers must hope their enemies continue to blunder.

Tuesday, 22 November 2022

Hypocrisy's Penalty Corner

THERE’S been severe criticism, primarily in the Western media, of the gross exploitation of migrant workers in Qatar’s bid to host football’s World Cup that began in Doha last week. There’s more than a grain of truth in the accusation, and there’s dollops of hypocrisy about it.

FIFA President Gianni Infantino brought it out nicely by calling out the Western media’s double standards in what is tantamount to shedding crocodile tears for the exploited workers.

The CNN, unsurprisingly, slammed Infantino’s anger, and quoted human rights groups as describing his comments as “crass” and an “insult” to migrant workers. Why is Infantino convinced that the Western media wallows in its own arrogance?

It is nobody’s secret that migrant workers in the Gulf are paid a pittance, which becomes more deplorable when compared to the enormous riches they help produce. As is evident, the workers’ exploitation is not specific to Qatar’s hosting of a football tournament, but a deeper malaise in which Western greed mocks its moral sermons.

As their earnings with hard labour abroad fetch them more than what they would get at home, the workers become unwitting partners in their own abuse. This has been the unwritten law around the generation of wealth in oil-rich Gulf countries, though their rulers are not alone in the exploitative venture.

Western colluders, nearly all of them champions of human rights, have used the oil extracted with cheap labour that plies Gulf economies, to control the world order. The West and the Gulf states have both benefited directly from dirt cheap workforce sourced from countries like India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the far away Philippines.

Making it considerably worse is the sullen cutthroat competition that has prevailed for decades between workers of different countries, thereby undercutting each other’s bargaining power. The bruising competition is not unknown to their respective governments that benefit enormously from the remittances from an exploited workforce. The disregard for work conditions is not only related to the Gulf workers, of course, but also migrant labour at home. In the case of India, we witnessed the criminal apathy they experienced in the Covid-19 emergency.

Asian women workers in the Gulf face quantifiably worse conditions. An added challenge they face is of sexual exploitation. Cheap labour imported from South Asia, therefore, answers to the overused though still germane term — Western imperialism. Infantino was spot on. Pity the self-absorbed Western press booed him down.

Sham outrage over a Gulf country hosting the World Cup is just one aspect of hypocrisy. A larger problem remains rooted in an undiscussed bias.

Moscow and Beijing in particular have been the Western media’s leading quarries from time immemorial. The boycott of the Moscow Olympics over the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan was dressed up as a moral proposition, which it might have been but for the forked tongue at play. That numerous Olympic contests went ahead undeterred in Western cities despite their illegal wars or support for dictators everywhere was never called out. What the West did with China, however, bordered on distilled criminality.

I was visiting Beijing in September 1993 with prime minister Narasimha Rao’s media team. The streets were lined with colourful buntings and slogans, which one mistook for a grand welcome for the visiting Indian leader. As it turned out the enthusiasm was all about Beijing’s bid to host the 2000 Olympics. It was fortunate Rao arrived on Sept 6 and could sign with Li Peng a landmark agreement for “peace and tranquility” on the Sino-Indian borders. Barely two week later, China would collapse into collective depression after Sydney snatched the 2000 Olympics from Beijing’s clasp. Western perfidy was at work again.

As it happened, other than Sydney and Beijing three other cities were also in the running — Manchester, Berlin and Istanbul — but, as The New York Times noted: “No country placed its prestige more on the line than China.” When the count began, China led the field with a clear margin over Sydney. Then the familiar mischief came into play.

Beijing led after each of the first three rounds, but was unable to win the required majority of the 89 voting members. One voter did not cast a ballot in the final two rounds. After the third round, in which Manchester won 11 votes, Beijing still led Sydney by 40 to 37 ballots. “But, confirming predictions that many Western delegates were eager to block Beijing’s bid, eight of Manchester’s votes went to Sydney and only three to the Chinese capital,” NYT reported. Human rights was cited as the cause. Hypocritically, that concern disappeared out of sight and Beijing hosted a grand Summer Olympics in 2008.

Football is a mesmerising game to watch. Its movements are comparable to musical notes of a riveting symphony. Above all, it’s a sport that cannot be easily fudged with. But its backstage in our era of the lucre stinks of pervasive corruption.

Anger in Beijing burst into the open when it was revealed in January 1999 that Australia’s Olympic Committee president John Coates promised two International Olympic Committee members $35,000 each for their national Olympic committees the night before the vote, which gave the games to Sydney by 45 votes to 43.

The Daily Mail described the “usual equanimity” with which Juan Antonio Samaranch, the then Spanish IOC president, tried to diminish the scam. The allegations against nine of the 10 IOC members accused of graft “have scant foundation and the remaining one has hardly done anything wrong”.

“In a speech to his countrymen,” recalled the Mail, “he blamed the press for ‘overreacting’ to the underhand tactics, including the hire of prostitutes, employed by Salt Lake City to host the next Winter Olympics.” Samaranch sidestepped any reference to the tactics employed by Sydney to stage the Millennium Summer Games.

This reality should never be obscured by other outrages, including the abominable working conditions of Asian workers in Qatar.

Monday, 29 August 2022

Thursday, 17 March 2022

Western values? They enthroned the monster who is shelling Ukrainians today

However repressive his regime, Vladimir Putin was tolerated by the US, Britain and the EU – until he became intolerable

Six days after Vladimir Putin ordered his soldiers into Ukraine, Joe Biden gave his first State of the Union address. His focus was inevitable. “While it shouldn’t have taken something so terrible for people around the world to see what’s at stake, now everyone sees it clearly,” the US president said. “We see the unity among leaders of nations and a more unified Europe, a more unified west.”

In the countdown to the invasion, the Conservative chairman Oliver Dowden flew to Washington to address a thinktank with impeccable links to Donald Trump. “As Margaret Thatcher said to you almost 25 years ago, the task of conservatives is to remake the case for the west,” the cabinet minister told the Heritage Foundation. “She refused to see the decline of the west as our inevitable destiny. And neither should we.”

Western values. The free world. The liberal order. Over the three weeks since Putin declared war on ordinary Ukrainians, these phrases have been slung about more regularly, more loudly and more unthinkingly than at any time in almost two decades. Perhaps like me you thought such puffed-chest language and inane categorisation had been buried under the rubble of Iraq. Not any more. Now they slip out of the mouths of political leaders and slide into the columns of major newspapers and barely an eyebrow is raised. The Ukrainians are fighting for “our” freedom, it is declared, in that mode of grand solipsism that defines this era. History is back, chirrup intellectuals who otherwise happily stamp on attempts by black and brown people to factcheck the claims made for American and British history.

To hold these positions despite the facts of the very recent past requires vat loads of whitewash. Head of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, claims Vladimir Putin has “brought war back to Europe”, as if Yugoslavia and Kosovo had been hallucinations. Condoleezza Rice pops up on Fox to be told by the anchor: “When you invade a sovereign nation, that is a war crime.” With a solemn nod, the former secretary of state to George Bush replies: “It is certainly against every principle of international law and international order.” She maintains a commendably straight face.

None of this is to defend Putin’s brutality. When 55 Ukrainian children are made refugees every minute and pregnant women in hospital are shelled mid-labour, there is nothing to defend. But to frame our condemnations as a binary clash of rival value systems is to absolve ourselves of our own alleged war crimes, committed as recently as this century in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is to pretend “our” wars are just and only theirs are evil, to make out that Afghan boys seeking asylum from the Taliban are inevitably liars and cheats while Ukrainian kids fleeing Russian bombs are genuine refugees. It is a giant and morally repugnant lie and yet elements of it already taint our front pages and rolling-news coverage. Those TV reporters marvelling at the devastation being visited on a European country, as if its coordinates on a map are what counts, are just one example. Another is the newspapers that spent the past 20 years cursing eastern Europeans for having the temerity to settle here legally and now congratulating the British on the warmth of their hearts.

And then there is the unblushing desire expressed by senior pundits and thinktankers that this might end with “regime change” – toppling Putin and installing in the Kremlin someone more congenial to the US and UK and certainly better house-trained. Spotting the flaw here doesn’t require history, it just needs a working memory. The west has already tried regime change in post-communist Russia: Putin was the end product, the man with whom Bill Clinton declared he could do business, rather than the vodka-soused Boris Yeltsin.

Indeed more than that, London and New York are not just guilty of hosting oligarchs – giving them visas, selling on their most valuable real estate and famous businesses – they helped create the oligarchy in Russia. The US and the UK funded, staffed and applauded the programmes meant to “transform” the country’s economy, but which actually handed over the assets of an industrialised and commodity-rich country to a few dozen men with close connections to the Kremlin.

In 1993, the New York Times Magazine ran a profile of a Harvard economist it called “Dr Jeffrey Sachs, Shock Therapist”. It followed Sachs as he toured Moscow, orchestrating the privatisation of Russia’s economy and declaring how high unemployment was a price worth paying for a revitalised economy. His expertise didn’t come for free, but was bankrolled by the governments of the US, Sweden and other major multinational institutions. But its highest cost was borne by the Russian people. A study in the British Medical Journal concluded: “An extra 2.5-3 million Russian adults died in middle age in the period 1992-2001 than would have been expected based on 1991 mortality.” Meanwhile, the country’s wealth was handed over to a tiny gang of men, who took whatever they could out of the country to be laundered in the US and the UK. It was one of the grandest and most deadly larcenies of modern times, overseen by Yeltsin and Putin and applauded and financed by the west.

The western values that are being touted today helped enthrone the monster who is now shelling Ukrainian women and children. However corrupt and repressive his regime, Putin was tolerated by the west – until he became intolerable. In much the same way, until last month Roman Abramovich was perfectly fit and proper to own Chelsea football club. Now No 10 says he isn’t. There are no values here, not even a serious strategy. Today, Boris Johnson claims Mohammed bin Salman is a valued friend and partner to the UK, and sells him arms to kill Yemenis and pretends not to notice those he has executed. Goodness knows what tomorrow will bring.

Saturday, 12 March 2022

Friday, 11 March 2022

‘People Like Us’ – The Reporting On Russia’s War In Ukraine Has Laid Bare Western Media Bias

"Marred with racial prejudice, the coverage of the war tends to normalise such tragedy in other parts of the world," writes Mohammad Jamal Ahmed in The Friday Times

Charlie D’Agata, a CBS news correspondent, commenting on the conflict described Ukraine as a “relatively civilized, relatively European” place in comparison with Iraq and Afghanistan. Such a framing propagates the narrative that wars and conflicts are unacceptable in Europe where the people have “blond hair and blue eyes” and “look like us”, but justifiable elsewhere. After his comments went viral, Charlie D’Agata did issue an apology but this was far from an isolated incident in the bigger picture. There are far too many examples reflecting the prevalent biased mentality in Western journalism.

In the same vein, Daniel Hannan of the Telegraph wrote, “They seem so like us. That is what makes it so shocking. Ukraine is a European country. Its people watch Netflix and have Instagram accounts, vote in free elections, and read uncensored newspapers. War is no longer something visited upon remote and impoverished locations”. Philippe Corbe of BFM TV, a France-based channel, reported, “We are not talking here about Syrian fleeing the bombing of Syrian regime backed by Putin, we are talking about Europeans leaving in cars that look like ours to save their lives.”

When Western interests are at stake, the resistance is labeled as “gallant, brave people fighting for their freedom.” Otherwise, they are mere “barbaric savages” or “terrorists”

This orientalist signalling relies on the notion that our looks and economic factors play a role in determining who is “civilised” or “uncivilised” and whether the war is somehow normal and expected in other areas of the world.

Even Al Jazeera, a Doha-based news outlet, could not refrain from such insensitive and irresponsible comments. Although they did apologise for the comments made by Al Jazeera English commentator Peter Dobbie about how Ukrainians do not “look like refugees” because of how they are dressed and look “middle class”, it shows how deeply ingrained such stereotypes and preconceived notions really are.

The Arab and Middle Eastern Journalists Association issued a statement categorically condemning such “comparisons that weigh the significance or imply justification of one conflict over another.”

Mehdi Hassan, a political analyst, on his show on MSNBC, bluntly called out this blatant hypocrisy, “when they say, ‘Oh, civilised cities’ and, in another clip, ‘Well-dressed people’ and ‘This is not the Third World,’ they really mean white people, don’t they?”

However, this imprudent emergence of biases is not just restricted to journalists.

Santiago Abascal, the leader of Spain’s VOX party, said in parliament, “Anyone can tell the difference between them (Ukrainian refugees) and the invasion of young military-aged men of Muslim origin who have launched themselves against European borders in an attempt to destabilize and colonize it.” Such commentaries enable the expression of racism pervading in the Western society. The mere existence of “men of Muslim origin” is conflated with a threat in itself.

The far-right French presidential candidate Marie Le Pen, rightfully, and very conveniently, recalled the Geneva Convention when posed the question about Ukrainian refugees. However, when she had to acknowledge the plight of the Syrian families seeking refuge in France, she defended her disapproval by stating that France does not have the means and if she were from a war-torn country, she would have stayed and fought.

Bulgaria’s Prime Minister Kiril Petkov said, “These are not the refugees we are used to. They are Europeans, intelligent, educated people… this is not the usual refugee wave of people with an unknown past. No European country is afraid of them.”

Such comments are not unprecedented, they have been emboldened by years of biased coverage of geopolitical events that serve western interests normalizing such narratives.

When America invaded Iraq under the garb of threat from weapons of mass destruction, it was done to “free the Iraqi people” from themselves. It was done in the name of liberation. The Economists’ May 2003 edition was titled “Now the waging of peace”. All it did, however, was leave a trail of destruction and chaos in the region.

The biggest humanitarian crisis is ongoing as you read this, and it is being perpetrated by American bombs and funding to Saudia Arabia. The United Nations Food Agency warns that 13 million Yemenis – nearly half children – are on the brink of starvation. All because of the genocidal US-backed war, yet no outrage on this catastrophe.

In 2014, when Israel killed over 2,300 people in Gaza with their incessant bombing of more than 500 tons of explosives, there was not a single outcry in the Western media outlets. Moreover, Google even allowed games like ‘Bomb Gaza’ to be sold from the play store. Earlier this year, Amnesty International even declared “the only democracy in the Middle East” an apartheid state, yet Western journalists and politicians flocked to its defense.

Just last year, even Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelenksyy defended Israeli apartheid aggression against Palestine. The United States and the European Union continue to support and uphold this “cruel system of domination and crime against humanity”, yet hardly are there any calls for collective action against the perpetrators.

When Western interests are at stake, the resistance is labeled as “gallant, brave people fighting for their freedom.” Otherwise, they are mere “barbaric savages” or “terrorists.”

The framing of the current crisis at the expense of others is abhorrent, at the least. We must show solidarity with civilians under military assault all over the world regardless of their socio-economic factors; for selective justice is injustice.

Monday, 28 February 2022

Tuesday, 25 September 2018

Why western philosophy can only teach us so much

One of the great unexplained wonders of human history is that written philosophy first flowered entirely separately in different parts of the globe at more or less the same time. The origins of Indian, Chinese and ancient Greek philosophy, as well as Buddhism, can all be traced back to a period of roughly 300 years, beginning in the 8th century BC.

These early philosophies have shaped the different ways people worship, live and think about the big questions that concern us all. Most people do not consciously articulate the philosophical assumptions they have absorbed and are often not even aware that they have any, but assumptions about the nature of self, ethics, sources of knowledge and the goals of life are deeply embedded in our cultures and frame our thinking without our being aware of them.

Yet, for all the varied and rich philosophical traditions across the world, the western philosophy I have studied for more than 30 years – based entirely on canonical western texts – is presented as the universal philosophy, the ultimate inquiry into human understanding. Comparative philosophy – study in two or more philosophical traditions – is left almost entirely to people working in anthropology or cultural studies. This abdication of interest assumes that comparative philosophy might help us to understand the intellectual cultures of India, China or the Muslim world, but not the human condition.

This has become something of an embarrassment for me. Until a few years ago, I knew virtually nothing about anything other than western philosophy, a tradition that stretches from the ancient Greeks to the great universities of Europe and the US. Yet, if you look at my PhD certificate or the names of the university departments where I studied, there is only one, unqualified, word: philosophy. Recently and belatedly, I have been exploring the great classical philosophies of the rest of the world, travelling across continents to encounter them first-hand. It has been the most rewarding intellectual journey of my life.

My philosophical journey has convinced me that we cannot understand ourselves if we do not understand others. Getting to know others requires avoiding the twin dangers of overestimating either how much we have in common or how much divides us. Our shared humanity and the perennial problems of life mean that we can always learn from and identify with the thoughts and practices of others, no matter how alien they might at first appear. At the same time, differences in ways of thinking can be both deep and subtle. If we assume too readily that we can see things from others’ points of view, we end up seeing them from merely a variation of our own.

To travel around the world’s philosophies is an opportunity to challenge the beliefs and ways of thinking we take for granted. By gaining greater knowledge of how others think, we can become less certain of the knowledge we think we have, which is always the first step to greater understanding.

Take the example of time. Around the world today, time is linear, ordered into past, present and future. Our days are organised by the progression of the clock, in the short to medium term by calendars and diaries, history by timelines stretching back over millennia. All cultures have a sense of past, present and future, but for much of human history this has been underpinned by a more fundamental sense of time as cyclical. The past is also the future, the future is also the past, the beginning also the end.

The dominance of linear time fits in with an eschatological worldview in which all of human history is building up to a final judgment. This is perhaps why, over time, it became the common-sense way of viewing time in the largely Christian west. When God created the world, he began a story with a beginning, a middle and an end. As Revelation puts it, while prophesying the end times, Jesus is this epic’s “Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last”.

But there are other ways of thinking about time. Many schools of thought believe that the beginning and the end are and have always been the same because time is essentially cyclical. This is the most intuitively plausible way of thinking about eternity. When we imagine time as a line, we end up baffled: what happened before time began? How can a line go on without end? A circle allows us to visualise going backwards or forwards for ever, at no point coming up against an ultimate beginning or end.

Thinking of time cyclically especially made sense in premodern societies, where there were few innovations across generations and people lived very similar lives to those of their grandparents, their great-grandparents and going back many generations. Without change, progress was unimaginable. Meaning could therefore only be found in embracing the cycle of life and death and playing your part in it as best you could.

Confucius (551-479 BC). Photograph: Getty

Perhaps this is why cyclical time appears to have been the human default. The Mayans, Incans and Hopi all viewed time in this way. Many non-western traditions contain elements of cyclical thinking about time, perhaps most evident in classical Indian philosophy. The Indian philosopher and statesman Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan wrote: “All the [orthodox] systems accept the view of the great world rhythm. Vast periods of creation, maintenance and dissolution follow each other in endless succession.” For example, a passage in the Rig Veda addressing Dyaus and Prithvi (heaven and earth) reads: “Which was the former, which of them the latter? How born? O sages, who discerns? They bear themselves all that has existence. Day and night revolve as on a wheel.”

East Asian philosophy is deeply rooted in the cycle of the seasons, part of a larger cycle of existence. This is particularly evident in Taoism, and is vividly illustrated by the surprising cheerfulness of the 4th century BC Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi when everyone thought he should have been mourning for his wife. At first, he explained, he was as miserable as anyone else. Then he thought back beyond her to the beginning of time itself: “In all the mixed-up bustle and confusion, something changed and there was qi. The qi changed and there was form. The form changed and she had life. Today there was another change and she died. It’s just like the round of four seasons: spring, summer, autumn and winter.”

In Chinese thought, wisdom and truth are timeless, and we do not need to go forward to learn, only to hold on to what we already have. As the 19th- century Scottish sinologist James Legge put it, Confucius did not think his purpose was “to announce any new truths, or to initiate any new economy. It was to prevent what had previously been known from being lost.” Mencius, similarly, criticised the princes of his day because “they do not put into practice the ways of the ancient kings”. Mencius also says, in the penultimate chapter of the eponymous collection of his conversations, close to the book’s conclusion: “The superior man seeks simply to bring back the unchanging standard, and, that being correct, the masses are roused to virtue.” The very last chapter charts the ages between the great kings and sages.

A hybrid of cyclical and linear time operates in strands of Islamic thought. “The Islamic conception of time is based essentially on the cyclic rejuvenation of human history through the appearance of various prophets,” says Seyyed Hossein Nasr, professor emeritus of Islamic studies at George Washington University. Each cycle, however, also moves humanity forward, with each revelation building on the former – the dictation of the Qur’an to Muhammad being the last, complete testimony of God – until ultimately the series of cycles ends with the appearance of the Mahdi, who rules for 40 years before the final judgment.

The distinction between linear and cyclical time is therefore not always neat. The assumption of an either/or leads many to assume that oral philosophical traditions have straightforwardly cyclical conceptions of time. The reality is more complicated. Take Indigenous Australian philosophies. There is no single Australian first people with a shared culture, but there are enough similarities across the country for some tentative generalisations to be made about ideas that are common or dominant. The late anthropologist David Maybury-Lewis suggested that time in Indigenous Australian culture is neither cyclical nor linear; instead, it resembles the space-time of modern physics. Time is intimately linked to place in what he calls the “dreamtime” of “past, present, future all present in this place”.

“One lives in a place more than in a time,” is how Stephen Muecke puts it in his book Ancient and Modern: Time, Culture and Indigenous Philosophy. More important than the distinction between linear or cyclical time is whether time is separated from or intimately connected to place. Take, for example, how we conceive of death. In the contemporary west, death is primarily seen as the expiration of the individual, with the body as the locus, and the location of that body irrelevant. In contrast, Muecke says: “Many indigenous accounts of the death of an individual are not so much about bodily death as about a return of energy to the place of emanation with which it re-identifies.”

Such a way of thinking is especially alien to the modern west, where a pursuit of objectivity systematically downplays the particular, the specifically located. In a provocative and evocative sentence, Muecke says: “Let me suggest that longsightedness is a European form of philosophical myopia and that other versions of philosophy, indigenous perhaps, have a more lived-in and intimate association with societies of people and the way they talk about themselves.”

Muecke cites the Australian academic Tony Swain’s view that the concept of linear time is a kind of fall from place. “I’ve got a hunch that modern physics separated out those dimensions and worked on them, and so we produced time as we know it through a whole lot of experimental and theoretical activities,” Muecke told me. “If you’re not conceptually and experimentally separating those dimensions, then they would tend to flow together.” His indigenous friends talk less of time or place independently, but more of located events. The key temporal question is not “When did this happen?” but “How is this related to other events?”

That word related is important. Time and space have become theoretical abstractions in modern physics, but in human culture they are concrete realities. Nothing exists purely as a point on a map or a moment in time: everything stands in relation to everything else. So to understand time and space in oral philosophical traditions, we have to see them less as abstract concepts in metaphysical theories and more as living conceptions, part and parcel of a broader way of understanding the world, one that is rooted in relatedness. Hirini Kaa, a lecturer at the University of Auckland, says that “the key underpinning of Maori thought is kinship, the connectedness between humanity, between one another, between the natural environment”. He sees this as a form of spirituality. “The ocean wasn’t just water, it wasn’t something for us to be afraid of or to utilise as a commodity, but became an ancestor deity, Tangaroa. Every living thing has a life force.”

David Mowaljarlai, who was a senior lawman of the Ngarinyin people of Western Australia, once called this principle of connectivity “pattern thinking”. Pattern thinking suffuses the natural and the social worlds, which are, after all, in this way of thinking, part of one thing. As Muecke puts it: “The concept of connectedness is, of course, the basis of all kinship systems [...] Getting married, in this case, is not just pairing off, it is, in a way, sharing each other.”

The emphasis on connectedness and place leads to a way of thinking that runs counter to the abstract universalism developed to a certain extent in all the great written traditions of philosophy. Muecke describes as one of the “enduring [Indigenous Australian] principles” that “a way of being will be specific to the resources and needs of a time and place and that one’s conduct will be informed by responsibility specific to that place”. This is not an “anything goes” relativism, but a recognition that rights, duties and values exist only in actual human cultures, and their exact shape and form will depend on the nature of those situations.

This should be clear enough. But the tradition of western philosophy, in particular, has striven for a universality that glosses over differences of time and place. The word “university”, for example, even shares the same etymological root as “universal”. In such institutions, “the pursuit of truth recognises no national boundaries”, as one commentator observed. Place is so unimportant in western philosophy that, when I discovered it was the theme of the quinquennial East-West Philosophers’ Conference in 2016, I wondered if there was anything I could bring to the party at all. (I decided that the absence of place in western philosophy itself merited consideration.)

The universalist thrust has many merits. The refusal to accept any and every practice as a legitimate custom has bred a very good form of intolerance for the barbaric and unjust traditional practices of the west itself. Without this intolerance, we would still have slavery, torture, fewer rights for women and homosexuals, feudal lords and unelected parliaments. The universalist aspiration has, at its best, helped the west to transcend its own prejudices. At the same time, it has also legitimised some prejudices by confusing them with universal truths. The philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah argues that the complaints of anti-universalists are not generally about universalism at all, but pseudo-universalism, “Eurocentric hegemony posing as universalism”. When this happens, intolerance for the indefensible becomes intolerance for anything that is different. The aspiration for the universal becomes a crude insistence on the uniform. Sensitivity is lost to the very different needs of different cultures at different times and places.

This “posing as universalism” is widespread and often implicit, with western concepts being taken as universal but Indian ones remaining Indian, Chinese remaining Chinese, and so on. To end this pretence, Jay L Garfield and Bryan W Van Norden propose that those departments of philosophy that refuse to teach anything from non-western traditions at least have the decency to call themselves departments of western philosophy.

The “pattern thinking” of Maori and Indigenous Australian philosophies could provide a corrective to the assumption that our values are the universal ones and that others are aberrations. It makes credible and comprehensible the idea that philosophy is never placeless and that thinking that is uprooted from any land soon withers and dies.

Mistrust of the universalist aspiration, however, can go too far. At the very least, there is a contradiction in saying there are no universal truths, since that is itself a universal claim about the nature of truth. The right view probably lies somewhere between the claims of naive universalists and those of defiant localists. There seems to be a sense in which even the universalist aspiration has to be rooted in something more particular. TS Eliot is supposed to have said: “Although it is only too easy for a writer to be local without being universal, I doubt whether a poet or novelist can be universal without being local, too.” To be purely universal is to inhabit an abstract universe too detached from the real world. But just as a novelist can touch on universals of the human condition through the particulars of a couple of characters and a specific story, so our different, regional philosophical traditions can shed light on more universal philosophical truths even though they approach them from their own specific angles.

We should not be afraid to ground ourselves in our own traditions, but we should not be bound by them. Gandhi put this poetically when he wrote: “I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the cultures of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any. I refuse to live in other people’s houses as an interloper, a beggar or a slave.”

In the west, the predominance of linear time is associated with the idea of progress that reached its apotheosis in the Enlightenment. Before this, argues the philosopher Anthony Kenny, “people looking for ideals had looked backwards in time, whether to the primitive church, or to classical antiquity, or to some mythical prelapsarian era. It was a key doctrine of the Enlightenment that the human race, so far from falling from some earlier eminence, was moving forward to a happier future.”

Kenny is expressing a popular view, but many see the roots of belief in progress deeper in the Christian eschatological religious worldview. “Belief in progress is a relic of the Christian view of history as a universal narrative,” claims John Gray. Secular thinkers, he says, “reject the idea of providence, but they continue to think humankind is moving towards a universal goal”, even though “the idea of progress in history is a myth created by the need for meaning”.

Whether faith in progress is an invention or an adaptation of the Enlightenment, the image of secular humanists naively believing humanity is on an irreversible, linear path of advancement seems to me a caricature of their more modest hope, based in history, that progress has occurred and that more is possible. As the historian Jonathan Israel says, Enlightenment ideas of progress “were usually tempered by a strong streak of pessimism, a sense of the dangers and challenges to which the human condition is subject”. He dismisses the idea that “Enlightenment thinkers nurtured a naive belief in man’s perfectibility” as a “complete myth conjured up by early 20th-century scholars unsympathetic to its claims”.

Nevertheless, Gray is right to point out that linear progress is a kind of default way of thinking about history in the modern west and that this risks blinding us to the ways in which gains can be lost, advances reversed. It also fosters a sense of the superiority of the present age over earlier, supposedly less advanced” times. Finally, it occludes the extent to which history doesn’t repeat itself but does rhyme.

The different ways in which philosophical traditions have conceived time turn out to be far from mere metaphysical curiosities. They shape the way we think about both our temporal place in history and our relation to the physical places in which we live. It provides one of the easiest and clearest examples of how borrowing another way of thinking can bring a fresh perspective to our world. Sometimes, simply by changing the frame, the whole picture can look very different.

Sunday, 20 May 2018

To Save Western Capitalism - Look East

Once upon a time, not so long ago, there was a place where peace and prosperity reigned. Let’s call this place the West. These lands had once been ravaged by bloody wars but its rulers had, since, solved the puzzle of perpetual progress and discovered a kind of political and economic elixir of life. Big Problems were relegated to either Somewhere Else (the East) or Another Time (History). The Westerners dutifully sent emissaries far and wide to spread the word that the secret of eternal bliss had been found –and were, themselves, to live happily ever after.

So ran, until very recently, the story of how the West was won.

The formula that had been discovered was simple: the recipe for a bright, shiny new brand of global capitalism based on liberal democracy and something called neoclassical economics. But it was different from previous eras – cleansed of Dickensian grime. The period after the two world wars was in many a Golden Age: the moment of Bretton Woods (that established the international monetary and financial order) and the Beveridge report (the blueprint for the welfare state), feminism and free love.

It was post-colonial, post-racial, post-gendered. It felt like you could have it all, material abundance and the moral revolutions; a world infinitely vulnerable to invention – but all without picking sides, all based on institutional equality of access. That’s how clever the scheme was – truly a brave new world. Fascism and class, slavery and genocide – no one doubted that, in the main, it had been left behind (or at least that we could all agree on its evils); that the wheels of history had permanently been set in motion to propel us towards a better future. The end of history, Francis Fukuyama called it – the zenith of human civilisation.

Austerity in Athens: the eurozone crisis hit Greece not once but twice (Getty)

While liberal democracy was the part of the programme that got slapped on to the brochure, it was a streamlined paradigm of neoclassical economics that provided the brains behind the enterprise. Neoclassical economics, scarred by war-era ideological acrimony, scrubbed the subject of all the messy stuff: politics, values – all the fluff. To do so it used a new secret weapon: quantitative precision unprecedented in the social sciences.

It didn’t rest on whimsical things like enlightened leadership or invested citizenship or compassionate communities. No, siree. It was pure science: a reliable, universally-applicable maximising equation for society (largely stripped of any contextual or, until recently, even cognitive considerations). Its particular magic trick was to be able to do good without requiring anyone to be good.

And, it was limitless in its capacity to turn boundless individual rationality into endless material wellbeing, to cull out of infinite resources (on a global scale) indefinite global growth. It presumed to definitively replace faltering human touch with the infallible “invisible hand” and, so, discourses of exploitation with those of merit.

When I started as a graduate student in the early 2000s, this model was at the peak of its powers: organised into an intellectual and policy assembly line that more or less ran the world. At the heart of this enterprise, in the unipolar post-Cold War order, was what was known as the Chicago school of law and economics. The Chicago school boiled the message of neoclassical economics down to a simpler formula still: the American Dream available for export – just add private property and enforceable contracts. Anointed with a record number of Nobel prizes, its message went straight to the heart of Washington DC, and from there – via its apostles, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank radiated out to the rest of the globe.

It was like the social equivalent of the Genome project. Sure the model required the odd tweak, the ironing out of the occasional glitch but, for the most part, the code had been cracked. So, like the ladies who lunch, scholarly attention in the West turned increasingly to good works and the fates of “the other” – spatially and temporally.

One strain led to a thriving industry in development: these were the glory days of tough love, and loan conditionalities. The message was clear: if you want Western-style growth, get with the programme. The polite term for it was structural adjustment and good governance: a strict regime of purging what Max Weber had called mysticism and magic, and swapping it for muscular modernisation. Titles like Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson’s Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty and Hernando de Soto’s The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else jostled for space on shelves of bookstores and best-seller lists.

Another led to esoteric islands of scholarship devoted to atonement for past sins. On the US side of the Atlantic, post-colonial scholarship gained a foothold, even if somewhat limp. In America, slavery has been, for a while now, the issue a la mode. A group of Harvard scholars has been taking a keen interest in the “history of capitalism”.

Playing intellectual archaeologists, they’ve excavated the road that led to today’s age of plenty – leaving in its tracks a blood-drenched path of genocide, conquest, and slavery. The interest that this has garnered, for instance Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton, is heartening, but it has been limited to history (or worse still, “area studies”) departments rather than economics, and focused on the past not the present.

As far back as the fifties ... the economy was driving the society, when it should have been the other way around (Getty)

Indeed, from the perspective of Western scholarship, the epistemic approach to the amalgam of these instances has been singularly inspired by Indiana Jones – dismissed either as curious empirical aberrations or distanced by the buffer of history. By no means the stuff of mainstream economic theory.

Some of us weakly cleared our throats and tried to politely intercede that there were, all around us, petri dishes of living, breathing data on not just development – but capitalism itself. Maybe, just maybe – could it be? – that if the template failed to work in a large majority of cases around the globe that there may be a slight design error.

My longtime co-author, Nobel Prize winner in Economics and outspoken critic, Joseph Stiglitz, in his 1990 classic Globalisation and Its Discontents chronicled any number of cases of leaching-like brutality of structural adjustment. The best-selling author and my colleague at Cambridge, Ha-Joon Chang, in Kicking Away the Ladder, pointed out that it was a possibility that the West was misremembering the trajectory of its own ascent to power – that perhaps it was just a smidgen more fraught than it remembered, that maybe the State had had a somewhat more active part to play before it retired from the stage.

But a bright red line separated the “us” from the “them” enforcing a system of strict epistemic apartheid. Indeed, as economics retreated further and further into its silo of smugness, economics departments largely stopped teaching economic history or sociology and development economics clung on by operating firmly within the discipline-approved methodology.

So far, so good – a bit like the last night of merriment on the Titanic. Then the iceberg hit.

Suddenly the narratives that were comfortably to do with the there and then became for the Western world a matter of the here and now.

In the last 10 years, what economic historian Robert Skidelsky recently referred to as the “lost decade” for the advanced industrial West, problems that were considered the exclusive preserve of development theory – declining growth, rampant inequality, failing institutions, a fractured political consensus, corruption, mass protests and poverty – started to be experienced on home turf.

The Great Recession starting 2008 should really have been the first hint: foreclosures and evictions, bankruptcies and bailouts, crashed stock markets. Then came the eurozone crisis starting in 2009 (first Greece; then Ireland; then Portugal; then Spain; then Cyprus; oh, and then Greece, again). But after an initial scare, it was largely business as usual – written off as an inevitable blip in the boom-bust logic of capitalist cycles. It was 2016, the year the world went mad, that made the writing on the wall impossible to turn away from – starting with the shock Brexit vote, and then the Trump election. Not everyone understands what a CDO (collateralised debt obligation) is, but the vulgarity of a leader of the free world who governs by tweet and “grabs pussy” is hard to miss.

So how did it happen, this unexpected epilogue to the end of history?

I hate to say I told you so, but some of us had seen this coming – the twist in the tale, foreshadowed by an eerie background score lurking behind the clinking of champagne glasses. Even at the height of the glory days. In the summer before the fall of Lehman Brothers, a group of us “heterodox economists” had gathered at a summer school in the North of England. We felt like the audience at a horror movie – knowing that the gory climax was moments away while the victim remained blissfully impervious.

The plot wasn’t just predictable, it was in the script for anyone to see. You just had to look closely at the fine print.

In particular, you needed to have read your Karl Polanyi, the economic sociologist, who predicted this crisis over 50 years ago. As far back as 1954, The Great Transformation diagnosed the central perversion of the capitalist system, the inversion that makes the person less important than the thing – the economy driving society, rather than the other way around.

Polanyi’s point was simple: if you turned all the things that people hold sacred into grist to the mill of a large impersonal economic machinery (he called this disembedding) there would be a backlash. That the fate of a world where monopoly money reigns supreme and human players are reduced to chessmen at its mercy is doomed. The sociologist Fred Block compares this to the stretching of a giant elastic band – either it reverts to a more rooted position, or it snaps.

It is this tail-wagging-the-dog quality that is driving the current crisis of capitalism. It’s a matter of existential alienation. This problem of artificial abstraction runs through the majority of upheavals of our age – from the financial crisis to Facebook. So cold were the nights in this era of enforced neutrality that the torrid affair between liberal democracy and neoclassical economics resulted in the most surprising love child – populism.

The simple fact is that after decades on promises not delivered on, the system had written just one too many cheques that couldn’t be cashed. And people had had just about enough.

The Brexit vote in 2016 followed by the election of Trump ... and the world had finally gone mad (Getty)

The old fault lines of global capitalism, the East versus West dynamics of the World Trade Organisation’s Doha Round, turned out to be red herrings. The axis that counts is the system versus the little people. Indeed, the anatomies of annihilation look remarkably similar across the globe – whether it’s the loss of character of a Vanishing New York or Disappearing London, or threatened communities of farmers in India and fishermen in Greece.

Trump voters in the US, Brexiteers in Britain and Modi supporters in India seek identity – any identity, even a made-up call to arms to “return” to mythical past greatness in the face of the hollowing out of meaning of the past 70 years. The rise of populism is, in many ways, the death cry of populations on the verge of extinction – yearning for something to believe in when their gods have died young. It’s a problem of the 1 per cent – poised to control two-thirds of the world economy by 2030 – versus the 99 per cent. But far more pernicious is the Frankenstein’s monster that is the idea of an economic system that is an end in itself.

Not to be too much of a conspiracy theorist about it, but the current system doesn’t work because it wasn’t meant to – it was rigged from the start. Wealth was never actually going to “trickle down”. Thomas Piketty did the maths.

Suddenly, the alarmist calls of the developmentalists objecting to the systemic skews in the process of globalisation don’t seem quite so paranoid.

But this is more than “poco” (what the cool kids call postcolonialism) schadenfreude. My point is a serious one; although I would scarcely have dared articulate it before now. Could Kipling have been wrong, and might the East have something to offer the mighty West? Could the experiences of exotic lands point the way back to the future? Could it be, could it just, that it may even be a source of epistemic wisdom?

Behind the scaffolding of Xi Jinping’s China or Narendra Modi’s India, sites of capitalism under construction, we are offered a glimpse into the system’s true nature. It is not God-given, but the product of highly political choices. Just like Jane Jacobs protesting to save Washington Square Park or Beatrix Potter devoting the bulk of her royalty earnings to conserving the Lake District were choices. But these cases also show that trust and community are important. The incredible resilience of India’s jugaad economy, or the critical role of quanxi in the creation of the structures in what has been for the past decade the world’s fastest-growing nation, China. A little mysticism and magic may be just the thing.

The narrative that we need is less that of Frankenstein’s man-loses-control of monster, and more that of Pinocchio’s toy-becomes-real-boy-by-acquiring-conscience; less technology, and more teleology. The real limit may be our imaginations. Perhaps the challenge is to do for scholarship, what Black Panther has done for Hollywood. You never know. Might be a blockbuster.