'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label grammar. Show all posts

Showing posts with label grammar. Show all posts

Wednesday, 17 January 2024

Friday, 23 December 2022

Monday, 26 July 2021

Sunday, 15 September 2019

Never mind ‘tax raids’, Labour – just abolish private education

As drivers of inequality, private schools are at the heart of Britain’s problems. Labour must be bold and radical on this writes Owen Jones in The Guardian

No grammar schools, lots of play: the secrets of Europe’s top education system

Unless this rotten system is abolished, Britain will never be free of social and political turmoil. It is therefore welcome – overdue, in fact – to read the Daily Telegraph’s horrified front-page story: “Corbyn tax raid on private schools”.

The segregation of children by the bank balances of their parents is integral to the class system, and the Labour Against Private Schools group has been leading an energetic campaign to shift the party’s position. The party is looking at scrapping the tax subsidies enjoyed by private education, which are de facto public subsidies for class privilege: moves such as ending VAT exemptions for school fees, as well as making private schools pay the rates other businesses are expected to. If the class system has an unofficial motto, it is “one rule for us, and one rule for everybody else”. Private schools encapsulate that, and forcing these gilded institutions to stand on their own two feet should be a bare minimum.

More radically, Labour is debating whether to commit to abolishing private education. This is exactly what the party should do, even if it is via the “slow and painless euthanasia” advocated by Robert Verkaik, the author of Posh Boys: How English Public Schools Ruin Britain. Compelling private schools to apply by the same VAT and business rate rules as others will starve them of funds, forcing many of them out of business.

Private education is, in part, a con: past OECD research has suggested that there is not “much of a performance difference” between state and private schools when socio-economic background is factored in. In other words, children from richer backgrounds – because the odds are stacked in their favour from their very conception – tend to do well, whichever school they’re sent to. However unpalatable it is for some to hear it, many well-to-do parents send their offspring to private schools because they fear them mixing with the children of the poor. Private schools do confer other advantages, of course: whether it be networks, or a sense of confidence that can shade into a poisonous sense of social superiority.

Mixing together is good for children from different backgrounds: the evidence suggests that the “cultural capital” of pupils with more privileged, university-educated parents rubs off on poorer peers without their own academic progress suffering. Such mixing creates more well-rounded human beings, breaking down social barriers. If sharp-elbowed parents are no longer able to buy themselves out of state education, they are incentivised to improve their local schools.

Look at Finland: it has almost no private or grammar schools, and instead provides a high-quality local state school for every pupil, and its education system is among the best performing on Earth. It shows why Labour should be more radical still: not least committing to abolishing grammar schools, which take in far fewer pupils who are eligible for free school meals.

Other radical measures are necessary too. Poverty damages the educational potential of children, whether through stress or poor diet, while overcrowded, poor-quality housing has the same impact too. Gaps in vocabulary open up an early age, underlining the need for early intervention. The educational expert Melissa Benn recommends that, rather than emulating the often narrow curriculums of private schools, there should be a move by state schools away from exam results: a wrap-around qualification could include a personal project, community work and a broader array of subjects.

In the coming election, Labour has to be more radical and ambitious than it was 2017. At the very core of its new manifesto must be a determination to overcome a class system that is a ceaseless engine of misery, insecurity and injustice.

Britain is a playground for the rich, but this is not a fact of life – and a commitment to ending private education will send a strong message that time has finally been called on a rotten class system.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn at the TUC Congress in Brighton. Photograph: Ben Stansall/AFP/Getty Images

The British class system is an organised racket. It concentrates wealth and power in the hands of the few, while 14 million Britons languish in poverty.

If you are dim but have rich parents, a life of comfort, affluence and power is almost inevitable – while the bright but poor are systematically robbed of their potential. The well-to-do are all but guaranteed places at the top table of the media, law, politics, medicine, military, civil service and arts. As inequality grows, so too does the stranglehold of the rich over democracy. The wealthiest 1,000 can double their fortunes in the aftermath of financial calamity, while workers suffer the worst squeeze in wages since the Napoleonic wars. State support is lavished on rich vested interests – such as the banks responsible for Britain’s economic turmoil – but stripped from disabled and low-paid people. The powerful have less stressful lives, and the prosperous are healthier, expecting to live a decade longer than those living in the most deprived areas.

The British class system is an organised racket. It concentrates wealth and power in the hands of the few, while 14 million Britons languish in poverty.

If you are dim but have rich parents, a life of comfort, affluence and power is almost inevitable – while the bright but poor are systematically robbed of their potential. The well-to-do are all but guaranteed places at the top table of the media, law, politics, medicine, military, civil service and arts. As inequality grows, so too does the stranglehold of the rich over democracy. The wealthiest 1,000 can double their fortunes in the aftermath of financial calamity, while workers suffer the worst squeeze in wages since the Napoleonic wars. State support is lavished on rich vested interests – such as the banks responsible for Britain’s economic turmoil – but stripped from disabled and low-paid people. The powerful have less stressful lives, and the prosperous are healthier, expecting to live a decade longer than those living in the most deprived areas.

No grammar schools, lots of play: the secrets of Europe’s top education system

Unless this rotten system is abolished, Britain will never be free of social and political turmoil. It is therefore welcome – overdue, in fact – to read the Daily Telegraph’s horrified front-page story: “Corbyn tax raid on private schools”.

The segregation of children by the bank balances of their parents is integral to the class system, and the Labour Against Private Schools group has been leading an energetic campaign to shift the party’s position. The party is looking at scrapping the tax subsidies enjoyed by private education, which are de facto public subsidies for class privilege: moves such as ending VAT exemptions for school fees, as well as making private schools pay the rates other businesses are expected to. If the class system has an unofficial motto, it is “one rule for us, and one rule for everybody else”. Private schools encapsulate that, and forcing these gilded institutions to stand on their own two feet should be a bare minimum.

More radically, Labour is debating whether to commit to abolishing private education. This is exactly what the party should do, even if it is via the “slow and painless euthanasia” advocated by Robert Verkaik, the author of Posh Boys: How English Public Schools Ruin Britain. Compelling private schools to apply by the same VAT and business rate rules as others will starve them of funds, forcing many of them out of business.

Private education is, in part, a con: past OECD research has suggested that there is not “much of a performance difference” between state and private schools when socio-economic background is factored in. In other words, children from richer backgrounds – because the odds are stacked in their favour from their very conception – tend to do well, whichever school they’re sent to. However unpalatable it is for some to hear it, many well-to-do parents send their offspring to private schools because they fear them mixing with the children of the poor. Private schools do confer other advantages, of course: whether it be networks, or a sense of confidence that can shade into a poisonous sense of social superiority.

Mixing together is good for children from different backgrounds: the evidence suggests that the “cultural capital” of pupils with more privileged, university-educated parents rubs off on poorer peers without their own academic progress suffering. Such mixing creates more well-rounded human beings, breaking down social barriers. If sharp-elbowed parents are no longer able to buy themselves out of state education, they are incentivised to improve their local schools.

Look at Finland: it has almost no private or grammar schools, and instead provides a high-quality local state school for every pupil, and its education system is among the best performing on Earth. It shows why Labour should be more radical still: not least committing to abolishing grammar schools, which take in far fewer pupils who are eligible for free school meals.

Other radical measures are necessary too. Poverty damages the educational potential of children, whether through stress or poor diet, while overcrowded, poor-quality housing has the same impact too. Gaps in vocabulary open up an early age, underlining the need for early intervention. The educational expert Melissa Benn recommends that, rather than emulating the often narrow curriculums of private schools, there should be a move by state schools away from exam results: a wrap-around qualification could include a personal project, community work and a broader array of subjects.

In the coming election, Labour has to be more radical and ambitious than it was 2017. At the very core of its new manifesto must be a determination to overcome a class system that is a ceaseless engine of misery, insecurity and injustice.

Britain is a playground for the rich, but this is not a fact of life – and a commitment to ending private education will send a strong message that time has finally been called on a rotten class system.

Sunday, 3 September 2017

Monday, 20 March 2017

Meritocracy: the great delusion that ingrains inequality

Jo Littler in The Guardian

We must create a level playing field for American companies and workers!” shouted Donald Trump in his first address to Congress last month, before announcing that tighter immigration controls would take the form of a “merit-based” system.

Like so many before him, Trump was wrapping political reforms in the language of meritocracy, conjuring up the image of a “fair” system where people are free to work hard to activate their talent and climb the ladder of success.

Since becoming prime minister, Theresa May has also promised to make Britain “the world’s great meritocracy” (or, in The Sun’s phrase, a “Mayritocracy”). She reiterated this pledge when announcing her revival of the grammar schools system, abandoned in the 1960s. “I want Britain to be a place where advantage is based on merit not privilege,” she proclaimed, “where it’s your talent and hard work that matter, not where you were born, who your parents are or what your accent sounds like.”

In the wake of the 2008 financial crash, many people noticed that the meritocracy they had been taught to believe in wasn’t working. The idea you could be anything you wanted to be, if only you tried hard enough, was increasingly hard to swallow. Even for the relatively pampered middle classes, jobs had dried up, become downgraded and over-pressured, debt had soared and housing was increasingly unaffordable.

Even Thatcher presented herself as an enemy of vested interests and a promoter of social mobility

This social context, created through 40 years of neoliberalism, was reflected on TV: in Breaking Bad, being brilliant at chemistry was not enough to guarantee mainstream career progression or even survival; the evisceration of social support was the backdrop to The Wire; and the precarious creative labour depicted in Girls was very different to the glamorous stability shown a decade earlier in Sex and the City.

In the face of this instability, May and Trump have managed to resuscitate the idea of meritocracy to justify policies that will increase inequality. They use different cultural accents: Trump’s brash rhetoric panders overtly to racism and misogyny; May presents herself as a fair-minded headmistress of the home counties. But their political logic is intertwined, as indicated by the indecent haste with which May rushed to the White House post-election. Both acknowledge inequality but prescribe meritocracy, capitalism and nationalism as the solution. Both want to create economic havens for the uber-rich while deepening the marketisation of public welfare systems and extending the logic of competition in everyday life.

When the word meritocracy made its first recorded appearance, in 1956 in the obscure British journal Socialist Commentary, it was a term of abuse, describing a ludicrously unequal state that surely no one would want to live in. Why, mused the industrial sociologist Alan Fox, would you want to give more prizes to the already prodigiously gifted? Instead, he argued, we should think about “cross-grading”: how to give those doing difficult or unattractive jobs more leisure time, and share out wealth more equitably so we all have a better quality of life and a happier society.

‘May and Trump have managed to resuscitate the idea of meritocracy to justify policies that will increase inequality.’ Photograph: Stefan Rousseau/PA

The philosopher Hannah Arendt agreed, arguing in a 1958 essay: “Meritocracy contradicts the principle of equality … no less than any other oligarchy.” She was particularly disparaging about the UK’s introduction of grammar schools and its institutional segregation of children according to one narrow measure of “ability”. This subject also troubled the social democratic polymath Michael Young, whose 1958 bestseller The Rise of the Meritocracy used the M-word in an affably disparaging fashion. The first half of his book outlined the rise of democracy; the second told the story of a dystopian, meritocratic future complete with black market trade in brainy babies.

But in 1972, Young’s friend the American sociologist Daniel Bell gave the concept a more positive spin when he suggested that meritocracy might actually be a productive engine for the new “knowledge economy”. By the 1980s the word was being used approvingly by a range of new-right thinktanks to describe their version of a world of extreme income difference and high social mobility. The word meritocracy had flipped in meaning.

Over the past few decades, neoliberal meritocracy has been characterised by two key features. First, the sheer scale of its attempt to extend entrepreneurial competition into the nooks and crannies of everyday life. Second, the power it has gathered by drawing from 20th-century movements for equality. Meritocracy has been presented as a means of breaking down established hierarchies of privilege.

Even Margaret Thatcher, despite her social conservatism, presented herself as an enemy of vested interests and a promoter of social mobility. Under New Labour, meritocracy embraced social liberalism, rejecting homophobia, sexism and racism. Now, we were told, really anyone could “make it”.

Those who did “make it” – the enterprising mumpreneur, the black vlogger, the council estate boy-turned-CEO – were spotlighted as parables of progress. But climbing up the social ladder became an increasing individualised matter, and as the rich got richer the ladders became longer. Those who didn’t make it were ignored or positioned as having personally failed. Under the coalition and Conservative governments, meritocratic yearning took a more punitive turn. In David Cameron’s “aspiration nation”, you were either a striver or a skiver; the very act of hoping to reach upwards became a moral obligation. Those who could not draw on existing reservoirs of privilege were told to worker harder to catch up.

The fact is, meritocracy is a myth. Social systems that reward through wealth, and which increase inequality, don’t aid social mobility, and people pass on their privilege to their children. The Conservatives have made this situation far worse by raising the inheritance tax threshold. And their reintroduction of grammar schools would involve using extremely narrow educational measures to divide children and to privilege the already privileged (often with the help of expensive private tutors). As the geographer Danny Dorling has said, it is a system of “educational apartheid”.

“Merit” itself, moreover, is a malleable, easily manipulated term. The American scholar Lani Guinier has shown how, in the 1920s, Harvard University curbed the number of Jewish students admitted by stipulating a new form of “merit”: that of “well-rounded character”. A more recent example was supplied by the reality TV filmmaking contest Project Greenlight, in which the white actor Matt Damon repeatedly interrupted black producer Effie Brown to tell her that diversity wasn’t important in film production: decisions, he explained, have to be “based entirely on merit”. This “Damonsplaining” was widely ridiculed on social media (“Can Matt Damon tell me why the caged bird sings?”). But it illustrated how versions of “merit” can be used to ingrain privilege – unlike clear criteria for specific roles, combined with anti-discrimination policies.

It is not hard to see why people find the idea of meritocracy appealing: it carries with it the idea of moving beyond where you start in life, of creative flourishing and fairness. But all the evidence shows it is a smokescreen for inequality. As Trump, May and their supporters attempt to resurrect it, there has never been a better moment to bury meritocracy for ever.

We must create a level playing field for American companies and workers!” shouted Donald Trump in his first address to Congress last month, before announcing that tighter immigration controls would take the form of a “merit-based” system.

Like so many before him, Trump was wrapping political reforms in the language of meritocracy, conjuring up the image of a “fair” system where people are free to work hard to activate their talent and climb the ladder of success.

Since becoming prime minister, Theresa May has also promised to make Britain “the world’s great meritocracy” (or, in The Sun’s phrase, a “Mayritocracy”). She reiterated this pledge when announcing her revival of the grammar schools system, abandoned in the 1960s. “I want Britain to be a place where advantage is based on merit not privilege,” she proclaimed, “where it’s your talent and hard work that matter, not where you were born, who your parents are or what your accent sounds like.”

In the wake of the 2008 financial crash, many people noticed that the meritocracy they had been taught to believe in wasn’t working. The idea you could be anything you wanted to be, if only you tried hard enough, was increasingly hard to swallow. Even for the relatively pampered middle classes, jobs had dried up, become downgraded and over-pressured, debt had soared and housing was increasingly unaffordable.

Even Thatcher presented herself as an enemy of vested interests and a promoter of social mobility

This social context, created through 40 years of neoliberalism, was reflected on TV: in Breaking Bad, being brilliant at chemistry was not enough to guarantee mainstream career progression or even survival; the evisceration of social support was the backdrop to The Wire; and the precarious creative labour depicted in Girls was very different to the glamorous stability shown a decade earlier in Sex and the City.

In the face of this instability, May and Trump have managed to resuscitate the idea of meritocracy to justify policies that will increase inequality. They use different cultural accents: Trump’s brash rhetoric panders overtly to racism and misogyny; May presents herself as a fair-minded headmistress of the home counties. But their political logic is intertwined, as indicated by the indecent haste with which May rushed to the White House post-election. Both acknowledge inequality but prescribe meritocracy, capitalism and nationalism as the solution. Both want to create economic havens for the uber-rich while deepening the marketisation of public welfare systems and extending the logic of competition in everyday life.

When the word meritocracy made its first recorded appearance, in 1956 in the obscure British journal Socialist Commentary, it was a term of abuse, describing a ludicrously unequal state that surely no one would want to live in. Why, mused the industrial sociologist Alan Fox, would you want to give more prizes to the already prodigiously gifted? Instead, he argued, we should think about “cross-grading”: how to give those doing difficult or unattractive jobs more leisure time, and share out wealth more equitably so we all have a better quality of life and a happier society.

‘May and Trump have managed to resuscitate the idea of meritocracy to justify policies that will increase inequality.’ Photograph: Stefan Rousseau/PA

The philosopher Hannah Arendt agreed, arguing in a 1958 essay: “Meritocracy contradicts the principle of equality … no less than any other oligarchy.” She was particularly disparaging about the UK’s introduction of grammar schools and its institutional segregation of children according to one narrow measure of “ability”. This subject also troubled the social democratic polymath Michael Young, whose 1958 bestseller The Rise of the Meritocracy used the M-word in an affably disparaging fashion. The first half of his book outlined the rise of democracy; the second told the story of a dystopian, meritocratic future complete with black market trade in brainy babies.

But in 1972, Young’s friend the American sociologist Daniel Bell gave the concept a more positive spin when he suggested that meritocracy might actually be a productive engine for the new “knowledge economy”. By the 1980s the word was being used approvingly by a range of new-right thinktanks to describe their version of a world of extreme income difference and high social mobility. The word meritocracy had flipped in meaning.

Over the past few decades, neoliberal meritocracy has been characterised by two key features. First, the sheer scale of its attempt to extend entrepreneurial competition into the nooks and crannies of everyday life. Second, the power it has gathered by drawing from 20th-century movements for equality. Meritocracy has been presented as a means of breaking down established hierarchies of privilege.

Even Margaret Thatcher, despite her social conservatism, presented herself as an enemy of vested interests and a promoter of social mobility. Under New Labour, meritocracy embraced social liberalism, rejecting homophobia, sexism and racism. Now, we were told, really anyone could “make it”.

Those who did “make it” – the enterprising mumpreneur, the black vlogger, the council estate boy-turned-CEO – were spotlighted as parables of progress. But climbing up the social ladder became an increasing individualised matter, and as the rich got richer the ladders became longer. Those who didn’t make it were ignored or positioned as having personally failed. Under the coalition and Conservative governments, meritocratic yearning took a more punitive turn. In David Cameron’s “aspiration nation”, you were either a striver or a skiver; the very act of hoping to reach upwards became a moral obligation. Those who could not draw on existing reservoirs of privilege were told to worker harder to catch up.

The fact is, meritocracy is a myth. Social systems that reward through wealth, and which increase inequality, don’t aid social mobility, and people pass on their privilege to their children. The Conservatives have made this situation far worse by raising the inheritance tax threshold. And their reintroduction of grammar schools would involve using extremely narrow educational measures to divide children and to privilege the already privileged (often with the help of expensive private tutors). As the geographer Danny Dorling has said, it is a system of “educational apartheid”.

“Merit” itself, moreover, is a malleable, easily manipulated term. The American scholar Lani Guinier has shown how, in the 1920s, Harvard University curbed the number of Jewish students admitted by stipulating a new form of “merit”: that of “well-rounded character”. A more recent example was supplied by the reality TV filmmaking contest Project Greenlight, in which the white actor Matt Damon repeatedly interrupted black producer Effie Brown to tell her that diversity wasn’t important in film production: decisions, he explained, have to be “based entirely on merit”. This “Damonsplaining” was widely ridiculed on social media (“Can Matt Damon tell me why the caged bird sings?”). But it illustrated how versions of “merit” can be used to ingrain privilege – unlike clear criteria for specific roles, combined with anti-discrimination policies.

It is not hard to see why people find the idea of meritocracy appealing: it carries with it the idea of moving beyond where you start in life, of creative flourishing and fairness. But all the evidence shows it is a smokescreen for inequality. As Trump, May and their supporters attempt to resurrect it, there has never been a better moment to bury meritocracy for ever.

Thursday, 16 March 2017

Oxford comma helps drivers win dispute about overtime pay

Elena Cresci in The Guardian

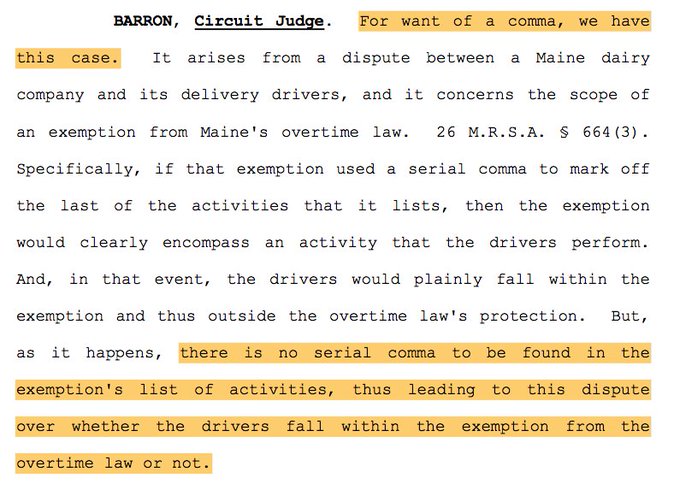

Never let it be said that punctuation doesn’t matter.

In Maine, the much-disputed Oxford comma has helped a group of dairy drivers in a dispute with a company about overtime pay.

The Oxford comma is used before the words “and” or “or” in a list of three or more things. Also known as the serial comma, its aficionados say it clarifies sentences in which things are listed.

As Grammarly notes, the sentences “I love my parents, Lady Gaga and Humpty Dumpty” and “I love my parents, Lady Gaga, and Humpty Dumpty” are a little different. Without a comma, it looks like the parents in question are, in fact, Lady Gaga and Humpty Dumpty.

on the one hand I love the #oxfordcomma, on the other hand these sentences truly are SO GOOD

In a judgment that will delight Oxford comma enthusiasts everywhere, a US court of appeals sided with delivery drivers for Oakhurst Dairy because the lack of a comma made part of Maine’s overtime laws too ambiguous.

United States Court of Appeals

For the First Circuit, No. 16-1901 (March 13, 2017), Judge Barron:

The Oxford Comma is important.

The state’s law says the following activities do not count for overtime pay:

The canning, processing, preserving, freezing, drying, marketing, storing, packing for shipment or distribution of:(1) Agricultural produce;

(2) Meat and fish products; and

(3) Perishable foods.

The drivers argued, due to a lack of a comma between “packing for shipment” and “or distribution”, the law refers to the single activity of “packing”, not to “packing” and “distribution” as two separate activities. As the drivers distribute – but do not pack – the goods, this would make them eligible for overtime pay.

Previously, a district court had ruled in the dairy company’s favour, who argued that the legislation “unambiguously” identified the two as separate activities exempt from overtime pay. But the appeals judge sided with the drivers.

We conclude that the exemption’s scope is actually not so clear in this regard. And because, under Maine law, ambiguities in the state’s wage and hour laws must be construed liberally in order to accomplish their remedial purpose, we adopt the drivers’ narrower reading of the exemption.

AP style fans, we know you'll appreciate an #APStyleHaiku about Oxford commas. You can write, count and share, too. https://twitter.com/nathanfrontiero/status/753708777862418432 …

The Oxford comma ignites considerable passion among its proponents and opponents. In 2011, when it was wrongly reported that the Oxford comma was being dropped by the University of Oxford style guide, there was uproar.

“Who gives a fuck about an Oxford comma?” opens one Vampire Weekend song.

The Guardian style guide has the following to say about Oxford commas:

a comma before the final “and” in lists: straightforward ones (he ate ham, eggs and chips) do not need one, but sometimes it can help the reader (he ate cereal, kippers, bacon, eggs, toast and marmalade, and tea).Sometimes it is essential: compareI dedicate this book to my parents, Martin Amis, and JK RowlingwithI dedicate this book to my parents, Martin Amis and JK Rowling

Sunday, 16 October 2016

Just 2.6% of grammar school pupils are from poor backgrounds

Daniel Boffey in The Guardian

Just 3,100 of the 117,000 pupils who currently attend grammar schools come from families poor enough to be eligible for free school meals.

The proportion of students (2.6%) is lower than previously reported, and was last night seized upon by critics of the government’s plans for more selection in the state system.

The average proportion of pupils entitled to free school meals in areas that currently select on academic ability is thought to be around 18%.

Lucy Powell, the former shadow education secretary, said the figures, compiled by the House of Commons library from Department for Education records from January this year, illustrated how selection was failing those from the least affluent backgrounds.

“Grammar schools have a shamefully low record when it comes to the number of children from poor backgrounds attending them,” said Powell.

Ofsted chief slams Theresa May’s ‘obsession’ with grammar schools

The government’s green paper on education reform proposes that existing grammar schools should be allowed to expand and new ones be allowed to open, while existing comprehensives could opt to be selective. It also proposes encouraging multi-academy trusts to select within their family of schools, in order to set up “centres of excellence” for their most able students.

But Powell said there were now 23 Tory MPs who supported her campaign to force a government U-turn on their plans to introduce more selection. “All the evidence shows that selective education creates barriers for disadvantaged children rather than breaking them down,” she said. “These figures tell the real story. A minuscule number of children on free school meals pass the 11-plus.

“That these tiny, tiny few do well is no measure. The measure should be how can we ensure that every child gets an excellent academic education.

“Rather than serving a privileged few, ministers should focus on tackling real disadvantage and ensure that all schools have enough teachers and resources to deliver a world class education for all – things that are in serious trouble right now.”

The government’s policy was nevertheless given a boost last week when new “value-added figures” suggested that the 163 grammar schools in England had better progress scores across all attainment levels than the other 2,800 state secondaries, achieving about a third of a GCSE grade higher than pupils with the same prior results at other schools. The new “Progress 8 measures” record pupils’ progress across eight subjects from age 11 to 16.

Education secretary Justine Greening said the statistics gave the government “even more reason to make more of these good school places available in more areas”.

Rebecca Allen, director of Education Datalab and an expert in the analysis of large scale administrative and survey datasets, warned that ministers should be cautious in latching on to “crude” performance tests. Allen said that the Key Stage 2 scores used to test the progress of pupils in the years up to their GCSEs was a poor indicator of academic potential, as indicated by the fact that many with low scores passed the 11-plus.

She said that it would be better to examine progress across the board in local authorities that are selective. Those results show a marginally positive set of results in terms of progress of all pupils.

However, Allen said that even then the potential of a cohort of pupils in areas where grammars exist may well be higher in the first place because pupils could have been drawn from outside the area, distorting any analysis on a local authority by local authority basis.

Allen added that the statistics also did not take into account the distorting effect on the figures produced by those who would have otherwise stayed in private education who have moved into state grammar schools where they are available.

“These calculations are made only for those in the state sector, yet the presence of grammar schools changes the type of pupils in private schools,” she said. “About 12 per cent of those in grammars were in the private sector at age 10 and may well have stayed there had state-selection not been available.

“Moreover, large numbers who fail the 11-plus exit the state sector for non-elite private schools. It is very hard to assess how these private sector transfers affect local authority Progress 8 figures, so we must be cautious before using crude performance table measures to make claims about policy effectiveness.”

Just 3,100 of the 117,000 pupils who currently attend grammar schools come from families poor enough to be eligible for free school meals.

----Also read

-----

The proportion of students (2.6%) is lower than previously reported, and was last night seized upon by critics of the government’s plans for more selection in the state system.

The average proportion of pupils entitled to free school meals in areas that currently select on academic ability is thought to be around 18%.

Lucy Powell, the former shadow education secretary, said the figures, compiled by the House of Commons library from Department for Education records from January this year, illustrated how selection was failing those from the least affluent backgrounds.

“Grammar schools have a shamefully low record when it comes to the number of children from poor backgrounds attending them,” said Powell.

Ofsted chief slams Theresa May’s ‘obsession’ with grammar schools

The government’s green paper on education reform proposes that existing grammar schools should be allowed to expand and new ones be allowed to open, while existing comprehensives could opt to be selective. It also proposes encouraging multi-academy trusts to select within their family of schools, in order to set up “centres of excellence” for their most able students.

But Powell said there were now 23 Tory MPs who supported her campaign to force a government U-turn on their plans to introduce more selection. “All the evidence shows that selective education creates barriers for disadvantaged children rather than breaking them down,” she said. “These figures tell the real story. A minuscule number of children on free school meals pass the 11-plus.

“That these tiny, tiny few do well is no measure. The measure should be how can we ensure that every child gets an excellent academic education.

“Rather than serving a privileged few, ministers should focus on tackling real disadvantage and ensure that all schools have enough teachers and resources to deliver a world class education for all – things that are in serious trouble right now.”

The government’s policy was nevertheless given a boost last week when new “value-added figures” suggested that the 163 grammar schools in England had better progress scores across all attainment levels than the other 2,800 state secondaries, achieving about a third of a GCSE grade higher than pupils with the same prior results at other schools. The new “Progress 8 measures” record pupils’ progress across eight subjects from age 11 to 16.

Education secretary Justine Greening said the statistics gave the government “even more reason to make more of these good school places available in more areas”.

Rebecca Allen, director of Education Datalab and an expert in the analysis of large scale administrative and survey datasets, warned that ministers should be cautious in latching on to “crude” performance tests. Allen said that the Key Stage 2 scores used to test the progress of pupils in the years up to their GCSEs was a poor indicator of academic potential, as indicated by the fact that many with low scores passed the 11-plus.

She said that it would be better to examine progress across the board in local authorities that are selective. Those results show a marginally positive set of results in terms of progress of all pupils.

However, Allen said that even then the potential of a cohort of pupils in areas where grammars exist may well be higher in the first place because pupils could have been drawn from outside the area, distorting any analysis on a local authority by local authority basis.

Allen added that the statistics also did not take into account the distorting effect on the figures produced by those who would have otherwise stayed in private education who have moved into state grammar schools where they are available.

“These calculations are made only for those in the state sector, yet the presence of grammar schools changes the type of pupils in private schools,” she said. “About 12 per cent of those in grammars were in the private sector at age 10 and may well have stayed there had state-selection not been available.

“Moreover, large numbers who fail the 11-plus exit the state sector for non-elite private schools. It is very hard to assess how these private sector transfers affect local authority Progress 8 figures, so we must be cautious before using crude performance table measures to make claims about policy effectiveness.”

Wednesday, 12 October 2016

Grammar schools are unfair. Principled parents must refuse to encourage them

Louise Tickle in The Guardian

‘A gentle challenge will often prompt the mantra that’s endlessly parroted to justify a parent’s principles turning to dust in the lead-up to the 11-plus exam. ‘You have to do the best by your child, don’t you?’’ Photograph: Rex/Shutterstock

When my son was six months old, I agreed to move to Gloucestershire. It’s lovely here in the Stroud Valleys – or it is until your child reaches the second half of primary school, and everyday chats about school stuff with friends suddenly start to veer off into shamefaced mumbles about tutoring, and how if Charlie or Clara want to take the 11-plus with their mates, “then who are we to stop them?”

You’re their parents, who make a heap of choices about your children’s lives based on your political beliefs, is my answer. So why crumble now?

As an education journalist who is opposed to selection – because it disproportionately benefits an already vastly advantaged middle-class minority, and actively harms the educational prospects of other, often poorer children – I find negotiating these conversations with people I know painfully fraught. I have not yet found a polite way to tell a friend who allows their child to take the 11-plus that, while I cling to the idea that they are not at heart a shit, they are doing an exceedingly shitty thing.

A gentle challenge will often prompt the mantra that’s endlessly parroted to justify a parent’s principles turning to dust in the lead-up to the 11-plus exam. “You have to do the best by your child, don’t you?” is intoned with a phlegmatic sigh, lips pressed together in wry acknowledgment that the situation isn’t ideal, but life’s a bitch, and one’s own child’s interests – obviously– trump every other consideration. The listener’s agreement is automatically assumed.

No, I increasingly want to yell. Given that their offspring, and pretty much all their friends, are among the luckiest children in the history of humankind, choosing to construct a more divided society via our taxpayer-funded education system that disadvantages other kids – some with unimaginably difficult home lives that make it harder for them to do well at school – is not something I think should be encouraged. But it appears to be viewed as aberrant or just plain weird by many middle-class parents not to grab every possible personal advantage and hug it tight to the family bosom, while still maintaining they want the best for all.

We’re animals. I get it. We’re programmed to chase advantage for our young, even to the detriment of other people’s children. And so while it’s particularly pernicious that some parents pay for months, sometimes years, of tutoring to get their child through an exam that they might well otherwise fail, I know it’s because they are desperate to secure for their child any extra benefit going in a country that is becoming ever more unequal.

But inside, I seethe. Often I do so silently, because with so many parents actively pursuing the advantages that selection confers, confronting them has become deeply socially uncomfortable.It’s incongruent with many people’s view of themselves as good folk who believe in fairness and equality. And facing this paradox head-on in conversation has, in my experience, become something of a taboo: how do you call out friends and stay friends, when you’re accusing them of hurting other people’s children? I try, but the discomfort it prompts is palpable, and defensiveness is rife. The fact that researchers have concluded that there is “no benefit to attending a grammar school for high-attaining pupils” makes the unedifying scrabble even more sad.

It’s the system that stinks, of course, and it has to be fought at the policy level, not by individuals at the school gates. Parents mustn’t set themselves against each other. While that is true, it doesn’t let parents off the hook. It may be possible – I guess – to be opposed to selection in principle even while sending your children to a grammar school. Yet in practice parents cannot challenge a system with any authority when they have cut the ground from beneath their own feet. When prominent people such as Shami Chakrabarti express concerns about selectionand then admit they opt out and write a fat cheque when it comes to their own kids, asking ordinary parents to stand up and be counted becomes tricky. Within the education sector too, people give up their power by acquiescing with a system they think is wrong: I know a headteacher who believes passionately in comprehensive education, whose child attends the local grammar: it is now impossible for that head to speak out without being called a hypocrite. We all make compromises in life, but this one comes at a high price paid by children who aren’t “selected” and who have no power and no say.

No unfair system was ever overturned by people carrying on using it for their own selfish ends while spouting their dismay. If the government sees parents urgently ushering their children into the 11-plus queue, then there is no debate left to win. Arguments against selection are fatally compromised when the very people one might normally expect to challenge unfairness, and who have the political heft to do it – articulate, middle-class parents – wave Charlie and Clara off to the local grammar every morning and, perfectly understandably, then feel too embarrassed to raise their voices.

‘A gentle challenge will often prompt the mantra that’s endlessly parroted to justify a parent’s principles turning to dust in the lead-up to the 11-plus exam. ‘You have to do the best by your child, don’t you?’’ Photograph: Rex/Shutterstock

When my son was six months old, I agreed to move to Gloucestershire. It’s lovely here in the Stroud Valleys – or it is until your child reaches the second half of primary school, and everyday chats about school stuff with friends suddenly start to veer off into shamefaced mumbles about tutoring, and how if Charlie or Clara want to take the 11-plus with their mates, “then who are we to stop them?”

You’re their parents, who make a heap of choices about your children’s lives based on your political beliefs, is my answer. So why crumble now?

As an education journalist who is opposed to selection – because it disproportionately benefits an already vastly advantaged middle-class minority, and actively harms the educational prospects of other, often poorer children – I find negotiating these conversations with people I know painfully fraught. I have not yet found a polite way to tell a friend who allows their child to take the 11-plus that, while I cling to the idea that they are not at heart a shit, they are doing an exceedingly shitty thing.

A gentle challenge will often prompt the mantra that’s endlessly parroted to justify a parent’s principles turning to dust in the lead-up to the 11-plus exam. “You have to do the best by your child, don’t you?” is intoned with a phlegmatic sigh, lips pressed together in wry acknowledgment that the situation isn’t ideal, but life’s a bitch, and one’s own child’s interests – obviously– trump every other consideration. The listener’s agreement is automatically assumed.

No, I increasingly want to yell. Given that their offspring, and pretty much all their friends, are among the luckiest children in the history of humankind, choosing to construct a more divided society via our taxpayer-funded education system that disadvantages other kids – some with unimaginably difficult home lives that make it harder for them to do well at school – is not something I think should be encouraged. But it appears to be viewed as aberrant or just plain weird by many middle-class parents not to grab every possible personal advantage and hug it tight to the family bosom, while still maintaining they want the best for all.

We’re animals. I get it. We’re programmed to chase advantage for our young, even to the detriment of other people’s children. And so while it’s particularly pernicious that some parents pay for months, sometimes years, of tutoring to get their child through an exam that they might well otherwise fail, I know it’s because they are desperate to secure for their child any extra benefit going in a country that is becoming ever more unequal.

But inside, I seethe. Often I do so silently, because with so many parents actively pursuing the advantages that selection confers, confronting them has become deeply socially uncomfortable.It’s incongruent with many people’s view of themselves as good folk who believe in fairness and equality. And facing this paradox head-on in conversation has, in my experience, become something of a taboo: how do you call out friends and stay friends, when you’re accusing them of hurting other people’s children? I try, but the discomfort it prompts is palpable, and defensiveness is rife. The fact that researchers have concluded that there is “no benefit to attending a grammar school for high-attaining pupils” makes the unedifying scrabble even more sad.

It’s the system that stinks, of course, and it has to be fought at the policy level, not by individuals at the school gates. Parents mustn’t set themselves against each other. While that is true, it doesn’t let parents off the hook. It may be possible – I guess – to be opposed to selection in principle even while sending your children to a grammar school. Yet in practice parents cannot challenge a system with any authority when they have cut the ground from beneath their own feet. When prominent people such as Shami Chakrabarti express concerns about selectionand then admit they opt out and write a fat cheque when it comes to their own kids, asking ordinary parents to stand up and be counted becomes tricky. Within the education sector too, people give up their power by acquiescing with a system they think is wrong: I know a headteacher who believes passionately in comprehensive education, whose child attends the local grammar: it is now impossible for that head to speak out without being called a hypocrite. We all make compromises in life, but this one comes at a high price paid by children who aren’t “selected” and who have no power and no say.

No unfair system was ever overturned by people carrying on using it for their own selfish ends while spouting their dismay. If the government sees parents urgently ushering their children into the 11-plus queue, then there is no debate left to win. Arguments against selection are fatally compromised when the very people one might normally expect to challenge unfairness, and who have the political heft to do it – articulate, middle-class parents – wave Charlie and Clara off to the local grammar every morning and, perfectly understandably, then feel too embarrassed to raise their voices.

Wednesday, 30 March 2016

Are you a grammar pedant? This might be why

David Shariatmadari in The Guardian

When you picture a “grammar nazi”, what does that person look like?

Are they old or young? Male or female? Professorial or blue-collar?

A new study suggests they could be any of those things. In an experiment involving 80 Americans from a range of backgrounds, linguists Julie Boland and Robin Queen found no significant links between a judgmental attitude towards “typos” and “grammos” and gender, age or level of education.

So you can’t tell if someone hunts down misprints and writes letters to editors just by looking at them. If you know something about the way they experience the world, though, you might be able to take an educated guess.

Introverts, it turns out, are more likely to get annoyed at both typos and grammos. Not only that; they’ll probably not want to share their lives with you if you’re particularly error-prone.

Boland and Queen tested people’s reactions to emails responding to an ad for a housemate. Some of them contained typos, some grammos and some were perfectly written. They were then asked whether they agreed with statements like “the writer seems friendly”, “the writer seems considerate”, “the writer seems trustworthy”. Their ratings were combined to produce an overall “good housemate” score.

They then had to fill out questionnaires about their own personalities, based on the “big five” traits – openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism.

And that’s how the researchers found that introverts were more likely than extraverts to rate people as poor potential housemates if their spelling or grammar was bad. There were other findings – agreeable people, perhaps unsurprisingly, were easygoing when it came to grammos. Conscientious people tended to see typos as a problem. Levels of neuroticism, oddly enough, didn’t predict any kind of penchant for pet peeves.

But the finding about introversion is intriguing, because it’s harder to understand.

First, a word about what makes an introvert. It’s not the same as being shy. The following quote summarises one common view, associated with psychologist Hans Eysenck.

Eysenck’s theory was that extroverts have just a slightly lower basic rate of arousal. The effect is that they need to work a little harder to get themselves up to the level others find normal and pleasant without doing anything. Hence the need for company, seeking out novel experiences and risks. Conversely, highly introverted individuals find themselves overstimulated by things others might find merely pleasantly exciting or engaging.

I spoke to Robin Queen. “We hadn’t quite anticipated that introversion would have the effect it did,” she told me.

“I found myself asking: this is weird – why would it be the case that introverts care more?”

Queen isn’t an expert in the study of personality – she’s a linguist – but she has a hunch. “My guess is that introverts have more sensitivity to variability.” That could make variations from the norm like mistakes – which require extra processing that increases arousal – more irksome.

“Maybe there’s something about extraverts that makes them less bothered by it. Because extraverts enjoy variability and engaging with people. They find that energising. This could be an indirect manifestation of that.”

I would describe myself as an introvert (I just took two “big five” personality tests and scored 42/100 and 47/100 for extraversion, so maybe I’m more of a people-person than I thought). I’m also an editor, with more than a passing interest in language. Two forces compete within me when I see a grammo or worse. As a linguist, I know that meaning is use – so, if lots of people use “disinterested” to mean “uninterested”, well, that’s now part of its meaning. Error is the engine of language change. Error is inevitable.

But at the same time, I feel something akin to having a stone in my shoe when I see a mistake. It acts as an irritant. If I had to relate that to my introversion, then I would say a sense of order and predictability is important to me. I like it when things are under control.

I’m not sure whether that makes me a good housemate or not. But I can spot a dangling modifier a mile off.

When you picture a “grammar nazi”, what does that person look like?

Are they old or young? Male or female? Professorial or blue-collar?

A new study suggests they could be any of those things. In an experiment involving 80 Americans from a range of backgrounds, linguists Julie Boland and Robin Queen found no significant links between a judgmental attitude towards “typos” and “grammos” and gender, age or level of education.

So you can’t tell if someone hunts down misprints and writes letters to editors just by looking at them. If you know something about the way they experience the world, though, you might be able to take an educated guess.

Introverts, it turns out, are more likely to get annoyed at both typos and grammos. Not only that; they’ll probably not want to share their lives with you if you’re particularly error-prone.

Boland and Queen tested people’s reactions to emails responding to an ad for a housemate. Some of them contained typos, some grammos and some were perfectly written. They were then asked whether they agreed with statements like “the writer seems friendly”, “the writer seems considerate”, “the writer seems trustworthy”. Their ratings were combined to produce an overall “good housemate” score.

They then had to fill out questionnaires about their own personalities, based on the “big five” traits – openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism.

And that’s how the researchers found that introverts were more likely than extraverts to rate people as poor potential housemates if their spelling or grammar was bad. There were other findings – agreeable people, perhaps unsurprisingly, were easygoing when it came to grammos. Conscientious people tended to see typos as a problem. Levels of neuroticism, oddly enough, didn’t predict any kind of penchant for pet peeves.

But the finding about introversion is intriguing, because it’s harder to understand.

First, a word about what makes an introvert. It’s not the same as being shy. The following quote summarises one common view, associated with psychologist Hans Eysenck.

Eysenck’s theory was that extroverts have just a slightly lower basic rate of arousal. The effect is that they need to work a little harder to get themselves up to the level others find normal and pleasant without doing anything. Hence the need for company, seeking out novel experiences and risks. Conversely, highly introverted individuals find themselves overstimulated by things others might find merely pleasantly exciting or engaging.

I spoke to Robin Queen. “We hadn’t quite anticipated that introversion would have the effect it did,” she told me.

“I found myself asking: this is weird – why would it be the case that introverts care more?”

Queen isn’t an expert in the study of personality – she’s a linguist – but she has a hunch. “My guess is that introverts have more sensitivity to variability.” That could make variations from the norm like mistakes – which require extra processing that increases arousal – more irksome.

“Maybe there’s something about extraverts that makes them less bothered by it. Because extraverts enjoy variability and engaging with people. They find that energising. This could be an indirect manifestation of that.”

I would describe myself as an introvert (I just took two “big five” personality tests and scored 42/100 and 47/100 for extraversion, so maybe I’m more of a people-person than I thought). I’m also an editor, with more than a passing interest in language. Two forces compete within me when I see a grammo or worse. As a linguist, I know that meaning is use – so, if lots of people use “disinterested” to mean “uninterested”, well, that’s now part of its meaning. Error is the engine of language change. Error is inevitable.

But at the same time, I feel something akin to having a stone in my shoe when I see a mistake. It acts as an irritant. If I had to relate that to my introversion, then I would say a sense of order and predictability is important to me. I like it when things are under control.

I’m not sure whether that makes me a good housemate or not. But I can spot a dangling modifier a mile off.

Friday, 31 October 2014

Why are Asians under represented in English cricket?

by Girish Menon

A recent ECB survey found

that 30 % of the grass root level cricket players were of Asian origin while it

reduces dramatically to 6.2 % at the level of first class county cricketers. Why?

When this question was asked

to Moeen Ali, he opined among other things, "I also feel we lose heart too quickly. A lot of people

think it is easy to be a professional cricketer, but it is difficult. There is

a lot of sacrifice and dedication," While some may view Ali's views as

suffering from the Stockholm

syndrome, in my personal opinion it resembles the 'Lazy Japanese and Thieving

Germans' metaphor highlighted by the economist Ha Joon Chang. Hence, Ali's

views should not be confused with what in my perspective are some of the actual

reasons why there is a dearth of Asian faces in county cricket.

The

Cambridge

But

now that the economies of Japan ,

Korea and Germany

If

it wants the truth, English cricket should examine the issue raised by the

Macpherson report on 'institutional racism in the police' and ask if this is

true in county cricket as well. Immigrants, as the statistics suggest, from the

subcontinent can be found in large numbers in grassroots cricket from the time

they joined the British labour force. There are many immigrants only cricket

leagues in the UK , e.g in Bradford , where players of good talent can be found. But,

as Jass Bhamra's father mentioned in the film Bend it Like Beckham they have

not been allowed access to the system. Why, Yorkshire

waited till the 1990s to select an Asian player for the first time.

----Also read

----Also read

Failing the Tebbit test - Difficulties in supporting the England cricket team

----

Of

course, if the England

Secondly,

to make it up the ranks in English cricket it is essential to have an expensive

well connected coach. Junior county selections are based on this network and

any unorthodox talent would be weeded out at the earliest level either because

of not having a private coach or because the technique is rendered untenable as

it blots the copybook. So, many children of Asian origin from weaker economic

backgrounds are weeded out by this network.

This

is akin to the methods adopted by parents in the shires where grammar schools

exist. Hiring expensive tutors for their wards is the middle class way of

crowding out genuinely academic oriented students from weaker economic

backgrounds. Better off Asians are equally culpable in distorting the grammar school

system and its objectives.

So

what could be done. I think positive discrimination is the answer. We only need

to look at South African cricket to see what results it can bring. My

suggestion would be that every team should have two places reserved: one for a

minority player and another for an unorthodox player. This should to some

extent break up the parent-coach orthodoxy and breathe some fresh air and

dynamism into English cricket.

Personally,

I have advised my son that he should play cricket only for pleasure and not to

aspire for serious professional cricket because of the opacity in the selection

mechanism which means an uncertain economic future. He is 16, a genuine leg

spinner with little coaching but with good control on flight and turn. Often he

complains about conservative captains and coaches who were unwilling to gamble

away a few runs in the hope of getting wickets. Many years ago, when my son was

not picked by a county side, I asked the coach the reason and he said because,

'he flights the ball and is slower through the air'. With what conviction then could

I have told my lad that you can make a decent living out of cricket if you

persevere enough?

Sunday, 4 May 2014

Grammar schools must give poorer children a fair chance

The higher a family's income, the greater a pupil's chance of being admitted to a grammar. But fairer admissions will only begin to level the playing field

Pupils take a practice test during a tutoring session. 'Grammar school heads say they want to end the tutoring culture. But, with a quarter of pupils receiving private tuition, that may be wishful thinking.' Photograph: Antonio Olmos

Around half of England's 164 grammar schools plan to prioritise bright pupils from poorer families in their admissions policies. They have provoked a predictable backlash from some who see this as social engineering.

Yet the heads are right to embrace fairer admissions. And even those who would prefer all schools to be comprehensive should welcome these measures. Indeed, it is crucial that the grammars go further if they are going to play a stronger role in supporting social mobility.

Research for the Sutton Trust has shown that the number of grammar school pupils who come from outside the state sector – largely fee-paying preparatory schools – is more than four times the number eligible for free school meals. Only 6% of pupils in England go to prep schools, whereas 16% are entitled to free meals – but just 600 of the 22,000 children entering grammar schools between 2009 and 2011 were from these least advantaged homes, whereas 2,800 had been privately educated.

Of course grammar schools are selective, and many children from poorer homes have already fallen behind their better-off peers by age 11. That gap needs narrowing. Yet when our researchers looked at all pupils reaching the expected standard for a 14-year-old in the end-of-primary English and maths tests, they found that only 40% of able free-school-meal pupils gained admission to grammars, compared with 66% of other pupils.

Nor is it just poor pupils losing out. The research showed that the higher your family's income, the greater your chance of being admitted to a grammar. There is a good reason for this: parents who can afford it pay to make sure their children pass the test. For the richest parents, it will be £9,000-a-year prep school fees. For others, it will be £20 an hour or more for a private tutor. For many, these sums are more than they can afford.

That's why fairer admissions in grammar schools, far from giving less privileged pupils an unfair advantage, would simply help level the playing field. But while this is a welcome first step, more needs to be done. Admissions policies are only one part of the equation.

Grammar schools should reach out to a wider group of schools and pupils if the link between income and access is to be broken, while all primary schools in selective areas should encourage their bright pupils to apply in the first place. Admissions tests should reduce any bias that could disadvantage pupils from under-represented backgrounds.

To their credit, many grammar schools are acting here too: the Sutton Trust is working with the King Edward VI foundation in Birmingham and others to improve outreach programmes, while many schools are switching to less coachable tests.

Grammar school heads say they want to end the tutoring culture. But, with a quarter of pupils receiving private tuition, that may be wishful thinking. That's why grammar applicants should be entitled to free sessions to help familiarise them with the test, so those from low-income families don't lose out.

Critics will say that we should abolish rather than ameliorate selection. But the reality is that no major political party will scrap the remaining grammars without a groundswell of parental support: in this respect, the coalition parties and Labour are at one. So where grammars remain, it is vital that they do more to open their doors to bright children from low- and middle-income homes.

Others will say that we should focus instead on social selection in comprehensives or fee-paying independent schools. We also want to see independent day schools opened up on the basis of merit rather than money.

But grammar schools still educate one in 20 secondary pupils, and many have a good record in getting their students into our best universities. So it is crucial that they are open to bright children of all backgrounds.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)