The art of stillness: Pico Iyer in TED

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label pace. Show all posts

Showing posts with label pace. Show all posts

Monday, 1 December 2014

Thursday, 20 February 2014

The psychological dominance of Mitchell Johnson

How do you stop Mitchell Johnson?

Beginning a post with that question naturally implies there is now going to be some kind of an answer. Well, there won't be one here, beyond the obvious, and that is that time will stop him, as time stops them all. He bowls with the ghosts of Larwood and Thommo and Holding and all of the other terrors behind him. (My own personal nightmare? Sylvester Clarke, the brooding Grendel of The Oval, who would come and knock on the hotel room doors of opposing batsmen to let them know exactly what he was about to do.) Johnson has, in a few short months, entered the realm of men who have exerted a strange psychological dominance with the overwhelming pace of their bowling.

The compelling aspects of the Johnson story lie there, because the hold he has is not just on batsmen, it is on the collective imagination of everyone watching him bowl. As Russell Jackson observed in the Guardian newspaper this week, each Johnson spell has become event television. The thrilling news the Centurion Test brought with it was that the Ashes was no one-off: if Johnson could do his thing away from home against Test cricket's best team, then it can happen anywhere to anyone. After a single game, there are echoes of what he did to England, which was to induce a kind of deep-rooted demoralisation that extended beyond the field and into the psyche (he was not playing alone, of course, but he was a spearhead). It was as if he had pulled out a pin that held the team and organisation together, and the unit just sprang apart - injury, illness, retirement, disharmony all had their way. - injury, illness, retirement, disharmony all had their way.

As the Cricket Australia Twitter account reported a little too gleefully - Ryan McLaren will miss the second Test with Johnson-induced concussion. There is also a run of luck that feels familiar: Dale Steyn stricken with food poisoning, Morne Morkel falling on his shoulder, and other phenomena not directly connected to Mitch but part of a general entropic slide. Just as England had players central to their strategy reaching the end of the road, so South Africa are absorbing the loss of Jacques Kallis: it's hard to think of a single player more difficult to replace. The captains of both teams happen to be left-hand openers, and Mitch is regularly decapitating both.

At the heart of all of this, as many have observed, is Johnson's pure and thrilling speed, channelled now into short and violent spells in which he bowls either full or short. This is the game reduced to its chilling basics. And yet there is mystery here too, and while unravelling it offers no answer to stopping Johnson, it may explain a little further what is causing such devastation.

The speed gun says that Johnson is bowling at speeds of up to 150kph, areas that other bowlers have touched. Because of the way in which speed guns work, deliveries of the sort that skulled Hashim Amla and Ryan McLaren registered more slowly due to where they pitched. (I'm sure that was great consolation to both players as the ball thudded into their heads.)

However, as the great Bob Woolmer revealed in his book The Art And Science Of Cricket, the nature of speed is not absolute because it is relative in the eyes of the batsman facing it. His research showed that the very best players - those who are euphemistically referred to as "seeing the ball early" - are actually reacting to a series of visual clues offered by the bowler in the moments before release.

Players who have faced Johnson speak of the sensation of the ball appearing "late" in his action, as his arm swings from behind his body. This is perhaps a combination of a couple of factors: the "clues" that Johnson offers in his run-up and delivery stride might be slightly less obvious than in other bowlers, and that his already ferocious pace is magnified by the extra micro-seconds that a batsman takes to pick the line and length of the ball (all the more impressive given that Johnson essentially only offers two lengths, and little variation on his themes).

Thus, with Mitch, the flexible nature of speed perception is working in his favour. Only the truly blessed - AB de Villiers, Kevin Pietersen et al - can play him with a little more certainty.

Pietersen was moved to tweet last week about the huge difference between 140kph and 150, just as his near-namesake Alviro was dismissed with a waft to the keeper. He said that you can "instinctively" play the wrong shot in those circumstances. What he was driving at was that Johnson offers no time for anything other than instinct, no margin to correct that first thought.

This is theory, of course. What can't be conveyed as easily is the psychological pressure that speed exerts. Players are wobbling to the crease with their minds consumed by thoughts of what he can do, and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. South Africa are on a slide that will take tremendous resolution, as well as skill, to stop. In Smith they have one of Test cricket's most redoubtable men, and in de Villiers and Amla two of the most sublimely talented. It is absolutely fascinating to watch, and Mitch has done the game a great service in his phoenix-from-the-flames revival. This is cricket at its sharpest physical and psychological point.

Monday, 6 January 2014

What's a good pitch anyway?

The 2013 Delhi Test was finished in three days. Ergo, was it a poor pitch? © BCCI

Enlarge

Cricket is one of those games where a question does not necessarily require a definitive answer. Merely exploring the parameters of the question provokes enough meaty debate to justify the question being asked in the first place. So on that basis, in the wake of the Ashes Test in Sydney, I pose this question: what defines a "good" Test pitch?

As this is a truly global forum, I expect a varied and sometimes passionate response from the four corners of the world. Assuming we can put aside the obvious patriotic bias, what are some of the qualities of a pitch that define it as good, bad or indifferent? Is it ultimately a question that can only be answered retrospectively, at the end of the game when the result is known, or is it possible to make a judgement call on it on the very first day (or relatively early in the match)?

Not long ago, a talkback caller on my weekly radio programme on the ABC was scathing in his criticism of all the pitches in India on Australia's most recent Test tour there, and similarly disdainful of most pitches in England on the last Ashes tour. When I pointed out some facts, he reluctantly conceded that his bias had been fed by lazy cricket writers who were looking for a populist audience, and we then enjoyed a more useful debate about how easy it was to succumb to an argument based on jingoism rather than cricketing knowledge.

So what defines a good pitch then? Is it a pitch where:

Plenty of runs scored at a rate of 3-plus?

Barring bad weather, a game reaches a conclusion some time after tea on day four?

Fast bowlers and spinners have equal opportunities to take wickets (proportionately of course, given that it's usually three quicks and one spinner)?

A few centuries but not too many are made?

The ball carries through to the keeper until about day four, after which uneven bounce becomes more prevalent? (And if there is no uneven bounce late in the game, is that a sign of a poor pitch?)

Conditions do not favour either side to any great extent (keeping in mind the accusations of "doctored" pitches sometimes levelled at home teams)?

The toss of the coin doesn't effectively determine the outcome of the match?

I personally believe home teams are entitled to prepare pitches to suit their strengths. It is up to the visitors to select a team that can cope with those conditions. If the game goes deep into day four and beyond, it suggests a relatively even contest, not necessarily in terms of an outright victor but at least the possibility of a draw. The common thinking that associates "good" with bounce, carry, pace is one of the great misnomers. Cricket's complex global appeal lies in the fact that trying to tame Mitchell Johnson at home on a bouncy deck is as much of a challenge as coping with wily New Zealand seamers on a greentop, or using your feet against three slow bowlers on a pitch that turns from the first day. The notion that it should do plenty for the fast bowlers through the match but shouldn't turn for the spinners from the outset is a theory clearly propounded by those unable to bowl spin or bat against it.

Let's look then at the most recent home Tests played by every country and leave it up to the readers to decide which of these Tests were played on "good" pitches. Remember that this is only a small sample size and invariably favours the home team, but is that enough of a reason to refer to the pitches as "doctored"? Don't most teams struggle to win away from home? In this list (below), not one visiting team won a game but how many of the local media outlets made excuses about "home-town" pitches?

Bangladesh v NZ, Mirpur. Match drawn. Bangladesh 282 all out, NZ 437 all out, Bangladesh 269 for 3. No play on day five.

Zimbabwe v Pakistan, Harare. Zimbabwe won by 24 runs. Zimbabwe 294 all out, Pakistan 230 all out, Zimbabwe 199 all out, Pakistan 239 all out. Match concluded just after lunch on day five.

West Indies v Zimbabwe, Dominica. West Indies won by an innings and 65 runs. Zimbabwe 175 all out, West Indies 381 for 8 decl, Zimbabwe 141 all out. Match concluded after lunch on day three.

Sri Lanka v Bangladesh, Colombo (Premadasa). Sri Lanka won by seven wickets. Bangladesh 240 all out, Sri Lanka 346 all out, Bangladesh 265 all out, Sri Lanka 160 for 3. Match concluded late on day four.

South Africa v India, Durban. South Africa won by ten wickets. India 334 all out, South Africa 500 all out, India 223 all out, South Africa 59 for 0. Match concluded after tea on day five.

England v Australia, London (The Oval). Match drawn. Australia 492 for 9 decl, England 377 all out, Australia 111 for 6 decl, England 206 for 5 (21 runs short). Match concluded day five, close of play.

India v West Indies, Mumbai. India won by an innings and 126 runs. West Indies 182 all out, India 495 all out, West Indies 187 all out. Match concluded before lunch on day three.

New Zealand v West Indies, Hamilton. New Zealand won by eight wickets. West Indies 367 all out, New Zealand 349 all out, West Indies 103 all out, New Zealand 124 for 2. Match concluded after lunch on day four.

Pakistan v Sri Lanka, Abu Dhabi. Match drawn. Sri Lanka 204 all out, Pakistan, 383 all out, Sri Lanka 480 for 5 decl, Pakistan 158 for 2. Match concluded day five, close of play.

Australia v England, Sydney. Australia won by 281 runs. Australia 326 all out, England 155 all out, Australia 276 all out, England 166 all out. Match concluded after tea on day three.

At first glance, I would nominate The Oval, Harare, Colombo and Durban as examples of excellent pitches, but does that necessarily make the others poor? Sydney, for example, barely lasted three days and clearly favoured the home team, but there should rightly be no talk of doctored pitches. England inspected the pitch, selected their best team, won the toss and were still thrashed by a vastly superior Australian outfit. Despite fine centuries from Steve Smith and Chris Rogers, 24 wickets fell on the first two days. Would the Australian media have been silent if that happened in Galle or Chennai? The resoundingly better team triumphed in Sydney, regardless of conditions that clearly favoured their strengths. Similarly when Australia toured India in 2013, despite winning all four tosses, they simply weren't good enough on pitches that suited India's skills. Delhi was the only venue that saw a result late on day three, and was labelled a disgrace by the Australian media, who will now be deafeningly silent about the early finish in Sydney, no doubt. Hence my earlier question - do we only judge a pitch retrospectively after we see who wins?

The recent Ashes series in England was written up by many in the Australian media as being played on "blatantly doctored pitches". Most of these cricket writers are journalists who never really played cricket to any significant level and are therefore sucked into the trap of making excuses that they think will resonate with readers who are supposedly dumb and easily seduced by an appeal to blind patriotism. But they misjudge us badly - the true Australian cricket fan understands the nuances of this great game and can appreciate skill, however it is wrapped, pace or spin. There will, of course, be that small vocal minority that only wants to read about good news (or excuses) but fortunately they are unlikely to be reading a global cricket website like this - the local tabloids will cater adequately to their coarse needs and hoarse voices.

Tuesday, 17 December 2013

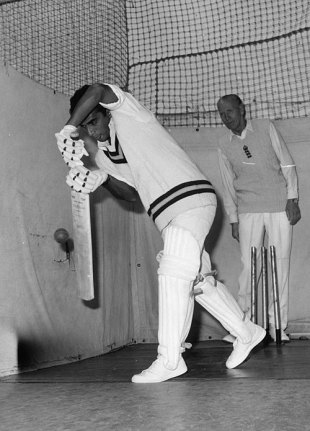

Cricket - The Gavaskar lesson on batting

The new breed of Indian batsmen need to carry the flame that Sunny, Sachin, and Rahul kept burning for so long

Martin Crowe in Cricinfo

December 17, 2013

| |||

Wisdom is priceless. When you get on a learning path, it is the best time of your life. Every day means something, every lesson provides the clarity you clamour for. You move forward, evolve, grow, and become more fulfilled as the big picture, the dream even, emerges from the shadows and into the light.

I will never forget the moments when I had the opportunity to acquire a touch of acumen, a piece of pure pansophy (Pansophism, in older usage often pansophy, is a concept of omniscience, meaning "all-knowing". In some monotheistic belief systems, a god is referred as the ultimate knowing spirit.). I was desperate to get a heads-up on life, especially about how to bat at the highest level. And so when I heard or saw that a walking encyclopedia on batting was nearby I went on a mission to trap the great man, whoever and wherever he was.

It started with meeting many fine players during my scholarship year at Lord's at age 17, under the watchful care of coach Don Wilson. I brushed up to Colin Cowdrey, Geoff Boycott, Fred Trueman and more, as Old England toured the land. Among the stories of endeavour they would tell were pearls of wisdom. It was an informal education on how to play the game.

When I returned a year later in 1982 and took up the groundsman-and-overseas-player role at Bradford's Park Avenue in North Yorkshire, I didn't quite realise how lucky I would be. When India played Yorkshire that summer, they did so on my patch and dubiously prepared pitch. This was where I met Sunil Gavaskar, one of the all-time greats and at the time the best player in the world alongside Viv Richards. I had to get inside this man's head, even if for a minute.

Being the groundsman gave me the chance. Over the four-day fixture I picked my moment and swooped like a vulture. "Sir, when playing the Windies, what is the single most important thing you must do to combat their pace and bounce?"

"Son, it's your eyes. Before I go out to bat, I find a wall and position into my stance with my right ear hard up against the wall. By doing this I feel my head and eyes level, my balance perfect, my feet light and ready to move. The wall is ensuring that I stay still. In the middle I pretend the wall is still there. Head position and balance. From there my eyes are in the best position to see the ball and to stay watching it until the shot is played."

Minutes later, back in the dusty shed, I found my wall. I could stand in position forever, my balance perfect. The mind and body got used to the balance, the more I did it. It was a lustrous piece of advice I never ever forgot. When my form dropped I went back to Gavaskar's elementary instruction.

Whenever I watched Sachin Tendulkar I thought he must have spoken to Sunny about the same thing, for Sachin always displayed a still, balanced stance and head position.

Now it's up to others to carry the torch. In the cauldron of South Africa it's up to a new breed of Indian batsmen to carry the baton that Sunny and Sachin did so incredibly, for so long.

These two men are not tall, so bounce was always their greatest enemy. Yet they trusted that if they saw the ball in a balanced position, with feet at the ready, they would move according to the movement of the ball, whatever shape that took. Eyes, then footwork. In that split second, once they saw the trajectory, the feet went to work, allowing the eyes to stay watching.

Dealing with bounce became just another obstacle, another movement to deal with. The key was their mental strength to clear the mind of any doubt, any second- guessing. When I first played West Indies, in Port-of-Spain, I assumed I needed to be ready a split second early, so I started moving before I saw the ball. I got 3 and 2 as Holding and Marshall easily trapped a moving, nervous target. It was a hopeless performance.

I went back to Sunny's sage advice and used the wall technique. A week later, in Georgetown, albeit on a flatter track that gave me a chance to build a more positive mindset, I batted so much better. After that I realised fully what Sunny had meant. It was the start of my international career proper.

| India's top five need to work out what shots are working for them and what shots are too risky. Importantly, they need to get a feel for the occasion | |||

Over the next month, against Steyn, Philander and Morkel, India can counter the home advantage, the pace and bounce, the second-guessing. Firstly, they must have a premise for success, and Sunny and Sachin, their master predecessors, have paved the way. They did it, and therefore it can be done again. They must draw upon that wisdom and apply it to their own game.

It takes courage to stay still with the head and trust the footwork when time is of the essence. You buy time when you see it early and play it late. It is when you see it late and play it early that the wheels fall off. Also, as Sunny, Sachin and Rahul Dravid proved, there are points where you have to be prepared to wear the opposition down, mentally and physically. You have to be patient. This way you can break it down to only the one ball that comes at you, one five-second block of concentration to deal with. Then another, and another.

Obviously, all this has to be done collectively, as a batting unit. The mind can deceive you when wickets are falling at the end, no matter how well you may have a grasp on your own situation. It has to be a combined commitment to fully embracing the challenge and working on the response.

Playing shots is important, as long as they are the right shots. You can't play them all. It's not like a T20 match. India's top five need to work out what shots are working for them and what shots are too risky. Importantly, they need to get a feel for the occasion, the opposition, the pitch, the air in which the ball travels quicker, especially in Johannesburg. They don't have much practice or time to get ready, given the nature of tours these days. So they must prepare in the mind and the imagination is perfectly equipped to provide a sense of calm within, before facing the heat in the middle.

For the top three, Dhawan, Vijay and Pujara, they only need to imagine Dravid in battle mode. He was the wall for a good reason. Rahul backed his eyes and his feet. For Rohit Sharma and Kohli it will be Sachin they can remind themselves of. These two icons showed time and again how it can be done, and those two learnt from Sunny, the master of compiling long innings against the might Windies.

Life is not about doing it alone. It's about learning from those who have already climbed great heights, and adding that history to one's own make up. Combining the love of the game and one's own ability with the wisdom of the ages is the essence of what we are here to do.

South Africa will throw all they have into these next two Tests. They are the No. 1 Test side by a long stretch. They have been messed around recently regarding this tour. They are highly motivated, there is no doubt. And they will steam in.

India need to provide the wall of resilience. Sunny used it, Sachin breathed it, Rahul was it. Kohli and Co can prosper by adding another brick in the wall of Indian batting mastery.

Friday, 13 December 2013

Why Mitchell Johnson fails the hipster test

Mitchell Johnson: not one to delight old-school fans © Getty Images

Enlarge

Over the past few weeks, the cricketing world has been agog at the achievements of Mitchell Johnson in the Ashes. There has already been talk that his performance in two matches merits him being rated the world's best bowler.

In digesting and reacting to this news, I realised that I was a fast-bowling hipster.

At its heart, the whole point of hipsters is not about being counter-culture, but rather laying claim to authenticity. You can't be a hipster if you jumped on a bandwagon or showed up without appreciating what you were there for. A hipster is authentic because an authentic experience means being there before it was cool and marketed. Consequently, while the rest of the world treats fast bowling as a seasonal fad, for Pakistanis it is more like l'bowling rapide pour l'bowling rapide.

As soon as I decided that I belonged to this ridiculous category, I realised I would need some codes to define what kinds of things fast-bowling hipsters, at least the ones from the Pakistani school of thought, would look for. The first person I turned to for inspiration was Osman Samiuddin, the high priest of the Pakistani fast-bowling cult. I remembered how he once related Shoaib Akhtar's reaction to Irfan Pathan: "Kaun Irfan? Saala spinner! Dekho ek cheez, paceispaceyaar. Can't beat it. [Irfan who? Damned spinner! Look here, paceispaceyaar. Can't beat it."]

Osman insists that in its true spirit, "paceispaceyaar" is one word, and so it is no surprise that pace - and an abundance of it - is the first sacrament of the fast-bowling hipster. Undoubtedly pace is at the heart of Johnson's prowess, and he manages to maintain his 90-plus speeds while bowling short. This means that he brings in the desire for mortal self-preservation into play in the batsman's psyche. This is a bowling tool so powerful that cricket has changed its laws to mitigate it.

Yet pace by itself means nothing - just take a look at Mohammad Sami, Fidel Edwards and a few others. A true fast bowler needs to develop all his skills with pace only as the foundation upon which they rest. Shoaib's point above is not about what Irfan can do with the ball, but rather that unless he is doing it at pace, he can't really be called fast. After all, paceispaceyaar.

The second major facet of this proposed manifesto is the bowling action and its aesthetic effect. I must qualify here that the aim is not to extol the virtues of textbook actions, since hipsters are not puritans. What the hipster looks for is a sense of uniqueness to the action. The sight of a bowler in full flight must be an intensely evocative experience, replete with a sort of hypnotic seduction and the ability to display vastly different facets of the action when watched at various speeds.

Take a look at the actions of Pakistan's great pantheon. Waqar Younis felt like a plastic footruler, bent outwards to its extremes before lithely snapping back. Wasim felt more like a snake that coiled up suddenly and narrowed its gaze before lashing out with a swift, fatal stab. The most majestic was Imran, who seemed to float like a bird of prey for several delicious moments, almost willing time to slow down before accelerating instantaneously.

Mitchell, though, is a slinger, from a breed of pacers who sometimes lack a sense of rhythm as well as lacchak (sway) that other actions provide. My favourite slinger was Shaiby (Shoaib Akhtar) , but a lot of his appeal had to do with his hyper-flexing elbows and the spectacle of his run-up. But the slinger ideal for hipsters would probably be Jeff Thomson, whose run-up was a bit bustly, but whose delivery stride and action were an absolute wonder to watch. Mitchell's run-up, in contrast, is quite stodgy, and he uses his bowling arm almost like an appendage that he hurls with rather than as an extension of a greater process.

This idea of synergy between the various facets is imperative, because it suggests both coherence and honesty. Many people have talked about Mitchell's new-found attitude and aggression, but it's not something I buy at all. Mitchell's wickets came while he was sporting a charity moustache during a particularly desperate and shrill search for redemption amongst the Australian media. In order to create a simple narrative, Mitchell was suddenly made out to be a bloodthirsty brute.

Mitchell's wickets came while he was sporting a charity moustache during a particularly desperate and shrill search for redemption amongst the Australian media. In order to create a simple narrative, Mitchell was suddenly made out to be a bloodthirsty brute

To me, this new perception of him is the latest example of cricket's habit of enforcing macho ideals on fast bowlers. For a long time, those in charge of cricket's narrative have tried to stereotype fast bowlers as a violent, angry, primitive lot. The appropriation of the shy Harold Larwood is the oldest example I can think of, but this has been repeated over time, and is patently unfair.

Mitchell himself has often been a victim of this desire to project alpha-male fantasies on pacers. For example, Michael Atherton once described listening to Johnson explaining his tattoos as similar to "listening to a warrior talk us through his flower arrangements before battle".

Despite my fondness for Atherton's writing, this opinion rankled, because I felt players like Johnson were needlessly criticised based on their personal choices. Who said that the leader of the attack needed to be some sort of medieval warrior? However, it now seems that Johnson has stopped trying to get people to understand that he is a soft-spoken, easy-smiling Australian who bowls fast, and is instead trying to look and act like a surfer masquerading as Merv Hughes.

Such charades are an affront to the hipster, since the persona of fast bowlers must be an organic part of their psyche. It is true that this translates into many pumped-up macho figures, but those are not the only kinds of demons a fast bowler has to deal with. In either case, for hipster appreciation eligibility, a fast bowler should never conform to what society deems desirable, but rather must force society to accept him on his own terms.

The third sacrament for the hipster is a cricket brain. This might well be the most important factor of them all, because it is the one thing that cannot be compensated for. For example, Glenn McGrath might have had a lot of vertical velocity and funny one-liners, but when he bowled, he looked like a grimacing elderly man trying very hard not to snap one of the metal pins in his replacement hip. Yet he remains one of the quintessential hipster choices, simply because of the suspense novels he wrote with his spells. Few other bowlers had his ability to not only predict what the batsman would do but also force him to willingly fall into the traps he had laid for him.

Mitchell Johnson's involvement with the psyche is so far limited to creating panic and fear. Now, that is not to be scoffed at, but as a Pakistani I have plenty of experience of watching panicked collapses, and like with Mitchell's wickets, these often come off poor deliveries. Take a look at his pitch maps from the two Tests and you see few deliveries pitched up, which means that there was little attempt at lulling players into false strokes or bamboozling them with movement.

Mitchell could claim that he didn't have to do anything more to pick off the English, and while he would be correct, the hipster cares not for such excuses. The hipster needs variety, needs elaborate plans, needs to see batsmen fail despite having tried their absolute best.

These three sacraments, or pillars, of the hipster faith can be represented as a set of stumps, and that brings us to the final point.

The Pakistani school of thought regarding fast bowling is inextricably linked to wickets, or more precisely, to flying, walking, cartwheeling wickets. Think of Waqar reversing the ball so rapidly and so late that you felt there had been a tear in space-time. Think of Wasim bowling round the wicket and taking the ball away to knock back off stump. It is the ultimate humiliation for the batsman, and a singular achievement for the bowler, who didn't need fielders to complete the job for him. In contrast, a catch at fine leg doesn't give the same sense of drama or spectacle.

Moreover, being able to bowl short is a luxury few teams afford their bowlers. For the hipster, then, being able to bowl short and fast isn't so impressive if all you have known growing up are fast and bouncy wickets. Bowling fast and full in a country and climate where there is no rational reason for doing so is what the hipster looks for, and that is why the Pakistani fast bowler has such a sense of romanticism attached to him.

So please don't offer me gentle souls dolled up in hairy costumes and tell me they are the real deal. Please don't insult cricket's answer to Keanu Reeves by pretending he's Sylvester Stallone. And please, please, please make sure to consult hipsters when jumping on your next bandwagon, so we can immediately tell you how wrong you are.

Tuesday, 4 June 2013

Cricket - On Medium Pace Spin

Amol Rajan in Cricinfo

| |||

It is a curious fact that when cricket was first becoming popular in England, in the latter half of the 18th century, all bowlers were either spinners or had great ambitions to be. This was because at the time bowling referred to the action we now associate with ten-pin bowling: rolling the ball along the surface of the earth, from bended knee, as if making a proposal of marriage to the distant batsman. A bowler's best hope during this, the dawn of the game, was for a molehill, foxhole, or adder enclave to impart deviation and so befuddle the batsman. When, finally, bowlers were allowed to give the ball air - probably around 1770 - their under-arm actions couldn't generate much pace. So they relied on spin.

All the reports, including those of John Nyren, author of cricket's first notable work of literature The Young Cricketer's Tutor, show that the earliest air bowlers, men such as Edward "Lumpy" Stevens and Lamborn, the "Little Farmer", used "twist" to break the ball from off to leg or, more commonly, leg to off. The round-arm and over-arm revolutions were many decades away alas, so bowling was a twirlyman's task. This pattern continued for so long that, rightly understood, the modern dominance of pace bowling is akin to a decades-long aberration from the norm. The history of mystery didn't leave much space for pace.

On July 15, 1822, a maverick named John Willes, who had been pushing the boundaries of the laws of the game for over a decade, bowled a round-arm delivery for Kent against MCC at Lord's. The umpires called no-ball. Willes threw the ball down in disgust, called for his horse and rode off into the sunset, scarcely playing again, so ostracised was he by cricket's fraternity. Little did he know that he had planted the seeds of a revolution that would catapult the game into modernity. In 1828, MCC moderated Rule 10 to allow the hand as high as the elbow; in 1835 another change allowed the arm up to shoulder height; in 1845 the benefit of the doubt was declared (as usual) against the bowler; and in 1864, the grand overlords of the game finally succumbed and declared over-arm bowling legal.

But then a funny thing happened, and kept happening for years. Rather than open the floodgates to a new breed of super-fast bowling tyrant, the dominant form of bowling right up to the inter-war period became something the like of which we hardly see in today's game, to the detriment of fans and players alike. In the late-Victorian period, all the most successful bowlers in the game were those who, rather than submit to an illusory need for speed, decided they could have the best of both worlds. They bowled spin, but at medium pace.

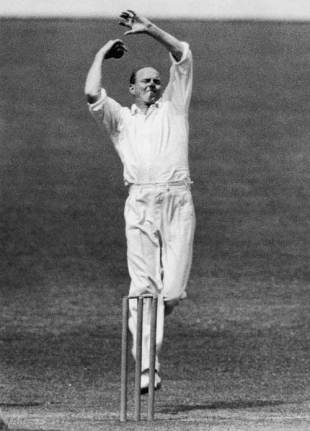

In England, three dominated: WG Grace, AG Steel, and George Lohmann. In Australia, a further three stood out: FR Spofforth, Monty Noble and Hugh Trumble. Each in turn pre-empted the rise, and extraordinary success, of the most complete bowler that ever lived, that cantankerous English rascal Sydney Barnes. He too was a medium-paced spinner. In fact, if you visit ESPNcricinfo and look to see who has the best career averages andbest strike-rate in Tests, you'll alight on Lohmann (with Barnes not too far behind). All of which rather begs a question: if medium-pace spin was so effective, why on earth did it die out?

Before answering that question, it may be worth establishing the credentials of these bowlers by focusing briefly on Barnes who, understood in the proper context, is really their apogee. The dashing county player Jack Meyer said Barnes was definitely quicker than Alec Bedser, which seems astonishing. My guess is that, depending on the pitch, Barnes would hit around 70 or even 75mph. If you're a club cricketer, that's probably up there with the fastest you've faced. CB Fry said of him that: "in the matter of pace he may be regarded either as a fast or fast-medium bowler. He certainly bowled faster some days than others; and on his fastest day he was distinctly fast."

And yet, as he brought his arm over, Barnes gave the ball an almighty rip. I'm not talking here about using seam and swing to extract cut from the pitch. I'm talking full-on spin, with a couple of special attributes. That is why John Arlott could say of Barnes: "He was a right-arm, fast-medium bowler with the accuracy, spin and resource of a slow bowler." Note that Arlott, who always chose his words carefully, describes Barnes not as medium or even medium-fast, but as fast-medium. And that he was a genuine, even prodigious, spinner of the ball is evidenced by Barnes' account of an extraordinary meeting with Noble.

| My guess is that, depending on the pitch, Barnes would hit around 70 or even 75mph. If you're a club cricketer, that's probably up there with the fastest you've faced | |||

Twirlymen constitute a special breed within cricket, a fraternity that bestows special privileges on its members, and through the ages spinners have met with each other to pass on the wisdom they have gleaned. Shane Warne and Abdul Qadir once sat across a Persian carpet from each other in the latter's house in Pakistan, spinning oranges hither and thither. Similarly, Barnes said he once asked Noble: "if he would care to tell me how he managed to bring the ball back against the swerve.

"He said it was possible to put two poles down the wicket, one 10 or 11 yards from the bowling crease and another one five or six yards from the batsman, and to bowl a ball outside the first pole and make it swing to the off-side of the other pole and then nip back and hit the wickets. That's how I learned to spin a ball and make it swing. It is also possible to bowl in between these two poles, pitch the ball outside leg stump and hit the wicket. I spent hours trying all this out in the nets."

For such a fastidious man, Barnes is rather lazy in conflating "swerve" and "swing" here. What he means by both is what we today refer to as "drift": the glorious tendency of a spinning ball to move in the air in the opposite direction to the eventual spin off the wicket. Unlike modern spinners, Barnes' wrist was slightly cocked back at the point of release, as if he was screwing or unscrewing a light bulb above his head (screwing for the offbreak; unscrewing for the legbreak). This, for reasons only a better physicist than I could tell you, compensates in accentuated swerve for what it sacrifices in turn off the wicket.

So the picture we have of the man who took 189 wickets in just 27 Tests at 16.43, with a wicket every seven overs - and a record 49 wickets in four Tests against South Africa in 1913-14 (he refused to play the last Test in a dispute over his wife's hotel fare) - is of genuine pace and genuine spin combined. He was perhaps quicker, and spun the ball more, than the other swift pioneers of the late-Victorian period. But is there any good reason that modern bowlers resolutely refuse to ape Barnes' astonishingly successful method? My answer is emphatically no.

It's true that there has been a conspiracy against spinners throughout the course of the game - shorter boundaries, limited overs, bigger bats, video replays (which cost them dearly until Hawk-Eye) came in and, above all, covered pitches. The last of these may partly explain the dwindling of the art. But there are three other possible reasons too: first, fashion; second, modern coaching; and third, sheer laziness.

None of these are forgivable, of course, particularly the needless and harmful conservatism of coaches who insist young players specialise early. Barnes had only three hours of coaching in his entire life. He would scoff at the refusal of fast bowlers to learn the art of spin, and vice versa; and if there is no good reason to keep the two art forms distinct, there must be hope that some brave young bowler could raise the spirit of medium-pace spin from the sporting grave to which it has prematurely been consigned. If he had the wit just to try, and the talent to come into mild success, lovers of the game the world over would be eternally in his debt for reacquainting cricket with a once great technique.

Wednesday, 8 May 2013

Cricket - Mallett on Grimmett and O'Reilly

The Tiger and the Fox

Bill O'Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett were the greatest spin-bowling partnership of their age, and arguably the best in Test history

Ashley Mallett

May 8, 2013

A

| |||

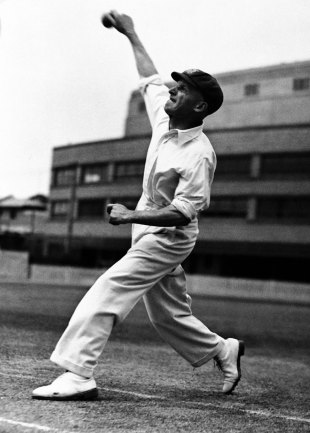

Between the world wars, Bill O'Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett reigned supreme. They were the greatest spin-bowling partnership of their age, and arguably the best in Test history. O'Reilly, the Tiger, and Grimmett, the Fox, were both legspinners but they approached their art as differently as Victor Trumper and Don Bradman approached batting.

Arms and legs flailing in the breeze, O'Reilly stormed up to the crease with steam coming out of his ears. He believed in all-out aggression, and called himself a "boots'n'all" competitor. Bradman, who reckoned O'Reilly to have been the best bowler he saw or played against, said he had the ability to bowl a legbreak of near medium pace that consistently pitched around leg stump and turned to nick the outside edge or the top of off.

"Bill also bowled a magnificent bosey which was hard to pick, and which he aimed at middle and leg stumps," said Bradman in a letter he wrote to me in 1989. "It was fractionally slower than his legbreak and usually dropped a little in flight and 'sat up' to entice a catch to one of his two short-leg fieldsmen. These two deliveries, combined with great accuracy and unrelenting hostility, were enough to test the greatest of batsmen, particularly as his legbreak was bowled at medium pace - quicker than the normal run of slow bowlers - making it extremely difficult for a batsman to use his feet as a counter measure. Bill will always remain, in my book, the greatest of all."

O'Reilly first came up against Bradman in the summer of the 1925-26 season, when Tiger's Wingello took on the might of Bradman's Bowral. Sixteen-year-old Bradman, who to his 19-year-old adversary was hardly any bigger than the outsized pads he wore, edged a high-bouncing legbreak straight to first slip when on 32. But the Wingello captain, Gallipoli hero Selby Jeffrey, was busy lighting his pipe, and the chance went begging.

Stumps were drawn with Bradman 232 not out, leaving the Tiger snarling in disbelief and raising his eyes to the heavens at the blatant injustice of it all. The game resumed the next Saturday afternoon. Bradman faced the first ball from the wounded Tiger. It pitched leg and took the top of off.

In the year O'Reilly came into this world, 1905, Grimmett tore a hole in his new blue suit, clambering over the barbed wire at Wellington's Basin Reserve to watch Trumper hit a famous hundred. In 1914, Grimmett sailed into Sydney from his native New Zealand, seeking cricketing fame. But it wasn't until a long stint in Sydney and more fruitless years in Melbourne before a last throw of the dice in Adelaide proved to be a haven for an unwanted bowler.

Grimmett began his Test career against England at the SCG in 1925, taking a match haul of 11 for 82. He starred in Australian tours of England in 1926 and 1930, but it was in the Adelaide Test of 1932, O'Reilly's debut, that the Tiger and the Fox first joined forces. Grimmett was the master and O'Reilly the apprentice, in a game that was a triumph for Bradman (299 not out) and Grimmett (14 for 199).

| It is virtually impossible to compare spinners from different eras, although most would agree the best three legspinners in Test cricket were Grimmett, O'Reilly, and Warne | |||

O'Reilly was amazed by the way Grimmett bowled: "I learned a great deal watching Grum [the nickname Bill always used for his spinning mate] wheel away. I watched him like a hawk. He was completely in control. His subtle change of pace impressed me greatly."

The pair played two Tests that series and two more in the Bodyline series of 1932-33, before O'Reilly took over as Australia's leading spinner when Grimmett was dropped. They were back in harness for the 1934 Ashes - the Tiger's first England tour, Grimmett's third. Here's O'Reilly on their unforgettable partnership:

"It was on that tour that we had all the verbal bouquets in the cricket world thrown at us as one of the greatest spin combinations Test cricket had seen. Bowling tightly and keeping the batsmen unremittingly on the defensive, we collected 53 [Grimmett 25, O'Reilly 28] of the 73 English wickets that fell that summer. Each of us collected more than 100 wickets on tour and it would have needed a brave, or demented, Australian at that time to suggest that Grimmett's career was almost ended."With Grum at the other end I knew full well that no batsman would be allowed the slightest respite. We were fortunate in that our styles supplemented each other. Grum loved to bowl into the wind, which gave him an opportunity to use wind-resistance as an important adjunct to his schemes regarding direction. He had no illusions about the ball 'dropping', as we hear so often these days, before its arrival at the batsman's proposed point of contact. To him that was balderdash. In fact, he always loved to hear people making up verbal explanations for the suspected trickery that had brought a batsman's downfall. If a batsman had thought the ball had dropped, all well and good. Grimmett himself knew that it was simply change of pace that had made the batsman think that such an impossibility had happened."

| |||

While O'Reilly was all-out aggression, Grimmett was steady and patient. They both possessed a stock ball that turned from leg. O'Reilly's deliveries came at pace: his legbreak spat like a striking cobra, and his wrong'un reared at the chest of the batsman. For any batsman in combat with the Tiger there was no respite, no place to hide.

In contrast, Grimmett wheeled away in silence. He was like the wicked spider, spinning a web of doom. Sometimes it took longer for him to snare his victim, but despite their vastly different styles and methods of attack they were both deadly. A batsman caught at cover off Grimmett was just as out as a man who lost his off stump to a ball that pitched leg and hit the top of off from O'Reilly.

Bradman once wrote me: "I always classified Clarrie Grimmett as the best of the genuine slow legspinners, (I exclude Bill O'Reilly because, as you say, he was not really a slow leggie) and what made him the best, in my opinion, was his accuracy. Arthur Mailey spun the ball more - so did Fleetwood-Smith and both of them bowled a better wrong'un but they also bowled many loose balls. I think Mailey's bosey was the hardest of all to pick.

"Clarrie's wrong'un was in fact easy to see. He telegraphed it and he bowled very few of them. His stock-in-trade was the legspinner with just enough turn on it, plus a really good topspin delivery and a good flipper (which he cultivated late in life). I saw Clarrie in one match take the ball after some light rain when the ball was greasy and hard to hold, yet he reeled off five maidens without a loose ball. His control was remarkable."

Grimmett invented the flipper, which Shane Warne, at the height of his brilliant career, bowled so well. Like Grimmett, Warne didn't have a great wrong'un, but he possessed a terrific stock legbreak and a stunning topspinner. When O'Reilly asked SF Barnes where he placed his short leg for the wrong'un, Barnes replied: "Never bowled the bosey… didn't need one."

Imagine if Grimmett and O'Reilly had played 145 Tests, the same number as Warne. At the rate they took their wickets, Grimmett would have snared a shade under 870 and O'Reilly 770. In reality Grimmett played just 37 Tests and O'Reilly 27, but what an impact they had on cricket. It is virtually impossible to compare spinners from different eras, although most would agree the best three legspinners in Test cricket were Grimmett, O'Reilly, and Warne.

The Tiger and the Fox were unique in their contrasting styles, but they had one thing in common: they were spin-bowling predators. Their prey was any batsman who ventured to the crease when they were on the hunt.

Saturday, 2 March 2013

On Spin Bowling in India - 'You have no idea what you're doing here'

Like other Australian spinners in India, Gavin Robertson finished his tour with a good idea of how to bowl there. Somehow the lessons keep getting lost

March 1, 2013

| |||

Sitting towards the back of a Bangalore function room in March 1998, Gavin Robertson and Steve Waugh shared a glum, quiet dinner. Australia had been overtaken by India in the first Test, in Chennai, and then obliterated in the second, at the Eden Gardens. Robertson's offspin had been toyed with, while Waugh was coming to terms with his first Test-series loss in four years. Noticing the duo away from the gathered dignitaries, the august figure of Erapalli Prasanna ventured over to join the New South Welshmen. By way of a greeting he offered the words: "You have no idea what you're doing here."

Robertson's mere presence in India had been a shock to many. Touring Pakistan in 1994, then opposing Waugh for Australia A in the World Series Cup of the following home summer, Robertson had drifted so far from international reckoning that in the summer preceding the India Tests, he had played only a solitary Sheffield Shield game for the Blues. In it, however, he had taken seven wickets at Adelaide Oval, keeping his name from sliding completely. Shane Warne's desire to be paired with a spinner in the vein of the retired Tim May, and some prodding from Waugh and Mark Taylor subsequently, had Robertson trading his day job managing grocery shelves for a six-week journey through India.

"I was only training two or three days a week, which I almost find hilarious," Robertson recalls. "I wasn't that physically fit, I would eat whatever I had to at work to do long days, and play grade cricket on Saturday. The next thing I knew, I was playing Test cricket in 84% humidity and 44C. I think I lost 8kg on the trip."

Perhaps not surprisingly, given his preparation, Robertson struggled to find the right method, though he fought admirably in Chennai, taking wickets and making stubborn lower-order runs. Despite the team's pre-eminence as the world's top-rated side, there was a lack of knowledge and understanding about India, a country most had visited once or twice at most - this was Warne's baked beans tour, after all.

"It was a rollercoaster three Tests. We didn't really know what we were doing in the first Test, and my pace was wrong, even though I took five wickets. What happened to me the Indians did to both myself and Shane Warne. Every time you'd bowl a good ball they negated it and waited for that patience to go, and then they really went after you. If you had a moment where you bowled two or three bad balls in an over, then you all of a sudden went for 12 or 16 runs. That's where the pressure builds."

So when Prasanna made his challenge about Australia's ignorance of India, Robertson found himself nodding. Waugh was a little more feisty, remonstrating with the man often considered the best of all India's offspinners, and author of the immortal slow-bowling maxim "Line is optional, length is mandatory." Perhaps throwing in a four-letter word or two for emphasis, Waugh asked Prasanna, "Well, if you know so much, how about you tell us?" What followed would change Robertson's tour.

"Prasanna talked about how you've got to understand a batsman," Robertson says. "You want to try to lock the batsman on the crease with the amount of spin you've got on the ball and your pace and dip. You've got to combine that to make sure the batsman feels like if he leaves his crease to take a risk, it's going to drop on him and he'll lose the ball.

"So he'll search quickly to defend, and that will cause him to feel nervous about leaving his crease, and that'll start to get him locked on his crease. Then you'll get him jutting out at the ball and jabbing at it with his hands. Then he'll start trying to use his pad and his bat together to negate a good ball. Finally he said, 'All you have to do is get that right pace and create that feeling, and then you have to do it for 20 or 30 overs in a row, and you'll bowl them out.'"

| "It's about finding the right pace and line that locks the batsman on the crease. If you can do it for long periods of time, you win the pressure battle, you break them down, you get wickets"Gavin Robertson | |||

Subtlety, discipline and consistency. These were not outlandish tactics, but they mirrored what Robertson had seen from his Indian counterparts, both in 1998 and on the tours to follow. Over the next few days before the third Test, in Bangalore, Robertson worked at this method, quickening his pace slightly and seeing useful results in the nets. By the time he came on to bowl again on the first morning of the match, his confidence was restored to a decent level. Flicking the ball from hand to hand, he thought of bowling a couple of tidy maidens before lunch then settling in for the afternoon.

Nathan Lyon is familiar with the sort of thing that happened next. Those two overs went for plenty, leaving Robertson's mind to race again. "I went to lunch with 0 for 31 off two and I thought, 'I'm in real trouble here,'" he says. "When I came back on after lunch Stephen [Steve Waugh] was at mid-off and I said 'I'm going to go for it here, I'm going to try to spin a bit harder and bowl a bit quicker.'

"I added two extra steps to my run-up, which I'd never done. I told myself to bowl like a medium-pace offspinner - you bowl with a quicker arm action and actually get more on the ball. I bowled to Tendulkar and he came forward, it gripped and it spun, went past him, nearly hit Ian Healy in the head and went for four byes.

"I just kept doing it. I went from 0 for 31 off two overs to 2 for 58 off 11.2 overs, and in the second innings I took 3 for 28 off 12 and we won the Test. Those were the lessons. It sounds quite simple, but it's having the experience and the patience to keep doing it. They're not worried about you unless you bowl really well."

Robertson's awakening to what was required to bowl spin effectively in India is a tale that is true for many Australian spin bowlers who have ventured to the subcontinent. Robertson describes it as cases of "failure, failure, then some success by the time you go home". Jason Krejza was all but a lost cause on the 2008 trip until he worked with Bishan Bedi in the Delhi nets, and subsequently harvested 12 wickets - albeit expensive ones - in Nagpur. Nathan Hauritz was never able to settle in 2010 as he entered the tour after injury and then had his bowling style changed, not by the locals but by Ricky Ponting, who desired his tweaker to "bowl more like Harbhajan Singh", whatever that meant. None were granted a second chance to tour India and use the knowledge gained on the earlier visit.

"You could almost have all those learnings on a whiteboard or some sort of document that relays 'This is the plan for this, we know what we've been up against before, knock it over,'" Robertson says. "That's what I thought we were supposed to be doing when we went two and half weeks early. We probably haven't learned from those past tours."

For now, Lyon is trying to work out how best to succeed in Hyderabad, having taken four wickets in Chennai but at an enormous cost. Robertson recalled Prasanna's advice, but also the example set by R Ashwin and Ravindra Jadeja in Chennai.

"Have a look at the pace the Indian bowlers bowled at in the first Test," he says. "Just over, say, an hour or 15-over period, and watch how many times they're full and they're up outside off stump and spinning back. And then watch us and see how many times in that period we get short and get worked. How many times do we get scored off short balls, and how many times the other way?

"The Indians always bowl full with the right pace, the ball is dropping at sufficient pace and there's not enough time to get down the wicket to it. In Australia, Nathan Lyon can bowl on middle stump and a little bit short. Because the wickets are so quick here, it's so much harder for a batsman to punish it. Over there it's so slow, as soon as you bowl too short and on the wrong line, it just sits up like a cherry and it goes.

"It's about finding the right pace and line that locks the batsman on the crease. If you can do it for long periods of time, you win the pressure battle, you break them down, you get wickets."

Prasanna could not have said it better himself.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)