I'm an atheist but … I won't try to deconvert anyone

New atheism won't tolerate the freedom to believe in God. But life's far more interesting if we admit we might be wrong, right?

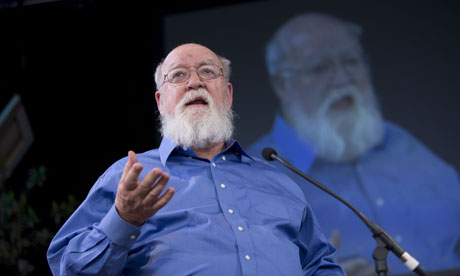

Philosopher and 'new atheist' Daniel Dennett speaking at the Hay Festival. Photograph: David Levenson/Getty Images

Last week I interviewed the philosopher Daniel Dennett about new atheism, (the interview will be up on this site soon). I haven't got the tape myself, so I can't swear to the verbatim accuracy of the quotes I remember, but at one stage I said something to the effect that new atheism seems to me to reproduce all the habits that made religion obnoxious, like heresy hunting. He asked what I meant, and I gave the example of "atheists but", a species of which he is particularly disdainful. They are the people who will say to him and his fellow zealots "I am an atheist, but I don't go along with your campaign." I'm one of them.

He accused me of a kind of intellectual snobbery – of believing that I am clever and brave and strong enough to understand that there is no God, but that this is a discovery too shattering for the common people who should be left in the comfort of their ignorance.

This was indeed the classic position of the anti-religious philosophers of the enlightenment. It is what Voltaire believed, and Gibbon, and Hume. So it's not as if you have to be an idiot to think that atheism is medicine too strong for most people. And when you see the relish with which some atheists dismiss their opponents as "morons" you might even suppose that even some atheists are attracted by the idea that they are of necessity cleverer than believers.

But that's not in fact my position at all. The reason that I don't go around trying to deconvert all my Christian friends is that they know the arguments against a belief in God so very much better than I do. I can entertain the possibility that Christianity is true. They have to take it seriously. I don't believe I ought to love my neighbour, however much patience and humility this takes. I know that prayers go unanswered: they know their own prayers do.

I am not the person who has to bury the tramps, to comfort the parents whose children have died, or to read the Bible in the hope that it will yield meaning. I don't even have to believe that the Holy Spirit works through the college of cardinals or General Synod, so that their deliberations are in some way connected with the redemption of the world.

Only the last of those duties is a mark of moral or intellectual weakness. In fact, since I like my friends to be admirable, which often means cleverer and nicer than I am, my Christian friends don't seem to me stupid or cowardly. I know lots of Christians who are both, of course. But that's true of atheists and Muslims as well.

There is a general point here about the inadequacy of all theological opinions. The "but" in "atheists but" is a mark of humility, to be worn with pride. To be right on intellectual matters is of limited importance and interest to the outside world. Assuming – rashly – that you are an intellectual, it is very much easier to be right about ideas than to work out their implications and act on them in real life. But that's the bit that matters more, if only because failure to act on your own beliefs involves lying to yourself, and this will over time corrupt the capacity for thought.

The "but" is a way of saying that the times when we are right are mostly less interesting than the times when we are wrong. They certainly demand our attention less. It's a way of saying that we might be wrong, and actually meaning it. It's a demand to try to listen to what the other person means, rather than dismiss what they say just because it makes no sense.

It is, in short, a rejection of all the values of online argument so it really can't be wrong. Discuss.

No comments:

Post a Comment