'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label leg spin. Show all posts

Showing posts with label leg spin. Show all posts

Monday, 18 February 2019

Sunday, 25 November 2018

Sunday, 8 July 2018

Why are modern batsmen weak against legspin in the short formats?

Ian Chappell in Cricinfo

It's not only the range of strokes that has dramatically evolved in short-format batting but also the mental approach. Contrast the somnambulistic approach of Essex's Brian Ward in a 1969 40-over game with England's record-breaking assault on the Australian bowling at Trent Bridge recently.

Ward decided that Somerset offspinner Brian Langford was the danger man in the opposition attack, and eight consecutive maidens resulted, handing the bowler the never-to-be-repeated figures of 8-8-0-0. On the other hand England's batsmen this year displayed no such inhibitions in rattling up 481 off 50 overs, and Australia's bowlers, headed by Andrew Tye, with 9-0-100-0, were pummelled.

Nevertheless one thing has remained constant in the short formats: a wariness around spin bowling, although currently it's more likely to be the wrist variety than fingerspin.

The list of successful wristspinners in short-format cricket is growing rapidly and there have been some outstanding recent performances. Afghanistan's Rashid Khan was the joint leading wicket-taker in the BBL; England's Adil Rashid (along with spin-bowling companion Moeen Ali), took the most wicketsin the recent whitewash of Australia; and in successive T20Is against England, India's duo of Yuzvendra Chahal and Kuldeep Yadav have claimed the rare distinction of a five-wicket haul. It's a trail of destruction that have would gladdened the heart of Bill "Tiger" O'Reilly, a great wristspinner himself and the most insistent promoter of the art there has ever been.

Wristspinners are extremely successful in the shorter formats and are being eagerly sought after for the many T20 leagues. Their enormous success is mostly down to the deception they provide, since they are able to turn it from both leg and off with only a minimal change of action. Kuldeep provided a perfect example when he bamboozled both Jonny Bairstow and Joe Root with successive wrong'uns in the opening T20 at Old Trafford.

The fact that Bairstow - a wicketkeeper by trade - was deceived by the wrong'un is symptomatic of a malaise that is sweeping international batting - a general inability to read wristspinners. This failing is not only the root cause of wicket loss from mishits but also contributes to a desirable bowling economy rate for the bowlers, as batsmen are hesitant to attack a delivery they are unsure about. This inability to read wristspinners is mystifying.

If a batsman watches the ball out of the hand, the early warning signals are available. A legbreak is delivered with the back of the hand turned towards the bowler's face, while with the wrong'un, it's facing the batsman. As a further indicator, the wrong'un, because it's bowled out of the back of the hand, has a slightly loftier trajectory. Final confirmation is provided by the seam position, which is tilted towards first slip for the legspinner, and leg slip for the wrong'un. Any batsman waiting to pick the delivery off the pitch is depriving himself of scoring opportunities and putting his wicket in danger.

When Shane Warne was at his devastating peak, fans marvelled at his repertoire and said it was the main reason for his success. "Picking him is the easy part," I explained, "it's playing him that's difficult."

Richie Benaud, another master of the art, summed up spin bowling best: "It's the subtle variations," he proffered, "that bring the most success."

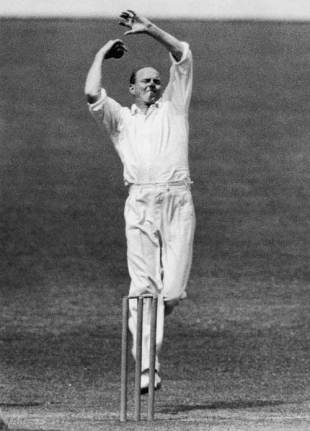

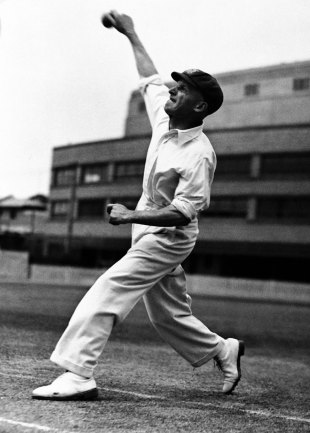

O'Reilly was not only an aggressive leggie but also a wily one, and he bent his back leg when he wanted to vary his pace. This action altered his release point without slowing his arm speed, and consequently it was difficult for the batsman to detect the subtle variation.

This type of information is crucial to successful batsmanship, but following Kuldeep's demolition job, Jos Buttler said it might take one or two games for English batsmen to get used to the left-armer. This is an indictment of the current system for developing young batsmen, where you send them into international battle minus a few important tools.

It's not only the range of strokes that has dramatically evolved in short-format batting but also the mental approach. Contrast the somnambulistic approach of Essex's Brian Ward in a 1969 40-over game with England's record-breaking assault on the Australian bowling at Trent Bridge recently.

Ward decided that Somerset offspinner Brian Langford was the danger man in the opposition attack, and eight consecutive maidens resulted, handing the bowler the never-to-be-repeated figures of 8-8-0-0. On the other hand England's batsmen this year displayed no such inhibitions in rattling up 481 off 50 overs, and Australia's bowlers, headed by Andrew Tye, with 9-0-100-0, were pummelled.

Nevertheless one thing has remained constant in the short formats: a wariness around spin bowling, although currently it's more likely to be the wrist variety than fingerspin.

The list of successful wristspinners in short-format cricket is growing rapidly and there have been some outstanding recent performances. Afghanistan's Rashid Khan was the joint leading wicket-taker in the BBL; England's Adil Rashid (along with spin-bowling companion Moeen Ali), took the most wicketsin the recent whitewash of Australia; and in successive T20Is against England, India's duo of Yuzvendra Chahal and Kuldeep Yadav have claimed the rare distinction of a five-wicket haul. It's a trail of destruction that have would gladdened the heart of Bill "Tiger" O'Reilly, a great wristspinner himself and the most insistent promoter of the art there has ever been.

Wristspinners are extremely successful in the shorter formats and are being eagerly sought after for the many T20 leagues. Their enormous success is mostly down to the deception they provide, since they are able to turn it from both leg and off with only a minimal change of action. Kuldeep provided a perfect example when he bamboozled both Jonny Bairstow and Joe Root with successive wrong'uns in the opening T20 at Old Trafford.

The fact that Bairstow - a wicketkeeper by trade - was deceived by the wrong'un is symptomatic of a malaise that is sweeping international batting - a general inability to read wristspinners. This failing is not only the root cause of wicket loss from mishits but also contributes to a desirable bowling economy rate for the bowlers, as batsmen are hesitant to attack a delivery they are unsure about. This inability to read wristspinners is mystifying.

If a batsman watches the ball out of the hand, the early warning signals are available. A legbreak is delivered with the back of the hand turned towards the bowler's face, while with the wrong'un, it's facing the batsman. As a further indicator, the wrong'un, because it's bowled out of the back of the hand, has a slightly loftier trajectory. Final confirmation is provided by the seam position, which is tilted towards first slip for the legspinner, and leg slip for the wrong'un. Any batsman waiting to pick the delivery off the pitch is depriving himself of scoring opportunities and putting his wicket in danger.

When Shane Warne was at his devastating peak, fans marvelled at his repertoire and said it was the main reason for his success. "Picking him is the easy part," I explained, "it's playing him that's difficult."

Richie Benaud, another master of the art, summed up spin bowling best: "It's the subtle variations," he proffered, "that bring the most success."

O'Reilly was not only an aggressive leggie but also a wily one, and he bent his back leg when he wanted to vary his pace. This action altered his release point without slowing his arm speed, and consequently it was difficult for the batsman to detect the subtle variation.

This type of information is crucial to successful batsmanship, but following Kuldeep's demolition job, Jos Buttler said it might take one or two games for English batsmen to get used to the left-armer. This is an indictment of the current system for developing young batsmen, where you send them into international battle minus a few important tools.

Tuesday, 27 October 2015

On leg spin - Straight from the wrist

Source: Cricinfo

Imran Tahir on Abdul Qadir: "He could easily mesmerise someone like the 17-year-old me. He was the guy I wanted to be"© AFP

INTERVIEWS BY NAGRAJ GOLLAPUDI AND GAURAV KALRA | OCTOBER 2015

It takes heart, it takes skill, it takes brains, and it makes for the most tantalising sight in cricket. Three legspinners with three decades of experience around the world tell us how it's done.

What skills are necessary to become a good legspinner?

Mushtaq Ahmed: You've got to spin the ball. That is the most important thing. Then you need to have the variations: legbreak, wrong'un, flipper, topspinner. Then your action needs to be very repeatable. You should know how to use the crease, know when to go round the wicket. Those are the basics.

You have to spin the ball with drift. I learned that in the last five years of my career. It was difficult for me because of my action, where my arm was very high. Drift is something that forces the batsman usually to get caught at the wicket, in slips and gully. I can never tire of watching a legspinner who can drift the ball in and spin the ball away from a right-hander.

Stuart MacGill: The number one attribute for a spin bowler is resilience. You have to take a pile of beatings before you can become an international bowler. You can't judge a legspinner based on the number of bad balls he bowls in an over. You have to judge him at the end of the day, based on the number of wickets he has taken. If a young spinner bowls ten or 20 bad balls, it is the ball he bowls that belongs in the Shane Warnevideo category that should keep him going the next day. If you are more interested in the batsman hitting sixes, then you should be a batsman. If you're the bloke interested in getting the batsman out when he's on top, then you stand a chance.

Imran Tahir: With time and experience you start learning the skills. For me what is important is, as a legspinner you need determination, especially in modern-day cricket. You need to feel that you can change a game. Legspinners are exciting characters. Look at guys like Warne, Qadir - they change results, they make things happen.

Mushtaq: I was very lucky that I could imitate people easily. At school I used to act like Imran Khan by copying his bowling action. If Javed Miandad scored runs, I would walk like him, field like him. When I saw Abdul Qadir for the first time on TV, I liked his bouncing, dancing action. I copied him instantly. I did not have his height, but I felt that I could bowl legspin. For the first two years of my career I bowled exactly like Qadir bhai.

I met Qadir bhai for the first time in 1987. I played in a tour match against Mike Gatting's England. I was a schoolboy, but I took six wickets in the first innings. I was picked in the Test squad and met him in Karachi. I was shy so I did not approach him, but I watched him very closely. What I observed from his body language was that he was very confident. I have since believed, and I always tell this to young bowlers, the most important thing you need to have as a legspinner is confidence. Your body language should always be that of a fast bowler, but you need to think like a spinner. When somebody hits you for a six, you need to still look into the batsman's eye, but you need to be cool and keep in mind that you still have to spin the ball.

Tahir: Abdul Qadir was my main role model. I just wanted to be like him because for me he was only guy who no one could read. He was that good. His passion, his love for legspin, was unique. He would create new things all the time: flippers, sliders, three to four kinds of googlies, legspinners, topspinners. He could easily mesmerise someone like the 17-year-old me. He was the guy I wanted to be.

MacGill: "The pressure applied by Shane is far more significant than the pressure applied by me, and consequently it was easier for me to take wickets" © Getty Images

MacGill: My father and grandfather were first-class cricketers. Being born into a cricketing family, I was always gunning to play cricket. Most kids in the '70s and '80s wanted to be fast bowlers and emulate Dennis Lillee but my father was a legspinner. He was a very different bowler to me as he relied on accuracy and change of pace along with variation off the pitch.

Clarrie Grimmett and Bill O'Reilly were really big names in Australian cricket folklore. I have read Grimmett's books and it's amazing how their generation learnt through feel in the absence of technology. I really like them because they played together but were different bowlers and different personalities. O'Reilly sometimes bowled with the new ball. They succeeded to the point that rules were changed to protect the batsmen.

I met Warnie when we were at the cricket academy in 1990, shortly before he played for Australia. I never compared myself with Shane Warne. I wasn't even playing state cricket back then. In his success was my opportunity as we started to rely more and more on a spin bowler as an attacking component.

A calculated dismissal: Mushtaq Ahmed goes round the wicket and traps Michael Atherton at The Oval in 1996 © Getty Images

Mushtaq: It would be the 1992 World Cup final, when I got three wickets. I had 16 wickets in nine matches, just behind Wasim [Akram] who had 18 wickets in ten matches. After that I realised I can play international cricket.

After the World Cup, Pakistan toured England where we won the series. And even if Wasim and Waqar dominated, I still had 15 wickets. That gave me the confidence that if I get more opportunities I could dominate too. That belief was confirmed on the 1995 tour of Australia, where I got 18 wickets including nine wickets in Sydney. I remember Australian captain Mark Taylor saying Mushy was the most difficult legspinner he had faced. That was because he could not read my googly.

I had also become more accurate and versatile playing county cricket. I enjoyed the responsibility. In county cricket you play in different weather conditions - cold, hot, rainy - you play on slow, turning, green pitches, so once you experience all these varied conditions you become a very matured bowler.

Tahir: That spell against Pakistan in Dubai when I got 5 for 32 was the most important. That is the only five-for I have got in my Test career. It had come against some of the best batsmen of spin on one of the flattest decks. I had played against most of the Pakistan batsmen, including Misbah-ul-Haq, as a youngster and that made it more special.

Is spinning the ball mandatory?

MacGill: Nowadays there's a temptation to turn everybody into Shane Warne. Being a wristspinner doesn't mean you need to have the same approach as Shane Warne. I loved watching Anil Kumble bowl. I thought he was great. People who said that he didn't turn the ball didn't know the huge amount of work he got into the ball. He generated a lot of revolutions and the ball did drop a lot through the air. His height was an advantage but he moulded his bowling around what he had physically. He was a superstar. People focus on what happens to the ball off the pitch but a great batsman is beaten before the ball pitches.

MacGill: "You can't judge a legspinner based on the number of bad balls he bowls in an over" © Getty Images

Mushtaq: My legbreaks, I did not spin them much. But there was enough spin to create doubts in the batsman's mind. When you are at your peak, when you are bowling your legbreaks, wrong'uns, and flippers and even the best batsmen are not reading you, for doing that you have got to be a good spinner of the ball.

I will cite the example of Kumble. His stats are brilliant. He was unplayable where the pitches were helpful. If the pitch was dry, turning, breaking, he was a very difficult bowler to play because he was tall, he would get bounce and had good pace behind the ball. But in Australia, South Africa and England, places where the pitches are not turning enough, it became difficult. Where pitches are unhelpful if you are not a big spinner of the ball, people can play you off the pitch or like a medium-pacer.

Tahir: No, it is not. I had spoken about the same thing with Shane Warne when I met him. I wanted to turn the ball like him, I told him. He said I should not bother about spinning more than the size of the bat otherwise I would not gain the edge. Perhaps he said that after having observed my bowling action. He did teach me a few grips, how he used to hold the ball, but he asked me to stick to my own action and focus on my strengths. In modern-day cricket there is no legspinner who turns the ball big.

What's the process for developing the various deliveries that legspinners bowl?

MacGill: The process is that everybody has their stock ball, which I like to call their best ball. The ball you can fall back on and which you can bowl with your eyes shut. You then understand the angle of the wrist and the angle of the release. That is the only thing that matters. Pace through the air can be generated through your body. You can go a little bit wider or go round the wicket, but the angle of your wrist and point of release determines the type of delivery. There are gentle differences in the degree. If my palm faces the batsman, it's a legbreak. There are no magical deliveries. It's all about the angle of release.

I tried to get one at a time. The first and most difficult one was the googly, so I tried to spend a lot of time developing that. Unfortunately for me, I tried to develop it to the detriment of my legspinner. It took me six months to get my legspinner back. It took me longer to learn the backspinner as I found it difficult to incorporate it into my action. In the end it was one of my better variations.

Mushtaq Ahmed: "I learned drift in the last five years of my career. It was difficult for me because of my action, where my arm was very high" © PA Photos

How important is the stock ball?

Tahir: My belief is whatever be my stock ball, the key is to keep the batsman guessing every ball. I want him to think all the time. I should not be predictable to the batsman. If you spin the ball big like Shane Warne, then you are bound to trouble the batsman. But if you cannot, then you need to play mind games.

Mushtaq: People used to think my googly was my stock ball. As a legspinner, the stock ball for me is the legbreak. I would bowl it with a scrambled seam. Because I had a quick arm action, batsmen could not pick it from the seam or my hand. With experience I brought in the variations to the legbreak. You have to watch the batsman, read him. If somebody plays with hard hands then you have to bowl slow. You have to deceive him with the pace of the ball. If somebody is playing with soft hands you've got to push the ball quicker.

At times you have to bowl legbreaks wide of the crease, sometimes you pitch it from closer to the stumps. In between you bowl a wrong'un and topspinner from the same area, which makes it more difficult for the batsman. If he is good at reading the hand or reading your wrong'un then you should go round the wicket to put a doubt in his mind and then swap to over the wicket.

Possibly a good example of that strategy could be you getting Michael Atherton out twice, both times on the final day, of the Lord's and The Oval Tests in 1996. You went round the wicket both times. What was the plan?

Mushtaq:I remembered Atherton used to be a legspinner, so he would play with very soft hands. He would easily push me to cover. He would put his front leg outside off stump and that way he would kill or put away my googly. Then I realised that I have to bowl from round the wicket because he is going across. By going round the wicket he would be forced to open up, which he was not used to. He had to play me from the leg stump and consequently he was caught at bat-pad and once at slip.

Can there be a temptation to overuse the googly? During the initial phase of your county career Martin Crowe, the opposition captain, asked his batsmen to play you as an offspinner.

Mushtaq: It really hurt when I was told about Crowe's plan. But what he said proved beneficial for me because I decided that I would improve my legspinner so much that even if they played me like an offspinner I could get them in my sleep. But I must admit that when I realised that a batsman could not read me I used to overcompensate with my googlies. After Crowe made that statement I started to spin my legbreaks more, spin my flippers more, spin my topspinners more. A lot of people would at times misread my topspinner, where the ball would stop and get extra bounce, as a googly.

Tahir: "Legspinners are exciting characters. They change results, they make things happen" © Getty Images

Who were the batsmen you enjoyed bowling most against?

MacGill: The batsman who destroyed spin bowling consistently was Brian Lara. I certainly enjoyed getting him out, though it didn't happen all that often. I liked bowling to him because that was the ultimate challenge. Lara smashed the daylights out of me at Adelaide in the early 2000s and I really lost the plot. I didn't bowl well for the rest of the innings to any batsman and I got dropped from the Australian team. I worked on a few things and then picked him up in Sydney in the first innings and had a dropped catch in the second innings. I could have had him in both innings, which was a good turnaround. I did enjoy that.

I enjoyed bowling to VVS Laxman because he was different and watching him bat was enjoyable. He is a nice guy. Bowling to him, I knew that if I bowled poorly, I'll get destroyed and if I bowled well, it didn't mean I'll necessarily get him out. I loved bowling to him at Melbourne [in 2003-04], where I bowled well. My reaction shows how highly Laxman's wicket was valued by me. I also enjoyed bowling to Rahul Dravid, as in 2003 his batting suddenly changed. I had bowled to him in the past where I could think of certain ways of getting him out. But in 2003 I could not think of ways to get him out.

Can you talk a little about how Lara played you differently from other batsmen?

MacGill: He hit me to areas that I hadn't been hit to before. When you're bowling spin, you should aim to hit the top of off stump. So I tried to pitch the ball outside his off stump, because if the ball is turning, the over-the-wicket angle provides you an advantage. The ball was turning a lot in that [Adelaide] match, but Lara was not perturbed about that. He was able to hit me off the front foot anywhere in the arc between mid-off and backward point. It was a sign of his mastery with the bat.

Mushtaq: Brian Lara was the batsman who came close to destroying my confidence. His feet and hands were quick. He could hit even your good balls for four. He has said that he never picked my hand, nor my googly. But his hand-eye coordination was amazing. Lara could hit the ball pitched in the rough in two different places. If the ball was pitched in the rough and spun in, Lara would cut the ball. And if I moved the fielder to defend the cut, Lara would hit the same ball to extra cover. He used to have that much time. If you can cut, sweep, punch on the back foot and use your feet, then you will be successful against a legspinner. Lara was one of them. The other guy was Darren Lehmann. He used to give me a proper hard time both in county cricket and in the few Test matches I played against him.

What do you do when you can't land a ball?

MacGill: It's only happened once to me and it's incredibly embarrassing because you know that you're better than that and you've got to do better not only for yourself but also for the guy at the other end. If I'm bowling absolute rubbish, I'm letting him down, it makes it much more difficult for them to do their job. The best you can do is fall back on your best delivery and hopefully it works.

Anil Kumble didn't turn the ball much but he put in a huge amount of work on the ball to deceive batsmen © Global Cricket Ventures-BCCI

Mushtaq: I have suffered such a fate lots of times, especially when I was under pressure. In such a situation the key is to try and come back to your basics. Do not try to spin the ball too much. At times it could be very cold weather, or when the conditions are wet you cannot grip and control the ball properly. I would shut out the batsman in such a situation. I would not bother about whether he was using his feet, whether he was going to hurt me. I would tell myself: "This is my action. This is where I am going to land."

Tahir: It mostly happens when the conditions are cold. You cannot grip the ball properly and it takes a few overs to warm up and settle down. The other reason can be duress. In my secondTest, against Australia, I could not land the ball consistently because of the pressure. I was bowling full tosses, short balls, but it was the early part of my international career. I bounced back strongly by taking three wickets in that innings.

What role do you see for a legspinner in T20 cricket?

MacGill: Spin bowlers have taken wickets in T20 cricket right since its inception. It's a game that is dominated by the bat but won by the ball. Spinners have dominated T20 cricket because the batsman is obliged to play shots. If you spin the ball, then you open up one side of the field. The batsman has to hit against the spin to hit to the other side. The turn as opposed to the spin is what gives you the advantage in T20 cricket, as you cut down on the scoring options. I don't think it matters whether you're a fingerspinner or a legspinner.

Mushtaq: Not just T20, even in ODIs the more successful spinner is the legspinner, especially with the two new balls. When the legspinner has a new ball he can bounce it, skid it, spin it. Delhi Daredevils played Amit Mishra and Imran Tahir in the IPL this season and both took wickets. In the early part of my career, Imran Khan saab played Qadir bhai and myself a lot in ODIs and a few Test matches. The reason a legspinner is more successful in T20 cricket is because of his variations and the bounce he can derive off the wicket. If a batsman tries to hit a legspinner over mid-on or midwicket you stand a good chance to get a top edge as he's playing against the spin.

Also remember this, if a legspinner can land the ball in a good spot the batsman cannot take an easy single. Against a left-arm spinner or an offspinner you can sweep or step out or push for a safe single to mid-off or mid-on. But against a legspinner the batsman is edgy to sweep for the fear of the ball skidding in or bouncing, or getting stumped if he charges down. If you get two or three dot balls in T20, the batsman starts looking for a boundary, and in that situation a legspinner stands a good chance of taking a wicket.

MacGill: I loved bowling people, right-handers and left-handers. Obviously right-handers was a little more difficult unless I was bowling the googly. I really enjoyed bowling left-handers, and bowling to left-handers.

Tahir: The googly and the slider are my favourite type of deliveries and I love it when batsmen try to cut or sweep me and while attempting those strokes get lbw or clean bowled. I remember Misbah in the Dubai Test, who I feel had read my googly but was still beaten. It gave me immense joy because Misbah was my state captain in Pakistan when I was a young leggie and despite knowing my bowling and despite having picked the wrong'un, he still went for the shot and was deceived.

Mushtaq: Nothing gave me more joy than watching a batsman who would be lured into attempting a drive against a googly which he could not read and the ball pierced through the gap between his bat and pad and hit the stumps. That was my best moment. My favourite dismissal remains the googly that beat Graeme Hick [lbw] in the 1992 World Cup final. I still enjoy watching that ball. Steve Waugh, if I'm not wrong, was bowled in the Sydney Test [1995-96] trying to drive. David Boon was clean bowled in the Rawalpindi Test [1994-95], again attempting a drive.

Imran Tahir on Abdul Qadir: "He could easily mesmerise someone like the 17-year-old me. He was the guy I wanted to be"© AFP

INTERVIEWS BY NAGRAJ GOLLAPUDI AND GAURAV KALRA | OCTOBER 2015

It takes heart, it takes skill, it takes brains, and it makes for the most tantalising sight in cricket. Three legspinners with three decades of experience around the world tell us how it's done.

What skills are necessary to become a good legspinner?

Mushtaq Ahmed: You've got to spin the ball. That is the most important thing. Then you need to have the variations: legbreak, wrong'un, flipper, topspinner. Then your action needs to be very repeatable. You should know how to use the crease, know when to go round the wicket. Those are the basics.

You have to spin the ball with drift. I learned that in the last five years of my career. It was difficult for me because of my action, where my arm was very high. Drift is something that forces the batsman usually to get caught at the wicket, in slips and gully. I can never tire of watching a legspinner who can drift the ball in and spin the ball away from a right-hander.

Stuart MacGill: The number one attribute for a spin bowler is resilience. You have to take a pile of beatings before you can become an international bowler. You can't judge a legspinner based on the number of bad balls he bowls in an over. You have to judge him at the end of the day, based on the number of wickets he has taken. If a young spinner bowls ten or 20 bad balls, it is the ball he bowls that belongs in the Shane Warnevideo category that should keep him going the next day. If you are more interested in the batsman hitting sixes, then you should be a batsman. If you're the bloke interested in getting the batsman out when he's on top, then you stand a chance.

Imran Tahir: With time and experience you start learning the skills. For me what is important is, as a legspinner you need determination, especially in modern-day cricket. You need to feel that you can change a game. Legspinners are exciting characters. Look at guys like Warne, Qadir - they change results, they make things happen.

"You have to watch the batsman, read him. If somebody plays with hard hands you have to bowl slow. You have to deceive him with pace"MUSHTAQ AHMED

Did any bowlers from history have an impact on you?

Did any bowlers from history have an impact on you?

Mushtaq: I was very lucky that I could imitate people easily. At school I used to act like Imran Khan by copying his bowling action. If Javed Miandad scored runs, I would walk like him, field like him. When I saw Abdul Qadir for the first time on TV, I liked his bouncing, dancing action. I copied him instantly. I did not have his height, but I felt that I could bowl legspin. For the first two years of my career I bowled exactly like Qadir bhai.

I met Qadir bhai for the first time in 1987. I played in a tour match against Mike Gatting's England. I was a schoolboy, but I took six wickets in the first innings. I was picked in the Test squad and met him in Karachi. I was shy so I did not approach him, but I watched him very closely. What I observed from his body language was that he was very confident. I have since believed, and I always tell this to young bowlers, the most important thing you need to have as a legspinner is confidence. Your body language should always be that of a fast bowler, but you need to think like a spinner. When somebody hits you for a six, you need to still look into the batsman's eye, but you need to be cool and keep in mind that you still have to spin the ball.

Tahir: Abdul Qadir was my main role model. I just wanted to be like him because for me he was only guy who no one could read. He was that good. His passion, his love for legspin, was unique. He would create new things all the time: flippers, sliders, three to four kinds of googlies, legspinners, topspinners. He could easily mesmerise someone like the 17-year-old me. He was the guy I wanted to be.

MacGill: "The pressure applied by Shane is far more significant than the pressure applied by me, and consequently it was easier for me to take wickets" © Getty Images

MacGill: My father and grandfather were first-class cricketers. Being born into a cricketing family, I was always gunning to play cricket. Most kids in the '70s and '80s wanted to be fast bowlers and emulate Dennis Lillee but my father was a legspinner. He was a very different bowler to me as he relied on accuracy and change of pace along with variation off the pitch.

Clarrie Grimmett and Bill O'Reilly were really big names in Australian cricket folklore. I have read Grimmett's books and it's amazing how their generation learnt through feel in the absence of technology. I really like them because they played together but were different bowlers and different personalities. O'Reilly sometimes bowled with the new ball. They succeeded to the point that rules were changed to protect the batsmen.

I met Warnie when we were at the cricket academy in 1990, shortly before he played for Australia. I never compared myself with Shane Warne. I wasn't even playing state cricket back then. In his success was my opportunity as we started to rely more and more on a spin bowler as an attacking component.

"You should never have fear in T20. Even if you are hit for 20 runs in an over, in the next over by taking two wickets you can finish the game"IMRAN TAHIR

How do you explain having a superior record to Warne in the games you played together?

MacGill: When I was bowling I was lucky I had Shane Warne up the other end. When he was bowling, he had me up the other end. The pressure applied by Shane is far more significant than the pressure applied by me and consequently it was easier for me to take wickets because they had to score off me as they were not scoring off him.

Warne came into the side when spin bowling was not used as front-line attack. We had some seriously attacking spinners like Ashley Mallett but then there was a gap. Bruce Yardley was another one, Greg Matthews became an attacking spinner in the second half of his career, but none of them got an extended run and became a core member of the team. Warne showed nations around the world the importance of having a diverse attack.

Was there a spell from your early days which gave you the confidence that you belong?

MacGill: I always cared about taking wickets and not the runs I gave away. In one of my first games of fourth-grade cricket I got hit for nine sixes by a first-grade batsman. But I got six wickets in the game the next week.

How do you explain having a superior record to Warne in the games you played together?

MacGill: When I was bowling I was lucky I had Shane Warne up the other end. When he was bowling, he had me up the other end. The pressure applied by Shane is far more significant than the pressure applied by me and consequently it was easier for me to take wickets because they had to score off me as they were not scoring off him.

Warne came into the side when spin bowling was not used as front-line attack. We had some seriously attacking spinners like Ashley Mallett but then there was a gap. Bruce Yardley was another one, Greg Matthews became an attacking spinner in the second half of his career, but none of them got an extended run and became a core member of the team. Warne showed nations around the world the importance of having a diverse attack.

Was there a spell from your early days which gave you the confidence that you belong?

MacGill: I always cared about taking wickets and not the runs I gave away. In one of my first games of fourth-grade cricket I got hit for nine sixes by a first-grade batsman. But I got six wickets in the game the next week.

A calculated dismissal: Mushtaq Ahmed goes round the wicket and traps Michael Atherton at The Oval in 1996 © Getty Images

Mushtaq: It would be the 1992 World Cup final, when I got three wickets. I had 16 wickets in nine matches, just behind Wasim [Akram] who had 18 wickets in ten matches. After that I realised I can play international cricket.

After the World Cup, Pakistan toured England where we won the series. And even if Wasim and Waqar dominated, I still had 15 wickets. That gave me the confidence that if I get more opportunities I could dominate too. That belief was confirmed on the 1995 tour of Australia, where I got 18 wickets including nine wickets in Sydney. I remember Australian captain Mark Taylor saying Mushy was the most difficult legspinner he had faced. That was because he could not read my googly.

I had also become more accurate and versatile playing county cricket. I enjoyed the responsibility. In county cricket you play in different weather conditions - cold, hot, rainy - you play on slow, turning, green pitches, so once you experience all these varied conditions you become a very matured bowler.

"Your body language should always be that of a fast bowler, but you need to think like a spinner"MUSHTAQ AHMED

Tahir: That spell against Pakistan in Dubai when I got 5 for 32 was the most important. That is the only five-for I have got in my Test career. It had come against some of the best batsmen of spin on one of the flattest decks. I had played against most of the Pakistan batsmen, including Misbah-ul-Haq, as a youngster and that made it more special.

Is spinning the ball mandatory?

MacGill: Nowadays there's a temptation to turn everybody into Shane Warne. Being a wristspinner doesn't mean you need to have the same approach as Shane Warne. I loved watching Anil Kumble bowl. I thought he was great. People who said that he didn't turn the ball didn't know the huge amount of work he got into the ball. He generated a lot of revolutions and the ball did drop a lot through the air. His height was an advantage but he moulded his bowling around what he had physically. He was a superstar. People focus on what happens to the ball off the pitch but a great batsman is beaten before the ball pitches.

MacGill: "You can't judge a legspinner based on the number of bad balls he bowls in an over" © Getty Images

Mushtaq: My legbreaks, I did not spin them much. But there was enough spin to create doubts in the batsman's mind. When you are at your peak, when you are bowling your legbreaks, wrong'uns, and flippers and even the best batsmen are not reading you, for doing that you have got to be a good spinner of the ball.

I will cite the example of Kumble. His stats are brilliant. He was unplayable where the pitches were helpful. If the pitch was dry, turning, breaking, he was a very difficult bowler to play because he was tall, he would get bounce and had good pace behind the ball. But in Australia, South Africa and England, places where the pitches are not turning enough, it became difficult. Where pitches are unhelpful if you are not a big spinner of the ball, people can play you off the pitch or like a medium-pacer.

Tahir: No, it is not. I had spoken about the same thing with Shane Warne when I met him. I wanted to turn the ball like him, I told him. He said I should not bother about spinning more than the size of the bat otherwise I would not gain the edge. Perhaps he said that after having observed my bowling action. He did teach me a few grips, how he used to hold the ball, but he asked me to stick to my own action and focus on my strengths. In modern-day cricket there is no legspinner who turns the ball big.

"The googly and the slider are my favourite type of deliveries and I love it when batsmen try to cut or sweep me"IMRAN TAHIR

What's the process for developing the various deliveries that legspinners bowl?

MacGill: The process is that everybody has their stock ball, which I like to call their best ball. The ball you can fall back on and which you can bowl with your eyes shut. You then understand the angle of the wrist and the angle of the release. That is the only thing that matters. Pace through the air can be generated through your body. You can go a little bit wider or go round the wicket, but the angle of your wrist and point of release determines the type of delivery. There are gentle differences in the degree. If my palm faces the batsman, it's a legbreak. There are no magical deliveries. It's all about the angle of release.

I tried to get one at a time. The first and most difficult one was the googly, so I tried to spend a lot of time developing that. Unfortunately for me, I tried to develop it to the detriment of my legspinner. It took me six months to get my legspinner back. It took me longer to learn the backspinner as I found it difficult to incorporate it into my action. In the end it was one of my better variations.

Mushtaq Ahmed: "I learned drift in the last five years of my career. It was difficult for me because of my action, where my arm was very high" © PA Photos

How important is the stock ball?

Tahir: My belief is whatever be my stock ball, the key is to keep the batsman guessing every ball. I want him to think all the time. I should not be predictable to the batsman. If you spin the ball big like Shane Warne, then you are bound to trouble the batsman. But if you cannot, then you need to play mind games.

Mushtaq: People used to think my googly was my stock ball. As a legspinner, the stock ball for me is the legbreak. I would bowl it with a scrambled seam. Because I had a quick arm action, batsmen could not pick it from the seam or my hand. With experience I brought in the variations to the legbreak. You have to watch the batsman, read him. If somebody plays with hard hands then you have to bowl slow. You have to deceive him with the pace of the ball. If somebody is playing with soft hands you've got to push the ball quicker.

At times you have to bowl legbreaks wide of the crease, sometimes you pitch it from closer to the stumps. In between you bowl a wrong'un and topspinner from the same area, which makes it more difficult for the batsman. If he is good at reading the hand or reading your wrong'un then you should go round the wicket to put a doubt in his mind and then swap to over the wicket.

"The angle of your wrist and point of release determines the type of delivery"STUART MACGILL

Possibly a good example of that strategy could be you getting Michael Atherton out twice, both times on the final day, of the Lord's and The Oval Tests in 1996. You went round the wicket both times. What was the plan?

Mushtaq:I remembered Atherton used to be a legspinner, so he would play with very soft hands. He would easily push me to cover. He would put his front leg outside off stump and that way he would kill or put away my googly. Then I realised that I have to bowl from round the wicket because he is going across. By going round the wicket he would be forced to open up, which he was not used to. He had to play me from the leg stump and consequently he was caught at bat-pad and once at slip.

Can there be a temptation to overuse the googly? During the initial phase of your county career Martin Crowe, the opposition captain, asked his batsmen to play you as an offspinner.

Mushtaq: It really hurt when I was told about Crowe's plan. But what he said proved beneficial for me because I decided that I would improve my legspinner so much that even if they played me like an offspinner I could get them in my sleep. But I must admit that when I realised that a batsman could not read me I used to overcompensate with my googlies. After Crowe made that statement I started to spin my legbreaks more, spin my flippers more, spin my topspinners more. A lot of people would at times misread my topspinner, where the ball would stop and get extra bounce, as a googly.

Tahir: "Legspinners are exciting characters. They change results, they make things happen" © Getty Images

Who were the batsmen you enjoyed bowling most against?

MacGill: The batsman who destroyed spin bowling consistently was Brian Lara. I certainly enjoyed getting him out, though it didn't happen all that often. I liked bowling to him because that was the ultimate challenge. Lara smashed the daylights out of me at Adelaide in the early 2000s and I really lost the plot. I didn't bowl well for the rest of the innings to any batsman and I got dropped from the Australian team. I worked on a few things and then picked him up in Sydney in the first innings and had a dropped catch in the second innings. I could have had him in both innings, which was a good turnaround. I did enjoy that.

I enjoyed bowling to VVS Laxman because he was different and watching him bat was enjoyable. He is a nice guy. Bowling to him, I knew that if I bowled poorly, I'll get destroyed and if I bowled well, it didn't mean I'll necessarily get him out. I loved bowling to him at Melbourne [in 2003-04], where I bowled well. My reaction shows how highly Laxman's wicket was valued by me. I also enjoyed bowling to Rahul Dravid, as in 2003 his batting suddenly changed. I had bowled to him in the past where I could think of certain ways of getting him out. But in 2003 I could not think of ways to get him out.

"People focus on what happens to the ball off the pitch but a great batsman is beaten before the ball pitches"STUART MACGILL

Can you talk a little about how Lara played you differently from other batsmen?

MacGill: He hit me to areas that I hadn't been hit to before. When you're bowling spin, you should aim to hit the top of off stump. So I tried to pitch the ball outside his off stump, because if the ball is turning, the over-the-wicket angle provides you an advantage. The ball was turning a lot in that [Adelaide] match, but Lara was not perturbed about that. He was able to hit me off the front foot anywhere in the arc between mid-off and backward point. It was a sign of his mastery with the bat.

Mushtaq: Brian Lara was the batsman who came close to destroying my confidence. His feet and hands were quick. He could hit even your good balls for four. He has said that he never picked my hand, nor my googly. But his hand-eye coordination was amazing. Lara could hit the ball pitched in the rough in two different places. If the ball was pitched in the rough and spun in, Lara would cut the ball. And if I moved the fielder to defend the cut, Lara would hit the same ball to extra cover. He used to have that much time. If you can cut, sweep, punch on the back foot and use your feet, then you will be successful against a legspinner. Lara was one of them. The other guy was Darren Lehmann. He used to give me a proper hard time both in county cricket and in the few Test matches I played against him.

What do you do when you can't land a ball?

MacGill: It's only happened once to me and it's incredibly embarrassing because you know that you're better than that and you've got to do better not only for yourself but also for the guy at the other end. If I'm bowling absolute rubbish, I'm letting him down, it makes it much more difficult for them to do their job. The best you can do is fall back on your best delivery and hopefully it works.

Anil Kumble didn't turn the ball much but he put in a huge amount of work on the ball to deceive batsmen © Global Cricket Ventures-BCCI

Mushtaq: I have suffered such a fate lots of times, especially when I was under pressure. In such a situation the key is to try and come back to your basics. Do not try to spin the ball too much. At times it could be very cold weather, or when the conditions are wet you cannot grip and control the ball properly. I would shut out the batsman in such a situation. I would not bother about whether he was using his feet, whether he was going to hurt me. I would tell myself: "This is my action. This is where I am going to land."

Tahir: It mostly happens when the conditions are cold. You cannot grip the ball properly and it takes a few overs to warm up and settle down. The other reason can be duress. In my secondTest, against Australia, I could not land the ball consistently because of the pressure. I was bowling full tosses, short balls, but it was the early part of my international career. I bounced back strongly by taking three wickets in that innings.

What role do you see for a legspinner in T20 cricket?

MacGill: Spin bowlers have taken wickets in T20 cricket right since its inception. It's a game that is dominated by the bat but won by the ball. Spinners have dominated T20 cricket because the batsman is obliged to play shots. If you spin the ball, then you open up one side of the field. The batsman has to hit against the spin to hit to the other side. The turn as opposed to the spin is what gives you the advantage in T20 cricket, as you cut down on the scoring options. I don't think it matters whether you're a fingerspinner or a legspinner.

Mushtaq: Not just T20, even in ODIs the more successful spinner is the legspinner, especially with the two new balls. When the legspinner has a new ball he can bounce it, skid it, spin it. Delhi Daredevils played Amit Mishra and Imran Tahir in the IPL this season and both took wickets. In the early part of my career, Imran Khan saab played Qadir bhai and myself a lot in ODIs and a few Test matches. The reason a legspinner is more successful in T20 cricket is because of his variations and the bounce he can derive off the wicket. If a batsman tries to hit a legspinner over mid-on or midwicket you stand a good chance to get a top edge as he's playing against the spin.

Also remember this, if a legspinner can land the ball in a good spot the batsman cannot take an easy single. Against a left-arm spinner or an offspinner you can sweep or step out or push for a safe single to mid-off or mid-on. But against a legspinner the batsman is edgy to sweep for the fear of the ball skidding in or bouncing, or getting stumped if he charges down. If you get two or three dot balls in T20, the batsman starts looking for a boundary, and in that situation a legspinner stands a good chance of taking a wicket.

"Brian Lara was the batsman who came close to destroying my confidence. His feet and hands were quick. He could hit even your good balls for four"MUSHTAQ AHMED

Tahir: You should never have fear in T20. You need to go in with a big heart. You need to back your skills. You need clear plans. Even if you are hit for 20 runs in an over, and this is my advice to a youngster, in the next over by taking two middle-order wickets you can easily finish the game.

What was your favourite mode of dismissal?

Tahir: You should never have fear in T20. You need to go in with a big heart. You need to back your skills. You need clear plans. Even if you are hit for 20 runs in an over, and this is my advice to a youngster, in the next over by taking two middle-order wickets you can easily finish the game.

What was your favourite mode of dismissal?

MacGill: I loved bowling people, right-handers and left-handers. Obviously right-handers was a little more difficult unless I was bowling the googly. I really enjoyed bowling left-handers, and bowling to left-handers.

Tahir: The googly and the slider are my favourite type of deliveries and I love it when batsmen try to cut or sweep me and while attempting those strokes get lbw or clean bowled. I remember Misbah in the Dubai Test, who I feel had read my googly but was still beaten. It gave me immense joy because Misbah was my state captain in Pakistan when I was a young leggie and despite knowing my bowling and despite having picked the wrong'un, he still went for the shot and was deceived.

Mushtaq: Nothing gave me more joy than watching a batsman who would be lured into attempting a drive against a googly which he could not read and the ball pierced through the gap between his bat and pad and hit the stumps. That was my best moment. My favourite dismissal remains the googly that beat Graeme Hick [lbw] in the 1992 World Cup final. I still enjoy watching that ball. Steve Waugh, if I'm not wrong, was bowled in the Sydney Test [1995-96] trying to drive. David Boon was clean bowled in the Rawalpindi Test [1994-95], again attempting a drive.

Tuesday, 20 October 2015

Adil Rashid's England leg-spin ignites the hopes of cricket's romantics

Vic Marks in The Guardian

All hail Adil Rashid! Not because he is suddenly the spinning messiah that we have all been craving since the retirement of Graeme Swann, but because he has survived.

Rashid will play in the next Test in Dubai and there should be a spring in his step. During his debut he probably had better things to do than wonder whether he might become England’s Bryce McGain, the Australian leg-spinner, who made his debut in Cape Town in 2009. It didn’t go frightfully well for Bryce, 18-2-149-0, though there must – in the manner of Chris Cowdrey – be a damn good after-dinner routine there somewhere.

It looked a bit bleak for Rashid after 34-0-163-0 in the first innings at Abu Dhabi – at least Bryce conjured a couple of maidens against South Africa. In these circumstances a Test match becomes an eternity. When will the next chance come around to make a contribution? But Rashid managed to hold his nerve. As he waited there was consolation in the fact that none of the other spinners were taking wickets. Then, when he was tossed the ball again, the batsmen were surprisingly under a bit of pressure; the ball gripped and once the hurdle of that first wicket had been leapt, something clicked to the tune of 5-64.

Whereupon leg-spinners around the world, whether amateur or professional, rejoiced – for they are a breed apart; they have a peculiar bond like wicketkeepers (“Do you want to have a look at my new inner gloves?” “Ooh, yes please.”) They recognise the tightrope that they have to walk every time the ball is tossed in their direction. By comparison finger-spinning is a low-risk doddle.

It is probably inadvisable for aspiring youngsters to study the history of English leg-spin since any research might persuade them to give up forthwith and bowl some medium-pacers instead. Last week the name of Tommy Greenhough of Lancashire was recalled for the first time in a while, since he was the last English leg-spinner to take five wickets in a Test match – in 1959.

Since then the specialists have been Robin Hobbs (12 wickets in seven Tests at 40 apiece), Ian Salisbury (20 wickets at 76 in 15 Tests), Chris Schofield (two Tests against Zimbabwe but no wickets) and Scott Borthwick, who has four wickets in his solitary Test at Sydney at an impressive average of 20, but who realistically is only likely to resurface at the top level if he bats in the first six. In the 60s there were the gifted casuals such as Bob Barber (42 wickets) and Ken Barrington (29), batsmen who could bowl. On this evidence there is not much encouragement for English wrist-spinners. Yet still leg-spinners prompt much wish fulfilment among the romantics.

There was great excitement when Salisbury took five wickets in his first Test match at Lord’s in 1992 against Pakistan, but that would be his best effort over the eight-year span of his Test career. Dear old Christopher Martin-Jenkins spent ages advancing his cause but in the end even he had to acknowledge that it wasn’t working. Salisbury, by the way, after coaching at county level for a while, is now doing some fine work with England’s Physical Disability Squad. He spoke movingly at the Cricket Writers’ lunch about how fulfilling this role was for him, let alone those he has been coaching.

There is the same yearning for Rashid to succeed. This is understandable, for wrist-spin is a glorious art to behold. The googly duping an unsuspecting batsman is a wonderful sight from most perspectives – though not all. Here writes a man, who padded up rather ineffectively to Abdul Qadir’s googly on his Test debut at Headingley only to hear the ball clunk on to off stump.

Later in Pakistan the mysteries of Qadir remained indecipherable. After a torrid time batting against him in a Test at Karachi, one journalist, Pat Gibson, who would become a valued colleague and guide, unkindly noted in his copy: “I don’t know what Marks read at Oxford … but it certainly wasn’t wrist spin.” Eventually I did score some runs against Qadir but only on flat, slow pitches later in the series – by adopting a West Country version of French cricket.

Qadir was a brilliant, exuberant bowler with all the varieties of the traditional wrist-spinner. The ball would fizz down often prompting this kind of thought process among callow batsmen. “Whoopee! He’s bowled me a full toss. Where shall I hit it? Hang on; it’s dipping. Not to worry. It’s a juicy half-volley. No problems here. Oh no … it keeps on dipping … where’s the damn thing going to pitch? Where’s it gone?”

The best spin bowlers obviously get the ball to turn off the pitch, but their greatest attribute is to make the ball dip in such a way that the batsmen cannot judge the length. Shane Warne in his pomp got the ball to swerve in to the right-hander menacingly. So did Qadir. And on a very good day so might Rashid. The extra spin that the wrist can impart enables the back of the hand men to find more “dip”. But this is such a difficult art to master.

I was impressed by Rashid when he was interviewed by Mike Atherton, another leg-spinner, after the game in Abu Dhabi. He was quite matter-of-fact, as if his Test match ordeal was a commonplace occurrence for a wrist spinner. He rejected the notion that he would have to bowl quicker in Test cricket (in fact he propels the ball at similar pace to Warne). And that sounded sensible to me. It might be lovely if Rashid could bowl at 53mph or more but the fact is that he has been bowling around the 47-49 mph mark throughout his career. That is his natural pace. It would make no sense for him to overhaul his method now because he has finally been promoted to Test level. Only the very best spinners can operate at significantly different paces according to the conditions.

For the moment Rashid has to stick to what he knows. Indeed for some bowlers it is almost impossible to change one’s natural pace significantly. This clearly applied to Monty Panesar, who was always less effective when he tried to bow to those yearning for him to bowl slower. In Dubai Rashid may be more relaxed now.

Meanwhile Alastair Cook is learning how best to use him. Rashid rarely operates as a stock bowler in the first innings of the match when playing for Yorkshire so he’s unlikely to be good at that for England against better players. Currently it is hard to imagine him as a solitary spinner in the Test team. We should not expect too much from him at this stage of his international career. This may make him seem like a luxury, someone who has to be protected sometimes. Hard-nosed coaches and pundits tend to be wary of such players – until the last two days of the game when the ball starts to misbehave and there’s a match to be won.

All hail Adil Rashid! Not because he is suddenly the spinning messiah that we have all been craving since the retirement of Graeme Swann, but because he has survived.

Rashid will play in the next Test in Dubai and there should be a spring in his step. During his debut he probably had better things to do than wonder whether he might become England’s Bryce McGain, the Australian leg-spinner, who made his debut in Cape Town in 2009. It didn’t go frightfully well for Bryce, 18-2-149-0, though there must – in the manner of Chris Cowdrey – be a damn good after-dinner routine there somewhere.

It looked a bit bleak for Rashid after 34-0-163-0 in the first innings at Abu Dhabi – at least Bryce conjured a couple of maidens against South Africa. In these circumstances a Test match becomes an eternity. When will the next chance come around to make a contribution? But Rashid managed to hold his nerve. As he waited there was consolation in the fact that none of the other spinners were taking wickets. Then, when he was tossed the ball again, the batsmen were surprisingly under a bit of pressure; the ball gripped and once the hurdle of that first wicket had been leapt, something clicked to the tune of 5-64.

Whereupon leg-spinners around the world, whether amateur or professional, rejoiced – for they are a breed apart; they have a peculiar bond like wicketkeepers (“Do you want to have a look at my new inner gloves?” “Ooh, yes please.”) They recognise the tightrope that they have to walk every time the ball is tossed in their direction. By comparison finger-spinning is a low-risk doddle.

It is probably inadvisable for aspiring youngsters to study the history of English leg-spin since any research might persuade them to give up forthwith and bowl some medium-pacers instead. Last week the name of Tommy Greenhough of Lancashire was recalled for the first time in a while, since he was the last English leg-spinner to take five wickets in a Test match – in 1959.

Since then the specialists have been Robin Hobbs (12 wickets in seven Tests at 40 apiece), Ian Salisbury (20 wickets at 76 in 15 Tests), Chris Schofield (two Tests against Zimbabwe but no wickets) and Scott Borthwick, who has four wickets in his solitary Test at Sydney at an impressive average of 20, but who realistically is only likely to resurface at the top level if he bats in the first six. In the 60s there were the gifted casuals such as Bob Barber (42 wickets) and Ken Barrington (29), batsmen who could bowl. On this evidence there is not much encouragement for English wrist-spinners. Yet still leg-spinners prompt much wish fulfilment among the romantics.

There was great excitement when Salisbury took five wickets in his first Test match at Lord’s in 1992 against Pakistan, but that would be his best effort over the eight-year span of his Test career. Dear old Christopher Martin-Jenkins spent ages advancing his cause but in the end even he had to acknowledge that it wasn’t working. Salisbury, by the way, after coaching at county level for a while, is now doing some fine work with England’s Physical Disability Squad. He spoke movingly at the Cricket Writers’ lunch about how fulfilling this role was for him, let alone those he has been coaching.

There is the same yearning for Rashid to succeed. This is understandable, for wrist-spin is a glorious art to behold. The googly duping an unsuspecting batsman is a wonderful sight from most perspectives – though not all. Here writes a man, who padded up rather ineffectively to Abdul Qadir’s googly on his Test debut at Headingley only to hear the ball clunk on to off stump.

Later in Pakistan the mysteries of Qadir remained indecipherable. After a torrid time batting against him in a Test at Karachi, one journalist, Pat Gibson, who would become a valued colleague and guide, unkindly noted in his copy: “I don’t know what Marks read at Oxford … but it certainly wasn’t wrist spin.” Eventually I did score some runs against Qadir but only on flat, slow pitches later in the series – by adopting a West Country version of French cricket.

Qadir was a brilliant, exuberant bowler with all the varieties of the traditional wrist-spinner. The ball would fizz down often prompting this kind of thought process among callow batsmen. “Whoopee! He’s bowled me a full toss. Where shall I hit it? Hang on; it’s dipping. Not to worry. It’s a juicy half-volley. No problems here. Oh no … it keeps on dipping … where’s the damn thing going to pitch? Where’s it gone?”

The best spin bowlers obviously get the ball to turn off the pitch, but their greatest attribute is to make the ball dip in such a way that the batsmen cannot judge the length. Shane Warne in his pomp got the ball to swerve in to the right-hander menacingly. So did Qadir. And on a very good day so might Rashid. The extra spin that the wrist can impart enables the back of the hand men to find more “dip”. But this is such a difficult art to master.

I was impressed by Rashid when he was interviewed by Mike Atherton, another leg-spinner, after the game in Abu Dhabi. He was quite matter-of-fact, as if his Test match ordeal was a commonplace occurrence for a wrist spinner. He rejected the notion that he would have to bowl quicker in Test cricket (in fact he propels the ball at similar pace to Warne). And that sounded sensible to me. It might be lovely if Rashid could bowl at 53mph or more but the fact is that he has been bowling around the 47-49 mph mark throughout his career. That is his natural pace. It would make no sense for him to overhaul his method now because he has finally been promoted to Test level. Only the very best spinners can operate at significantly different paces according to the conditions.

For the moment Rashid has to stick to what he knows. Indeed for some bowlers it is almost impossible to change one’s natural pace significantly. This clearly applied to Monty Panesar, who was always less effective when he tried to bow to those yearning for him to bowl slower. In Dubai Rashid may be more relaxed now.

Meanwhile Alastair Cook is learning how best to use him. Rashid rarely operates as a stock bowler in the first innings of the match when playing for Yorkshire so he’s unlikely to be good at that for England against better players. Currently it is hard to imagine him as a solitary spinner in the Test team. We should not expect too much from him at this stage of his international career. This may make him seem like a luxury, someone who has to be protected sometimes. Hard-nosed coaches and pundits tend to be wary of such players – until the last two days of the game when the ball starts to misbehave and there’s a match to be won.

Friday, 23 January 2015

Switching from pace to legspin

Nicholas Hogg in Cricinfo

Terry Jenner with Warne: it's all in how much you practise © Getty Images

Enlarge

When Brett Lee, my favourite pantomime villain of the 2005 Ashes series,announced his retirement from cricket, I admit I was sad. Firstly because any withdrawal of a player from the game they love is a melancholic day. The moment they hang up their boots, their career is nostalgia. The earth turns, and retirement is a marker of ageing - for players and spectators. And considering Lee was still launching missiles in the Big Bash, not forgetting his Piers Morgan rib-breakers last year, many of us were as surprised at the sudden timing.

Neither did it bode well for my first net of the year, last week. Now, I'm not for one microsecond comparing myself to Brett Lee. But as a medium-fast bowler who comes in off a full run I understand my days are numbered. This season I shall be 41. Lee is a puppyish 38, and he's already called it quits.

I was only halfway through my first ball of 2015 when I was wondering if I had marked out my run-up correctly. Surely it wasn't this far to the crease? And looking into the distance where the batsman stood, I doubted if the Lord's indoor school had got their measurements right. Although I eventually creaked into my delivery stride and that ball finally meandered the 22 yards towards the wicket, my body complained at every movement - that night, the next morning, and still now, nearly a week later I feel like the Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz.

So is it time to start my post-pace retirement? As I plan to play cricket until I can no longer take the field, I need a pension scheme that keeps me in good health.

Legspin is the long-term savings account I've been quietly paying into for most of my cricketing life. For nearly 30 years I've been swinging the ball away from a right-hand batsman, and legspin, a form I've experimented with since I first started bowling - particularly in ad hoc street games with non-swinging tennis balls - should be a natural switch, shouldn't it?

No. Not according to the BBC Sport Academy guide: "Learn to bowl leg spin". The web page begins with the foreboding "it may be the most difficult skill to master", and although it continues with a relatively simplistic "how to" diagram of grip positions and instruction, as well as confirmation that good legspinners get "bagfuls of wickets", any cricketer knows that bowling proper leggies is anything but easy.

The art of wristspin is confirmed as a subtle ability in the BBC's handy interactive guide by Shane Warne's former coach Terry Jenner, the man who, according to the website, "guided Warne to be the greatest leg spinner the world has ever seen". In each paragraph of instruction, Jenner uses the word "practice". Over and over again. With and without batsman. He urges young spinners - or students, as I prefer to call them, now that I'm enrolled in the legspin programme as a mature one - not to become disheartened when the batsman smashes the ball back over their heads.

"Spinners need a lot of love," Warne once said. "They need an arm around their shoulder to come back next week."

Legspin is the long-term savings account I've been quietly paying into for most of my cricketing life

In an effort to fast-track my learning I'm going to prepare by reading widely on the subject of legspin. Gideon Haigh's On Warne is an obvious choice, and I've just finished the introduction to Amol Rajan's Twirlymen - The Unlikely History of Cricket's Greatest Spin Bowlers.

From the opening paragraph of his treatise, Rajan, now editor of the Independent, admits that he really wanted to be a legspin bowler. His epiphany came when watching the Nine O'Clock News on June 3rd 1993 - a day Mike Gatting will never forget, either. The "ball of the century" that dipped and swerved and spun past the face of Gatting's hapless blade to nip the top of off stump changed Rajan's life.

Although Rajan's "generosity of boyhood girth" helped make his cricketing choices, it was the intellectual excitement of spin bowling that drew him to the art. And, as Warne's coach Jenner states, Rajan practised and practised until he forced his way into the Surrey Under-17s. Ultimately injury would force him from the game - this section I nervously skimmed over, as part of my legspin transformation is supposedly to stay healthy - and into journalism, but cricket's loss is media's gain.

Before starting this article I asked a Twitter question on who was the greatest ever legspinner. Warne, of course, topped the table, along with Qadir and Kumble close behind, with the notable vintage of players like Benaud and Bill O'Reilly respectfully mentioned. Most encouragingly, to a medium-pacer who is about to start the conversion, was a reply from Mike Atherton, who asked if he could present his two Test wickets for consideration. I say encouragingly because his brief and jokey answer hinted at the joy in wristspin, that bowling leggies won't be a quiet cricketing dotage but a new adventure.

Friday, 31 October 2014

Why are Asians under represented in English cricket?

by Girish Menon

A recent ECB survey found

that 30 % of the grass root level cricket players were of Asian origin while it

reduces dramatically to 6.2 % at the level of first class county cricketers. Why?

When this question was asked

to Moeen Ali, he opined among other things, "I also feel we lose heart too quickly. A lot of people

think it is easy to be a professional cricketer, but it is difficult. There is

a lot of sacrifice and dedication," While some may view Ali's views as

suffering from the Stockholm

syndrome, in my personal opinion it resembles the 'Lazy Japanese and Thieving

Germans' metaphor highlighted by the economist Ha Joon Chang. Hence, Ali's

views should not be confused with what in my perspective are some of the actual

reasons why there is a dearth of Asian faces in county cricket.

The

Cambridge

But

now that the economies of Japan ,

Korea and Germany

If

it wants the truth, English cricket should examine the issue raised by the

Macpherson report on 'institutional racism in the police' and ask if this is

true in county cricket as well. Immigrants, as the statistics suggest, from the

subcontinent can be found in large numbers in grassroots cricket from the time

they joined the British labour force. There are many immigrants only cricket

leagues in the UK , e.g in Bradford , where players of good talent can be found. But,

as Jass Bhamra's father mentioned in the film Bend it Like Beckham they have

not been allowed access to the system. Why, Yorkshire

waited till the 1990s to select an Asian player for the first time.

----Also read

----Also read

Failing the Tebbit test - Difficulties in supporting the England cricket team

----

Of

course, if the England

Secondly,

to make it up the ranks in English cricket it is essential to have an expensive

well connected coach. Junior county selections are based on this network and

any unorthodox talent would be weeded out at the earliest level either because

of not having a private coach or because the technique is rendered untenable as

it blots the copybook. So, many children of Asian origin from weaker economic

backgrounds are weeded out by this network.

This

is akin to the methods adopted by parents in the shires where grammar schools

exist. Hiring expensive tutors for their wards is the middle class way of

crowding out genuinely academic oriented students from weaker economic

backgrounds. Better off Asians are equally culpable in distorting the grammar school

system and its objectives.

So

what could be done. I think positive discrimination is the answer. We only need

to look at South African cricket to see what results it can bring. My

suggestion would be that every team should have two places reserved: one for a

minority player and another for an unorthodox player. This should to some

extent break up the parent-coach orthodoxy and breathe some fresh air and

dynamism into English cricket.

Personally,

I have advised my son that he should play cricket only for pleasure and not to

aspire for serious professional cricket because of the opacity in the selection

mechanism which means an uncertain economic future. He is 16, a genuine leg

spinner with little coaching but with good control on flight and turn. Often he

complains about conservative captains and coaches who were unwilling to gamble

away a few runs in the hope of getting wickets. Many years ago, when my son was

not picked by a county side, I asked the coach the reason and he said because,

'he flights the ball and is slower through the air'. With what conviction then could

I have told my lad that you can make a decent living out of cricket if you

persevere enough?

Sunday, 9 June 2013

The wasted talent of Danish Kaneria

Hassan Cheema in Cricinfo

The spot-fixing saga brought to an end a career that promised much - particularly in its infancy - but came to a cruel if fitting end. I am not talking about Sreesanth but about Danish Kaneria, the rejection of whose appeal could mean curtains for the man who was supposed to be Pakistan's next great spinner.

It's not that he didn't achieve much - after all, he finished with more Test wickets than any spinner in Pakistan's history - but how he did it. Somehow, one gets the feeling, that even if his career had wound up in different circumstances, there would not have been much celebration and nostalgia.

His likely sporting end calls to mind not just his own achievements and failings, but that of his generation. Pakistan's love affair with inexperienced youth reached its zenith in 1992, when a team comprising the likes of Inzamam-ul-Haq, Aamer Sohail and Moin Khan (each of whom had played less than 15 ODIs before the tournament started) walked off the MCG as world champions. It reinforced the national team's belief in inducting players far before they were ready, almost to save them from the much-maligned domestic first-class scene.

But as one generation gave way to another, there was a belated realisation that this induction required a national team full of leaders. The '92 generation succeeded because they came in with Javed Miandad, Imran Khan, Saleem Malik and Wasim Akram to guide them. One could argue that even the most celebrated players among those who debuted in the mid-to-late-90s (Shahid Afridi, Abdul Razzaq, Shoaib Akhtar and Mohammad Yousuf) could all have been so much more than they ended up being, however many great moments they provided. But even they can't hold a candle to the lot that debuted at the turn of the century - with Kaneria being probably the most obvious example among them.

It all goes back to a fateful day in 2003, when failure in the World Cup meant that the newly appointed chief selector, Aamer Sohail, brought the axe down upon the leaders of that team. Some would return, others (like Wasim, Waqar Younis and Saeed Anwar) wouldn't. And thus progress in many a career was ceased.

Among the 1999-2003 generation was a supremely fit fast bowler with natural outswing, who could bowl yorkers at will. And yet Mohammad Sami would finish as one of the worst bowlers of all time (statistically, at least). Similarly, Shoaib Malik threatened to be a genuine batting allrounder in the middle of the last decade, but is now more famous for who he married than anything he did on the field. Even Kamran Akmal, now the butt of all jokes, was once a wicketkeeper-batsman who could save and win matches, and was called by Ian Chappell "the best wicketkeeper in the world" in a piece of commentary that haunts many a Pakistani to this day. But no one better illustrates the unfulfilled potential of his generation quite like Kaneria does.

I was reminded of something Ramon Calderon, the then-president of Real Madrid, said in a typical outburst. He called Jose Maria "Guti" Gutierrez "the most promising 30-year old in the world". Guti was a star and vice-captain of the team at the time, and was labelled by Calderon as "the eternal promise". With half his career over, he had still not reached maturity or consistency in his play.