'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Friday, 12 July 2024

Saturday, 22 January 2022

Monday, 25 January 2021

Why you should ditch ‘follow your passion’ careers advice

Emma Jacobs in The FT

“Work is supposed to bring us fulfilment, pleasure, meaning, even joy,” writes Sarah Jaffe in her book, Work Won’t Love You Back. “The admonishment of a thousand inspirational social media posts to ‘do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life’ has become folk wisdom,” she continues.

Such platitudes suggest an essential truth “stretching back to our caveperson ancestors”. But these fallacies create “stress, anxiety and loneliness”. In short, the “labour of love . . . is a con”. This is the starting point of Ms Jaffe’s book, which goes on to show how the myth permeates diverse jobs and sectors.

---

---

The book serves as a timely reminder of the importance of re-evaluating that relationship. “The global pandemic made the brutality of the workplace more visible,” the author tells me over the phone from Brooklyn, New York. Ms Jaffe, who is a freelance journalist specialising in work, points out that the past year of job losses, anxiety about redundancy, and excessive workloads has demonstrated to workers the truth: their job does not love them.

Work is under scrutiny. The economic fallout of the pandemic has made a great many people desperate for paid work, disillusioned with their jobs or burnt out — and sometimes all three. It has illuminated the stark differences between those who can work from the safety of their homes and those who cannot, including shop workers, carers and medical professionals, who have to put themselves in potentially hazardous situations, often for meagre pay. The idea of self-sacrifice, and that you should put your clients, your patients or your students before yourself, Ms Jaffe says, “gets laid on very thick [with] teachers or nurses”.

Yet there are those in another category — artists and precarious academics — for whom work has always been deemed intrinsically rewarding and a form of self-expression. They are said to be lucky to have such jobs, because plenty of others are clamouring to take their place. Even here, the pandemic has changed perceptions. Social restrictions have curbed some of the aspects of white-collar work that made it rewarding, such as travel and meeting interesting people, that perhaps masked the repetition of daily tasks, the insecurity or poor conditions.

Meanwhile, Ms Jaffe says, a small number of workers, such as those who have been furloughed on full pay, have been given the time to think: what do I do with the time I used to devote to work? “It’s so beaten into us that we have to be productive,” says Ms Jaffe. “I've seen so many memes that are like, ‘if you haven’t written a novel in lockdown, [you’re] doing it wrong’.”

Among the affluent, work used to be something done by others, yet there have long been philosophical debates about whether it could be enjoyable. In the 1800s, Ms Jaffe points out in her book, the British designer and social campaigner William Morris pitched “three hopes” about work: “hope of rest, hope of product, hope of pleasure in the work itself”.

The decline of industrial jobs in the west, and the rise of the service economy, emphasised working for love. Nursing, food service and home healthcare, “draw on skills presumed to come naturally to women; they are seen as extensions of the caring work they are expected to do for their families”, Ms Jaffe writes. Among white-collar workers, the fetishisation of long hours in the late 1980s and 90s was accompanied by an individualistic capitalism. For many industries — notably, media — the idea of work as a form of self-actualisation intensified as security decreased.

Ms Jaffe says that there are overlapping experiences shared by those in the service sector who sit behind desks and those who stand on their feet all day. For example, the notion of the workplace as a family is a refrain in offices but it is most explicit for nannies. In the book, she tells the story of Seally, a nanny in New York who decided to live with her employers between Mondays and Fridays when the pandemic struck — leaving her own kids at home.

Seally told Ms Jaffe that she was worried about her own kids, whether they were doing their schoolwork properly: “At least I call and say, ‘Make sure you do your work’.” But she appreciates the importance of her job. “I love my work,” she said, “because my work is the silk thread that holds society together, making all other work possible”. The pandemic has reinforced the idea that the home is also a workplace and the author wants professionals who hire domestic workers and nannies to understand that and compensate accordingly for the critical role they play in facilitating their ability to do their jobs.

Perhaps the posterchild of insecure white-collar workers are interns, who have traditionally been unpaid. (In the UK, interns are eligible for pay if they are classed as a worker.) Too often, the book argues, interns have been given meaningless work with the prospect of a contract dangled in front of them, to no avail. Working conditions can also be poor — although few are as horrifying as the North Carolina zoo intern Ms Jaffe cites in the book who was killed by an escaped lion, “whose family told reporters she died ‘following her passion’ on her fourth unpaid internship”. The conditions for interns may be set back by the pandemic as so many graduates — and older workers hoping to switch industries — fight for jobs.

Ms Jaffe steers clear of advice. This is not a book that will guide readers on finding a job worthy of their devotion, though she knows that some glib tips would boost sales. “You’re told that you should love your job. Then if you don’t love your job, there’s something wrong with you,” she says. “[The problem] won’t be solved by quitting and finding a job you like better, or a different career, or deciding to just take a job that you don’t like.”

What she hopes is that people who have a nagging sense that their “job kind of sucks, they don't love it” will realise they are not alone. But they can do something about it, for instance joining a union or pushing for fewer hours. This needs to be supported by “a societal reckoning with jobs”. Do people need, for example, 24-hour access to McDonald’s and supermarkets, she asks?

Ms Jaffe wants people to imagine a society which is not organised “emotionally and temporally” around work. As she writes in the book: “What I believe, and want you to believe, too, is that love is too big and beautiful and grand and messy and human a thing to be wasted on a temporary fact of life like work.”

Wednesday, 11 December 2019

Tuesday, 14 April 2015

A very different sort of young cricketer

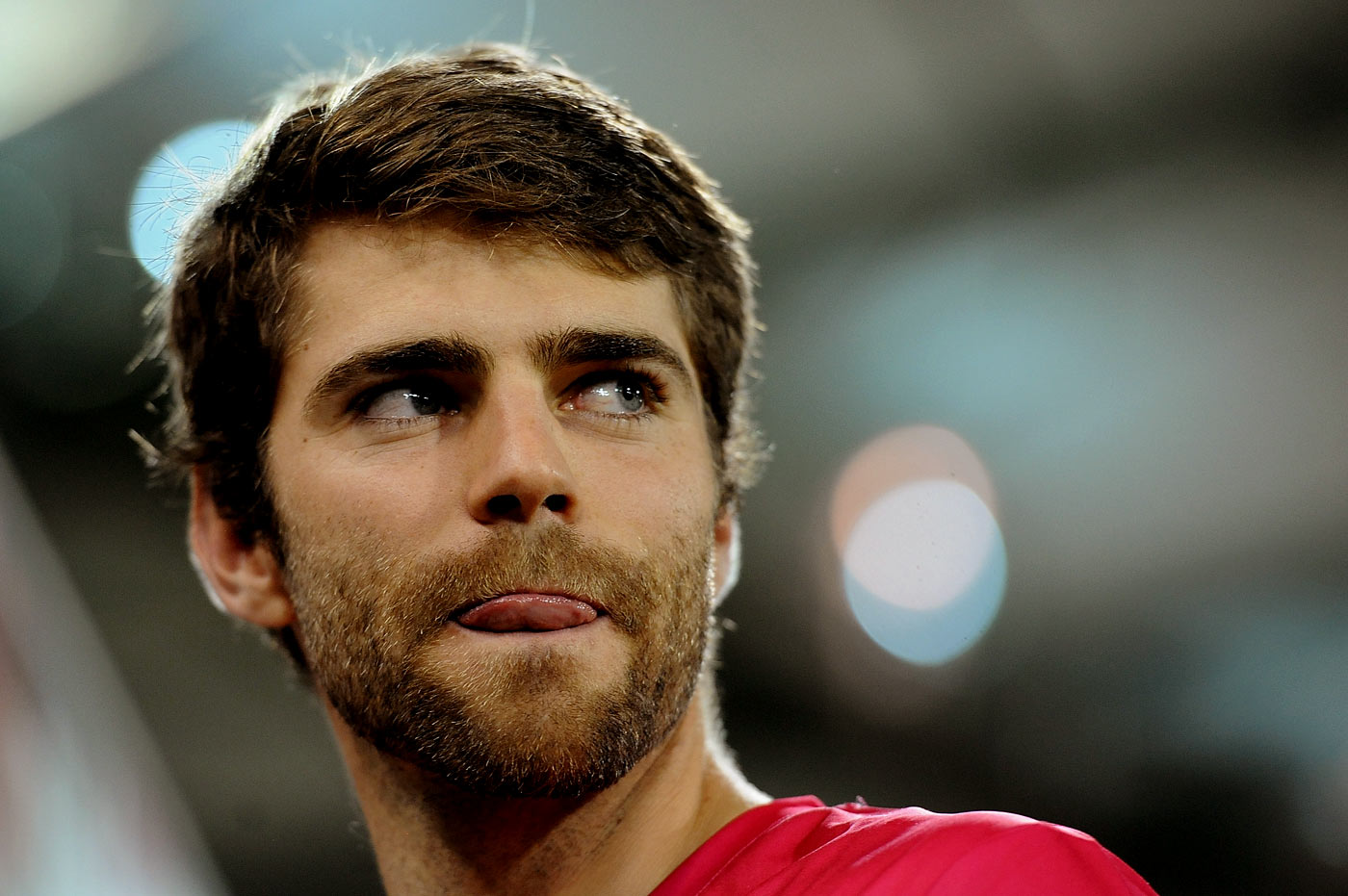

New South Wales batsman Ryan Carters reads Aldous Huxley, backpacks in Central Asia, and is passionate about helping less fortunate youngsters complete their education

Ryan Carters: majoring in economics and aiming for a Test cap © Getty Images

Ryan Carters: majoring in economics and aiming for a Test cap © Getty ImagesYou'll read plenty about Ryan Carters over the next few years. Sure, you'll read about his cricket, which continues to tick along very nicely indeed, but many of those column inches will be about Carters himself. They will present the young Australian wicketkeeper-batsman as different. Different to modern cricketers, different to the sportsmen whose macho exploits and muddled platitudes fill the back pages, different even to other "normal" young men in their mid-twenties with their normal jobs and normal interests.

And it's true. So far, Carters has had led a cricketing life less ordinary. An on-field career started in his hometown Canberra before a move to Victoria and then, when Matthew Wade's presence provided few opportunities, a swap from Melbourne to Sydney, home to Brad Haddin and Peter Nevill, Australia's first-choice glovemen.

A curious move, but one that has paid off, not behind the stumps but in front of them as an opening batsman. In New South Wales' victorious 2013-14 Sheffield Shield season, Carters managed three centuries in his 861 runs opening the batting. The season just ended was less spectacular for state and player - a third-placed finish and 448 runs at 32 - but did contain one gem of an innings, 198 against Queensland shortly before the Shield broke up for its Big Bash holidays. The guy can clearly play and, as those moves suggest, is pretty fearless.

So, off the field. Why is he different to the rest? In the course of our 45-minute chat at the SCG, we cover ground over which my professional career had not yet taken me: Aldous Huxley's experimentation with mescaline and subsequent recollections in The Doors of Perception; the culture of Central Asian countries such as Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan; and the Australian gambling culture. For the record, the first is what Carters and his book club have just finished reading, the second is where he'll spend his off season travelling and exploring, and the third is the reason he feels his charity, Batting for Change, has enjoyed success so far. It's not, to say the least, all telly and Tinder, Nando's and nightclubs.

"Dougie [Bollinger] calls me 'the philosophy major'," Carters laughs, when asked whether he is a little different to his team-mates. "Which is actually false… because I'm majoring in economics!"

Indeed, away from the field, the studies that followed his cricket from Melbourne University to Sydney after a top-of-the-class school career, the philanthropy, and love of reading place him firmly in the "bookish" category alongside - among others - his friend Eddie Cowan and Cambridge grad Mike Atherton, who famously mistook the letters "FEC" graffitied on his Lancashire locker to mean "future England captain", when in fact the second letter stood for "educated" and the first and third were as coarse as the English language can muster.

Carters on his way to 198 against Queensland in the 2014-15 Sheffield Shield © Getty Images

Carters on his way to 198 against Queensland in the 2014-15 Sheffield Shield © Getty Images"You get a few jokes about being educated," says Carters, smiling effortlessly but incessantly the whole time. "It's always been Nerds versus Julios in Australian cricket and I'm definitely on the nerds' side of that equation. I have a lot of interests that maybe aren't typical of sportsmen my age but I reckon a cricket team is basically a cross section of the different young men you encounter in society. Not everyone is some kind of jock and not everyone is from the same background."

Whatever his interests and whether they are similar to those he works with, it's clear that Carters has a pretty broad view of the world that filters into his cricket.

"Cricket provides an interesting and unusual schedule and this off season I'm going to take advantage of that. Every second week we're away playing a match interstate but now we have a load of time off. Usually I've used this period to study but this is the first time in the last five years that I've decided to get away from it all. First, I'm visiting Nepal, where Batting for Change worked last year. They're holding a tribute match to Phillip Hughes there in April [Carters' side, Team Red, won by one run], then in June and July, I'm playing club cricket for Oxford in the UK.

"But between that I'll take a month completely off the grid for the road trip through central Asia, just driving and camping. It's an important thing to do, to just reset, see where you're at away from daily demands. It's not the classic travel spot for guys our age but that's one of the reasons it appeals. We [two school friends] went to Mongolia two years ago and fell in love with that part of the world, so thought we'd try something else off the beaten track. You don't really know what you're going to encounter, which is exciting."

"I love the game, of course, but so much of my life is taken up playing and being involved in cricket that I spend more of my time outside of that doing other things rather than in the cricketing world. Watching cricket is not a chore, but is just not something I do every day. Off the field, I try to avoid thinking about the game, and I think that's a blessing.

"I'd be surprised if anyone could honestly say, 'I haven't made runs for four games but it's not affecting me psychologically', but the best I can do is get away from it for a while, re-engage with other aspects of life, come back feeling fresh and looking forward to playing cricket, as opposed to becoming consumed with it and getting stuck in that cycle of negative thinking. That's the theory behind this break, to be hungry again by September, when the Sydney Sixers have the Champions League. I reckon a break from the game will be conducive to getting the best out of myself."

As talk turns to Carters getting the best out of himself, it's impossible not to avoid Batting for Change, which this BBL season raised $102,431 for the education of young women in Mumbai, after the Sixers hit 47 sixes, with $2,179 pledged by donors for each one. A year earlier, Carters' old team, Sydney Thunder, had raised more than £30,000, used to build the three classrooms at Heartland School, Kathmandu, which Carters visited this month. These are impressive numbers but he's already looking at ways in which to expand his fundraising.

Carters (standing, third from left) with his Team Red at the Phillip Hughes' Tribute match in Kathmandu © AFP

Carters (standing, third from left) with his Team Red at the Phillip Hughes' Tribute match in Kathmandu © AFP"Last time I got away from the game, on my trip to Mongolia, I wanted to start a charity initiative to partner my cricket to promote a cause that I care deeply about and use the stage that I'm at in my career, the people that we know, to find an opportunity to reach a big section of the public. The common theme of our projects - which change annually and are linked to the LBW Trust - [Learning for a Better World] - is educating young men and women - usually at a tertiary level - who otherwise wouldn't have the opportunity, as I believe education is the way to help people out of poverty.

"I learned a lesson that if you have an idea that you're passionate about, people will jump behind it - my team-mates but also donors from around the country who have been very generous in their donations and kind in their messages of support. It's certainly making every six the Sixers hit feel that bit more special!"

Carters, evidently, is ambitious in every sense of the word; in his charity work, in his embryonic plans for life after cricket, which one senses is likely to follow philanthropic, not political (as some have suggested) lines. He's clearly a cricketer apart, but speaking of his hopes, dreams and ambitions, both as boy and man, is a reminder that he's not that different at all.

"Growing up my dreams were all cricket-based," he says, grinning again. "I played loads with my brother and Dad in the backyard and loved watching cricket and always dreamed of being a Test cricketer, like so many others in Australia. Sure, I got more interested in the world, how things work, especially as I got older; politics, economics, philosophy, reading, but cricket was the one.

"I've achieved being a pro cricketer, which is awesome, and I'd be amazed by that if you'd told me that as a 12-year-old. But the Test cricket box isn't ticked, and that - along with remembering how lucky I am and to enjoy the game - is what's driving me."

Deep down, he's just like the rest of them.

Tuesday, 15 May 2012

Moral decay? Family life's the best it's been for 1,000 years

George Monbiot

guardian.co.uk, Monday 14 May 2012 20.30 BST

'Throughout history and in virtually all human societies marriage has always been the union of a man and a woman." So says the Coalition for Marriage, whose petition against same-sex unions in the UK has so far attracted 500,000 signatures. It's a familiar claim, and it is wrong. Dozens of societies, across many centuries, have recognised same-sex marriage. In a few cases, before the 14th century, it was even celebrated in church.

This is an example of a widespread phenomenon: myth-making by cultural conservatives about past relationships. Scarcely challenged, family values campaigners have been able to construct a history that is almost entirely false.

The unbiblical and ahistorical nature of the modern Christian cult of the nuclear family is a marvel rare to behold. Those who promote it are followers of a man born out of wedlock and allegedly sired by someone other than his mother's partner. Jesus insisted that "if any man come to me, and hate not his father, and mother, and wife, and children, and brethren, and sisters … he cannot be my disciple". He issued no such injunction against homosexuality: the threat he perceived was heterosexual and familial love, which competed with the love of God.

This theme was aggressively pursued by the church for some 1,500 years. In his classic book A World of Their Own Making, Professor John Gillis points out that until the Reformation, the state of holiness was not matrimony but lifelong chastity. There were no married saints in the early medieval church. Godly families in this world were established not by men and women, united in bestial matrimony, but by the holy orders, whose members were the brothers or brides of Christ. Like most monotheistic religions (which developed among nomadic peoples), Christianity placed little value on the home. A Christian's true home belonged to another realm, and until he reached it, through death, he was considered an exile from the family of God.

The Reformation preachers created a new ideal of social organisation – the godly household – but this bore little relationship to the nuclear family. By their mid-teens, often much earlier, Gillis tells us, "virtually all young people lived and worked in another dwelling for shorter or longer periods". Across much of Europe, the majority belonged – as servants, apprentices and labourers – to houses other than those of their biological parents. The poor, by and large, did not form households; they joined them.

The father of the house, who described and treated his charges as his children, typically was unrelated to most of them. Family, prior to the 19th century, meant everyone who lived in the house. What the Reformation sanctified was the proto-industrial labour force, working and sleeping under one roof.

The belief that sex outside marriage was rare in previous centuries is also unfounded. The majority, who were too poor to marry formally, Gillis writes, "could love as they liked as long as they were discreet about it". Before the 19th century, those who intended to marry began to sleep together as soon as they had made their spousals (declared their intentions). This practice was sanctioned on the grounds that it allowed couples to discover whether or not they were compatible. If they were not, they could break it off. Premarital pregnancy was common and often uncontroversial, as long as provision was made for the children.

The nuclear family, as idealised today, was an invention of the Victorians, but it bore little relationship to the family life we are told to emulate. Its development was driven by economic rather than spiritual needs, as the industrial revolution made manufacturing in the household unviable. Much as the Victorians might extol their families, "it was simply assumed that men would have their extramarital affairs and women would also find intimacy, even passion, outside marriage" (often with other women). Gillis links the 20th-century attempt to find intimacy and passion only within marriage, and the impossible expectations this raises, to the rise in the rate of divorce.

Children's lives were characteristically wretched: farmed out to wet nurses, sometimes put to work in factories and mines, beaten, neglected, often abandoned as infants. In his book A History of Childhood, Colin Heywood reports that "the scale of abandonment in certain towns was simply staggering", reaching one third or a half of all the children born in some European cities. Street gangs of feral youths caused as much moral panic in late 19th-century England as they do today.

Conservatives often hark back to the golden age of the 1950s. But in the 1950s, John Gillis shows, people of the same persuasion believed they had suffered a great moral decline since the early 20th century. In the early 20th century, people fetishised the family lives of the Victorians. The Victorians invented this nostalgia, looking back with longing to imagined family lives before the industrial revolution.

In the Daily Telegraph today Cristina Odone maintained that "anyone who wants to improve lives in this country knows that the traditional family is key". But the tradition she invokes is imaginary. Far from this being, as cultural conservatives assert, a period of unique moral depravity, family life and the raising of children is, for most people, now surely better in the west than at any time in the past 1,000 years.

The conservatives' supposedly moral concerns turn out to be nothing but an example of the age-old custom of first idealising and then sanctifying one's own culture. The past they invoke is fabricated from their own anxieties and obsessions. It has nothing to offer us.

Wednesday, 7 March 2012

Viv Richards is 60

Sir Viv Richards: the personification of grace and menace combined

This I can see as clearly now as if it were only yesterday: pitch at Lord's, under covers for a week and more and as green as Paddy's Day, me with a new ball, and the start of a much-delayed, postponed and greatly reduced domestic limited-overs semi-final. The first delivery was spot-on, bang on length and line and, on pitching, it jagged back sharply off the seam and sank into the unprotected inside of the thigh of the batsman pushing forward.

The next was all but identical (the pitch marks, scarred on the grass, were within six inches of one another) and again the batsman came forward at it. Only this time he changed his mind midway, shifted his weight on to the back foot, and, clean as you like, thumped it with a vertical bat and high elbow not just over mid-off, or even the boundary rope, but over the corner of what is now the Compton stand and on to the Nursery. It remains the single most devastating shot I have ever seen. And Vivian Richards played a few in his time. What would he be worth today?

It is more than a year since last I saw him. Or rather he saw me, across an airport transit lounge, me en route to the Ashes, he for a tour of King and I shows with Rodney Hogg. "Hey Selve, what's happening, man?" He looked dapper, a porkpie hat perched rakishly in place of the familiar maroon cap, a little thicker round the face but still that Big Bad John "kinda broad at the shoulder and narrow at the hip" appearance that made him look as much like a top middleweight as the greatest batsman of the modern era. Even as he reaches three score years on Wednesday, he looks fighting fit.

So, from Singapore to Sydney, we supped a little and chewed the fat. There were things I wanted to ask him that I never had. Which of all the great West Indies fast bowlers of his time would he pick for his dream quartet? Andy Roberts, he said, his fellow Antiguan with an astounding cricket brain who was there at the start of it all; and the brilliant, much-lamented Malcolm Marshall. Then came Mikey, the great svelte Holding. And finally not the rumbling faithful Big Bird Joel Garner, but instead the brooding stringbean Curtly Ambrose. But, Richards admitted further, if he wanted someone to blast him a wicket, without fear, favour or consequence, there was none more chilling than Colin Croft.

Now tell me, I asked him, since it's a long time over, how do you think that bowlers – or specifically, me – should have approached the task of bowling to you. I had successes, but generally they would have been early on in an innings as he sought the upper hand and took calculated risks. Hard graft after that. You had to be aggressive, he said with some passion, aggressive. It mattered not if fast, slow or medium, spin, swing or seam, you had to demonstrate positive intent or you were shot from the start.

When, after he took guard, he wandered down the pitch, tilted his head back and, looking down his aquiline nose to eyeball the bowler, it was almost as if he was sniffing the air through his flared nostrils for the scent of fear. He wanted to feel the ball "sweet" off the bat from the off, and then he knew it was his day. Yeah aggressive, he repeated, he respected that.

But this was always easier said than done because of the way he set it up. There is an analogy with the buzz in a theatre before the curtain goes up on a great thespian. The wicket falls, but he allowed things to settle, waiting for the arena to clear, the celebrations (more muted in those days) to die down. The theatre lights dimmed and expectation became electricity. Everyone knew who was coming. And when he finally made his entrance, swaggering down the steps, cudding his gum, and windmilling his bat gently, first one arm then the other, it was a personification of grace and menace combined, the walk as unmistakable as had been that of Garry Sobers, to my mind his only rival as the finest postwar batsman of them all.

I put on a performance, he told me, it was part of my act. He wanted to dominate and the genesis of that process happened even before he closed the dressing-room door behind him. His reputation preceded him like an advance guard. It continued with the languid wicketwards saunter, the slow precision with which he took guard, the way he ambled down the pitch to tap down an imaginary mark, all the while looking for, and not always finding, eye contact with his adversary. Then he would smack the end of his bat handle with the palm of his right hand, a final intimidatory gesture.

There have been giants of the game contemporary and since, batsmen of vast pedigree and achievement: Greg Chappell, Lara, Tendulkar, Ponting, Dravid, Kallis, Sangakkara, Hayden and others. Each on his day could reduce an attack to rubble. But Richards had an aura given to no other. Truly he was scary. Happy birthday, Viv.

Wednesday, 28 September 2011

Wednesday, 24 September 2008

Anatomy of a break-up

Wednesday, 24 September 2008

It must be a trial to live with a comic and their disconcerting habits. Only comics, for example, feel such inconsolable anguish in a curry house, because they're halfway through telling a hilarious joke and it's trodden on by the waiter interrupting with "Your starters, please" and delivering your onion bhajis. Only comics come away from a funeral feeling numb and hollow because another comic's story about the dead person got a bigger laugh than their own. So my partner would probably have been able to make a case that if you're going through a period of manic volatile anxiety, it may not be advisable to be living with a comic.

For around 10 years, our awkward moments remained an unwelcome nuisance that we could learn to live with, like diabetes.

But then they grew, like the engine noise you know you shouldn't ignore, but do anyway until it suddenly clatters with doom. In some ways the more dramatic episodes were the most manageable. But when there was a low level of rumbling discontent, it was tempting to deal with it as a genuine argument, for example by exhaling a puff of exasperation and saying, "But you asked for custard." And that way we could descend into the world of the classic bickering couple, boiling with a sense of injustice while enunciating one word at a time with tensely bent fingers and a galloping heart, "You said turn left so I turned left."

There'd be the gruelling moments following a chilling exchange when neither of us would speak as we brushed past each other, each of us leaving a trail of unsettling frostiness.

Then a neighbour would call out "Hi, yoo-hoo, anyone there?" and my partner would suddenly abandon her scowl and cheerily discuss the latest episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Which makes you even more livid, unable to de-clench a single muscle while wanting to shout, "OY. We're supposed to be GRUMPY here. You might have been faking it for effect so you can switch it off as soon as an outsider arrives but I really fucking MEANT it er, sorry, Barbara."

Or we'd play out that dreadful scene in which you've snapped at each other with particularly malicious venom but you're not really in a position to leave the room to allow the acrimony to cool down. For example, having just been described as "a selfish shitty lump of shit", you've still got to sit next to each other for the foreseeable future because you've just turned on to the M6 at Lancaster.

From time to time we'd hold a series of informal summits, after the children went to bed, involving discussions that went on until about one in the morning, so that each session was probably longer than the United Nations take to discuss the crisis in Kashmir. And because I fidget, I'd make things worse by getting up to change the CD, which must be exasperating if you're midway through a heartfelt soliloquy about feeling unappreciated.

At one point my partner and I were referred to a doctor who might be able to help us out, but he couldn't find the key to his office so we conducted our discussion sitting in the corridor as hobbling men and kids with broken arms walked past us. Without looking at either of us he muttered, "Hmm, it may be depression" in a way that suggested that if you'd complained about chest pains he'd say, "Ahh, the problem is you've got an illness." After 10 minutes of questions like "What makes you angry?", he took me to one side and said, "Do you have sex?"

"Now and then," I told him hesitantly. "Try to give her more sex," he said, then walked off. And I got the impression he'd prescribe a similar remedy for food poisoning or bee stings.

One problem when a relationship is fraying is that the words that come out are difficult to decipher, as both parties find it hard to articulate the underlying cause of their anxiety. I'd hear, "The PROBLEM, as you well know, is what you KNOW it is and if you can't even KNOW what you've done, well then DON'T you think I don't KNOW." This is a delicate situation for anyone, but a comic has the overpowering instinct to say something like "That's the question for your philosophy exam you may turn over your papers and begin NOW." Which, I can testify, doesn't help.

Trying to answer the points raised, with however much sympathy, is just as useless because such anguish has its own language.

Reassuring someone that you haven't done what they're crying you've done is worthless, because that's not what they're really crying about. It even makes them more frustrated, like when you present a yelling toddler with a bottle of milk when they really want their teddy but can't say the word.

If there was an immediate solution, I couldn't find it, so I entered one of the most negative phases of life in which, despite having a house, a partner, children and middle-aged respectability, you find yourself sleeping every night on the settee. The question for any couple reduced to long-term settee status is how much bitterness must there be to make the settee preferable to the bed?

Settees are uncomfortable. You sleep at best fitfully and every morning a different bit of you is crunched and twisted. You wouldn't choose to sleep there when there's a specially designed piece of sleeping apparatus a few feet away, just because you'd had a row or were in a sulk. You'd have to feel as if you were two North Poles on a magnet, so that even if you were pushed into the bed, you'd ping backwards, twizzle round and land on the settee.

And somehow you get used to it, the journey from overwhelming love and passion to repulsion happening in such gradual increments that you accept it as normal.

I realised my life was in trouble when I started envying couples who had normal ferocious rows. They would be sitting opposite each other on a train, he fuming ahead, lips tight together, breathing heavily through his nose, while she turned each page of a magazine with a violent flick as if swatting away a strange green insect, when without looking up she would snarl, "I can't believe you're going to Dublin on my mum's sixtieth, Sean, you bastard." He'd give it two more snorts and a fume and splutter, "He's my mate, right." And I'd think, "Aah, how sweet." Because my rows had no logic and no plot. If anyone had overheard them, they'd have complained "I didn't enjoy that, there was no beginning, middle or end." They'd get going with an abstract complaint, such as "Oh yes, that's TYPICAL" and move rapidly on to random complaints such as "How DARE you? You couldn't even stand my CAT."

And yet to leave altogether seemed an awful, unimaginable prospect at every level from trying to calm inconsolable kids to having to set up a new broadband account. There's the stench of chaos: legal documents, financial agreements, access arrangements, finding somewhere to live, buying a new settee. And the dreadful finality and acceptance of failure. Despite the high number of families that break apart, each one is categorised as a "failed marriage". Aligned to this sense of failure is the humiliation of giving up. You used to gaze at each other across a table splashed with takeaway curry and communicate with tiny twinkling facial expressions, affectionate puffs and grunts, and it's achingly mournful to accept it's gone. You feel it must still be there somewhere, if only you look hard enough, in the same way that you search through the house over and over again, refusing to accept you've lost your favourite jacket.

To part in your forties with children in tow is so different from doing it in your twenties with nothing more to row about than who gets the blender. All continuity will be lost for ever; in 20 years' time there will still be awkward arrangements about who goes where at Christmas and there will be no time when everyone sits together joyfully recalling the years until now. So after a few months on that settee, it took only a half-decent week without a major cacophony to convince us to give it another go. I left the settee, and everything was marvellous. We held hands on the way to the shop, and some people came for dinner, and we had the floors done up, and we saw Crystal Palace get promoted in the play-off final. But of course it wasn't really marvellous, because nothing had been repaired. We were like an old car that's packed up, but then suddenly one day for some reason when you turn the ignition splutters along again for a while.

One night, after a particularly fraught five hours, I realised the front and back doors were both hidden behind a tower of chairs, planks of wood, buckets and assorted useless objects from under the stairs. "We've barricaded you in," said my son and daughter, "because we were afraid you might leave." These are the issues that are weighed up before anyone takes the decision to finally part from their family. Around this time, the Government and opposition were both suggesting financial incentives should be offered to families who stick together, to curb the blight of broken homes. Even that, they believe, comes down to money. They really haven't got a clue.

The final moments of a failing relationship are usually pathetically ordinary. Unlike in films, where there's a last brave embrace amid the hubbub of an Italian railway station, or a drunk but eloquent liberating speech delivered to a stunned family gathering, the last words are more likely to be "I think this is your mug."

There was a minor grumble, something to do with shopping, one sunny Saturday afternoon, that I think involved cat food, delivered with the intonation Al Pacino would have used if there'd been a cat food issue in Scarface. And immediately I knew that was the end. I had no idea a few minutes earlier that we were one small-to-medium-sized snarl from termination, but when it happened I just knew. I'd run out of tolerance, and it seemed as definite and beyond my control as if I'd gone to make a cake but discovered I'd run out of flour.

"That's it," I said, surprised. Just as there must be a definite point when someone knows, absolutely knows, "I am going to try to swim the Channel" or "I am going to explode myself in a public building" and they become mentally prepared for all that their decision entails. I knew right then that I'd soon be packing records and reassuring children, contacting the gas board and telling people they couldn't get me on that number any more.

One of the weirdest moments after moving out was the first morning I woke up in the new place. Not only was it chillingly still and quiet, this was what the place was always like. Before, there had been moments of quiet when everyone else was out, but it was always a slightly anxious quiet, a brief calm to be inhaled before doors crashed open and the natural beat of childhood urgency ricocheted once more round the building. It was the quiet of a stadium before the starting gun for a sprint final. Now there was a different quiet, a permanent quiet. I could make some artificial noise by putting on the Wu-Tang Clan, but there was no organic thud-thud "Aaagh" "Get OFF" "Dad can I have a Twix" "pewaaa waaa kachakach COOL I've shot a ZOMBIE on level 2."

Another thing that is odd is not having to tell anyone where you're going. You just leave the house, and don't have to call out, "Just nipping out for some Sellotape." To start with I'd wander up the road slightly disconcerted, as if there was some procedure I hadn't been through, perhaps a form to complete when I left the house, to send to the Town Hall. Quite simply, finding yourself on your own for the first time in 13 years is lonely. And the irony with loneliness is it can make you feel that all you want to do is be alone. Then, disaster I couldn't get cable. It wasn't available in the road for some reason. Surely there was a law somewhere that said if someone is lonely cable has to be provided as a basic human right.

Once you're no longer surrounded by the everyday torment of a fractious relationship, it becomes possible to view the squabbles and conflicts from a distance. Even in the midst of wrath and fury, you realise it isn't aimed at you, it's aimed into the air somewhere, at the universe, for being a bastard of a universe. But somehow there seemed to be no way of preventing the frustration from booming and crackling us into court.

As I walked towards the court on the day, I saw her through the window of Starbucks, reading the clinical legal documents of the case. And in that image lay the potential for total despair, the triumph of cynicism. What was the point of hope or love or the tingle of expectation if it could end sitting in Starbucks amending "related" to "pertaining" with a pink marker pen? Can there really be people who stride into court for a case against their ex-partners pumped up with the craving for victory, like American wrestlers? If so you have to wonder whether they ever were in love in the first place. My own overwhelming emotion in the courtroom was bewilderment at how this happened.

How do you end up dreading a visit from the person you used to drive all night to see briefly in the morning? You don't want to spend the rest of your life looking back with disgust at every picnic and curry you shared, regretting the times of ringing in sick to spend the day in bed together, recalling festivals, boat trips, backstage passes, crazy French bars, trips to the all-night beigel shop at five in the morning, the night the Tories were kicked out, the bewildered newspaper man in the snow, as merely part of a marathon mistake.

Of course those moments were as strikingly real and electrifying as you remember them. Which is why the only true victory in this kind of court case would be one in which both of you were sentenced to stay locked in the room until you could remember, for the last time, the thrill of the first glance, the gulp at the first eye contact, the smell of the hopeful decaying function room where you first met.

However vindictive either side may appear, what most shattered couples really want, I suspect, is to smile at each other one last time and mean it, and in that moment salvage all the memories of hope.