'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label ignorance. Show all posts

Showing posts with label ignorance. Show all posts

Tuesday, 24 October 2023

Tuesday, 18 April 2023

Saturday, 6 February 2021

The parable of John Rawls

Janan Ganesh in The FT

In the latest Pixar film, Soul, every human life starts out as a blank slate in a cosmic holding pen. Not until clerks ascribe personalities and vocations does the corporeal world open. As all souls are at their mercy, there is fairness of a kind. There is also chilling caprice. And so Pixar cuts the stakes by ensuring that each endowment is benign. No one ends up with dire impairments or unmarketable talents in the “Great Before”.

Kind as he was (a wry Isaiah Berlin, it is said, likened him to Christ), John Rawls would have deplored the cop-out. This year is the 50th anniversary of the most important tract of political thought in the last century or so. To tweak the old line about Plato, much subsequent work in the field amounts to footnotes to A Theory of Justice. Only some of this has to do with its conclusions. The method that yielded them was nearly as vivid.

Rawls asked us to picture the world we should like to enter if we had no warning of our talents. Nor, either, of our looks, sex, parents or even tastes. Don this “veil of ignorance”, he said, and we would maximise the lot of the worst-off, lest that turned out to be us. As we brave our birth into the unknown, it is not the average outcome that troubles us.

From there, he drew principles. A person’s liberties, which should go as far as is consistent with those of others, can’t be infringed. This is true even if the general welfare demands it. As for material things, inequality is only allowed insofar as it lifts the absolute level of the poorest. Some extra reward for the hyper-productive: yes. Flash-trading or Lionel Messi’s leaked contract: a vast no. Each of these rules puts a floor — civic and economic — under all humans.

True, the phrase-making helped (“the perspective of eternity”). So did the timing: 1971 was the Keynesian Eden, before Opec grew less obliging. But it was the depth and novelty of Rawls’s thought that brought him reluctant stardom.

Even those who denied that he had “won” allowed that he dominated. Utilitarians, once-ascendant in their stress on the general, said he made a God of the individual. The right, sure that they would act differently under the veil, asked if this shy scholar had ever met a gambler. But he was their reference point. And others’ too. A Theory might be the densest book to have sold an alleged 300,000 copies in the US alone. It triumphed.

And it failed. Soon after it was published, the course of the west turned right. The position of the worst-off receded as a test of the good society. Robert Nozick, Rawls’s libertarian Harvard peer, seemed the more relevant theorist. It was a neoliberal world that saw both men out in 2002.

An un-public intellectual, Rawls never let on whether he cared. Revisions to his theory, and their forewords, suggest a man under siege, but from academic quibbles not earthly events. For a reader, the joy of the book is in tracking a first-class mind as it husbands a thought from conception to expression. Presumably that, not averting Reaganism, was the author’s aim too.

And still the arc of his life captures a familiar theme. It is the ubiquity of disappointment — even, or especially, among the highest achievers. Precisely because they are capable of so much, some measure of frustration is their destiny. I think of Tony Blair, thrice-elected and still, post-Brexit, somehow defeated. (Sunset Boulevard, so good on faded actors, should be about ex-politicians.) Or of friends who have made fortunes but sense, and mind, that no one esteems or much cares about business.

The writer Blake Bailey tells an arresting story about Gore Vidal. The Sage of Amalfi was successful across all literary forms save poetry. He was rich enough to command one of the grandest residential views on Earth. If he hadn’t convinced Americans to ditch their empire or elect him to office, these were hardly disgraces. On that Tyrrhenian terrace, though, when a friend asked what more he could want, he said he wanted “200 million people” to “change their minds”. At some level, however mild his soul, so must have Rawls.

Sunday, 24 May 2020

Wednesday, 13 February 2019

Monday, 5 December 2016

Who am I? Swami Sarvapriyananda speaking at IIT Kanpur

Part 1

Part 2

Tips on Meditation

Three great powers within us

How to create the eternal witness

Wednesday, 30 September 2015

How the banks ignored the lessons of the crash

Joris Luyendijk in The Guardian

Ask people where they were on 9/11, and most have a memory to share. Ask where they were when Lehman Brothers collapsed, and many will struggle even to remember the correct year. The 158-year-old Wall Street bank filed for bankruptcy on 15 September 2008. As the news broke, insiders experienced an atmosphere of unprecedented panic. One former investment banker recalled: “I thought: so this is what the threat of war must feel like. I remember looking out of the window and seeing the buses drive by. People everywhere going through a normal working day – or so they thought. I realised: they have no idea. I called my father from the office to tell him to transfer all his savings to a safer bank. Going home that day, I was genuinely terrified.”

A veteran at a small credit rating agency who spent his whole career in the City of London told me with genuine emotion: “It was terrifying. Absolutely terrifying. We came so close to a global meltdown.” He had been on holiday in the week Lehman went bust. “I remember opening up the paper every day and going: ‘Oh my God.’ I was on my BlackBerry following events. Confusion, embarrassment, incredulity ... I went through the whole gamut of human emotions. At some point my wife threatened to throw my BlackBerry in the lake if I didn’t stop reading on my phone. I couldn’t stop.”

Other financial workers in the City, who were at their desks after Lehman defaulted, described colleagues sitting frozen before their screens, paralysed – unable to act even when there was easy money to be made. Things were looking so bad, they said, that some got on the phone to their families: “Get as much money from the ATM as you can.” “Rush to the supermarket to hoard food.” “Buy gold.” “Get everything ready to evacuate the kids to the country.” As they recalled those days, there was often a note of shame in their voices, as if they felt humiliated by the memory of their vulnerability. Even some of the most macho traders became visibly uncomfortable. One said to me in a grim voice: “That was scary, mate. I mean, not film scary. Really scary.”

I spent two years, from 2011 to 2013, interviewing about 200 bankers and financial workers as part of an investigation into banking culture in the City of London after the crash. Not everyone I spoke to had been so terrified in the days and weeks after Lehman collapsed. But the ones who had phoned their families in panic explained to me that what they were afraid of was the domino effect. The collapse of a global megabank such as Lehman could cause the financial system to come to a halt, seize up and then implode. Not only would this mean that we could no longer withdraw our money from banks, it would also mean that lines of credit would stop. As the fund manager George Cooper put it in his book The Origin of Financial Crises: “This financial crisis came perilously close to causing a systemic failure of the global financial system. Had this occurred, global trade would have ceased to function within a very short period of time.” Remember that this is the age of just-in-time inventory management, Cooper added – meaning supermarkets have very small stocks. With impeccable understatement, he said: “It is sobering to contemplate the consequences of interrupting food supplies to the world’s major cities for even a few days.”

These were the dominos threatening to fall in 2008. The next tile would be hundreds of millions of people worldwide all learning at the same time that they had lost access to their bank accounts and that supplies to their supermarkets, pharmacies and petrol stations had frozen. The TV images that have come to define this whole episode – defeated-looking Lehman employees carrying boxes of their belongings through Wall Street – have become objects of satire. As if it were only a matter of a few hundred overpaid people losing their jobs: Look at the Masters of the Universe now, brought down to our level!

In reality, those cardboard box-carrying bankers were the beginning of what could very well have been a genuine breakdown of society. Although we did not quite fall off the edge after the crash in the way some bankers were anticipating, the painful effects are still being felt in almost every sector. At this distance, however, seven years on, it’s hard to see what has changed.

A typical education in the west leaves you with more insight into ancient Rome or Egypt than into our financial system – and while there are plenty of books and DVDs for lay people about, say, quantum mechanics, evolution or the human genome, before the crash there was virtually nothing to explain finance to outsiders in accessible language. The City, as John Lanchester put it in his book about the 2008 crash, Whoops!, is still “a far-off country of which we know little”.

As a result, ordinary people trying to form an opinion about finance over the past decades have had very little to go on, and many seem to have latched on to the images provided by films and TV.

The British stereotype of the boring banker began to change in the 80s when finance was deregulated. Following Ronald Reagan’s dictum, “Government is not the solution to the problem, it is the problem”, banks were allowed to unite under one roof activities that regulation had previously required to be divided between separate firms and banks. They were able to grow to sizes many times bigger than a country’s GDP – the assumption being that the market would be self-regulating. The changes also meant that bankers became immensely powerful. Hollywood provided the City with a new hero: the financier Gordon Gekko, from Oliver Stone’s 1987 film Wall Street, who brought us the phrase “Greed is good”. In his portrait of bond traders’ raging ambition, Bonfire of the Vanities, novelist Tom Wolfe coined the term “Masters of the Universe”.

It all seemed innocent entertainment, before 2008: tales about a far-off country where boys behaved badly, scandalously even, but above all, reassuringly far away from the comfort and safety of our own homes, something like watching a Quentin Tarantino film or an episode of The Sopranos. This was the era when a Labour chancellor, Gordon Brown, could give a speech to a gathering of bankers and asset managers and tell them: “The financial services sector in Britain, and the City of London at the centre of it, is a great example of a highly skilled, high value-added, talent-driven industry that shows how we can excel in a world of global competition. Britain needs more of the vigour, ingenuity and aspiration that you already demonstrate that is the hallmark of your success.”

Those words were spoken in 2007, and a year later the world found itself in the middle of the biggest financial panic since the 1930s. In the end, it was only through a combination of pure luck, extremely expensive nationalisations and bailouts, the lowest interest rates in recorded history plus an ongoing experiment in mass money printing, that total meltdown was averted.

The post-Lehman panic was followed by a wave of investigations and reconstructions by journalists, writers and politicians. More than 300 books have been published about the crash in English alone. Every western country held extensive hearings and produced detailed recommendations. Everything you need to know about what is wrong with finance and the banks today is in their reports; the problem is that there is so much more that needs to be explained.

Most areas inside banking had little or nothing to do with the crash, while many players outside banking bore a heavy responsibility, too, including insurers, credit rating agencies, accountancy firms, financial law firms, central banks, regulators and politicians. Investors such as pension funds had been egging the banks on to make more profits by taking more risk. Unless you had a firm understanding of finance, the causes of the crash were very unclear, and this must be part of the reason why the clearest and most urgent lesson of all would get lost or buried: the financial system itself had become dangerously flawed.

After the crash of 2008, ignorance among the general public, reticence among complicit mainstream politicians and a deeply skewed and sensationalist portrayal of finance in the mass media conspired to create the narrative that the crash was caused by greed or by some other character flaw in individual bankers: psychopathy, gambling addiction or cocaine use. (A whole genre of City memoirs sprang up with titles such as Binge Trading: The Real Inside Story of Cash, Cocaine and Corruption in the City. Gordon Gekko returned for a sequel, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, and Leonardo di Caprio scored an immense hit playing the title role in The Wolf of Wall Street, about a whoring and cocaine-snorting financial fraudster.)

From there it was a small step to the notion that we can fix finance by getting rid of the “jerks”, as the plain speaking former Barclays CEO Bob Diamond put it. When Diamond was forced to resign in July 2012 over a scandal involving interest rate rigging by his traders, his successor, Antony Jenkins, also promised to focus on changing the culture. And so the same banks that brought us the mess of 2008 eagerly embraced the need for cultural change – which alone should arouse our suspicions. If there is one recurring theme in the many conversations I had with City insiders, it was the need for structural rather than cultural change; not so much different bankers, but a different system.

“Sometimes I feel as if finance has reacted to the crisis the way a motorist might after a near-accident,” said the City veteran at a small credit rating agency whose wife had almost chucked his phone into a lake at the height of the panic. “There is the adrenaline surge directly after the lucky escape, followed by the huge shock when you realise what could have happened. But as the journey continues and the scene recedes in the rear-view mirror, you tell yourself: maybe it wasn’t that bad. The memory of your panic fades, and you even begin to misremember what happened. Was it really that bad?”

He was a soft-spoken man, the sort to send a text message if he is going to be five minutes late to a meeting. But now he was really angry: “If you had told people at the height of the crisis that years later we’d have had no fundamental changes, nobody would have believed you. Such was the panic and fear. But here we are. It’s back to business as usual. We went from ‘We nearly died from this’ to ‘We survived this’.”

The City is governed by a code of silence and fear of publicity; those caught talking to the press without a PR officer present could be sacked or sued. But once I had persuaded City insiders to talk (always and only on condition of anonymity), they were remarkably forthcoming.

“I have the wrong accent and I went to a shit school,” said one City veteran, after explaining that for many years he had made millions at a top bank only to move to an even better-paying hedge fund. “Forty years ago, I wouldn’t even have been given an interview in the City. Finance today is fiercely meritocratic. Doesn’t matter if you’re gay or black or working class, if you can do something better than the other person, you’ll move up.”

He was a mathematician by training, and his direct manner reminded me of stallholders at the biggest open market in my hometown of Amsterdam – tough guys with a highly developed mistrust of pretentiousness. He fuelled himself with Diet Coke and coffee and teased me for ordering cranberry juice. Before he was recruited by the bank in the early 1990s, he had taught at a university; his only idea of an investment bank was based on two books he had read: Liar’s Poker by Michael Lewis and Barbarians at the Gate by Bryan Burrough and John Helyar. “Traders as loud, crass, bad-mouthed, macho dickheads. The sort of guys with red braces who shout ‘buy, buy, sell, sell’ into their phones and have eating competitions.” Many outsiders still believe that these are the people occupying the top positions in big banks, he said, and taking the biggest risks. “That’s over,” he told me. “Some of the best traders are now women. Totally unassuming, cerebral and talented. Trading is no longer a balls job. It’s a brains job. To be sure, the kind of maths traders now have to be able to do is not of the wildly hard variety. But it requires real skills in that area.”

He described the basic flaw in the banking system as it has evolved over the past decades: other people’s money. Until deregulation began to liberate finance from the constraints placed on it after the last major crash in the 1930s, risky banking in the City was carried out in firms that were organised as partnerships, which were not listed on the stock exchange. The partners owned and ran the firm – and when things went wrong, they were liable. Hence the system of bonuses: if you put your personal fortune on the line and things go well, it stands to reason that you deserve a big bonus. Because if things go the other way, you are personally liable for the losses.

Back in the days when his bank was still a partnership, the former banker had drawn on his gift for maths to build a complex financial product that he thought was very clever. “I was very new and maybe a bit cocky,” he said. “So I went over to the head of trading and showed it to him, saying, ‘Look, we can make a lot of money with this.’ The head of trading was a partner in the traditional sense. He looked at me and replied: ‘Don’t forget, this is my money you’re fucking with.’”

The problem with the way banks are now organised is not that they take risks – that is their job. The problem with today’s banks is that those who accept the risks are no longer those who get stuck with the bill.

A bank that is listed on the stock market loses control to the new owners; that is, the shareholders. When these shareholders, which can include insurers, wealthy dynasties or pension funds, start demanding ever greater profits, then greater profits are what you have to deliver. In 2007, in an inadvertent moment of candour, the then CEO of the megabank Citigroup, Charles O Prince, summarised this relationship: “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.”

This dynamic became all the more dangerous as globalisation began to create a single market for finance. Not only were partnerships allowed to be listed on the stock exchange or taken over by a publicly listed bank, they were also allowed to go on a global shopping spree. Wave after wave of mergers and acquisitions meant banks could generate higher profits than the GDPs of their host countries, resulting in the institutions that we now know as “too big to fail” – so big that if they go bust, they can bring down the system with them. When excessive risk turns sour, it’s the taxpayer who suffers.

In a functioning free market system, incompetence and recklessness are punished by failure and bankruptcy. But there is currently no functioning free market at the centre of the global free market system. I heard City workers scoff at the employees of banks that cannot be allowed to fail – calling them overpaid civil servants who play a game they cannot lose. Risk-taking at a bank that will always be saved, they said, is like playing Russian roulette with someone else’s head.

In the old days, veterans told me, there was an office party almost every Friday: celebrating the anniversary of someone who had stayed with the firm for 20 years or longer. That is all over now, and in its place has come a hire-and-fire culture characterised by an absence of loyalty on either side. Employment in the City is now a purely transactional affair. It is exceedingly rare to find people who have stayed with the same bank for their entire career.

Many of the insiders I spoke to had stories about abrupt sackings: You get a call from a colleague, saying: “Look, could you do me a favour and get my coat and bag?” She is standing outside with a blocked security pass. One morning, you swipe your pass only to hear a beep and find your entrance barred. You turn to the receptionist who says, after a glance at her computer screen, “Would you please have a seat over there until somebody comes to fetch you?”

In the City, sudden dismissals of this kind have a name: “executions”. Add to these the quarterly “waves” when headquarters decides to reduce headcount and a certain percentage of staff worldwide are given the sack, all on one day. Some banks operate a “cull”. Every year, prestigious banks such as Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan routinely fire their least profitable staff. “When the cull comes ...” people would say, or: “Oh yes, we cull.”

“When you can be out of the door in five minutes, your horizon becomes five minutes,” one City worker told me. Another asked: “Why would I treat my bank any better than my bank treats me?”

If the threat of being culled influenced bankers’ behaviour through fear, there were also powerful motivations. Deregulation has allowed perverse incentives into the very fabric of global finance. People are faced with immense temptations to take risks with their bank’s capital or reputation, knowing that if they don’t act on them, their colleague across the desk will.

Before the deregulation of the 80s and 90s, the City was far from perfect: it was a snobbish, antisemitic and misogynistic place. But the City – and Wall Street – of old was a world that Gus Levy, head of Goldman Sachs in the 70s, famously described as “long term greedy”; you made money with your client and your firm. Because partners were personally liable, they had an interest in keeping their firm on a manageable scale and making sure their employees told them of any risks. In a few decades, this system has evolved into one that Levy called “short term greedy”; you make money at the expense of the client, of the bank, of the shareholder or of the taxpayer. This did not happen because bankers suddenly became evil, but because the incentives fundamentally changed.

Until the mid 80s, the London Stock Exchange’s motto was dictum meum pactum, “my word is my bond”. These days the governing principle is caveat emptor, or “buyer beware” – it is effectively up to the professional investor to figure out what the bank is offering. As one builder of complex financial products explained to me: “You have got to read the small print. You need to bring in a lawyer who explains it to you before you buy these things.”

Perhaps the most terrifying interview of all the 200 I recorded was with a senior regulator. It was not only what he said but how he said it: as if the status quo was simply unassailable. Ultimately, he explained, regulators – the government agencies that ensure the financial sector is safe and compliant – rely on self-declaration; what is presented by a bank’s internal management. The trouble, he said with a calm smile, is that a bank’s internal management often doesn’t know what’s going on because banks today are so vast and complex. He did not think he had ever been deliberately lied to, although he acknowledged that, obviously, he couldn’t know for sure. “The real threat is not a bank’s management hiding things from us, it’s the management not knowing themselves what the risks are.”

He talked about the culture of fear and how people are not managing their actions for the benefit of their bank. Instead, “they are managing their career”. He believed that the crash had been more “cock-up than conspiracy”. Bank management is in conflict, he pointed out: “What is good for the long term of the bank or the country may not be what is best for their own short-term career or bonus.”

If the problem with finance is perverse incentives, then the insistence on greed as the cause for the crash is part of the problem. There is a lot of greed in the City, as there is elsewhere in society. But if you blame the crash on character flaws in individuals you imply that the system itself is fine, all we need to do is to smoke out the crooks, the gambling addicts, the coke-snorters, the sexists, the psychopaths. Human beings always have at least some scope for choice, hence the differences in culture between banks. Still, human behaviour is largely determined by incentives, and in the current set-up, these are sending individual bankers, desks or divisions within banks – as well as the banks themselves – in the wrong direction.

How hard would it be to change those incentives? From the viewpoint of those I interviewed, not hard at all. First of all, banks could be chopped up into units that can safely go bust – meaning they could never blackmail us again. Banks should not have multiple activities going on under one roof with inherent conflicts of interest. Banks should not be allowed to build, sell or own overly complex financial products – clients should be able to comprehend what they buy and investors understand the balance sheet. Finally, the penalty should land on the same head as the bonus, meaning nobody should have more reason to lie awake at night worrying over the risks to the bank’s capital or reputation than the bankers themselves. You might expect all major political parties to have come out by now with their vision of a stable and productive financial sector. But this is not what has happened.

Not that there has been no reform. Banks are taxed when they get beyond a certain size, for example, and all banks must now finance a larger part of their risks with equity rather than borrowed money. American banks are banned from using their own capital to speculate and invest in the markets, and the European commission, or national governments, have forced a few banks to shrink or sell off their investment bank activities – the Dutch bank ING, for example, was told to sell off its insurance arm, ING Direct. But change has been largely cosmetic, leaving the sector’s basic architecture intact. If a bank collapses, the new European banking union – set up in 2012 to transfer banking policy from a national to a European level – is meant to step in and wind it down in an orderly fashion. But who is propping up that European banking union, if several banks should fail at the same time? The taxpayer. A bonus cap in banking was introduced by the EU, so instead of paying widely publicised million-pound bonuses, banks now simply offer higher salaries.

Perhaps the most promising change in the UK is the so-called “senior person regime” that makes it possible to prosecute bankers for reckless behaviour – but only after they have wrecked their bank. Virtually all big banks remain publicly listed or are doing everything they can to get back on the stock exchange. They have never allowed staff to talk openly about what went wrong before 2008 and why. The code of silence remains intact. The banks have not sacked the accountancy firms or credit rating agencies that failed to raise the alarm over the erroneous or misleading items on their balance sheets. Banks have certainly not joined hands to fight for a globally enforced increase in capital buffers (the minimum capital they are required to hold), which could help them absorb and survive severe losses. Indeed, they have spent millions lobbying to keep any increase in buffers as low as possible.

“Back to business as usual.” This is how many interviewees described the post-crash atmosphere in the City. As the senior regulator put it with chilling equanimity: “Is the sector fixed, after the crisis? I don’t think so.” What we have now, he added, is “what you get with free-market capitalism – consolidation of all wealth into fewer and fewer banks, which end up dividing up the market as a cartel.”

When it comes to global finance, the most startling news isn’t news at all; the important facts have been known for a long time among insiders. The problem goes much deeper: the sector has become immune to exposure.

“If I had a million pounds for every time I have heard a possible reform opposed because ‘it wouldn’t have prevented Northern Rock or Lehman Brothers going bust’, I might now have enough money to bail out a bank,” the Financial Times columnist John Kay wrote in 2013. “The objective of reform is not to prevent Northern Rock or Lehman going bust ... The problem revealed by the 2007-08 crisis was not that some financial services companies collapsed, but that there was no means of handling their failure without endangering the entire global financial system.”

Only last year Andrew Haldane, chief economist at the Bank of England, told the German magazine Der Spiegel that the balances of the big banks are “the blackest of black holes”. Haldane is responsible for the stability of the financial sector as a whole. He knowingly told a journalist that he couldn’t possibly have an idea of what the banks have on their books. And? Nothing happened.

It made sense in 2008 for those in the know not to deepen the panic by talking about it. Indeed, one of the most powerful figures in the EU in 2008, the almost supernaturally levelheaded Herman van Rompuy, waited until 2014 to acknowledge in an interview that he had seen the system come within “a few millimetres of total implosion”.

But because the general public was left in the dark, there was never enough political capital to take on the banks. Compare this to the 1930s in the US, when the crash was allowed to play out, giving Franklin D Roosevelt the chance to bring in simple and strong new laws that kept the financial sector healthy for many decades – until Reagan and Thatcher undid one part, and Clinton and Blair the other.

Tony Blair is now making a reported £2.5m a year as adviser to JP Morgan, while the former US Treasury secretary Timothy Geithner and the former secretary of state Hillary Clinton have been paid upwards of $100,000 a speech to address small audiences at global banks. It is tempting to see corruption in all this, but it seems more likely that, over the past decades, politicians as well as regulators have come to identify themselves with the financial sector they are supposed to be regulating. The term here is “cognitive capture”, a concept popularised by the economist and former Financial Times columnist Willem Buiter, who described it as over-identification between the regulator and the regulated – or “excess sensitivity of the Fed to financial market and financial sector concerns and fears”.

With corruption, you are given money to do something you would not have done otherwise. Capture is more subtle and no longer requires a transfer of funds – since the politician, academic or regulator has started to believe that the world works in the way that bankers say it does. Sadly, Willem Buiter never wrote a definitive account of capture; he no longer works in academia and journalism. He has moved to the megabank Citigroup.

The European commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, memorably said in 2013 that European politicians know very well what needs to be done to save the economy. They just don’t know how to get elected after doing it. A similar point could be made about the major parties in this country: they know very well what needs to be done to make finance safe again. They just don’t know where their campaign donations and second careers are going to come from once they have done it.

Still, the complicity of mainstream politicians is not the whole story. Finance today is global, while democratically legitimate politics operates on a national level. Banks can play off one country or block of countries against the other, threatening to pack up and leave if a piece of regulation should be introduced that doesn’t agree with them. And they do, shamelessly. “OK, let us assume our country takes on its financial sector,” a mainstream European politician told me. “In that case, our banks and financial firms simply move elsewhere, meaning we will have lost our voice in international forums. Meanwhile, globally, nothing has changed.”

This then opens up the most difficult question of all: how is the global financial sector to be brought back under control if there is no global political authority capable of challenging it?

Seven years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, it is often said that nothing was learned from the crash. This is too optimistic. The big banks have surely drawn a lesson from the crash and its aftermath: that in the end there is very little they will not get away with.

Ask people where they were on 9/11, and most have a memory to share. Ask where they were when Lehman Brothers collapsed, and many will struggle even to remember the correct year. The 158-year-old Wall Street bank filed for bankruptcy on 15 September 2008. As the news broke, insiders experienced an atmosphere of unprecedented panic. One former investment banker recalled: “I thought: so this is what the threat of war must feel like. I remember looking out of the window and seeing the buses drive by. People everywhere going through a normal working day – or so they thought. I realised: they have no idea. I called my father from the office to tell him to transfer all his savings to a safer bank. Going home that day, I was genuinely terrified.”

A veteran at a small credit rating agency who spent his whole career in the City of London told me with genuine emotion: “It was terrifying. Absolutely terrifying. We came so close to a global meltdown.” He had been on holiday in the week Lehman went bust. “I remember opening up the paper every day and going: ‘Oh my God.’ I was on my BlackBerry following events. Confusion, embarrassment, incredulity ... I went through the whole gamut of human emotions. At some point my wife threatened to throw my BlackBerry in the lake if I didn’t stop reading on my phone. I couldn’t stop.”

Other financial workers in the City, who were at their desks after Lehman defaulted, described colleagues sitting frozen before their screens, paralysed – unable to act even when there was easy money to be made. Things were looking so bad, they said, that some got on the phone to their families: “Get as much money from the ATM as you can.” “Rush to the supermarket to hoard food.” “Buy gold.” “Get everything ready to evacuate the kids to the country.” As they recalled those days, there was often a note of shame in their voices, as if they felt humiliated by the memory of their vulnerability. Even some of the most macho traders became visibly uncomfortable. One said to me in a grim voice: “That was scary, mate. I mean, not film scary. Really scary.”

I spent two years, from 2011 to 2013, interviewing about 200 bankers and financial workers as part of an investigation into banking culture in the City of London after the crash. Not everyone I spoke to had been so terrified in the days and weeks after Lehman collapsed. But the ones who had phoned their families in panic explained to me that what they were afraid of was the domino effect. The collapse of a global megabank such as Lehman could cause the financial system to come to a halt, seize up and then implode. Not only would this mean that we could no longer withdraw our money from banks, it would also mean that lines of credit would stop. As the fund manager George Cooper put it in his book The Origin of Financial Crises: “This financial crisis came perilously close to causing a systemic failure of the global financial system. Had this occurred, global trade would have ceased to function within a very short period of time.” Remember that this is the age of just-in-time inventory management, Cooper added – meaning supermarkets have very small stocks. With impeccable understatement, he said: “It is sobering to contemplate the consequences of interrupting food supplies to the world’s major cities for even a few days.”

These were the dominos threatening to fall in 2008. The next tile would be hundreds of millions of people worldwide all learning at the same time that they had lost access to their bank accounts and that supplies to their supermarkets, pharmacies and petrol stations had frozen. The TV images that have come to define this whole episode – defeated-looking Lehman employees carrying boxes of their belongings through Wall Street – have become objects of satire. As if it were only a matter of a few hundred overpaid people losing their jobs: Look at the Masters of the Universe now, brought down to our level!

In reality, those cardboard box-carrying bankers were the beginning of what could very well have been a genuine breakdown of society. Although we did not quite fall off the edge after the crash in the way some bankers were anticipating, the painful effects are still being felt in almost every sector. At this distance, however, seven years on, it’s hard to see what has changed.

A typical education in the west leaves you with more insight into ancient Rome or Egypt than into our financial system – and while there are plenty of books and DVDs for lay people about, say, quantum mechanics, evolution or the human genome, before the crash there was virtually nothing to explain finance to outsiders in accessible language. The City, as John Lanchester put it in his book about the 2008 crash, Whoops!, is still “a far-off country of which we know little”.

As a result, ordinary people trying to form an opinion about finance over the past decades have had very little to go on, and many seem to have latched on to the images provided by films and TV.

The British stereotype of the boring banker began to change in the 80s when finance was deregulated. Following Ronald Reagan’s dictum, “Government is not the solution to the problem, it is the problem”, banks were allowed to unite under one roof activities that regulation had previously required to be divided between separate firms and banks. They were able to grow to sizes many times bigger than a country’s GDP – the assumption being that the market would be self-regulating. The changes also meant that bankers became immensely powerful. Hollywood provided the City with a new hero: the financier Gordon Gekko, from Oliver Stone’s 1987 film Wall Street, who brought us the phrase “Greed is good”. In his portrait of bond traders’ raging ambition, Bonfire of the Vanities, novelist Tom Wolfe coined the term “Masters of the Universe”.

It all seemed innocent entertainment, before 2008: tales about a far-off country where boys behaved badly, scandalously even, but above all, reassuringly far away from the comfort and safety of our own homes, something like watching a Quentin Tarantino film or an episode of The Sopranos. This was the era when a Labour chancellor, Gordon Brown, could give a speech to a gathering of bankers and asset managers and tell them: “The financial services sector in Britain, and the City of London at the centre of it, is a great example of a highly skilled, high value-added, talent-driven industry that shows how we can excel in a world of global competition. Britain needs more of the vigour, ingenuity and aspiration that you already demonstrate that is the hallmark of your success.”

Those words were spoken in 2007, and a year later the world found itself in the middle of the biggest financial panic since the 1930s. In the end, it was only through a combination of pure luck, extremely expensive nationalisations and bailouts, the lowest interest rates in recorded history plus an ongoing experiment in mass money printing, that total meltdown was averted.

The post-Lehman panic was followed by a wave of investigations and reconstructions by journalists, writers and politicians. More than 300 books have been published about the crash in English alone. Every western country held extensive hearings and produced detailed recommendations. Everything you need to know about what is wrong with finance and the banks today is in their reports; the problem is that there is so much more that needs to be explained.

Most areas inside banking had little or nothing to do with the crash, while many players outside banking bore a heavy responsibility, too, including insurers, credit rating agencies, accountancy firms, financial law firms, central banks, regulators and politicians. Investors such as pension funds had been egging the banks on to make more profits by taking more risk. Unless you had a firm understanding of finance, the causes of the crash were very unclear, and this must be part of the reason why the clearest and most urgent lesson of all would get lost or buried: the financial system itself had become dangerously flawed.

After the crash of 2008, ignorance among the general public, reticence among complicit mainstream politicians and a deeply skewed and sensationalist portrayal of finance in the mass media conspired to create the narrative that the crash was caused by greed or by some other character flaw in individual bankers: psychopathy, gambling addiction or cocaine use. (A whole genre of City memoirs sprang up with titles such as Binge Trading: The Real Inside Story of Cash, Cocaine and Corruption in the City. Gordon Gekko returned for a sequel, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, and Leonardo di Caprio scored an immense hit playing the title role in The Wolf of Wall Street, about a whoring and cocaine-snorting financial fraudster.)

From there it was a small step to the notion that we can fix finance by getting rid of the “jerks”, as the plain speaking former Barclays CEO Bob Diamond put it. When Diamond was forced to resign in July 2012 over a scandal involving interest rate rigging by his traders, his successor, Antony Jenkins, also promised to focus on changing the culture. And so the same banks that brought us the mess of 2008 eagerly embraced the need for cultural change – which alone should arouse our suspicions. If there is one recurring theme in the many conversations I had with City insiders, it was the need for structural rather than cultural change; not so much different bankers, but a different system.

“Sometimes I feel as if finance has reacted to the crisis the way a motorist might after a near-accident,” said the City veteran at a small credit rating agency whose wife had almost chucked his phone into a lake at the height of the panic. “There is the adrenaline surge directly after the lucky escape, followed by the huge shock when you realise what could have happened. But as the journey continues and the scene recedes in the rear-view mirror, you tell yourself: maybe it wasn’t that bad. The memory of your panic fades, and you even begin to misremember what happened. Was it really that bad?”

He was a soft-spoken man, the sort to send a text message if he is going to be five minutes late to a meeting. But now he was really angry: “If you had told people at the height of the crisis that years later we’d have had no fundamental changes, nobody would have believed you. Such was the panic and fear. But here we are. It’s back to business as usual. We went from ‘We nearly died from this’ to ‘We survived this’.”

The City is governed by a code of silence and fear of publicity; those caught talking to the press without a PR officer present could be sacked or sued. But once I had persuaded City insiders to talk (always and only on condition of anonymity), they were remarkably forthcoming.

“I have the wrong accent and I went to a shit school,” said one City veteran, after explaining that for many years he had made millions at a top bank only to move to an even better-paying hedge fund. “Forty years ago, I wouldn’t even have been given an interview in the City. Finance today is fiercely meritocratic. Doesn’t matter if you’re gay or black or working class, if you can do something better than the other person, you’ll move up.”

He was a mathematician by training, and his direct manner reminded me of stallholders at the biggest open market in my hometown of Amsterdam – tough guys with a highly developed mistrust of pretentiousness. He fuelled himself with Diet Coke and coffee and teased me for ordering cranberry juice. Before he was recruited by the bank in the early 1990s, he had taught at a university; his only idea of an investment bank was based on two books he had read: Liar’s Poker by Michael Lewis and Barbarians at the Gate by Bryan Burrough and John Helyar. “Traders as loud, crass, bad-mouthed, macho dickheads. The sort of guys with red braces who shout ‘buy, buy, sell, sell’ into their phones and have eating competitions.” Many outsiders still believe that these are the people occupying the top positions in big banks, he said, and taking the biggest risks. “That’s over,” he told me. “Some of the best traders are now women. Totally unassuming, cerebral and talented. Trading is no longer a balls job. It’s a brains job. To be sure, the kind of maths traders now have to be able to do is not of the wildly hard variety. But it requires real skills in that area.”

He described the basic flaw in the banking system as it has evolved over the past decades: other people’s money. Until deregulation began to liberate finance from the constraints placed on it after the last major crash in the 1930s, risky banking in the City was carried out in firms that were organised as partnerships, which were not listed on the stock exchange. The partners owned and ran the firm – and when things went wrong, they were liable. Hence the system of bonuses: if you put your personal fortune on the line and things go well, it stands to reason that you deserve a big bonus. Because if things go the other way, you are personally liable for the losses.

Back in the days when his bank was still a partnership, the former banker had drawn on his gift for maths to build a complex financial product that he thought was very clever. “I was very new and maybe a bit cocky,” he said. “So I went over to the head of trading and showed it to him, saying, ‘Look, we can make a lot of money with this.’ The head of trading was a partner in the traditional sense. He looked at me and replied: ‘Don’t forget, this is my money you’re fucking with.’”

The problem with the way banks are now organised is not that they take risks – that is their job. The problem with today’s banks is that those who accept the risks are no longer those who get stuck with the bill.

A bank that is listed on the stock market loses control to the new owners; that is, the shareholders. When these shareholders, which can include insurers, wealthy dynasties or pension funds, start demanding ever greater profits, then greater profits are what you have to deliver. In 2007, in an inadvertent moment of candour, the then CEO of the megabank Citigroup, Charles O Prince, summarised this relationship: “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.”

This dynamic became all the more dangerous as globalisation began to create a single market for finance. Not only were partnerships allowed to be listed on the stock exchange or taken over by a publicly listed bank, they were also allowed to go on a global shopping spree. Wave after wave of mergers and acquisitions meant banks could generate higher profits than the GDPs of their host countries, resulting in the institutions that we now know as “too big to fail” – so big that if they go bust, they can bring down the system with them. When excessive risk turns sour, it’s the taxpayer who suffers.

In a functioning free market system, incompetence and recklessness are punished by failure and bankruptcy. But there is currently no functioning free market at the centre of the global free market system. I heard City workers scoff at the employees of banks that cannot be allowed to fail – calling them overpaid civil servants who play a game they cannot lose. Risk-taking at a bank that will always be saved, they said, is like playing Russian roulette with someone else’s head.

In the old days, veterans told me, there was an office party almost every Friday: celebrating the anniversary of someone who had stayed with the firm for 20 years or longer. That is all over now, and in its place has come a hire-and-fire culture characterised by an absence of loyalty on either side. Employment in the City is now a purely transactional affair. It is exceedingly rare to find people who have stayed with the same bank for their entire career.

Many of the insiders I spoke to had stories about abrupt sackings: You get a call from a colleague, saying: “Look, could you do me a favour and get my coat and bag?” She is standing outside with a blocked security pass. One morning, you swipe your pass only to hear a beep and find your entrance barred. You turn to the receptionist who says, after a glance at her computer screen, “Would you please have a seat over there until somebody comes to fetch you?”

In the City, sudden dismissals of this kind have a name: “executions”. Add to these the quarterly “waves” when headquarters decides to reduce headcount and a certain percentage of staff worldwide are given the sack, all on one day. Some banks operate a “cull”. Every year, prestigious banks such as Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan routinely fire their least profitable staff. “When the cull comes ...” people would say, or: “Oh yes, we cull.”

“When you can be out of the door in five minutes, your horizon becomes five minutes,” one City worker told me. Another asked: “Why would I treat my bank any better than my bank treats me?”

If the threat of being culled influenced bankers’ behaviour through fear, there were also powerful motivations. Deregulation has allowed perverse incentives into the very fabric of global finance. People are faced with immense temptations to take risks with their bank’s capital or reputation, knowing that if they don’t act on them, their colleague across the desk will.

Before the deregulation of the 80s and 90s, the City was far from perfect: it was a snobbish, antisemitic and misogynistic place. But the City – and Wall Street – of old was a world that Gus Levy, head of Goldman Sachs in the 70s, famously described as “long term greedy”; you made money with your client and your firm. Because partners were personally liable, they had an interest in keeping their firm on a manageable scale and making sure their employees told them of any risks. In a few decades, this system has evolved into one that Levy called “short term greedy”; you make money at the expense of the client, of the bank, of the shareholder or of the taxpayer. This did not happen because bankers suddenly became evil, but because the incentives fundamentally changed.

Until the mid 80s, the London Stock Exchange’s motto was dictum meum pactum, “my word is my bond”. These days the governing principle is caveat emptor, or “buyer beware” – it is effectively up to the professional investor to figure out what the bank is offering. As one builder of complex financial products explained to me: “You have got to read the small print. You need to bring in a lawyer who explains it to you before you buy these things.”

Perhaps the most terrifying interview of all the 200 I recorded was with a senior regulator. It was not only what he said but how he said it: as if the status quo was simply unassailable. Ultimately, he explained, regulators – the government agencies that ensure the financial sector is safe and compliant – rely on self-declaration; what is presented by a bank’s internal management. The trouble, he said with a calm smile, is that a bank’s internal management often doesn’t know what’s going on because banks today are so vast and complex. He did not think he had ever been deliberately lied to, although he acknowledged that, obviously, he couldn’t know for sure. “The real threat is not a bank’s management hiding things from us, it’s the management not knowing themselves what the risks are.”

He talked about the culture of fear and how people are not managing their actions for the benefit of their bank. Instead, “they are managing their career”. He believed that the crash had been more “cock-up than conspiracy”. Bank management is in conflict, he pointed out: “What is good for the long term of the bank or the country may not be what is best for their own short-term career or bonus.”

If the problem with finance is perverse incentives, then the insistence on greed as the cause for the crash is part of the problem. There is a lot of greed in the City, as there is elsewhere in society. But if you blame the crash on character flaws in individuals you imply that the system itself is fine, all we need to do is to smoke out the crooks, the gambling addicts, the coke-snorters, the sexists, the psychopaths. Human beings always have at least some scope for choice, hence the differences in culture between banks. Still, human behaviour is largely determined by incentives, and in the current set-up, these are sending individual bankers, desks or divisions within banks – as well as the banks themselves – in the wrong direction.

How hard would it be to change those incentives? From the viewpoint of those I interviewed, not hard at all. First of all, banks could be chopped up into units that can safely go bust – meaning they could never blackmail us again. Banks should not have multiple activities going on under one roof with inherent conflicts of interest. Banks should not be allowed to build, sell or own overly complex financial products – clients should be able to comprehend what they buy and investors understand the balance sheet. Finally, the penalty should land on the same head as the bonus, meaning nobody should have more reason to lie awake at night worrying over the risks to the bank’s capital or reputation than the bankers themselves. You might expect all major political parties to have come out by now with their vision of a stable and productive financial sector. But this is not what has happened.

Not that there has been no reform. Banks are taxed when they get beyond a certain size, for example, and all banks must now finance a larger part of their risks with equity rather than borrowed money. American banks are banned from using their own capital to speculate and invest in the markets, and the European commission, or national governments, have forced a few banks to shrink or sell off their investment bank activities – the Dutch bank ING, for example, was told to sell off its insurance arm, ING Direct. But change has been largely cosmetic, leaving the sector’s basic architecture intact. If a bank collapses, the new European banking union – set up in 2012 to transfer banking policy from a national to a European level – is meant to step in and wind it down in an orderly fashion. But who is propping up that European banking union, if several banks should fail at the same time? The taxpayer. A bonus cap in banking was introduced by the EU, so instead of paying widely publicised million-pound bonuses, banks now simply offer higher salaries.

Perhaps the most promising change in the UK is the so-called “senior person regime” that makes it possible to prosecute bankers for reckless behaviour – but only after they have wrecked their bank. Virtually all big banks remain publicly listed or are doing everything they can to get back on the stock exchange. They have never allowed staff to talk openly about what went wrong before 2008 and why. The code of silence remains intact. The banks have not sacked the accountancy firms or credit rating agencies that failed to raise the alarm over the erroneous or misleading items on their balance sheets. Banks have certainly not joined hands to fight for a globally enforced increase in capital buffers (the minimum capital they are required to hold), which could help them absorb and survive severe losses. Indeed, they have spent millions lobbying to keep any increase in buffers as low as possible.

“Back to business as usual.” This is how many interviewees described the post-crash atmosphere in the City. As the senior regulator put it with chilling equanimity: “Is the sector fixed, after the crisis? I don’t think so.” What we have now, he added, is “what you get with free-market capitalism – consolidation of all wealth into fewer and fewer banks, which end up dividing up the market as a cartel.”

When it comes to global finance, the most startling news isn’t news at all; the important facts have been known for a long time among insiders. The problem goes much deeper: the sector has become immune to exposure.

“If I had a million pounds for every time I have heard a possible reform opposed because ‘it wouldn’t have prevented Northern Rock or Lehman Brothers going bust’, I might now have enough money to bail out a bank,” the Financial Times columnist John Kay wrote in 2013. “The objective of reform is not to prevent Northern Rock or Lehman going bust ... The problem revealed by the 2007-08 crisis was not that some financial services companies collapsed, but that there was no means of handling their failure without endangering the entire global financial system.”

Only last year Andrew Haldane, chief economist at the Bank of England, told the German magazine Der Spiegel that the balances of the big banks are “the blackest of black holes”. Haldane is responsible for the stability of the financial sector as a whole. He knowingly told a journalist that he couldn’t possibly have an idea of what the banks have on their books. And? Nothing happened.

It made sense in 2008 for those in the know not to deepen the panic by talking about it. Indeed, one of the most powerful figures in the EU in 2008, the almost supernaturally levelheaded Herman van Rompuy, waited until 2014 to acknowledge in an interview that he had seen the system come within “a few millimetres of total implosion”.

But because the general public was left in the dark, there was never enough political capital to take on the banks. Compare this to the 1930s in the US, when the crash was allowed to play out, giving Franklin D Roosevelt the chance to bring in simple and strong new laws that kept the financial sector healthy for many decades – until Reagan and Thatcher undid one part, and Clinton and Blair the other.

Tony Blair is now making a reported £2.5m a year as adviser to JP Morgan, while the former US Treasury secretary Timothy Geithner and the former secretary of state Hillary Clinton have been paid upwards of $100,000 a speech to address small audiences at global banks. It is tempting to see corruption in all this, but it seems more likely that, over the past decades, politicians as well as regulators have come to identify themselves with the financial sector they are supposed to be regulating. The term here is “cognitive capture”, a concept popularised by the economist and former Financial Times columnist Willem Buiter, who described it as over-identification between the regulator and the regulated – or “excess sensitivity of the Fed to financial market and financial sector concerns and fears”.

With corruption, you are given money to do something you would not have done otherwise. Capture is more subtle and no longer requires a transfer of funds – since the politician, academic or regulator has started to believe that the world works in the way that bankers say it does. Sadly, Willem Buiter never wrote a definitive account of capture; he no longer works in academia and journalism. He has moved to the megabank Citigroup.

The European commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, memorably said in 2013 that European politicians know very well what needs to be done to save the economy. They just don’t know how to get elected after doing it. A similar point could be made about the major parties in this country: they know very well what needs to be done to make finance safe again. They just don’t know where their campaign donations and second careers are going to come from once they have done it.

Still, the complicity of mainstream politicians is not the whole story. Finance today is global, while democratically legitimate politics operates on a national level. Banks can play off one country or block of countries against the other, threatening to pack up and leave if a piece of regulation should be introduced that doesn’t agree with them. And they do, shamelessly. “OK, let us assume our country takes on its financial sector,” a mainstream European politician told me. “In that case, our banks and financial firms simply move elsewhere, meaning we will have lost our voice in international forums. Meanwhile, globally, nothing has changed.”

This then opens up the most difficult question of all: how is the global financial sector to be brought back under control if there is no global political authority capable of challenging it?

Seven years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, it is often said that nothing was learned from the crash. This is too optimistic. The big banks have surely drawn a lesson from the crash and its aftermath: that in the end there is very little they will not get away with.

Tuesday, 2 December 2014

Why doctors fail

Atul Gawande in the Guardian

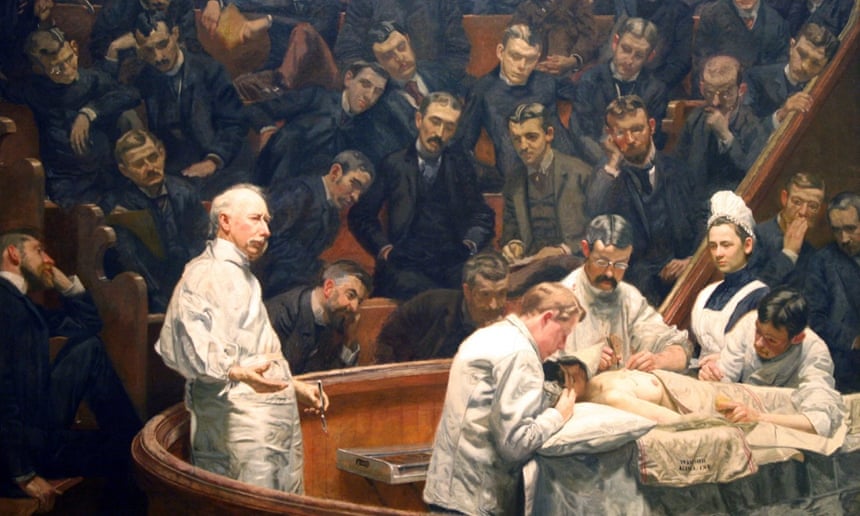

Doctors are fallible; of course they are. So why do they find this so hard to admit, and how can they work more openly? Atul Gawande lifts the veil of secrecy in the first of his Reith lectures

Millions of moments like this occur every day: a human being coming to another human being with the body or mind’s troubles and looking for assistance. That is the central act of medicine – that moment when one human being turns to another human being for help.

And it has always struck me how small and limited that moment is. We have 13 different organ systems and at the latest count we’ve identified more than 60,000 ways that they can go awry. The body is scarily intricate, unfathomable, hard to read. We are these hidden beings inside this fleshy sack of skin and we’ve spent thousands of years trying to understand what’s going on inside. To me, the story of medicine is the story of how we deal with the incompleteness of our knowledge and the fallibility of our skills.

There was an essay that I read two decades ago that I think has influenced almost every bit of writing and research I’ve done ever since. It was by two philosophers – Samuel Gorovitz and Alasdair MacIntyre – and their subject was the nature of human fallibility. They wondered why human beings fail at anything that we set out to do. Why, for example, would a meteorologist fail to correctly predict where a hurricane was going to make landfall, or why might a doctor fail to figure out what was going on inside my son and fix it? They argued that there are two primary reasons why we might fail. The first is ignorance: we have only a limited understanding of all of the relevant physical laws and conditions that apply to any given problem or circumstance. The second reason, however, they called “ineptitude”, meaning that the knowledge exists but an individual or a group of individuals fail to apply that knowledge correctly.

We’ve relied on science to overcome ignorance, and the course of that work has itself been fascinating. That visit we made in 1995 to our paediatrician and everything that she did to sort out what was happening in my son could be traced back to 1628 when the English physician William Harvey, after millennia of ignorance, finally worked out that the heart is a pump that moves blood in a circular course through the body.

Another critical step came three centuries later, in 1929, when Werner Forssmann, a surgical intern in Eberswalde, Germany, made an observation. Forssmann was reading an obscure medical journal when he noticed an article depicting a horse in which researchers had threaded a long tube up its leg all the way into its heart. They described, to his amazement, taking blood samples from inside a living heart without harm. And he said: “Well, if we could do that to a horse, what if we did that to a human being?” Forssmann went to his superiors and said: “How about we take a tube and thread it into a human being’s heart?”

Their response was, in essence, “You’re crazy. You can’t do that. Whenever anyone touches the heart in surgery, it goes into fibrillation and the patient dies.”

He said: “Well what about in an animal?”

And they said: “There’s no point and you’re just an intern anyway. Who says you should even deserve to get to ask these questions? Go back to work.”

But Forssmann just had to give it a try. So he stole into the x-ray room, took a urinary catheter, made a slit in his own arm, threaded it up his vein and into his own heart and convinced a nurse to help him take a series of nine x-rays showing the tube inside his own heart.

He published the evidence – and was fired. Then in 1956, he was awarded the Nobel prize in medicine with André Cournand and Dickinson Richards who, some 20 years later at Columbia University, had taken Forssmann’s findings and recognised that you could not only put a catheter into the human heart but also shoot dye through the catheter. That enabled them to take pictures and see from the inside how the heart actually worked. Together the three had founded the field of cardiology. After this, doctors began devising ways to fix what was found going wrong inside the heart.

Science is concerned with universal truths, laws of how the body or the world behaves. Application, however, is concerned with the particularities, and the test of the science is how the universalities apply to the particularities. Do the general ideas about the worrying sounds the paediatrician heard in my son’s chest correspond with the unique particularities of Walker? Here Gorovitz and MacIntyre saw a third possible kind of failure. Besides ignorance, besides ineptitude, they said that there is necessary fallibility, some knowledge science can never deliver on. They went back to the example of how a given hurricane will behave when it makes landfall, how fast it will be going when it does, and what they said is that we’re asking science to do more than it can when we ask it to tell us what exactly is going on. All hurricanes follow predictable laws of behaviour but no hurricane is like any other hurricane. Each one is unique. We cannot have perfect knowledge of a hurricane, short of having a complete understanding of all the laws that describe natural processes and a complete description of the world, they said. It required, in other words, omniscience, and we can’t have that.

The interesting question, then, is how do we cope? It’s not that it’s impossible to predict anything. Some things are completely predictable. Gorovitz and MacIntyre gave the example of a random ice cube in a fire. An ice cube is so simple and so similar to other ice cubes that you can have complete assurance that if you put it in the fire, it will melt. Our puzzle is: are human beings more like hurricanes or more like ice cubes?

Following the paediatrician’s instructions, we took Walker to the emergency room. It was a Sunday morning. A nurse took an oxygen monitor, one of those finger probes with the red light, and put it on the finger of his right hand. And the oxygen level was 98%, virtually perfect. They took a chest x-ray, and it showed that the lungs were both whited out. They read it. They said: “This is pneumonia.” They did a spinal tap to make sure that it wasn’t signs of infection that had spread from meningitis. They started him on antibiotics and they called the paediatrician to let her know the diagnosis they’d found. It wasn’t the heart, they said. It was the lungs. He had pneumonia. And she said: “No, that can’t be right.” She came into the emergency room and she took one look at him – he was having trouble breathing, he was not doing great – and she saw that the finger probe with the oxygen monitor was on the wrong finger.

It turns out there are certain conditions in which the aorta can be interrupted. You can be born with an incomplete aorta and so the blood flow can come out of the heart and go to the right side of the upper body, into the hand that had that probe, but it may not go to the left side of the upper body or anywhere else. And that turned out to be what was going on. She switched the probe over to the left hand and he had an unreadable oxygen level. He was in fact going into kidney and liver failure. He was in serious trouble. She had caught a failure to apply the knowledge science has to this particular situation.

Then the team made a prediction. In this circumstance, we do have a drug – only put into use, it turned out, about a decade before my son was born: prostaglandin E2, a little molecule that can reopen the foetal circulation. When you’re a foetus in the womb, you have a bypass system that sends a separate blood supply that can stay open for a couple of weeks after birth. This system had shut down and that’s why he went into failure. But this molecule can reopen that pathway and the prediction was that this child was like every other child – that you could know what had happened to other children and could apply it here and that it would open up that foetal circulation, this bypass system. And it did. That gave him time to recover in the intensive care unit, to let his kidney and his liver recover, to let his gut start working again, and then to undergo cardiac surgery to replace his malformed aorta and to fix the holes that were present in his heart as well. They saved him.

They saved him.

There are more and more ways in which we are as knowable as ice cubes. We understand with great precision how mothers can die in childbirth, how certain tumours behave, how the Ebola virus spreads, how the heart can go wrong and be fixed. Certainly, we have many, many areas of continuing ignorance – how to stop Alzheimer’s disease or metastatic cancers, how we might make a vaccine against this virus we’re dealing with now. But the story of our time, I think, is as much a story about struggling with ineptitude as struggling with ignorance.

You go back a hundred years or more, and we lived in a world where our futures were governed largely by ignorance. But over this last century, we’ve come through an extraordinary explosion of discovery. The puzzle has, therefore, become not only how we close the gaps of ignorance open to us, but also how we ensure that the knowledge gets through, that the finger probe is on the correct finger.

Next to my son, in the intensive care unit, there was a child from Maine, which is about 200 miles away, who had virtually the same diagnosis that Walker had. And when this boy was diagnosed, it took too long for the problem to be recognised, for transportation to be arranged, and for him to get that drug to give him back that open circulation. The result was that the poor child with the same condition my son had, in the very next bed to ours, gone into complete liver and kidney failure, and his only chance was to wait for an organ transplant and hope for a future that was going to be very different from the one my son was going to have.

And then I think back on my family. My parents come from India; my father from a rural village, my mother from a big city in the north. If Walker had been anything like my nieces and nephews in the village where my family still farms – they’re farmers growing wheat and sugarcane and cotton – and if he’d been there, there would have been no chance at all.

There’s a misconception about global health. We think global health is about care in just the poorest parts of the world. But the way I think about global health, it’s about making care better everywhere – the idea that we are trying to deploy the capabilities that we have discovered over the last century, town by town, to every person alive. We’ve had an extraordinary transformation around the world. Economically, even with the last recession, we’ve had the rising of global economies on every continent and the result has been a dramatic change in the length of lives all across the world. Respiratory illness and malnutrition used to be the biggest killers. Now it’s cardiovascular disease; road traffic accidents are a top five killer and cancers are in the top 10. With economic progress has come the broader knowledge for people that solutions exist.

My family members in our village in India know that solutions exist to the problems they have, and so the puzzle is how we deploy that capability everywhere – in India, in Maine, across the UK, Europe, Latin America, the world. We’re only just discovering the patterns of how we begin to do that.

In the course of this year’s Reith lectures, I’m going to attempt to unpack three ideas. First is what we’re learning from opening the door, from seeing behind the curtains of how medicine and public health are actually practised and discovering how much can be done better that saves lives and reduces suffering. Second is the reality of our necessary fallibility and how we cope effectively with the fact that our knowledge is always limited. Third, I will consider the implications of both of these – the implications of what we’re learning about our ineptitude and about our necessary fallibility – for the global future of medicine and health.

It is uncomfortable looking inside our fallibility. We have a fear of looking. We’re like the doctors who dug up bodies in the 19th century to dissect them, in order to know what was really happening inside. We’re looking inside our systems and how they really work. And like before, what we find is messier than we knew and sometimes messier than we might have wanted to know.

In some ways, turning on the cameras inside our world can be more treacherous. There’s a reason that Gorovitz and MacIntyre labelled the kind of failures we have “ineptitude”. There’s a sense that there’s some shame or guilt attached to the fact that we don’t get it right all the time. And exposing this reality can make people more angry than exposing the reality of how the body works. Therefore, we’ve blocked many of these efforts to try to provide some transparency to what’s going on. Audiotapes are often not allowed, the video recorders are turned off. We have no black box for what happens in our operating rooms or in our clinics. The data, when we have it, is often locked up. You can’t know, even though we have the information, which hospitals have a better complication rate in certain kinds of operations than others. There’s a fear of misuse, a fear of injustice in doing it, in exposing it.

Arguably, not opening up the doors puts lives at stake. What we find out can often be miraculous. By closing ourselves off, we’re missing important opportunities.

The doctors told us when Walker went home that he was going to need a second operation. The repair that he’d had was one that replaced a section of his aorta – the tube coming out of his heart to carry blood supply throughout the rest of the body – with an artificial tube when he was 11 days old. It was almost like a straw. Now they had designed it to expand a bit as he grew, but it was not going to accommodate an adult-sized body. So they told us that when he became a teenager he would have to get a new replacement aorta and that he would have to undergo a major operation. Being a surgery resident, I knew what that entailed. Repeat aortic surgery has up to a 5% chance of death and a 25% chance of paralysis. We lived in some fear about when that moment would come.

When that moment came, he was 14 years old, and the world had changed. By then technology had developed to allow his aorta to be expanded with a simple catheter. We found the expert who had learned, and even devised, some of the methods for being able to do that, in Boston. He explained to me, cardiologist to surgeon, just how it’s done and sometimes you learn stuff you don’t necessarily want to know. He talked about how he would have to apply pressure to a balloon that would be threaded up inside the aorta. I asked how he knew what pressure to apply. He said it was by feel. He could feel the vessel tearing, and the trick was to tear it just enough that it can expand but not so much that it ruptures.

There was a necessary fallibility in what he was attempting to do – some irreducible probability of failure. But Walker got through that procedure just fine. The extraordinary thing was the very next day he went home, and the day after that he was so well that he played sports and injured his ankle on the playing field. This June he graduated from high school and this autumn he started college. He’s going to live a long and normal life, and that is amazing. The key question we have to ask ourselves is how are we going to make it possible for others to have that, how do we fulfil our duty to make it possible for others? The only way I can see is by removing the veil around what happens in that procedure room, in that clinic, in that office or that hospital. Only by making what has been invisible visible. This is why I write, this is why we do the science we do – because this is how we understand – and that is the key to the future of medicine.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)