'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label worship. Show all posts

Showing posts with label worship. Show all posts

Thursday, 19 May 2022

Monday, 22 October 2018

The pilgrimage’s progress

Janaki Nair in The Hindu

Shortcuts and compromises

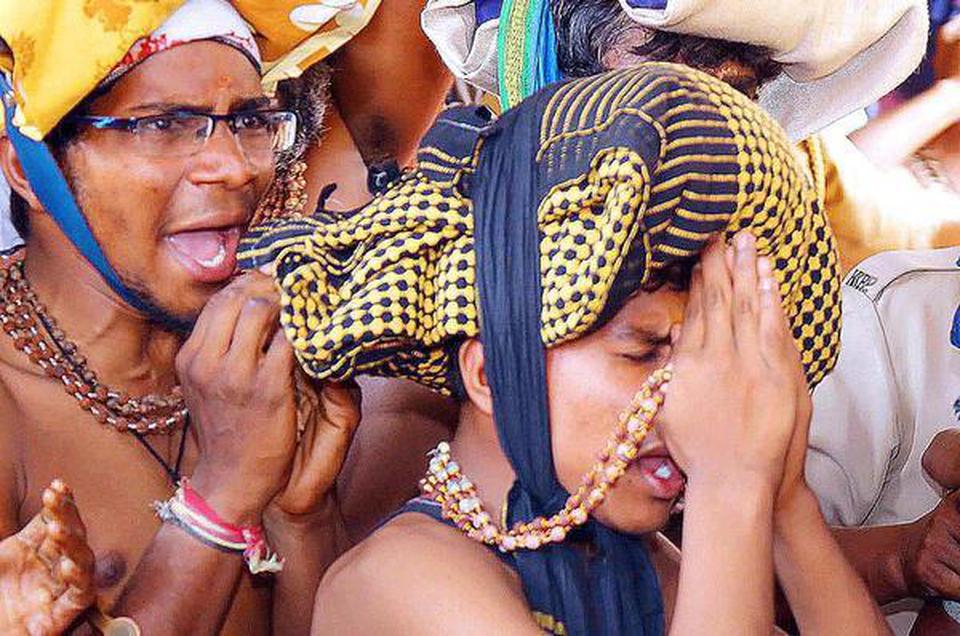

In the 1960s, the young ‘Ayyappa’ would have been among the 15,000 or so who made that arduous journey. No longer. In the past five decades, as the numbers have burgeoned to millions, Lord Ayyappa has been witness to, and extremely tolerant of, every aspect of the pilgrimage being changed beyond recognition. Let us begin with the most important reason being cited for prohibiting women pilgrims of menstruating age: that they cannot maintain the 41-day vratham. Yet, as we know from personal knowledge, and from detailed anthropological studies of this pilgrimage, the shortcuts and compromises on that earlier observance have been many and Lord Ayyappa himself seems to have taken the changes in his stride.

Not all those who reach the foot of the 18 steps that have to be mounted for the darshan of the celibate god observe all aspects of the vratham. A corporate employee, such as one in my family, may observe the restrictions on meat, alcohol and sex, but has given up the compulsion of wearing black or being barefoot. I recall being startled when I saw ‘Ayyappas’ clad in black enjoying a smoke in the corner of the newspaper office where I once worked; I was told that it was only alcohol that was to be abjured. My surprise was greater when I saw several relatives donning the mala about a week before setting off on the pilgrimage, a serious abbreviation of the 41-day temporary asceticism. Though this has meant no diminution in the faith of those visiting the shrine, clearly the pilgrim’s progress has been adapted to the temporalities of modern life.

Lord Ayyappa has surely observed that the longer pedestrian route to his forest shrine has been shortened by the bus route. From 1,29,000 private vehicles in 2000 to 2,65,000 in 2005, not to mention the countless bus trips, this has resulted in intolerable strains on a fragile ecology. In other words, pilgrim tourism, far from being promoted by women’s entry to Sabarimala, had already reached unbearable limits.

One of the most vital practices of this pilgrimage enjoins the pilgrim to carry his own consumption basket: nothing should be available for purchase. Provisions for drinking and cleaning water apart, the sacred geography of the shrine was preserved by such restrictions on consumption. But like many large religious corporations such as Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, the conveniences of commerce have pervaded every step of the way, with shops selling ‘Ayyapan Bags’ and other ‘ladies’ items’ that can be carried back to the women in the family. In addition to the gilding of the 18 steps, which naturally disallows the quintessential ritual of breaking coconuts, Lord Ayyappa may perhaps have been somewhat amused by the conveyor belt that carries the offerings to be counted. Those devotees who take a ‘return route’ home via Kovalam to relieve the severities of the temporary celibacy would perhaps be pardoned, even by the Lord, as much as by anthropologists who have noted such interesting accretions. And in 2016, according to the Quarterly Current Affairs, the Modi government announced plans to make Sabarimala an International Pilgrim Centre (as opposed to the State government’s request to make it a National Pilgrim Centre) for which funds “would never be a problem”.

The invention of ‘tradition’

Lest this be mistaken for a cynical recounting of the countless ways in which the pilgrimage has been ‘corrupted’, let me hasten to say that my point is far simpler. Anyone who studies the social life and history of religion will recognise that practices are constantly adapted and reshaped, as collectivities themselves are changed, adapted and refashioned to suit the constraints of cash, time or even aesthetics. For this, the historians E.J. Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger coined the term “the invention of tradition”. Who amongst us does not, albeit with a twinge of guilt, agree to the ‘token’ clipping of the hair at Tirupati in lieu of the full head shave? Who does not feel an unmatched pleasure in the piped water that gently washes the feet as we turn the corner into the main courtyard of Tirupati after hours of waiting in hot and dusty halls? And who does not feel frustrated at the not-so-gentle prod of the wooden stick by the guardian who does not allow you more than a few seconds before the deity at Guruvayur? All these belong properly to the invention of ‘tradition’ leaving no practice untouched by the conveniences of mass management.

But perhaps the most important invention of ‘tradition’ was the absolute prohibition of women of menstruating age from worship at Sabarimala under rules 3(b) framed under the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorisation of Entry) Act, 1965. Personal testimonies have shown that strict prohibition was not, in fact, always observed, but would such a legal specification have been necessary at all if everyone was abiding by that usage or custom from ‘time immemorial’? It is a “custom with some aberrations” as pointed out by Indira Jaisingh, citing the Devaswom Board’s earlier admission that women had freely entered the shrine before 1950 for the first rice feeding ceremonies of their children.

Elsewhere, the celibate Kumaraswami, in Sandur in Karnataka where women were strictly disallowed, has gracefully conceded space to women worshippers since 1996. “The heavens have not fallen,” Gandhi remarked in 1934 when “a small state in south India [Sandur] has opened the temple to the Harijans.” Lord Ayyappa, who has tolerated innumerable changes in the behaviour of his devotees, will surely not allow his wrath to manifest itself. He will be saddened by the hypermobilisation that surrounds the protests today, but would be far more forgiving than the men — and those women — who make, unmake and remake the rules of worship.

The rules of worship are made, unmade, and remade over time and Sabarimala is no exception

I remember seeing the ‘birth’ of Ayyappa on stage during a Kathakali performance. Following the drama of Bhasmasura’s destruction by Vishnu as Mohini, Shiva’s fear turning to gratitude, the two ‘male’ gods retreated behind the curtain drawn across the stage. The curtain trembled to the clash and roar of cymbals, drums and singing, before being lowered to reveal an image of Ayyappa. We were overawed by the performance and did not think of raising questions about the ways of the gods. I remember too, in the late 1960s, participating in the ‘kettanara’ rituals (the placing of the bundle of offerings and some items for sustenance on the pilgrim’s head before he sets off on the pilgrimage) of young cousins departing for Sabarimala on foot. The ritual involved all the women in the household. The young men were unshaven, in black, had donned the mala, and were ready to walk the long route barefoot after having observed their 41-day vrathams. I was overawed by the faith of the young ‘Ayyappa’, the women, and was too young to raise any ‘why nots’.

I remember seeing the ‘birth’ of Ayyappa on stage during a Kathakali performance. Following the drama of Bhasmasura’s destruction by Vishnu as Mohini, Shiva’s fear turning to gratitude, the two ‘male’ gods retreated behind the curtain drawn across the stage. The curtain trembled to the clash and roar of cymbals, drums and singing, before being lowered to reveal an image of Ayyappa. We were overawed by the performance and did not think of raising questions about the ways of the gods. I remember too, in the late 1960s, participating in the ‘kettanara’ rituals (the placing of the bundle of offerings and some items for sustenance on the pilgrim’s head before he sets off on the pilgrimage) of young cousins departing for Sabarimala on foot. The ritual involved all the women in the household. The young men were unshaven, in black, had donned the mala, and were ready to walk the long route barefoot after having observed their 41-day vrathams. I was overawed by the faith of the young ‘Ayyappa’, the women, and was too young to raise any ‘why nots’.

Shortcuts and compromises

In the 1960s, the young ‘Ayyappa’ would have been among the 15,000 or so who made that arduous journey. No longer. In the past five decades, as the numbers have burgeoned to millions, Lord Ayyappa has been witness to, and extremely tolerant of, every aspect of the pilgrimage being changed beyond recognition. Let us begin with the most important reason being cited for prohibiting women pilgrims of menstruating age: that they cannot maintain the 41-day vratham. Yet, as we know from personal knowledge, and from detailed anthropological studies of this pilgrimage, the shortcuts and compromises on that earlier observance have been many and Lord Ayyappa himself seems to have taken the changes in his stride.

Not all those who reach the foot of the 18 steps that have to be mounted for the darshan of the celibate god observe all aspects of the vratham. A corporate employee, such as one in my family, may observe the restrictions on meat, alcohol and sex, but has given up the compulsion of wearing black or being barefoot. I recall being startled when I saw ‘Ayyappas’ clad in black enjoying a smoke in the corner of the newspaper office where I once worked; I was told that it was only alcohol that was to be abjured. My surprise was greater when I saw several relatives donning the mala about a week before setting off on the pilgrimage, a serious abbreviation of the 41-day temporary asceticism. Though this has meant no diminution in the faith of those visiting the shrine, clearly the pilgrim’s progress has been adapted to the temporalities of modern life.

Lord Ayyappa has surely observed that the longer pedestrian route to his forest shrine has been shortened by the bus route. From 1,29,000 private vehicles in 2000 to 2,65,000 in 2005, not to mention the countless bus trips, this has resulted in intolerable strains on a fragile ecology. In other words, pilgrim tourism, far from being promoted by women’s entry to Sabarimala, had already reached unbearable limits.

One of the most vital practices of this pilgrimage enjoins the pilgrim to carry his own consumption basket: nothing should be available for purchase. Provisions for drinking and cleaning water apart, the sacred geography of the shrine was preserved by such restrictions on consumption. But like many large religious corporations such as Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, the conveniences of commerce have pervaded every step of the way, with shops selling ‘Ayyapan Bags’ and other ‘ladies’ items’ that can be carried back to the women in the family. In addition to the gilding of the 18 steps, which naturally disallows the quintessential ritual of breaking coconuts, Lord Ayyappa may perhaps have been somewhat amused by the conveyor belt that carries the offerings to be counted. Those devotees who take a ‘return route’ home via Kovalam to relieve the severities of the temporary celibacy would perhaps be pardoned, even by the Lord, as much as by anthropologists who have noted such interesting accretions. And in 2016, according to the Quarterly Current Affairs, the Modi government announced plans to make Sabarimala an International Pilgrim Centre (as opposed to the State government’s request to make it a National Pilgrim Centre) for which funds “would never be a problem”.

The invention of ‘tradition’

Lest this be mistaken for a cynical recounting of the countless ways in which the pilgrimage has been ‘corrupted’, let me hasten to say that my point is far simpler. Anyone who studies the social life and history of religion will recognise that practices are constantly adapted and reshaped, as collectivities themselves are changed, adapted and refashioned to suit the constraints of cash, time or even aesthetics. For this, the historians E.J. Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger coined the term “the invention of tradition”. Who amongst us does not, albeit with a twinge of guilt, agree to the ‘token’ clipping of the hair at Tirupati in lieu of the full head shave? Who does not feel an unmatched pleasure in the piped water that gently washes the feet as we turn the corner into the main courtyard of Tirupati after hours of waiting in hot and dusty halls? And who does not feel frustrated at the not-so-gentle prod of the wooden stick by the guardian who does not allow you more than a few seconds before the deity at Guruvayur? All these belong properly to the invention of ‘tradition’ leaving no practice untouched by the conveniences of mass management.

But perhaps the most important invention of ‘tradition’ was the absolute prohibition of women of menstruating age from worship at Sabarimala under rules 3(b) framed under the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorisation of Entry) Act, 1965. Personal testimonies have shown that strict prohibition was not, in fact, always observed, but would such a legal specification have been necessary at all if everyone was abiding by that usage or custom from ‘time immemorial’? It is a “custom with some aberrations” as pointed out by Indira Jaisingh, citing the Devaswom Board’s earlier admission that women had freely entered the shrine before 1950 for the first rice feeding ceremonies of their children.

Elsewhere, the celibate Kumaraswami, in Sandur in Karnataka where women were strictly disallowed, has gracefully conceded space to women worshippers since 1996. “The heavens have not fallen,” Gandhi remarked in 1934 when “a small state in south India [Sandur] has opened the temple to the Harijans.” Lord Ayyappa, who has tolerated innumerable changes in the behaviour of his devotees, will surely not allow his wrath to manifest itself. He will be saddened by the hypermobilisation that surrounds the protests today, but would be far more forgiving than the men — and those women — who make, unmake and remake the rules of worship.

Wednesday, 29 November 2017

Beware the Tory cult that’s steering Brexit

Simon Kuper in The FT

In South Africa in 1856, the spirits of three ancestors visited a 15-year-old Xhosa girl called Nongqawuse. According to her uncle, who spoke for her, the spirits wanted the Xhosa to destroy their crops and cattle. The tribe’s ancestors would then return and drive the white settlers into the ocean. New, beautiful cattle would appear. The sun would turn red. The Xhosa duly began killing cattle and burning crops. This type of self-destructive quest for riches and freedom is now known as a “cargo cult”. (The word “cargo” denotes the western goods the tribe hopes to obtain.)

In South Africa in 1856, the spirits of three ancestors visited a 15-year-old Xhosa girl called Nongqawuse. According to her uncle, who spoke for her, the spirits wanted the Xhosa to destroy their crops and cattle. The tribe’s ancestors would then return and drive the white settlers into the ocean. New, beautiful cattle would appear. The sun would turn red. The Xhosa duly began killing cattle and burning crops. This type of self-destructive quest for riches and freedom is now known as a “cargo cult”. (The word “cargo” denotes the western goods the tribe hopes to obtain.)

Brexit voters come in endless varieties. However, the particular sect now steering Brexit — the Europhobe wing of the Conservative party — is turning into a cargo cult.

At the heart of it is ancestor worship. There’s a widespread belief in Britain that “the past is the real us”, says Catherine Fieschi, head of the Counterpoint think-tank. Perhaps no other country has as happy a relationship with its chequered history. And the self-appointed guardian of this relationship is the Conservative party.

Hardly any of today’s Tories actually remember Britain’s golden age of ruling India and winning the second world war. Even the party’s ageing members are merely the children of the Dunkirk generation. Economically, they have been the luckiest cohort in British history. But they and many other Tory MPs feel the shame of late birth. They disdain the UK’s tame, vegetarian, low-stakes, Brussels-based, post-imperial incarnation, which in 70 years offered nothing more glorious than the Falklands war. Now they have their own heroic project: Brexit.

Cargo cults typically start when the tribe feels it is in decline, surpassed by foreigners. In Melanesia, the Pacific region with a tradition of cargo cults, locals came to feel like “rubbish men” (the phrase is pidgin English) in comparison with rich Europeans. “A recurring feature of these cults is a belief that Europeans in some past age tricked Melanesians and are withholding from them their rightful share of material goods,” writes Paul Sillitoe, an anthropologist at Durham University.

To get these goods, the tribe has to mimic modern rituals that seem to have made advanced societies rich. Melanesians built airfields to receive the ancestors’ cargo. The Brexiter flies around signing trade deals. Meanwhile, the inferior goods of today’s “rubbish men” must be destroyed. Hence the eagerness in this Tory sect (but not among the British population at large) to shut off trade with Europe. If the correct rituals are followed, the ancestors will return. The sect leader, Boris Johnson, in his biography of Winston Churchill, sometimes seems to cast himself as the reincarnation of the great “glory-chasing, goalmouth-hanging opportunist”.

But the cargo cult is threatened by non-believers. They can ruin things by angering the ancestors. For 15 months, Nongqawuse blamed the failure of her prophecy on the few Xhosa — amagogotya, or “stingy ones” — who refused to kill their cattle.

Now, leading Conservatives are hunting British amagogotya. Chris Heaton-Harris seeks to out Remainer university teachers, Jacob Rees-Mogg castigates the BBC and the Bank of England’s governor Mark Carney as “enemies of Brexit”, while John Redwood urges the Treasury “to have more realistic, optimistic forecasts”. The sect also suspects Theresa May and Brexit secretary David Davis of being closet amagogotya. That is probably accurate: as Britain’s point-people in the negotiations, these two sense that cattle-killing might not be a winning strategy.

Sillitoe says it’s wrong to dismiss cargo cultists as “irrational and deluded people”. In fact, he writes, “Cargo cults are a rational indigenous response to traumatic culture contact with western society.” Comical as the participants might seem, “they are neither illogical nor stupid”.

Certainly the Conservative cult follows its own logic. The aim isn’t simply to reduce immigration or boost the economy. Rather, Brexit reaffirms the tribe’s ancestral values against a disappointing modernity. The difficulty of Brexiting is part of the appeal: only a great tribe can renew itself through sacrifice. The stalling of talks with the EU is welcomed as a ritual re-enactment of Britain’s past glorious conflicts. Hence the ovations for any speaker at last month’s Conservative conference who urged walking out with no deal.

A recent blog by Pete North, a founder of the Leave Alliance, beautifully sums up many of these attitudes. North, who favoured staying in the European single market, predicts Brexit will send Britain into “a 10-year recession”. He writes: “After years of the left bleating about austerity, they are about to find out what it actually means.” And yet, he continues, “My gut instinct tells me that culturally it will be a vast improvement on the status quo.” He says modern Britons have become “spoiled and self-indulgent . . . in the absence of any real challenges or imperatives to grow as a people”. As the psychiatrist says of the TV character Basil Fawlty, there’s enough material here for an entire conference.

After the cattle-killing, many Xhosa starved to death, while flocks of vultures reportedly watched from above. Refugees who fled to the British Cape Colony were forced into serf-like labour contracts. But Nongqawuse lived on for another 40 years, albeit in exile, under a changed name.

Sunday, 4 December 2016

Why bhakti in politics is bad for democracy

Ramachandra Guha in The Hindustan Times

Back in 2005, a knowledgeable Gujarati journalist wrote of how ‘Narendra Modi thinks a detergent named development will wash away the memory of 2002’. While focusing on new infrastructure and industrial projects in his state, the then chief minister of Gujarat launched what the journalist called ‘a massive self-publicity drive’, publishing calendars, booklets and posters where his own photograph appeared prominently alongside words and statistics speaking of Gujarat’s achievements under his leadership. ‘Modi has made sure that in Gujarat no one can escape noticing him,’ remarked the journalist.

Since May 2014, this self-publicity drive has been extended to the nation as a whole. In fact, the process began before the general elections, when, through social media and his speeches, Narendra Modi successfully projected himself as the sole and singular alternative to a (visibly) corrupt UPA regime. The BJP, a party previously opposed to ‘vyakti puja’, succumbed to the power of Modi’s personality. Since his swearing-in as Prime Minister, the government has done what the party did before it: totally subordinated itself to the will, and occasionally the whim, of a single individual.

Hero-worship is not uncommon in India. Indeed, we tend to excessively venerate high achievers in many fields. Consider the extraordinarily large and devoted fan following of Sachin Tendulkar and Lata Mangeshkar. These fans see their icons as flawless in a way fans in other countries do not. In America, Bob Dylan has many admirers but also more than a few critics. The same is true of the British tennis player Andy Murray. But in public discourse in India, criticism of Sachin and Lata is extremely rare. When offered, it tends to be met with vituperative abuse, not by rational or reasoned rebuttal.

The hero-worship of sportspeople is merely silly. But the hero-worship of politicians is inimical to democracy. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu were epicentres of progressive social reform, whose activists promoted caste and gender equality, rational thinking, and individual rights. Yet in more recent years, Maharashra has seen the cult of Bal Thackeray, Tamil Nadu the cult of J Jayalalithaa. In each case, the power of the State was (in Jayalalithaa’s case still is) put in service of this personality cult, with harassment and intimidation of critics being common.

However, at a nation-wide level the cult of Narendra Modi has had only one predecessor — that of Indira Gandhi. Thus now, as then, ruling party politicians demand that citizens see the Prime Minister as embodying not just the party or the government, but the nation itself. Millions of devotees on social media (as well as quite a few journalists) have succumbed to the most extreme form of hero-worship. More worryingly, one senior cabinet minister has called Narendra Modi a Messiah. A chief minister has insinuated that anyone who criticises the Prime Minister’s policies is anti-national. Meanwhile, as in Indira Gandhi’s time, the government’s publicity wing, as well as AIR and Doordarshan, works overtime to broadcast the Prime Minister’s image and achievements.

While viewing the promotion of this cult of Narendra Modi, I have been reminded of two texts by long-dead thinker-politicians, both (sadly) still relevant. The first is an essay published by Jawaharlal Nehru in 1937 under the pen-name of ‘Chanakya’. Here Nehru, referring to himself in the third person (as Modi often does now), remarked: ‘Jawaharlal cannot become a fascist. Yet he has all the makings of a dictator in him — a vast popularity, a strong will directed to a well-defined purpose, energy, pride, organisational capacity, ability, hardness, and, with all his love of the crowd, an intolerance of others and a certain contempt for the weak and the inefficient.’

Nehru was here issuing a warning to himself. Twelve years later, in his remarkable last speech to the Constituent Assembly, BR Ambedkar issued a warning to all Indians, when, invoking John Stuart Mill, he asked them not ‘to lay their liberties at the feet of even a great man, or to trust him with powers which enable him to subvert their institutions’. There was ‘nothing wrong’, said Ambedkar, ‘in being grateful to great men who have rendered life-long services to the country. But there are limits to gratefulness.’ He worried that in India, ‘Bhakti or what may be called the path of devotion or hero-worship, plays a part in its politics unequalled in magnitude by the part it plays in the politics of any other country in the world. Bhakti in religion may be a road to the salvation of the soul. But in politics, Bhakti or hero-worship is a sure road to degradation and to eventual dictatorship.’

These remarks uncannily anticipated the cult of Indira Gandhi and the Emergency. As I have written in these columns before, Indian democracy is now too robust to be destroyed by a single individual. But it can still be severely damaged. That is why this personality cult of Narendra Modi must be challenged (and checked) before it goes much further.

Later this week we shall observe the 60th anniversary of BR Ambedkar’s death. Some well-meaning (and brave) member of the Prime Minister’s inner circle should bring Ambedkar’s speech of 1949 to his attention. And perhaps Nehru’s pseudonymous article of 1937 too.

Back in 2005, a knowledgeable Gujarati journalist wrote of how ‘Narendra Modi thinks a detergent named development will wash away the memory of 2002’. While focusing on new infrastructure and industrial projects in his state, the then chief minister of Gujarat launched what the journalist called ‘a massive self-publicity drive’, publishing calendars, booklets and posters where his own photograph appeared prominently alongside words and statistics speaking of Gujarat’s achievements under his leadership. ‘Modi has made sure that in Gujarat no one can escape noticing him,’ remarked the journalist.

Since May 2014, this self-publicity drive has been extended to the nation as a whole. In fact, the process began before the general elections, when, through social media and his speeches, Narendra Modi successfully projected himself as the sole and singular alternative to a (visibly) corrupt UPA regime. The BJP, a party previously opposed to ‘vyakti puja’, succumbed to the power of Modi’s personality. Since his swearing-in as Prime Minister, the government has done what the party did before it: totally subordinated itself to the will, and occasionally the whim, of a single individual.

Hero-worship is not uncommon in India. Indeed, we tend to excessively venerate high achievers in many fields. Consider the extraordinarily large and devoted fan following of Sachin Tendulkar and Lata Mangeshkar. These fans see their icons as flawless in a way fans in other countries do not. In America, Bob Dylan has many admirers but also more than a few critics. The same is true of the British tennis player Andy Murray. But in public discourse in India, criticism of Sachin and Lata is extremely rare. When offered, it tends to be met with vituperative abuse, not by rational or reasoned rebuttal.

The hero-worship of sportspeople is merely silly. But the hero-worship of politicians is inimical to democracy. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu were epicentres of progressive social reform, whose activists promoted caste and gender equality, rational thinking, and individual rights. Yet in more recent years, Maharashra has seen the cult of Bal Thackeray, Tamil Nadu the cult of J Jayalalithaa. In each case, the power of the State was (in Jayalalithaa’s case still is) put in service of this personality cult, with harassment and intimidation of critics being common.

However, at a nation-wide level the cult of Narendra Modi has had only one predecessor — that of Indira Gandhi. Thus now, as then, ruling party politicians demand that citizens see the Prime Minister as embodying not just the party or the government, but the nation itself. Millions of devotees on social media (as well as quite a few journalists) have succumbed to the most extreme form of hero-worship. More worryingly, one senior cabinet minister has called Narendra Modi a Messiah. A chief minister has insinuated that anyone who criticises the Prime Minister’s policies is anti-national. Meanwhile, as in Indira Gandhi’s time, the government’s publicity wing, as well as AIR and Doordarshan, works overtime to broadcast the Prime Minister’s image and achievements.

While viewing the promotion of this cult of Narendra Modi, I have been reminded of two texts by long-dead thinker-politicians, both (sadly) still relevant. The first is an essay published by Jawaharlal Nehru in 1937 under the pen-name of ‘Chanakya’. Here Nehru, referring to himself in the third person (as Modi often does now), remarked: ‘Jawaharlal cannot become a fascist. Yet he has all the makings of a dictator in him — a vast popularity, a strong will directed to a well-defined purpose, energy, pride, organisational capacity, ability, hardness, and, with all his love of the crowd, an intolerance of others and a certain contempt for the weak and the inefficient.’

Nehru was here issuing a warning to himself. Twelve years later, in his remarkable last speech to the Constituent Assembly, BR Ambedkar issued a warning to all Indians, when, invoking John Stuart Mill, he asked them not ‘to lay their liberties at the feet of even a great man, or to trust him with powers which enable him to subvert their institutions’. There was ‘nothing wrong’, said Ambedkar, ‘in being grateful to great men who have rendered life-long services to the country. But there are limits to gratefulness.’ He worried that in India, ‘Bhakti or what may be called the path of devotion or hero-worship, plays a part in its politics unequalled in magnitude by the part it plays in the politics of any other country in the world. Bhakti in religion may be a road to the salvation of the soul. But in politics, Bhakti or hero-worship is a sure road to degradation and to eventual dictatorship.’

These remarks uncannily anticipated the cult of Indira Gandhi and the Emergency. As I have written in these columns before, Indian democracy is now too robust to be destroyed by a single individual. But it can still be severely damaged. That is why this personality cult of Narendra Modi must be challenged (and checked) before it goes much further.

Later this week we shall observe the 60th anniversary of BR Ambedkar’s death. Some well-meaning (and brave) member of the Prime Minister’s inner circle should bring Ambedkar’s speech of 1949 to his attention. And perhaps Nehru’s pseudonymous article of 1937 too.

Saturday, 9 November 2013

Soldier worship blinds Britain to the grim reality of war

A Royal Marine's murder of a wounded Afghan in his custody lays bare the truth of military campaigns

'We should not feel compelled to point out that brave men and women are fighting in Afghanistan to secure our safety every time the military is mentioned.' Photograph: Getty Images

With the official Remembrance Day ceremony closing in, and soldier worship about to hit its tedious annual peak, the public have been given an unexpected glimpse of war's unsanitised face. A Royal Marine has been convicted of murdering a wounded Afghan in his custody. Two marines were acquitted.

While the public has for 12 years been told otherwise, the Afghan occupation is not simply a case of good guys and bad guys. Nevertheless, tired references to "bad apples" will now flow. The Ministry of Defence will repeatedly and frantically highlight the supposed "good work" the troops have been doing in the smoking ruins of Afghanistan. A stock statement will be released by the MoD about military values and high standards of behaviour. Allegations of law-breaking, they will tell us, are investigated thoroughly and can result in disciplinary action up to and including court martial, discharge and prison. And all of this will obscure rather than address the issue.

From the outset this episode has been written through with the brand of self-delusion that has come to typify the "good war". The original arrest of seven marines in 2012, following the discovery of footage on a laptop, sparked an indignant Facebook campaign to "Support the 7 Royal Marine Commandos arrested for murder in Afghanistan". To date, it has attracted 63,000 "likes". If nothing else, this highlights how a section of society can leap to the defence of servicemen long before the facts are known.

It is my view that Royal Marine commandos are the best light role infantry in the world – bar none. Bootnecks, as they are colloquially known, are capable, professional and robust soldiers. But I can say all this without once gushing about "heroes" and without ever once needing to shy away from an uncomfortable truth simply because it happens to concern soldiers.

We should not feel compelled to point out that those brave men and women are fighting in Afghanistan to secure our safety every time the military is mentioned. First, because it is not true that they are; and second, because such blustering at the merest glimpse of camouflage clothing is an obvious and embarrassing capitulation to dogma.

The question at the core of this is not how we can most tastefully play down criminal acts carried out by the services. The question we ought to be brave enough to ask is: why is there such surprise when atrocities occur? There is a belief in moralistic sections of the political left and the more dumbly macho sections of the political right that soldiers, as a rule, relish killing people. Both sides are wrong – a trained killer does not equate to mindless robot.

To understand why an occupying soldier turns to vigilantism and murder, we can do worse than look at their daily experience, which can never be divorced from the over-arching political context. Killings like this most often occur when soldiers have lost a comrade or comrades. They lose comrades because they are in a war. Killings like these can reasonably expected to be carried out by all sides in any conflict.

What radicalises soldiers then is not too far from what radicalises lone wolf killers, terror cells and drone strike orphans: the impact of policy on an individual and the people you care about. Marine A, now convicted, was a 39-year-old senior non-commissioned officer. He had done six tours of Afghanistan as an infantryman. He is likely to have experienced countless engagements and lost various friends in a failing war. This does not excuse his actions, but why should he and his fellow marines' callous attitude to death, shown in the transcripts of the helmet camera recording of the event, be a surprise?

When a political decision is taken that puts men who are primed for violence into a war, bad things will happen. This is another reason to make sure that war is the very last resort and not, as in the case of the post-9/11 wars, something that is engaged in lightly, in a spirit of hubris or in the pursuit of narrow interests.

At its core, this is a problem at the political level, which can only be resolved or avoided at the political level. It does not diminish the responsibility of the killers to say the issue is more complex than bad apples letting the side down. The culture of irrational and uncritical soldier worship serves only to blind us to the realities of war and occupation – and this contrived, blinding effect, I have long suspected, is rather the point of lionising the military.

Monday, 11 February 2013

Thursday, 6 September 2012

You can't dance to atheism

Any doctrine that actually works to hold society together is indistinguishable from a religion. It needs its rituals and its myths

'In America the myth of a particular sort of extreme individualism is inseparable from the myths of a particular sort of America whose history has been invented in almost every detail.' Photograph: Ethan Miller/Getty Images

I finished the series of articles I wrote on Robert Bellah's Religion in Human Evolutionwith a definition – a religion is a philosophy that makes you dance. It pleased me because the book itself can be read as a history of how philosophy grew from dance. But is it any use?

The great difficulty of definitions like mine is that they leave the content of religions entirely to one side. We are still enough of the heirs of Christendom to feel that religions must involve doctrines, heresies, and a commitment to supernatural realism. The trouble is that a definition with doctrines, heresies, and supernaturalism fits many varieties of atheism just as well. You will object that atheism bans, by definition, any belief in the supernatural. Yet almost all sophisticated religions ban at an intellectual level all kinds of belief which sustain them in practice. Buddhists worship; Muslims have idols. "Theological incorrectness" is found wherever you look for it.

And atheism can be just as theologically incorrect: today's paper told me that: "our bodies are built and controlled by far fewer genes than scientists had expected". The metaphors of "building" and "controlling" have here taken a concrete form that makes them palpably untrue. Genes don't do either thing. It seems to me that a belief in tiny invisible all-controlling entities is precisely a belief in the supernatural, yet that is the form in which entirely naturalistic genetics is widely understood in our culture. Religion can't really be about doctrine and heresy either, because these concepts don't make sense in pre-literate cultures. You can even ask whether the concept of "supernaturalism" makes any sense in most of the world without a developed idea of scientific naturalism, and scientific laws, that would stand for its opposite.

The serious weakness of my definition is that philosophy itself is a very late development and not one that has really caught on. As Bertrand Russell observed, many people would rather die than think, and most do. So maybe it would be better to say that religion is a myth that you can dance to. This is useful because it suggests that atheism is not a religion as you can't dance to it. There's no shortage of atheist myths – in the sense of historically incorrect statements which are believed for their moral value and because it's thought that society will fall apart if they're abandoned. The comments here are full of them. But they are no longer danceable.

There aren't any overwhelming and inspiring collective atheist rituals. I don't mean that these can't exist. Olof Palme's funeral procession was one unforgettable example. But they don't exist today. Possibly, the London demonstration against Pope Benedict would qualify but in terms of numbers it was wholly insignificant compared with the crowds that he drew, or that flock to church every Sunday.

Against this point the committed atheist replies exactly as a liberal protestant would have done 20 years ago: bums on pews don't matter; he or she is in the business of truth, not numbers, and the truth must in the course of time prevail. I don't believe this. I don't believe it in either case. Individualism without some myth of the collective is quite powerless. This is clearly illustrated by the Tea Party in America where the myth of a particular sort of extreme individualism is inseparable from the myths of a particular sort of America whose history has been invented in almost every detail.

If I'm right, then liberal, individualistic atheism is impossible as an organising principle of society because any doctrine that actually works to hold society together is indistinguishable from a religion. It needs its rituals and it needs its myths. A philosophy will grow around it in due course. Now perhaps you can have, at least on a small scale, a society committed to the principles of rational and tolerant disagreement and the sovereignty of reason. But what you end up with then isn't some rational Athens of the mind. It's Glastonbury.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)