By Scott Oliver in Cricinfo

Former England offspinner Pat Pocock recalls his career: escaping rioters in Guyana, being mentored by Jim Laker, and captaining Sylvester Clarke

Pat Pocock (left), as Surrey's deputy president in 2014, presents certificates to members who had been with the club for 60 or more years © PA Photos

Pat Pocock (left), as Surrey's deputy president in 2014, presents certificates to members who had been with the club for 60 or more years © PA Photos

Taking seven wickets in 11 balls was a complete freak. Every time they nicked it, it went to hand; every time they played across the line, they were out lbw; every time it went in the air, it was caught. I can honestly say that I bowled much better in a match against West Indies in Jamaica, on a rock-hard wicket that was like marble and with a 55-yard boundary straight, when I bowled 50-odd overs and got 0 for 152. Every player in our side came up to shake my hand in our dressing room because I bowled so well.

Colin Cowdrey was a lovely man, a fine player, but he was not the strongest of characters and was very, very easily influenced as captain.

If I had to choose between sidespin and bounce, I'd pick bounce every time.

I played in Manchester against a very strong Australian side - Bill Lawry, Ian Chappell, Doug Walters, Ian Redpath, Bob Cowper, Paul Sheahan, Barry Jarman - a fabulous side. I bowled 33 overs, 6 for 79, and I'm left out the next game. I'd just turned 21. I thought: what way is that to bring on a young spinner? They brought Derek Underwood in.

John Woodcock said that the three people in the world he'd seen that enjoyed the game the most were Derek Randall, Pat Pocock and Garry Sobers.

A few years ago a guy came up to me and said, "I've got a night at the Royal Albert Hall in September. Do you fancy doing the opening spot?" It was blacked out, with two pin-spot lights into the middle of the stage. "Ladies and Gentlemen, please welcome former Surrey and England cricketer, Pat Pocock." I walk out - 3000 people there, black-tie job - and sang "For Once in Your Life" by Frank Sinatra. That gave me a bigger buzz than playing in front of 100,000 at Eden Gardens.

Getting knocked out by Unders was no crime, but in those days he was nowhere near the bowler that he became. In those days, they used to have the Man-of-the-Match awards split into two parts: bowler of the match and batsman of the match. Basil D'Oliveira won the batsman of the match and I won the bowler of the match [in Manchester]. We come to the next Test at Lord's and we were both left out of the side.

Jim Laker and Tony Lock were great bowlers, but the thing that made them even greater was, they bowled on hugely helpful wickets. Not only uncovered wickets but underprepared wickets as well. They turned square. They were masters of their craft, but even more so because of the pitches they played on. You had Laker and Lock, [Alec] Bedser and [Peter] Loader - great bowlers, bowling on result wickets, backed up with good batting, and because of that, Surrey won seven championships on the trot.

"The most unfortunate thing about my career was that I didn't play a single Test match between the ages of 29 and 37" © PA Photos

"The most unfortunate thing about my career was that I didn't play a single Test match between the ages of 29 and 37" © PA Photos

I got Sobers out nine times, but never in Test matches. I'd have liked to have got him out in a Test match.

I went over to Transvaal, only for one season, just to see the country. I enjoyed it enormously. The cricket was very strong; a bit lopsided - I didn't see many spinners - but lots of quick bowlers and batsmen.

A great big thick stone hit Tony Lock on the back of the head in Guyana [in 1967-68]. We'd just won the series and the crowd were rioting. Gold Leaf, the sponsors, were providing transport. I was with Locky and John Snow, and when the car eventually got through the crowd, there was a hail of bricks and sticks and pebbles and all sorts. We got in and the driver put his hand on the horn and drove straight at the crowd, with everyone leaping out of the way. We got about 100 yards before we stopped in the middle of more rioters throwing missiles toward the ground, thinking the players were still there. We were actually right in the middle of them, and we all slipped down under the seats and carried on.

The best three players I bowled at were Richards, Richards and Sobers. Barry first, then Viv.

I was one of the bigger spinners of the ball in the country. I used to bowl "over the top", so I made the ball bounce a lot. If you put spin and bounce, with control, into your skill set, then you're going to do well on good wickets.

The most unfortunate thing about my career was that I didn't play a single Test match between the ages of 29 and 37. If you interview any spinner that played for a long time, they'll tell you those were their prime years. When I was in the best form of my life, I didn't get picked.

I never got out as nightwatchman for England, and I'm quite proud about that.

Day in, day out, in county cricket, Fred Titmus was the best offspinner I ever saw. He was a fantastic bowler, with control and flight and a good swinger. But in Test matches, because he wasn't a big spinner of the ball - and bearing in mind you played on pitches that were prepared for five days, not three - you didn't often have to worry about Fred.

Since I was about five, I can't ever remember thinking I wanted to do anything else except play cricket. But all I was at five was keen. It was only about 12 when I thought perhaps I had a chance of playing professionally.

Pocock is congratulated for taking a wicket in Barbados, 1967-68 © Getty Images

Pocock is congratulated for taking a wicket in Barbados, 1967-68 © Getty Images

I was very lucky. If you think that the average person in the England side today has probably played between 70 and 100 first-class matches - I played 554, so that's quite a lot.

I had four people who helped me on my way up: Laker, Lock, Titmus and Lance Gibbs. Among them they had 7500 first-class wickets. I had lots of help and advice. Who have the players got today? Is it surprising we've barely got a spinner good enough for Test cricket?

Mike Brearley was the best captain I played under, but the person I most enjoyed playing under was David Gower, by far. When I played under David, I'd had over 500 first-class matches. He knew that I knew more about my bowling, and offspin bowling generally, than he would ever know, so he just let me get on with it. I didn't want to have to fight my captain to get the field I wanted.

The most important part of your body for deceiving the batsman in the flight is your wrist. The wrist is a forgotten area of spin bowling.

When I was first picked for England I was very much aware that there were a lot of senior players around. There haven't been too many times in English cricket history when there were more great players in the side: Colin Cowdrey, Kenny Barrington, John Edrich, Geoff Boycott, Tom Graveney, Jim Parks, Alan Knott, John Snow.

Dougie Walters was a very difficult player to bowl at for a spinner.

I was Titmus' understudy. He was a quality bowler, but on that [1967-68 West Indies] tour he didn't bowl very well. I played against the Governor's XI, virtually the Test team, and got six wickets for not many runs. Then I played against Barbados, who had nine Test players in their side, and got another six wickets. Suddenly all the press are writing: Is Pat Pocock going to get preferred to Fred? I thought I might be in line for a debut, and then of course he had the accident.

Apart from Illy [Ray Illingworth], there's no other offspin bowler who's played more first-class matches than me.

Playing in Madras in '72-73, I bowled a slightly short ball to Ajit Wadekar, who got back and cut it for four. Next over, I bowled another one, slightly short, turned slowly, and again he cuts it square. I said to Tony Lewis, the skipper, "I want a man out on the leg side in the corner." He said, "But he's just hit you for two fours square!" I said, "I know, but I'm not going to give him any more balls to hit. I'm going to bowl a stump straighter and a yard fuller, but if I do, I want that fielder out there." He started to grumble and shake his head. It was his third Test match and I'd played a couple of hundred first-class matches. I said, "Don't argue. Just f****** do it. I've got a reason."

The best offspinner I've ever seen, on Test match wickets, was Gibbs, because the spin and bounce he got were second to none. He'd always hit the shoulder or splice of the bat.

Pocock sings to spectators after a county day's play at The Oval © PA Photos

Pocock sings to spectators after a county day's play at The Oval © PA Photos

I didn't ever want to play for any other county, but if I had done, I'd have liked to have played for Glamorgan - not only because I was born in Wales but when you play for them you feel as though you're playing for more than a county. You feel as though you're playing for a country.

Sylvester Clarke was the most feared man in world cricket. Viv Richards went into print saying he didn't like facing him. Viv says he didn't wear a helmet. He bloody did: he wore one twice against Surrey when Sylvester Clarke was playing. Fearsome, fearsome bowler. I played against Roberts, Holding, Daniel, Garner, Marshall, Patterson, Walsh, Ambrose - all of them. I faced Sylvs in the nets on an underprepared wicket, no sightscreen, no one to stop him overstepping. There was nobody as fearsome as Clarkey was. And everybody knew it.

I captained Surrey because I felt I had to. I'd done it 11 years before I was given the official captain's job. I enjoyed the game too much and I didn't want anything to take my enjoyment away. But I looked around and thought there was no one else who could do it. We came second, which isn't too bad, although I did have a guy called Sylvester Clarke up my sleeve.

Laker became a good friend. We worked together on commentary. He didn't come up to me and say, "You've got to do this, you've got to do that", but a few times a situation would arise and he'd come up and make a suggestion.

In the first two-thirds of my career, The Oval was a slow, nothing wicket. You could hardly ever, as a spinner, get the ball to bounce over the top of the stumps. A nightmare. It was the slowest thing you could possibly bowl on. If it did turn, it hit people halfway up the front leg. Then they relaid all the surfaces and it went from one of the slowest, lowest pitches to this rock-hard thing that didn't get off the straight. We even had a stage with Intikhab [Alam] playing and he couldn't get it off the straight. Sometimes we played county games twice on the same pitch to try and get it to turn.

Greigy [Tony Greig] was the only player in the side who'd have done that [run out Alvin Kallicharran in Guyana]. Umpire Douglas Sang Hue had no option but to give him out. He hadn't called time and he hadn't picked the bails up. There were a few in the side that thought it was beyond the pale, but no one said it. Sobers told Greigy he should leave the ground in his car with him, otherwise he might not make it back to the hotel in one piece.

In Karachi, the students burned down the pavilion while we were still inside. The match and tour were called off.

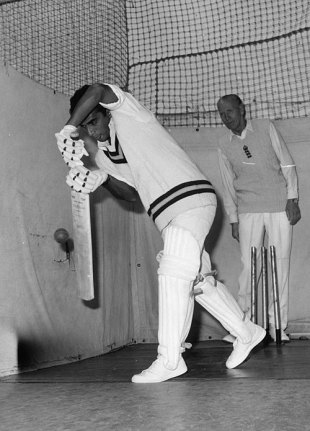

"I I never got out as nightwatchman for England, and I'm quite proud about that" © Getty Images

"I I never got out as nightwatchman for England, and I'm quite proud about that" © Getty Images

Tom Graveney playing a T20 game would be like entering a Rolls-Royce in a stock car race.

I got 1607 wickets and John Emburey got 1608, both at 26 apiece, but he bowled 2000 more overs to get that wicket. His home ground was Lord's, which, in those days, was an infinitely better place to bowl spinners than The Oval. He was a fine bowler, but he was defensive and I was attacking, and on some wickets I felt I had the edge over him.

One year, Boycott had got 1300 runs in nine innings. We were playing Yorkshire at Bradford, and I had Graham Roope on Boycott's shoelaces on the off side, right on top of him. I ran up, bowled him off stump. As he walked past Roopey, he said, "I can't play that bowling, me." Roopey told me that, and I said, "Roopey, that ball did absolutely nothing. It didn't drift, didn't turn, he just played inside the line."

As soon as I'd played representative cricket for England Schools - I used to bat No. 5 - I thought I might have a chance.

Kenny [Barrington] was a selfish player, but anyone who played like he did was always going to be more consistent than someone like Ted Dexter. He used to restrict himself to three shots, and that's why he didn't get out, whereas Ted played every shot in the book. Kenny's going to be more consistent, but Dexter will win you more games.

Closey [Brian Close] got one run in 59 minutes [at Old Trafford in 1976] and had the shit knocked out of him. He was in a terrible state when he came in. I got in as nightwatchman in the second innings and I didn't get out that night. Next morning, I'm walking out with John Edrich and he asked me, "Which end do you fancy?" I told him I'd have Andy Roberts' end as he was a bit of light relief. John pisses himself laughing: "I tell you now, if Andy Roberts is light relief then we've got problems."

-----Further inputs from Pat Pocock when asked what he meant by the use of the wrist in spin bowling:

Pat Pocock (left), as Surrey's deputy president in 2014, presents certificates to members who had been with the club for 60 or more years © PA Photos

Pat Pocock (left), as Surrey's deputy president in 2014, presents certificates to members who had been with the club for 60 or more years © PA PhotosTaking seven wickets in 11 balls was a complete freak. Every time they nicked it, it went to hand; every time they played across the line, they were out lbw; every time it went in the air, it was caught. I can honestly say that I bowled much better in a match against West Indies in Jamaica, on a rock-hard wicket that was like marble and with a 55-yard boundary straight, when I bowled 50-odd overs and got 0 for 152. Every player in our side came up to shake my hand in our dressing room because I bowled so well.

Colin Cowdrey was a lovely man, a fine player, but he was not the strongest of characters and was very, very easily influenced as captain.

If I had to choose between sidespin and bounce, I'd pick bounce every time.

I played in Manchester against a very strong Australian side - Bill Lawry, Ian Chappell, Doug Walters, Ian Redpath, Bob Cowper, Paul Sheahan, Barry Jarman - a fabulous side. I bowled 33 overs, 6 for 79, and I'm left out the next game. I'd just turned 21. I thought: what way is that to bring on a young spinner? They brought Derek Underwood in.

John Woodcock said that the three people in the world he'd seen that enjoyed the game the most were Derek Randall, Pat Pocock and Garry Sobers.

A few years ago a guy came up to me and said, "I've got a night at the Royal Albert Hall in September. Do you fancy doing the opening spot?" It was blacked out, with two pin-spot lights into the middle of the stage. "Ladies and Gentlemen, please welcome former Surrey and England cricketer, Pat Pocock." I walk out - 3000 people there, black-tie job - and sang "For Once in Your Life" by Frank Sinatra. That gave me a bigger buzz than playing in front of 100,000 at Eden Gardens.

Getting knocked out by Unders was no crime, but in those days he was nowhere near the bowler that he became. In those days, they used to have the Man-of-the-Match awards split into two parts: bowler of the match and batsman of the match. Basil D'Oliveira won the batsman of the match and I won the bowler of the match [in Manchester]. We come to the next Test at Lord's and we were both left out of the side.

Jim Laker and Tony Lock were great bowlers, but the thing that made them even greater was, they bowled on hugely helpful wickets. Not only uncovered wickets but underprepared wickets as well. They turned square. They were masters of their craft, but even more so because of the pitches they played on. You had Laker and Lock, [Alec] Bedser and [Peter] Loader - great bowlers, bowling on result wickets, backed up with good batting, and because of that, Surrey won seven championships on the trot.

"The most unfortunate thing about my career was that I didn't play a single Test match between the ages of 29 and 37" © PA Photos

"The most unfortunate thing about my career was that I didn't play a single Test match between the ages of 29 and 37" © PA PhotosI got Sobers out nine times, but never in Test matches. I'd have liked to have got him out in a Test match.

I went over to Transvaal, only for one season, just to see the country. I enjoyed it enormously. The cricket was very strong; a bit lopsided - I didn't see many spinners - but lots of quick bowlers and batsmen.

A great big thick stone hit Tony Lock on the back of the head in Guyana [in 1967-68]. We'd just won the series and the crowd were rioting. Gold Leaf, the sponsors, were providing transport. I was with Locky and John Snow, and when the car eventually got through the crowd, there was a hail of bricks and sticks and pebbles and all sorts. We got in and the driver put his hand on the horn and drove straight at the crowd, with everyone leaping out of the way. We got about 100 yards before we stopped in the middle of more rioters throwing missiles toward the ground, thinking the players were still there. We were actually right in the middle of them, and we all slipped down under the seats and carried on.

The best three players I bowled at were Richards, Richards and Sobers. Barry first, then Viv.

I was one of the bigger spinners of the ball in the country. I used to bowl "over the top", so I made the ball bounce a lot. If you put spin and bounce, with control, into your skill set, then you're going to do well on good wickets.

The most unfortunate thing about my career was that I didn't play a single Test match between the ages of 29 and 37. If you interview any spinner that played for a long time, they'll tell you those were their prime years. When I was in the best form of my life, I didn't get picked.

I never got out as nightwatchman for England, and I'm quite proud about that.

Day in, day out, in county cricket, Fred Titmus was the best offspinner I ever saw. He was a fantastic bowler, with control and flight and a good swinger. But in Test matches, because he wasn't a big spinner of the ball - and bearing in mind you played on pitches that were prepared for five days, not three - you didn't often have to worry about Fred.

Since I was about five, I can't ever remember thinking I wanted to do anything else except play cricket. But all I was at five was keen. It was only about 12 when I thought perhaps I had a chance of playing professionally.

Pocock is congratulated for taking a wicket in Barbados, 1967-68 © Getty Images

Pocock is congratulated for taking a wicket in Barbados, 1967-68 © Getty ImagesI was very lucky. If you think that the average person in the England side today has probably played between 70 and 100 first-class matches - I played 554, so that's quite a lot.

I had four people who helped me on my way up: Laker, Lock, Titmus and Lance Gibbs. Among them they had 7500 first-class wickets. I had lots of help and advice. Who have the players got today? Is it surprising we've barely got a spinner good enough for Test cricket?

Mike Brearley was the best captain I played under, but the person I most enjoyed playing under was David Gower, by far. When I played under David, I'd had over 500 first-class matches. He knew that I knew more about my bowling, and offspin bowling generally, than he would ever know, so he just let me get on with it. I didn't want to have to fight my captain to get the field I wanted.

The most important part of your body for deceiving the batsman in the flight is your wrist. The wrist is a forgotten area of spin bowling.

When I was first picked for England I was very much aware that there were a lot of senior players around. There haven't been too many times in English cricket history when there were more great players in the side: Colin Cowdrey, Kenny Barrington, John Edrich, Geoff Boycott, Tom Graveney, Jim Parks, Alan Knott, John Snow.

Dougie Walters was a very difficult player to bowl at for a spinner.

I was Titmus' understudy. He was a quality bowler, but on that [1967-68 West Indies] tour he didn't bowl very well. I played against the Governor's XI, virtually the Test team, and got six wickets for not many runs. Then I played against Barbados, who had nine Test players in their side, and got another six wickets. Suddenly all the press are writing: Is Pat Pocock going to get preferred to Fred? I thought I might be in line for a debut, and then of course he had the accident.

Apart from Illy [Ray Illingworth], there's no other offspin bowler who's played more first-class matches than me.

Playing in Madras in '72-73, I bowled a slightly short ball to Ajit Wadekar, who got back and cut it for four. Next over, I bowled another one, slightly short, turned slowly, and again he cuts it square. I said to Tony Lewis, the skipper, "I want a man out on the leg side in the corner." He said, "But he's just hit you for two fours square!" I said, "I know, but I'm not going to give him any more balls to hit. I'm going to bowl a stump straighter and a yard fuller, but if I do, I want that fielder out there." He started to grumble and shake his head. It was his third Test match and I'd played a couple of hundred first-class matches. I said, "Don't argue. Just f****** do it. I've got a reason."

The best offspinner I've ever seen, on Test match wickets, was Gibbs, because the spin and bounce he got were second to none. He'd always hit the shoulder or splice of the bat.

Pocock sings to spectators after a county day's play at The Oval © PA Photos

Pocock sings to spectators after a county day's play at The Oval © PA PhotosI didn't ever want to play for any other county, but if I had done, I'd have liked to have played for Glamorgan - not only because I was born in Wales but when you play for them you feel as though you're playing for more than a county. You feel as though you're playing for a country.

Sylvester Clarke was the most feared man in world cricket. Viv Richards went into print saying he didn't like facing him. Viv says he didn't wear a helmet. He bloody did: he wore one twice against Surrey when Sylvester Clarke was playing. Fearsome, fearsome bowler. I played against Roberts, Holding, Daniel, Garner, Marshall, Patterson, Walsh, Ambrose - all of them. I faced Sylvs in the nets on an underprepared wicket, no sightscreen, no one to stop him overstepping. There was nobody as fearsome as Clarkey was. And everybody knew it.

I captained Surrey because I felt I had to. I'd done it 11 years before I was given the official captain's job. I enjoyed the game too much and I didn't want anything to take my enjoyment away. But I looked around and thought there was no one else who could do it. We came second, which isn't too bad, although I did have a guy called Sylvester Clarke up my sleeve.

Laker became a good friend. We worked together on commentary. He didn't come up to me and say, "You've got to do this, you've got to do that", but a few times a situation would arise and he'd come up and make a suggestion.

In the first two-thirds of my career, The Oval was a slow, nothing wicket. You could hardly ever, as a spinner, get the ball to bounce over the top of the stumps. A nightmare. It was the slowest thing you could possibly bowl on. If it did turn, it hit people halfway up the front leg. Then they relaid all the surfaces and it went from one of the slowest, lowest pitches to this rock-hard thing that didn't get off the straight. We even had a stage with Intikhab [Alam] playing and he couldn't get it off the straight. Sometimes we played county games twice on the same pitch to try and get it to turn.

Greigy [Tony Greig] was the only player in the side who'd have done that [run out Alvin Kallicharran in Guyana]. Umpire Douglas Sang Hue had no option but to give him out. He hadn't called time and he hadn't picked the bails up. There were a few in the side that thought it was beyond the pale, but no one said it. Sobers told Greigy he should leave the ground in his car with him, otherwise he might not make it back to the hotel in one piece.

In Karachi, the students burned down the pavilion while we were still inside. The match and tour were called off.

"I I never got out as nightwatchman for England, and I'm quite proud about that" © Getty Images

"I I never got out as nightwatchman for England, and I'm quite proud about that" © Getty ImagesTom Graveney playing a T20 game would be like entering a Rolls-Royce in a stock car race.

I got 1607 wickets and John Emburey got 1608, both at 26 apiece, but he bowled 2000 more overs to get that wicket. His home ground was Lord's, which, in those days, was an infinitely better place to bowl spinners than The Oval. He was a fine bowler, but he was defensive and I was attacking, and on some wickets I felt I had the edge over him.

One year, Boycott had got 1300 runs in nine innings. We were playing Yorkshire at Bradford, and I had Graham Roope on Boycott's shoelaces on the off side, right on top of him. I ran up, bowled him off stump. As he walked past Roopey, he said, "I can't play that bowling, me." Roopey told me that, and I said, "Roopey, that ball did absolutely nothing. It didn't drift, didn't turn, he just played inside the line."

As soon as I'd played representative cricket for England Schools - I used to bat No. 5 - I thought I might have a chance.

Kenny [Barrington] was a selfish player, but anyone who played like he did was always going to be more consistent than someone like Ted Dexter. He used to restrict himself to three shots, and that's why he didn't get out, whereas Ted played every shot in the book. Kenny's going to be more consistent, but Dexter will win you more games.

Closey [Brian Close] got one run in 59 minutes [at Old Trafford in 1976] and had the shit knocked out of him. He was in a terrible state when he came in. I got in as nightwatchman in the second innings and I didn't get out that night. Next morning, I'm walking out with John Edrich and he asked me, "Which end do you fancy?" I told him I'd have Andy Roberts' end as he was a bit of light relief. John pisses himself laughing: "I tell you now, if Andy Roberts is light relief then we've got problems."

-----Further inputs from Pat Pocock when asked what he meant by the use of the wrist in spin bowling:

Firstly, my comment was in relation to left and right arm finger spinning, not wrist spinners as that is an entirely different technique.

When Monty Panasar was current, every pundit & journalist said “Monty has to bowl with more variation” – it was totally obvious. If we say for example that the majority of spinners vary their pace from, say 50 – 64 mph, this is not done with merely lobbing the balls up on the slower deliveries. A great exponent of what I was saying was Bishen Bedi. Bish could vary his pace with almost the same arm speed every ball. He did this by sometimes holding his wrist back and other times for pushing his wrist in hard behind the ball. Change of speed without any deception has little effect – it’s when a bowler makes the player arrive at his shot too early, or makes then jab the ball out when it’s a quicker ball, is what variation is all about. This is very important when trying to make the batsmen mis-read the length of the ball.

Bowlers need to get the basics of their action first, most importantly the smoothest rhythm they can manage – then, this gives them the ability to bowl the same ball time and time again, sometimes under pressure, and maintain control. Once they have learnt this………then they can experiment with their wrist…… in the nets?

Spin bowling is almost a forgotten art mainly because players and coaches have so much less experience in playing and teaching it!! When we don’t produce spin bowlers in County cricket the batsmen also suffer from opportunities to learn a technique against spin bowling. Some of our England batsmen in India will be on a vertical learning curve this winter I fear!!

-----

Bowlers need to get the basics of their action first, most importantly the smoothest rhythm they can manage – then, this gives them the ability to bowl the same ball time and time again, sometimes under pressure, and maintain control. Once they have learnt this………then they can experiment with their wrist…… in the nets?

Spin bowling is almost a forgotten art mainly because players and coaches have so much less experience in playing and teaching it!! When we don’t produce spin bowlers in County cricket the batsmen also suffer from opportunities to learn a technique against spin bowling. Some of our England batsmen in India will be on a vertical learning curve this winter I fear!!

-----