'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label tiger. Show all posts

Showing posts with label tiger. Show all posts

Friday, 29 August 2025

Wednesday, 31 May 2023

Thursday, 13 June 2019

Higher Education in The USA: Rigged from inside and outside?

Edward Luce in The FT

“Nothing is fun until you are good at it,” said Amy Chua in her book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. Eight years later the Yale professor continues to display her prowess.

This week Sophia Chua-Rubenfeld, Ms Chua’s daughter, was hired as a Supreme Court clerk by Brett Kavanaugh — the judge for whom her mother vouched during his stormy Senate hearings last autumn.

Ms Chua is a shrewd string-puller. A Supreme Court clerkship sets up a young lawyer for life. Whether she is enjoying the publicity is another matter. Overnight the Chuas have turned into emblems of what Americans distrust about their meritocracy.

There is much more where that came from. What Ms Chua did was brazen. The liberal academic offered a very public endorsement of the conservative Mr Kavanaugh. As the head of the Yale committee that steers graduates into highly-coveted clerkships, Ms Chua boosted his credibility with her endorsement.

But the apparent quid pro quo was legal. Actresses Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman, on the other hand, are accused of having broken the law.

The first is alleged to have paid $500,000 to fake athletics records that would help her two daughters enter the University of Southern California. The second has pleaded guilty to paying $15,000 to cheat on her daughter’s standardised admission test. Both Hollywood actresses, and one of their husbands, face likely jail in the “Operation Varsity Blues” scandal.

Americans would be forgiven for blurring the moral of these tales.

On pure arithmetic, the average American’s chances of entering a top university are tiny if they are born into the wrong home. Studies show that an eighth grade (14-year-old) child from a lower income bracket who achieves maths results in the top quarter is less likely to graduate than a kid in the upper income bracket scored in the bottom quarter. This is the reverse of how meritocracy should work. Children from the wealthiest 1 per cent take more Ivy League places than the bottom 60 per cent combined. Being born under a roof like Ms Chua’s — with two high-achieving parents obsessed with your success — is almost impossible to match.

That is how most of the world works. The US has erected three additional barriers. The first is legacy places. In contrast to most other democracies, America’s top universities credit an applicant if a parent, or grandparent, went to the school. A better name for this would be “hereditary preference”, which is antithetical to America’s creed. Roughly one in six Ivy League places are taken by children of alumni. This sharply reduces the places available to children of talent from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The second is affirmative action. The courts will soon rule on an Asian-American class action suit alleging that Harvard University discriminated against them. A significant — though artfully selected — share of places are reserved for children of Hispanic and African-American backgrounds. The fact that some of those are also legacy applicants adds a layer of irony. Whichever way it goes, the case is likely to end up in the Supreme Court. Mr Kavanaugh, who is a legacy graduate of Yale, could prove the decisive vote on whether affirmative action will survive. That prospect, too, is rich in irony.

The third barrier is brute wealth. If you endow a library, or a medical lab, the university will bend over backwards to admit your child. A prime example is Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in-law, whose poor SAT scores critics perceive may have been outweighed by his father’s $2.5m donation to Harvard. The US tax system even rewards such palm-greasing by making it tax-deductible. The fact that the best universities are richer than some countries (Harvard’s $38bn endowment is larger than the GDPs of El Salvador and Nicaragua combined) is no check on their ambitions. They always want more.

The most egregious figure in the college admissions scandal is William McGlashan, a former partner at TPG, the private equity firm. He allegedly offered a bribe of $250,000 to get his son into a top university. His job was to head TPG’s social impact unit — capitalism’s virtue signalling arm.

You do well by doing good, goes the saying. Which brings us back to Ms Chua. The best restraint on any elite is its sense of shame. Without that code, anything is possible. Everyone in America seems to know the system is rigged. The real distinction is whether you rig things from inside the law or outside.

“Nothing is fun until you are good at it,” said Amy Chua in her book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. Eight years later the Yale professor continues to display her prowess.

This week Sophia Chua-Rubenfeld, Ms Chua’s daughter, was hired as a Supreme Court clerk by Brett Kavanaugh — the judge for whom her mother vouched during his stormy Senate hearings last autumn.

Ms Chua is a shrewd string-puller. A Supreme Court clerkship sets up a young lawyer for life. Whether she is enjoying the publicity is another matter. Overnight the Chuas have turned into emblems of what Americans distrust about their meritocracy.

There is much more where that came from. What Ms Chua did was brazen. The liberal academic offered a very public endorsement of the conservative Mr Kavanaugh. As the head of the Yale committee that steers graduates into highly-coveted clerkships, Ms Chua boosted his credibility with her endorsement.

But the apparent quid pro quo was legal. Actresses Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman, on the other hand, are accused of having broken the law.

The first is alleged to have paid $500,000 to fake athletics records that would help her two daughters enter the University of Southern California. The second has pleaded guilty to paying $15,000 to cheat on her daughter’s standardised admission test. Both Hollywood actresses, and one of their husbands, face likely jail in the “Operation Varsity Blues” scandal.

Americans would be forgiven for blurring the moral of these tales.

On pure arithmetic, the average American’s chances of entering a top university are tiny if they are born into the wrong home. Studies show that an eighth grade (14-year-old) child from a lower income bracket who achieves maths results in the top quarter is less likely to graduate than a kid in the upper income bracket scored in the bottom quarter. This is the reverse of how meritocracy should work. Children from the wealthiest 1 per cent take more Ivy League places than the bottom 60 per cent combined. Being born under a roof like Ms Chua’s — with two high-achieving parents obsessed with your success — is almost impossible to match.

That is how most of the world works. The US has erected three additional barriers. The first is legacy places. In contrast to most other democracies, America’s top universities credit an applicant if a parent, or grandparent, went to the school. A better name for this would be “hereditary preference”, which is antithetical to America’s creed. Roughly one in six Ivy League places are taken by children of alumni. This sharply reduces the places available to children of talent from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The second is affirmative action. The courts will soon rule on an Asian-American class action suit alleging that Harvard University discriminated against them. A significant — though artfully selected — share of places are reserved for children of Hispanic and African-American backgrounds. The fact that some of those are also legacy applicants adds a layer of irony. Whichever way it goes, the case is likely to end up in the Supreme Court. Mr Kavanaugh, who is a legacy graduate of Yale, could prove the decisive vote on whether affirmative action will survive. That prospect, too, is rich in irony.

The third barrier is brute wealth. If you endow a library, or a medical lab, the university will bend over backwards to admit your child. A prime example is Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in-law, whose poor SAT scores critics perceive may have been outweighed by his father’s $2.5m donation to Harvard. The US tax system even rewards such palm-greasing by making it tax-deductible. The fact that the best universities are richer than some countries (Harvard’s $38bn endowment is larger than the GDPs of El Salvador and Nicaragua combined) is no check on their ambitions. They always want more.

The most egregious figure in the college admissions scandal is William McGlashan, a former partner at TPG, the private equity firm. He allegedly offered a bribe of $250,000 to get his son into a top university. His job was to head TPG’s social impact unit — capitalism’s virtue signalling arm.

You do well by doing good, goes the saying. Which brings us back to Ms Chua. The best restraint on any elite is its sense of shame. Without that code, anything is possible. Everyone in America seems to know the system is rigged. The real distinction is whether you rig things from inside the law or outside.

Wednesday, 8 May 2013

Cricket - Mallett on Grimmett and O'Reilly

The Tiger and the Fox

Bill O'Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett were the greatest spin-bowling partnership of their age, and arguably the best in Test history

Ashley Mallett

May 8, 2013

A

| |||

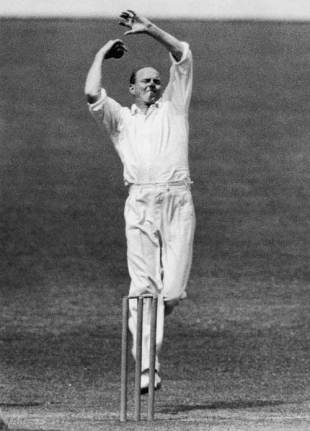

Between the world wars, Bill O'Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett reigned supreme. They were the greatest spin-bowling partnership of their age, and arguably the best in Test history. O'Reilly, the Tiger, and Grimmett, the Fox, were both legspinners but they approached their art as differently as Victor Trumper and Don Bradman approached batting.

Arms and legs flailing in the breeze, O'Reilly stormed up to the crease with steam coming out of his ears. He believed in all-out aggression, and called himself a "boots'n'all" competitor. Bradman, who reckoned O'Reilly to have been the best bowler he saw or played against, said he had the ability to bowl a legbreak of near medium pace that consistently pitched around leg stump and turned to nick the outside edge or the top of off.

"Bill also bowled a magnificent bosey which was hard to pick, and which he aimed at middle and leg stumps," said Bradman in a letter he wrote to me in 1989. "It was fractionally slower than his legbreak and usually dropped a little in flight and 'sat up' to entice a catch to one of his two short-leg fieldsmen. These two deliveries, combined with great accuracy and unrelenting hostility, were enough to test the greatest of batsmen, particularly as his legbreak was bowled at medium pace - quicker than the normal run of slow bowlers - making it extremely difficult for a batsman to use his feet as a counter measure. Bill will always remain, in my book, the greatest of all."

O'Reilly first came up against Bradman in the summer of the 1925-26 season, when Tiger's Wingello took on the might of Bradman's Bowral. Sixteen-year-old Bradman, who to his 19-year-old adversary was hardly any bigger than the outsized pads he wore, edged a high-bouncing legbreak straight to first slip when on 32. But the Wingello captain, Gallipoli hero Selby Jeffrey, was busy lighting his pipe, and the chance went begging.

Stumps were drawn with Bradman 232 not out, leaving the Tiger snarling in disbelief and raising his eyes to the heavens at the blatant injustice of it all. The game resumed the next Saturday afternoon. Bradman faced the first ball from the wounded Tiger. It pitched leg and took the top of off.

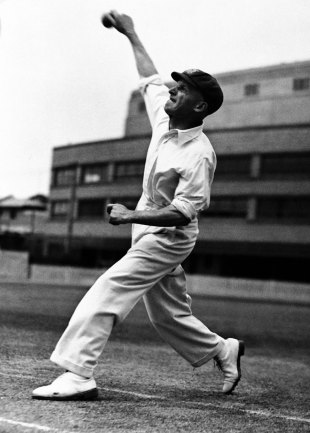

In the year O'Reilly came into this world, 1905, Grimmett tore a hole in his new blue suit, clambering over the barbed wire at Wellington's Basin Reserve to watch Trumper hit a famous hundred. In 1914, Grimmett sailed into Sydney from his native New Zealand, seeking cricketing fame. But it wasn't until a long stint in Sydney and more fruitless years in Melbourne before a last throw of the dice in Adelaide proved to be a haven for an unwanted bowler.

Grimmett began his Test career against England at the SCG in 1925, taking a match haul of 11 for 82. He starred in Australian tours of England in 1926 and 1930, but it was in the Adelaide Test of 1932, O'Reilly's debut, that the Tiger and the Fox first joined forces. Grimmett was the master and O'Reilly the apprentice, in a game that was a triumph for Bradman (299 not out) and Grimmett (14 for 199).

| It is virtually impossible to compare spinners from different eras, although most would agree the best three legspinners in Test cricket were Grimmett, O'Reilly, and Warne | |||

O'Reilly was amazed by the way Grimmett bowled: "I learned a great deal watching Grum [the nickname Bill always used for his spinning mate] wheel away. I watched him like a hawk. He was completely in control. His subtle change of pace impressed me greatly."

The pair played two Tests that series and two more in the Bodyline series of 1932-33, before O'Reilly took over as Australia's leading spinner when Grimmett was dropped. They were back in harness for the 1934 Ashes - the Tiger's first England tour, Grimmett's third. Here's O'Reilly on their unforgettable partnership:

"It was on that tour that we had all the verbal bouquets in the cricket world thrown at us as one of the greatest spin combinations Test cricket had seen. Bowling tightly and keeping the batsmen unremittingly on the defensive, we collected 53 [Grimmett 25, O'Reilly 28] of the 73 English wickets that fell that summer. Each of us collected more than 100 wickets on tour and it would have needed a brave, or demented, Australian at that time to suggest that Grimmett's career was almost ended."With Grum at the other end I knew full well that no batsman would be allowed the slightest respite. We were fortunate in that our styles supplemented each other. Grum loved to bowl into the wind, which gave him an opportunity to use wind-resistance as an important adjunct to his schemes regarding direction. He had no illusions about the ball 'dropping', as we hear so often these days, before its arrival at the batsman's proposed point of contact. To him that was balderdash. In fact, he always loved to hear people making up verbal explanations for the suspected trickery that had brought a batsman's downfall. If a batsman had thought the ball had dropped, all well and good. Grimmett himself knew that it was simply change of pace that had made the batsman think that such an impossibility had happened."

| |||

While O'Reilly was all-out aggression, Grimmett was steady and patient. They both possessed a stock ball that turned from leg. O'Reilly's deliveries came at pace: his legbreak spat like a striking cobra, and his wrong'un reared at the chest of the batsman. For any batsman in combat with the Tiger there was no respite, no place to hide.

In contrast, Grimmett wheeled away in silence. He was like the wicked spider, spinning a web of doom. Sometimes it took longer for him to snare his victim, but despite their vastly different styles and methods of attack they were both deadly. A batsman caught at cover off Grimmett was just as out as a man who lost his off stump to a ball that pitched leg and hit the top of off from O'Reilly.

Bradman once wrote me: "I always classified Clarrie Grimmett as the best of the genuine slow legspinners, (I exclude Bill O'Reilly because, as you say, he was not really a slow leggie) and what made him the best, in my opinion, was his accuracy. Arthur Mailey spun the ball more - so did Fleetwood-Smith and both of them bowled a better wrong'un but they also bowled many loose balls. I think Mailey's bosey was the hardest of all to pick.

"Clarrie's wrong'un was in fact easy to see. He telegraphed it and he bowled very few of them. His stock-in-trade was the legspinner with just enough turn on it, plus a really good topspin delivery and a good flipper (which he cultivated late in life). I saw Clarrie in one match take the ball after some light rain when the ball was greasy and hard to hold, yet he reeled off five maidens without a loose ball. His control was remarkable."

Grimmett invented the flipper, which Shane Warne, at the height of his brilliant career, bowled so well. Like Grimmett, Warne didn't have a great wrong'un, but he possessed a terrific stock legbreak and a stunning topspinner. When O'Reilly asked SF Barnes where he placed his short leg for the wrong'un, Barnes replied: "Never bowled the bosey… didn't need one."

Imagine if Grimmett and O'Reilly had played 145 Tests, the same number as Warne. At the rate they took their wickets, Grimmett would have snared a shade under 870 and O'Reilly 770. In reality Grimmett played just 37 Tests and O'Reilly 27, but what an impact they had on cricket. It is virtually impossible to compare spinners from different eras, although most would agree the best three legspinners in Test cricket were Grimmett, O'Reilly, and Warne.

The Tiger and the Fox were unique in their contrasting styles, but they had one thing in common: they were spin-bowling predators. Their prey was any batsman who ventured to the crease when they were on the hunt.

Sunday, 26 August 2012

The Tourist Isn’t An Endangered Animal

DHRITIMAN MUKHERJEE

Exclusion of budget tourists can hit support for conservation

Tourism can increase its natural capital by converting farms to wildlife viewing land, with shared profits

K. ULLAS KARANTH in Outlook india

The media splash—exemplified by a hyper-ventilating Guardian report following the Supreme Court’s July 2012 interim order suspending tourism in some tiger reserves—has convinced the public that all wildlife tourism activity in India stands permanently abolished. Following the August 22 ruling on a review petition by the SC, in which it extended its ban on tourism in the ‘core areas’ of tiger reserves, people might think such a shutdown portends a disastrous collapse of public support to tiger conservation. These are exaggerations arising out of a flawed reading.

Wildlife tourism has been temporarily halted only in tiger reserves, that too only in states that have not notified ‘buffer zones’ mandated by law. Tourism is going on unhindered at all other wildlife reserves, including tiger reserves where buffer zones have been notified. The intent of the court’s order appears to be to compel remaining states to create buffers around already notified core areas or ‘critical tiger habitats’, with the suspension of tourism as a threat. The issue, as it has been framed by the court, will hopefully renew focus on the flawed boundaries of some of these critical tiger habitats, for both scientific and practical reasons.

Broadly, there are two kinds of wildlife tourism being practised in the country. The first is ‘budget tourism’, affordable to the non-affluent. My career as a naturalist was nurtured decades ago as one such tourist who paid 16 rupees for a van ride to watch wildlife rebound from the brink in Nagarahole, Karnataka. Budget wildlife tourism emerged in 1970s, when wildlife began to recover after a pioneer generation of foresters implemented Indira Gandhi’s tough new laws.

The high-end version of tiger tourism, kicking up so much dust now, came later when wildlife got habituated to tourists and could be easily watched. It typically features luxury accommodation and fine food (often with swimming pools, saunas, therapeutic massage thrown in). The ‘boutique tourism’ we see at reserves like Bandhavgarh, Kanha and Ranthambhore can be enjoyed only by the well-off.

The rise of boutique tourism is a consequence of India’s economic growth, which generated large disposable incomes that could be tapped. Its concern is profit, not conservation education. This is not a crime, as some appear to believe—but nor is it a great virtue. Although high-end tourism generates some local jobs and benefits, unlike in Africa these are not at all significant when scaled to the size of local economies, let alone state or national ones. Wildlife reserves cannot be India’s ‘engines of economic growth’. Their primary value is for educating the public about our threatened wildlife, generating support and enabling conservation action.

High-end tourism necessarily targets spectacular animals like tigers, lions, rhinos and elephants that attract top dollars. It has spread rapidly across the country, with even the public sector joining in. As a result, in most good wildlife reserves, the prices charged for entry, vehicle rides and accommodation have all skyrocketed beyond the reach of average citizens. However, because the size of these reserves or their carrying capacity has not expanded, richer tourists are steadily squeezing out budget tourists.

This sad consequence of spreading high-end tourism has gone unnoticed in the present debate. Exclusion of the budget tourists is far more likely to undermine long-term public support for wildlife conservation in India than the court’s suspension of tourism in a few high-profile tiger reserves. To ignore this reality and to portray all wildlife tourism as one homogeneous, benevolent entity is highly misleading.

The arguments that the tourism industry’s watchful eyes are necessary to protect wildlife and its ‘ban’ will lead to collapse of wildlife protection are also facetious. The high-end tourism boom, in fact, followed years after wildlife populations had rebounded: to claim that it recovered wildlife is to mistake the effect for the cause. What is particularly muddying this logical stream in the present debate is the fact that a handful of genuine conservationists are loudly pleading the industry’s case. However, in my view, they do not represent a reasonable sample of general industry behaviour or practices by any stretch of imagination.

Wildlife tourism has been temporarily halted only in tiger reserves, that too only in states that have not notified ‘buffer zones’ mandated by law. Tourism is going on unhindered at all other wildlife reserves, including tiger reserves where buffer zones have been notified. The intent of the court’s order appears to be to compel remaining states to create buffers around already notified core areas or ‘critical tiger habitats’, with the suspension of tourism as a threat. The issue, as it has been framed by the court, will hopefully renew focus on the flawed boundaries of some of these critical tiger habitats, for both scientific and practical reasons.

Broadly, there are two kinds of wildlife tourism being practised in the country. The first is ‘budget tourism’, affordable to the non-affluent. My career as a naturalist was nurtured decades ago as one such tourist who paid 16 rupees for a van ride to watch wildlife rebound from the brink in Nagarahole, Karnataka. Budget wildlife tourism emerged in 1970s, when wildlife began to recover after a pioneer generation of foresters implemented Indira Gandhi’s tough new laws.

The high-end version of tiger tourism, kicking up so much dust now, came later when wildlife got habituated to tourists and could be easily watched. It typically features luxury accommodation and fine food (often with swimming pools, saunas, therapeutic massage thrown in). The ‘boutique tourism’ we see at reserves like Bandhavgarh, Kanha and Ranthambhore can be enjoyed only by the well-off.

The rise of boutique tourism is a consequence of India’s economic growth, which generated large disposable incomes that could be tapped. Its concern is profit, not conservation education. This is not a crime, as some appear to believe—but nor is it a great virtue. Although high-end tourism generates some local jobs and benefits, unlike in Africa these are not at all significant when scaled to the size of local economies, let alone state or national ones. Wildlife reserves cannot be India’s ‘engines of economic growth’. Their primary value is for educating the public about our threatened wildlife, generating support and enabling conservation action.

High-end tourism necessarily targets spectacular animals like tigers, lions, rhinos and elephants that attract top dollars. It has spread rapidly across the country, with even the public sector joining in. As a result, in most good wildlife reserves, the prices charged for entry, vehicle rides and accommodation have all skyrocketed beyond the reach of average citizens. However, because the size of these reserves or their carrying capacity has not expanded, richer tourists are steadily squeezing out budget tourists.

This sad consequence of spreading high-end tourism has gone unnoticed in the present debate. Exclusion of the budget tourists is far more likely to undermine long-term public support for wildlife conservation in India than the court’s suspension of tourism in a few high-profile tiger reserves. To ignore this reality and to portray all wildlife tourism as one homogeneous, benevolent entity is highly misleading.

|

On the other hand, it would also be wrong to portray ‘tiger tourism’ as the most important threat to wild tigers. It is not. Direct killing by criminal gangs, poaching of prey animals, livestock grazing, the collection of forest produce by locals, development of infrastructure such as mines and dams in ecologically sensitive areas, as well as the misapplication of the Forest Rights Act, pose much bigger threats. Ill-conceived and over-funded ‘habitat improvement’ practised by reserve managers is also emerging as a potent threat.

However, it cannot also be denied that increasing tourism pressure, ‘more of vehicles, riding elephants, fuel-wood consumption and water diversion, as well as broader scale habitat fragmentation’ are of increasing concern. This is particularly true because much of the high-end tourism pressure is targeted at a few major reserves that cover less than 1/1000th of our land.

Clearly, the present model of wildlife tourism is unsustainable in a country with over a billion people with an annual economic growth rate of 6-8 per cent. Drastic regulation is urgently needed and more sustainable tourism models must be built. Preferably, these should emerge from shared conservation concerns rather than mere government diktat or court orders. I urge that the promotion of the economic self-interest of farmers living in close proximity to wildlife should also be a key component of any new model of wildlife tourism.

If the economic force manifested as boutique wildlife tourism is to genuinely serve conservation, it must urgently reinvent itself. How can it do so?

Essentially the land-base for wildlife viewing must expand outward from our tiny nature reserves, creating additional wildlife habitat as economic growth and demand increase. Pragmatically, the only possibility for such expansion has to rely on private lands stretching outwards from our wildlife reserves in all directions. Therefore, instead of deploying its political clout to seek more concessions inside existing wildlife reserves, or even pleading for allotment of publicly owned lands outside, the high-end tourism industry would be wiser in partnering commercially with farmers around major reserves that shelter tigers, lions, rhinos or elephants that its clients will pay to watch.

Only by converting farms to land for wildlife viewing, by means of reasonable profit-sharing mechanisms, can this industry hope to increase its true ‘natural capital’—wildlife and wild lands. Unfortunately, the loss of this natural capital is now not even a part of the industry’s business models. Furthermore, such profit-sharing will undoubtedly lessen the hostility that locals feel towards wildlife reserves as playgrounds reserved for the rich. It will also reduce the industry’s crippling dependence on fickle government policies or unpredictable litigation for its very survival.

The success of the ‘wildlife habitat expansion model’ I propose will depend on the underlying economics being robust. It will not depend merely on pious conservation concerns but on pursuit of economic self-interest by both industry and farmers. It may not meet the gold standards of North Korean socialism, but I believe it can offer a pragmatic long-term solution framed within the overall model of development followed by every elected government for the past two decades.

What then of the ordinary budget tourists? It’s imperative that publicly owned wildlife reserves be accessible to them at reasonable costs, even as commercial tourism expands outwards in ever widening circles. What I have proposed is indeed closer to the South African model of wildlife tourism, which industry advocates now demand in India. That model includes well-run, properly zoned national parks like Kruger that benefit large numbers of less-affluent tourists. These are surrounded and buffered by an expanding network of private reserves catering to visitors with deeper pockets. In the process hundreds of square kilometres of marginal farmland, cattle ranches and Biltong (game meat) ranches have turned into additional well-managed wildlife tourism reserves. This case comes as a warning bell for India’s wildlife tourism industry: if it does not confront the economic issue of its own dwindling natural capital, soon it will have no place to go.

(Karanth is director for Science-Asia, Wildlife Conservation Society)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)

.png)

.png)